Abstract

Layered transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) are commonly classified as quasi-two-dimensional materials, meaning that their electronic structure closely resembles that of an individual layer, which results in resistivity anisotropies reaching thousands. Here, we show that this rule does not hold for 1T-TaS2—a compound with the richest phase diagram among TMDs. Although the onset of charge density wave order makes the in-plane conduction non-metallic, we reveal that the out-of-plane charge transport is metallic and the resistivity anisotropy is close to one. We support our findings with ab initio calculations predicting a pronounced quasi-one-dimensional character of the electronic structure. Consequently, we interpret the highly debated metal-insulator transition in 1T-TaS2 as a quasi-one-dimensional instability, contrary to the long-standing Mott localisation picture. In a broader context, these findings are relevant for the newly born field of van der Waals heterostructures, where tuning interlayer interactions (e.g., by twist, strain, intercalation, etc.) leads to new emergent phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite remaining at the forefront of research for more than a decade1, quasi-two-dimensional materials still provide a vast playground for discovery of novel electronic behaviour, showing promise for a variety of technological applications2,3. Prominent among the recent advances in the field is the demonstration of how new phenomena can be induced in known compounds by tuning the interlayer interaction, as exemplified by the unconventional superconductivity and strong electronic correlations in magic-angle graphene superlattices4 or long-lived excitons in heterobilayers of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)5,6. Characterisation of the coupling between the layers in van der Waals materials is therefore of great interest, and valuable information can be revealed by probing the out-of-plane charge transport. However, contrary to its in-plane counterpart this property has not been given a lot of attention so far, with the existing data being rather scarce and in some cases inconsistent7,8,9,10,11. With the aforementioned discoveries in mind, one can raise a question: to what extent can various layered materials be really classified as quasi-two-dimensional?

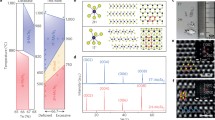

1T-TaS2 stands out from the other conducting TMDs with its remarkably rich pressure–temperature phase diagram (Fig. 1a), containing a record number of distinct charge density wave (CDW) orders of diverse electronic properties12. The commensurate (C) CDW phase is characterised by the \(\sqrt {13} \times \sqrt {13}\) reconstruction (Fig. 1b), which is manifested in a superlattice of David-star-shaped clusters (abbreviated as DS) of 13 Ta and 26 S atoms13. At room temperature, 1T-TaS2 assumes the so-called nearly commensurate (NC) CDW order, occurring uniquely in this compound. While the periods of the charge density modulation and the lattice in the NC phase are incommensurate, the deviation from the commensurability is so small that the \(\sqrt {13} \times \sqrt {13}\) reconstruction can still take place over a few-nanometre range. As a result, the DS become organised into a nano-array of hexagonal domains, which are separated by regions of aperiodically distorted lattice (discommensurations). In the direction perpendicular to the layers the domains obey the face-centred cubic packing, with a three-layer periodicity14 (Fig. 1e). Lowering temperature causes the NC to C phase transition, accompanied by a sizeable jump in resistivity. This change can, however, be reversed via an application of light or current pulse, which makes the material a promising candidate for applications in devices11,15,16,17. The pronounced sensitivity of the NC to C phase transition to the sample thickness16,18 implies that the interlayer interactions play a fundamental role in the process, which further motivates the investigation of the out-of-plane charge transport.

a Pressure–temperature phase diagram of 1T-TaS2 based on the resistivity data of Sipos et al.12 and this study. The labels stand for commensurate (C), nearly commensurate (NC), triclinic (T) and incommensurate (IC) charge density wave phases, as well as the superconducting (SC) phase. The black lines represent the approximate phase boundaries. The striped areas indicate the regions where hysteresis occurs upon heating and cooling. The triclinic phase is observed only during a warm-up. Superconducting transition temperature is multiplied by 10 for clarity. b Visualisation of the in-plane displacement of Ta atoms (red arrows), leading to the formation of a 13-atom David-star-shaped cluster (blue outline). c, d Schematic illustration of the in-plane lattice distortions in the commensurate c and nearly commensurate d charge density wave phases. The David-star clusters are marked with the dark blue outlines. Light blue dots stand for the Ta atoms. The purple mesh represents locally aperiodic reductions of Ta–Ta distances. e Schematic visualisation of the ab-plane projection of the interlayer stacking of the reconstructed domains in the NC phase. Blue, red and green hexagons represent the domains in three consecutive layers. The red outline marks a region where the domains overlap throughout the whole c axis period.

Given the intriguing functional properties of 1T-TaS211,15,16,17, there still exist open questions concerning the electronic structure of the compound. First, there is an active ongoing debate regarding the insulating nature of the C phase, which has traditionally been regarded as a Mott insulator19. Although such attribution is in line with a number of spectroscopic investigations20,21,22, the correlated insulator picture has been challenged by recent band structure calculations23,24, which relate the formation of the band gap to the interlayer stacking order of the DS25,26. Second, the NC phase displays a rather atypical negative temperature coefficient of the in-plane resistivity12,16,18,27, a solid interpretation of which has not been proposed so far.

