Abstract

The first-passage-time (FPT) that a tumor size reaches a particular barrier is important in evaluating the efficacy of anti-cancer therapies and understanding certain oncological time occurrences. For certain verified stochastic models describing the volume of a tumor, a moving barrier for the tumor size in which an explicit solution of an FPT probability density function (PDF) exists for the first time the tumor size reaches the moving barrier is obtained in this work. The stochastic tumor dynamics incorporate anti-cancer therapies/treatments that are administered at varying rates. The first-passage-time density (FPTD) is derived and utilized to determine the time at which the tumor volume first reaches the moving barrier, providing a framework for analyzing various oncological time metrics. These metrics include key time measurements used to characterize tumor progression, evaluate treatment response, and capture recurrence patterns in cancer dynamics. The treatment effort needed to cause reduction in tumor size is also obtained. We obtained, for a tumor growing initially, the FPTD for the random variables describing the first time that the growth of the tumor starts slowing down following the commencement of treatment, the first time that the tumor starts showing signs of shrinkage after the start of treatment, the first time it takes for the reduction in tumor to start slowing down, and the first time for tumor recurrence after partial remission. This work is applied to experimental data including the Murine Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells originally derived from a spontaneous tumor in twenty control mice. The time at which the volume of the tumor of each mouse doubles in size is estimated using the results obtained in this study. Additionally, tumor volume experiments conducted on another eight control mice are used to validate the findings derived in this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stochastic models play a crucial role in understanding the random nature of tumor growth and therapy resistance, providing deeper insights into the evolutionary dynamics of tumors. These models are essential in capturing tumor cell population heterogeneity, accounting for random mutations, and simulating the stochastic effects of the tumor microenvironment. By incorporating stochastic dynamics, researchers can better predict treatment responses and optimize cancer therapies.

Tumor growth is influenced by multiple random factors, including cell mutation, cell division, genetic drift, and random interactions within the tumor microenvironment. The growth dynamics of individual cells in early tumor development are subject to genetic mutations and stochastic fluctuations that cannot be precisely predicted. These mutations can significantly alter proliferation rates or drug resistance in specific tumor cells, resulting in substantial variability in tumor growth. A defining characteristic of cancer is the heterogeneity of tumor cells, where individual cells within the same tumor exhibit different growth rates, drug responses, and therapy resistances. This heterogeneity arises from stochastic processes such as random mutations, epigenetic modifications, and unpredictable interactions between cells and their microenvironment.

Albano et al.1 highlighted the discrepancies between clinical data and theoretical predictions due to varying environmental fluctuations, emphasizing that ignoring such fluctuations can lead to inadequate therapies. Gatenby et al.2,3 further discuss how genetic instability and random mutations contribute to intra-tumor heterogeneity, making tumor growth and therapy resistance unpredictable. The heterogeneity and evolutionary adaptability of tumor cell populations necessitate treatment strategies that account for the stochastic nature of cancer progression. The emergence of drug resistance is a stochastic process, wherein random mutations grant survival advantages to select cells. These resistant cells proliferate, ultimately causing treatment failure. Understanding these random dynamics is crucial for developing strategies to prevent or delay resistance. Since deterministic models often fail to capture the inherent probabilistic nature of these systems, stochastic models provide a more realistic and detailed framework for describing biological phenomena.

The timing of the first tumor remission or reduction is critical for understanding cancer behavior, particularly in relation to cancer stem cells (CSCs). CSCs represent a small population of tumor cells with self-renewal and differentiation properties, contributing to tumor initiation, progression, relapse, and metastasis. Time to Response (TTR) quantifies the duration required for the tumor to show signs of shrinkage after treatment initiation. A Partial Response (PR)4 is typically defined as a significant reduction (usually at least \(30\%\)) in tumor size, as measured through imaging techniques such as CT scans, MRI, or PET scans. When cancer enters remission, the majority of rapidly dividing tumor cells may be eradicated, yet CSCs might persist. This persistence explains why tumors may shrink temporarily but still have the potential to recur if CSCs are not entirely eliminated. A short remission period suggests that CSCs were not effectively targeted or removed by treatment, whereas an extended remission period indicates either a successful therapy in controlling CSCs or a reduced ability of the remaining CSCs to repopulate the tumor. However, many cancers exhibit a tendency to relapse years after remission, particularly if dormant CSCs become reactivated.

Cancer remission time is typically defined as the period during which cancer symptoms are reduced or remain stable. While remission is often associated with a specific timeframe (usually at least one month), the exact timeline depends on the cancer type and treatment protocol. Remission duration serves as a key marker for evaluating treatment success, assessing relapse risks, and guiding personalized follow-up care. A complete remission is achieved when treatment effectively eliminates detectable cancer cells, confirmed through imaging, blood work, or biopsies. Conversely, recurrence or relapse occurs when cancer returns after a disease-free or partial remission period, often due to the survival and subsequent growth of CSCs or resistant tumor cells under favorable conditions.

Assessing the effects of cancer treatment is a critical clinical necessity for evaluating remission occurrence in cancer patients. These assessments aid in understanding tumor growth delay and optimizing treatment schedules. Several methods1,5,6,7,8 have been proposed to evaluate these measures. One approach involves calculating tumor doubling time (DT) or half-life (THL), which represent the time required for a tumor to double or reduce to half its original size, respectively. In deterministic models, a shorter DT signifies faster tumor growth. In stochastic models, where tumor dynamics follow stochastic processes, the calculation of DT and THL is extended to determine the expected first time a tumor reaches a particular barrier.

A First Passage Time (FPT) model can effectively describe the time required for a tumor to shrink under treatment, offering insights into the timeframe for remission occurrence. Cancer progression and remission are inherently stochastic processes, where tumor growth or shrinkage is random. FPT models predict when a tumor is likely to reach a specific size or remission threshold while accounting for variability in tumor response to treatment. These models provide valuable clinical insights for designing personalized cancer treatment plans, optimizing therapeutic strategies to maximize remission duration, and minimizing recurrence risks. Several mathematical and statistical methods5,6,7,9,10 have been developed to calculate the first time

a stochastic process X(t) reaches a moving barrier S(t), starting from \(x_{0}\). In tumor dynamics, the moving barrier S(t) can be thought of as a threshold of tumor size or a critical number of mutations that a tumor must overcome to transition into a more aggressive or resistant state. The tumor cells might reach this critical size or threshold at different times due to random growth rates and mutations. As the tumor grows, it is effectively moving toward a barrier which is also evolving with time due to external factors like treatment, immune response, or tumor micro-environment changes. Let \(g(S(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})\), \(f(x(t),t|x_{0},t_0)\), and \(F(x(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})\) be the first passage time density function (FPTD), the transition, and the cumulative probability distribution of the process X(t) at time t, respectively. According to the work of Jáimez11, the FPT p.d.f. \(g(S(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})\) for one-dimensional time-homogeneous diffusion process through varying boundary S(t) satisfies a new Volterra integral of the second kind

where

\(A_{1}(x,t)\) and \(A_{2}(x,t)\) are the drift and infinitesimal variance of X(t), respectively. The theory of first-exit times was used in the work of Tuckwell12 to obtain differential equations for the moments of the first-passage time (FPT) of a Markov process to a barrier S(t). The dynamics of the finite moments \(M_{n}(x,y)=E[T^{n}(x,y)]\) (of order \(n\le n_{0}\)) of the first passage time \(T(x,y)=\inf \{t\ | \ x(t)=S(t)\ |\ X(0)=x<y=S(0)\}\) the process x(t) (satisfying the stochastic differential equation with drift and infinitesimal variance \(A_{1}(x)\) and \(A_{2}(x)\), respectively,) first hits the moving barrier S(t) satisfying the scalar ordinary differential equation \(\frac{dS}{dt}=\gamma (S),\ \ S(0)=y\) were obtained to satisfy a recursion system of equations. The problem with this method is getting the appropriate boundary condition satisfying the recursion system.

