Abstract

Background

Recent work has explored the sociocultural aspects of pain. However, global evidence is scarce, and little is known about how levels of pain differ across cultures and across demographic groups within those different cultures.

Methods

Using a nationally representative dataset of 202,898 individuals from 22 countries and a random effects meta-analysis, we examine the proportion of people in pain across key demographic groups (age, gender, marital status, employment status, education, immigration status, religious service attendance, race/ethnicity) and across countries.

Results

We find substantial variation in pain across countries and demographic groups. Unadjusted proportions tests show that Egypt (0.60), Brazil (0.59), Australia (0.56), and Turkey (0.53) have the greatest proportion of people in pain whereas Israel (0.25), South Africa (0.29), Poland (0.32), and Japan (0.33) have the lowest proportion. The random effects meta-analysis shows that, across countries, the proportion of people in pain is highest in older age groups, among women and other gender groups, the widowed, those who were retired, those who had low level of education, and those who attended a religious service more than once a week. The analysis shows no difference in the proportion of people in pain regarding immigration status.

Conclusions

Pain varies substantially across countries and key demographic groups. This work provides valuable foundational insights for future research on the sociocultural factors of pain.

Plain language summary

Understanding how the proportion of people in pain varies across key demographic groups and across countries is of high importance. Here, we used rigorous statistical techniques to uncover how pain varies across demographic groups and across 22 countries from all over the world. We found that the proportion of people in pain is highest in older age groups, among women and other gender groups, the widowed, those who were retired, those who had low level of education, and those who attended a religious service more than once a week. Substantial country-specific variation was also found. These findings may serve as a starting point for future research on other social aspects of pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage’1. Pain is one of the most typical human feelings and it has shown a rising trend all over the world in the last decade2. In particular, 27.8% of people experienced some kind of pain in the United States in 20213 while 30% of medical consultations in the United Kingdom are related to musculoskeletal pain4. Pain prevalence is also high in other regions like Saharan Africa, the Arab countries, and Southern Asia5. Pain is a global problem.

Prior work has shown that pain also varies across demographic groups. For instance, using data from the United States, Case and Deaton6 have shown that white non-Hispanics aged 45–54 reported greater pain than other race and age groups. In a related study that also used US data, the same authors found that people with a bachelor degree reported lower pain than those who had not graduated from college7. Using data from older adults in the United States, Janevic and colleagues8 found that pain intensity was highest among individuals in the lowest wealth quartile while Kennedy et al.9 showed that pain was greater among women and people between 60 and 69 years of age 10. These patterns were also found in developed European nations. For instance, Zimmer et al.11 examined a sample of people over the age of 50 in 15 European countries and found that pain prevalence was highest among women and the elderly. Using data from 19 European countries, Todd et al.12 showed that pain prevalence was lower in Central and Eastern European countries like Hungary and Lithuania and greater in Western European countries like Germany and Finland. The authors also found general socioeconomic disparities in pain: women (vs men) and people with lower education (vs higher) reported greater pain. Religious attendance has also been found to be linked to pain: A longitudinal cohort study of Norwegian individuals has shown that individuals with a headache were more frequent religious attendees than those without a headache13.

Although pain prevalence across demographic groups has been previously explored, most existing evidence relied on data from the United States and developed European nations. Two exceptions used cross-national data from the Gallup World Poll (GWP) and showed differences in pain across continents and demographic groups. One study used data from 146 countries from the GWP and examined time trends in pain and how these time trends differed across demographic factors2. A follow-up study explored pain prevalence across continents and demographic groups during the COVID-19 pandemic5. In line with the evidence discussed earlier, these studies concluded that women (vs men), people with lower education and lower income levels (vs higher), the elderly (vs the younger and those in mid-life), the unemployed (vs the employed), and widowed and separated (vs single) individuals reported greater pain the day before. Other investigations on pain using the GWP but exploring different research questions include Case and Deaton7, Macchia and Oswald14, Macchia15, and Tang et al.16. Another exception is the study by Zimmer et al.17 that examined data from 52 countries and documented that pain was greater among women (vs men), older people (vs younger), and those living in rural areas (vs urban areas). The study also found that five country-level factors, namely region, population density, life expectancy, gender inequality, and income inequality, explained the cross-country variations of pain.

