Abstract

Past epidemiologic studies have indicated that the ideal cardiovascular health (CVH) metrics are associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and stroke. Carotid artery stenosis (CAS) causes approximately 10% of ischemic strokes. The association between ideal CVH and extracranial CAS has not yet been assessed. In the current study, extracranial CAS was assessed by carotid duplex ultrasonography. Logistic regression was used to analyze the association between ideal CVH metrics and extracranial CAS. A total of 3297 participants (52.2% women) aged 40 years and older were selected from the Jidong community in China. After adjusting for sex, age and other potential confounds, the odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for extracranial CAS were 0.57 (0.39–0.84), 0.46 (0.26–0.80) and 0.29 (0.15–0.54) and for those quartiles, quartile 2 (9–10), quartile 3 (11) and quartile 4 (12–14), respectively, compared with quartile 1 (≤8). This negative correlation was particularly evident in women and the elderly (≥60 years). This cross-sectional study showed a negative correlation between the ideal CVH metrics and the prevalence of extracranial CAS in northern Chinese adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carotid artery stenosis (CAS) causes approximately 10% of ischemic strokes1. Approximately 7% of first ischemic strokes were associated with extracranial CAS2. Data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 (GBD2010) indicated that the leading cause of death in China is stroke3. Furthermore, previous studies have indicated that many patients with CAS have a greater risk of dying due to myocardial infarction (MI) than from stroke4,5. In the Framingham Heart Study, the prevalence of CAS in people aged 66 to 93 years was 7% in women and 9% in men6. CAS refers to an atherosclerotic narrowing specifically of the extracranial CAS, the internal CAS or the common CAS7. Genetic susceptibility may play a key role in the development of CAS and there may be different pathophysiologies for the different CAS locations8,9. However, there are other possible factors in the development of CAS, including differences in the prevalence of risk factors or of particular life styles across different ethnic populations10. Due to the high prevalence of extracranial CAS, the study of risk factors and protective measures for extracranial CAS has particular public health significance in China.

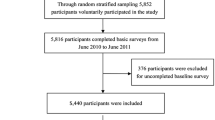

The American Heart Association (AHA) has defined ideal cardiovascular health (CVH) as including four ideal health behaviors (body mass index, physical activity, healthy diet and smoking status) and three ideal health factors (total cholesterol, blood pressure and fasting blood glucose)11. Worldwide, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain a major public health burden and are expected to increase over the next 10 years as the population ages11,12. Several studies have suggested that the ideal CVH metrics were remarkably negatively associated with the total incidence of CVD and stroke11,13,14,15. In addition, a study based on 5440 Chinese adults found a clear gradated negative relationship between a higher number of ideal CVH metrics and a lower prevalence of asymptomatic intracranial carotid artery stenosis (ICAS)16. However, the association between the ideal CVH metrics in the AHA definition and extracranial CAS is still unclear. Therefore, a cross-sectional analysis was conducted to explore this association in a northern Chinese cohort that consisted of 3297 adult participants.

Results

From the initial sample of 4428 participants, 369 participants were excluded because of physical disabilities or because they did not provide informed consents and 762 participants were excluded because of incomplete data on their health factors, health behaviors or other variables. Finally, 3297 participants were included in the final analysis.

Table 1 shows the basic characteristics of the participants stratified by sex.

Women tended to be younger, lower educated and of average income. Participants with heavy alcohol consumption were almost always male (99% vs 1%). In addition, parameters such as BMI, SBP, DBP, FPG and TG were higher in men, while TC was lower in men, compared to the values of those parameters in women.

Table 2 shows the association between each CVH metric and the prevalence of extracranial CAS.

After adjusting for sex, age, alcohol use, average monthly income of each family member, education level and the other six cardiovascular health metrics, we found that the ideal smoking status, blood pressure, total cholesterol and fasting blood glucose metrics were significantly associated with a lower prevalence of extracranial CAS (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.35–0.85, P = 0.007; OR = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.25–0.84, P = 0.012; OR = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.24–0.85, P = 0.014; OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.34–0.90, P = 0.017; respectively). In further stratified analyses, the negative associations of extracranial CAS with the ideal blood pressure and ideal total cholesterol were significant (P ≤ 0.05) in men but not in women and the negative correlation of extracranial CAS with the ideal total cholesterol and ideal fasting blood glucose were only found in middle-aged groups (40–60 years of age). Similarly, the negative correlation with the ideal smoking status was particularly evident in women and the elderly (≥60 years).