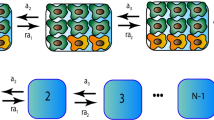

Several tumor models (with treatments administered at a constant rate) were considered in the work of Otunuga13. These models were used to capture the path of the volume of breast cancer obtained by orthotopically implanting LM2-\(4^{LUC+}\) cells into the right inguinal mammary fat pads of 6-to 8-week-old female SCID (Severe Combined Immuno-Deficient) mice. It was shown that the models demonstrated excellent goodness-of-fit in all the tumor specimens considered. In this work, we extend the models to include varying treatment rates and study the first-passage time the volume of the tumor first reaches a certain moving barrier. The moving barrier could represent immune system dynamics, which may become more aggressive or less effective, or the changing nature of drug resistance in the tumor cells. In the case of therapy, tumor’s growth rate or dynamics can be modified due to therapies, effectively shifting the barrier in a time-dependent manner. The moving barrier S(t) in this sense could represent how therapies, such as drug doses, alter the critical point at which the tumor’s progression transitions to a more aggressive form, or when resistance arises. The moving tumor barrier upon which an explicit FPTD distribution exists is also derived in this work. Formulas and procedures for calculating the distribution of the first time that the growth of the tumor starts slowing down after the start of treatment, the first time that the tumor starts showing signs of shrinkage after the start of treatment, the first time it takes for the reduction in tumor to start slowing down, and the first time for tumor recurrence are obtained in this work. The average age of the tumor when it first reaches the moving barrier S(t) is also obtained.

The remainder of this paper is set out as follows. We first obtain and analyze the distribution of the age that a tumor with volume satisfying a generalized stochastic Gompertz dynamic first reaches a moving barrier. The moving barrier S(t) for which the closed form FPTD exist is also derived. In the presence of treatment, we consider the volume of a tumor satisfying a stochastic Gompertz model with a varying treatment rate. This is used to obtain the distribution of the age the tumor reaches a moving barrier. The FPTD provides insights into the effectiveness of interventions. It is also used to calculate the first recurrence time of the tumor after a partial remission, which can help in optimizing follow-up schedules and maintenance therapy. The result is used to analyze how long the tumor responds to treatment before resistance occurs, and in estimating the duration of chemotherapy effectiveness. The minimum amount of treatment needed to cause reduction in tumor size average is also obtained. For tumor volumes satisfying generalized stochastic logistic models with varying treatments, the expected time that the volume first reaches a certain barrier is calculated. A similar work with a modified stochastic model is discussed in a later section. A major contribution of this work lies in obtaining a closed-form expression for the FPTD for the first time a tumor size reaches a moving barrier. The work done here is applied to experimental data, with conclusion given in the last section.

Methods

The FPT distribution plays a crucial role in modeling and understanding tumor growth dynamics, particularly in predicting critical transitions such as the time required for a tumor to reach a detectable size, invade surrounding tissues, or respond to treatment. Since tumor progression is inherently stochastic, FPT provides a powerful mathematical and statistical framework for studying these random processes in oncology. Obtaining closed-form expressions for First Passage Time distributions and barriers are vital for understanding tumor growth, optimizing detection strategies, predicting treatment outcomes, and improving computational efficiency. By integrating these solutions into clinical decision-making, researchers can advance personalized cancer treatment and enhance early diagnosis, ultimately improving patient outcomes. In this section, we obtain results for the FPTD density for the first time a tumor size reaches some biological realities (moving barriers) where the threshold for tumor progression or treatment failure is not static. Unlike a constant barrier, the importance of obtaining a closed expression for moving barriers is more emphasized in the capturing treatment-induced resistance and relapse, and in improving predictions for metastasis timing. It accounts for increasing resistance thresholds, where more resistant cells require higher drug doses to be controlled. It also helps in predicting delayed relapse prediction, since tumors may shrink initially but later rebound when resistance crosses a critical level. In targeted therapy, resistance barriers increase as mutated cells evade drug action. A constant barrier would fail to capture this gradual resistance buildup.

In the early stages of tumor development, tumor grows exponentially, doubling in size in a very short amount of time. Both Gompertz and logistic models capture this rapid growth, but the Gompertz model allows for more realistic early growth because its exponential component reflects a rapid increase in growth in the initial phase, followed by a rapid deceleration. To obtain closed form expression for the moving barriers and FPTD, we consider stochastic models following different variants of generalized logistic and Gompertz models in the following sections.

Distribution of tumor age with volume satisfying generalized Gompertz dynamic

A tumor behavior, where the growth rate initially accelerates and then slows as resources (like nutrients, blood flow, and oxygen) become limited and the tumor reaches a limiting constant value follows the description of the Gompertz model with the property that growth is slowest at the start and end of a given period, with the growth at the end approached much more gradually than the starting time. In the absence of treatment, a stochastic analog of the generalized Gompertz model due to the effects of toxicants on a population in a random environment was developed in the work of Otunuga13 to follow the equation

using the Stratonovich calculus, where \(c> 0\) is the shape parameter, and W(t) is a Wiener process, a standard Brownian motion. With an appropriate value for the shape parameter c, the Gompertz model (3) is appropriate to measure the volume of tumor undergoing spontaneous remission, a rare phenomenon where a tumor shrinks or disappears without any treatment. In the drift part \(r x\left( \log \varvec{\mathcal {K}}-\log x\right) ^{c}\), the case \(c=1\) describes the standard Gompertz growth. If \(c>1\) however, the growth rate slows down much faster as the tumor size approaches its carrying capacity. If \(c<1\), the growth rate decays more slowly, allowing the tumor to grow larger before growth suppression kicks in. The noise term \(\sigma x\left( \log \varvec{\mathcal {K}}-\log x\right) ^{c}\circ dW(t)\) captures the high uncertainty in tumor growth during early stages. This uncertainty may arise from factors such as competition among different subpopulations of cancer cells for limited resources, immune responses where the immune system recognizes and attacks the tumor, or dynamic changes within the tumor microenvironment that influence tumor growth and regression. The parameter c acts as a stochastic growth dampener or amplifier. In higher c settings, tumors stabilize quickly with less chance of recurrence, while in lower settings, tumors exhibit persistent stochastic fluctuations, increasing recurrence or uncontrolled growth. Here, we aim to study the first-passage time (FPT) that a population or tumor size first reaches a certain size, or to calculate the age of the tumor size.

For some arbitrary continuous barrier S(t), let

be the FPT of the process x(t) through the boundary S(t), and let \(g(S(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})\) be the corresponding first passage time probability density function. Also, let \(f(x,t|x_{0},t_{0})\) be the transition probability density function for the process x(t) at time t with initial value \(x_{0}\). Here, the drift and the infinitesimal variance \(A_{1}(x,t)\) and \(A_{2}(x,t)\) are given by

respectively, for \(c\ge 1\). The transition PDF \(f(x,t|x_{0},t_{0})\) is obtained as

where \(\Phi (x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi }}\int _{-\infty }^{x}e^{-\frac{z^{2}}{2}}dz\) is the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the standard normal distribution. Assuming \(S(t)\in C^{2}(t_{0},+\infty )\), the moving barrier S(t) can be obtained from the equation

where \(\psi (S(t),t|y,\tau )\) satisfies equation (2) and the functions \(A_{i}(x,t)\), \(i=1,2\), and \(f(x,t|x_{0},t_{0})\) are obtained in (5) and (6), respectively. The general solution S(t) satisfying the ordinary differential equation

is obtained as

for some constants \(M\in \mathbb {R}\), \(Q_{1}\ge 0\). It can be shown that \(\lim \limits _{c\rightarrow 1}\mathcal {K}\exp \left( -\left( M^{1-c}+Q_{1}(1-c)(t-t_{0})\right) ^{\frac{1}{1-c}}\right) =\mathcal {K}\exp \left( -Me^{Q_{1}t}\right)\).

