Abstract

Media literacy tips typically encourage people to be skeptical of the news despite the small prevalence of false news in Western democracies. Would such tips be effective if they promoted trust in true news instead? A pre-registered experiment (N = 3919, US) showed that Skepticism-enhancing tips, Trust-inducing tips, and a mix of both tips, increased participants’ sharing and accuracy discernment. The Trust-inducing tips boosted true news sharing and acceptance, the Skepticism-enhancing tips hindered false news sharing and acceptance, while the Mixed tips did both. Yet, the effects of the tips were more alike than different, with very similar effect sizes across conditions for true and false news. We experimentally manipulated the proportion of true and false news participants were exposed to. The Trust and Skepticism tips were most effective when participants were exposed to equal proportions of true and false news, while the Mixed tips were most effective when exposed to 75% of true news - the most realistic proportion. Moreover, the Trust-inducing tips increased trust in traditional media. Overall, we show that to be most effective, media literacy tips should aim both to foster skepticism towards false news and to promote trust in true news.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the digital age, discerning between misinformation and credible news is vital. Global concerns about the spread of misinformation have prompted policymakers to seek effective solutions. These strategies aim to diminish the public’s tendency to believe and disseminate misinformation and have evolved from broad regulatory approaches to more scalable individual-level interventions. However, there is a growing concern that while media literacy interventions are effective in safeguarding against misinformation, they may inadvertently escalate skepticism towards factual news1,2. This unintended consequence is particularly problematic in Western democracies for three main reasons.

First, the majority of online news stories people consume are genuine and originate from reliable sources3,4,5,6. Given the paucity of misinformation in people’s news diet, interventions that reduce the acceptance of misinformation are thus bound to have small effects6. Second, trust in the news is low worldwide and a growing number of people avoid the news, which—combined with low levels of political interest—leaves a substantial part of the population largely uninformed about political matters and current events7,8. Moreover, while people are good at spotting false news when prompted to do so, they show high levels of skepticism towards true news1,9. Third, disinterest in news and the small portion of misinformation in people’s online news diet suggest that many more hold misperceptions because they are not exposed to reliable information rather than because they consume and accept misinformation3. This suggests that while the fight against misinformation is necessary, it is by no means sufficient to reduce misperceptions and to improve the information ecosystem. To be most effective, the fight against misperceptions should go hand in hand with the promotion of reliable information.

Following the above, our study makes two primary contributions: first, we employ survey experiments in the United States (N = 3919) to assess the effectiveness of three distinct media literacy interventions—focusing on skepticism, trust, and a balanced approach—on the ability to discern misinformation. Second, we experimentally manipulated the proportion of false and true news rated by participants, addressing whether these variations can significantly influence the efficacy of media literacy interventions.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of interventions against misinformation: reactive interventions, including fact-checking and labeling, and proactive interventions, such as inoculation, accuracy prompts, and media literacy efforts. Proactive interventions are particularly praised for their role in enhancing individual autonomy and promoting political engagement while respecting the principles of free press10. Both reactive and proactive interventions aim to increase the accuracy of public beliefs and to enhance the overall quality of the information ecosystem.

Yet, misinformation is only one side of the equation: to make informed decisions, people must not only reject false and misleading information but also embrace accurate and reliable information6,11. For instance, people may refuse to get vaccinated because they believe misinformation, or simply because they do not trust reliable information about the vaccines. To improve the accuracy of people’s beliefs and the quality of the information ecosystem, it is thus necessary to both counter misinformation and foster reliable information. Before the 2016 US Presidential elections and the 2020 COVID pandemic, scholars examined media literacy interventions as a way of educating people more generally on journalistic practices12, or—more specifically—on spotting media violence13 and biases in news reporting14. Yet,—with the exception of the accuracy prompt15—most current interventions aimed at reducing misperceptions and improving decision-making disproportionately focus on misinformation at the expense of reliable information16. This is the case despite the lack of evidence that the acceptance of misinformation is more damaging than the rejection of reliable information6,11. We show that most current interventions could benefit from more explicitly promoting reliable information, while additionally—but not solely—targeting misinformation.

The role of digital media platforms in countering misinformation has come under scrutiny. Soft measures like source labels, while minimally impacting free speech, also exhibit limited effectiveness17. Concerns about misinformation on social media have prompted public institutions, including the European Union, to heavily invest in media literacy initiatives like the European Union Media Literacy Agenda. These programs aim to foster long-term critical thinking18,19,20 but prove less beneficial for digital platforms that require rapid and scalable interventions. Traditional media literacy programs, which focus on developing knowledge and skills to counter misinformation, may not effectively address emotional and impulsive online behaviors, which align more with immediate attitudinal reactions than with knowledge and skills21. Moreover, skill-based programs may struggle to keep pace with the fast-paced and continuous evolution of digital media environments22, which calls for more agile approaches to train citizens to discern news accurately23,24.

Media literacy tips embrace the view of agile interventions that directly engage with the acceptance and sharing of information. They often employ short-form advice25 consisting of actionable behaviors—for example, encouraging verification of news sources—and responsible attitudes—such as inviting to be skeptical of nonprofessional news sources. Such media literacy tips typically raise awareness about misinformation1,26 and promote mindfulness and skepticism on social media16. For instance, in 2017, Facebook employed media literacy tips at the top of users’ news feed in 14 countries to help them identify false news. The advice ranged from “Be skeptical of headlines” to “Some stories are intentionally false”. These tips were shown to reduce the perceived accuracy of false news headlines but also, to some extent, of mainstream news headlines25. Similarly, a recent study testing the effect of health media literacy tips raising awareness about manipulation techniques, such as “Biased, Overblown, Amateur, Sales-focused, Taken out of context”, increased skepticism in both accurate and inaccurate news headlines27. These findings are consistent with a growing body of research showing that, while well-intended, media literacy interventions targeting misinformation can inadvertently undermine acceptance of true and reliable information26,28,29,30. Many other interventions against misinformation were shown to increase skepticism in true news1,2,31 or to decrease trust in typically reliable actors such as professional media and scientists32.

