Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of feeding patterns during the first 6 months on weight development of infants ages 0–12 months. Using monitoring data from the Maternal and Child Health Project conducted by the National Center for Women and Children’s Health of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention from September 2015 to June 2019, we categorized feeding patterns during the first 6 months as exclusive breastfeeding, formula feeding, or mixed feeding. We calculated weight-for-age Z scores (WAZ) according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2006 Child Growth Standard using WHO Anthro version 3.2.2. A multilevel model was used to analyze the effect of feeding patterns during the first 6 months on the WAZ of infants ages 0–12 months in monitoring regions. Length of follow-up (age of infants) was assigned to level 1, and infants was assigned to level 2. Characteristics of infants, mothers, and families and region of the country were adjusted for in the model. The average weight of infants ages 0–12 months in our study (except the birth weights of boys who were formula fed or mixed fed) was greater than the WHO growth standard. After we adjusted for confounding factors, the multilevel model showed that the WAZ of exclusively breastfed and mixed-fed infants were statistically significantly higher than those of formula-fed infants (coefficients = 0.329 and 0.159, respectively; P < 0.05), and there was a negative interaction between feeding patterns and age (both coefficients = − 0.020; P < 0.05). Infants who were exclusively breastfed were heavier than formula-fed infants from birth until 12 months of age. Mixed-fed infants were heavier than formula-fed infants before 8 months, after which the latter overtook the former. Infants’ weight development may be influenced by feeding patterns during the first 6 months. Exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months may be beneficial for weight development of infants in infancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

Since early 2000s, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among children has increased sharply in China with the Chinese diet habits and lifestyle changing. According to the figure derived from the World Health Organization (WHO), there was a dramatic increase by 30% in overweight and obesity of those aged under 5 years from 2000 to 20201. Furthermore, Childhood obesity may track into adulthood and increase the risk of type 2 Diabetes, hypertension or other chronic diseases in later life, which is difficult to reverse and bring considerable burden to patients, their families and society2. Therefore, how to prevent and control the overweight and obesity during childhood phase has become an urgent public health problem in China3.

Early life, especially infancy, is a critical period for growth and development. It is well known that breast milk is the best source of nutrients for newborns. The bioactivity in breast milk (e.g., human milk oligosaccharides) protects infants against diarrhea, pneumonia, and other infectious diseases and reduces infant mortality4,5. In addition, breastfeeding may reduce the incidence of breast cancer and ovarian cancer among mothers6,7. Improving breastfeeding worldwide could save the lives of more than 82,000 children younger than 5 years old as well as prevent the deaths of 20,000 mothers from breast cancer each year8. Furthermore, breastfeeding plays an important role in narrowing the gap between rich and poor regions9. Therefore, breastfeeding has been promoted all around the world in recent years. The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF recommend exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months of age, with continued breastfeeding to 2 years of age or beyond10. Nevertheless, because of insufficient breast milk, physical disease in the mother, or concerns about nutrition or other factors, the use of formula to supplement or substitute for breast milk11,12,13 is a universal phenomenon in China.

Body weight is one of the most sensitive and important parameters reflecting the nutritional status and health of infants. Weight-for-age Z scores (WAZ) can be calculated to reflect growth status according to the WHO standard for children with an optimal environment for growth14,15. Although several studies have focused on the influence of breastfeeding on the physical growth of infants, the relationship between feeding patterns and the weight/WAZ of infants is inconsistent and unclear. A previous study reported that infants who were exclusively breastfed were heavier than mixed-fed infants from birth until 12 months of age16, whereas other research showed that mixed-fed and formula-fed infants were heavier than exclusively breastfed infants after 6 months17,18,19. Finally, a longitudinal study in China showed no significant difference in WAZ between exclusively breastfed and formula-fed infants before 6 months after matching on covariates20.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the effects of feeding patterns during the first 6 months on weight development of infants ages 0–12 months to provide data for promoting nutrition and the health of infants.

Methods

Setting

Data used in this study were from the Maternal and Child Health Monitoring Project conducted by the National Center for Women and Children’s Health of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention from September 2015 to June 2019. In the project, five districts in four provinces (Hebei, Liaoning, Fujian, and Hunan) were selected as monitoring sites. These districts were selected based on their good compliance and their existing management systems for child health according to the requirements of the National Basic Public Health Service Project covering the whole area. Pregnant women in their third trimester were recruited as participants, and their children were followed for 3 years. To be included in the study, pregnant women had to (1) have a gestational age between 28 and 36 weeks, (2) have a singleton birth, (3) live in the monitoring site for more than half a year or be a member of the registered population, (4) expect to live in the monitoring site until their child was 3 years of age and present their child to receive routine child health care, (5) have an established handbook of maternal health care with complete records of antenatal examination, and (6) agree to participate in the entire follow-up and provide informed consent. Pregnant women with mental illness or brain disease were excluded. Ultimately, a total of 2731 mother–infant pairs were included in this project.