We conducted a highly accurate investigation of the in-plane and out-of-plane electrical resistivities (ρǁ and ρ⊥, respectively) of bulk monocrystalline 1T-TaS2 across all the different CDW phases. We reveal that resistivity anisotropy (ρ⊥/ρǁ) in the compound is, astoundingly, of the order of one. Furthermore, we find that the NC phase is a conventional metal in the out-of-plane direction, in stark contrast to the in-plane behaviour, characterised by the negative temperature coefficient of resistivity, which we relate the composite nature of the lattice. Aided by band structure calculations, we attribute the interlayer metallicity to a formation of quasi-one-dimensional electronic states extending along the c axis of the crystal. Consequently, we regard the metal-insulator transition as a quasi-one-dimensional instability—a notion favouring the band insulator nature of the C phase. Our results paint a peculiar picture: owing to the unique structure of 1T-TaS2 in the NC phase, its in-plane charge transport is substantially suppressed compared with the more common states of metallic TMDs7,8, yet simultaneously, the out-of-plane conduction preserves the coherent metallic character, making the compound an effectively three-dimensional conductor with highly anisotropic electronic properties.

Results

Anomalously low resistivity anisotropy

A major hindrance to a systematic study of the interlayer resistivity in quasi-two-dimensional materials is the characteristic morphology of the available single crystals, which typically have very limited extent along the c axis compared with their lateral dimensions28. Such a shape makes it difficult to constrain the current flow in a direction strictly perpendicular to the layers. Furthermore, the intrinsic physics can become obscured by effects caused by crystallographic defects or delamination, which are often prevalent due to weak mechanical interlayer coupling. Many of these problems can be overcome by employing focused ion beam (FIB) microstructuring, which has been utilised with great success for probing charge transport in solid-state systems29 and was essential in making an accurate measurement of ρ⊥ of 1T-TaS2 possible. To prepare a sample (shown in Fig. 2a), a monocrystalline lamella, with its plane parallel to the c axis, was extracted from a larger crystal and shaped into a microstructure, which ensured a well-defined measurement geometry, absence of current jetting effects30 and minimised the mechanical stresses. Measurements of ρ⊥ and ρǁ were conducted simultaneously, using the same microstructure. We developed an optimal sample preparation procedure (described in the Methods section), which minimised the destructive shear stresses experienced by a microstructure upon changing temperature or applying pressure (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Figure 1 describe the damage shear stresses can cause and how the effect can be mitigated).

a Scanning electron microscope image of the bulk monocrystalline sample of 1T-TaS2 prepared using focused ion beam. False colouring is used for illustrative purposes. The arrows indicate the orientation of the crystal (purple). A layer of gold (beige) formed the conductive paths between the crystal and external leads. The rectangular ramps, created using in situ platinum deposition, provide mechanical stability and improve the continuity of the gold layer. The scale bar in the top–right corresponds to a 50 µm distance. b Temperature dependence of electrical resistivities of 1T-TaS2 measured on the microfabricated sample. The bar below the curves indicates temperature intervals corresponding to the different phases encountered upon heating (solid line) and cooling (dashed line). Sharp features accompanying the jump in resistivity near 135 K appear owing to temporary internal stresses experienced by the sample as a result of a rapid volume change during the phase transition. c Ratio of interlayer to intralayer resistivities (ρ⊥/ρǁ) of 1T-TaS2 as a function of temperature. d Comparison between the room temperature in-plane and out-of-plane resistivity values of 1T-TaS2 and two other metallic transition metal dichalcogenides: 2H-TaSe2 and 2H-NbSe2. All samples were microstructured with focused ion beam.

The previously published values of resistivity anisotropy of 1T-TaS2 in the C and NC phases are in the range of hundreds10 and thousands11, which is suspiciously high given the results of recent band structure calculations and angle resolved photoemission spectroscopy experiments, indicating a sizeable band dispersion along the kz axis of the Brillouin zone31,32,33,34,35. A plot of our data for ρ⊥ and ρǁ of 1T-TaS2 between 2 K and 400 K (Fig. 2b) presents comparable resistivity values for the two current directions. In the temperature range between 1.8 K and 400 K, the anisotropy varies between 0.6 and 4.3 (Fig. 2c), which is on average more than two orders of magnitude smaller than the published values10,11. Transitions from the incommensurate CDW to NC and then to the C phase upon cooling are accompanied by discontinuous reductions of anisotropy. A clear signature of the triclinic phase36, which is typically much less pronounced in the existing literature, can be seen in the warm-up curve between 230 K and 270 K. However, the most remarkable behaviour is associated with the NC phase, in which ρǁ increases upon cooling but ρ⊥ is clearly metallic.

With the help of finite element simulations (presented in the Supplementary Note 2 as well as Supplementary Figures 2, 3, 4) we verified that the chosen geometry of the sample is expected to give reliable resistance readings for a range of hypothetical anisotropy values between ~0.1 and 100. Furthermore, we analysed the probing geometries that had been used in earlier measurements of the c axis resistivity of 1 T-TaS210,11 and identified the shortcomings explaining why the previously published data are so different from ours (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figures 5, 6, 7, 8).

