Abstract

The study aimed to investigate the association between long-term sedentary behavior (LTSB) and depressive symptoms within a representative sample of the U.S. adult population. Data from NHANES 2017–2018 were used, encompassing information on demographics, depressive symptoms, physical activity (PA), and LTSB. Depressive symptoms were identified using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), with “depressive symptoms” defined as a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 5, and “moderate to severe depressive symptoms (MSDS)” defined as a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10. PA and LTSB were assessed through the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire, where LTSB was interpreted as sedentary time ≥ 600 min. Restricted Cubic Spline (RCS) curves were utilized to observe potential nonlinear relationships. Binary Logistic regressions were conducted to analyze the associations. A total of 4728 participants (mean age 51.00 ± 17.49 years, 2310 males and 2418 females) were included in the study. Among these individuals, 1194 (25.25%) displayed depressive symptoms, with 417 (8.82%) exhibiting MSDS. RCS curves displayed increased risk of depressive symptoms with prolonged sedentary duration. Logistic regression models indicated significant associations between LTSB and depressive symptoms (OR 1.398, 95% CI 1.098–1.780), and LTSB and MSDS (OR 1.567, 95% CI 1.125–2.183), after adjusting for covariates. These findings suggest that LTSB may act as a potential risk factor for both depressive symptoms and MSDS in the studied population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental disorders are the major causes of the global health-related burden, with depressive symptoms being the primary contributor to this burden1, which severely affects quality of life2. Depression is also the leading cause of disability worldwide, affecting approximately 280 million people and causing more than 47 million disabilities yearly3. Hasin predicted that the 12-month and lifetime prevalence of depression was 10.4% and 20.6% in Americans4. However, recent surveys suggest that the incidence of depressive symptoms in U.S. adults is increasing5,6. Also with the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic in recent years, risk factors such as economic stress and social isolation have also briefly led to an increase in depressive symptoms7. Given the high prevalence of depressive symptoms and its significant impact on quality of life, it is imperative to identify the risk factors that contribute to its development and implement effective intervention measures.

Physical activity (PA) was previously argued to be strongly associated with depressive symptoms8,9,10. Exercise therapy was shown to have a similar effect as drug therapies for major depression11. PAs are defined as activities that require a metabolic equivalent of more than 1.5 Metabolic Equivalents (METs) during waking hours, while sedentary behavior generally refers to activities that require a metabolic equivalent of less than 1.5 METs12,13. The decrease of PA inevitably lead to the increase of sedentary behavior. World Health Organization suggested that adults aged 18–64 should limit the amount of sedentary time and replace them with aerobic activity to prevent chronic conditions14. The duration of “10 h” has been widely acknowledged as a critical threshold for Long-term sedentary behavior (LTSB)15,16,17. Prolonged sedentary behavior exceeding 10 h can have detrimental effects on human health. A comprehensive review by authoritative sources highlighted that engaging in LTSB significantly increases the risk of chronic diseases and all-cause mortality18. In addition, studies have shown that the negative effect of LTSB was not always offset by the benefits of PA19, and LTSB may be an independent risk factor for some chronic conditions. Therefore, it has started to recognize the impact of LTSB as an independent risk factor for depressive symptoms.

Previous studies demonstrated that LTSB may lead to emotional disorders in university students20, adolescents21,22 and senior citizens23. However, these studies lacked a unified description of the U.S. population, sample size and sample distribution characteristics were generally limited, and the representativeness was also weak. Therefore, a reliable large sample cross-sectional survey in a representative sample of the U.S. adult population is particularly essential.

The aim of this study is to explore the association between LTSB and depressive symptoms through rigorous analysis and evaluation with the samples from a larger population.

Materials and methods

Study population

This study was a cross-sectional survey that followed the STROBE checklist. Participants were sourced from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a population-based cross-sectional survey designed to collect information about the health and nutrition situation of the U.S. household population. A stratified multistage sampling design was used to obtain a representative sample of U.S. residents aged two months and older. The NHANES protocol was approved by the National Center for Health Statistic's esearch ethics review board; all adult participants provided written notice of consent24. And the use of NHANES data as a secondary data source was also approved25. The present study extracted and aggregated data on demographic characteristics, depressive symptoms, PA and LTSB from the NHANES 2017–2018, and the current sample is restricted to adults aged 20 and older.

