Abstract

The evolution of monogamy and paternal care in humans is often argued to have resulted from the needs of our expensive offspring. Recent research challenges this claim, however, contending that promiscuous male competitors and the risk of cuckoldry limit the scope for the evolution of male investment. So how did monogamy first evolve? Links between mating strategies and partner availability may offer resolution. While studies of sex roles commonly assume that optimal mating rates for males are higher, fitness payoffs to monogamy and the maintenance of a single partner can be greater when partners are rare. Thus, partner availability is increasingly recognized as a key variable structuring mating behavior. To apply these recent insights to human evolution, we model three male strategies – multiple mating, mate guarding and paternal care – in response to partner availability. Under assumed ancestral human conditions, we find that male mate guarding, rather than paternal care, drives the evolution of monogamy, as it secures a partner and ensures paternity certainty in the face of more promiscuous competitors. Accordingly, we argue that while paternal investment may be common across human societies, current patterns should not be confused with the reason pairing first evolved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The evolution of monogamy in humans is commonly argued to have been driven by the need for paternal investment (reviewed in ref. 1). Specifically, the unique suite of human life history traits - altricial young, a long juvenile period, delayed maturity, extension of the lifespan and large brains - are often claimed to have resulted from the emergence of male care2. While these claims are contentious for various reasons3,4, ultimately they ignore the social dilemma males face regarding shifting reproductive strategies5. The switch from a mating effort intensive strategy (i.e., multiple mate appropriation) to a paternal investment strategy (i.e., resource production) is prone to free-riding by male competitors, raising questions about a straightforward promiscuity-to-monogamy mating system transition in human evolution1,6. A commonly ignored pathway, which may provide some degree of resolution to this puzzle, is through frequency dependent payoffs to mate guarding7,8. Male mate guarding is present across animal taxa and is often expressed as monogamy without paternal care9.

Why do men care?

Human offspring are born highly vulnerable and slow-maturing and generally receive investment from both parents2,10. However, biparental care is unusual across mammals11, likely because it does not result from a simple cooperative system of joint investment by males and females. While each investment in an offspring provides benefits to the parent, it also benefits his/her partner, creating conflict between parents over who pays the ‘costs’ of care (e.g., reduced mating opportunities12,13,14,15). The dominance of maternal only care in mammals is typically linked to sex differences in relative parental investment12. It is argued that because males invest less initially, due to anisogamy, they have a higher potential reproductive rate and benefit more from mating multiply than do females16. Consequently, selection favored heavy investment in parental care in females and mate seeking and competitive behaviors in males. Therefore, higher optimal mating rates for males render monogamy and care by men an evolutionary puzzle.

Long-standing claims in the literature argue that during human evolution the increased need for paternal investment created selective pressure for long-term pair bonds and a sexual division of labor17,18. However, growing evidence suggests that paternal care evolves only after monogamy becomes established in a population19. Because male investment likely would have resulted in male absence (e.g., through resource provisioning), caring males would have faced potential fitness costs due to freerider males that ‘steal’ paternity5,6. Specifically, males that do not care benefit directly from cuckolded caring males’ investments in offspring that are not theirs. As a consequence, assumptions of paternal care driving monogamy are likely overly simplistic9,20. For example, a recent survey found that over 40% of socially monogamous species exhibit no indication of male care21. Accordingly, while paternal investment may be common across human societies, current patterns should not be confused with the reason that pairing evolved in the first place. Consequently, the question becomes, why did men originally pairbond?

Why do men pairbond?

Two common alternative arguments for the evolution of monogamy exist in the literature. The first argument suggests that monogamy evolved due to selective pressure favoring males that protected their offspring from attacks by infanticidal competitors22,23. However, recent phylogenetic analyses cast doubt on this claim and find that across animal taxa the evolution of monogamy is unassociated with the risk of infanticide21. The second argument focuses on patterns of female distribution24. Solitary females spread across a landscape, due to resource dispersal and/or female intolerance, limit multiple mate monopolization opportunities for males and favor monogamy as a consequence21,25,26. While this argument may hold for many mammals, this explanation is incongruous for many group-living species, including humans and other primates27.

