Abstract

Psoriasis is a chronic skin disease that negatively impacts on patient’s life. A holistic approach integrating well-being assessment could improve disease management. Since a consensus definition of well-being in psoriasis is not available, we aim to achieve a multidisciplinary consensus on well-being definition and its components. A literature review and consultation with psoriasis patients facilitated the design of a two-round Delphi questionnaire targeting healthcare professionals and psoriasis patients. A total of 261 panellists (65.1% patients with psoriasis, 34.9% healthcare professionals) agreed on the dimensions and components that should integrate the concept of well-being: emotional dimension (78.9%) [stress (83.9%), mood disturbance (85.1%), body image (83.9%), stigma/shame (75.1%), self-esteem (77.4%) and coping/resilience (81.2%)], physical dimension (82.0%) [sleep quality (81.6%), pain/discomfort (80.8%), itching (83.5%), extracutaneous manifestations (82.8%), lesions in visible areas (84.3%), lesions in functional areas (85.8%), and sex life (78.2%)], social dimension (79.5%) [social relationships (80.8%), leisure/recreational activities (80.3%), support from family/friends (76.6%) and work/academic life (76.5%)], and satisfaction with disease management (78.5%) [treatment (78.2%), information received (75.6%) and medical care provided by the dermatologist (80.1%)]. This well-being definition reflects patients’ needs and concerns. Therefore, addressing them in psoriasis will optimise management, contributing to better outcomes and restoring normalcy to the patient’s life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic skin disease that negatively impacts on patients’ quality of life (QoL)1. In addition, some psoriasis-associated symptoms may trigger stress2,3, low self-esteem4 and stigmatisation5, impairing the patient’s emotional well-being6 and affecting their social7 and family relationships8 and working capacity9,10. Therefore, the disease burden goes beyond the visible nature of the associated psoriatic lesions1.

In recent times, therapies have improved significantly in terms of efficacy, safety and tolerability, leading to a reduction in the severity and extent of the disease11. However, enhancements in the signs and symptoms of the disease may not have the same impact on the patients’ overall perception of their pathology, their beliefs or coping skills12. Hence, it is crucial to develop therapeutic interventions aimed at improving patients’ well-being from a holistic perspective, helping them return to the state of well-being they enjoyed prior to the disease.

Well-being is closely linked to QoL; however, both should be treated as separate concepts. Quality of life refers to the patient’s cognitive assessment of their health’s impact on their daily life13. Well-being is a more global and holistic concept that refers to the patient’s emotional response to their illness, treatment, and future13. Although related, the two concepts have important differences in approach and assessment. Therefore, the impact of the disease extends beyond its symptoms and signs14 and may result in stigmatisation and limitations in social and occupational functioning15. The concept of well-being encompasses all areas of life that may be affected by the disease16, including aspects that are not usually included in QoL17, which tends to focus on three dimensions, physical, mental, social and general health perception18.

Integrating well-being in managing diseases, such as psoriasis, where the relationship between psychosocial factors on the occurrence, severity and progression of the disease is well established19, could greatly contribute to a better understanding and improved treatment of the disease20. In this respect, the Global report on psoriasis published by the World Health Organization (WHO) pointed out the need to assess and consider the full spectrum of the person’s needs, including the issues related to their psoriasis, but also other issues related to their health and well-being9. However, there is currently no agreed definition of well-being in the context of psoriasis, making well-being assessment a challenge for patient management.

The incorporation of ‘well-being’ in the WHO’s definition of health as a ‘state of well-being and not merely the absence of disease21 has led to a growing body of research on this topic. Consequently, several international institutions, including the WHO, have defined the concept of well-being22,23. However, the different definitions, variety of approaches and complexity of the concept have made it difficult to reach an international consensus on how to address and measure it22,23,24,25,26. Nevertheless, despite no agreed definition27 there is broad agreement that well-being encompasses: mental health, functional status, life satisfaction, personal development, positive social relationships, positive emotions, and the absence of negative emotions22,23.