Table 3 shows the relationship between the total score of the ideal CVH metrics and the prevalence of extracranial CAS.

After adjusting for sex, age, alcohol use, average monthly income of each family member and education level, participants in the highest quartile of the ideal CVH metrics summary score had a lower prevalence of extracranial CAS compared to those in the lowest quartile of the summary score (OR = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.15–0.54, P < 0.001). The stratified analyses found that this significant negative correlation was still evident particularly in men (P < 0.001) and the elderly (≥60 years) (P < 0.001).

Discussion

The main strengths of the present study are as follows. 1) The preliminary analysis showed that the ideal smoking status, blood pressure, total cholesterol and fasting blood glucose metrics were significantly associated with a low prevalence of extracranial CAS in the total population compared to the poor group. 2) Our data indicated that individuals in the highest quartile of the total ideal CVH metrics had a 71% reduced risk of developing extracranial CAS compared to those in the lowest quartile, after adjusting for potential confounds (sex, age, alcohol use, average monthly income of each family member and education level). 3) A similar negative correlation was observed in subgroups of women and the elder (≥60 years). ECAS is a subclinical indicator for stroke and cerebrovascular diseases. The association between ECAS and CVD suggests that CVD may primarily contribute to ECAS and then lead to cerebrovascular diseases via subclinical cerebrovascular changes. To our knowledge, this study is novel in its exploration of the potential association between the ideal CVH and extracranial CAS in an adult Chinese population.

Previous studies have investigated the combined association of extracranial CAS prevalence and different risk factors on atherosclerosis. The Framingham Heart Study, a multivariate logistic regression model, showed that age, cigarette smoking, systolic blood pressure and cholesterol were independently related to carotid atherosclerosis6,17. Similar to previous studies17,18,19,20, we showed that the ideal metric of smoking status was inversely associated with extracranial CAS. In the Cardiovascular Health Study19, the severity of CAS was greater in current smokers than in former smokers and the severity of CAS was significantly associated with pack-years of exposure to tobacco. Similarly, the Framingham Heart Study found that extracranial CAS was correlated with the quantity of cigarettes smoked over time, especially in women17, which is consistent with our findings. Although the association in our study did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.086) in men, there was a highly significant trend across the total participants (P = 0.007). There was an OR of 1.33 (95% CI: 0.37–4.77) for intermediate smoking compared to sparse smoking that could have been caused by the small sample size of smokers, which could have led to insufficient statistical power.

According to our study, the ideal metrics of blood pressure, total cholesterol and fasting blood glucose had inverse relationships with extracranial CAS. Previous studies on risk factors for extracranial CAS also showed similar results17,21,22,23. The Framingham Heart Study indicated that there was a 2-fold increased risk of carotid stenosis for every 20 mmHg increase in SBP17. Sutton-Tyrrell et al. found that a SBP of ≥160 mmHg was the strongest independent predictor of extracranial CAS, especially in the elderly21. Our study confirmed this association, in men but not in women, a finding that can be explained by physique differences between the sexes. The MESA study24 showed that total cholesterol was strongly associated with a carotid plaque lipid core and the Framingham Heart Study17 found that the relative risk (RR) of CAS was >25% and increased approximately 1.1 for every 10 mg/dL increase in total cholesterol, which are findings that are both consistent with our results, particularly among middle-aged adults (40–60 years of age) compared to the elderly. Cholesterol levels often decline in the elderly, which may be a cause of the lower association in our study. In addition, our finding of a negative association between the ideal FPG and extracranial CAS is supported by results from the IRAS (Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study)25, suggesting that the progression of carotid atherosclerosis is accelerated in persons with type 2 diabetes and that this increased rate of atherosclerosis is partially explained by the atherogenic risk factor profile associated with diabetes. Similarly, the Cardiovascular Health Study23 also reported that diabetes was associated with carotid IMT and the severity of CAS. In the present study, significant negative correlations between the ideal CVH body mass index, physical activity or health diet metrics and extracranial CAS were not observed. The previous study also found that physical activity was not associated with carotid atherosclerosis26.