Depressive symptoms assessment

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a nine-item depression screening instrument, was used to assess the frequency of depression symptoms in the sample over the past 2 weeks. The questions were asked at the Mobile Examination Center (MEC) by trained interviewers using the Computer-Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI) system, which is programmed with built-in consistency checks to reduce data entry errors as part of the MEC interview. For each item, points ranging from 0 to 3, are associated with the response categories "not at all", "several days", "more than half the days", and "nearly every day"26,27. A total score ranging from 0 to 27 can be computed for participants who provide complete responses to the symptom questions. Cut-off points of 5, 10, and 20 are typically used to indicate levels of symptoms severity27. A PHQ-9 score of ≥ 5 is commonly considered indicative of "depressive symptoms" in general28,29. On the other hand, a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10 is recognized as the threshold for "moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms (MSDS)" and serves as a clinical criterion to screen for major depression, indicating the need for intervention30. In this study, we categorized PHQ-9 scores into two criteria: PHQ-9 score ≥ 5 and ≥ 10 to examine the associations between LTSB and "depressive symptoms", and LTSB and "MASD", respectively. Furthermore, the last question of PHQ-9: “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problem: Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way?”, was used to evaluate participants' self-injury tendencies31.

LTSB assessment

Participants’ sedentary duration was assessed through a respondent-level interview using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ)32. The interview was also established in MEC by trained interviewers using the CAPI system. Sedentary duration was assessed through one question: “The following question is about sitting at school, at home, getting to and from places, or with friends, including time spent sitting at a desk, traveling in a car or bus, reading, playing cards, watching television, or using a computer. Do not include time spent sleeping. How much time do you usually spend sitting on a typical day?” The reported sedentary duration was recorded in minutes. For the purpose of this study, sedentary duration > 600 min was categorized as LTSB.

Covariates

The covariates considered in this study include gender, age, race, education, marital status, smoking status, military service, self-injury tendency, body mass index (BMI) status, and PA. These variables were chosen based on their potential associations with specific health risks and experiences, substance use, negative health consequences of obesity, and positive health outcomes resulting from good behavior33,34,35. We have included these covariates as they may impact the primary outcome of our study. Age was divided into three groups: < 40, 40–60, and > 60. Race was divided into five groups: Hispanic, Non-Hispanic white, Non-Hispanic black, Non-Hispanic Asian, and Other. Education was divided into four groups: < 12th grade, high school, some college, college and above. Marital status was classed as married and not married (living with a partner, widowed, divorced, separated, never married). Smoking status was classed as smoking (smoked 100 cigarettes in life) and non-smoking (did not smoke 100 cigarettes in life)36. BMI was measured by trained technicians using standardized equipment during MEC physical examination, and BMI status was categorized into three categories: Underweight (≤ 18.9 kg/m2), Normal weight (19.0–29.9 kg/m2) and Obese (≥ 30.0 kg/m2)37. Considering that different types of PAs affect depression in different directions, we selected two physical activity covariates. The first, work physical activity (OPA), a type of physical activity that promotes the development of depressive symptoms38, and the second, leisure-time physical activity (LTPA), a type of physical activity pair that inhibits the development of depressive symptoms39. Both OPA and LTPA were assessed by the GPAQ and classified into three levels: inactive, moderate and vigorous40.

Statistical analyses

Initially, we aggregated the extracted information, excluded missing and missing or irrelevant data, utilizing Microsoft Excel 2010. Adults aged 20 years and older from the NHANES 2017–18 cycle with complete information on independent variable (LTSB) and dependent variable (depressive symptoms) were included in the analyses.

