Abstract

Health literacy is an asset for and indicator of adolescents’ health and wellbeing, and should therefore be monitored and addressed across countries. This study aimed to develop and validate a shorter version of the original 10-item health literacy for school-aged children instrument in a cross-national context, using data from the health behaviour in school-aged children 2017/18 survey. The data were obtained from 25 425 adolescents (aged 13 and 15 years) from seven European countries. Determination was made of the best item combination to form a shorter version of the health literacy instrument. Thereafter, the structural validity, reliability, measurement invariance, and criterion validity of the new 5-item instrument were examined. Confirmatory factor analysis showed a good model fit to the data across countries and in the total sample, confirming the structural validity (CFI = 0.995, TLI = 0.989, SRMR = 0.011, RMSEA = 0.031). The internal consistency of the instrument was at a good level across countries (α = 0.87–0.98), indicating that the instrument provided reliable scores. Configural and metric invariance was established across genders, ages, and countries. Scalar invariance was achieved for age and gender groups, but not between countries. This indicated that the factor structure of the scale was similar, but that there were differences between the countries in health literacy levels. Regarding criterion validity, structural equation modelling showed a positive association between health literacy and self-rated health in all the participating countries. The new instrument was found to be valid and reliable for the purposes of measuring health literacy among adolescents in a cross-national context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Different types of skills and knowledge have been identified as central components of wellbeing1. One such component is health literacy. Health literacy is a set of competencies that are required to promote and sustain one’s own health and that of others2,3, bearing in mind the need for people to ‘take control of their health and lead fulfilling lives with a sense of meaning and purpose, in harmony with nature’4. According to WHO5, all adolescents need ‘a broad range of health-related skills and competencies, including skills needed to navigate in virtual environments and digital contexts; the ability to make critical judgments about health and appraise the reliability of health messages across different communication channels; to be able to act in an ethically responsible way in health matters within a diverse and changing world; to become aware of their own needs, perceptions, wishes, and preferences in relation to physical, social and mental health and well-being; and to be able to participate in influencing and carrying out decisions and actions that impact their health, that of others, the environment, and wider society’.

Health literacy is both an asset for and an indicator of health and wellbeing, including among adolescents, and it should therefore be monitored and addressed internationally5. The monitoring of health literacy supports national and regional evidence-informed policy and practice related to the promotion of adolescents’ health and wellbeing.

Among both adults and adolescents, health literacy has been found to explain the variance in health outcomes. Since health literacy competencies can be learned and developed, the disparities in health outcomes caused by health literacy differences can be regarded as avoidable health inequalities, such that disparities in health literacy constitute a health equity issue. Among adolescents, higher health literacy has been linked to many favourable health indicators, including higher levels of physical activity6,7,8,9, self-rated health8,10, better sleeping8, and better eating habits6,8,11. Furthermore, it has been associated with lower levels of smoking8,12,13, alcohol use8,12, health complaints8, problematic social media use10, and obesity13,14. This strand of research has mainly focused on measuring health literacy as a perceived (i.e. subjective) evaluation of one’s competencies. According to the meta-analysis of Sheeran et al.15, perception of one’s own competence is an important factor, requiring attention in interventions to change health behaviour. Furthermore, among adolescents, perceived health literacy has been shown to correlate well with measured health literacy16. A similar link between perceived and measured competencies has been found in several PISA studies, such as those on digital reading17 and mathematics18.

Research on the link between health literacy and health has often focused on selected health indicators, and only rarely on a broad spectrum of indicators. Furthermore, to our knowledge, there has been no longitudinal research on how individual differences in health literacy develop, or on the underlying environmental and individual factors that might explain these differences. To measure health literacy in association with a comprehensive set of health indicators and/or environmental and individual factors, it will be necessary to have health literacy instruments that are brief enough to be integrated within longer surveys or broader study designs. Furthermore, the need to shorten the health literacy instrument has emerged from observations in everyday research. Limitations in the concentration and perseverance of children and adolescents, together with the need to answer a questionnaire that measures several different areas at the same time, can cause fatigue and lack of interest in young respondents, thus reducing the reliability of the survey19.