Given the interlayer stacking of the DS domains in the NC phase (Fig. 1e), we note that any straight path parallel to the c axis passes through a DS domain at least once every three layers. This implies that the out-of-plane metallicity is the intrinsic property of the domains, unless the conduction happens percolatively, via the discommensurations. Further insight can be gained by comparing 1T-TaS2 with two other TMDs, 2H-TaSe2 and 2H-NbSe2, known to possess c axis metallicity from earlier far-infra-red optical reflectivity measurements and having homogeneous in-plane structure7,8. FIB-prepared samples were used to obtain values of room temperature resistivity for the two principal directions. As can be seen in Fig. 2d, all three materials show comparable ρ⊥ close to 1 mΩcm, which rules out the percolation scenario for the c axis conduction. At the same time, ρǁ of 1T-TaS2 at room temperature is nearly six times higher than for 2H-TaSe2 and 2H-NbSe2. This suggests that the anomalously low resistivity anisotropy in the NC phase of 1T-TaS2 is largely a consequence of the enhanced ρǁ, whereas the changes in ρ⊥ are secondary in that regard. This situation remotely resembles the case of the quasi-one-dimensional conductor BaVS3, where the on-chain correlations strongly enhance intrachain resistivity, but hardly influence the interchain hopping, which manifests as a very low resistivity anisotropy37.

Counterintuitive direction dependence of charge transport character

The NC phase of 1T-TaS2 can be stabilised over a broader temperature with an application of moderate hydrostatic pressure12,27. We employed this approach in order to investigate the low-temperature charge transport in the NC phase and its reaction to the reduction of interlayer spacing. The measured ρǁ (Fig. 3a) is consistent with the published results12,27. Applying pressure of 0.9 GPa resulted in a full suppression of the C phase, revealing that ρ⊥ in the NC phase remains metallic down to the lowest temperatures (Fig. 3b). Further increase of pressure caused the shape of the low-temperature part (0–30 K) of ρ⊥ go from approximately linear to quadratic (Fig. 3c inset), typical for Fermi-liquid metals, likely as a result of stiffening of the phonon modes and establishment of electron–electron interactions as the dominant source of scattering. Presence of stacking disorder could explain the rather low residual resistivity ratio. In Fig. 3c we plot ρ⊥(T) and ρǁ(T) for the highest achieved pressure of 2.1 GPa to emphasise the abnormal contrast between the two conduction characters. On cooldown, the anisotropy goes from the room temperature value of 2 down to as little as 0.2, contradicting the intuitive quasi-two-dimensional view of the material. In the subsequent sections of this paper we attempt to rationalise these perplexing observations.

a, b In-plane a and out-of-plane b electrical resistivities of 1T-TaS2 (ρǁ and ρ⊥, respectively) as functions of temperature for different applied hydrostatic pressures. c Temperature dependences of resistivities along the two directions at 2.1 GPa pressure. The inset shows a quadratic power-law fit to the out-of-plane resistivity between 7 K and 30 K.

Suppressed in-plane conduction in the nearly commensurate CDW phase

Given that the DS domains and the discommensurations in the NC phase are individually intrinsic in-plane conductors, one can naively attempt to explain the negative dρǁ/dT with a parallel resistor model, assuming that the overall conductivity is a sum of two independent contributions. Upon cooling, the geometry of the domain lattice continuously changes from honeycomb-like (side-sharing arrangement) to Kagome-like (corner-sharing arrangement)38. Simultaneously, the domains grow and their centres move away from each other, but the discommensuration network always remains continuous (we note that the perfect Kagome-type or honeycomb-type domain lattice pictures, which are often used in the literature12,15,39, are oversimplifications in the current context). Our powder X-ray diffraction data show that pressure increase leads to the same transformation as during a warm-up, and we visualise it in Fig. 4 (additional crystallographic data are presented in the Supplementary Note 4 and the Supplementary Figures 9, 10, 11). On lowering temperature, the rotation towards the Kagome-like arrangement constricts the discommensuration channels, reducing their contribution towards the overall conductivity, which might explain its decrease. To verify such model we approximate the aperiodic discommensurations (~30% of the in-plane area) with the incommensurate phase of 1T-TaS2 (\(\rho _\parallel \approx 0.25\) mΩcm at 360 K), and the DS domains with the commensurate phase of 1T-TaSe2 (metallic and isostructural to 1T-TaS2, \(\rho _\parallel \approx 1.5\) mΩcm at 300 K)40. At room temperature the NC phase has \(\rho _\parallel \approx 0.7\) mΩcm, which is consistent with the expectations, but the value of \(\rho _\parallel \approx 1.7\) mΩcm at 130 K cannot be explained by the model, as both 1T-TaSe2 and the incommensurate CDW phase of 1T-TaS2 both become substantially more conductive upon cooling12,40. We therefore conclude that either the DS domains are intrinsically much more resistive along the in-plane directions than commensurately reconstructed 1T-TaSe2, or an additional scattering mechanism must be behind the negative dρǁ/dT.

Room temperature in-plane lattice structures in the nearly commensurate phase of 1T-TaS2 at ambient pressure (left) and at 1.6 GPa (right), visualised based on the powder X-ray diffraction data. Ta atoms are represented by dots, which are connected if the interatomic separation is below an arbitrarily chosen threshold value. The hexagonal outlines mark the commensurately reconstructed domains with the incomplete David-star-shaped clusters included (solid blue) or excluded (dashed cyan). Temperature (T) and pressure (P) increases both individually lead to the same transformation—rotation from corner-sharing towards side-sharing arrangement, shrinkage of domains and reduction of the domain lattice period.