Although these studies used large and diverse datasets, they did not present cross-country distributions or cross-country meta-analyses and only examined a limited number of demographic factors leaving out other key aspects like religious service attendance, immigration status, and race/ethnicity. This body of work demonstrates that the literature on pain needs evidence on the foundational aspects of pain.

Here, we address this need by using a diverse dataset of 202,898 individuals from 22 countries to explore how levels of pain vary across cultures and several demographic groups within those different cultures. The present study examines three hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 suggests that the distributions and descriptive statistics of key demographic features (age, gender, marital status, employment, religious service attendance, education, immigration status, race/ethnicity) will reveal diverse patterns across our international sample from 22 countries. This hypothesis suggests that the distribution of pain across each demographic feature will vary across the 22 countries. Hypothesis 2 suggests that the proportion of people in pain will vary meaningfully across different countries. Hypothesis 3 proposes that pain will exhibit variations across different demographic categories such as age, gender, marital status, employment, education, and immigration status. These differences across demographic categories will themselves vary by country.

Overall, we find substantial variation in pain across countries and demographic groups. Specifically, across countries, the proportion of people in pain is highest in older age groups, among women and other gender groups, the widowed, those who are retired, those who have low level of education, and those who attend a religious service more than once a week. These findings offer insights into country-specific and demographic variations in pain and lays a valuable foundation for future research on the sociocultural factors that might shape pain.

Methods

The description of the methods below has been adapted from VanderWeele et al.18. Further methodological detail is available elsewhere19,20,21,22,23,24,25.

Data

The Global Flourishing Study (GFS) is a study of 202,898 participants from 22 geographically and culturally diverse countries, with nationally representative sampling within each country, concerning the distribution of determinants of wellbeing. Wave 1 of the data included the following countries and territories: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Egypt, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Tanzania, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The countries were selected to (a) maximize coverage of the world’s population, (b) ensure geographic, cultural, and religious diversity, and (c) prioritize feasibility and existing data collection infrastructure. Data collection was carried out by Gallup Inc. Data for Wave 1 were collected principally during 2023, with some countries beginning data collection in 2022 and exact dates varying by country23. Four additional waves of panel data on the participants will be collected annually from 2024-2027. The precise sampling design to ensure nationally representative samples varied by country and further details are available in Ritter et al.23.

Survey items included aspects of wellbeing such as happiness, health, meaning, character, relationships, and financial stability26, along with other demographic, social, economic, political, religious, personality, childhood, community, health, and wellbeing variables. The data are publicly available through the Center for Open Science (COS, https://www.cos.io/gfs). During the translation process, Gallup adhered to the TRAPD model (translation, review, adjudication, pretesting, and documentation) for cross-cultural survey research (ccsg.isr.umich.edu/chapters/translation/overview). Additional details about methodology and survey development can be found in the GFS Questionnaire Development Report19, and the GFS Methodology23, GFS Codebook, and GFS Translations documents20.

This project was ruled EXEMPT for Institutional Review Board (IRB) review by the Baylor University IRB (#1841317-2). Gallup Inc. IRB approved the study on November 16, 2021 (#2021-11-02). All data collection was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of Gallup and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained during the respondent recruitment stage of fieldwork. Consent was also obtained at the start of the survey. The exact wording varies across countries depending on the local laws and regulations governing data protection. All personally identifiable information (PII) was removed from the data used in this study by Gallup Inc.

Measures

Demographics variables

Continuous age was classified as 18–24, 25–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and 80 or older. Gender was assessed as male, female, or other. Marital status was assessed as single/never married, married, separated, divorced, widowed, and domestic partner. Employment was assessed as employed, self-employed, retired, student, homemaker, unemployed and searching, and other. Education was assessed as up to 8 years, 9–15 years, and 16+ years. Religious service attendance was assessed as more than once/week, once/week, one-to-three times/month, a few times/year, or never. Immigration status was dichotomously assessed with: “Were you born in this country, or not?” Religious tradition/affiliation with categories of Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Sikhism, Baha’i, Jainism, Shinto, Taoism, Confucianism, Primal/Animist/Folk religion, Spiritism, African-Derived, some other religion, or no religion/atheist/agnostic; precise response categories varied by country27. Racial/ethnic identity was assessed in some, but not all, countries, with response categories varying by country. For additional details on the assessments see the GFS codebook (https://www.cos.io/gfs) or Crabtree et al.19.

