Abstract

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are the second leading causes of maternal mortality and morbidity. It also results in high perinatal mortality and morbidity. Since eclampsia is preceded by preeclampsia and shows the progression of the disease, they share the same pathogenesis and determining factors. The purpose of this study was to determine determinants of preeclampsia, since it is essential for its prevention and/or its associated consequences. An unmatched case–control study was conducted from September 1–30, 2023 among women who gave birth from June 1, 2020, to August 31, 2023, at Hiwot Fana Comprehensive Specialized University Hospital. Women who had preeclampsia were considered cases, while those without were controls. The sample size was calculated using EPI Info version 7 for a case–control study using the following assumptions: 95% confidence interval, power of 80%, case-to-control ratio of 1:2, and 5% non-response rate were 305. Data was collected using Google Form, and analyzed using SPSS version 26. Variables that had a p-value of < 0.05 on multivariable logistic regression were considered statistically significant, and their association was explained using an odds ratio at a 95% confidence interval. A total of 300 women (100 cases and 200 controls) with a mean age of 24.4 years were included in the study. Rural residence (AOR 2.04, 95% CI 1.10–3.76), age less than 20 years (AOR 3.04, 95% CI 1.58–5.85), history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (AOR 5.52, 95% CI 1.76–17.33), and no antenatal care (AOR 2.38, 95% CI 1.19–4.75) were found to be the determinants of preeclampsia. We found that living in a rural areas, previous history of preeclampsia, no antenatal care, and < 20 years of age were significantly associated with preeclampsia. In addition to previous preeclampsia, younger and rural resident pregnant women should be given attention in preeclampsia screening and prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) consist of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, and superimposed preeclampsia on chronic hypertension1. Preeclampsia is a multisystem syndrome that develops during the second half of pregnancy and is characterized by a new onset of hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation, or in the absence of proteinuria, the finding of maternal organ dysfunction, which will disappear postnatally. Throughout the world, 2–7% of pregnant mothers develop preeclampsia and its complications2,3,4,5,6. Eclampsia refers to the occurrence of new-onset, generalized, tonic–clonic seizures or coma in a patient with preeclampsia after ruling out of other causes. It is the convulsive manifestation of preeclampsia and one of several clinical manifestations at the severe end of the preeclampsia spectrum. Since eclampsia is a spectrum of preeclampsia, they have similar pathogenesis and determinant factors7. Though the exact pathogenesis of preeclampsia is not yet explained well, there are different proposed theories. Among these, the first is abnormal placental development, in which early placental development characterized by the defective extravillous trophoblast invasion and defective spiral artery remodeling. This will result in decreased blood supply to the placenta, ischemia at the retro placental area, and the release of antiangiogenic factors like soluble fms like tyrosine kinase- 1(sFlt-1) and soluble endoglin. These soluble factors will lead to systemic vasospasm and hypertension. Other theories include systemic endothelial dysfunction, infection or inflammation, genetics, and an increased response to angiotensin II8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

Preeclampsia has been classified based on the gestational age by international Society for the study of hypertension in pregnancy (ISSHP) as early onset, preterm, late-onset and term preeclampsia15,16. American College of Obstetrician and gynecology classifies symptomatically as preeclampsia with and without severity features17. The severity features of the preeclampsia include: severe headache, blurring of vision, HELLP(Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes, and Low platelet count) syndrome, pulmonary edema, organ derangement, and the last spectrum is occurrence convulsion which will change the name to eclampsia18.

Preeclampsia/eclampsia is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality and morbidity contributing 16–39% of all maternal deaths19,20,21,22,23.

Beyond its burden on maternal health, preeclampsia is also associated with reduced blood supply to the placenta with consequent impairment in fetal growth, oxygenation, and increased risk of stillbirth. Additionally, a high proportion of women with PE require premature delivery for maternal and/or fetal indications and therefore the neonates are subjected to the additional risks arising from prematurity24,25,26. Despite its high impact on maternal and perinatal health, especially in low resource settings like Ethiopia, research on determinants of preeclampsia is limited. This study was conducted to identify determinants of preeclampsia among women who gave birth in a university hospital in eastern Ethiopia.

Methods

Study area and period

The study was conducted at Hiwot Fana Comprehensive University Hospital (HFCUH), Harari Regional State, which is 511 km to the east of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The hospital is an affiliate of Haramaya University, and it is the oldest and major referral center for the eastern part of the country, including the Harari region, East Hararghe zone, Somali region, and Dire Dawa administrative city. Annually, the number of deliveries in this hospital is more than 4500. This study was conducted from September 1 to 30, 2023.