These concerns are not new. Two decades ago, long before the recent misinformation hype, scholars were concerned that media literacy interventions—even when not specifically targeted at misinformation—may fuel media cynicism10. Indeed, “[f]ostering skepticism toward news and information, while avoiding cynicism, is a longstanding goal and challenge of media literacy education” [10,33,34, p. 151]. In recent years, a lot of progress has been made on this front. On the methodological side, it has now become clear that researchers should measure treatment effects on both misinformation (or information people should be skeptical of) and reliable information (or information people should accept11). On the statistical side, more sophisticated measures of discrimination, that account for response bias (e.g., participants rating everything as false), are being proposed and popularized31.

Negative spillovers from media literacy interventions are a significant concern since false news represents only a minor portion of the total news content to which people are exposed in Western democracies3,4,6,32,35,36,37. However, the vast majority of interventions against misinformation test participants with equal proportions of true and false news9. The standard 50/50 split raises concerns for two reasons. First, in real-world settings, individuals typically encounter about 5% false news and 95% true news6—a stark contrast to the balanced 50/50 split commonly used in misinformation discernment studies. Second, this conventionally balanced pool of news could lead to overstating the effectiveness of interventions, inducing skepticism, and understating the benefits of those intended to foster trust. In one notable study25, scholars re-adjusted the effect of their media literacy treatment to reflect the real-world prevalence of false news. However, they kept the proportion of false news constant and adjusted the proportion of false news post hoc. To estimate the causal effect of the proportion of news on such treatment effects, one needs to experimentally manipulate the proportion of false news.

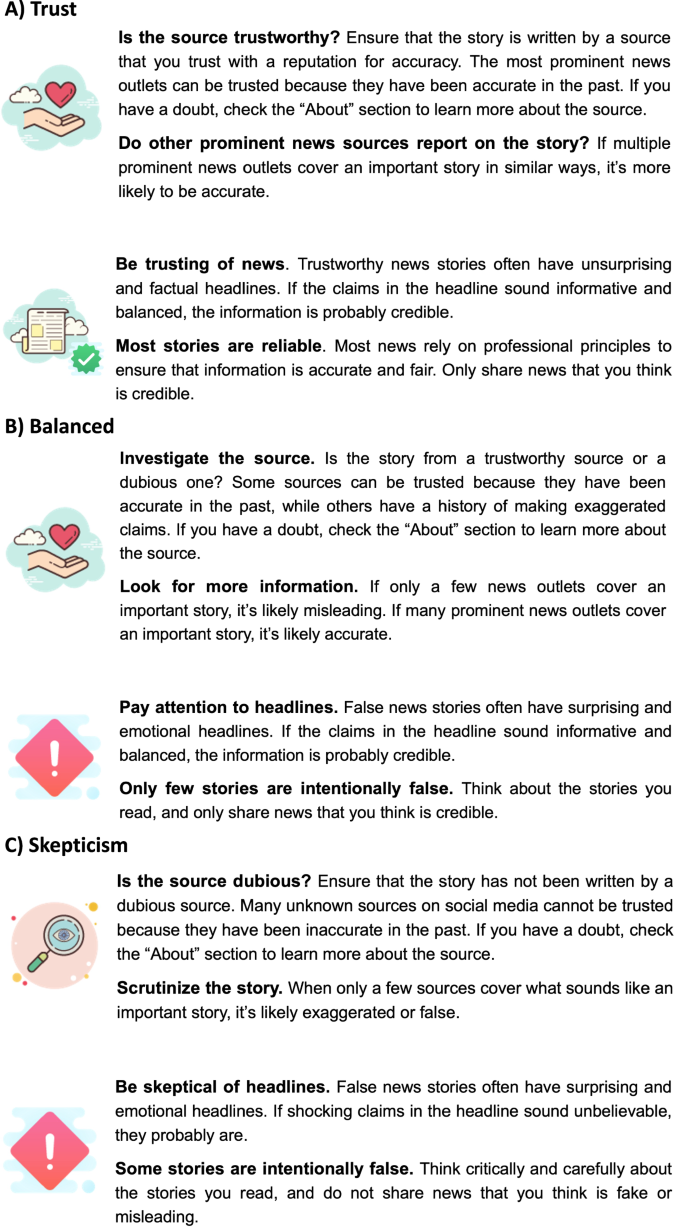

With these considerations in mind, we tested the effectiveness of three approaches to news media literacy interventions on a balanced sample in terms of gender and political orientation in the United States via Prolific (N = 3919). Respondents were randomly assigned to one of three media literacy conditions or a control group (with no tips). Participants were asked to either rate the accuracy of headlines or to report their willingness to share the headlines (between participants). We also measured several variables pre- and post-treatment such as trust in the news or interest in political news, to capture potential unintended treatment effects. The Skepticism Condition (N = 983) relies on the most common tips that aim to enhance skepticism (such as ”Be skeptical of headlines”). The Trust Condition (N = 973) relies on trust-enhancing tips emphasizing the prevalence of trustworthy (online) news (such as ”Be trusting of news”). Finally, the Mixed Condition (N = 967) relies on a mix of the above-mentioned skepticism- and trust-enhancing tips. Figure 1 provides a clear overview of what each intervention looked like.