As a starting point to developing a holistic approach to psoriasis, we must reach prior agreement on the definition of well-being in these patients. Therefore, here, we aim to achieve a multidisciplinary consensus, including patients’ perspectives, on defining the concept of well-being in psoriasis and establishing its dimensions and components.

Materials and methods

A scientific committee consisting of six dermatologists (ED, IB, FG, PC, PDLC, RRV), three hospital pharmacists (JLP, ER, EC), one psychologist (SR) and one patient association representative led the project. Members of the scientific committee were selected based on their experience in managing patients with psoriasis and their particular interest in patients’ well-being and QoL.

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Due to the nature of the study, which does not collect clinical data from participants, including data on drugs or interventions, and that the questions are related to participants’ perceptions, the approval of an Ethics Committee is not required, as defined in Royal Decree 957/2020 of 3 November28 and the Memorandum of Cooperation between Ethics Committees29. However, all participants had to read an information sheet and agree to take part in the study to participate.

The study comprised three phases: (1) literature review, (2) psoriasis patients’ consultation, and (3) Delphi consultation (Fig. 1).

Literature review

A literature review in PubMed database was carried out to identify existing definitions of well-being and establish the impact of psoriasis on patients’ well-being and QoL. The international PubMed database was consulted using MeSH terms and open terms combined with the Boolean operators “OR”, “AND”, or “NOT”. We used terms related to well-being [wellbeing, well-being, personal satisfaction (MeSH), life satisfaction, personal satisfaction], measurement instruments [health surveys (MeSH), questionnaire, self-assessment, scale, instrument, index, measure, tool], psoriasis [psoriasis (MeSH), psoriasis] and areas where it can have an impact (stress, emotional, anxiety, depression, suicide, suicidality, cognitive, impairment, body image, stigma, self-esteem, coping, psychosocial coping, sleep quality, sleep disorders, work productivity, pain, discomfort, itching, pruritus, symptoms, social, sexual, treatment satisfaction, life satisfaction, social and sexual health).

The search included publications in English or Spanish without a limited period (but the most recent articles were prioritised). Articles referring to patients with psoriatic arthritis exclusively or associated with a specific treatment were not reviewed. In addition, a search of the grey literature [Google Academic, WHO website (www.who.int), patient association websites (www.accionpsoriasis.org and www.psoriasis.org), dermatological societies’ websites (www.aedv.es and www.eadv.org)] was also performed using terms related to well-being and psoriasis.

Psoriasis patient consultation

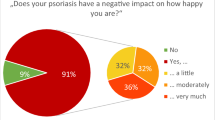

Through the patient association “Acción psoriasis” and with the active support of the patient community, an online patient survey addressed to 865 patients with psoriasis was conducted in November 2021 to identify the main unmet needs regarding the management of the emotional impact of psoriasis (details will be published elsewhere).

The survey included questions about the relationship between psoriasis and emotional health, the implications of psoriasis in patients’ lives, and the emotional management of psoriasis (information and care provided by healthcare professionals to address psychological needs).

Delphi consultation

The Delphi technique is a formal and systematic method for obtaining expert consensus on a particular knowledge area. Its main advantages include its high capacity to integrate information, identify positions of groups and individuals, and determine or order priorities30. It is an iterative process characterised by the anonymity of participants, controlled feedback of response and the statistical aggregation of group responses31,32.

The Delphi methodology does not have a set minimum number of panellists, as the decision is based on empirical and pragmatic factors. The qualities of the expert panel are more important than the number of panellists32. On average, Delphi consultations tend to have a sample size between 6 and 5033.

Two rounds of Delphi consultation were carried out using an electronic questionnaire. These rounds were considered sufficient to obtain consensus, prevent participant fatigue and reduce the number of non-responses34. The 1st-round questionnaire was available from 25 July to 16 September 2022, while the 2nd-round took place from 3 October to 9 November 2022.

Delphi questionnaire

The scientific committee developed the Delphi questionnaire based on the literature review results and the consultation with psoriasis patients.