Outcome variable

Our pain measure comes from the following question: ‘How much bodily pain have you had during the past 4 weeks?’ Respondents could answer a lot, some, not very much, or none at all. To test the hypotheses about the proportion of people in pain, in our main analyses this variable was dichotomized as A lot/some (1) vs. not very much/none at all (0). We also conducted post-hoc sensitivity analysis with alternative dichotomization points including A lot (1) vs some/not very much/none at all (0) and A lot/some/not very much (1) vs none at all (0).

Sampling and data collection

In most countries, a probability-based face‑to-face or telephone methodology to recruit participants was implemented. To ensure representativeness of the population, we used different selection methods. For face-to-face interviews, the selection of probability-based samples was performed by selecting sampling units stratified by population size, urbanicity and/or geography, and clustering. For telephone interviews, the selection of participants was performed using random digit dialling or a nationally representative list of phone numbers. These various methods reduced the risk of excluding specific groups of the population, for example, those who did not have access to the internet. As part of the recruitment, participants first completed a survey about basic demographics and information for recontact. Then, participants received invitations to take part in the annual survey via phone or online. Eligibility for participation in the study required the selected participants to have access to a phone or the internet, a practical necessity to help retention. As a small token of appreciation for their time, eligible participants who completed the annual survey received a gift card or mobile top‑up worth roughly $5.

To recruit participants, three sampling frames were used: a probability-based sample, a non-probability-based sample, or a combination of both23. A probability-based sampling approach was used in Egypt, India, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Nigeria, Philippines, South Africa, Tanzania, Turkey, and the United States. To complement probability samples to obtain adequate coverage of population subgroups (i.e. sex, age, region), a non-probability-based sampling design was implemented in some countries. More details of the recruitment process, data collection stages, and sampling can be found in Padgett et al.25.

Statistics and reproducibility

Descriptive statistics for the full sample, weighted to be nationally representative within each country, were estimated for each of the demographic variables. Nationally representative proportions of people in pain were estimated separately for each country and ordered from highest to lowest along with 95% confidence intervals and standard deviations. Variation in proportions of people in pain across demographic categories were estimated, with all analyses initially conducted by country. Primary results consisted of random effects meta-analyses of country-specific proportions of people in pain in each specific demographic category28,29 along with 95% confidence intervals, standard errors, upper and lower limits of a 95% prediction interval across countries, heterogeneity (τ), and I2 for evidence concerning variation within a particular demographic variable across countries30. Meta-analyses were chosen because they are a rigorous and widely accepted method for synthesizing findings from multiple contexts. Forest plots of estimates are available in the Supplementary Information (SI). All meta-analyses were conducted in R31 using the metafor package32. Within each country, a global test of variation of outcome across levels of each particular demographic variable was conducted, and a pooled p-value33 (Global p-value) across countries reported concerning evidence for variation within any country. Bonferroni corrected p-value thresholds are provided based on the number of demographic variables34,35. Religious affiliation/tradition and race/ethnicity were used, when available, in the country-specific analyses, but were not included in the meta-analyses since the availability of these response categories varied by country. As a supplementary analysis, population-weighted meta-analyses were also conducted. All analyses were preregistered with COS prior to data access (https://osf.io/ewyr5/?view_only=1fceb9e7dac440a88ad1d5764a6ea6bd, see also Supplementary Note 1 in the Supplementary Information); all code to reproduce analyses are openly available in an online repository22.

Missing data

Missing data on all variables was imputed using multivariate imputation by chained equations, and five imputed datasets were used36,37,38,39. To account for variation in the assessment of certain variables across countries (e.g., religious affiliation/tradition and race/ethnicity), the imputation process was conducted separately in each country. This within-country imputation approach ensured that the imputation models accurately reflected country-specific contexts and assessment methods. Sampling weights were included in the imputation model to account for missingness to be related to probability of inclusion. We performed all analyses described above using each of the five imputed datasets and combined the results across the imputations via Rubin’s rule40.