Subsequently, we employed SPSS 26.0 for conducting descriptive statistics, inter-group comparisons, and binary logistic regression analysis. In the inter-group analysis, we categorized the dependent variables into "depressive group" and "non-depressive group", and assess the variances in independent variable and covariates between the two groups. Categorical variables were evaluated using the chi-square test, while continuous variables were analyzed using the rank-sum test. Logistic regression was carried out to analyze associations between LTSB and depressive symptoms, as well as LTSB and MSDS. Covariates that were statistically significant in the inter-group comparisons were included in the regression models. In order to eliminate the interference of covariates, we have established the following models: Model I: Primary model, without adjusting for any covariates. Model II: Adjusted for the independent variable in Model I plus demographic covariates (gender, race, marital status). Model III: Adjusted the variables in Model II all covariates (plus smoking, LTPA, BMI).

Concurrently, we utilized the R software to generate Restricted Cubic Spline (RCS) curves. The RCS curves were created for "LTSB-Depressive Symptoms" and "LTSB-MSDS," with the dependent variable serving as the horizontal axis, and the odds ratio (OR) along with the 95% confidence interval (CI) representing the vertical axis. This visualization allowed us to investigate potential nonlinearity within these two associations. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (2-sided tests).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocols for NHANES were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Board (Protocol#2017–1). All adult participants provided written notification of consent before participating in the study.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Out of the 5569 participants initially included in the study, 1291 individuals (23.18%) had missing data for LTSB or depression were excluded. Consequently, a total of 4728 adults aged 20 years or older, who participated in the NHANES cycle 2017–2018, were included in the final analysis. The participants had a mean age of 51.00 ± 17.49 years at the time of examination, comprising 2310 males and 2418 females, with an average sedentary duration of 330.61 ± 119.67 min. Significant statistical differences were observed in gender (P < 0.001), age (P = 0.021), race (P = 0.043), marital status (P < 0.001), smoking status (P < 0.001), sedentary duration (P = 0.038), LTSB (P = 0.001), BMI (P < 0.001), self injury tendency (P < 0.001), OPA (P = 0.007) and LTPA (P < 0.001) between the depressive group and the non-depressive group. However, there were no statistically significant differences in military service (P = 0.335) and education (P = 0.068) between the two groups (See Table 1).

Depressive symptoms in the present study

Out of the 4278 participants surveyed, 1194 (25.25%) exhibited depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score ≥ 5). Among the individuals with depressive symptoms, 777 (16.43%) participants demonstrated mild depressive symptoms, whereas the remaining 417 (8.82%) participants exhibited MSDS (PHQ-9 score ≥ 10), which were generally believed requiring interventions.

RCS curves of sedentary duration and depressive symptoms

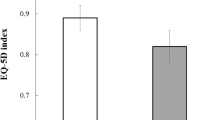

The results revealed that the mean odds ratio (OR) for the association between sedentary duration and depressive symptoms remained below 1 until reaching 600 min, and subsequently exceeded 1 for duration exceeding 600 min. Moreover, the OR increased with longer sedentary duration (see Fig. 1). In the case of the association between sedentary duration and MSDS, the mean OR consistently exceeded 1 and exhibited an upward trend with longer sedentary duration (see Fig. 2).

Logistic regression analyses

In the analysis of the association between LTSB and depressive symptoms, our results revealed a significant positive association. Before adjusting for covariates, participants engaging in LTSB were found to have higher odds of experiencing depressive symptoms (OR 1.484, 95% CI 1.176–1.817). This association remained significant after adjusting for covariates (OR 1.398, 95% CI 1.098–1.780). Specifically, individuals who engaged in sedentary behavior for more than 600 min per day had a 39.8% higher likelihood of developing depressive symptoms (See Table 2).

In the analysis of the association between LTSB and MSDS, our results also revealed a significant positive association. Before adjusting for covariates, participants engaging in LTSB were found to have higher odds of experiencing MSDS (OR 1.697, 95% CI 1.229–1.342). This association remained significant after adjusting for covariates (OR 1.567, 95% CI 1.125–2.183). The results suggest that individuals with LTSB had a rather higher likelihood (56.7%) to develop MSDS (See Table 3).

Discussion

LTSB and depressive symptoms

This study identified a direct association between prolonged sedentary duration and an increased risk of depressive symptoms, indicating that LTSB serves as a potential risk factor for depressive symptoms. In following discussion, we will delve into the reasons why LTSB represents a risk factor for depression across three dimensions: physiological, psychological, and social.