Unlike past research designs testing the effectiveness of interventions against misinformation without including true news items11 or using unrealistic proportions of true and false news (50/50)9, we experimentally manipulated the proportion of true and false news participants were exposed to. Participants were either exposed to 75% of true news (and 25% of false news), 50% of true news, or 25% of true news. Given the interest of policymakers and platforms to implement these interventions, it is crucial to address this potential methodological problem and test these interventions on realistic proportions of true and false news.

We preregistered six hypotheses regarding the effects of media literacy strategies on the perceived accuracy of headlines and participants’ willingness to share them. First, we expected that all tips would be effective at improving discernment between true and false news (H1). Second, we predicted that the Skepticism-enhancing tips would lead to a more cautious assessment of news headlines, lowering the overall ratings of both true and false headlines (H2a). Conversely, we predicted that the Trust-inducing tips would result in more favorable evaluations across the news spectrum, increasing the overall ratings of both true and false headlines (H2b). Note that H1 and H2 are not incompatible. For instance, a treatment can increase discernment by increasing the sharing of both true and false news, as long as the effect on true news is significantly stronger. We also tested whether the proportion of false news participants were exposed to would influence the effectiveness of the tips. We predicted that the skepticism-enhancing tips would be most effective with a higher proportion of false news (75% compared to 25%; H3a), and that the trust-enhancing tips would be most effective with a lower proportion of false news (25% compared to 75%). Finally, we predicted that the skepticism-enhancing tips would decrease interest in the news (H4a), trust in the news (H5a), and trust in untrustworthy news outlets (H6a). Conversely, we predicted that the trust-enhancing tips would increase interest in the news (H4b), trust in the news (H5b), and trust in trustworthy news outlets (H6b).

Methods

Participants

Between the 22nd of August 2023 and the 31st of August 2023, we recruited 3919 participants in the US via Prolific and excluded five participants who failed the attention check (1944 women and 1970 men; 1330 Independents, 1278 Republicans, 1306 Democrats; Mage = 42.18, SDage = 13.82). The sample was balanced in terms of gender and political orientation. Participants were paid $1.12 ($11.19/h) to complete the study (for a median completion time of 6 min).

Design and procedure

After the consent form, participants reported the extent to which they are interested in political news “How interested are you in political news?”(from “Not at all interested” [1] to “Extremely interested” [5]). Then, participants were asked “Generally speaking, to what extent do you trust news sites such as” (on a 7-point Likert scale from [1] Not at all to [7] Completely, with “Neither trust nor distrust” as the middle point [4], and “I don’t know any of them” as the last option) and reported the extent to which they trust four groups of news outlets: (i) CNN, The New York Times, MSNBC, (ii) Fox News, The Wall Street Journal, New York Post, (iii) Occupy Democrats, Daily Kos, Palmer Report, (iv) Breitbart, The Gateway Pundit, The Daily Caller. We consider the first group as “mainstream left-leaning”, the second as “mainstream right-leaning”, the third as “generally untrustworthy left-leaning” and the fourth as “generally untrustworthy right-leaning”. Next, participants were asked, “To what extent do you trust the following institutions/groups?” (on a 7-point Likert scale from [1] Not at all to [7] Completely, with “Neither trust nor distrust” as the middle point [4]) and reported the extent to which they trust (i) traditional media, (ii) social media, (iii) journalists, and (iv) scientists.

Participants reported how much time they spend on social on a typical day (“On a typical day, how much time do you spend on social media (such as Facebook and Twitter; either on a mobile or a computer)?” from “Less than 30 min” [1] to “3+ hours” [5]). We measured self-reported media literacy (taken from38 by measuring agreement with the following four statements on a 7-point Likert scale (from “Strongly disagree” [1] to “Strongly agree” [7], with “Neither agree nor disagree” as the middle point [4]): “I have the skills to interpret media messages”, “I understand how news is made in the U.S.”, “I am confident in my ability to judge the quality of news”, and “I’m often confused about the quality of news and information” (reverse coded). Participants completed an attention check requiring them to read instructions hidden in a paragraph and write “I pay attention”. All the questions, including the Qualtrics files necessary to replicate the survey, are publicly available on OSF: https://osf.io/73y6c/. We also report the full survey questions in Supplementary Information F.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: (i) the Trust Condition (N = 963), where they received media literacy tips aimed at enhancing trust, (ii) the Skepticism Condition (N = 983), where tips were designed to enhance skepticism, (iii) the Mixed Condition (N = 967), which involved a combination of trust- and skepticism-enhancing tips, and (iv) the Control Condition, where no tips were provided. Prior to the study, we pre-tested the tips to ensure they conveyed the intended properties effectively. Tips in the Trust Condition were rated as more positive and trust-enhancing than those in the Balanced Condition, which, in turn, were seen as more positive and trust-enhancing than those in the Skepticism Condition. All tips were evaluated as easy to read, informative, and moderately convincing.

We also manipulated the dependent variable, prompting half of the participants to rate the accuracy of the headlines (“To the best of your knowledge, how accurate is the claim in the above headline?” from “Certainly False” [1] to “Certainly True” [6]) while the other half reported how willing they would be to share the headlines (“If you were to see this post online, how likely would you be to share it online?” from “Extremely unlikely” [1] to “Extremely likely” [6]).