Previous studies found inverse associations between improving diet and weight management and the development of carotid atherosclerosis27,28,29, which was in contrast to our study. The present study indicated that there was no significant relationship between diet and CAS (OR 0.81, 95% CI: 0.46–1.43; in those with a poor diet score compared to those with an ideal diet score), which is contrary to a previous study (ref. 27) in regard to the OR value. This inconsistency may be explained by the following two reasons. First, the two studies used different definitions of ideal diets and in particular, the different ranges led to different cut-offs for ideal, intermediate and poor diet scores. Second, the association between the ideal diet score and CAS may be smaller in a Chinese population than in other populations and therefore, our study may not have enough statistical power to detect the association (OR 0.81, 95% CI: 0.46–1.43, P = 0.28). In our study, participants were Han-ethnic Chinese, who probably have different physiques and lifestyles than other ethnic populations.

Our study indicated a significant negative correlation between the ideal CVH metrics and the prevalence of extracranial CAS. Extracranial CAS has several causes including atherosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), cystic medial necrosis, arteritis and dissection, with the most frequent cause being atherosclerosis29. Atherosclerosis is a systemic disease and patients with extracranial CAS typically have an escalated risk of other adverse cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction (MI), peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and death30,31,32. Risk factors associated with extracranial CAS, such as cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes and hypercholesterolemia, are the same as those for atherosclerosis located elsewhere, but differences exist in the relative contribution to the risk in the various vascular beds. Therefore, it makes sense that maintaining the ideal CVH metrics may be the most effective means to avoid extracranial CAS. This is the idea of primordial prevention11.

There are potential limitations of our study. First, the Jidong community involves mainly regional populations, so the results may not be generalizable across the nation due to geographic variations and different educational, economic and cultural backgrounds. Second, this study was a cross-sectional study that did not have the capacity to evaluate causal relationships between the ideal CVH metrics and extracranial CAS. Therefore, our study can only speculate that maintaining CVH may be beneficial in reducing the risk of atherosclerosis. Prospective studies are needed to further examine the causality links. Third, carotid duplex ultrasonography is a noninvasive vascular test that may underestimate the severity of stenosis (especially in cases of less than 50% stenosis)33. However, carotid duplex ultrasonography is widely used for initial evaluations and to estimate CAS and experienced sonographers are able to provide accurate and relatively inexpensive assessment of CAS via this method34. Fourth, the cardiovascular behavior measures, such as physical activity, smoking and dietary intake, were from self-reported questionnaires, so misclassification was possible, especially in regard to diet and physical activity. Finally, extracranial CAS involves complex mechanisms like different etiologies and pathogeneses, which our study did not identify. Therefore, different potential risk factors and preventive strategies for CAS need to be explored further.

In conclusion, the ideal CVH metrics were significantly associated with the prevalence of extracranial CAS in northern Chinese adults, especially in women and the elderly (≥60 years). This negative correlation indicates that maintaining an ideal CVH may be of great value in preventing extracranial CAS. Prospective studies are needed to further investigate these questions.

Method

Study Design and Participants

From July 2013 to August 2014, 9,078 participants (man 4,768, aged 18–82 years old) were enrolled in the study cohort and comprised employees (including those who were retired) and their family members from the Jidong Co. Ltd, a large Oilfield in Hebei Province, China. In our study, the inclusion criteria were: (1) aged 40 years or older; and (2) without stroke, transient ischemic attack and myocardial infarction (MI). Among the 9078 potential participants, 4428 satisfied the above inclusion criteria. In addition, participants were excluded from this study according to following exclusion criteria: (1) incomplete data on health factors or behaviors, or not providing informed consent and (2) physical disabilities.

Ethics Statement

The study was performed according to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration, with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Jidong Oilfield Hospital. All participants agreed to study participation and provided informed consents.

Assessment of Cardiovascular Health Metrics

Information about smoking, physical activity and dietary intake was collected via questionnaires. Dietary habits were assessed with a brief semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire35,36, which had definitions similar to the AHA definitions of dietary habits (see Table 4). The definition of an ideal diet score in this study was as reported in our previous publication37. According to the AHA definitions11, we further categorized smoking status, physical activity and dietary intake into three groups: “ideal”, “intermediate” or “poor”. Smoking was classified as ideal (never or quit smoking >12 months previously), intermediate (quit smoking ≤12 months ago), or poor (currently smoking); physical activity was classified as ideal (≥150 min/week of moderate intensity or ≥75 min/week of vigorous intensity), intermediate (1–149 min/week of moderate intensity or 1–74 min/week of vigorous intensity), or poor (none). Healthy diet behaviors were classified as ideal (4–5 components), intermediate (2–3 components) or poor (0–1 component).