Study design

Institutional-based unmatched case–control study was conducted.

Study population

All women who gave birth in HFCUH from June 1, 2020, to August 31, 2023, diagnosed with preeclampsia, including eclampsia constituted cases whereas those with no hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were controls.

Definition of cases

Any women diagnosed with preeclampsia or eclampsia by the attending clinician regardless of the severity features or organ derangement were considered as a case.

Selection of controls

For each case, two controls (one who gave birth before and one after the case on the same day without any hypertensive disorders of pregnancy) were selected.

Exclusion criteria

Women with incomplete medical records (if more than 25% of major independent variables are absent), or not clearly identified whether the woman has hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or not, was excluded for study.

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated using EPI Info version 7 for a case–control study using the following assumptions: 95% confidence interval, power of 80%, case-to-control ratio of 1:2, and considering percentage of exposure from the previous study done in Bahir Dar (family history)27, the calculated sample size was 290 (97 cases and 193 controls) considering 5% non-response rate, the final sample size became 305 (102 cases, and 203 controls).

Sampling procedure

After identifying medical registration number (MRN) of all women with preeclampsia in the department during the study period was obtained from the delivery logbooks, operation register, admission and discharge registers, and the gynecology ward register, a sampling frame was prepared using their MRN. Then, a simple random sampling was applied to select cases using computer generated random table (https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randomN1/). For each case, two controls, one preceding and one proceeding controls who gave birth on the same date was identified and included into the study.

Data collection procedure

Data was collected (filled) on google form, from medical records using a pretested checklist by trained OBGYN residents. Data on sociodemographic, obstetrics, and medical characteristics as well as maternal and fetal outcome was collected by review of medical records. The checklist was adapted from similar studies and pre-tested on 5% of medical records from nearby hospital.

Operational definition

Preeclampsia is considered as a case in this study based on the records of Preeclampsia or eclampsia on patients MRN by the attending clinician.

Data quality control

To assure data quality, training was given for data collectors, how to collect, get the right information, and the entire content and scope of the checklist. The checklist was adapted from similar studies and pre-tested in 5% of the medical records from nearby hospital. Data collection was supervised and all completed checklists were checked by authors for accuracy, consistency, and completeness at the conclusion of each data collection day.

Data processing and analysis

All the responses from the google form were downloaded on excel sheet, which was cleaned and exported to SPSS version 26 for analysis. Mean and standard deviation were computed as descriptive statistics and presented using tables. Each potential factor related to the case and the control group was first be subjected to a bivariate analysis. Then, multivariable logistic regression was applied to variables with a p < 0.25 after checking for multicollinearity. A backward likelihood ratio with a 0.1 probability of removal was used to develop the model. The adjusted odds ratio was estimated with 95% confidence interval (CI) to show the strength of association, and a p value of < 0.05 was used to declare statistical significance association. The goodness of fit of the final model was checked using the Hosmer Lemeshow test.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC) of Haramaya University College of Health and Medical sciences prior to data collection with reference number IHRERC/156/2023. Informed, voluntary, written and signed consent was obtained from the HFSUH administration and heads of the gynecology and obstetrics wards. Information gained from medical record charts and the individuals will be held anonymous and confidential.

Results

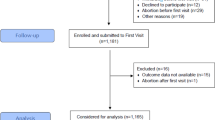

Of the 305 records identified, 300 (98.4%) medical records were reviewed: 100 cases and 200 controls. The mean age of participants was 24.4 years (ranging from 16 to 48 years). Majority of the cases were less than 20 years (48%) old while 70 percent of the controls were between 20 and 34 years and more than half (57.3%) were rural residents (Table 1). From the cases, 64% were preeclampsia, while 36% were eclampsia.

Details of feto-maternal outcomes at birth and at discharge are indicated in Table 2. Majority of the cases and controls had alive neonate at birth and discharge. Compared to cases, controls had high low birthweight, intrauterine fetal death, and fetal complications (Table 2).

Determinants of preeclampsia

In the bivariate analysis, as age, residence, history of HDP, gravidity, anemia in current pregnancy, ANC follow-up, and sex of the fetus were significantly associated with preeclampsia at p value < 0.25. However, only residence, history of preeclampsia, age, and antenatal care were remained significantly associated with preeclampsia at p < 0.05 in the multiple logistic regression.