We refer to the far-infra-red reflectivity data41, noting that the real part of the in-plane conductivity lacks the low-frequency Drude peak, characteristic for conventional metals42. Such suppression of charge transport in the direct current limit happens to be rather common for nanoscale-structured systems43, where it is attributed to directionally biased boundary scattering, captured by the Drude-Smith model44. Alternatively, the aperiodicity of the NC phase prompts a comparison with certain species of quasicrystals, which also exhibit suppression of the Drude peak45, and where absence of Bloch waves causes ρ(T) to have a negative slope and follow effectively the same shape in quasiperiodic directions, given a typical metallic behaviour along the periodic one46. A more precise determination of the microscopic origin of the negative dρǁ/dT in the NC phase would require a separate study.

Quasi-one-dimensional states as a source of metallic out-of-plane conduction

As the DS domains in the NC phase of 1T-TaS2 must contribute to the out-of-plane metallicity, it follows that the same \(\sqrt {13} \times \sqrt {13}\) reconstruction in the NC and C phases results in, respectively, metallic and insulating states. This is consistent with the results of recent density functional theory (DFT) calculations23,24,32,33, indicating that the electronic band structure of commensurately distorted 1T-TaS2 varies substantially depending on the interlayer stacking of DS, and that the insulating nature of the C phase is, in fact, a consequence of a special stacking order rather than Mott localisation. Moreover, the studies predicted significantly stronger energy-momentum dispersions along the ГA direction of the Brillouin zone than in the ГMK plane, along with favoured c axis conduction, which has not been experimentally observed until now.

To assist our interpretation of the resistivity data we conducted DFT calculations for a different possible configurations of the commensurate superlattice. Given the strong electron–phonon and, possibly, electron–electron interactions in 1T-TaS2, we enabled the relaxation of the lattice and included the on-site Coulomb energy U. In all of the previous theoretical works either one or both of these ingredients have been neglected. As in Lee et al.24, we denote a configuration where for two successive layers the DS superlattices are vertically aligned with each other as the A stacking (Fig. 5a), and a configuration where the centre of a DS in one layer corresponds to an outermost Ta atom of a DS in a neighbouring layer (i.e., the DS avoid each other as much as possible) as the L stacking (Fig. 5b).

a, b Arrangements of the David-star-shaped clusters (only Ta atoms are shown) in successive layers of commensurately distorted 1T-TaS2, considered for our density functional theory (DFT) calculations. After ref. 24, we denote these stacking configurations as A a and L b. The red arrows join the Ta atoms sharing the same lateral position. The top–right sections of both panels display the first Brillouin zones for the corresponding lattices in relation to the first Brillouin zone for the undistorted 1T-TaS2. c, d The respective electronic band structures and densities of states (DOS) predicted by the DFT calculations for relaxed lattices and with the on-site electron–electron interaction energy U = 2.41 eV. The directions traced in the reciprocal space are marked in a and b. Each colour stands for a different band. e, f The respective Fermi surfaces. The extended open sheets in both cases indicate a quasi-one-dimensional character of the electronic structures. g Conductivity ellipsoid calculated from the electron energy dispersion near the Fermi surface (i.e., assuming isotropic relaxation time), in relation to the crystal structure for the L stacking. The longest axis of the ellipsoid indicates the direction of the highest conductivity. The ellipsoid is slightly slanted (~8°) with respect to the line connecting the centres of two nearest-neighbour clusters in two adjacent layers. The ratios of the highest conductivity to the conductivities along the two shorter principal axes of the ellipsoid are ~13 and 5.

In the case of A stacking, the obtained band structure (Fig. 5c) has even lower dispersion in the ГMK plane than suggested by the earlier studies and an effectively flat Fermi surface (Fig. 5e). According to the Boltzmann transport model, we can estimate the resultant resistivity anisotropy by considering the ratio of the Fermi surface-averaged squares of the in-plane and out-of-plane Fermi velocity components. Astonishingly, the predicted value of ρ⊥/ρǁ for the modelled state is ~0.023, whereas the analogous value for the completely undistorted lattice is as high as 40. The electronic structure of the L-stacked crystal is much more three-dimensional (Fig. 5d, f, g), but the density of states and the Fermi surface still have a pronounced quasi-one-dimensional character. Based on the orientation of the conductivity ellipsoid (Fig. 5g), the direction of maximal conductivity approximately follows the line connecting a DS to its nearest neighbour in an adjacent layer. The predicted ratios between the resistivity along the most conductive direction and the resistivities along the other two principal axes of the ellipsoid are ~0.077 and 0.2. The electronic dispersion along Г-K-M-Г path in Fig. 5d is predominantly caused by the slanting of the “line-of-stars” (dashed line in Fig. 5g) with respect to the c axis. The effect of slanting, particular to the L stacking, should not be confused with a relatively minor effect of the in-plane DS hybridisation and its contribution to the in-plane conductivity.