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated based on the weight (accurate to 0.1 kg) and height (accurate to 0.1 cm) measurements of the participants, as body weight (kg)/the square of height (m2). Participants’ blood pressure was measured twice by experienced research nurses following 5 minutes of rest in a seated position using a mercury sphygmomanometer with a cuff of the appropriate size. The averages of the two systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) readings were used for the analysis. If the deviation of the two measurements was more than 5 mm Hg, an additional reading was taken and the average of the three readings was used. All blood pressure was measured using the right arm. Hypertension was defined as the presence of a history of hypertension, using antihypertensive medication, a SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg, or a DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg. According to the AHA definitions11, BMI was classified as ideal (<25 kg/m2), intermediate (25 to 29.9 kg/m2) or poor (≥30 kg/m2); blood pressure was classified as ideal (SBP < 120 mmHg and DBP < 80 mmHg and untreated), intermediate (120 mm Hg ≤ SBP ≤ 139 mmHg, 80 mmHg ≤ DBP ≤ 89 mmHg, or treated to SBP/DBP < 120/80 mmHg), or poor (SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, DBP ≥ 90 mmHg, or treated to SBP/DBP > 120/80 mmHg).

Blood samples were collected from the antecubital vein by trained research nurses in the morning following overnight fasting and were transfused into vacuum tubes containing EDTA. The tubes were then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3000 rotations per minute at 25 °C. After separation, plasma samples were used within 4 hours. All biochemical variables, including total cholesterol and fasting blood glucose, were measured using an autoanalyzer (Olympus, AU400, Japan) in the central laboratory of the Jidong Oilfield Hospital. According to the AHA definitions11, fasting blood glucose was classified as ideal (<100 mg/dL and untreated), intermediate (100 to 125 mg/dL or treated to <100 mg/dL), or poor (≥126 mg/dL or treated to ≥100 mg/dL); total cholesterol was classified as ideal (<200 mg/dL and untreated), intermediate (200 to 239 mg/dL or treated to <200 mg/dL), or poor (≥240 mg/dL or treated to ≥200 mg/dL).

Assessment of Extracranial Carotid Artery Stenosis

All participants (≥40 years) underwent carotid duplex ultrasonography in a supine position, with their head turned to the contralateral side. All carotid scans were performed by two independent sonographers with ultrasounds. The sonographers were blind to the baseline information of the participants. Carotid duplex ultrasound modalities combined 2-dimensional real-time imaging with Doppler flow analysis to evaluate the vessels of interest (typically the cervical portions of the common and internal carotid arteries) and to measure blood flow velocity. Extracranial CAS was defined by a peak systolic blood flow velocity ≥125 cm/s and a vertical artery peak systolic blood flow velocity of ≥170 cm/s in the common carotid artery or internal carotid artery. Extracranial CAS was graded according to the diagnostic criteria identified by the Society of Radiologists in the Ultrasound Consensus Conference in 2003. In our study, the degree of CAS was classified as normal (no stenosis) or stenosis (<50% stenosis, ≥50% stenosis or occlusion) involving at least one internal or common CAS.