Accordingly, the odd of preeclampsia among women younger than 20 years were 3.04 times higher compared to those who are 20–35 years old (AOR 3.04, 95% CI 1.58–5.85), those who are living in rural areas were 2.04 times more likely to develop preeclampsia/eclampsia when compared to those who were from urban residents (AOR 2.04, 95% CI 1.10–3.76). Similarly, women who had a history of preeclampsia/eclampsia in the previous pregnancy were 5.52 times more likely to develop preeclampsia/eclampsia when compared to those who had no history of preeclampsia/eclampsia in the previous pregnancy (AOR 5.52, 95% CI 1.76–17.33). Moreover, those study participants who had no ANC follow-up were 2.38 times more likely to develop preeclampsia/eclampsia when compared to their counterparts (AOR 2.38, 95% CI 1.19–4.75) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study was conducted at Hiwot Fana Comprehensive University Hospital, eastern Ethiopia to identify determinants of preeclampsia. According to this study, maternal age of < 20 years, rural residence, history of preeclampsia, and no ANC follow-up were found to be independently associated with preeclampsia.

Consistent with previous findings, preeclampsia was found to be more likely among young women (< 20 years) compared with those 20–34 years of age. A similar findings were reported in Washington28, Bahir Dar29, Colombia30, and Gedeo zone31. Different studies found that younger age is associated with de novo preeclampsia, while those older than 35 years are associated with superimposed preeclampsia in chronic hypertension32,33. Young women are exposed to trophoblast for the first time, which will be associated with abnormal placental development (failure of trophoblast invasion or failure of spiral artery remodeling) which leads to the release of antiangiogenic factors like soluble fms like tyrosine kinase-1, which further leads to systemic vasospasm and hypertension12,34.

We also found that rural residents were more likely to develop preeclampsia compared to those in urban residents. Similar findings have been reported in other hospitals in Ethiopia: Nekemt hospital35, Tigray Region36, and Chiro Hospital37. This might be explained by lack of ANC follow-up, poor health-seeking behavior, and not receiving timely preventive interventions, like aspirin, compared to urban areas14. As expected, we found that women with preeclampsia were more likely to have history of preeclampsia. Consistent findings were reported in studies conducted in Addis Ababa38, Hosanna39, Tigray40, sub-Saharan Africa41,42, the University of Tennessee (Memphis)43,44, Colombia30, and the Netherlands45. Despite the common notion that preeclampsia disappears postnatally, this reminds us of the importance of continued support for such women, including counseling about the future risk of recurrence and screening cardiovascular diseases postnatally and preconception for the next pregnancy46.

Similarly, women with preeclampsia were more likely to have no ANC compared to their counterparts. This study is consistent with previously reported studies in Bahirdar27, a systematic review in sub-Saharan Africa42. While ANC will not stop its causation or predict those at risk, it gives the opportunity to give protective prophylaxis (like aspirin) or identify maternal risk factors for timely management or counseling. This indicates that having ANC follow-up will decrease the risk since they receive counseling about nutrition, and those who are at risk of developing it will receive preventive interventions like aspirin.

Generally, similar to this study rural residence and not having ANC follow-up were significantly associated with the studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries, which directly imply the poor and non-equitable health care practice. This indicates that stakeholders in LMIC are expected to work in ensuring health equity. While having history of preeclampsia and younger age is similar with both high- and low-income countries. History of preeclampsia may be related with the same underlying predisposition condition like genetic factors while being young is associated with abnormal placental development and immunological response to the first exposure to trophoblast. For this reason, being younger than 20 years and previous history of preeclampsia is an alarming sign for screening and starting prevention.

Limitations

The limitation of this study is that, since it is a retrospective medical chart review, important variables were missing from the medical registration.

Conclusion

This study found that living in a rural residence, having a previous history of preeclampsia or eclampsia, not having ANC, and being less than 20 years old are significantly associated with preeclampsia and eclampsia. For this reason, in addition to the previous history of preeclampsia, attention should be given to screening and taking preventive action against preeclampsia in younger and more rural pregnant women.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed for this objective is included in this article, and non-person-identifying data can also be accessed from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- HDP:

-

Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy

- HFCSUH:

-

Hiwot Fana Comprehensive Specialized University Hospital

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- IHRERC:

-

Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee

- MRN:

-

Medical registration number

- OBGYN:

-

Obstetrics and Gynecology

- PE:

-

Preeclampsia

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

References

Sutton, A. L. M., Harper, L. M. & Tita, A. T. N. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 45, 333–347 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. Preeclampsia prevalence, risk factors, and pregnancy outcomes in Sweden and China. JAMA Netw. Open 4, 1–14 (2021).