In addition, we manipulated the proportion of true-to-false news to which participants were exposed. One-third of participants assessed eight true and four false news (75% true news), another third evaluated six true and six false news (50% true news), and the final third ratied four true and eight false news (25% true news). Our experimental design encompassed four media literacy conditions, two response types (sharing or accuracy), and three proportions of news veracity (i.e., 4 × 2 × 3). All participants viewed 12 political headlines formatted as they would appear on Facebook—a headline with an image and a source. We selected these political news headlines from a pre-tested pool of 40, ensuring a balance of perceived accuracy, sharing intentions, and strength of partisanship across Democrats and Republicans. The true headlines were found on mainstream US news outlets, while false headlines were found on fact-checking websites such as PolitiFact and Snopes.

After rating the headlines, participants assessed their performance in the study relative to other Americans, ranging from “worse than 99% of people” [1] to “better than 99% of people” [100]39. We calculated overconfidence by subtracting participants’ actual performance from their estimated performance, with higher scores indicating greater overconfidence. Then, participants reported their interest in political news, trust in news, and trust in specific US news outlets again. Information about political orientation (self-identification as an Independent, Democrat, or Republican), gender, and age were retrieved via Prolific. At the end of the survey, participants were debriefed about the purpose of the study and warned about their exposure to false news. The study received ethical approval from the University of Zürich PhF Ethics Committee (ethics approval nr. 23.04.17).

Statistical analyses

We use an alpha threshold of 5% for statistical significance. To estimate treatment effects on accuracy and sharing ratings, we analyzed the data at the response level (N observations = 46,992) using linear mixed-effects models with random effects for participants and news headlines. The effect on attitudes was analyzed at the participant level and tested with OLS linear regressions. In all models, we control for age, gender, and political orientation, as well as for the proportion of true news, the type of dependent variable (sharing or accuracy), and the experimental condition.

Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. As a robustness check, we ran a poisson generalized linear mixed model (robust to violations of normality) to test H1 and replicated the results of the linear mixed-effects models (see Table 17 in Supplementary Information E). All variables measured with Likert scales were treated as continuous. Age and education were treated as continuous as well, whereas Condition, Veracity, and political orientation were treated as categorical.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

What is the effect of the media literacy interventions on discernment (H1)?

We investigate individuals’ capacity for discernment, defined as the difference between the ratings of true versus false news, across the Trust, Skepticism, and Mixed conditions compared to the Control group. Supporting H1, we found that general discernment, combining both accuracy and sharing metrics, was significantly higher in the Mixed Condition (b = 0.23[0.17, 0.29], p < 0.01), Trust Condition (b = 0.22[0.16, 0.29], p < 0.01) and Skepticism Condition (b = 0.19[0.13, 0.25], p < 0.001).

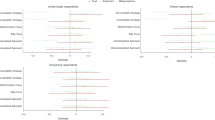

Significant effects were observed for both accuracy ratings and sharing ratings. As shown in Fig. 2, sharing discernment was greater in the Mixed Condition (b = 0.17[0.09, 0.24], p < 0.001), Trust Condition (b = 0.24[0.16, 0.32], p < 0.001) and Skepticism Condition (b = 0.17[0.09, 0.24], p < 0.001) compared to the Control Condition. Similarly, accuracy discernment was also significantly larger in the Mixed Condition (b = 0.22[0.14, 0.30], p < 0.001), Trust Condition (b = 0.12[0.04, 0.21], p < 0.001) and Skepticism Condition (b = 0.18[0.10, 0.26], p < 0.001).

Estimated differences in accuracy (blue triangles) and sharing (red circles) discernment in each experimental condition compared to the Control Condition. The error bars represent the 95% CIs. In the Control Accuracy N = 477. In the Sharing Accuracy N = 505. In the Mixed Accuracy N = 494. In the Mixed Sharing N = 472. In the Skepticism Accuracy N = 487. In the Skepticism Sharing N = 496. In the Trust Accuracy N = 495. In the Trust Sharing N = 478.

We observed no statistically significant differences between treatments regarding general discernment (see Tables 11 and 12 in Supplementary Information E). The only statistically significant difference observed between conditions is that the Trust Condition was less effective at increasing accuracy discernment compared to the Mixed Condition (b = −0.09[−0.17, −0.01], p = 0.025). Note that sharing discernment is slightly higher in the Trust Condition compared to the Mixed Condition (b = 0.07[−0.00, 0.15], p = 0.068) but this difference is not statistically significant.

What is the effect of the media literacy interventions on true and false news ratings (H2)?

We hypothesized distinct outcomes for the Skepticism and Trust Conditions. Specifically, we hypothesized that participants in the Skepticism Condition would be less likely to rate news stories as accurate and to share them, compared to those in the Control Condition (H2a). Conversely, we anticipated that participants in the Trust Condition would be more likely to perceive news as accurate and to share it, relative to the Control Condition (H2b).

Our results, displayed in Fig. 3, provide partial support for H2. In the Trust Condition, we observed a significant increase in the ratings of true news (b = 0.12[0.04, 0.21], p = 0.004); however, the effect on false news was not significant (b = −0.04[−0.11, 0.03], p = 0.27). Similarly, the Skepticism Condition significantly reduced the ratings of false news (b = −0.10[−0.16, −0.027], p =0.006), but did not significantly affect true news ratings (b = 0.067[−0.02, 0.15], p = 0.11). Remarkably, the Mixed Condition achieved both objectives: it significantly increased the ratings for true news (b = 0.10[0.02, 0.19], p = 0.018) and reduced the ratings for false news (b = −0.07[−0.14, −0.01], p = 0.034). Furthermore, the results show that the efficacy of media literacy interventions is contingent upon their focus: the Trust Condition predominantly bolsters the rating of true news, the Skepticism mainly reduces the rating of false news, while the Mixed Condition does a bit of both.