From a physiological standpoint, LTSB impacts physical health in various ways, potentially elevating the risk of depression. Prolonged sitting results in reduced PA levels, impacting cardiovascular health and heightening the susceptibility to heart disease and stroke41. These physical conditions not only affect overall health but may also contribute to mental health issues like low mood and depression. Furthermore, sedentary habits can give rise to poor posture leading to issues such as muscle tension and neck/back pain42, which can further exacerbate or trigger depressive symptoms through somatic pain43.

On a psychological level, LTSB can heighten the risk of depression by influencing an individual’s cognitive and emotional states. Prolonged sedentary duration may induce distraction and decreased productivity44, leading to heightened feelings of stress and anxiety. Additionally, sedentary lifestyles can restrict PA and social interactions, diminishing feelings of enjoyment and fulfillment45, thereby amplifying the likelihood of depression. Furthermore, sedentary patterns may impact an individual's sleep quality46, with restful sleep being crucial for maintaining mental well-being.

At the societal level, LTSB is closely linked with the fast-paced lifestyle and work environments prevalent in modern society. Many occupations necessitate prolonged sitting in front of computers, promoting sedentary habits. This fast-paced lifestyle often deprives individuals of ample opportunities for PA and social engagement, consequently escalating the risk of depression47. Societal perceptions and attitudes towards LTSB may also play a role in mental health outcomes. Certain cultural beliefs may view sedentary behavior as a manifestation of laziness or lack of self-discipline, potentially exerting a detrimental impact on an individual's mental health.

Stronger association between LTSB and MSDS

When analyzing the association between LTSB and depressive symptoms, we observed a stronger association between LTSB and MSDS compared to the association between LTSB and depressive symptoms in general. We attribute this heightened association to the cumulative impact and cyclical nature of LTSB on both physical and mental well-being.

Prolonged sedentary duration often result in diminished PA levels, impacting cardiovascular health, body posture, and sleep quality48. These physical consequences may progressively deteriorate, ultimately leading to more severe health issues, including MSDS. Additionally, LTSB can curtail social interactions and engagement in social activities, reducing feelings of pleasure and satisfaction over time. This psychological state of decline may contribute to the development of MSDS. Furthermore, extended periods of sedentarism can engender negative life patterns, such as decreased motivation and interest49, which can exacerbate depressive symptoms, perpetuating a detrimental cycle.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that MSDS may be linked to more pronounced biological alterations, such as neurotransmitter imbalances and inflammatory responses50. Prolonged sedentary duration has the potential to exacerbate depressive symptoms by influencing these biological processes. A sedentary lifestyle may elevate inflammatory markers in the body, and mounting evidence underscores the significant relationship between inflammation and depressive symptoms51,52.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. Firstly, somatic factors such as diabetes, cancer, and physical disability, which can potentially trigger depressive symptoms, were not included as covariates in our analysis. This omission could have influenced our findings. Secondly, we did not consider the influence of medication use, particularly the use of antidepressants, which could have a significant impact on depressive symptoms. This omission may have affected the observed associations. Thirdly, the small sample size utilized in this study may introduce bias and limit the generalizability of our findings. Future studies could consider including additional covariates and analyzing larger datasets encompassing multiple NHANES cycles of data to enhance the reliability and robustness of the results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that LTSB is an independent risk factor for depressive symptoms in U.S. adults. Sedentary duration exceeding 600 min per day was significantly associated with depressive symptoms, underscoring the role of time in the harmful effects of sedentary duration on mental health. The results indicated that LTSB had a significant impact on depressive symptoms after adjusting for covariates. Furthermore, these associations were particularly strong in cases of moderate to sever depressive symptoms.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the [NHANES] repository, [NHANES Questionnaires, Datasets, and Related Documentation (cdc.gov)]. Raw data supporting the obtained results are available at the corresponding authors.

References

COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398(10312), 1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7 (2021).

Tran, B. X. et al. Global mapping of interventions to improve quality of life of patients with depression during 1990–2018. Qual. Life Res. 29(9), 2333–2343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02512-7 (2020).