The monitoring of health literacy across countries calls for theoretically-sound measures that are internationally validated, preferably with the same statistical analyses and sample characteristics20. These premises served as a starting point for developing the health literacy for school-aged children (HLSAC) scale21 in the context of the international health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study. The characteristics of health literacy, as measured by HLSAC, are that it is subjective (involving adolescents’ own evaluation of their competencies), comprehensive, and general (i.e. not focused on one particular health topic). The HLSAC scale contains 10 items that focus on five theory-based components identified as constituting health literacy, as follows: (1) theoretical health information (having knowledge on health-related topics), (2) practical health-related skills (the ability to put theory into practice, e.g. health information-seeking skills, hygiene-related skills), (3) critical thinking skills, (4) self-awareness (i.e. the ability to reflect on issues from one’s personal perspective), and (5) citizenship (i.e. the ability to think of the consequences of one’s actions for the environment, and to promote health in one’s surroundings)3.

Cross-national comparative analysis has shown that the 10-item HLSAC instrument is useful in identifying disparities in health literacy within and between countries22. Furthermore, the instrument has worked well in detecting the link between health literacy and health8,9,11,12. In this context, there has also been discussion on the importance of health literacy as a determinant of health. The discussion has encompassed its power to estimate health outcomes with reference to self-rated health22. According to Idler and Benyamini23, one’s assessment of ‘How in general would you rate your health?’ as an item is ‘a most powerful self-assessment, combining myriad factors from many different domains of life’. In fact, self-rated health has been found to be a robust indicator to predict mortality24 and research has shown an association between better self-rated health and higher health literacy25,26,27,28. Similar findings have been found with the HLSAC instrument when used among adolescents8,22.

The HLSAC scale has been shown to have good potential to measure health-related skills and knowledge in international contexts, and to explain the variance in health outcomes. Though HLSAC is shorter than many other health literacy instruments29, an even shorter version could be useful, bearing in mind the considerable length of many comprehensive health surveys.

Previous research has shown that longer versions of unidimensional measures can be reduced to a third of their original length30. This led us to assume that HLSAC, as a one-factorial measure, could be shortened by half, while bearing in mind the intention of Appel et al.31, ‘to identify a short form with a substantially reduced number of items, which nonetheless exhibits levels of reliability and validity that are comparable to the long form’ (p. 419). In seeking to test the correspondences of the reliability and validity of the original scale with those of the shortened version, the overall test procedures should be the same. In shortening the HLSAC, this means testing the combination of health literacy items that would best predict the original HLSAC instrument, while addressing also the instrument’s structural validity and model fit, its reliability coefficient and internal consistency, and its measurement invariance. In addition, to compare the criterion validity of the scales at different lengths, it is necessary to test whether health literacy, as measured with a shorter version, is linked to other phenomena—including self-rated health22—in the same manner as the longer version20.

There is no gold-standard method for reducing the number of items in a measure. In fact, a variety of approaches may be utilized, combining both theoretical and data-driven methodologies.

Aim of the study

This study aimed to develop and validate a short (5-item) version of the original 10-item HLSAC instrument in a cross-national context (Finland, Estonia, Poland, Czechia, Belgium (Fl.), Slovakia, Germany), using nationally representative data from the HBSC study. In pursuit of this aim, we first determined the best possible combination of items to form a shorter version of the HLSAC scale, taking one item from each of the five theory-based components. We also provided instructions for classification into low, moderate, and high health literacy levels. We then examined the structural validity, reliability, measurement invariance, and criterion validity of the new instrument, here referred to as HLSAC-5.

Results

Construction of the HLSAC-5 instrument

Firstly, regression analyses were conducted to identify the best set of five items for the short health literacy scale. The 10-item score was predicted via a 5-item score consisting of five health literacy items, constrained in such a way as to have at least one item from each core component of health literacy (Table 1). Regression analyses were conducted separately for each country and for all the countries together; this yielded a total of 32 models for each of these conditions.

Table 2 reports the adjusted amount of explained variance (R2) in the country-specific and combined analyses for the 5-item instrument, in terms of predicting the original HLSAC instrument. The results show that while variation in explanatory power exists between countries, it is relatively limited. Although the best combination of health literacy items in the total sample (items HL1, HL3, HL6, HL7, and HL10) did not rank highest in every country when the countries were analysed separately, it still performed very close to the country-specific best combination. The largest difference between the country-specific best item set (explained variance) and the best total sample item set (explained variance) was 0.0153 (Belgium (Fl.)), and the smallest 0.0007 (Slovakia). Taking into account the minimal variability in explanatory power between the total sample and the best country set of items in five countries and the consistent results in two countries, the combination of HL items HL1, HL3, HL6, HL7, and HL10 was regarded as providing the best combination of items to form the short HLSAC-5 instrument (Tables 1 and 2).