The 1st-round Delphi questionnaire encompassed statements regarding the dimensions (n = 5) and components (n = 27) that integrate the definition of well-being (Table 1).

Panellists’ opinion on each dimension/component was assessed using a 7-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 2, mostly disagree; 3, somewhat disagree; 4, neither agree nor disagree; 5, somewhat agree; 6, mostly agree; 7, strongly agree).

Panellists also specified their level of agreement with the proposed definition of well-being (n = 1) and with the two options of descriptors suggested for each dimension (n = 5).

The questionnaire also included a free-text space where panellists could make observations and comments.

The 2nd-round questionnaire covered those dimensions/components for which consensus was not reached in the 1st-round. It was specifically tailored to each panellist, showing the panellist’s score and the position of the overall group (range of the greatest percentage of scores). In addition, it included two definitions of well-being (developed from the descriptors evaluated in the 1st-round) to be assessed by the panellists.

Delphi panellists

Delphi questionnaires were addressed to healthcare professionals, experts in psoriasis management and psoriasis patients who are members of the Spanish patient association (Acción Psoriasis). The Scientific Committee did not participate in the Delphi rounds. Healthcare professionals were selected and invited to participate through the study sponsor, while psoriasis patients were identified and invited to participate by the patient association.

Consensus definition

The consensus definition was established for each statement before data analyses, according to the common criteria35. Consensus was reached when at least 75% of the respondents agreed (strongly and mostly agree: 6, 7) or disagreed (strongly and mostly disagree: 1, 2) with dimension/component inclusion.

Data analysis

The descriptive analysis of panellists’ characteristics [mean and standard deviation (SD)] and the percentage of participants who selected each option (disagree: 1, 2; neutral: 3, 4, 5; agree: 6, 7) was conducted using STATA statistical software, V.14.

Ethics statement

Due to the nature of the study, an Ethics Committee approval is not required as clinical data, including medication or intervention data, is not collected and only participants’ perceptions are collected. However, all participants were required to read an information sheet and provide their consent to participate in the study.

Results

A total of 261 panellists participated in the Delphi consultation: 170 (65.1%) psoriasis patients [62.94% women, mean age 48.51 (SD 10.62) years, mean years from diagnosis 24.16 (SD 13.27)] and 91 (34.9%) healthcare professionals [56.04% women, mean age 48.42 (SD 10.08), mean years of experience 21.23 (SD 10.49), 66% dermatologists with experience in psoriasis or members of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) Psoriasis Group, 34% hospital pharmacists]. The response rate in the 2nd-round was 99% among health professionals and 85% among patients.

Dimensions of well-being

The panellists agreed that the concept of well-being was integrated by emotional, physical, social and satisfaction with disease management dimensions. However, the personal development dimension did not reach a consensus for its inclusion (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Components of the emotional dimension

The panellists agreed that the emotional dimension comprised stress (or distress), mood disorders, body image, stigmatisation/shame, self-esteem, and coping/resilience (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Components of the physical dimension

The panellists agreed that the physical dimension consisted of the following components: sleep quality, pain/discomfort, itching, extracutaneous manifestations, lesions in visible areas, lesions in functional areas, and sex life. However, no consensus was reached on physical fitness or cognitive impairment (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Components of the social dimension

The panellists reached consensus that the social dimension was formed by: social relations, leisure/recreational activities, support from family/friends, and work/academic life and integrated the social dimension. However, no consensus was reached on social rejection (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Components of the satisfaction with disease management dimension

The panellists agreed that satisfaction with treatment, satisfaction with the information received, and satisfaction with the medical care provided by the dermatologist were components of the satisfaction with disease management dimension. However, no consensus was reached on satisfaction with the care provided by other health professionals and satisfaction with public/private administration (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Components of the personal development dimension

No consensus was reached on including any of the proposed components of the personal development dimension (Table 3).