The presented calculations indicate that for both types of stacking, the commensurate DS superlattice develops a single-band quasi-one-dimensional dispersion in a wide window around the Fermi energy. This means that each DS effectively has a single electronic orbital, and that the nearest-neighbour tight-binding overlap between these orbitals is always significantly better for two DS’s in successive layers than for a pair of DS’s in the same layer. These overlaps form chains that follow the sequence of nearest-neighbour DS’s in adjacent layers, with each DS having only one nearest-neighbour DS in any of the adjacent layers (plots of electron density throughout the A-stacked and L-stacked lattices are presented in the Supplementary Figure 12 and discussed in the Supplementary Note 5). Presence of these DS chains explains the coherent c axis charge transport in 1T-TaS2. In the NC phase, the DS domains in adjacent layers partially overlap, and according to the published crystallographic data14, in each overlap the DS’s follow one of the three possible orientations of the L stacking (L, I and H types according to Lee at al.24). We therefore expect the orbital chains to exist in the NC phase in the regions where the domain overlap persists over a sizeable number of layers (see Fig. 1e). Given that these regions occupy only a fraction of the in-plane area, the intrinsic resistivity of the DS chains is likely even lower than the experimentally obtained value of ρ⊥ for the NC phase. In the absence of structural dimerisation, and with sufficiently small amount of stacking disorder, the metallicity of the chains is expected to survive.

DFT calculations performed without the inclusion of the Coulomb energy U produced electronic structures with slightly more pronounced three-dimensional characters (presented in the Supplementary Note 6 and the Supplementary Figure 13) yet the overall picture remains qualitatively the same as in the finite U case.

Metal-insulator transition in 1T-TaS2 as a quasi-one-dimensional instability

The proposed formation of c axis oriented conducting chains in the NC phase has interesting implications in the context of the metal-insulator transition in 1T-TaS2. Specifically, the NC to C phase transition can be regarded as a quasi-one-dimensional instability, driven by the energy gain from the modulation of the interlayer hybridisation of the DS orbitals. The mechanism resembles the Peierls instability—a metal-insulator transition occurring as a result of a dimerisation of a one-dimensional chain. However, such a comparison is very superficial given the continuous nature of the order parameter in genuine Peierls systems. In 1T-TaS2 the change of the CDW modulation occurs in a discontinuous manner, through a discrete change of DS stacking, which explains the first order type of the phase transition. The proposal to view the insulating state of the C phase as a consequence of the particular stacking order has recently been made by Ritschel et al.23 and Lee at al24. The idea has been discussed with a meticulous comparison of cohesive energies and bands structure calculations for various stacking orders, and it decisively challenged the long-standing Mott localisation scenario. However, there has so far been no direct experimental observation of the out-of-plane-metallic state in the NC phase of 1T-TaS2, serving as a precursor in the stacking order localisation picture. This gap is conveniently filled by our resistivity data, revealing the c axis metallicity in the NC phase. Simultaneously, our DFT calculations show that the interlayer DS hybridisation is a major consequence of structural relaxations, fully unconstrained with respect to the positions of atoms within the supercell, and the lattice constants in all directions. The interlayer DS hybridisation also shows independently of the imposed Bravais lattices types, choice of which leads to spontaneous formations of the different types of DS stacking.

Discussion

To summarise, by employing the state-of-the-art FIB-based sample preparation process, we conducted reliable and accurate measurements of the in-plane and out-of-plane electrical resistivities of 1T-TaS2 in multiple CDW phases. The experiments revealed unusually anisotropic charge transport character in presence of the NC CDW order: the out-of-plane conduction is metallic, yet for the in-plane direction the material becomes less conductive upon cooling. We point out the substantial enhancement of the in-plane resistivity, compared with the typical values observed in other metallic TMDs, and conclude that the aperiodic and composite structure of the phase is likely at the root of this effect. At the same time, the out-of-plane conduction is favoured by the formation of the quasi-one-dimensional c axis oriented chains of electronic orbitals, propagating through the overlapping regions of DS domains and serving as a source of previously unobserved coherent c axis metallicity—a description supported by our DFT calculations. Consequently, the layered material has an uncharacteristically low resistivity anisotropy, exhibiting nearly five times lower out-of-plane resistivity than the in-plane one under certain conditions. Moreover, we interpret the NC to C phase transition as a quasi-one-dimensional instability, and support the idea of the C phase being a band insulator, rather than a Mott state, as has been thought previously. Our findings are also of value to the efforts aimed at functionalising the compound. Exploiting the interlayer conduction nearly doubles the resistivity change upon the low-temperature phase switching, compared with the difference seen in the in-plane charge transport, leading to a more robust performance of a potential device. Furthermore, miniaturisation and production scalability requirements additionally favour utilisation of the out-of-plane charge transport. 1T-TaS2 serves as a neat example of how interlayer interactions in a van der Waals material lead to unexpected properties, warranting a more systematic study of resistivity anisotropy in other compounds.

Methods

Synthesis of 1T-TaS2 single crystals

The single crystals of 1T-TaS2 were prepared from the elements using the chemical vapour transport technique via a reversible chemical reaction with iodine as a transport agent, between 950 °C (hot zone) and 900 °C (cold zone). The 1T-polytipic phase is obtained by the addition of SnS2 (less than 0.5% in weight) and by rapid cooling from the growth temperature47.