A growing body of theoretical and empirical research highlights another pathway to monogamy, and a possible crucial step in the evolution of paternal care, through male mate guarding (defined as the close association between a male and female prior to and/or after copulation for paternity assurance19). While research on the evolution of reproductive strategies in humans often reports that the optimal male mating strategy is the pursuit of multiple partners, these modeling approaches typically assign fitness payoffs based on the effort males devote to a particular strategy rather than on the availability of partners5,6. Consequently, there may be overlooked conditions under which, instead of mating multiply, it may be in the best interest of a male to achieve high paternity with a single female28. This trade-off is particularly acute in response to partner availability. When the mating pool is male-biased, males face difficulty in finding additional mates and a current partner becomes a valued resource, favoring mate guarding8,9,29. Accordingly, the adult sex ratio (number of sexually mature males to females in a population; ASR) becomes a key determinant to fitness payoffs of a particular male strategy7.

Following recent theoretical and empirical findings, we seek to examine a largely overlooked and possible intermediate step in the evolution of humans from an ancestral multi-male/female mating system with promiscuous mating1 to monogamy and paternal care: male mate guarding in response to partner scarcity. We model the response of three male strategies – multiple mate seeking, mate guarding, and paternal care – to fluctuating paternity certainty, benefits to paternal care, and partner availability. In doing so, we seek to offer insight and evaluate key claims for the emergence of monogamy and paternal care in humans.

Model Specification

Verbal description of the model

We investigate the selective advantage of three male strategies: Multiple Mating (MM), Mate Guarding (MG), and Paternal Care (PC). Male reproductive success depends on the ratio of available males to females at a particular time and the frequency of the three male strategies. In the model, all males stay in the mating pool during their lifetime except for MG males who leave the mating pool with an encountered female. The probability that a male mates with a female at a particular time is dependent on the ASR, upper-bounded by 1 (i.e., all males will mate when females are in excess), with some variation across the three male strategies.

PC males provide a survival benefit ( c ) to offspring through provisioning. They pair with a female but do not mate guard, therefore there is a probability of cuckoldry ( k ). MM males will attempt to mate with multiple females, with reproductive benefits reflecting shared paternity across available females. If there are PC males in the population, MM males may gain additional reproductive benefits through cuckoldry. MG males, if they meet a female, will guard their partner to prevent cuckoldry, forgoing other mating opportunities9,30, and mate with the same female during their lifetime, which is determined by the probability of male survival (u).

These dynamics are represented in schematic form in Fig. 1. In step 1, males encounter females randomly, irrespective of their strategy, where the probability of a male encountering a female is solely dependent on the ASR. After an encounter, PC and MG males form pairbonds with females. MM males share paternity across females not paired with MG males and may additionally mate with females paired with PC males, who are at risk to cuckoldry. This risk is determined by three key factors: 1) the willingness of females to engage in extra-pair mating, 2) the possibility that females have not yet become pregnant by a PC male, which is determined by a conception rate parameter in the model ( b ; set to 0.3 following data on monthly conception rates among women without fertility problems31) and 3) the frequency of MM males (i.e., if they are rare the probability that they encounter a female paired with a PC male is low). Moving to step 2, MG males paired in step 1 have effectively removed their partners from the mating pool, thereby reducing the number of available females, and the process begins again. Over multiple steps the summed fitness benefit for each strategy reaches an asymptote, which informs the evolutionary dynamics of the three male strategies.

Squares encompass females paired with either Mate Guarding (MG) or Parental Care (PC) males, with MG-paired females leaving the mating pool each time step. Females not in squares have paternity shared among Multiple Mating (MM) males. The dotted arrow represents some paternity given to MM males through cuckoldry.

Results

We begin by presenting the evolutionary outcomes due to selection of the three male strategies in response to a mammalian typical female-biased ASR and adult survival probability (u = 0.9; see ref. 32), as well as human conception rates ( b = 0.3; Fig. 2). With weak and moderate benefits to care, a 1% and 50% increase in offspring survival respectively, we find that MM males are strongly favored regardless of paternity certainty (Fig. 2a,b,d,e). However, when we maximize benefits to care, the level of cuckoldry plays an important role (Fig. 2c,f). Doubling the benefits to care ( c = 1) and ensuring paternity certainty yields a mixed strategy equilibrium of PC and MM males (Fig. 2c). Low paternity certainty, however, returns our previous findings favoring MM males (Fig. 2f). In sum, under most conditions, males that pairbond have depressed genetic fitness outcomes relative to MM males due to their restricted sexual strategy in the face of partner abundance. However, if we assume female faithfulness to a heavily investing male6, PC males are expected to be as abundant as MM males (Fig. 2c).