Estimated difference in true (red circles) and false (blue triangles) news ratings in each experimental condition compared to the Control Condition. The error bars represent the 95% CIs. The number of participants are the same for true and false news. In the Control Condition N = 982. In the Mixed Condition N = 967. In the Skepticism Condition N = 983. In the Skepticism Condition N = 973.

Note however that while the treatments significantly differ from the control, exploratory post-hoc analyses show the effects of the treatments are not statistically different from one another (see Tables 8–11 in Supplementary Information for all possible contrasts between conditions). For instance, the effect of the Trust Condition on true news is not statistically different from the effect of the Skepticism Condition on true news. Likewise, the effect of the Skepticism Condition on false news is not statistically different from the effect of the Trust Condition on false news.

Is the effect of the media literacy tips moderated by the proportion of true news (H3)?

We hypothesized that the Skepticism Condition would be most effective with a high proportion of false news (H3a), while the Trust Condition would be most effective with a low proportion of false news (H3b). To test H3, we ran a three-way interaction between the assigned condition, the news veracity, and the assigned proportion of true news, such that the effect of the condition is compared to baseline levels in the Control Condition.

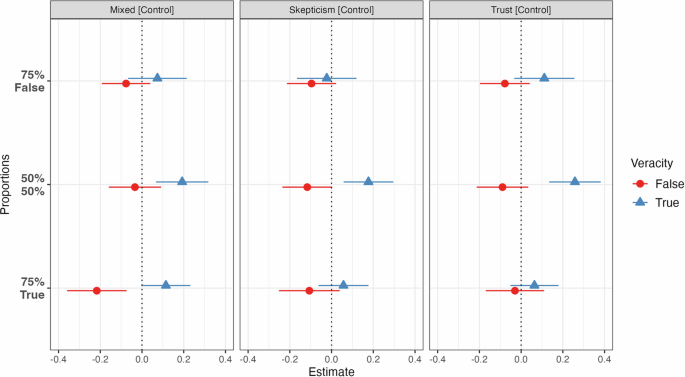

In Fig. 4, we can see that our findings contradict these expectations: in contrast with H3b, the Trust Condition and the Skepticism Condition were mostly effective at increasing discernment when participants were exposed to 50% of false news and 50% of true news—mostly because of an increase in true news ratings. The Mixed Condition was most effective when participants were exposed to 75% of true news and 25% of false news—mostly because of a reduction in false news ratings.

Estimated differences in true (red circles) and false (blue triangles) news ratings in each treatment condition compared to the control. The estimates are divided by the proportion of true and false news participants were exposed to. For instance, in the “75% False” participants were exposed to 75% of false news. The error bars represent the 95% CIs. In the Control 75% False N = 318. In the Control 50/50 N = 344. In the Control 75% True N = 320. In the Mixed 75% False N = 346. In the Mixed 50/50 N = 295. In the Mixed 75% True N = 326. In the Skepticism 75% False N = 325. In the Skepticism 50/50 N = 357. In the Skepticism 75% True N = 301. In the Trust, 75% False N = 311. In the Trust 50/50 N = 310. In the Trust 75% True N = 352.

The three-way interactions showed that (compared to the Control) the Trust Condition was most effective at increasing discernment when participants were exposed to 50% of true news compared to 75% of true news (b = 0.25[0.11, 0.40]; p = 0.001). The Mixed Condition was most effective at increasing discernment when participants were exposed to 75% of true news compared to 25% of true news (b = 0.18[0.021, 0.34]; p = 0.027). All the other contrasts are not statistically significant (see Table 4 in Supplementary Information E). Note, however, that we lack the statistical power to reliably detect small effects in such three-way interactions (despite our analysis of the data at the response level of 46,992 ratings).

What is the effect of the media literacy tips on interest and trust in the news? (H4–6)

We formulated several hypotheses regarding the effect of media literacy tips on interest in the news, trust in traditional media and journalists, and trust in specific news outlets. The data did not support our hypotheses. Compared to the Control Condition, the media literacy tips had no statistically significant effects on interest in the news, trust in traditional media and journalists, or trust in specific (right- or left-wing) news outlets (see Tables 4–6 in Supplementary Information E). The only statistically significant effect (partially supporting H5b) is that the Trust Condition increased trust in traditional media compared to the Control Condition (b = 0.08[0.02, 0.14]; p = 0.008). This increase in trust in the Trust Condition is also significantly different when compared to the Skepticism Condition (b = 0.092[0.03, 0.15]; p = 0.003) as well as the Mixed Condition (b = 0.076[0.02, 0.14]; p = 0.014).

What is the effect of the media literacy tips on confidence and overconfidence? (preregistered exploratory analyses)

Here we investigate the effect of the media literacy tips and the proportion of false news on people’s confidence in their ability to discern true from false news. These analyses are restricted to accuracy ratings given that the confidence question is about ”recognizing news that is made up”.

We found that, compared to the Control Condition, the media literacy tips tended to increase participants’ confidence in their ability to discern true from false news while reducing overconfidence, but these effects were small and inconsistent across conditions. Second, the more false news participants were exposed to, the more confident they were in their ability to recognize made-up news, but this increase in confidence did not translate into more or less overconfidence—these effects were consistent across conditions (see Supplementary Information A).