Accounting for complex sampling design

The GFS used different sampling schemes across countries based on availability of existing panels and recruitment needs23. All analyses accounted for the complex survey design components by including weights, primary sampling units, and strata. Additional methodological detail, including accounting for the complex sampling design is provided elsewhere41.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the number and percentage of people across each demographic group in the observed sample: Most individuals were middle age (30–39 years old (20%), 40–49 years old (17%), 50–59 (16%)), most of the sample was composed of men and women (women (51%), men (49%)), most people were married (53%), employed for an employer (39%), and with 9 to 15 years of education (57%). Religious attendance was varied (never (37%), a few times a year (20%), once a week (19%)), and most people were born in the country in which the survey was conducted (94%). Table 1 also shows the number and percentage of people within each country: The countries with the greatest number of individuals were the United States (19%) and Japan (10%) whereas the countries with the lowest number of individuals were Turkey (0.7%) and South Africa (1.3%). Tables S1–S22 in the Supplementary Information show variation of the number and percentage of people in each demographic group in each of the 22 countries. These results confirm Hypothesis 1: The distributions of key demographic groups reveal diverse patterns across our international sample from 22 countries. This finding is itself relevant for interpreting country proportions.

Proportion of people in pain in each country

Getting into the outcome of interest of this study, Table 2 orders the countries based on the proportion of people in pain. As a reminder, our pain measure was dichotomized as A lot/some (1) vs. not very much/none at all (0). The countries with the greatest proportion of people in pain were Egypt (0.60), Brazil (0.59), Australia (0.56), and Turkey (0.53) whereas the countries with the lowest proportion of people in pain were Israel (0.25), South Africa (0.29), Poland (0.32), and Japan (0.33). In this case, standard deviations show the level of dispersion or inequality in pain across individuals in each specific country. The overall mean of the proportion of people in pain across the 22 countries is 0.44 (95%CI 0.40–0.48). We conducted post-hoc sensitivity analysis using different dichotomization points: a) A lot/some/not very much (1) vs none at all (0) and b) A lot (1) vs some/not very much/none at all (0). In both cases, the results are, in general, in line with the ones presented in the main analyses. One notable difference is that when combining the three categories that denote some pain into the same category (‘none at all’ coded as 0 and all the other categories coded as 1), Philippines moves to the top of the ranking together with Australia. The other notable difference is that when focusing on severe pain (‘a lot’ coded as 1 and all the other categories coded as 0), India moves to the top of the ranking together with Egypt, Turkey, and Brazil. All the other countries remain in the same quantile as in the original analyses. These results confirm Hypothesis 2: The proportion of people in pain vary meaningfully across different countries.

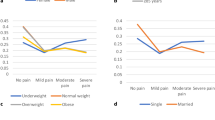

Meta-analytic proportions across countries

Table 3 shows the meta-analytic proportions for each demographic group across the 22 countries. This analysis shows that, across countries, the proportion of people in pain is highest in older age groups, among women and other gender groups, the widowed, those who were retired, who had low level of education, and those who attended a religious service more than once a week. This analysis also shows that the proportion of people in pain is the same among people who were born in the country in which the survey was conducted and those who were born in another country.

The ‘tau’ estimate measures how much the proportion of people in pain within a demographic category varies across countries. For instance, the gender category ‘Other’ (0.76) and the age category ‘80 or older’ (0.35) have higher ‘tau’ estimates than other categories. This indicates that the proportion of individuals in these categories varies more substantially across countries compared to the categories with smaller ‘tau’ estimates. The global p-value is highly significant in each demographic group indicating that the proportion of people in pain in a given demographic group differs statistically across countries. More details about the technical aspects of the global p-value can be found in Padgett et al.41.

Building on the heterogeneity estimate ‘tau’ shown in Table 3, Tables S23–S44 in the Supplementary Information allow us to examine the actual variation in the proportion of people in pain for each demographic group in each country separately. For instance, we found that the proportion of women (vs men) in pain is greater in all countries except for Hong Kong and Nigeria. These analyses also show that the proportion of people in pain is greater among the elderly in most countries except for Australia, Brazil, Egypt, and the United States which show high proportions of people in pain in middle-age groups and Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, and Philippines where this proportion was fairly homogenous across all age groups. The variation across countries for each demographic group is also illustrated in Figures S1–S34 in the Supplementary Information (SI).