The panels present six conditions with varying cuckoldry risk and payoffs to parental care (a–f) where conception rate (b) is set to 0.3. Colors denote which strategy is favored at a given strategy frequency, with yellow indicating Mate Guarding (MG), red Multiple Mating (MM), and blue Paternal Care (PC). Arrows simulate evolutionary trajectories at contrasting mixed-strategy frequencies. Color combination purple indicates when both MM and PC strategies are simultaneously increasing in frequency.

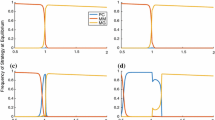

Next, we move to a male-biased ASR to examine the relative payoffs of the three strategies in response to partner scarcity (Fig. 3). Here, with weak and moderate benefits to care, and regardless of cuckoldry level, we find that MG males are most successful (Fig. 3a,b,d,e). However, as shown above, we again see variation emerge in the optimal male strategy when we double the benefits to care. Instead of a mixed-strategy, as in the female-biased condition, we find that both MG and PC males represent evolutionary stable strategies when paternity certainty is high (Fig. 3c). However, the domain of attraction for PC males decreases with lower paternity certainty, though a mixed strategy between MM and PC males will remain unless a certain threshold of MG males are present (Fig. 3f; see SI Fig. 2 for the role of conception rates that are lower and higher than 0.3 on male strategies). In sum, with low and moderate benefits to care, MG males perform best. However, with maximal benefits to care and no cuckoldry, the PC and MG strategies become competing equilibria33.

The panels present six conditions with varying cuckoldry risk and payoffs to parental care (a–f) where conception rate (b) is set to 0.3. Colors denote which strategy is favored at a given strategy frequency, with yellow indicating Mate Guarding (MG), red Multiple Mating (MM), and blue Paternal Care (PC). Arrows simulate evolutionary trajectories at contrasting mixed-strategy frequencies. Color combination yellow-blue indicates when both MG and PC strategies are simultaneously increasing in frequency.

Lastly, we evaluate male fitness outcomes across a range of ASR values (Fig. 4). In particular, we seek to present the relative payoffs for the three strategies when the ASR is at or near parity (1 male for every 1 female) and MM males are initially common (following the typically assumed ancestral condition), while adjusting the benefits to care (c) and rate of cuckoldry (k). When returns to caring are low and cuckoldry common (Fig. 4a), we find that MM is the favored strategy at female-biased ASRs. However, moving right along the x-axis, as the ASR approaches parity, and continues to becomes increasingly male-biased, we see a mixed ESS of MM and MG males, with the equilibrium frequency of MG males increasing until it becomes the (pure) ESS at an ASR of ~1.1 (i.e., 110 males for every 100 females). The story is very similar if we keep payoffs to care low, but remove the risk of cuckoldry (Fig. 4c). While we find some increase in the frequency of PC males when MG males become more common, MG males become the favored strategy more quickly under these conditions. However, when we maximize payoffs to care, we find a mixed equilibrium between PC and MM males across a wider range of ASR values (Fig. 4b). Nonetheless, in male-biased populations (~1.3+), MG males again become most common. This scope for MG males disappears however when we remove cuckoldry risk (Fig. 4d). In sum, we show that under conservative conditions (low benefits to care and high rates of cuckoldry), MG males perform best across male-biased sex ratios. However, under opposite conditions (high benefits to care and low rates of cuckoldry) PC male perform best under a wide range of ASR values (please visit the link https://abell.shinyapps.io/SexRatioSimulation/ to construct your own version of the model to see how varying parameters beyond what we present here affect the relative frequencies of the three strategies and see the Supplementary Information for the R code used to build our models).

Discussion

Here we are interested in exploring possible pathways for the evolution of monogamy and paternal care in our lineage. To make this question tractable, we allow males to engage in one of three strategies. This is a limitation of our modeling approach, however, with a polymorphic model specification, we can interpret the evolutionary dynamics more clearly in terms of the characteristics of each strategy. Accordingly, we show that when partners are abundant, multiple mating, and not pairbonded, males generally see the greatest fitness returns to their strategy. On the other hand, when males are abundant and partners are rare, males that pairbond generally do best. While we do find scope for the evolution of care in our models, the parameter estimates require paternal care to increase offspring survival considerably in the presence of limited cuckoldry (Figs 2c and 3c). Therefore we believe our findings support previous work that challenges straightforward arguments of a promiscuity to paternal care transition in human evolution. Instead, we offer mate guarding as a possible pathway to elevate paternity certainty and allow for monogamy to evolve in humans. Once pairbonding becomes established, this then allows selection to operate on variation in the amount of care provided by males.