Definition and descriptors for each dimension

Panellists agreed on the following definition of well-being: “The concept of well-being in the psoriasis patient is multi-dimensional. It includes achieving emotional balance, having adequate overall health and control of the disease, enjoying positive social relationships, and being satisfied with disease care” (Table 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study aimed at defining well-being in psoriasis. Psoriasis is a chronic disease with a high physical and psychological impact on patients36,37; hence, establishing the definition of well-being in the context of psoriasis can help patients and healthcare professionals to better understand the disease, promoting a holistic approach to its management. The multidisciplinary nature of the consensus achieved, incorporating both healthcare professionals and patients with psoriasis, has enabled us to obtain an integrated and comprehensive definition of well-being.

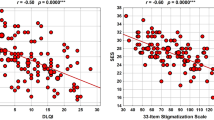

The emotional dimension and all its components reached consensus in the 1st-round, highlighting the high impact of psoriasis on this dimension. Previous studies have shown the emotional impact of psoriasis, which supports the inclusion of this dimension in the definition of well-being. Stress has been identified as one of the symptoms triggering the disease and is an exacerbating factor2,38; and research shows an association between psychological stress and the onset2, recurrence and severity of psoriasis3,38. In addition, other emotional disorders, such as anxiety or depression, are common in this population. For example, a previous study conducted in Spain using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire indicates that 40% and 38% of patients with psoriasis suffer from depression and anxiety, respectively39. Patients with therapy-controlled psoriasis are psychologically affected, and despite improvement in their skin lesions, a high percentage of patients still have symptoms of anxiety or depression36,40. Therefore, besides enhancing the patient’s skin lesions, psychological care is also necessary because the psychological impact may remain36. Mental health assessment is currently a crucial aspect of psoriasis patient care. Efforts are being made to optimise clinical practice by informing patients about this relationship, assessing the most appropriate treatment, and referring them to a specialist when necessary41,42.

The emotional dimension can be influenced by self-image and self-esteem, especially when psoriasis affects visible body areas. The visibility of psoriatic lesions may also cause fear, disquiet, rejection or embarrassment, contributing to the stigmatisation of patients5. Therefore, some studies suggest that patients with psoriasis are less satisfied with their body image than the general population43,44 and have lower self-esteem4. Thus, using effective coping strategies and training patients with lower health related quality of life to use these coping strategies is necessary to reduce the high impact of the illness on patients’ well-being45.

The physical dimension is also considered essential in the definition of well-being. Symptoms such as pain/discomfort, itching and scaling are common in patients with psoriasis and are considered the most bothersome46. In addition, these symptoms have a negative impact on the patient’s well-being, affecting their daily life, quality of sleep, mood, stigmatisation, and life satisfaction47,48. Sleep quality and sexual function are also affected by psoriasis. Previous studies show that patients with psoriasis have poorer sleep quality than the general population49 and have a higher prevalence of sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnoea and restless legs syndrome50. In addition, there is evidence that symptoms of insomnia in psoriasis are directly mediated by pruritus and pain50, so treatments that decrease the cutaneous symptoms in psoriasis successfully mitigate insomnia50. However, there was no consensus on the physical fitness component and cognitive impairment. Regarding physical fitness, psoriasis patients may have reduced willingness to engage in physical fitness due to lesions in functional areas and itching which can impact their motivation and overall physical fitness51. Although many respondents considered this component to be important, there was no consensus. It is worth nothing that the main causes of discomfort during physical activity, such as lesion location and pruritus, have achieved consensus. Some panellist may have interpreted physical fitness as a secondary consequence of these components.

Regarding cognitive impairment, several studies suggest a potential relationship between psoriasis and cognitive impairment, although the results are heterogeneus52,53. Hoiwever, this association seems to be stronger in patients with severe psoriasis. Althougt this component was considered relevant by many penellist, it did not reach consensus and was therefore left out of the definition.