It is worth noting that Table 3 does not include proportions across religious affiliation categories and race or ethnicity as these vary by country. As Table 3 shows results pooling all countries together, we only included the demographic categories that used the same categories across countries. For the countries in which these variables were available, proportions of people in pain across religious affiliation categories and race or ethnicity can be found in Tables S23–S44 in the Supplementary Information.

Table S45 in the Supplementary Information provides analyses that complement the analyses presented in Table 3. While Table 3 shows a random effects meta-analysis that treats each person in the 22 countries equally by assuming that the proportion in each country was drawn from the underlying distribution of the 22 countries included in the study, Table S45 shows a population-weighted meta-analysis in which each country’s results were weighted by the actual 2023 population size. Results across both analyses are mostly aligned.

Overall, the analyses presented in Table 3, Tables S23–S44, and Table S45 confirm hypothesis 3 of this study: Pain exhibits variations across different demographic categories which at the same time vary by country.

To shed light on the different proportion of people in pain across demographic categories, we conducted additional analyses that compare the demographic categories in each country. These results can be found in Figs. S35–S115 in the SI. As one example, Fig. S35 shows the difference in the proportion of people in pain for the 25–29 age group in comparison to the 18–24 age group. In this case, all differences are statistically insignificant suggesting that there is no difference in the proportion of people in pain across these two categories in any of the countries. However, Fig. S49 shows that the proportion of people in pain is smaller in the age group 50–59 than in the age group 30–39 in South Africa, Poland, Sweden, and Germany whereas in all the other countries the difference in the proportion of people in pain across these two age groups is statistically insignificant.

Discussion

In this study, we used a nationally representative dataset with 202,898 individuals from 22 countries to explore the proportion of people in pain across key demographic groups and across countries.

Our results show substantial country-specific variation. For instance, using a mid-point dichotomization of our pain variable, Egypt (0.60), Brazil (0.59), Australia (0.56), and Turkey (0.53) were among the countries with the greatest proportion of people in pain whereas Israel (0.25), South Africa (0.29), Poland (0.32), and Japan (0.33) showed the smallest proportions. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution. These differences might be due to a number of factors such as differing demographic distributions across countries including age and life expectancy, access to healthcare, macroeconomic conditions, and possible seasonal effects. These differences might also be explained by the interpretation of our dependent variable. For example, the question asks about “bodily pain” which might have different meaning to different people. In line with this idea, our dependent variable does not allow us to explore the type of pain, for example, whether bodily pain is chronic or acute.

It is worth noting that some differences emerge when using different dichotomization points of our pain variable. For example, when using all types of pain vs no pain, Philippines appears at the top of the ranking together with Australia. When focusing on severe pain, India moves to the top of the ranking. Besides these differences, countries mostly appear in the same quantile as in the original analyses. These differences might be explained by the fact that some people might underrate or overrate their pain. Future research should explore cross-cultural reporting styles of pain.

Using a random effects meta-analysis, we examined the proportion of people in pain across each demographic group across the 22 countries together. We found the highest proportion of people in pain among women and other gender groups, individuals who were widowed, those who were retired, those who had low level of education, and those who attended a religious service more than once a week. These findings are in line with prior work that showed greater levels of pain among women2, the widowed5, people who were retired14, individuals with low level of education7, and people who attended religious services more frequently13. These are all descriptive analyses and should not necessarily be interpreted causally. For instance, while it is possible that religious service attendance makes one more sensitive to pain, it is also possible that those in pain seek relief by attending religious services more often. The potential link among demographic factors should also be considered. For instance, it might be the case that people who are retired reported greater pain because they tend to be older than those who are not retired. The same can happen with religious service attendance: people who attend religious services more frequently might be older than those who attend religious services less frequently and their pain might be due to their age. The demographic descriptive statistics simply inform us of the proportion of people in pain in each demographic category. Additional data will be collected every year within the Global Flourishing Study20. This longitudinal data will provide a more comprehensive overview of the role of demographic variables in pain as well as the direction of relationships.