Significance of the moving barrier S(t)

In oncology, an exponentially growing barrier in the absence of treatment can represent an increasing resistance threshold to immune system or a growing tumor control threshold due to mutations. On the other hand, a decaying barrier can represent the shrinking threshold for tumor remission due to the influence of the immune system in the absence of treatment.

Theorem 1

The first time that a tumor with volume x(t) satisfying (3) reaches the barrier S(t) follows the probability density function

The average first time the tumor reaches the barrier S(t) is obtained as

with average age calculated as \(\mathbb {E}\left[ \tau _{X}^{S(t)}|x_{0}\right] -t_{0}\).

Proof

Following the work of Jáimez et al.11, the Volterra integral equation (1) reduces to

where \(\psi (S(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})\) is as defined in (2). The FPTD (9) follows by substituting (5), (6), and (8) into (2). The mean age is calculated by evaluating \(\int _{t_{0}}^{\infty }t\,g(S(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})\,dt-t_{0}\). \(\square\)

Figure 1a shows a single sample path of the tumor volume x(t) satisfying (3) together with the barrier S(t) in (8) for the case \(c=1.2\) and the first passage time the tumor size reaches the barrier S(t). Here, \(\mathcal {K}=e^{1}\), intrinsic growth rate \(r=1\), \(x_{0}=1.5\), and noise intensity \(\sigma =0.3\). Using the same parameters, the graph of the histogram of the first passage time \(\tau _{X}^{S(t)}\) and the probability density function \(g(S(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})\) of the first passage time the process x(t) reaches the barrier \(S(t)=\mathcal {K}\exp \left( -\left( M^{1-c}+Q_{1}(1-c)(t-t_{0})\right) ^{\frac{1}{1-c}}\right)\) is shown in Fig. 1b using \(M=\log \frac{\mathcal {K}}{S_{0}}\), \(Q_{1}=0.5r/(1-c)\), \(S(t_{0})=S_{0}=\mathcal {K}/3\). To verify the validity of the FPTD \(g(S(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})\), we plot the histogram of the first time the sample path \(\{x^{l}(t_{j})\}_{j=1}^{N}\) (derived by discretizing (3) using Milstein scheme) first reaches the moving barrier \(\{S(t_{j})\}_{j=1}^{N}\), for \(l=1,2,\cdots ,L\) simulations, with \(L=70,000\) simulations and \(N=5,000\) sample points. In the absence of treatment, the first passage time density analysis on an exponentially growing barrier in oncology provides insights into the natural progression and aggressive behavior of untreated tumors. In this context, the exponentially growing barrier represents the natural unchecked growth of the tumor size threshold (often driven by cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, or metastatic spread) in the absence of treatment. In some cancers, especially aggressive tumors, the tumor may develop immune evasion mechanisms allowing unchecked growth. The barrier S(t) in that case may represent the rapidly growing tumor size threshold under immune evasion or accelerated proliferation.

A special case of (8) is the case where \(M=\ln \frac{K}{x_{0}}\) and \(Q_{1}=-r\). For this case, the barrier S(t) describes the tumor volume in the absence of noise. That is, the solution of the deterministic equivalent

of (3) derived by setting \(\sigma =0\).

Another special case of (8) can be derived by setting \(Q_{1}=0\) and \(M=\ln \frac{2K}{x_{0}}\) and \(M=\ln \frac{K}{2x_{0}}\). In this case, S(t) reduces to half or twice the initial volume size.

We calculate the distribution and expectation of the age that x(t) first reaches the size \(S_{0}\) in Theorem 2 below.

Theorem 2

The age that a tumor with volume x(t) satisfying (3) first reaches the size \(S_{0}\) follows the probability density function

The mean age is obtained as

Proof

The proof follows by setting \(S(t)=S_{0}\) and evaluating \(g(S_{0},t|x_{0},t_{0})\). \(\square\)

Doubling time

The distribution of the first time a tumor size doubles in initial size can be calculated using (13) by setting \(S_{0}=2x_{0}\). In this case, the doubling time FTPD is

Distribution of tumor age with volume size satisfying Gompertz model with treatment

The generalized stochastic Gompertz model (3) describes the natural growth of a tumor, without taking into account the impact of therapies like chemotherapy, radiation, or immunotherapy. Adding treatment terms allows the model to reflect more realistic tumor dynamics, making it possible to predict the effectiveness of a given treatment over time. Incorporating treatments into the model allows for the calculation of the time it takes for therapies to alter the tumor growth dynamics. In the presence of treatment administered at regular time period, we consider the stochastic Gompertz model describing a tumor with volume size \(x(t)\in (0,\infty )\) satisfying

where the anti-tumor treatment/therapy rate is assumed to be proportional to the size of the tumor, with time-varying tumor harvesting effort function E(t) that measures the treatment efficacy/intensity at a given time t. A similar model is discussed in the work of Otunuga13 (with constant rate E) and Albano et al.14,15.

Several models16,17,18,19have been developed to describe the effects of treatment in eradicating or slowing tumor growth. Chemo-kinetic models focus on the time-dependent dynamics of drug concentrations and their effects on tumor cells. These models incorporate pharmacokinetics16-how drugs are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and eliminated-and pharmacodynamics, which describes their impact on tumor cells over time. In cancer immunotherapy, the generalized exponential power function-the product of an exponential decay and a power function-can effectively model the behavior of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T (CAR-T) cells. CAR-T cells, genetically engineered to target cancer cells, undergo an initial expansion phase followed by a decline due to factors like exhaustion, differentiation, or immune suppression. This dynamic can be captured by the function: \(E(t) = e^{-\lambda t} t^n\), where the power term (\(t^n\)) describes the rapid expansion of CAR-T cells, and the exponential decay (\(e^{-\lambda t}\)) represents their decline. If tumor harvesting occurs at a constant rate, the drug concentration E(t) follows: \(\frac{dE}{dt} = \kappa _1\), where \(\kappa _1\) represents the infusion rate. Assuming uniform drug distribution, the concentration can be modeled by an exponential decay: \(\frac{dE}{dt} = -\kappa _e E(t)\), where \(\kappa _e\) is the drug elimination rate constant. When continuous infusion is considered, this extends to \(\frac{dE}{dt} = \kappa _1 - \kappa _e E(t)\), where \(\kappa _1\) is the infusion rate. To account for drug resistance, the model can be further modified as: \(\frac{dE}{dt} = -(\kappa _e + \kappa _a)E(t) + \kappa _r E_{\text {infusion}}(t)\), where \(\kappa _e\) and \(\kappa _a\) represent elimination and absorption rates, and \(\kappa _r\)characterizes the rate of resistance development. Other PK-PD (pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic) models18,19 incorporate more complex interactions between drug concentration and tumor response. In cases where drug elimination becomes saturable, particularly at high doses or when enzymatic metabolism is limited, the concentration follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics:\(\frac{dE}{dt} = -r \frac{E(t)}{\kappa _m + E(t)}\), where r represents the maximum drug metabolism rate. These models provide crucial insights into optimizing drug delivery, improving treatment efficacy, and understanding tumor response to therapy.