Regarding sexual function, due to severity, pain or embarrassment in the case of genital implication54, both men and women with psoriasis are at increased risk of sexual dysfunction55. There was no consensus on the inclusion of the dimension or components of personal development in the concept of well-being, so it was left out of the definition. It is important to note that patients with psoriasis have achieved personal development thanks to improvements in current treatments and therapies. This means that the disease does not currently impede the personal and professional development of the patients.

Consensus was also reached on the inclusion of the social dimension in the definition of well-being. Panellists agreed that family support/friendships, social relationships, leisure/recreational activities, and work/activity were components of the social dimension. Previous studies indicate that psoriasis negatively impacts social interaction skills, making it challenging to make new friends, avoiding social engagements or modifying how one dresses56. In addition, it also affects work productivity, which is directly correlated with the severity of the disease10.

Fortunately, today’s ease of access to information about the disease by the general population has contributed to reducing the belief that it is a contagious disease, along with discrimination and trivialisation of the illness. This could have reduced the social rejection felt by patients, which may explain why the social rejection component did not reach a consensus among the panellists.

The dimension of satisfaction with disease management also reached consensus, as did the component’s satisfaction with treatment, with the care provided by the dermatologist and the information received. A recent study indicates that psoriasis patients’ dissatisfaction with the treatment received is very high (more than 50%)57; moreover, 40% of patients desire more effective therapies58. In contrast, consensus was not reached on satisfaction with the public/private administration and the care provided by other health professionals. In Spain, there is less interaction with other professionals, such as nurses or psychologists, with the dermatologist being the primary healthcare provider for these patients.

The description of well-being in patient with psoriasis, as agreed upon in this study, will enable healthcare professionals to assess the impact of each dimension in the patient with psoriasis, and determine what is the most important to them. Defining well-being can help healthcare professionals to understand well-being and achieve a patient-centred care.

In line with our results, a recent nationwide survey conducted in Italy aimed to identify key factors contributing to barriers impacting patients’ well-being, which indicated that although the physical burden experienced by patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis is significant, non-physical domains such as social and mental areas are also impacted to a similar extent16. Similarly, van Ee’s et al.59 recently published a definition of ‘freedom from disease’ including five domains: QoL and well-being, healthcare team support, treatment, psychosocial elements, and management of clinical symptoms.

The present study presents several limitations inherent to the Delphi methodology. Firstly, the inclusion of patients with psoriasis on the Delphi panel may be limiting, despite also representing one of the study’s main strengths. Patients included in the Delphi panel were members of the Spanish patient association (Acción Psoriasis), and therefore they may have an extensive history and strong awareness of their disease. In addition, the Delphi methodology may be challenging for some patients, positioning some of them in the neutral zone. Secondly, even though the consensus threshold was established at the beginning of the study according to recommendations, using another cut-off could give rise to different results. Finally, the study was conducted in Spain; therefore, although the concept of well-being is universal and no major differences are expected in other settings, the results should be interpreted in the Spanish context.

In conclusion, the concept of well-being in psoriasis integrates four dimensions, emotional, physical, social and satisfaction with disease management. All these dimensions and their components reflect patients’ needs and concerns that impact on their daily lives. Therefore, addressing well-being components in psoriasis management will optimise it, contributing to obtaining better outcomes and restoring normalcy to the patients’ life. Future work could evaluate the weight of each of the components and assess differences based on variables.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Obradors, M., Blanch, C., Comellas, M., Figueras, M. & Lizan, L. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis: A systematic review of the European literature. Qual. Life Res. 25(11), 2739–2754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1321-7 (2016).

Rousset, L. & Halioua, B. Stress and psoriasis. Int. J. Dermatol. 57(10), 1165–1172. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.14032 (2018).

Stewart, T. J., Tong, W. & Whitfeld, M. J. The associations between psychological stress and psoriasis: A systematic review. Int. J. Dermatol. 57(11), 1275–1282. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.13956 (2018).

Slomian, A., Lakuta, P., Bergler-Czop, B. & Brzezinska-Wcislo, L. Self-esteem is related to anxiety in psoriasis patients: A case control study. J. Psychosom. Res. 114, 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.005 (2018).