Heterogeneous treatment effects (preregistered exploratory analyses)

We found that the Skepticism Condition was much more effective than the other conditions at increasing discernment among Independents compared to the Control Condition (b = 0.34[0.19, 0.48], p < 0.001). The Mixed Condition was more effective at increasing discernment among men than women (b = 0.15[0.03, 0.28], p = 0.014), while the Skepticism Condition was more effective among women than men (b = 0.13[0.01, 0.25], p = 0.042). We also found that the Mixed Condition and the Skepticism Condition were slightly less effective at increasing discernment among more frequent social media users (b = − 0.06[−0.11, −0.01], p = 0.02). Finally, we found no statistically significant heterogeneous treatment effects of media literacy (Trust: b = 0.02 [−0.04, 0.09], p = 0.46; Mixed: b = 0.04 [−0.02, 0.10], p = 0.22; Skepticism: b = 0.02 [−0.04, 0.08], p = 0.47), age (Trust: b = −0.001 [−0.01, 0.001], p = 0.58; Mixed: b = −0.001 [−0.01, 0.001], p = 0.23; Skepticism: b = 0.001 [−0.01, 0.01], p = 0.84), interest in news (pre-treatment) (Trust: b = 0.001 [−0.06, 0.07], p = 0.88; Mixed: b = 0.001 [−0.06, 0.07], p = 0.91; Skepticism: b = −0.063 [−0.13, −0.001], p = 0.050), trust in social media (pre-treatment) (Trust: b = −0.02 [−0.06, 0.03], p = 0.46; Mixed: b = −0.001 [−0.05, 0.04], p = 0.95; Skepticism: b = 0.02 [−0.02, 0.07], p = 0.29). In Supplementary Information B, we offer a visual representation of statistically significant effects.

Determinants of discernment (exploratory analysis)

We ran an OLS regression to estimate the effect of socio-demographic variables while controlling for the effect of Conditions and the proportion of false news participants were exposed to. We found that interest in political news (b = 0.14[0.09, 0.19], p < 0.001), self-reported media literacy (b = 0.10[0.05, 0.15], p < 0.001), being older (b = 0.004[0.001, 0.007], p = 0.031), being a woman (b = 0.10[0.01, 0.18], p = 0.032), and identifying as Democrat rather than Independent (b = 0.11[0.01, 0.22], p = 0.040) was associated with greater discernment. Identifying as Republican (b =− 0.07[−0.18, −0.04], p = 0.214), trust in the news (b = 0.016[−0.013, 0.045], p = 0.272), and social media use (b = − 0.03[−0.061, 0.009], p = 0.142), were not significantly associated with discernment (see Fig. 3 in Supplementary Information C).

Discussion

Our pre-registered survey experiment shows that all the tips increased participants’ ability to discern between true and false news headlines, both in terms of sharing intentions and perceived accuracy. The Trust Condition significantly increased ratings of true news (but not false news), the Skepticism Condition significantly decreased ratings of false news (but not true news), while the Mixed Condition did both. Yet, the effects of the tips were much more alike than different, with very similar effect sizes across conditions for true and false news. The media literacy tips had null effects on interest in the news and trust in the news—the only exception being that the Trust Condition increased trust in traditional media.

These findings are insightful for social media platforms and other entities keen on enhancing the quality of the information ecosystem. While most existing media literacy tips resemble our Skepticism Condition and specifically target misinformation25,40, we show that improving discernment does not require focusing on misinformation. Discernment can also be improved by targeting reliable information (Trust Condition) or by emphasizing both skepticism toward misinformation and trust in reliable information (Mixed Condition). Future media literacy interventions should consider both sides of the equation. Yet, one should keep in mind that there is no quick fix, and the effectiveness of the tips should be seen as a complement to, not a substitute for, longer interventions and more ambitious systemic solutions.

The weight given to either combating misinformation or promoting reliable information should be context-dependent. For instance, in high-quality information environments, where misinformation is relatively rare but where trust in the news is sometimes low, it may be more fruitful to foster reliable information. In contrast, in lower-quality information environments where misinformation is rampant such as in some emerging democracies or autocracies, the emphasis should be on cultivating a healthy skepticism. More granular targeting is also possible. For instance, “Trust tips” could be featured as ads on trustworthy news websites or alongside their social media posts to boost acceptance of their content. Conversely, “Skepticism Tips” could be targeted at untrustworthy news websites or alongside their social media posts to encourage rejection of their content. Trust tips may be effective even if misinformation is not very prevalent and impactful, as long as there is some room to increase the acceptance of reliable information9,16. Yet, our experimental findings do not support the idea that trust tips are more effective in an environment with more true news, and vice versa. More testing is necessary to know what kind of tips may be more or less effective in different kinds of environments.

In Western democracies, the importance of promoting reliable information is all the more pressing in light of low levels of trust in the news, low levels of political interest, and the growing number of people who avoid the news and are left largely uninformed about political matters and current events7. Literacy efforts should adapt to this reality and reconsider the importance of promoting reliable information. Otherwise, these efforts risk fueling people’s cynicism toward the news even more41.

Given the discrepancy between the high prevalence of false news in experiments testing the effectiveness of interventions against misinformation9, and the low prevalence of false news outside of experimental settings3,4,5, we experimentally manipulated the proportion of true and false news participants were exposed to. We found that the proportion of true and false news matters—though not in the way we expected. The Trust and Skepticism Conditions were most effective when participants were exposed to equal proportions of true and false news, while the Mixed Condition was most effective when participants were exposed to 75% of true news—a proportion most reflective of the ecological base rates of true news in Western democracies. Yet, we lack the statistical power to detect very small effects. Thus, before implementing the tips in the wild, our findings should be replicated on a larger sample size and across more diverse populations.

In contrast with recent work1, our findings do not support the idea that media literacy tips, even when skepticism-enhancing, have unintended consequences on true news or on trust in the news. More work is needed to precisely estimate the robustness and size of these effects, both for media literacy tips and interventions against misinformation more broadly.