Participants

Study subjects were 2731 infants in the aforementioned project ages 0–12 months. To ensure homogeneity of infant growth and development, 297 infants were excluded based on gestational age of delivery < 37 weeks (n = 97), neonatal asphyxia (n = 20), birth defects (n = 10), low birth weight (n = 35), or macrosomia (n = 135). An additional 45 infants were excluded because of missing information on breastfeeding. Ultimately 2389 eligible infants contributed to this study.

Data collection

Anthropometric measurements

Infants’ birth length and birth weight were both obtained from midwifery institutions. Data on length and weight were collected by specially trained investigators at five follow-up time points (ages 1, 3, 6, 8, and 12 months). The investigators complied with the requirements of the National Basic Public Health Service Standards.

Questionnaire

A questionnaire was designed and revised several times by experts at the National Center for Women and Children’s Health. Data on characteristics of mothers and families, such as sociodemographic characteristics and diet and lifestyle during pregnancy, were collected by investigators in face-to-face interviews with pregnant women in their third trimester. Information on infants, such as sociodemographic characteristics and feeding status, was acquired by investigators at face-to-face physical examinations of infants at three follow-up time points (ages 1, 6, and 12 months) at the same time.

Calculation of Z scores

WHO Anthro version 3.2.2 was used to calculate WAZ according to infants’ gender, age, and weight measurements.

Definition of feeding patterns during the first 6 months

Based on feeding information obtained by the Maternal and Child Health Monitoring Project at 6 months, feeding patterns of infants during the first 6 months were classified into three types: exclusive breastfeeding (i.e., infants were not weaned or given any other drink, except water, or any complementary foods at 6 months), formula feeding (i.e., infants were not breastfed at 6 months), or mixed feeding (i.e., infants received both breast milk and formula at 6 months).

Covariates

We controlled for potential confounders that may be related to the physical growth and development of infants, including characteristics of infants (including gender, birth weight, and timing for starting complementary foods), characteristics of mothers and families (including maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index [BMI], maternal education, paternal BMI, and annual family income), and region of the country. The timing for starting complementary food was classified as ≤ 6 months or > 6 months. Based on guidelines for the prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults21, both maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and paternal BMI were divided into three classes: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–23.9 kg/m2), and overweight/obese (≥ 24.0 kg/m2). Maternal education was classified as less than college or college or higher. Annual family income was categorized as < 4107 dollars or ≥ 4107 dollars. Region of the country was categorized as northern or southern China.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables are presented as frequencies and proportions (%). The chi-square test and t test were used to compare baseline characteristics between boys and girls.

Construction of a multilevel model

Multilevel models, also called “random effect models,” “random coefficient models,” and “mixed-effects models,” show the inherent connections and time-varying regularity of research characteristics in the same subject across different follow-up points. They also show interactions between influencing factors (research variables and other confounders) and time. In addition, these models allow the use of data in unbalanced designs with different follow-up intervals or times or missing data at follow-up points22. For this reason they have been widely used to deal with unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data in the field of the growth and development of children23,24,25. Therefore, we used a two-level growth model to analyze the association between feeding patterns during the first 6 months and the WAZ of infants ages 1–12 months. Length of follow-up (age of infants) was assigned to level 1, and infants was assigned to level 2. We took the WAZ of infants ages 1, 3, 6, 8, and 12 months as the outcome variable; age (length of follow-up), feeding patterns, and the interaction between age and feeding patterns as fixed effects; and age and infants as random effects. Because there is a nonlinear relationship between age and WAZ, a polynomial of time was added to the model. (The model was best-fitted when fixed coefficient of age was up to and including the cubic term and random coefficient at level 2 was liner according to Akaike’s information criterion and the Bayesian information criterion, χ2 = 8932.33, P < 0.05; Akaike’s information criterion and the Bayesian information criterion were 22,219.60 and 22,242.70, respectively.) All data analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

The Maternal and Child Health Monitoring Project was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Center for Women and Children’s Health, China CDC (record no. FY2015-012). All of pregnant woman signed informed consent before enrollment. And all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study subjects

Among the 2389 infants included in this study, there were slightly more boys (52.53%) than girls (47.47%); the ratio was about 1.11:1.00. The birth weight and birth length of boys were significantly greater than those of girls. Most (69.82%) infants were mixed fed during the first 6 months; 16.12% and 14.06% of infants were exclusively breastfed and formula fed, respectively, during the first 6 months. About 80% of infants received complementary food before 6 months. The average delivery age was 28.80 years. Moreover, 19.62% and 17.18% of mothers were underweight and overweight/obese, respectively; 4.86% and 44.76% of fathers were underweight and overweight/obese, respectively. The majority of mothers had less than a college education. Among the majority of families, the annual family income was more than 30,000 yuan. Finally, 56.43% and 43.57% of infants lived in the north and south of the country, respectively (Table 1).