When the instruments were compared, the distribution analysis showed that the short HLSAC-5 performed logically, and in the same way as the original HLSAC instrument (Fig. 1). When measured with the short HLSAC-5 instrument, the number of respondents with low health literacy was systematically slightly lower (range 0.3–2.2 percentage points) in all the countries except Slovakia, as compared to the results obtained with the original HLSAC instrument. In addition, when measured by the HLSAC-5 instrument, the number of respondents with moderate health literacy decreased slightly (range 1.8–5.8 percentage points), and the number of respondents with high health literacy increased (range 2.3–7.9 percentage points) in all the countries as compared to the results obtained with the original HLSAC measure. Across the total sample, the differences between the health literacy levels were small (low = 0.6, moderate = 3.0, high = 3.6 percentage points), as measured by the short and the original HLSAC instrument.

Structural validity, item validity, and reliability of the HLSAC-5 instrument

Means, variances, and correlations for the five health literacy items included in HLSAC-5 are presented in Table 3. All the health literacy items were moderately correlated (with correlations varying between 0.36 and 0.48).

CFAs were conducted in order to confirm the structural validity of the HLSAC-5 (consisting of five items selected on the basis of the regression analyses described above). In the CFA, the five items were set to load on one factor. The CFA models were run separately for each country. The results showed that in the total sample and in all the countries, a one-factor model had a good model fit (min. CFI and TLI = 0.979 and 0.958; max. RMSEA and SRMR = 0.047 and 0.020) (Table 4).

In the total sample, standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.59 to 0.72. Finland had the highest factor loadings (λ = 0.79–0.87) and Poland the lowest (λ = 0.48–0.64) (Table 5). The lowest standardized factor loading, 0.48, was in Poland, for item HL1 (‘I have good information about health’). Item-level reliability coefficients (R2) ranged from 0.23 (Poland, Item HL1: ‘I have good information about health’) to 0.76 (Finland, Item HL7: ‘I find health-related information that is easy for me to understand’), suggesting that the latent factor explained 23–76% of the item variances. Cronbach α values for the five items ranged from 0.87 to 0.98, indicating a high internal consistency for the 5-item instrument in all countries.

Measurement invariance of the HLSAC-5 instrument across genders, ages, and countries

The analysis of configural and metric invariance showed that constraining the factor loadings to be equal across countries, age groups, and genders did not substantially decrease the model fit (Country invariance: ΔCFI = 0.001, ΔRMSEA = 0.005; Age invariance: ΔCFI = 0.000, ΔRMSEA = 0.002; Gender invariance: ΔCFI = 0.000, ΔRMSEA = 0.001), indicating that the factor structure was comparable across countries, age groups, and genders (Table 6).

In assessing for scalar invariance, the intercepts of the five items were constrained to be equal across all groups. ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA values showed scalar invariance for age and gender, but not perfectly for country. These results indicated that for both age groups and both genders, the factor structure and item levels did not differ. However, there were differences between countries, indicating that while the factor structure was similar, there were health literacy level differences between the countries (Table 6).

Criterion validity

In the total/pooled sample, there was a positive association between health literacy and self-rated health, indicating that higher health literacy was associated with higher self-rated health. In line with the pooled sample, the analysis by country showed a positive association between health literacy and self-rated health in all seven participating countries, with regression coefficients ranging from β = 0.15 in Germany to β = 0.32 in Belgium (Fl.). Health literacy explained self-rated health to some extent, ranging from 2% in Germany to 10% in Belgium (Fl.) and Finland (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The aim was to construct and validate a brief, theoretically comprehensive, and internationally comparable instrument for measuring children’s and adolescents' subjective health literacy. The cross-national development and validation process encompassed seven European countries and was based on the original 10-item HLSAC instrument21. The original HLSAC instrument has been validated in several studies9,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 and has proven to be an appropriate tool for measuring subjective health literacy. However, for large-scale studies where the purpose is to explore the relationship between health literacy and other phenomena, there is a need for shorter instruments.