In line with past work showing that the 50/50 ratio does not influence news discernment42, our findings do not imply that studies relying on a 50/50 ratio are flawed or that the use of this ratio is wrong. Instead, future research should strive to find the optimal balance between statistical power and ecological validity, while concurrently avoiding survey fatigue and excessive exposure to headlines. A 50/50 ratio is the sweet spot to maximize statistical power, while 75% of true news and 25% of true news is more ecologically valid. We recommend that interventions intended for real-world application should be tested not just in conditions that maximize statistical power, but also in conditions that heighten ecological validity to accurately gauge the impact of these interventions outside of experimental settings. Given the predominant focus on practical implications in much of the literature on interventions against misinformation, future studies should evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in conditions that more closely mimic the real world (e.g., by using more realistic proportions of true news and false news, or by including non-news items, which represent the vast majority of people’s social media feeds).

Limitations

An important limitation of the present work is that we did not investigate the precise mechanisms through which the media literacy tips improved discernment. One possible explanation is that the tips primarily prompted participants to think about accuracy15. However, this account falls short in predicting the specificity of our treatment effects: the Trust-inducing tips selectively enhanced belief in true news, while Skepticism-centered tips uniquely reduced belief in false news. Another possible explanation is that participants genuinely learned from the tips and that this new knowledge helped them better discern true from false news. Given the short length of the tips and past research showing that the effects of such tips and one-shot interventions are ephemeral25,43, we are skeptical of this explanation. The most plausible explanation, in our view, is that the tips primed trust or skepticism. When told that there was a lot of false news and that they should be vigilant, participants temporarily adopted a more skeptical mindset, expected to be exposed to more false news, and looked for signs of deception. Whereas when told that most news is reliable and that they should be trusting, participants temporarily adopted a more trusting mindset, expected to be exposed to more true news, and looked for signs of reliability. This explanation accounts for the specificity of the treatment effects (such as the increase in news trust in the Trust Condition) and is in line with past work showing that skepticism-inducing interventions against misinformation reduce the acceptance of true news1,2,31. However, this explanation predicts that the trust-inducing tips should be more effective in the 75% true news environment, while the skepticism-inducing tips should work be more effective in the 25% true news environment, and this is not what we find. Future work should experimentally investigate the mechanisms that make such tips effective. One way to do so is to ‘unbundle’ tips and look at the causal effect of each specific tip in isolation. For instance44, found that broad tips (e.g., “Be skeptical of headlines”) are less effective than narrow tips (e.g., “Look closely at the website domain”), and that tips may only work “insofar as they provide specific information that is diagnostic of quality” (p. 15). They found that tips drawing people’s attention to the source of the posts were the most effective. In our case, all tips draw attention to the source, so it cannot explain the differences between treatments, but it is possible that the tips drew attention to other specific elements of the headlines that helped participants discern between true and false news.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings underline the value of media literacy tips in increasing citizens’ ability to discern truth from falsehoods. We also show that to increase discernment, such tips do not need to focus exclusively on inducing skepticism in misinformation but can also promote trust in reliable information. We encourage organizations and social media platforms that rely on such tips to stop using tips that exclusively induce skepticism—especially given the low prevalence of misinformation in Western democracies. Instead, they should aim at both inducing skepticism in misinformation and promoting trust in reliable information.

Data availability

The replication data, including all (stimulus) materials used in this study, is available at https://osf.io/73y6c/.

Code availability

The replication code is available at https://osf.io/73y6c/.

References

Hoes, E., Aitken, B., Zhang, J., Gackowski, T. & Wojcieszak, M. Prominent misinformation interventions reduce misperceptions but increase scepticism. Nat. Hum. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01884-x (2024).

Hameleers, M. The (un) intended consequences of emphasizing the threats of mis-and disinformation. Media Commun. 11, 5–14 (2023).

Allen, J., Howland, B., Mobius, M., Rothschild, D. & Watts, D. Evaluating the fake news problem at the scale of the information ecosystem. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay3539 (2020).

Guess, A., Nagler, J. & Tucker, J. Less than you think: prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau4586 (2019).

Altay, S., Nielsen, R. K. & Fletcher, R. Quantifying the “infodemic”: people turned to trustworthy news outlets during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. J. Quant. Descr. 2, 1–29 (2022).

Acerbi, A., Altay, S. & Mercier, H. Research note: fighting misinformation or fighting for information? HKS Misinf. Rev. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-87 (2022).

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C. T. & Nielsen, R. K. Digit. News Rep. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2023 (2023).

Nielsen, R. K., Palmer, R. & Toff, B. Avoiding the News: Reluctant Audiences for Journalism (Columbia University Press, 2023).

Pfänder, J. & Altay, S. Spotting false news and doubting true news: a meta-analysis of news judgements. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://osf.io/n9h4y/ (2023).

Mihailidis, P. Beyond Cynicism: How Media Literacy Can Make Students More Engaged Citizens (University of Maryland, College Park, 2008).

Guay, B., Berinsky, A. J., Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. How to think about whether misinformation interventions work. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1231–1233 (2023).

Vraga, E. K., Tully, M. & Rojas, H. Media literacy training reduces perception of bias. Newsp. Res. J. 30, 68–81 (2009).

Byrne, S. Media literacy interventions: what makes them boom or boomerang? Commun. Educ. 58, 1–14 (2009).

van der Meer, T. G. & Hameleers, M. Fighting biased news diets: using news media literacy interventions to stimulate online cross-cutting media exposure patterns. N. Media Soc. 23, 3156–3178 (2021).

Pennycook, G. et al. Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature 592, 590–595 (2021).

Altay, S. How effective are interventions against misinformation? PsyArXiv https://osf.io/sm3vk/ (2022).