The weight development of infants ages 0–12 by feeding pattern

As shown in Table 2, the average weight of infants ages 0–12 months in our study (except the birth weights of boys who were formula fed or mixed fed) was greater than the WHO growth standard.

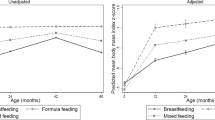

As shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4, the weight/WAZ of exclusively breastfed infants at the five follow-up points (except boys age 12 months) were higher than those of formula-fed and mixed-fed infants according to the anthropometric data.

The association between feeding patterns and the WAZ of infants ages 0–12 months

As shown in Table 3 after we adjusted for confounding factors, the multilevel model showed that the WAZ of exclusively breastfed and mixed-fed infants were statistically significantly higher than those of formula-fed infants (coefficients = 0.329 and 0.159, respectively), and there was a negative interaction between feeding patterns and age (both coefficients = − 0.020; P < 0.05). Infants who were exclusively breastfed were heavier than formula-fed infants from birth to 12 months of age. Mixed-fed infants were heavier than formula-fed infants before 8 months, after which the latter overtook the former.

Moreover, infant birth weight was positively associated with WAZ, which increased by about 1.216 units for every 1-unit increase in birth weight. The WAZ of girls were higher than those of boys. The WAZ of infants in northern China were higher than those of infants in southern China. Compared to infants who started complementary food before 6 months, infants who started after 6 months had lower WAZ. Infants were more likely to have lower WAZ if their mothers were underweight and were more likely to have higher WAZ if their fathers were overweight/obese. Infants whose mothers had a college education or higher had higher WAZ compared to infants whose mothers had less than a college education (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study shows that breastfeeding is the main feeding pattern during the first 6 months in these monitoring regions. However, the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding is quite low. The 2013 Chinese National Nutrition and Health Survey showed that the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding before 6 months was only 20.7%26, which is consistent with this study. This suggests that health guidelines and education should continue to be strengthened in monitoring regions to reduce the use of and dependence on formula and increase the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding within the first 6 months of age.

The average weight of infants at the five follow-up time points in our study was greater than the WHO standard, which demonstrates that infants with all three feeding patterns can achieve good growth, a result also found in other Chinese research27,28. The WAZ-curve declined after 8 months for all feeding patterns, which are consistent with previous research29. This suggests that with the rapid economic development and improvement in living conditions, as well as effective actions for the promotion of breastfeeding have been taken in recent years, infants in early infancy are in a good physical growth status. However, the inappropriate complementary feeding behavior (e.g., complementary foods with a poor nutritional quality) is very common in rural and urban in China, which may associate with lower growth velocity of infants30,31.

The multilevel model in this study showed a positive association between exclusive breastfeeding or mixed feeding and weight development of infants. However, a negative interaction between feeding patterns and age was observed at the same time. This suggests that breastfeeding is beneficial for weight development of infants, especially in early infancy, although complementary food should replace human breast milk and become the main source of nutrients for infants as they age32. Thus, great attention should be paid to the timely and scientific addition of complementary food, while breastfeeding should be promoted in the meantime. Our findings show that infants who were exclusively breastfed were heavier than formula-fed infants from birth to 12 months of age, which might imply that exclusive breastfeeding before 6 months promotes infants’ physical growth and development better compared to formula that gradually improving its nutritional composition and ratio of nutrient. Similar findings have been reported in previous research carried out by Eriksen et al. in Gambia16, Kuchenbecker et al. in Malawi33, and Wright et al. in The Philippines34. Previous research has determined that breast milk contains rich nutrients and compared to formula is better absorbed to satisfy the nutritional requirements of infants35,36. The majority content of essential components in commercial infant formulas in China adequate the new national standard requirements, however, a few essential nutrient (e.g., vitamin D) in the formula products cannot meet with the new national standard requirements37.There were significant differences in the content and stereochemical structure of Triacylglycerols (TAGs) between commercial infant formulas and breast milk38. Moreover, exclusive breastfeeding may protect infants against gastrointestinal, respiratory, and other infections, enhance maternal-infant attachment, and contribute to facilitate the consumption of more vegetables in later childhood in obesity prone normal weight children39,40. A study in Belarus reported that breastfeeding infants who were lighter at a previous visit were significantly more likely to have been weaned by a subsequent visit, especially at 2–6 months of age, which suggests that the growth status of infants may also affect feeding behaviors41.