The research resulted in a 5-item HLSAC-5 instrument containing one item from each of the health literacy theoretical core components. For the total sample, the HLSAC-5 instrument had good predictive properties, predicting 90% of the variance of the original 10-item HLSAC instrument. The HLSAC-5 was constructed as a one-factor model, similar to the original longer HLSAC instrument. All five items were derived from a conceptual framework; they contribute substantially to the underlying construct of health literacy, addressing the recommended attributes for such a measure42,43. The essential advantage of the one-factor model is that it does not violate the requirement on additivity, and enables reliable calculation and interpretation of sum scores. It thus differs from multifactorial health literacy scales, which consist of several subscales44,45. Although the HLSAC-5 instrument is based on five theoretical core components, it is possible to construct a one-factor model, because background theory and previous studies have shown that the core components are partly overlapping (having cross-correlations) and exist in a somewhat hierarchical relationship with each other3,21.

The challenge in constructing a short, comprehensive, and generic health literacy instrument lies in the need to adequately take into account the complex and multidimensional nature of health literacy. Interpretative clarity of the model is essential, meaning that one must go beyond modifying every detail in pursuit of statistical adequacy (thus seeking a balance between content validity and structural validity). As there was only a small difference in explanatory power between the country-specific models and the total sample model, the items selected for the final model can be considered to form a sound and content-valid measure of health literacy, regardless of the country in question.

There was some variation between countries regarding the items measuring theoretical knowledge, critical thinking, and citizenship. The items finally selected for the model were ‘I have good information about health’, ‘I can compare health-related information from different sources’ and ‘I can judge how my own actions affect the surrounding natural environment’. Note that regarding the items that were not selected for the model, the respondents had to assess their ability to give examples on how to promote health (theoretical knowledge), decide whether health information is right or wrong (critical thinking), and give ideas on how to promote health in the person's immediate surroundings, such as the nearby place or family (citizenship). These items were selected for the country-specific model in some countries, but not in others. One reason for this may be that young people from different countries may perceive their skills in the tasks required to produce differently. Items measuring practical knowledge and self-awareness (‘When necessary, I find health-related information that is easy for me to understand’ and ‘I can judge how my own actions affect the surrounding natural environment’) were found appropriate for the model in almost every country surveyed. These items may require less interpretation and be slightly less cognitively challenging than their alternative items, and they could therefore be selected for the model in a relatively unequivocal way.

For descriptive purposes, the health literacy levels were classified into three groups (low, moderate, high) based on cut-off scores. Inspection of the response distributions showed that the short HLSAC-5 instrument performed logically in the classification of health literacy levels, i.e. in the same way as the original HLSAC instrument. However, there were small differences between the two scales; thus, when HLSAC-5 was used the proportion of respondents with low and moderate health literacy was slightly smaller, and the proportion of respondents with high health literacy somewhat greater. This may be because the selected smaller number of items approached health literacy in a more limited way, thus placing greater emphasis on the single competency as expressed in a single item.

Examination of the structural validity provides evidence on the construct validity of the instrument46,47. The structural validity of the HLSAC-5 was analysed via CFA, i.e. with the model-fit parameters indicating how the data fitted into the assumed factor structure. This kind of structural validation is a strong method to examine the validity of an instrument when (as was the case in this study) the instrument structure is specified a priori, and when the contextualization is based on evidence from previous research47. The HLSAC-5 instrument’s overall goodness and sufficiency were at a good level, and the instrument showed an excellent fit with the data in all the participating countries. This was a notable result, especially considering the large amount of data involved39,48,49.

The reliability of HLSAC-5 was inspected. Both item reliability and scale reliability were at an adequate level. The factor loadings and reliability coefficients (R2) indicated that the items were reliable measures of a latent variable (health literacy). The internal consistency reliability varied to some extent between countries, but was at a high level in the total sample, exhibiting a Cronbach alpha of 0.80. This means that the items measured the same construct. The high α-value is also noteworthy, bearing in mind that the number of items included in the instrument has an impact on the value of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, with a low number of items reducing the α-value50. Despite this, the HLSAC-5 instrument with five items demonstrated a high level of internal consistency.