Below we discuss the applications of our findings to: (i) current criticisms of the classical model of sexual selection, (ii) recent research on frequency dependent reproductive decision making, (iii) the evolution of human life history and its sex ratio consequences, and (iv) interpretations for the evolution of paternal care in humans.

Classical sexual selection theory predicts that the relative parental investment of the sexes leads to sex differences in optimal mating rates12,16,34. It is argued that because males invest less in any one reproductive event, as a consequence of anisogamy, they benefit more from mating multiply than do females. Moreover, a persistent theme in the literature is the claim that a shortage of females results in elevated mating effort among males34. However, our results do not support claims that male benefits to mating multiply are always high and highlight the importance of frequency dependent dynamics patterning reproductive behavior. We show that it is often in the best interest of a male to forgo pursuing multiple mating opportunities and instead achieve high paternity certainty with a single partner.

These results are in line with a growing body of theoretical and empirical work in the biological and social sciences showing reproductive decisions in response to partner availability that counter conventional assumptions7,36. For example, among humans, an abundance of men is associated with higher rates of relationship commitment35, monogamy38,39, lower reproductive skew among males40, and less promiscuity in both sexes40,42. These findings are consistent with a recent analysis of 187 bird species41 and other studies across diverse animal taxa showing that male-biased sex ratios are consistently associated with higher rates of pairbonding44,45,46,47,48. Thus, a growing body of literature highlights that partner rarity intensifies male commitment to pairbonded strategies, rather than multiple mate-seeking, across populations of both human and nonhuman animals.

When modeling the evolution of monogamy, we begin by assuming a typical mammalian female-biased ASR49. In line with patterns of mammalian mating, we find that across most conditions the optimal strategy for males is to pursue multiple mates. Males that attempt to pairbond do not take advantage of the relative female abundance and as a consequence cannot compete with MM males. However, when we examine male strategies in response to a male-biased ASR, monogamous males perform best. Our findings support empirical research, primarily among birds, showing that where male-biased sex ratios dominate, monogamy is most common43,50. The relevance of these typically bird-like male-biased sex ratios to human evolution is currently an open question. However, while our closest relatives have typical mammalian female-biased sex ratios51, human sex ratios are considerably more male-biased8,36,52 and bird-like49,53. Thus the question becomes, did our ancestors experience a change in the direction of the sex ratio bias, resulting in a shortage of women? This is a possibility. Because of menopause and our exceptionally long lives, the sex ratio of reproductive-aged individuals in humans is generally male-biased52. Therefore, as a consequence of the evolution of increasing longevity, coupled with reproductive cessation in women54, ancestral males likely faced an increasingly male-biased sex ratio8, altering the selective arena for payoffs to mating strategies.

Our findings also speak to the current debate regarding the relative emergence of monogamy and cooperative breeding in human evolution54. The monogamy hypothesis suggests that pairbonding and male care preceded the emergence of cooperative breeding in our lineage55. Thus, much of our unique life history can be attributed to male investment. However, cooperative breeding proponents argue that the assistance of others (not the father) increased the fertility of mothers, decreased the mortality of offspring, and allowed for the suite of human life-history traits to evolve3,56,57. While we do not engage this debate directly, we find monogamy in response to partner scarcity. If female scarcity in humans arose primarily due to the extension of the lifespan, then cooperative breeding likely preceded monogamy in humans.

Lastly, for paternal care to emerge in our models, the benefits to care need to be high (e.g., a doubling of offspring survivorship). There are a couple of reasons to doubt how biologically appropriate this parameter estimate is. First, until paternal care has been under selection, it is likely to be inefficient, quite variable in returns, unreliable and possibly of little benefit58. Therefore, requiring such high payoffs for care to emerge raises concerns about its relevance to the evolution of monogamy. Second, in a recent cross-cultural review looking to paternal effects on child survival, only a third of studies found any beneficial outcome to father presence59. This is obviously quite surprising given how human pairbonds are typically described as a cooperative system of joint production to meet household needs2,17. With this example we do not seek to challenge whether or not males invest (e.g., paternal care may have benefits other than increasing offspring survival, such as elevating quality60) but use it to simply highlight the requirements for paternal care to evolve in our models.