Pearce, M. et al. Association between physical activity and risk of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 79(6), 550–559. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0609 (2022).

Hasin, D. S. et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 75(4), 336–346. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602 (2018).

Patel, V. et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from disease control priorities. Lancet 387(10028), 1672–1685. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00390-6 (2016).

Stein, M. B. EDITORIAL: COVID-19 and anxiety and depression in 2020. Depress. Anxiety 37(4), 302. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23014 (2020).

Zhou, F. et al. A randomized trial in the investigation of anxiety and depression in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Ann. Palliat. Med. 10(2), 2167–2174. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-212 (2021).

Kandola, A., Ashdown-Franks, G., Hendrikse, J., Sabiston, C. M. & Stubbs, B. Physical activity and depression: Towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 107, 525–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.040 (2019).

Choi, K. W. et al. Assessment of bidirectional relationships between physical activity and depression among adults: A 2-sample Mendelian randomization study. JAMA Psychiatry 76(4), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4175 (2019).

McMahon, E. M. et al. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and well-being. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 26(1), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0875-9 (2017).

Cooney, G. M. et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013(9), CD004366. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6 (2013).

Sedentary Behaviour Research Network. Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours”. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 37(3), 540–542. https://doi.org/10.1139/h2012-024 (2012).

Ainsworth, B. E. et al. 2011 Compendium of physical activities: A second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43(8), 1575–1581. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12 (2011).

Bull, F. C. et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 54(24), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 (2020).

Healy, G. N., Matthews, C. E., Dunstan, D. W., Winkler, E. A. & Owen, N. Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in US adults: NHANES 2003–06. Eur. Heart J. 32(5), 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq451 (2011).

Rhodes, R. E., Mark, R. S. & Temmel, C. P. Adult sedentary behavior: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 42(3), e3-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.020 (2012).

Stamatakis, E., Hamer, M. & Dunstan, D. W. Screen-based entertainment time, all-cause mortality, and cardiovascular events: Population-based study with ongoing mortality and hospital events follow-up. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57(3), 292–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.065 (2011).

Ekelund, U. et al. Joint associations of accelero-meter measured physical activity and sedentary time with all-cause mortality: A harmonised meta-analysis in more than 44 000 middle-aged and older individuals. Br. J. Sports Med. 54(24), 1499–1506. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-103270 (2020).

Blough, J. & Loprinzi, P. D. Experimentally investigating the joint effects of physical activity and sedentary behavior on depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 15(239), 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.019 (2018).

Lee, E. & Kim, Y. Effect of university students’ sedentary behavior on stress, anxiety, and depression. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 55(2), 164–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12296 (2019).

Chaput, J. P. et al. 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years: Summary of the evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01037-z (2020).

Hoare, E., Milton, K., Foster, C. & Allender, S. The associations between sedentary behaviour and mental health among adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 13(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0432-4 (2016).

Zhai, L., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, D. Sedentary behaviour and the risk of depression: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 49(11), 705–709. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-093613 (2015).

NHANES Ethics Review Process. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm (accessed 14 February 2024).

Protecting Human Participants – NHANES Data. Available online: https://humansubjects.nih.gov/data (accessed 14 February 2024).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-15: Validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom. Med. 64(2), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008 (2002).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Ettman, C. K. et al. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 3(9), e2019686. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686 (2020).

Mo, H. et al. The association of vitamin D deficiency, age and depression in US adults: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Psychiatry 23(1), 534. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04685-0 (2023).

Levis, B., Benedetti, A. & Thombs, B. D. DEPRESsion screening data (DEPRESSD) collaboration. Accuracy of patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: Individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ 365, l1476. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1476 (2019). Erratum in: BMJ 365, l1781 (2019).

Kim, S., Lee, H. K. & Lee, K. Which PHQ-9 items can effectively screen for suicide? Machine learning approaches. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(7), 3339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073339 (2021).

Keating, X. D. et al. Reliability and concurrent validity of global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(21), 4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16214128 (2019).

Greenland, S., Pearl, J. & Robins, J. M. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 10(1), 37–48 (1999).