In the presence of treatment, the model (16) can be re-written in the Itô form

where

The solution of (17), obtained as

has a log-normal distribution with mean \(\mu _{X}(t)=\mathbb {E}\left[ x(t)|x_{0}\right]\) and median=\(m_{d}(t)\) satisfying

where

Since \(x(t)>0\) a.s., the process

satisfies

Let

be the first passage time (FPT) of the process V through a moving barrier H(t), and let \(g_{V}(H(t),t|V_{0},t_{0})\) be the corresponding first passage time probability density function. Define

Since the logarithmic function is continuous and invertible on the positive real line, it follows that

corresponds to the first passage time of the process x(t) through the boundary S(t) in (21). The probability density function for the FPT \(\tau ^{S(t)}_{X}\) of x(t) through the boundary S(t), denoted by \(g_{X}(t|x_{0},t_{0})\), can be calculated to be the same as \(g_{V}(H(t),t|v_{0},t_{0})\). Define

The transition probability density function of the process V(t) is obtained as

The moving barrier H(t) for which an explicit solution \(g_{V}(H(t),t|v_{0},t_{0})\) exists satisfies the ordinary differential equation

with general solution

where A is a constant. Using (11), the FPT p.d.f. of the process V(t) through the boundary H(t) is obtained as

Using (21), (22), and (24), the moving barrier S(t) is obtained as

and the first-passage-time probability density function

Sample paths for tumor size satisfying (16) with different treatment concentrations: Itô Form.

Figure 2 shows the graph of three sample paths for a tumor size satisfying (16) with different tumor harvesting efforts \(E(t)=E\), \(E(t)=t^{3/2}e^{-t/4}\), and \(E(t)=e^{-(t-1)^{2}}\) using the parameters: \(\mathcal {K}=e^{3}\), \(E=e^{1}/7\), \(r=1\), \(x_{0}=1.5\), and \(\sigma =0.1\). The graphs show the effect of different tumor harvesting effort E(t) on the growth of a tumor with size satisfying a stochastic Gompertz model.

Constant tumor harvesting effort

In this case, \(E(t)=E\) is the same at any given time, the tumor barrier S(t) and the explicit FPT p.d.f. \(g_{X}(t|x_{0},t_{0})\) reduce to

and

respectively, for some arbitrary constants A and B.

Case 1: significance of barrier S(t) if harvesting effort is constant overtime and \(A=B=0\)

In this case, E(t) is a constant and

is a constant and \(A=B=0\). The boundary H(t) in (28) reduces to \(H(t)=\mu\) and the FPT becomes the first passage time \(\tau ^{\mu }_{V}\) the process V(t) reaches the mean level \(\mu\) of the log tumor volume. Using (22), the barrier

is the equilibrium where the effects of the tumor growth and treatment balance each other. It represents the limiting median process \(\lim \limits _{t\rightarrow \infty }m_{d}(t)\) as defined in (18). Median tumor size is commonly used to classify patients into risk categories. Studies often correlate median tumor size with survival rates-patients, where those with tumors above the median size tend to have lower survival probabilities compared to those below the median. It follows from (22) that the PDF \(g_{X}(t|x_{0},t_{0})\) of the FPT of the process x(t) through the boundary S(t) is

The mean time that the tumor first reaches the size \(e^{\mu }\) is calculated in Theorem 3.

Theorem 3

If treatment intensity/harvesting effort E(t) is constant at any given time, the tumor with size x(t) satisfying (16) has a mean age

by the first time it reaches the expected initial size \(e^{\mu }\), where \(\text{ Erfi }(x)=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi }}\int _{0}^{x} e^{z^{2}}dz\) and \({_2F_{2}}\left( a,b;x\right)\)is the hypergeometric function20. Furthermore, this time has the distribution given in (31).

Proof

The first-passage time distribution for the first time the process x(t) reaches the barrier \(e^{\mu }\) is obtained from (29) by setting \(A=B=0\). The expected time \(\mathbb {E}[\tau _{X}^{e^{\mu }}|x_{0}]=\mathbb {E}_{x_{0}}[\tau _{X}^{e^{\mu }}]\) the process x(t) first reaches the level \(e^{\mu }\) is

\(\square\)

Figure 3a shows a sample path of the volume x(t) together with the barrier \(e^{\mu }\) and the first passage time the process x(t) crosses the barrier \(e^{\mu }\). Here, it is assumed that the tumor harvesting effort \(E(t)=E\) is a constant, and \(\mathcal {K}=e^{1}\), tumor harvesting effort \(E=e^{1}/5\), intrinsic growth rate \(r=1\), \(x_{0}=1\), and noise intensity \(\sigma =0.1\). Using the same parameters, the graph of the histogram of the first passage time \(\tau _{X}\) and the probability density function \(g_{X}(t|x_{0},t_{0})\) of the first passage time the process x(t) reaches the barrier is shown in Fig. 3b. The constant E serves as the treatment intensity (or chemotherapy) administered in the presence of noise. The barrier S(t) serves as the limiting median tumor size after treatment.

Table 1 shows a comparison of simulated mean first passage time (MFPT) and the exact MFPT obtained in (32). The simulated MFPT is calculated by first discretizing the stochastic model (17) in the time interval [0, 15] using the Milstein scheme

where \(x_{j}^{l}=x^{l}(t_{j})\), \(\Delta W^{l}_{j+1}=W^{l}(t_{j+1})-W^{l}(t_{j})\), \(t_{j}=j\Delta t\), \(\Delta t=(15-0)/N\), \(j=1,2,\cdots ,N\) for sample size N, \(l=1,2,\cdots ,L\) for L simulations. For considerable large sample size N and large number of simulations L, the first time, \(\tau _{X}^{l}\), the process \(\left\{ x^{l}(t_{j})\right\} _{j=1}^{N}\) first reaches the barrier \(S(t)=e^{\mu }\) is calculated for \(l=1,2,\cdots ,L\). The mean of the vector \(\left\{ \tau _{X}^{l}\right\} _{l=1}^{L}\) is now calculated as the estimated MFPT in Table 1.

The parameters used to generate Table 1 are \(r=1\), \(K=e^{1}\), \(E=b/5\), \(\sigma =0.1\), \(x_{0}=1\), \(S=e^{\mu }\).

Case 2: significance of barrier S(t) if tumor is harvested at a constant rate and \(B=0\)

If E(t) is a constant, E, so that \(\mu (t)\equiv \mu\) is a constant and \(B=0\), then the moving barrier H(t) reduces to

where \(A=H(t_{0})-\mu\). For the case where \(H(t_{0})=v_{0}\), it follows from (18) that the moving barrier S(t) reduces to the median \(S(t)=m_{d}(t)\) of the tumor growth x(t). Knowledge of the median of a tumor growth in a given patient population helps clinicians make informed decisions regarding treatment plans, deciding whether to consider a more aggressive or alternative treatments if a patient’s tumor grows faster than the median. This barrier can also represent the Treatment-Induced tumor shrinkage limits, a residual disease where treatment is effective but cannot eliminate all cancer cells, leaving behind a stable minimal residual tumor. It follows from (22) that the first time the tumor size reaches the moving median size has the probability density function

Theorem 4

If the tumor harvesting effort E(t) is a constant E, the tumor with size x(t) satisfying (16) has a mean age

by the first time it reaches the moving barrier \(S(t)=\exp \left( \mu + (H_{0}-\mu )e^{-r(t-t_{0})}\right)\). Furthermore, this time has a distribution given in (34).

Proof

The first-passage time distribution for the first time the process x(t) reaches the barrier S(t) is obtained from (29) by setting \(B=0\). The expected time \(\mathbb {E}_{x_{0}}[\tau ^{S(t)}]\) the process x(t) first reaches the level \(e^{\mu +(H_{0}-\mu )e^{-r(t-t_{0})}}\) is

\(\square\)

Figure 4a shows a sample path of the process x(t) together with the barrier \({S(t)}=\exp \Big( \mu + \left( H(t_{0})-\right. \)\(\left. \left.\mu \right) e^{-r(t-t_{0})}\right)\), the expected tumor volume size, \(\mu _{X}(t)\), and the first passage time the sample path process x(t) crosses the barrier. Here, \(\mathcal {K}=e^{1}\), treatment effort \(E=e^{1}/5\), intrinsic growth rate \(r=1\), \(x_{0}=1.5\), \(H_{0}=\log (1.8)\), and noise intensity 0.1. Using the same parameters, the graph of the histogram of the first passage time \(\tau _{X}^{S(t)}\) and the probability density function of the first passage time \(g_{X}(t|x_{0},t_{0})\) are shown in Fig. 4b. The constant E serves as the treatment effort.