Focused ion beam microfabrication

Samples of 1T-TaS2 used for this study were extracted from monocrystalline flakes of ~100 μm thickness and the lateral size of the order of 1 mm. In order to produce the sample shown in Fig. 2a, a Helios G4 Xe Plasma FIB microscope, manufactured by FEI, was first used for isolating a rectangular lamella of 115 μm length, 60 m width and 4-μm thickness from the single crystal by milling away the surrounding material. For this process the ion column voltage and the beam current were set, respectively, to 30 kV and 60 nA. The 60 μm long edges of the lamella were aligned with the c axis of the crystalline lattice. After the lamella was extracted, its surface was polished via grazing angle milling at a significantly lower beam current of 1 nA. This procedure ensured the parallelism of the two largest faces of the sample. The lamella was subsequently positioned on a sapphire substrate with the largest face parallel to the surface. The exposed surfaces of the lamella and the substrate were etched by argon plasma for 5 minutes and sputter-coated by a 5 nm titanium layer followed by a 150 nm gold layer at a 20° angle to the surface normal. We draw attention to the fact that no adhesive was used for attaching lamella to the substrate in order to reduce the effects of differential thermal contraction and compressibility during the subsequent experiments. The remaining FIB procedures were conducted in Helios G2 Ga FIB microscope (also produced by FEI). Pt contact points were grown by gas-assisted deposition. Clearly visible in Fig. 2a of the main text of the article, they acted both as electrical connections and anchoring points, securing the lamella on the substrate. The deposited material is amorphous and has a higher resistivity than a pure metal, therefore in order to make the final electrodes more conductive the specimen was sputter-coated by the second 100 nm layer of gold. The ion beam was then used to expose the surface of 1T-TaS2 by milling away the metal film from the surface of the desired current paths of the lamella. Using a beam current of the order of 10 nA the current channel was defined by milling a set of trenches. The current channel had three extended straight sections between 3 µm and 5 µm wide, two parallel and one perpendicular to the c axis of the crystal. Each of these sections had two branching points at which the voltages were probed. In order to improve the mechanical robustness of the structure, the concave edges were rounded. As a final step, all exposed faces of the sample along the current channel were finely polished with the ion beam of 1 nA current in order to reduce the surface roughness to the level of nanometres and remove most of the contaminated or damaged surface layer. The final dimensions of the sample, used for converting resistance to resistivity, were determined from the scanning electron microscope images.

Resistivity measurements

Resistivity was measured via the four-point technique with direct or alternating excitation currents in the 20–40 µA range. Temperature sweeps were conducted with the maximum rate of 1 K/min for the ambient pressure and of 0.5 K/min for the high-pressure measurements in order to avoid generating substantial temperature gradients.

A hydrostatic high-pressure environment for resistivity measurements was created using a piston cylinder cell produced by C&T Factory. 1:1 pentane–isopentane mixture was used as a pressure-transmitting medium (remains liquid at room temperature for up to ~6 GPa48). Pressure was determined from the changes in resistance and superconducting transition temperature of a sample of Pb located next to the 1T-TaS2 sample.

Powder X-ray diffraction measurements

The high-pressure powder X-ray diffraction data were collected at the BM01 Swiss–Norwegian beamline of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble. The beam had a wavelength of 0.7458 Å and a 100 × 100 nm size. PILATUS@SNBL detector49 was used for signal acquisition and the sample-detector distance was 146 mm. High pressures were generated with a diamond anvil cell using Daphne oil 7373 as the pressure-transmitting medium. Stainless steel gasket was pre-indented to 50 µm thickness and had a hole of 250 µm diameter. Pressure was determined from the shift in the fluorescence wavelength of ruby50. The sample was rotated by 4° to improve statistics. Integrations were done with only minimal masking using BUBBLE software49. CrysAlis PRO and JANA200651 software packages were used for data processing and structural refinement, respectively.

Density functional theory calculations

The density functional theory calculations were performed using the Quantum ESPRESSO package52, with ultrasoft pseudopotentials from Pslibrary53. The kinetic energy cutoff for wave functions was 70 Ry, whereas the kinetic energy cutoff for charge density and potential was 650 Ry. We used PBE exchange energy functional54 and Marzari–Vanderbilt smearing55 of the Fermi surface of 0.001 Ry. The Brillouin zone sampling used in self-consistent calculations was 6 × 6 × 12 k-points (with no shift). The Fermi surface were calculated with a denser mesh of 12 × 12 × 24 k-points. The on-site Coulomb interaction on Ta ions was taken into account within the DFT + U approach proposed by Cococcioni and de Gironcoli56. The Hubbard interaction U on Ta atoms was set to 2.41 eV. This choice of U is somewhat arbitrary and was guided by the values for U in 1T-TaS2 suggested by other authors31,57 (U = 2.27 eV and U = 2.5 eV), as well as the value (U = 2.94 eV) that we obtain for the undeformed 1T-TaS2 structure using the appropriate module within Quantum ESPRESSO58,59. The proper determination of U requires the self-consistent procedure where the calculation of the optimal structure is accompanied by the continuous re-evaluation of U60,61. For DS-based superstructures of 1T-TaS2 this is bound to produce a list of U’s with somewhat different value for each inequivalent Ta positions within the crystal. The convergence thresholds used for atomic structure relaxation were 0.0001 (a.u.) and 0.001 (a.u.) for the total energy and atomic forces, respectively. The DFT calculations without DFT + U corrections were made in the same manner.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors (E.M. and K.S.) upon reasonable request.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Two-dimensional atomic crystals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 10451–10453 (2005).

Fiori, G. et al. Electronics based on two-dimensional materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 768 (2014).

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Evidence of high-temperature exciton condensation in two-dimensional atomic double layers. Nature 574, 76–80 (2019).

Unuchek, D. et al. Room-temperature electrical control of exciton flux in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nature 560, 340–344 (2018).