Aslett, K., Guess, A., Bonneau, R., Nagler, J. & Tucker, J. A. News credibility labels have limited average effects on news diet quality and fail to reduce misperceptions. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl3844 (2022).

Bulger, M. & Davison, P. The promises, challenges, and futures of media literacy. Data Soc. 10, 1–21 (2018).

Wardle, C. & Derakhshan, H. Information disorder: toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Counc. Eur. Rep. 27. https://edoc.coe.int/en/media/7495-information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-research-and-policy-making.html (2017).

Vraga, E., Tully, M., Maksl, A., Craft, S. & Ashley, S. Theorizing news literacy behaviors. Commun. Theory 31, 1–21 (2021).

Martel, C., Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. G. Reliance on emotion promotes belief in fake news. Cogn. Res. 5, 47 (2020).

Harsin, J. Post-truth and critical communication studies. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Commun. (2018).

Abramowitz, M. J. Stop the manipulation of democracy online. N. Y. 11, 2017 (2017).

Qian, S., Shen, C. & Zhang, J. Fighting cheapfakes: using a digital media literacy intervention to motivate reverse search of out-of-context visual misinformation. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 28, zmac024 (2023).

Guess, A. et al. A digital media literacy intervention increases discernment between mainstream and false news in the United States and India. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 15536–15545 (2020).

van der Meer, T. G., Hameleers, M. & Ohme, J. Can fighting misinformation have a negative spillover effect? How warnings for the threat of misinformation can decrease general news credibility. J. Stud. 24, 803–823 (2023).

Lyons, B., King, A. J. & Kaphingst, K. A health media literacy intervention increases skepticism of both inaccurate and accurate cancer news among US adults. OSF Preprint https://osf.io/hm9ty/ (2024).

Van Duyn, E. & Collier, J. Priming and fake news: the effects of elite discourse on evaluations of news media. Mass Commun. Soc. 22, 29–48 (2019).

Tandoc, E. C. et al. Audiences’ acts of authentication in the age of fake news: a conceptual framework. N. Media Soc. 20, 2745–2763 (2018).

Vraga, E., Tully, M. & Bode, L. Assessing the relative merits of news literacy and corrections in responding to misinformation on Twitter. N. Media Soc. 24, 2354–2371 (2022).

Modirrousta-Galian, A. & Higham, P. A. Gamified inoculation interventions do not improve discrimination between true and fake news: reanalyzing existing research with receiver operating characteristic analysis. J. Exp. Psychol. 152, 2411–2437 (2023).

Hoes, E., Clemm von Hohenberg, B., Gessler, T., Wojcieszak, M. & Qian, S. Elusive effects of misinformation and the media’s attention to it: evidence from experimental and behavioral trace data. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/4m92p (2022).

Vraga, E. K. & Tully, M. News literacy, social media behaviors, and skepticism toward information on social media. Inf. Commun. Soc. 24, 150–166 (2021).

Craft, S., Ashley, S. & Maksl, A. News media literacy and conspiracy theory endorsement. Commun. Public 2, 388–401 (2017).

Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B. & Lazer, D. Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 us presidential election. Science 363, 374–378 (2019).

Osmundsen, M., Bor, A., Vahlstrup, P. B., Bechmann, A. & Petersen, M. B. Partisan polarization is the primary psychological motivation behind political fake news sharing on twitter. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 115, 999–1015 (2021).

Boberg, S., Quandt, T., Schatto-Eckrodt, T. & Frischlich, L. Pandemic populism: Facebook pages of alternative news media and the Corona crisis—a computational content analysis. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2004.02566 (2020).

Vraga, E., Tully, M., Kotcher, J. E., Smithson, A.-B. & Broeckelman-Post, M. A multi-dimensional approach to measuring news media literacy. J. Media Lit. Educ. 7, 41–53 (2015).

Lyons, B. A., Montgomery, J. M., Guess, A. M., Nyhan, B. & Reifler, J. Overconfidence in news judgments is associated with false news susceptibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2019527118 (2021).

Clayton, K. et al. Real solutions for fake news? Measuring the effectiveness of general warnings and fact-check tags in reducing belief in false stories on social media. Polit. Behav. 42, 1073–1095 (2020).

Boyd, D. Did media literacy backfire? J. Appl. Youth Stud. 1, 83–89 (2017).

Altay, S., Lyons, B. & Modirrousta-Galian, A. Exposure to higher rates of false news erodes media trust and fuels overconfidence. Mass Commun. Soc. (2024).

Maertens, R., Roozenbeek, J., Basol, M. & van der Linden, S. Long-term effectiveness of inoculation against misinformation: three longitudinal experiments. J. Exp. Psychol. 27, 1 (2021).

Guess, A., McGregor, S., Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. Unbundling digital media literacy tips: results from two experiments. OSF, https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/u34fp (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Fabio Mellinger and Sophie van IJzendoorn for excellent research assistance. Funding: This project received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement nr. 883121) and the Swiss National Science Foundation under Grant (grant agreement nr PZ00P1 201817). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Research Council or the Swiss National Science Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S.A., A.A., and E.H. Analyses: S.A. and A.A. Investigation: S.A, A.A., E.H. Visualization: S.A., A.A. Writing—original draft: S.A., A.A., and E.H. Writing—review & editing: S.A., A.A., and E.H.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. For transparency, we report that in 2021 E.H. received an unrelated, unrestricted research grant ($50k) from Meta. Meta did not contribute in any way to this study.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Psychology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jennifer Bellingtier. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Altay, S., De Angelis, A. & Hoes, E. Media literacy tips promoting reliable news improve discernment and enhance trust in traditional media. Commun Psychol 2, 74 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-024-00121-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-024-00121-5

- Springer Nature Limited