Figure 5 is similar to Fig. 4 with the exception that the amount \(E=K/4\) of treatment administered, is high enough to cause a decrease in the average tumor volume as explained in (38).

Case 3: case where treatment is administered with treatment intensity \(E(t)=Lt\)

where

and \(Z(t,t_{0})\), \(Y(t,V_{0},t_{0})\), and \(\Sigma (t,t_{0})\) are given in (23), with H(t) in (24) and with \(E(t)=Lt\).

Appropriate treatment/therapy must be administered for the volume of the tumor to decrease in size. The tumor harvesting effort E(t) in this case is directly proportional to the time the treatment is administered. With an appropriate choice for L, the moving barrier S(t) can be described as a remission barrier. As shown in Fig. 6, the tumor is relapsing and the barrier S(t) traces a relapsing trajectory for the tumor volume. The parameters used here are similar to the parameters in Fig. 4, with the exception that \(E(t)=15t\). The barrier \(S(t)=\exp (H(t))\) is obtained from (24).

Calculating the time to response (TTR), partial response time (PRT), recurrence time (RCT), growth slowing time (GST), remission slowing time (RST), and remission time (RET)

The Time to Response (TTR) refers to the amount of time it takes for tumor to start showing signs of shrinkage or reduction in size after the start of treatment. Likewise, a Partial Response Time (PRT) is defined as the time when a significant reduction (usually at least 30%) in the size of the tumor occur. Tumor Recurrence Time (RT) is the first time after partial or complete remission when the tumor size crosses a predefined measurable threshold. We can sometimes refer to this as the Relapse Time (RET), which is the time when a tumor growth reappears after a period of response to treatment, regardless of whether the tumor was in partial or complete remission. Since the tumor size x(t) satisfying (17) is stochastic in nature, we assume TTR, RCT, and PRT are random and calculate the first passage probability density function for these random variables. To calculate the barrier for these random variables, we first calculate the first critical times \(\underline{t}_{1}>0\) and \(\overline{t}_{1}>0\) where the derivative of the expected tumor size \(\mu _{X}(t)\) in (18) changes from positive to negative and from negative to positive, respectively. According to elementary calculus, these are the times where the expected tumor size reaches a local maximum and local minimum tumor sizes, respectively. The TTR, RCT, and PRT will now be calculated as the first time \(\underline{\tau }>t_{0}\), \(\overline{\tau }>\underline{t}_{1}\), and \(\hat{\tau }>\underline{t}_{1}\) that the tumor size x(t) reaches the size \(\mu _{X}(\underline{t}_{1})\), \(\mu _{X}(\overline{t}_{1})\), and \(0.7\mu _{X}(\overline{t}_{1})\), respectively, for \(\underline{t}_{1}<\overline{t}_{1}\).

To determine when the expected tumor growth begins to slow down due to treatment effects, we calculate the corresponding time \(\underline{s}_{1}\in (0,\underline{t}_{1})\) when the second derivative, \(\mu _{X}''(t)\), of \(\mu _{X}(t)\) is zero. This point is called the point of Inflection. For \(t\ge t_{0}\), we refer to the first time that x(t) reaches the size \(\mu _{X}(\underline{s}_{1})\) as the Growth Slowing Time (GST). Likewise, treatment/therapy started to slowly become ineffective in mitigating the growth of the tumor, resulting in the slowing down of the decline in tumor growth, at the time \(\overline{s}_{1}\in (\underline{t}_{1},\overline{t}_{1})\) where \(\mu _{X}''(t)=0\). For \(t\ge \underline{t}_{1}\), we refer to the first time that x(t) reaches the size \(\mu _{X}(\overline{s}_{1})\) as the Remission Slowing Time (RST). The time it takes to achieve complete remission can vary depending on cancer type, tumor regimen, and patience response. If \(\mu _{X}'(t)<0\) for \(t\in (\underline{t}_{1},\underline{a})\), \(\underline{a}\ge \underline{t}_{1}+30\) days, then we say that the tumor is in remission.

Note that (27) is constructed for a barrier in which an explicit solution of an FTPD exist. In the case of TTR, RCT, PRT, it can be easily seen that \(\mu _{X}(\underline{t}_{1})\) and \(\mu _{X}(\overline{t}_{1})\) cannot be constructed from S(t) in (26) for any given treatment concentration. In this case, the FPTD for TTR, RCT, PRT, GST, and RST are calculated numerically from the Volterra integral equation of the second kind given in (1) as follows.

if \(v_{0}<H(t_{0})\) (the case for \(v_{0}>H(t_{0})\) can be constructed in a similar manner using (1)), where \(H(t)=\log (S(t))\), h is the time step \((T-t_{0})/N\), the interval \([t_{0},T]\) is partitioned into \(\{t_{0},t_{1}, t_{2},\cdots , t_{N}=T\}\), \(t_{k}=t_{0}+kh\), \(k=0,1,2,\cdots ,N\), \(\psi (x,t|x_{0},t_{0})\) is given in (2) with \(A_{1}\) and \(A_{2}\) derived from (19) as \(A_{1}(v,t)=r\left( \mu (t)-v\right)\), \(A_{2}(v,t)=\sigma ^{2}\), and \(g_{V}\left( t_{k}|v_{0},t_{0}\right) \equiv g_{V}\left( H(t_{k}),t_{k}|v_{0},t_{0}\right) =g_{X}\left( t_{k}|x_{0},t_{0}\right)\).

Measuring adequate treatment needed to cause tumor reduction

To measure the adequate treatment required to trigger reduction in tumor growth, we want the expected tumor volume \(\mathbb {E}[x(t)|x_{0}]\) to decrease at the time the tumor is in remission. For this to happen, the relative treatment rate E(t) must satisfy

At the time the tumor is in remission, we expect the minimum amount of treatment required to satisfy (37). In the case where treatment concentration is constant over time, the adequate treatment concentration \(\bar{E}\) must satisfy

In the following, using a treatment concentration satisfying \(E(t)=t^{3/2}e^{-t/2}\), we obtain the critical times \(\underline{t}_{1}, \overline{t}_{1},\underline{s}_{1}\) and \(\overline{s}_{1}\) where TTR, RCT, GST, and RST in the expected tumor growth first occur. The expected tumor growth and the FPTD for these random variables are plotted and compared with the exact solution obtained by numerically solving (1).