VanderWeele, T. J. Principles of confounder selection. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 34(3), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00494-6 (2019).

Tennant, P. W. G. et al. Use of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to identify confounders in applied health research: Review and recommendations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 50(2), 620–632. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa213 (2021).

Cao, C. et al. Handgrip strength is associated with suicidal thoughts in men: Cross-sectional analyses from NHANES. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 30(1), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13559 (2020).

Weir, C. B. & Jan, A. BMI Classification Percentile And Cut Off Points (StatPearls Publishing, 2023).

Zhang, J., Cao, Y., Mo, H. & Feng, R. The association between different types of physical activity and smoking behavior. BMC Psychiatry 23(1), 927. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05416-1 (2023).

Guo, Z., Li, R. & Lu, S. Leisure-time physical activity and risk of depression: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 101(30), e29917. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000029917 (2022).

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2017-2018/PAQ_J.htm (accessed 14 February 2024).

Elagizi, A., Kachur, S., Carbone, S., Lavie, C. J. & Blair, S. N. A review of obesity, physical activity, and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Obes. Rep. 9(4), 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-020-00403-z (2020).

Kocur, P., Wilski, M., Goliwąs, M., Lewandowski, J. & Łochyński, D. Influence of forward head posture on myotonometric measurements of superficial neck muscle tone, elasticity, and stiffness in asymptomatic individuals with sedentary jobs. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 42(3), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2019.02.005 (2019).

Kremer, M., Becker, L. J., Barrot, M. & Yalcin, I. How to study anxiety and depression in rodent models of chronic pain?. Eur. J. Neurosci. 53(1), 236–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.14686 (2021).

Rosenkranz, S. K., Mailey, E. L., Umansky, E., Rosenkranz, R. R. & Ablah, E. Workplace sedentary behavior and productivity: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(18), 6535. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186535 (2020).

Srinivas, P. et al. Context-sensitive ecological momentary assessment: Application of user-centered design for improving user satisfaction and engagement during self-report. JMIR mHealth uHealth 7(4), e10894. https://doi.org/10.2196/10894 (2019).

Chen, Y. T., Holahan, C. K. & Castelli, D. M. Sedentary behaviors, sleep, and health-related quality of life in middle-aged adults. Am. J. Health Behav. 45(4), 785–797. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.45.4.16 (2021).

Wang, J., Mann, F., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ma, R. & Johnson, S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 18(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5 (2018).

de Rezende, L. F., Rey-López, J. P., Matsudo, V. K. & do Carmo Luiz, O. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes among older adults: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 14, 333. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-333 (2014).

Stults-Kolehmainen, M. A. et al. Measurement of motivation states for physical activity and sedentary behavior: Development and validation of the CRAVE scale. Front. Psychol. 25(12), 568286. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.568286 (2021).

Vaváková, M., Ďuračková, Z. & Trebatická, J. Markers of oxidative stress and neuroprogression in depression disorder. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 898393. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/898393 (2015).

Beurel, E., Toups, M. & Nemeroff, C. B. The bidirectional relationship of depression and inflammation: Double trouble. Neuron 107(2), 234–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.002 (2020).

Miller, A. H. & Raison, C. L. The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16(1), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2015.5.0 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the staff and participants of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–2018 cycle for their valuable contributions. Any interpretation or conclusion related to this manuscript does not represent the views of the CDC or the NHANES. We would also like to thank the editors and reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments to help us improve the manuscript. Ultimately, we would like to extend our special thanks to Professor Guirong Wang for his invaluable guidance.

Funding

This study is supported by the Henan Province Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Program (Grants No.HNGD2022025) and the 2024 Henan Province High-end Foreign Expert Introduction Plan (Grants No.HNGD2024001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M. conceived and designed the study. H.M. and Y.G. organized the database, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. Y.L. contributed to the discussion. H.M., Y.G., K.L., Y.Z., C.W. and Y.L. revised the manuscript. All authors edited, revised, and certified the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Y., Li, K., Zhao, Y. et al. Association between long-term sedentary behavior and depressive symptoms in U.S. adults. Sci Rep 14, 5247 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55898-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55898-6

- Springer Nature Limited