Accordingly, in humans, we contend that the transition from males mating multiply to providing paternal care possibly passed through an intermediate step of male mate guarding in response to partner rarity. This interpretation is consistent with recent phylogenetic analyses of primate social organization, indicating that bonded relationships (i.e., pair-living) derived from an earlier state of multi-male/multi-female groups61,62. Pairbond formation through mate guarding provides a mechanism to ensure paternity certainty and a possible avenue to open up paternal care to selection. Once pairbond duration lengthens, the reproductive interests of males and females may become aligned. As a derived trait, monogamy may be stabilized through payoffs to infanticide protection23 as well as by increasing the interdependence of pairbonded individuals and evolved social mechanisms to maintain the sexual division of labor and the specialization of care tasks63. Upon considering the competing equilibria of mate-guarding and parental-care (Fig. 3c), one intriguing possibility is that once PC populations with elevated female fertility and greater degrees of social cooperation emerge, these strategies may become favored and increase in frequency through multilevel selection32.

In conclusion, as members of the hominin line began living longer, a transition from a female- to male-bias in the sex ratio was a likely outcome. In response to male abundance, following our model results, mate guarding by males was favored. As males consistently pairbonded and paternity certainty was assured, it became possible for selection to operate on variation across males in the amount of paternal care offered.

Methods

Mathematical description of the model

As mentioned above, here we investigate the evolution of three male strategies: PC, MG, and MM, with respective frequencies p, q , and 1 − p − q . The mating success of each male will depend on the ratio of males and females in the mating pool at time t , ( Mt /Ft), and the frequency of the three strategies in a large population. Our approach diverges from previous work on this topic, particularly that mating opportunities are dependent on partner availability.

The reproductive payoffs are structured such that each male enters the mating pool multiple times during its lifetime (Fig. 1), with future benefits discounted by the probability of survival. The sum of these benefits is the fitness of each strategy.

Paternal Care strategy

For each time period, PC males will pair with a female with probability yt = min [ Ft/Mt, 1] and give an added survival benefit to offspring, c . Since PC males do not guard there is a possibility of cuckoldry by MM males. If u is the probability of male survival from one period to the next, the fitness of the PC strategy becomes,

where ht is the probability of the PC male providing care to offspring not his own. The expression simplifies to,

To find ht, the probability of cuckoldry, we account for the relative frequency of PC and MM males ( p’ and (1− p’ ), respectively), the probability of conception per mating bout ( b ), the willingness of females to engage in extra-pair mating ( k ), and the probability of a female encountering another PC or MM male ( at). In the Supporting Information we show ht to be

Multiple Mating Strategy

MM males attempt to mate with multiple females in each time period, such that the fitness benefit zt is gained through shared paternity across available females not being guarded or paired to a PC male. Further, if there are PC males in the population, then cuckoldry will provide added benefits to the MM strategy with gt being the expected number of cuckold events per MM male. The fitness of the MM strategy becomes,

simplifying to

Since the number of females paired with a PC male is ytptMt the maximum possible paternity that an MM male may gain through cuckoldry is,

and adjusting for the probability a PC male becomes a cuckold yields,

Since the number of females paired to PC and MG males is ytptMt and ytqtMt, the number of females for which paternity if shared among MM males is Ft−ytMt(pt + qt). Thus,

Mate Guarding strategy

Following previous theoretical work on the topic9 and empirical results linking paternity certainty to time spend guarding30, fitness benefits to MG males depend solely on the probability of finding one female, yt, after which the male guards the female successfully through his lifetime:

Above simplifies to

When simulating the fitness of all strategies as they accumulate through time (Fig. 1), they approach an asymptote well before t = 100. Therefore in all simulations below, we calculate fitness up to this time point.