Dordevic, S. V., Basov, D. N., Dynes, R. C. & Bucher, E. Anisotropic electrodynamics of layered metal 2H-NbSe2. Phys. Rev. B 64, 161103 (2001).

Ruzicka, B., Degiorgi, L., Berger, H., Gaál, R. & Forró, L. Charge dynamics of 2H-TaSe2 along the less-conducting c-axis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4136 (2001).

LeBlanc, A. & Nader, A. Resistivity anisotropy and charge density wave in 2H-NbSe2 and 2H-TaSe2. Solid State Commun. 150, 1346–1349 (2010).

Hambourger, P. D. & Di Salvo, F. J. Electronic conduction process in 1T-TaS2. Phys. B 99, 173–176 (1980).

Svetin, D., Vaskivskyi, I., Brazovskii, S. & Mihailovic, D. Three-dimensional resistivity and switching between correlated electronic states in 1T-TaS2. Sci. Rep. 7, 46048 (2017).

Sipos, B. et al. From Mott state to superconductivity in 1T-TaS2. Nat. Mater. 7, 960–965 (2008).

Rossnagel, K. On the origin of charge-density waves in select layered transition-metal dichalcogenides. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 23, 213001 (2011).

Spijkerman, A., de Boer, J. L., Meetsma, A., Wiegers, G. A. & van Smaalen, S. X-ray crystal-structure refinement of the nearly commensurate phase of 1T-TaS2 in (3+2)-dimensional superspace. Phys. Rev. B 56, 13757 (1997).

Stojchevska, L. et al. Ultrafast Switching to a Stable hidden quantum state in an electronic crystal. Science 344, 177–180 (2014).

Yoshida, M., Suzuki, R., Zhang, Y., Nakano, M. & Iwasa, Y. Memristive phase switching in two-dimensional 1T-TaS2 crystals. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500606 (2015).

Stahl, Q. et al. Collapse of layer dimerization in the photo-induced hidden state of 1T-TaS2. Nat. Commun. 11, 1247 (2020).

Yu, Y. et al. Gate-tunable phase transitions in thin flakes of 1T-TaS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 270–276 (2015).

Fazekas, P. & Tosatti, E. Charge carrier localization in pure and doped 1T-TaS2. Phys. B 99, 183–187 (1980).

Perfetti, L. et al. Femtosecond dynamics of electronic states in the Mott insulator 1T-TaS2 by time resolved photoelectron spectroscopy. N. J. Phys. 10, 053019 (2008).

Hellmann, S. et al. Ultrafast melting of a charge-density wave in the mott insulator 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 187401 (2010).

Ligges, M. et al. Ultrafast doublon dynamics in photoexcited 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 166401 (2018).

Ritschel, T., Berger, H. & Geck, J. Stacking-driven gap formation in layered 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 98, 195134 (2018).

Lee, S. H., Goh, J. S. & Cho, D. Origin of the insulating phase and first-order metal-insulator transition in 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 106404 (2019).

Ishiguro, T. & Sato, H. Electron microscopy of phase transformations in 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 44, 2046 (1991).

Naito, M., Nishihara, H. & Tanaka, S. Nuclear magnetic resonance and nuclear quadrupole resonance study of 181Ta in the commensurate charge density wave state of 1T-TaS2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 55, 2410–2421 (1986).

Wang, B. et al. Universal phase diagram of superconductivity and charge density wave versus high hydrostatic pressure in pure and Se-doped 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 97, 220504 (2018).

Ueno, K. Introduction to the growth of bulk single crystals of two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenides. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 84, 121015 (2015).

Moll, P. J. Focused ion beam microstructuring of quantum matter. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 9, 147–162 (2018).

dos Reis, R. D. et al. On the search for the chiral anomaly in Weyl semimetals: the negative longitudinal magnetoresistance. N. J. Phys. 18, 085006 (2016).

Bovet, M. et al. Interplane coupling in the quasi-two-dimensional 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 67, 125105 (2003).

Darancet, P., Millis, A. J. & Marianetti, C. A. Three-dimensional metallic and two-dimensional insulating behavior in octahedral tantalum dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 90, 045134 (2014).

Ritschel, T. et al. Orbital textures and charge density waves in transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Phys. 11, 328–331 (2015).

Ngankeu, A. S. et al. Quasi-one-dimensional metallic band dispersion in the commensurate charge density wave of 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 195147 (2017).

Yu, X. L. et al. Electronic correlation effects and orbital density wave in the layered compound 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 125138 (2017).

Tanda, S., Sambongi, T., Tani., T. & Tanaka, S. X-ray study of charge density wave structure in 1T-TaS2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 53, 476–479 (1984).

Kézsmárki, I. et al. Separation of orbital contributions to the optical conductivity of BaVS3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 186402 (2006).

Wu, X. L. & Lieber, C. M. Direct observation of growth and melting of the hexagonal-domain charge-density-wave phase in 1T-TaS2 by scanning tunneling microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 1150 (1990).

Ritschel, T. et al. Pressure dependence of the charge density wave in 1T-TaS2 and its relation to superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 87, 125135 (2013).

Di Salvo, F. J. & Graebner, J. E. The low temperature electrical properties of 1T-TaS2. Solid State Commun. 23, 825–828 (1977).