The age groups results deserve special attention. In the aggregated analysis shown in Table 3, we found the highest proportion of people in pain among older age groups. Although prior work has found that the level of pain was higher among the elderly than among the younger42, related research has found a rapid increase in the percentage of people in pain in middle-age groups2,7. In our analysis, countries like Australia, Brazil, Egypt, and the United States show high proportions of people in pain in middle-age groups. Our detailed comparison of categories within each demographic factor in each country (Figs. S35–S115 in the SI) also supports the idea that the age-pain link might be country-specific. We believe that the data collected in the next few years as part of the Global Flourishing Study20 will help to shed further light on the role of age in pain. These findings should not, however, be generalised to other countries not included in our sample.

By documenting the proportion of people in pain across key demographic groups and across countries worldwide, this study provides foundational insights on the new literature on the social determinants of pain. We hope that these findings are helpful for scientists across the medical, social, economic, and behavioural sciences.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this article are openly available on the Open Science Framework. The specific dataset used was Wave 1 non-sensitive Global data https://osf.io/sm4cd/ available February 2024 - March 2026 via preregistration and publicly from then onwards. Researchers interested in working with these data before March 2026, need to preregister their analysis. No specific additional registration is needed to access the data.

All analyses were preregistered with COS prior to data access (https://osf.io/ewyr5/?view_only=1fceb9e7dac440a88ad1d5764a6ea6bd, see also Supplementary Note 1 in the Supplementary Information).

Code availability

All code to reproduce analyses are openly available in an online repository22.

References

Raja, S. et al. The revised IASP definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 161, 1976–1982 (2020).

Macchia, L. Pain trends and pain growth disparities, 2009–2021. Econ. Hum. Biol. 47, 101200 (2022).

Rikard, S. M., Strahan, A. E. & Schmit, K. M. Chronic pain among adults—United States, 2019–2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. (MMWR) 72, 379–385 (2023).

National Health Service. Best practice solutions—Musculoskeletal. https://www.england.nhs.uk/elective-care-transformation/best-practice-solutions/musculoskeletal/ (2022).

Macchia, L., Delaney, L. & Daly, M. Global pain levels before and during the COVID-19 pandemic Global pain levels before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Econ. Hum. Biol. 52, 101337 (2024).

Case, A. & Deaton, A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15078–15083 (2015).

Case, A., Deaton, A. & Stone, A. A. Decoding the mystery of American pain reveals a warning for the future. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24785–24789 (2020).

Janevic, M. R., McLaughlin, S. J., Heapy, A. A., Thacker, C. & Piette, J. D. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in disabling chronic pain: findings from the health and retirement study. J. Pain. 18, 1459–1467 (2017).

Kennedy, J., Roll, J. M., Schraudner, T., Murphy, S. & McPherson, S. Prevalence of persistent pain in the U.S. adult population: New data from the 2010 national health interview survey. J. Pain. 15, 979–984 (2014).

Patel, K. V., Guralnik, J. M., Dansie, E. J. & Turk, D. C. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States: Findings from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. Pain 154, 2649–2657 (2013).

Zimmer, Z., Zajacova, A. & Grol-Prokopczyk, H. Trends in pain prevalence among adults aged 50 and older across Europe, 2004 to 2015. J. Aging Health 32, 1419–1432 (2020).

Todd, A. et al. The European epidemic: pain prevalence and socioeconomic inequalities in pain across 19 European countries. Eur. J. Pain. 23, 1425–1436 (2019).

Tronvik, E. et al. The relationship between headache and religious attendance (the Nord-Trøndelag health study- HUNT). J. Headache Pain. 15, 1–7 (2014).

Macchia, L. & Oswald, A. J. Physical pain, gender, and the state of the economy in 146 nations. Soc. Sci. Med. 287, 114332 (2021).

Macchia, L. Having less than others is physically painful: Income rank and pain around the world. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 15, 215–224 (2023).

Tang, C. K., Macchia, L. & Powdthavee, N. Income is more protective against pain in more equal countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 333, 116181 (2023).

Zimmer, Z., Fraser, K., Grol-Prokopczyk, H. & Zajacova, A. A global study of pain prevalence across 52 countries: examining the role of country-level contextual factors. Pain 163, 1740–1750 (2022).

VanderWeele, T. J. et al. The Global Flourishing Study: study profile and initial results on flourishing. Nat. Ment. Health (2024).