In addition, our study found associations between gender, birth weight, paternal BMI, complementary food, and region of the country and the WAZ of infants. Our findings are consistent with previous research42,43.These may indicate that different regions may difference in lifestyle habits, eating habits and customs, and the growth and development of infants result from a combination of genetic, geographic, nutritional, and other environmental factors. It is difficult to change genetic and geographic factors, and therefore persistent exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months may be of great importance to promoting weight growth of infants.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations. Our study was conducted in five monitoring sites in four provinces of China, and thus the results cannot be generalized to China as a whole. The classification of feeding patterns during the first 6 months was based on feeding information collected at a follow-up point (6 months of age), which may have affected the feeding rate. In addition, some research suggests that complementary food should be added at 4–6 months of age. However, the definition of exclusive breastfeeding in this study was that infants were not given any complementary foods at 6 months, and thus the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in this study may have been low. Furthermore, this multilevel model adjusted for only the timing for starting complementary food, not the types or frequency of complementary food. Besides, amount of sleep and other lifestyle factors that may affect the growth of infants were not considered, which may have affected the accuracy of the results. Finally, compared to WAZ, weight-for-length Z scores (WLZ) can better reflect the nutritional status of infants by controlling for the influence of length on weight, so the associations between feeding patterns and WLZ after adjusting for characteristics of infants, mothers, and families and region of the country need to be further studied in the future.

Conclusions

Infants’ weight development may be influenced by different feeding patterns during the first 6 months. Exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months is beneficial for weight development of infants in infancy. It is difficult to change genetic and geographic factors, and therefore persistent exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months may be of great importance to promoting weight development of infants.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the protection for the privacy of participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WAZ:

-

Weight-for-age Z score

- WLZ:

-

Weight-for-length Z score

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- AIC:

-

Akaike’s information criterion

- BIC:

-

Bayesian information criterion

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SE:

-

Standard error

References

World Health Organization. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates: Key findings of the 2021 edition. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025257. Accessed 15 Mar 2023.

Lanigan, J. Prevention of overweight and obesity in early life. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 77(3), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665118000411 (2018).

Yang, B. et al. Child nutrition trends over the past two decades and challenges for achieving nutrition SDGs and National targets in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(4), 1129 (2020).

Andreas, N. J., Kampmann, B. & Mehring, L. K. Human breast milk: A review on its composition and bioactivity. Early Hum. Dev. 91(11), 629–635 (2015).

Lyons, K. E., Ryan, C. A., Dempsey, E. M., Ross, R. P. & Stanton, C. Breast milk, a source of beneficial microbes and associated benefits for infant health. Nutrients 12(4), 1039 (2020).

Babic, A. et al. Association between breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk. JAMA Oncol. 6(6), e200421 (2020).

Anstey, E. H. et al. Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk reduction: Implications for black mothers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 53(3S1), S40–S46 (2017).

Victora, C. G. et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 387(10017), 475–490 (2016).

Rollins, N. C. et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices?. Lancet 387(10017), 491–504 (2016).

World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding. Accessed 20 Jun 2022.

Shi, H. et al. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months in China: A cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 16(1), 40 (2021).

Monge-Montero, C. et al. Mixed milk feeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis of its prevalence and drivers. Nutr. Rev. 78(11), 914–927 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Breastfeeding in China: A review of changes in the past decade. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(21), 8234 (2020).

World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924154693X. Accessed 20 Jun 2022.

Yang, Z. et al. Comparison of the China growth charts with the WHO growth standards in assessing malnutrition of children. BMJ Open 5(2), e6107 (2015).

Eriksen, K. G. et al. Following the World Health Organization’s recommendation of exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months of age does not impact the growth of rural Gambian infants. J. Nutr. 147(2), 248–255 (2017).

Kupers, L. K. et al. Determinants of weight gain during the first two years of life-the GECKO Drenthe birth cohort. PLoS One 10(7), e133326 (2015).

Agostoni, C. et al. Growth patterns of breast fed and formula fed infants in the first 12 months of life: an Italian study. Arch. Dis. Child 81(5), 395–399 (1999).

Kramer, M. S. et al. Breastfeeding and infant growth: Biology or bias?. Pediatrics 110(2 Pt 1), 343–347 (2002).

Fang, Y. et al. Associations between feeding patterns and infant health in China: A propensity score matching approach. Nutrients 13(12), 4518 (2021).