Jankowiak, B., Kowalewska, B., Krajewska-Kulak, E. & Khvorik, D. F. Stigmatization and quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Dermatol. Ther. 10(2), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-020-00363-1 (2020).

Wheeler, M., Guterres, S., Bewley, A. P. & Thompson, A. R. An analysis of qualitative responses from a UK survey of the psychosocial wellbeing of people with skin conditions and their experiences of accessing psychological support. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 47(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.14815 (2022).

Leino, M., Mustonen, A., Mattila, K., Koulu, L. & Tuominen, R. Perceived impact of psoriasis on leisure-time activities. Eur. J. Dermatol. 24(2), 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1684/ejd.2014.2282 (2014).

Tadros, A. et al. Psoriasis: Is it the tip of the iceberg for the quality of life of patients and their families?. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 25(11), 1282–1287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03965.x (2011).

World Health Organization (WHO). Global report on psoriasis 2016 [11/01/2023]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204417/9789241565189_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Villacorta, R. et al. A multinational assessment of work-related productivity loss and indirect costs from a survey of patients with psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 183(3), 548–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.18798 (2020).

Reid, C. & Griffiths, C. E. M. Psoriasis and treatment: Past, present and future aspects. Acta Derm. Venereol. 100(3), adv00032. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-3386 (2020).

Fortune, D. G. et al. Successful treatment of psoriasis improves psoriasis-specific but not more general aspects of patients’ well-being. Br. J. Dermatol. 151(6), 1219–1226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06222.x (2004).

Upton, D., Upton, P. Quality of life and well-being. Psychol. Wounds Wound Care Clin. Pract. 85–111 (2015).

Mrowietz U, Reich K. Psoriasis—new insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 106(1–2), 11–8, quiz 9 (2009). https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2009.0011.

Zhang, H., Yang, Z., Tang, K., Sun, Q. & Jin, H. Stigmatization in patients with psoriasis: A mini review. Front. Immunol. 12, 715839. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.715839 (2021).

Prignano, F. et al. Sharing patient and clinician experiences of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: A nationwide italian survey and expert opinion to explore barriers impacting upon patient wellbeing. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11102801 (2022).

Sommer, R. et al. Implementing well-being in the management of psoriasis: An expert recommendation. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 38(2), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.19567 (2024).

Naughton, M., Shumaker, S., Anderson, R., Czajkowski, S. Psychological aspects of health-related quality of life measurement: Test and scales. In Quality of Life and Pharmaco Economics in Clinical Trials (ed. Lippincott-Raven) 117–131 (1996).

DeWeerdt, S. An emotional response. Nature 492, S62–S63 (2012).

Schuster, B. et al. Happiness in dermatology: A holistic evaluation of the mental burden of skin diseases. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 34(6), 1331–1339. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16146 (2020).

World Health Organization (WHO). Documentos básicos—Constitución de la Organización mundial de la salud—Suplemento de la 48ª edición 2014 [24/01/2023]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/PDF/bd48/basic-documents-48th-edition-sp.pdf.

Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC). Health-related Quality of Life—Well-being concepts [11/01/2023]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/wellbeing.htm.

Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, A., Matz, S. & Huppert, F. A. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y (2020).

Salvador-Carulla, L., Lucas, R., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. & Miret, M. Use of the terms “Wellbeing” and “Quality of life” in health sciences: A conceptual framework. Eur. J. Psychiat. 28(1), 50–65 (2014).

OECD. OECD Guidelines on measuring subjective well-being: OECD Publishing; 2013 [11/01/2023]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264191655-en.pdf?expires=1673439384&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=621B196C5A91335F1D7636FA750EFDCA.

World Health Organization (WHO). Measurement of and target-setting for well-being: an initiative by the WHO Regional Office for Europe 2012 [11/01/2023]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/107309/9789289002912-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Lindert, J., Bain, P. A., Kubzansky, L. D. & Stein, C. Well-being measurement and the WHO health policy Health 2010: Systematic review of measurement scales. Eur. J. Public Health. 25(4), 731–740. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku193 (2015).