Robillard, P. Y., Dekker, G., Scioscia, M. & Saito, S. Progress in the understanding of the pathophysiology of immunologic maladaptation related to early-onset preeclampsia and metabolic syndrome related to late-onset preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226, S867–S875 (2022).

Yagel, S., Cohen, S. M. & Goldman-Wohl, D. An integrated model of preeclampsia: A multifaceted syndrome of the maternal cardiovascular-placental-fetal array. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226, S963–S972 (2022).

Tanner, M. S., Davey, M. A., Mol, B. W. & Rolnik, D. L. The evolution of the diagnostic criteria of preeclampsia-eclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226, S835–S843 (2022).

Erez, O. et al. Preeclampsia and eclampsia: The conceptual evolution of a syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226, S786–S803 (2022).

Sibai, B. M. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. 105, 402–410 (2005).

Makris, A. et al. Uteroplacental ischemia results in proteinuric hypertension and elevated sFLT-1. Kidney Int. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ki.5002175 (2007).

Redman, C. W. G. & Sargent, I. L. Systemic inflammatory. Response. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.07.005 (2004).

Wang, X., Athayde, N. & Trudinger, B. A proinflammatory cytokine response is present in the fetal placental vasculature in placental insufficiency. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. https://doi.org/10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00652-5 (2003).

Yinon, Y. et al. Severe intrauterine growth restriction pregnancies have increased placental endoglin levels. Placenta 172, 77–85 (2008).

Article, R. Vascular biology of preeclampsia. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03259.x (2009).

Maynard, S., Epstein, F. H. & Karumanchi, S. A. Preeclampsia and angiogenic imbalance. Annu. Rev. Med. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.59.110106.214058 (2008).

Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) & ICF. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Final Report. (2021).

Magee, L. A. et al. The 2021 International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 27, 148–169 (2022).

Poon, L. C. et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) initiative on pre-eclampsia: A pragmatic guide for first-trimester screening and prevention. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 145, 1–33 (2019).

Espinoza, J., Vidaef, A., Pettker, C. M. & Simhan, H. M. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician – gynecologists. Obstet. Gynecol. 133, 168–186 (2020).

Press, D. Severe preeclampsia and eclampsia : Incidence , complications , and perinatal outcomes at a low-resource setting , Mpilo Central Hospital ,. 353–357 (2017).

Troiano, N. H. & Witcher, P. M. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: Classification, causes, preventability, and critical care obstetric implications. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 32, 222–231 (2018).

Musarandega, R., Nyakura, M., Machekano, R., Pattinson, R. & Munjanja, S. P. Causes of maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of studies published from 2015 to 2020. J. Glob. Health 11, 04048 (2021).

Joseph, K. S. et al. Maternal mortality in the United States: Recent trends, current status, and future considerations. Obstet. Gynecol. 137, 763–771 (2021).

Thoma, M. E. & Declercq, E. R. All-cause maternal mortality in the US before vs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 5, E2219133 (2022).

Bwana, V. M., Id, S. F. R., Mremi, I. R., Lyimo, E. P. & Mboera, L. E. G. Patterns and causes of hospital maternal mortality in. PLoS One 24, 1–22 (2019).

Melese, M. F., Badi, M. B. & Aynalem, G. L. Perinatal outcomes of severe preeclampsia/eclampsia and associated factors among mothers admitted in Amhara Region referral hospitals, North West Ethiopia, 2018. BMC Res. Notes 12, 1–6 (2019).

Meazaw, M. W., Chojenta, C., Taddele, T. & Loxton, D. Audit of clinical care for women with preeclampsia or eclampsia and perinatal outcome in Ethiopia: Second National EmONC Survey. Int. J. Womens. Health 14, 297–310 (2022).

Irene, K. et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in women with eclampsia by mode of delivery at Riley mother baby hospital: A longitudinal case-series study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 1–14 (2021).