Figure 7a shows three sample paths for the tumor growth x(t) satisfying (17) for the Itô case using the parameters \(r=1\), \(K=e^{3}\), \(\sigma =0.1\), \(x_{0}=1.5\), and \(E(t)=t^{3/2}e^{-t/2}\). Figure 7b shows the expected growth size \(\mu _{X}(t)\), \(t\in [t_{0},T]\), in (18) together with the times \(\underline{s}_{1}\), \(\underline{t}_{1}\), \(\bar{s}_{1}\), and \(\overline{t}_{1}\), when tumor’s growth started to slow down, when tumor started to show signs of shrinkage (TTR), when tumor decline starts to slow down, and when recurrence in the expected tumor growth first occur, respectively. Figure 7c, d show the GST and TTR first-passage time densities \(g_{X}(t|x_{0},t_{0})\) and their histograms for the first time the tumor size \(x(t), t\ge t_{0}\), reaches the expected size \(\mu _{X}(\underline{s}_{1})\) and \(\mu _{X}(\underline{t}_{1})\), respectively. Likewise, Fig. 7e, f show the RST and RCT FPTD \(g_{X}(t|x_{0},t_{0})\) and their histograms for the first time the tumor size \(x(t), t\ge \underline{s}_{1}\), reaches the expected size \(\mu _{X}(\overline{s}_{1})\) and \(\mu _{X}(\overline{t}_{1})\), respectively. The histograms for GST and TTR are generated for the first passage time of each sample path \(\{x_{j}^{l}\equiv x^{l}(t_{j})\}_{j=1}^{N}\), where \(t_{0}=0\) and \(l=1,2,\cdots ,L\), while the histograms for RST and RCT are generated for the first passage time of each sample path \(\{x_{j}^{l}\equiv x^{l}(t_{j})\}_{j=1}^{N}\), where \(t_{0}=\underline{t}_{1}\) and \(l=1,2,\cdots ,L\). For all plots, \(N=5,000\), \(L=70,000\), \(T=6\), and \(\Delta t=(T-t_{0})/N\). The FPTD \(g_{X}(t|x_{0},t_{0})\) is calculated numerically using (36) for the appropriate domain.

Tumor age distribution with size following stochastic analogue of generalized logistic model

In this section, we consider a tumor size x(t) satisfying a stochastic analog of generalized logistic model of the form

for \(\gamma \ge -1\). The tumor dynamics (39) reduce to the Itô model

where

Case \(\gamma =-1\)

The case where \(\gamma =-1\) reduces to the scenario where the tumor volume satisfies a Geometric Brownian model of the form

Model (41) is considered for the case where \(a(t)\ne 1\). For this case, the function \(\psi (S(t),t|S(\tau ),\tau )\) and the time-dependent barrier S(t) for which the first-passage-time probability density function is explicitly obtained have been fully explored in the work of Jáimez11. It can be shown, following (7), that the barrier S(t) satisfies

for some constants A and B. Let \(\tau _{X}=\inf \{t\ge 0\,\ x(t)=S(t)\}\) be the first passage time the process x(t) reaches the barrier S(t). The first-passage-time probability density function \(g(S(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})\) is obtained as

Significance of the barrier S(t) for the case where treatment is administered at a constant rate, E

For this case, the treatment \(E(t)\equiv E\) is a constant and the expected tumor volume satisfying (41) is

With this, the barrier S(t) can be described in terms of the expected tumor volume as

Theorem 5

Provided that treatment is administered at a constant rate, E, the first time that a tumor with volume x(t) satisfying (41) reaches the barrier S(t) follows the probability density function

The tumor’s mean age at this time is

Proof

The result follows from (2) and (7), where \(A_{1}(x)=r(a-1)x\), \(A_{2}(x)=\sigma ^{2}x^{2}\), and \(g(S(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})=2|\psi (S(t),t|x_{0},t_{0})|\). \(\square\)

Figure 8a shows a sample path of the Stratonovich Geometric brownian process x(t) satisfying (41) together with the barrier S(t) for the case where \(x_{0}=1.5\), \(A=2x_{0}\), \(B=-r(a-1)\), \(b=e^{1}\), \(r=1\), \(\sigma =0.3\), and \(E=b/5\). Figure 8b shows the first-passage-time histogram and the corresponding probability density function for the first time the tumor volume x(t) doubles in size, defined as \(S(t)=A=2x_{0}\). The tumor doubling time (TDT) provides a quantitative measure of tumor growth dynamics, where a shorter TDT indicates rapid tumor proliferation, often associated with aggressive cancer types, while a longer TDT suggests slower tumor growth, indicative of less aggressive tumors. Estimating the TDT allows clinicians to characterize tumor behavior, assess treatment response, and adjust therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes.

Similar to Fig. 8, Fig. 9a shows a sample path of the Stratonovich Geometric Brownian process x(t) satisfying (41) for the case where \(A=30\), \(B=0.7\), \(b=e^{1}\), \(r=1\), \(\sigma =0.3\), \(x_{0}=55\), and \(E=b/5\). Figure 9b are the first-passage-time histogram and probability density function, respectively, for the first time the process x(t) first reaches the barrier S(t) in (42).

Figure 10 is obtained using the parameters \(A=30\), \(B=0.2\), \(b=e^{1}\), \(r=1\), \(\sigma =0.3\), \(x_{0}=55\), \(E=2\), and the barrier S(t) in (42). As described above, if the derivative of the tumor average size \(\mu _{X}(t)=\mathbb {E}\left[ x(t)|x_{0}\right]\) is negative \(delete\) for \(t\in (\underline{t}_{1},\underline{a})\), \(\underline{a}\ge \underline{t}_{1}+30\) days, where \(\underline{t}_{1}\) is a critical point where local maximum occur, then we say that the tumor is in remission. We see from Fig. 10a that \(\mu _{X}'(t)<0\) for all time \(t>0\), so this figure describes a scenario where a tumor is in remission.

Case \(\gamma>-1\): constant treatment rate

Define

and assume

We give a theorem for the average age, \(\mathbb {E}_{x_{0}}[\tau _{X}]\), of the tumor in Theorem 6 below.

Theorem 6

If treatment is administered at a constant rate, E, the average age that a tumor with volume x(t) satisfying (39) first reaches the size \(S_{0}\) is obtained as

where

and \(M(\alpha ,\beta ;x)\) is the Kummer function20,21,22.

Proof

For \(\gamma>-1\), the process

satisfies the logistic stochastic differential equation

As shown in Appendix A, Theorem 10, the process x(t) is recurrent if and only if \(\omega>0\). It follows that the first passage time \(\tau _{X}\) of the process x(t) through the barrier \(S_{0}\) is equivalent to the first passage time \(\tau _{Z}=\inf \{t\ge 0\,\ z(t)=\theta \, S_{0}^{\gamma +1}\}\) of the process z(t) through the barrier \(\theta S_{0}^{\gamma +1}\). The mean of the first passage time, \(\tau _{Y}\), that a logistic process y(t) satisfying

reaches the level \(\epsilon>0\) is obtained in the work of Giet et al.23 as

where \((a)_{n}\) is the Pochammer function, \(q=\frac{1}{2}-\frac{\alpha _{1}}{\alpha _{3}^{2}}\), \(\rho =\frac{2\alpha _{2}}{\alpha _{3}^{2}}\). The result follows by setting \(\alpha _{1}=\beta (\omega +1)/\theta\), \(\alpha _{2}=\beta /\theta\), \(\alpha _{3}=\sigma (\gamma +1)\), \(y_{0}=z_{0}=\theta x_{0}^{\gamma +1}\), \(\epsilon =\theta S_{0}^{\gamma +1}\), and noting that \(q=-\omega /2<0\), \(\rho =1\). The result for the case where \(x_{0}>S_{0}\)also follows from23. \(\square\)

Table 2 shows a comparison of simulated mean first passage time (MFPT) and the exact MFPT obtained in (65). The simulated MFPT is calculated by first discritizing the stochastic model (40) in the time interval [0, 3] using the Milstein scheme as:

where \(x_{j}^{l}=x^{l}(t_{j})\), \(\Delta W^{l}_{j+1}=W^{l}(t_{j+1})-W^{l}(t_{j})\), \(t_{j}=j\Delta t\), \(\Delta t=(3-0)/N\), \(j=1,2,\cdots ,N\) for sample size N, \(l=1,2,\cdots ,L\) for L simulations. For considerable large sample size N and large number of simulations L, the first time, \(\tau _{X}^{l}\), the process \(\left\{ x^{l}(t_{j})\right\} _{j=1}^{N}\) first reaches the barrier \(S_{0}\) is calculated for \(l=1,2,\cdots ,L\). The mean of the vector \(\left\{ \tau _{X}^{l}\right\} _{l=1}^{L}\) is now calculated as the estimated MFPT in Table 2.