Assessment of Potential Covariates

Biographical information (age, race, sex, education level, average monthly income of each family member, alcohol use and disease history) was collected via questionnaires at the baseline visit. Participants were divided into two groups according to age: 40–59 years and ≥60 years. Participants’ education level was categorized as “illiterate or primary”, “middle/high school” or “college graduate or above”. The average monthly income of each family member was reported to be “ ≤¥3,000”, “¥3,001–5,000” or “ ≥¥5,001”. Heavy alcohol consumption was defined as a daily intake of at least 100 ml of liquor (equivalent to 240 ml of wine or 720 ml of beer) for more than a year. The existence of a history of stroke or MI was defined as any self-reported previous physician’s diagnosis of stroke or MI.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Categorical variables were described using percentages and compared with Chi square tests. Continuous variables were described using means (standard deviation [SD]) and compared with ANOVAs. Logistic regression was used to estimate the prevalence of extracranial CAS across the subgroups of each ideal CVH metric by calculating the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Adjustments were made for five variables (sex, age, alcohol use, average monthly income of each family member and education level) that were identified as potential confounds of the risk factors for extracranial CAS14,16,38. In addition, the composite score of the seven CVH metrics was quantified by adding the following numeric values assigned to each component based on category: 0 = poor, 1 = intermediate and 2 = ideal39. The prevalence of extracranial CAS was analyzed using the total score of the CVH metrics inserted into the models as quartiles (with the lowest quartile as the reference), using logistic regression. All statistical tests were 2-sided and significance levels were 0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hao, Z. et al. The Association between Ideal Cardiovascular Health Metrics and Extracranial Carotid Artery Stenosis in a Northern Chinese Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sci. Rep. 6, 31720; doi: 10.1038/srep31720 (2016).

References

Goldstein, L. B. et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 42, 517–84 (2011).

White, H. et al. Ischemic stroke subtype incidence among whites, blacks and Hispanics: the Northern Manhattan Study. Circulation 111, 1327–31 (2005).

Yang, G. et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 381, 1987–2015 (2013).

Wiebers, D. O., Whisnant, J. P., Sandok, B. A. & O’Fallon, W. M. Prospective comparison of a cohort with asymptomatic carotid bruit and a population-based cohort without carotid bruit. Stroke 21, 984–8 (1990).

Norris, J. W., Zhu, C. Z., Bornstein, N. M. & Chambers, B. R. Vascular risks of asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Stroke 22, 1485–90 (1991).

Fine-Edelstein, J. S. et al. Precursors of extracranial carotid atherosclerosis in the Framingham Study. Neurology 44, 1046–50 (1994).

Jonas, D. E. et al. Screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 161, 336–46 (2014).

Feldmann, E. et al. Chinese-white differences in the distribution of occlusive cerebrovascular disease. Neurology 40, 1541–45 (1990).

Duggirala, R., Gonzalez Villalpando, C., O’Leary, D. H., Stern, M. P. & Blangero, J. Genetic basis of variation in carotid artery wall thickness. Stroke 27, 833–7 (1996).

Sacco, R. L., Kargman, D. E., Gu, Q. & Zamanillo, M. C. Race-ethnicity and determinants of intracranial atherosclerotic cerebral infarction. The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Stroke 26, 14–20 (1995).

Writing Group, M. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121, e46–e215 (2010).

Sacco, R. L. The 2006 William Feinberg lecture: shifting the paradigm from stroke to global vascular risk estimation. Stroke 38, 1980–87 (2007).

Folsom, A. R. et al. Community prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health, by the American Heart Association definition and relationship with cardiovascular disease incidence. J Am Coll Cardiol 57, 1690–6 (2011).

Dong, C. et al. Ideal cardiovascular health predicts lower risks of myocardial infarction, stroke and vascular death across whites, blacks and hispanics: the northern Manhattan study. Circulation 125, 2975–84 (2012).

Wu, S. et al. Prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health and its relationship with the 4-year cardiovascular events in a northern Chinese industrial city. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 5, 487–93 (2012).

Zhang, Q. et al. Ideal cardiovascular health metrics on the prevalence of asymptomatic intracranial artery stenosis: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 8, e58923 (2013).

Wilson, P. W. et al. Cumulative effects of high cholesterol levels, high blood pressure and cigarette smoking on carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med 337, 516–22 (1997).

Sharrett, A. R. et al. Smoking, diabetes and blood cholesterol differ in their associations with subclinical atherosclerosis: the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis 186, 441–7 (2006).

Tell, G. S. et al. Correlates of blood pressure in community-dwelling older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Collaborative Research Group. Hypertension 23, 59–67 (1994).

Howard, G. et al. Cigarette smoking and other risk factors for silent cerebral infarction in the general population. Stroke 29, 913–7 (1998).

Sutton-Tyrrell, K., Alcorn, H. G., Wolfson, S. K. Jr., Kelsey, S. F. & Kuller, L. H. Predictors of carotid stenosis in older adults with and without isolated systolic hypertension. Stroke 24, 355–61 (1993).