Tesfa, E., Munshea, A., Nibret, E. & Gizaw, S. T. Determinants of pre-eclampsia among pregnant women attending antenatal care and delivery services at Bahir Dar public hospitals, northwest Ethiopia: A case-control study. Heal. Sci. Reports 6, 1–11 (2023).

Lisonkova, S. & Joseph, K. S. Incidence of preeclampsia: Risk factors and outcomes associated with early- versus late-onset disease. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.019 (2013).

Endeshaw, M. et al. Obesity in young age is a risk factor for preeclampsia : A facility based case-control study, northwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1029-2 (2016).

Ayala-ramírez, P. et al. Heliyon Risk factors and fetal outcomes for preeclampsia in a Colombian cohort. Heliyon 6, e05079 (2020).

Mareg, M., Molla, A., Dires, S., Mamo, Z. B. & Hagos, B. Determinants of preeclampsia among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care (ANC) and delivery service in Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia: Case control-study. Int. J. Womens. Health 12, 567–575 (2020).

Jasovic, V. & Stoilova, S. Previous pregnancy history, parity, maternal age and risk of pregnancy induced hypertension. Bratisl Lek Listy 112, 188–191 (2011).

Sheen, J. et al. Maternal age and risk for adverse outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 219(390), e1-390.e15 (2018).

Maynard, S. E. & Karumanchi, S. A. Angiogenic Factors. Preeclampsia. 31, 33–46 (2011).

Hinkosa, L. BMC Pregnancy and childbirth risk factors associated with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy in Nekemte referral Hospital, from July 2015 to June 2017, Ethiopia: Case control study" hypertensive disorders in pregnancy in Nekemte referral Hospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 9, 1–9 (2017).

Kahsay, H. B., Gashe, F. E. & Ayele, W. M. Risk factors for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy among mothers in Tigray region, Ethiopia: Matched case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 1–10 (2018).

Katore, F. H., Gurara, A. M. & Beyen, T. K. Determinants of preeclampsia among pregnant women in chiro referral hospital, oromia regional state, Ethiopia: Unmatched case– control study. Integr. Blood Press. Control 14, 163–172 (2021).

Grum, T., Seifu, A., Abay, M., Angesom, T. & Tsegay, L. Determinants of pre-eclampsia/Eclampsia among women attending delivery Services in Selected Public Hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A case control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 1–7 (2017).

Babore, G. O., Aregago, T. G., Ermolo, T. L., Nunemo, M. H. & Habebo, T. T. Determinants of pregnancy-induced hypertension on maternal and foetal outcomes in Hossana town administration, Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia: Unmatched case-control study. PLoS One 16, 1–16 (2021).

Haile, T. G. et al. Determinants of preeclampsia among women attending delivery services in public hospitals of central Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A case-control study. J. Pregnancy 2021, 4654828 (2021).

Tesfa, E. et al. Prevalence and determinants of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 15, 1–21 (2020).

Meazaw, M. W., Chojenta, C., Muluneh, M. D. & Loxton, D. Systematic and meta-analysis of factors associated with preeclampsia and eclampsia in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One 15, 1–23 (2020).

Sibai, B. M., El-Nazer, A. & Gonzalez-Ruiz, A. Severe preeclampsia-eclampsia in young primigravid women: Subsequent pregnancy outcome and remote prognosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 155, 1011–1016 (1986).

van Rijn, B. B., Hoeks, L. B., Bots, M. L., Franx, A. & Bruinse, H. W. Outcomes of subsequent pregnancy after first pregnancy with early-onset preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 195, 723–728 (2006).

Gaugler-Senden, I. P. M., Berends, A. L., de Groot, C. J. M. & Steegers, E. A. P. Severe, very early onset preeclampsia: Subsequent pregnancies and future parental cardiovascular health. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 140, 171–177 (2008).

Turbeville, H. R. & Sasser, J. M. Preeclampsia beyond pregnancy. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 11, 315 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Haramaya University for funding this research.

Funding

This research was funded by Haramaya University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.G.E., S.B., and A.K.T.: Contributed in conceptualization and writing of proposal, methodology; ethical acquisition, supervision; data curation; formal analysis; writing the original draft; and review and editing. D.F., and A.D.: Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing the original draft and final draft, and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eticha, T.G., Berhe, S., Deressa, A. et al. Determinants of preeclampsia among women who gave birth at Hiwot Fana Comprehensive Specialized University Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia: a case–control study. Sci Rep 14, 18744 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69622-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69622-x

- Springer Nature Limited