Obesity Working Group of China. Guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. ACTA Nutr. Sin. 26(1), 1–4 (2004).

Goldstein, H., Healy, M. J. & Rasbash, J. Multilevel time series models with applications to repeated measures data. Stat. Med. 13(16), 1643–1655 (1994).

Goldstein, H., Browne, W. & Rasbash, J. Multilevel modelling of medical data. Stat. Med. 21(21), 3291–3315 (2002).

Luo, H. et al. Growth in syphilis-exposed and -unexposed uninfected children from birth to 18 months of age in China: A longitudinal study. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 4416 (2019).

Johnson, B. A. et al. Multilevel analysis of the be active eat well intervention: Environmental and behavioural influences on reductions in child obesity risk. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 36(7), 901–907 (2012).

Duan, Y. et al. Exclusive breastfeeding rate and complementary feeding indicators in China: A National representative survey in 2013. Nutrients 10(2), 249 (2018).

Ouyang, F. et al. Growth patterns from birth to 24 months in Chinese children: A birth cohorts study across China. BMC Pediatr. 18(1), 344 (2018).

Zhang, Y. Q. et al. The 5th national survey on the physical growth and development of children in the nine cities of China: Anthropometric measurements of Chinese children under 7 years in 2015. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 163(3), 497–509 (2017).

Tian, Q. et al. Differences between WHO growth standards and China growth standards in assessing the nutritional status of children aged 0–36 months old. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(1), 251 (2019).

Sirkka, O., Abrahamse-Berkeveld, M. & van der Beek, E. M. Complementary feeding practices among young children in China, India, and Indonesia: A narrative review. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 6(6), nzac092. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzac092 (2022).

Zhang, J., Shi, L., Chen, D. F., Wang, J. & Wang, Y. Effectiveness of an educational intervention to improve child feeding practices and growth in rural China: Updated results at 18 months of age. Matern. Child Nutr. 9(1), 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00447.x (2013).

D’Auria, E. et al. Complementary feeding: Pitfalls for health outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(21), 7931 (2020).

Kuchenbecker, J. et al. Exclusive breastfeeding and its effect on growth of Malawian infants: Results from a cross-sectional study. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 35(1), 14–23 (2015).

Wright, M. J. et al. The interactive association of dietary diversity scores and breast-feeding status with weight and length in Filipino infants aged 6–24 months. Public Health Nutr. 18(10), 1762–1773 (2015).

Martin, C. R., Ling, P. R. & Blackburn, G. L. Review of infant feeding: Key features of breast milk and infant formula. Nutrients 8(5), 279 (2016).

Ahern, G. J. et al. Advances in infant formula science. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 10, 75–102 (2019).

Liu, S. N. et al. Comparative study on the essential composition content of commercial infant formula with the requirements in the new national food safety standard in China from 2017 to 2022. J. Hyg. Res. 52(03), 389–393 (2023).

Sun, C. et al. Evaluation of triacylglycerol composition in commercial infant formulas on the Chinese market: A comparative study based on fat source and stage. Food Chem. 252, 154–162 (2018).

Hossain, S. & Mihrshahi, S. Exclusive breastfeeding and childhood morbidity: A narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(22), 14804 (2022).

Specht, I. O., Rohde, J. F., Olsen, N. J. & Heitmann, B. L. Duration of exclusive breastfeeding may be related to eating behaviour and dietary intake in obesity prone normal weight young children. PLoS One 13(7), e0200388 (2018).

Kramer, M. S. et al. Breastfeeding and infant size: Evidence of reverse causality. Am. J. Epidemiol. 173(9), 978–983 (2011).

Zhang, J. et al. Birth weight, growth and feeding pattern in early infancy predict overweight/obesity status at two years of age: A birth cohort study of Chinese infants. PLoS One 8(6), e64542 (2013).

Quyen, P. N. et al. Effect of maternal prenatal food supplementation, gestational weight gain, and breast-feeding on infant growth during the first 24 months of life in rural Vietnam. PLoS One 15(6), e233671 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the support of the administrators, child health physicians, and investigators in the five monitoring regions and greatly appreciate the support of all the families that participated in this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The data analysis and writing of the manuscript were completed by C.Z. Data quality control was performed by W.Z. and A.H., X.P. and A.H. reviewed the first draft of the manuscript and helped with revisions. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be held accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Cy., Zhao, W., Pan, Xp. et al. Effects of feeding patterns during the first 6 months on weight development of infants ages 0–12 months: a longitudinal study. Sci Rep 14, 17451 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58164-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58164-x

- Springer Nature Limited