The parameters used to generate Table 2 are \(r=1\), \(\gamma =0.2\), \(b=e^{\gamma +1}\), \(E=b/5\), \(\sigma =0.3\), \(x_{0}=1.5\), \(S_{0}=1.8\).

Generalized logistic model with fluctuations in growth rate

Here, we study a special stochastic analog of the generalized logistic model of the form

As discussed in the work of Otunuga13, this model arises as a result of fluctuations in the intrinsic growth rate of the population x(t) satisfying the general deterministic logistic model of the form

The model can be re-written as

where

Let \(\tau ^{S(t)}_{X}=\inf \{t\ge 0\,\ x(t)=S(t)\}\) be the first passage time the volume of a tumor x(t) satisfying (53) reaches a moving barrier S(t). We give a theorem for the average age, \(\mathbb {E}_{x_{0}}[\tau ^{S(t)}_{X}]\), of the tumor volume.

Case where \(\gamma =-1\)

In this case, model (54) reduces to

The barrier S(t) can be explicitly derived as

for some constants A and B.

Theorem 7

The first time that a tumor with volume x(t) satisfying (56) first reaches the barrier S(t) follows the probability density function

The tumor’s mean age at this time is

where S(t) is as described in (57).

Proof

The proof is similar to the one given in Theorem 5. \(\square\)

Case where \(\gamma>-1\) with \(a=b\)

For \(\gamma>-1\), and in the case of no treatment/harvesting (that is, \(a=b\)) with \(x\in \left( 0,b^{1/(\gamma +1)}\right)\), the process

satisfies the Geometric Brownian stochastic differential equation

The moving barrier h(t) for which the first-passage-time probability for the first time the process u(t) reaches the barrier h(t) is obtained as

for some constants \(A>0\) and B. It can be shown that h(t) is a constant multiple of the expected value \(\mathbb {E}[u(t)|u_{0}]\). Let \(\tau _{u}=\inf \{t\ge 0\,\ u(t)=h(t)\}\) be the first passage time the process u(t) reaches the barrier h(t). Since \(u(t)>0\) almost surely, the process \(\tau _{u}\) is equivalent to the first passage time \(\tau _{X}^{S(t)}=\inf \left\{ t\ge 0\,\ x(t)=\left( \frac{b\,h(t)}{1+h(t)}\right) ^{\frac{1}{\gamma +1}}\right\}\) the process x(t) reaches the barrier

Theorem 8

The first time that a tumor with volume x(t) satisfying (54) (with \(a=b\)) first reaches the barrier S(t) in (62) follows the probability density function

The mean tumor age is

where \(u_{0}=\frac{ x_{0}^{(\gamma +1)}}{b-x_{0}^{(\gamma +1)}}\).

Proof

The result follows from showing that the distribution of \(\tau _{u}\) is the same as the distribution of \(\tau _{x}\). \(\square\)

Figures 11 and 12 confirm the result obtained in Theorem 8 using \(B=-(\gamma +1)\left( ar+\frac{b^{2}\sigma ^{2}}{2}(\gamma +1)\right)\) and \(B=-0.5(\gamma +1)\left( ar+\frac{b^{2}\sigma ^{2}}{2}(\gamma +1)\right)\), respectively, with parameters \(r=1\), \(\gamma =0.2\), \(b=e^{1}\), \(E=0\), \(\sigma =0.3\), \(x_{0}=1.5\), and \(A=3\). The case \(B=-(\gamma +1)\left( ar+\frac{b^{2}\sigma ^{2}}{2}(\gamma +1)\right)\) results in a constant barrier. For appropriate value of A, the constant barrier can help quantify the time dynamics of tumor progression or resistance emergence, offering critical insights for treatment strategies and prognosis. Depending on the values of A and B, the moving barrier S(t) in (62) represents a dynamically adjusted tumor burden limit based on patient-specific responses to treatment.

Case \(a\ne b\)

Theorem 9

If \(a\ne b\) and \(\gamma>-1\), the average age that a tumor with volume x(t) satisfying (53) first reaches the size \(S_{0}\) is obtained as

where \(u_{0}=u(x_{0})\), \(\epsilon ^{*}=u(S_{0})\),

Proof

For \(\gamma \ne -1\), \(a\ne b\), the process

satisfies the logistic stochastic differential equation

The first passage time \(\tau ^{\epsilon }_{X}\) the process x(t) reaches the barrier \(\epsilon\) is equivalent to the first passage time \(\tau ^{\epsilon ^{*}}_{u}=\inf \left\{ t\ge 0\,\ u(t)=\epsilon ^{*}\right\}\) the process v(t) reaches the barrier \(\epsilon ^{*}=\frac{ \epsilon ^{\gamma +1}}{b-\epsilon ^{\gamma +1}}\). The remainder of the result follows from Theorem 6. \(\square\)

The parameters used to generate Table 3 are \(r=1\), \(\gamma =0.2\), \(b=e^{\gamma +1}\), \(E=b/5\), \(\sigma =0.3\), \(x_{0}=1.5\), \(S_{0}=1.8\). The table shows that the estimated MFPT derived by taking the mean of the first time {\(\tau _{X}^{l}\}_{l=1}^{L}\) the process \(\{x^{l}(t_{j})\}_{j=1}^{N}\) (derived as a Milstein discretized solution of (54)) reaches the boundary \(S_{0}\) is converging to the exact average derived in (65) for large sample size N and large number of simulations L.

Results

Application to lung tumor growth

The work done here is applied to two different data. First, we apply the data to calculate the first passage time that tumor volume from the number of Murine Lewis lung Carcinoma (LLC) cells24,25 in a C57BL/6 mouse first reaches a certain barrier. The data used in this study are published data from the work of Benzekry et al.24,25. The lung tumor cells were collected by subcutaneously implanting anesthetized 6 to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice on the caudal half of the back. Tumor size was measured regularly over time, spanning 4 to 22 days. The data consist of identifier IDs for each of 20 control mice, the time of day the tumor measurement was taken after implantation, and the volume of the lung tumor in the range of 14-1492 \(mm^3\). Also, we apply the work done here to tumor volume experiments on 8 control mice in the work of Daskalakis26. Here, the flank of \(n=37\) nude mice was implanted with the cells from a human glioma cell line and a subcutaneous tumor (xenograft) was allowed to grow. For comparison purposes, we refer to models (3), (16), (39), and (53) as models 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Since these data are control experimental data without treatment, we set \(E=0\)and use models 1, 3, and 4 for the data analysis. The parameters in the models are estimated by fitting the models to these experimental lung tumor data using Conditional Least Squares Estimation scheme27. These estimates are then used to calculate the average age that the volume of the lung tumor first double in size.

These ages (in days) are recorded in Table 4. It is calculated for each of the specimen in the experimental data24,25,26 by subtracting the initial time \(t_{0}\) from the average first passage time the volume reaches the size \(2x_{0}\).

The exact and estimated tumor sizes for the 20 experimental control data in Benzekry et al.24,25 are given in Fig. 13. Likewise, exact and estimated tumor sizes for the 9 experimental control data in the work of Daskalakis26 are given in Fig. 14. The Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) for each estimation is given in Appendix Table B.5.

Estimation of the volume of lung tumor in Daskalakis26 using models 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Discussion

The evaluation of the efficacy of anti-cancer therapies is a critical component in understanding cancer treatment outcomes, particularly in assessing the time it takes for a tumor to enter remission. One of the most informative ways to measure treatment efficacy is by evaluating the time at which the tumor first reaches certain oncological time metrics, typically measured by a significant change in tumor volume. This time is statistically captured using the concept of the First Passage Time (FPT) and its associated First Passage Time Distribution (FPTD).