Ministerio de la presidencia rclcymd. Real decreto 957/2020, de 3 de noviembre, por el que se regulan los estudios observacionales con medicamentos de uso humano 2020 [08/09/2023]. Available from: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2020-14960.

Grupo de trabajo de los CEIMs con la AEMPS. Memorando de colaboración entre los Comités de ética de la investigación con medicamentos para la evaluación y gestión de los Estudios Observacionales con Medicamentos 2021 [08/09/2023]. Available from: https://www.aemps.gob.es/investigacionClinica/medicamentos/docs/estudios-PA/Memorando_CEIMS.pdf.

Reguant-Álvarez, M. & Torrado-Fonseca, M. El método Delphi. REIRE Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació 9(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1344/reire2016.9.1916 (2016).

Hsu, C. C. & Sandford, B. A. The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. Evaluat. https://doi.org/10.7275/pdz9-th90 (2007).

Thangaratinam, S. & Redman, C. W. E. The Delphi technique. Obstet. Gynaecol. 7, 120–125 (2005).

Birko, S., Dove, E. S. & Ozdemir, V. Evaluation of nine consensus indices in Delphi foresight research and their dependency on Delphi survey characteristics: A simulation study and debate on Delphi design and interpretation. PLoS One 10(8), e0135162. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135162 (2015).

Pozo, M. T., Gutiérrez, J. & Sabiote, C. El uso del método Delphi en la definición de los criterios para una formación de calidad en animación sociocultural y tiempo libre. Rev. Investig. Educ. 25(2), 351–366 (2007).

Diamond, I. R. et al. Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67(4), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 (2014).

Madrid Álvarez, M. B., Carretero Hernández, G., González Quesada, A. & González Martín, J. M. Measurement of the psychological impact of psoriasis on patients receiving systemic treatment. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. (Engl. Ed). 109(8), 733–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adengl.2018.07.009 (2018).

Reich, A., Hrehorow, E. & Szepietowski, J. C. Pruritus is an important factor negatively influencing the well-being of psoriatic patients. Acta Derm. Venereol. 90(3), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-0851 (2010).

Tribo, M. J. et al. Patients with moderate to severe psoriasis associate with higher risk of depression and anxiety symptoms: Results of a multivariate study of 300 spanish individuals with psoriasis. Acta Derm. Venereol. 99(4), 417–422. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-3114 (2019).

Pujol, R. M. et al. Mental health self-assessment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: An observational, multicenter study of 1164 patients in Spain (the VACAP Study). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 104(10), 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2013.04.014 (2013).

Ros, S., Puig, L. & Carrascosa, J. M. Cumulative life course impairment: The imprint of psoriasis on the patient’s life. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 105(2), 128–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2013.02.009 (2014).

Elmets, C. A. et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 80(4), 1073–1113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058 (2019).

Gonzalez-Parra, S. & Dauden, E. Psoriasis and depression: The role of inflammation. Actas Dermosifiliogr. (Engl. Ed.) 110(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2018.05.009 (2019).

Nazik, H., Nazik, S. & Gul, F. C. Body image, self-esteem, and quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 8(5), 343–346. https://doi.org/10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_503_15 (2017).

Rosinska, M., Rzepa, T., Szramka-Pawlak, B. & Zaba, R. Body image and depressive symptoms in person suffering from psoriasis. Psychiatr. Pol. 51(6), 1145–1152. https://doi.org/10.12740/PP/68948 (2017).

Liluashvili, S. & Kituashvili, T. Dermatology life quality index and disease coping strategies in psoriasis patients. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 36(4), 419–424. https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2018.75810 (2019).

Lebwohl, M. G. et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: Results from the population-based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis survey. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 70(5), 871–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.018 (2014).

Ljosaa, T. M., Mork, C., Stubhaug, A., Moum, T. & Wahl, A. K. Skin pain and skin discomfort is associated with quality of life in patients with psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 26(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04000.x (2012).