Adult Sex Ratio dynamics

We assume a discrete time process t = [0, 1, … ] where the fraction of available males to females may change throughout a male’s lifetime. It will change if there are MG males in the population, otherwise it will remain the same as initially determined in each time period. Thus without a significant number of Mate Guarding males (q ≈ 0) then Mt = M0 and Ft = F0, and the fitness of the strategies specified above simplifies greatly. If there are MG males in the population then Mt and Ft will change through time as females encountering MG males leave the mating pool. Once MG males are fully gone, then the sex ratio of available females to males is constant. Importantly, the effects MG males have on the operational sex ratio (i.e., those available to mate; OSR) varies both with the ASR and their frequency. In a male-biased ASR, when mate guarding males are common, they reduce the numbers of available females to near 0. However, the effect MG males have on the OSR is much different at female-biased ASRs. These males, by removing themselves from the population, increase the relative numbers of females available to, for example, MM males (see SI).

If there are Ft females and qtMt MG males in the population and Mt > Ft, then the probability of a female becoming newly guarded by a male is qt, making the average number of females being newly guarded by a male is qtFt. With Mt and Ft being the number of males and females in the mating pool at time t , and qt the frequency of non-paired MG males, then

In Figs 2 and 3 we investigate contrasting initial sex ratios that are female-biased ( M0 = 100, F0 = 150) and male-biased ( M0 = 150, F0 = 100). In Fig. 4 we vary the ASR along a continuous scale.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Schacht, R. and Bell, A. V. The evolution of monogamy in response to partner scarcity. Sci. Rep. 6, 32472; doi: 10.1038/srep32472 (2016).

References

Chapais, B. Monogamy, strongly bonded groups, and the evolution of human social structure. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 22, 52–65, doi: 10.1002/evan.21345 (2013).

Kaplan, H., Hill, K., Lancaster, J. & Hurtado, A. M. A theory of human life history evolution: Diet, intelligence, and longevity. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 9, 156–185, doi: 10.1002/1520-6505 (2000).

Hrdy, S. B. Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding. (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009).

Hawkes, K. In Kinship and Behavior in Primates (eds B. Chapais & C. Berman ) 443–473 (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Hawkes, K., Rogers, A. R. & Charnov, E. L. The male’s dilemma: increased offspring production is more paternity to steal. Evol Ecol 9, 662–677 (1995).

Gavrilets, S. Human origins and the transition from promiscuity to pair-bonding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 9923–9928, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200717109 (2012).

Harts, A. M. & Kokko, H. Understanding promiscuity: when is seeking additional mates better than guarding an already found one? Evolution 67, 2838–2848, doi: 10.1111/evo.12163 (2013).

Coxworth, J. E., Kim, P. S., McQueen, J. S. & Hawkes, K. Grandmothering life histories and human pair bonding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 11806–11811, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1599993112 (2015).

Fromhage, L., Elgar, M. A. & Schneider, J. M. Faithful without Care: The Evolution of Monogyny. Evolution 59, 1400–1405, doi: 10.2307/3449163 (2005).

Gurven, M. & Hill, K. Why Do Men Hunt? A Reevaluation of “Man the Hunter” and the Sexual Division of Labor. Current Anthropology 50, 51–74 (2009).

Kleiman, D. G. Monogamy in mammals. Q Rev Biol 52, 39–69 (1977).

Trivers, R. L. In Sexual selection and the Descent of Man, 1871–1971 (ed. B. Campbell ) 136–179 (Aldine, 1972).

Lessells, C. In Levels of selection in evolution (ed. L. Keller ) 75–99 (Princeton University Press, 1999).

Houston, A. I., Székely, T. & McNamara, J. M. Conflict between parents over care. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20, 33–38, doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.10.008 (2005).

Borgerhoff Mulder, M. & Rauch, K. L. Sexual conflict in humans: Variations and solutions. Evolutionary Anthropology 18, 201–214, doi: 10.1002/evan.20226 (2009).

Clutton-Brock, T. H. & Parker, G. A. Potential Reproductive Rates and the Operation of Sexual Selection. The Quarterly Review of Biology 67, 437–456, doi: 10.2307/2832015 (1992).

Washburn, S. & Lancaster, C. In Man the hunter (eds R. Lee & L. DeVore ) 293–320 (Aldine de Gruyter, 1968).

Lancaster, J. & Lancaster, C. In Parenting across the lifespan: biosocial dimensions (eds J. B. Lancaster, J. Altmann, A. S. Rossi & L. R. Sherrod ) 187–205 (Aldine de Gruyter, 1987).

Brotherton, P. & Komers, P. In Monogamy: Mating strategies and partnerships in birds, humans and other mammals (eds U. Reichard & C. Boesch ) (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Mathews, L. M. Tests of the mate-guarding hypothesis for social monogamy: male snapping shrimp prefer to associate with high-value females. Behav Ecol 14, 63–67, doi: 10.1093/beheco/14.1.63 (2003).