Crabtree, S., English, C., Johnson, B. R., Ritter, Z. & VanderWeele, T. J. Global Flourishing Study: questionnaire development report. Gallup Inc. https://osf.io/y3t6m (2021).

Johnson, B. R. et al. The Global Flourishing Study. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/3JTZ8 (2024).

Padgett, R. N. et al. Analytic methodology for childhood predictor analyses for Wave 1 of the Global Flourishing Study. BMC Global Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44263-025-00142-0 (2025).

Padgett, R. N. et al. Global Flourishing Study statistical analyses code. Preprint available at https://doi.org/10.17605/Osf.Io/Vbype (2024).

Ritter, Z. et al. Global Flourishing Study Methodology. Gallup Inc. https://osf.io/k2s7u (2024).

Lomas, T. et al. The development of the Global Flourishing Study questionnaire: charting the evolution of a new 109-Item inventory of human flourishing. BMC Global Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44263-025-00139-9 (2025).

Padgett, R. N. et al. Survey sampling design in wave 1 of the Global Flourishing Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-024-01167-9 (2025).

Vanderweele, T. J. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8148–8156 (2017).

Johnson, K. A., Moon, J. W., VanderWeele, T., Schnitker, S. & Johnson, B. R. Assessing religion and spirituality in a cross-cultural sample: development of religion and spirituality items for the Global Flourishing Study. Relig. Brain Behav. 0, 1–14 (2023).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T. & Rothstein, H. R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1, 97–111 (2010).

Hunter, J. E. & Schmidt, F. L. Fixed effects vs. random effects meta-analysis models: Implications for cumulative research knowledge. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 8, 275–292 (2000).

Mathur, M. B. & VanderWeele, T. J. Sensitivity analysis for publication bias in meta-analyses. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 69, 1091–1119 (2020).

R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. The R Project for Statistical Computing (2024).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48 (2010).

Wilson, D. J. The harmonic mean p-value for combining dependent tests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1195–1200 (2019).

Abdi, H. Bonferroni and Šidák corrections for multiple comparisons. Encycl. Meas. Stat. 3, 2007 (2007).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Mathur, M. B. Some desirable properties of the Bonferroni correction: Is the Bonferroni correction really so bad? Am. J. Epidemiol. 188, 617–618 (2019).

Acock, A. C. Working with missing values. J. Marriage Fam. 67, 1012–1028 (2005).

Rubin, D. B. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 91, 473–489 (1996).

Sterne, J. A. C. et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 338, b2393 (2009).

van Burren, S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data 2nd edn (CRC Press, 2023).

Little, R. J. & Rubin, D. B. Statistical analysis with missing data. (John Wiley & Sons, 2019).

Padgett, R. N. et al. Analytic methodology for demographic variation analyses for Wave 1 of the Global Flourishing Study. BMC Global Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44263-025-00140-2 (2025).

Zajacova, A., Grol-Prokopczyk, H. & Zimmer, Z. Pain trends among American adults, 2002-2018: patterns, disparities, and correlates. Demography 58, 711–738 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The Global Flourishing Study was supported by funding from the John Templeton Foundation (grant #61665), Templeton Religion Trust (#1308), Templeton World Charity Foundation (#0605), Well-Being for Planet Earth Foundation, Fetzer Institute (#4354), Well Being Trust, Paul L. Foster Family Foundation, and the David and Carol Myers Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.M. Conducted the data analysis, and wrote the paper. C.N.O. Provided helpful comments to the written drafts. T.B. Provided helpful comments to the written drafts. K.S. Provided code for data analysis. A.P. Provided helpful comments to the written drafts. B.R.J. Coordinated data collection, participated in survey design, coordinated creation of code for analysis, and provided helpful comments to the written drafts. T.J.V. Coordinated data collection, participated in survey design, coordinated creation of code for analysis, and provided helpful comments to the written drafts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: Tyler VanderWeele reports consulting fees from Gloo Inc., along with shared revenue received by Harvard University in its license agreement with Gloo according to the University IP policy. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Macchia, L., Okafor, C.N., Breedlove, T. et al. Demographic variation in pain across 22 countries. Commun Med 5, 154 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00858-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00858-y

- Springer Nature Limited