In the context of tumor growth and therapy response, the threshold or barrier is often not static but rather dynamic, evolving with time as a result of ongoing treatment or tumor response mechanisms. This evolving threshold is referred to as a moving barrier, which may shrink or expand depending on the treatment’s impact or the tumor’s natural progression. The formulation of a closed-form solution for the FPTD depends on the structure of the moving barrier and the underlying stochastic model governing tumor growth. In particular, obtaining a closed-form expression for the FPTD requires a deep understanding of the probabilistic behavior of the tumor volume and the interaction between the tumor’s stochastic dynamics and the shifting barrier. The complexity of this problem arises because the tumor’s progression is influenced by multiple random factors, such as genetic mutations, microenvironmental fluctuations, immune response variability, and drug interactions, making deterministic models insufficient for accurate prediction.

In this study, we construct and analyze stochastic models that describe the tumor volume at any given time with or without therapeutic intervention. These models incorporate random fluctuations in tumor growth (often modeled using stochastic differential equations), which capture the inherent uncertainties in tumor progression and treatment response. By examining these stochastic models, we derive a corresponding moving barrier for tumor volume, which represents the evolving size threshold. A major contribution of this work lies in obtaining a closed-form expression for the FPTD for the first time the tumor size reaches the moving barrier. This closed-form solution is crucial as it allows for the direct computation of the probability that remission occurs within a specific time frame, given the initial tumor size and the characteristics of the treatment. The derived FPTD also provides insight into the distribution of time intervals in which oncological occurences can be expected, allowing for probabilistic predictions about treatment success.

To validate the derived FPTD models and their predictions, we apply them to experimental data from Murine Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) models reported in the work of Benzekry et al.24,25and tumor volume experiments conducted by Daskalakis26. The LLC data provide a suitable test case as it represents fast-growing tumors with no therapeutic intervention, allowing us to evaluate the predictive power of the FPTD model.

Data availability

The data used in this study are published data and can be found in the work of Benzekry et al.24,25 (http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003800 and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3572401) and Daskalakis26 (https://www.causeweb.org/tshs/tumor-growth/).

References

Albano, G., Barrera, A., Giorno, V., Román, R. & Ruiz, F. T. A note on the evaluation of first-passage-time probability densities. J. Appl. Probab. 20, 197–201 (1983).

Gatenby, R. A. & Gillies, R. J. A microenvironmental model of carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8(1), 56–61 (2008).

Gatenby, R. A. & Brown, J. S. Integrating evolutionary dynamics into cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 675–686 (2020).

Ruchalski, K., Dewan, R., Sai, V., McIntosh, L. J. & Braschi-Amirfarzan, M. Imaging response assessment for oncology: An algorithmic approach. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 9, 100426 (2022).

Román-Román, P., Román-Román, S., José Serrano-Perez, J. & Torres-Ruizz, F. Using first-passage times to analyze tumor growth delay. Mathematics9 (6), 642. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9060642 (2021).

Buonocore, A., Nobile, A. G. & Ricciardi, L. A new integral equation for the of first-passage-time probability densities. Adv. Appl. Probab. (1987).

Hufton, P. G., Buckingham-Jeffery, E. & Galla1, T. First-passage times and normal tissue complication probabilities in the limit of large populations. Sci. Rep.10, 8786. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64618-9 (2020).

Weiss, W. Tumor doubling time. Chest 79(5), 612–613 (1981).

Ricciardi, L. M., Sacerdote, L. & Sato, S. On an integral equation for first-passage-time ability densities. J. Appl. Probab. 21, 302–314 (1984).

Albano, G., Barrera, A., Giorno, V., Román-Román, P. & Torres-Ruiz, F. First passage and first exit times for diffusion processes related to a general growth curve. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 126, 107494 (2023).

Jáimez, R. G., Román, P. R. & Ruiz, F. T. A note on the Volterra integral equation for the first-passage-time probability density. J. Appl. Probab. 32, 635–648 (1995).

Tuckwell, H. C. & Wan, F. Y. M. First-passage time of Markov processes to moving barriers. J. Appl. Probab. 21, 695709 (1984).

Otunuga, O. M. Tumor growth and population modeling in a toxicant-stressed random environment. J. Math. Biol. 88, 18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00285-023-02035-y (2024).

Albano, G., Giorno, V., Román-Román, P. & Torres-Ruiz, F. Inferring the effect of therapy on tumors showing stochastic Gompertzian growth. J. Theor. Biol. 276, 67–77 (2011).

Albano, G., Giorno, V., Román-Román, P., Román-Román, S. & Torres-Ruiz, F. Estimating and determining the effect of a therapy on tumor dynamics by means of a modified Gompertz diffusion process. J. Theor. Biol. 364, 206–219 (2015).

Mould, D. R. & Upton, R. N. Basic concepts in population modeling, simulation, and model-based drug development-part 2: Introduction to pharmacokinetic modeling methods. CPT Pharmacom. Syst. Pharmacol.17 (4), e38. https://doi.org/10.1038/psp.2013.14 (2013).

Park, K. A review of modeling approaches to predict drug response in clinical oncology. Yonsei Med. J.58(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2017.58.1.1 (2017).

Swanson, E. R., Kose, E., Zollinger, E. A. & Elliott, S. L. Mathematical modeling of tumor and cancer stem cells treated with CAR-T therapy and inhibition of TGF-\(\beta\). Bull. Math. Biol.84, 58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11538-022-01015-5 (2022).

Elliott, S. L., Kose, E., Lewis, A. L., Steinfeld, A. E. & Zollinger, E. A. Modeling the stem cell hypothesis: Investigating the effects of cancer stem cells and TGF-\(\beta\) on tumor growth. MBE 16(6), 7177–7194 (2019).

Olver, F. W., Lozier, D. W., Boisvert, R. F. & Clark, C. W. NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions (National Institute of Sciences and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce and Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Whittaker, E. T. & Watson, G. N. A Course in Modern Analysis 4th edn. (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Bateman, H. Higher Transcendental Functions. Vol. 1, 2 (McGraw-Hill, 1953).

Giet, J.-S., Vallois, P. & Wantz-Mézières, S. The logistic S.D.E. Theory Stoch. Process.20(1), 28–62 (2015).

Benzekry, S., Lamont, C., Weremowicz, J., Beheshti, A., Hlatky, L. & Hahnfeldt, P. Tumor growth kinetics of subcutaneously implanted Lewis lung carcinoma cells [Data set]. PLoS Comput. Biol.10 (8), e1003800 (2019). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3572401

Benzekry, S., Lamont, C., Beheshti, A., Tracz, A., Ebos, J. M. L., Hlatky, L. & Hahnfeldt, P. Classical mathematical models for description and prediction of experimental tumor growth. PLoS Comput. Biol.10 (8), e1003800. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003800

Daskalakis, C. Tumor Growth Dataset. TSHS Resources Portal. https://www.causeweb.org/tshs/tumor-growth/ (2016).

Klimko, L. A. & Nelson, P. I. On conditional least squares estimation for stochastic processes. Ann. Stat. 6(3), 629–642 (1978).

Otunuga, O. M. Time-dependent probability density function for general stochastic logistic population model with harvesting effort. Physica A 573, 125931 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The author sincerely thanks the handling editor and referees for their insightful comments, which have significantly enhanced the presentation and content of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Olusegun Michael Otunuga performed the following: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Analysis, Writing, Visualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Otunuga, O.M. Stochastic modeling and first-passage-time analysis of oncological time metrics with dynamic tumor barriers. Sci Rep 15, 14941 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95475-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95475-z

- Springer Nature Limited