Lukas, D. & Clutton-Brock, T. H. The Evolution of Social Monogamy in Mammals. Science 341, 526–530, doi: 10.1126/science.1238677 (2013).

Van Schaik, C. P. & Dunbar, R. I. M. The Evolution of Monogamy in Large Primates: a New Hypothesis and Some Crucial Tests. Behaviour 115, 30–61, doi: 10.1163/156853990X00284 (1990).

Opie, C., Atkinson, Q. D., Dunbar, R. I. M. & Shultz, S. Male infanticide leads to social monogamy in primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307903110 (2013).

Wittenberger, J. F. & Tilson, R. L. The Evolution of Monogamy: Hypotheses and Evidence. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 11, 197–232 (1980).

Rutberg, A. T. The evolution of monogamy in primates. J Theor Biol 104, 93–112 (1983).

Komers, P. E. & Brotherton, P. N. Female space use is the best predictor of monogamy in mammals. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 264, 1261–1270 (1997).

Kappeler, P. M. Lemur behaviour informs the evolution of social monogamy. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 29, 591–593, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.09.005 (2014).

Kokko, H. & Jennions, M. D. Parental investment, sexual selection and sex ratios. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 21, 919–948, doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01540.x (2008).

Grafen, A. & Ridley, M. A model of mate guarding. Journal of Theoretical Biology 102, 549–567, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193 (83)90390-9 (1983).

Komdeur, J. Mate guarding in the Seychelles warbler is energetically costly and adjusted to paternity risk. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 268, 2103–2111, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1750 (2001).

Gnoth, C., Godehardt, G., Godehardt, E., Frank‐Herrmann, P. & Freundl, G. Time to pregnancy: results of the German prospective study and impact on the management of infertility. Human Reproduction 18, 1959–1966 (2003).

Bell, A. V., Hinde, K. & Newson, L. Who Was Helping? The Scope for Female Cooperative Breeding in Early Homo. Plos One 8, e83667, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083667 (2013).

Boyd, R. & Richerson, P. J. Group Selection among Alternative Evolutionarily Stable Strategies. J Theor Biol 145, 331–342 (1990).

Clutton-Brock, T. H. & Vincent, A. C. J. Sexual selection and the potential reproductive rates of males and females. Nature 351, 58–60 (1991).

Kokko, H. & Jennions, M. D. In The Evolution of Parental Care (eds N. Royle, P.T. Smiseth & M. Kölliker ) 101–116 (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Schacht, R. & Borgerhoff Mulder, M. Sex Ratio Effects on Reproductive Strategies in Humans. Royal Society Open Science 2 (2015).

Guttentag, M. & Secord, P. Too Many Women? (Sage, 1983).

Pedersen, F. Secular trends in human sex ratios. Human Nature 2, 271–291, doi: 10.1007/bf02692189 (1991).

Schacht, R. & Kramer, K. L. Patterns of family formation in response to sex ratio variation. PLOS ONE. 11(9) (2016).

Schacht, R., Rauch, K. L. & Borgerhoff Mulder, M. Too many men: the violence problem? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 29, 214–222, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.02.001 (2014).

Adimora, A. A. et al. Sex ratio, poverty, and concurrent partnerships among men and women in the United States: a multilevel analysis. Ann Epidemiol 23, 716–719, doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.08.002 (2013).

Pouget, E. R., Kershaw, T. S., Niccolai, L. M., Ickovics, J. R. & Blankenship, K. M. Associations of Sex Ratios and Male Incarceration Rates with Multiple Opposite-Sex Partners: Potential Social Determinants of HIV/STI Transmission. Public Health Rep 125, 70–80 (2010).

Liker, A., Freckleton, Robert P. & Székely, T. Divorce and Infidelity Are Associated with Skewed Adult Sex Ratios in Birds. Curr Biol 24, 880–884, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.059 (2014).

Schwartz, S. K., Wagner, W. E. & Hebets, E. A. Spontaneous male death and monogyny in the dark fishing spider. vol. 9 (2013).

Carroll, S. P. & Corneli, P. S. Divergence in Male Mating Tactics between 2 Populations of the Soapberry Bug: Genetic Change and the Evolution of a Plastic Reaction Norm in a Variable Social-Environment. Behav Ecol 6, 46–56 (1995).