Sacco, R. L. et al. Race-ethnicity and determinants of carotid atherosclerosis in a multiethnic population. The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Stroke 28, 929–35 (1997).

O’Leary, D. H. et al. Distribution and correlates of sonographically detected carotid artery disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. The CHS Collaborative Research Group. Stroke 23, 1752–60 (1992).

Wasserman, B. A. et al. Risk factor associations with the presence of a lipid core in carotid plaque of asymptomatic individuals using high-resolution MRI: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Stroke 39, 329–35 (2008).

Wagenknecht, L. E. et al. Diabetes and progression of carotid atherosclerosis: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23, 1035–41 (2003).

Kronenberg, F. et al. Influence of leisure time physical activity and television watching on atherosclerosis risk factors in the NHLBI Family Heart Study. Atherosclerosis 153, 433–43 (2000).

Lakka, T. A., Lakka, H. M., Salonen, R., Kaplan, G. A. & Salonen, J. T. Abdominal obesity is associated with accelerated progression of carotid atherosclerosis in men. Atherosclerosis 154, 497–504 (2001).

Shai, I. et al. Dietary intervention to reverse carotid atherosclerosis. Circulation 121, 1200–8 (2010).

Brott, T. G. et al. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation 124, e54–130 (2011).

Craven, T. E. et al. Evaluation of the associations between carotid artery atherosclerosis and coronary artery stenosis. A case-control study. Circulation 82, 1230–42 (1990).

Sabeti, S. et al. Progression of carotid stenosis detected by duplex ultrasonography predicts adverse outcomes in cardiovascular high-risk patients. Stroke 38, 2887–94 (2007).

Rundek, T. et al. Carotid plaque, a subclinical precursor of vascular events: the Northern Manhattan Study. Neurology 70, 1200–7 (2008).

Grant, E. G. et al. Carotid artery stenosis: grayscale and Doppler ultrasound diagnosis–Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound consensus conference. Ultrasound Q19, 190–8 (2003).

Howard, G. et al. An approach for the use of Doppler ultrasound as a screening tool for hemodynamically significant stenosis (despite heterogeneity of Doppler performance). A multicenter experience. Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study Investigators. Stroke 27, 1951–7 (1996).

Li, L. M. et al. A description on the Chinese national nutrition and health survey in 2002. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi 26, 478–84 (2005).

Zhuang, M. et al. Reproducibility and relative validity of a food frequency questionnaire developed for adults in Taizhou, China. PLoS One 7, e48341 (2012).

Li, Z. et al. Association between Ideal Cardiovascular Health Metrics and Depression in Chinese Population: A Cross-sectional Study. Sci Rep 5, 11564 (2015).

Juonala, M. et al. Life-time risk factors and progression of carotid atherosclerosis in young adults: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study. Eur Heart J 31, 1745–51 (2010).

Shay, C. M. et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adolescents: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2005–2010. Circulation 127, 1369–76 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by research grants from the National 12th Five-Year Major Projects of China (grant number 2012BAI37B03) and Recovery Medical Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H., Y.Z., R.Z., J.H. and Y.Z. conceived and designed this study, Z.H., Y.Z., Y.L. and J.Q. directed data analysis, Z.H. and Y.Z. writing the paper. Z.H., Y.Z., Y.L. and J.Z. prepare the database and reviewed the paper. R.Z., J.H. and Y.Z. conducted the quality assurance, reviewed and edited the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, Y. et al. The Association between Ideal Cardiovascular Health Metrics and Extracranial Carotid Artery Stenosis in a Northern Chinese Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sci Rep 6, 31720 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31720

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31720

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Association between metabolic score of visceral fat and carotid atherosclerosis in Chinese health screening population: a cross-sectional study

BMC Public Health (2024)

-

Ideal Cardiovascular Health Metrics on the New Occurrence of Peripheral Artery Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study in Northern China

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Relationship of ideal cardiovascular health metrics with retinal vessel calibers and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness: a cross-sectional study

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2018)

-

Ideal Cardiovascular Health Metrics Associated with Reductions in the Risk of Extracranial Carotid Artery Stenosis: a Population-based Cohort Study

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Coronary Artery Calcification in a Northern Chinese Population: a Cross Sectional Study

Scientific Reports (2017)