Gasparov, L. V. et al. Phonon anomaly at the charge ordering transition in 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 66, 094301 (2002).

Fox, M. Optical properties of solids. (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Buron, J. D. et al. Electrically continuous graphene from single crystal copper verified by terahertz conductance spectroscopy and micro four-point probe. Nano Lett. 14, 6348–6355 (2014).

Cocker, T. L. et al. Microscopic origin of the drude-smith model. Phys. Rev. B 96, 205439 (2017).

Basov, D. N., Timusk, T., Barakat, F., Greedan, J. & Grushko, B. Anisotropic optical conductivity of decagonal quasicrystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 1937 (1994).

Martin, S., Hebard, A. F., Kortan, A. R. & Thiel, F. A. Transport properties of Al65Cu15Co20 and Al70Ni15Co15 decagonal quasicrystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 719 (1991).

Dardel, B., Grioni, M., Malterre, D., Weibel, P. & Baer, Y. Temperature-dependent pseudogap and electron localization in 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 45, 1462 (1992).

Torikachvili, M. S., Kim, S. K., Colombier, E., Bud’ko, S. L. & Canfield, P. C. Solidification and loss of hydrostaticity in liquid media used for pressure measurements. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 86, 123904 (2015).

Dyadkin, V., Pattison, P., Dmitriev, V. & Chernyshov, D. A new multipurpose diffractometer PILATUS@SNBL. J. Synchrotron Rad. 23, 825–829 (2016).

Syassen, K. Ruby under pressure. High. Press. Res 28, 75–126 (2008).

Petříček, V., Dušek, M. & Palatinus, L. Crystallographic computing system JANA2006: general features. Z. Kristallogr. Cryst. Mater. 229, 345–352 (2014).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Dal Corso, A. Pseudopotentials periodic table: from H to Pu. Comput. Mater. Sci. 95, 337–350 (2014).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Marzari, N., Vanderbilt, D., De Vita, A. & Payne, M. C. Thermal contraction and disordering of the Al(110) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 3296 (1999).

Cococcioni, M. & de Gironcoli, S. Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the LDA+U method. Phys. Rev. B 71, 35105 (2005).

Cho, D. et al. Correlated electronic states at domain walls of a Mott-charge-density-wave insulator 1T-TaS2. Nat. Commun. 8, 392 (2017).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Timrov, I., Marzari, N. & Cococcioni, M. Hubbard parameters from density-functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 98, 085127 (2018).

Shishkin, M. et al. Self-consistent parametrization of DFT+U framework using linear response approach: application to evaluation of redox potentials of battery cathodes. Phys. Rev. B 93, 085135 (2016).

Ricca, C. et al. Self-consistent site-dependent DFT+U study of stoichiometric and defective SrMnO3. Phys. Rev. B 99, 094102 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express gratitude to Dr. Tobias Ritschel (TU Dresden), professor Philipp Aebi (University of Fribourg), Dr. Nicholas Ubrig (University of Geneva) and professor Dr. Andrew Mackenzie (MPI CPfS Dresden) for valuable discussions and feedback, as well as Dr. Gaetan Giriat (EPFL) for the instrumentation related support and Dr. Maja Bachmann (MPI CPfS Dresden) for her assistance with FIB microfabrication. We also appreciate the allocation of the beamtime at the Swiss–Norwegian Beam Lines (SNBL) by the SNX council and thank Dr. Vladimir Dmitriev and the BM01 staff for their support and assistance during the X-ray diffraction experiments. This study has been funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation through its SINERGIA network MPBH and grant No. 200021_175836. The work by I.B. was supported in part by Croatian Science Foundation Project No. IP-2018-01-7828. The work by E.T. was supported in part by Croatian Science Foundation Project No. IP-2016-06-7258. A. Akrap acknowledges funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation through Project No. PP00P2_170544. C.P. and P.J.W.M. acknowledge the support from the Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.M. and K.S. performed a part of the FIB microfabrication, prepared and conducted resistivity measurements at ambient and high pressures, analysed the resistivity data and wrote the manuscript. A.P. performed the early iterations of FIB microfabrication and together with L.C prepared and conducted the first resistivity measurements at ambient and high pressures. I.B and E.T. performed the DFT calculations and provided a theoretical support. C.P. performed a part of the FIB microfabrication and together with P.J.W.M. provided a FIB-related expertise. The X-ray diffraction experiments were conducted by A. Arakcheeva and L.C. and the gathered data were analysed by A. Arakcheeva. A. Akrap advised on various aspects of the work and helped with the manuscript preparation. H.B. synthesised the single crystals of 1T-TaS2. The idea behind the study was conceived by L.F., who also headed the laboratory hosting the study. The project was supervised by L.F. and K.S.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martino, E., Pisoni, A., Ćirić, L. et al. Preferential out-of-plane conduction and quasi-one-dimensional electronic states in layered 1T-TaS2. npj 2D Mater Appl 4, 7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-020-0145-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-020-0145-z

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Dualistic insulator states in 1T-TaS2 crystals

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Charge density wave surface reconstruction in a van der Waals layered material

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Unidirectional Kondo scattering in layered NbS2

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2021)

-

Uniaxial strain-induced phase transition in the 2D topological semimetal IrTe2

Communications Materials (2021)

-

Quantum phases and spin liquid properties of 1T-TaS2

npj Quantum Materials (2021)