Carroll, S. & Loye, J. Male-biased sex ratios, female promiscuity, and copulatory mate guarding in an aggregating tropical bug,Dysdercus bimaculatus. J Insect Behav 3, 33–48, doi: 10.1007/bf01049193 (1990).

Beltran, S. & Boissier, J. Male-biased sex ratio: why and what consequences for the genus Schistosoma? Trends in parasitology 26, 63–69, doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.11.003 (2010).

Mathews, L. M. Tests of the mate-guarding hypothesis for social monogamy: does population density, sex ratio, or female synchrony affect behavior of male snapping shrimp (Alpheus angulatus)? Behav Ecol Sociobiol 51, 426–432, doi: 10.1007/s00265-002-0465-3 (2002).

Donald, P. F. Adult sex ratios in wild bird populations. Ibis 149, 671–692, doi: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.2007.00724.x (2007).

Liker, A., Freckleton, R. P. & Szekely, T. The evolution of sex roles in birds is related to adult sex ratio. Nat Commun 4, 1587, doi: 10.1038/ncomms2600 (2013).

Clutton-Brock, T. H., Harvey, P. H. & Rudder, B. Sexual dimorphism, socionomic sex ratio and body weight in primates. Nature 269, 797–800 (1977).

Marlowe, F. W. & Berbesque, J. C. The human operational sex ratio: Effects of marriage, concealed ovulation, and menopause on mate competition. Journal of Human Evolution 63, 834–842, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.09.004 (2012).

Székely, T., Liker, A., Freckleton, R. P., Fichtel, C. & Kappeler, P. M. Sex-biased survival predicts adult sex ratio variation in wild birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0342 (2014).

Kim, P. S., Coxworth, J. E. & Hawkes, K. Increased longevity evolves from grandmothering. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1751 (2012).

Kramer, K. L. & Russell, A. F. Kin-selected cooperation without lifetime monogamy: human insights and animal implications. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 29, 600–606, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.09.001 (2014).

Boomsma, J. J. Kin Selection versus Sexual Selection: Why the Ends Do Not Meet. Curr Biol 17, R673–R683, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.033 (2007).

Kramer, K. Maya Children: Helpers at the Farm. (Harvard University Press, 2005).

Petrie, M. & Lipsitch, M. Avian Polygyny is Most Likely in Populations with High Variability in Heritable Male Fitness. Vol. 256 (1994).

Sear, R. & Mace, R. Who keeps children alive? A review of the effects of kin on child survival. Evolution and Human Behavior 29, 1–18, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.10.001 (2008).

Bereczkei, T. & Csanaky, A. Evolutionary pathway of child development : Lifestyles of adolescents and adults from father-absent families. Human nature (Hawthorne, N.Y.) 7, 257–280, doi: 10.1007/bf02733397 (1996).

Shultz, S., Opie, C. & Atkinson, Q. D. Stepwise evolution of stable sociality in primates. Nature 479, 219–222, doi: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v479/n7372/abs/nature10601.html#supplementary-information (2011).

Kappeler, P. & Fichtel, C. The Evolution of Eulemur Social Organization. Int J Primatol, 1–19, doi: 10.1007/s10764-015-9873-x (2015).

Barta, Z., Székely, T., Liker, A. & Harrison, F. Social Role Specialization Promotes Cooperation between Parents. The American Naturalist 183, 747–761, doi: 10.1086/676014 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Monique Borgerhoff Mulder, Kristen Hawkes, Peter Kappeler, Karen Kramer and two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript and Alan Rogers for modeling advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S. conceived of the project; A.V.B. performed the modeling; R.S. and A.V.B. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Schacht, R., Bell, A. The evolution of monogamy in response to partner scarcity. Sci Rep 6, 32472 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32472

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32472

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Resemblance Reporting on Children: Sisters Are More Proactive than Brothers

Evolutionary Psychological Science (2022)

-

The Effects of the Mating Market, Sex, Age, and Income on Sociopolitical Orientation

Human Nature (2020)

-

Papa Don’t Preach?

Human Nature (2020)

-

Why Males Compete Rather Than Care, with an Application to Supplying Collective Goods

Bulletin of Mathematical Biology (2020)

-

Does the Quality of Mating Competitors Affect Socio-Political Attitudes? An Experimental Test

Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology (2020)