Böhm, D. et al. Perceived relationships between severity of psoriasis symptoms, gender, stigmatization and quality of life. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 27(2), 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04451.x (2013).

Nowowiejska, J. et al. The assessment of risk and predictors of sleep disorders in patients with psoriasis—A questionnaire-based cross-sectional analysis. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040664 (2021).

Gupta, M. A., Simpson, F. C. & Gupta, A. K. Psoriasis and sleep disorders: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 29, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.09.003 (2016).

Yeroushalmi, S. et al. Psoriasis and exercise: A review. Psoriasis 12, 189–197. https://doi.org/10.2147/PTT.S349791 (2022).

Gisondi, P. et al. Mild cognitive impairment in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. Dermatology 228(1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1159/000357220 (2014).

Pankowski, D., Wytrychiewicz-Pankowska, K. & Owczarek, W. Cognitive impairment in psoriasis patients: A systematic review of case-control studies. J. Neurol. 269(12), 6269–6278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-022-11317-2 (2022).

Belinchon, I. et al. Management of psoriasis during preconception, pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding: A consensus statement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. (Engl. Ed.) 112(3), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2020.10.002 (2021).

Duarte, G. V., Calmon, H., Radel, G. & de Fatima Paim de Oliveira, M. Psoriasis and sexual dysfunction: Links, risks, and management challenges. Psoriasis 8, 93–99. https://doi.org/10.2147/PTT.S159916 (2018).

Sánchez, M. et al. El impacto psicosocial de la psoriasis. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 94(1), 11–16 (2003).

Dauden, E., Conejo, J. & Garcia-Calvo, C. Physician and patient perception of disease severity, quality of life, and treatment satisfaction in psoriasis: An observational study in Spain. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 102(4), 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2010.04.018 (2011).

Florek, A. G., Wang, C. J. & Armstrong, A. W. Treatment preferences and treatment satisfaction among psoriasis patients: A systematic review. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 310(4), 271–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-018-1808-x (2018).

van Ee, I. et al. Freedom from disease in psoriasis: A Delphi consensus definition by patients, nurses and physicians. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 36(3), 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17829 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants in the Delphi Rounds and Spanish patients’ advocacy groups Acción Psoriasis, without them this project would not have been possible.

Funding

The project was funded by Almirall SA. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by Marta Comellas and Luís Lizán. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Marta Comellas and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

ED has the following conflict of interests: Advisory Board member, consultant, grants, research support, participation in clinical trials, honorarium for speaking, research support, with the following pharmaceutical companies: Abbvie/Abbott, Almirall, Amgen-Celgene, Janssen-Cilag, Leo-Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, MSD-Schering-Plough, Lilly, UCB, Brystol-Myers and Boehringer-Ingelheim. IB acted as a consultant and/or speaker for and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by companies that manufacture drugs used for the treatment of psoriasis, including Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Almirall SA, Lilly, AbbVie, Novartis, Celgene, Biogen, Amgen, Leo-Pharma, UCB, Pfizer-Wyeth, and MSD. ECG has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Amgen and Abbvie, and has received support for attending meetings and/or travels from UCB pharma. PC has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscripts writing or educational events from Almirall, Abbvie, Amgen-Celgene, Sanofi. PDLC has received consulting fees or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus manuscript writing or educational events or support for attending meetings and/or travel or has participated on Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board from Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer, Celgene, Janssen., LEO Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi and UCB. SR has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus manuscript writing or educational events from Almirall, Abbvie, Leo Pharma, Lilly, UCB, Novartis, BMS, Boehringer. LL and MC work for an independent research entity that received funding from Almirall to coordinate and conduct the project. FG, ER, JLP and RRV declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Daudén, E., Belinchón, I., Colominas-González, E. et al. Defining well-being in psoriasis: A Delphi consensus among healthcare professionals and patients. Sci Rep 14, 14519 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64738-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64738-6

- Springer Nature Limited