Regarding measurement invariance, configural and metric invariance was established across genders, ages, and countries. Scalar invariance was achieved for age and gender groups, but not between countries. This indicated that the structure of the instrument was similar across countries and that it properly measured the same phenomenon in each country, but that there were differences in the levels of health literacy between countries. The establishment of configural, metric, and partial scalar invariance, together with the excellent fit of the model to the data, indicates that partial invariance holds, and provides a sufficient condition for comparing mean values between countries51,52. This can be regarded as a good result, considering the number of countries involved and the size of the sample. One should note the well-known difficulty of achieving full measurement invariance in most empirical studies53,54,55; in particular, scalar invariance has been described as an unachievable ideal that can only be approximated in practice53. There can be several reasons why full measurement invariance is not often met in large cross-national studies such as the present study. The original HLSAC instrument, which was used as a starting point for the study, was in the English language, with subsequent translation into the language of the target countries (translation–back translation). Even if the translation process was carried out to a high standard, minor differences of interpretation may remain, and together with possible cultural differences, the meanings of the response options or the items may involve slightly different connotations. There may also be other explanations: for example, participants' understanding of the content of the items can vary, as may familiarity of the participants with the response format, or the extent to which respondents give socially acceptable answers56,57.

There is no gold standard scale for measuring children’s and adolescents’ health literacy, and hence no absolute criterion for assessing the validity of the HLSAC-5 instrument. Here, criterion validity was assessed in relation to self-rated health, in line with the notion of defining ‘the extent to which a construct [here, health literacy] relates to another construct that it should theoretically be related to’20. As measured with the HLSAC-5 instrument, health literacy was associated with differences in self-rated health in each participant country. On average, the short instrument explained 7% of the variance in self-rated health, which is similar to the results on the original 10-item HLSAC instrument22. Paakkari et al.22 discuss what coefficient of determination would be sufficient to indicate an important or critical factor for self-rated health. In line with DeSalvo et al.24, they emphasize that self-rated health is a robust predictor of mortality, and argue that ‘any factor that contributes to a decrease in health disparities is important, including health literacy’. It should also be noted that according to previous studies, health literacy explains more of adolescents’ self-rated health than, for example, family affluence, gender, age, school achievement, or educational orientation8,22, which are often considered to be valid explanatory factors.

This study was based on a previously-developed HLSAC instrument. This limited the choice of items and precluded the possibility of developing a completely new health literacy instrument. It should also be noted that the conceptual framework behind the HLSAC-5 tool is only one possible way to conceptualize health literacy. In using the instrument, it will be important to know the framework that it is based on, the purposes and contexts appropriate to its use, and the advantages or limitations thus implied. Even a good health literacy instrument can give biased results if used in the wrong context. The HLSAC-5 instrument is by nature a comprehensive and generic tool, based on a relatively broad notion of health literacy. It can provide a good overview of health literacy, but domain-specific instruments may be capable of providing a more focused picture of health literacy in a specific context. Note also that the current HLSAC-5 instrument has been validated for 13- and 15-year-olds; hence, further research is needed on the applicability of the instrument to both younger and older age groups.

Health literacy has been shown to be a relevant indicator of and contributor to adolescents’ health and wellbeing, highlighting the need to research health literacy across countries, and to develop appropriate measurement tools for this purpose. The present study indicated that HLSAC-5 is a valid and reliable instrument for use in a cross-national context. Its brevity also makes it applicable as a component of large-scale surveys in which a range of phenomena are examined at the same time.

Methods

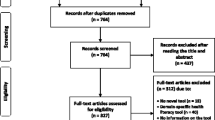

Study design and participants

Data from the HBSC study were used. The HBSC study is an international World Health Organization collaborative cross-sectional study. It is conducted every four years in a growing network of countries and regions within the World Health Organization European Zone, and in North America58,59. Following the common international HBSC research protocol, nationally representative data sets were ensured using random cluster sampling with the school as the primary sampling unit60,61. Within each school, one class was randomly selected. All countries in the HBSC study comply with the required ethical and data-gathering standards. Students answered the questionnaire voluntarily and anonymously during school hours via an electronic or paper–pencil survey60.

For the present study, a population-based cross-sectional design was used. The study covered those countries that included the measure of health literacy for both 13- and 15-year-olds in the 2017/2018 survey. The total sample consisted of 25,425 adolescents from seven countries (Table 7).

Ethical approval and consent for participation

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and it obtained ethical approval from the University of Jyväskylä Ethical Committee. The school principals gave school-level approval. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study as well as from their parents/guardians.

Measures

Health literacy

The HLSAC instrument21 was used to measure the adolescents’ subjective (self-reported, perceived) health literacy. The validated 10-item instrument contains two items from each of five previously-identified core components, namely theoretical knowledge, practical knowledge, critical thinking, self-awareness, citizenship3. Respondents evaluated the 10 items starting with ‘I am confident that…’ on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all true, 2 = not completely true, 3 = somewhat true, 4 = absolutely true).

Self-rated health

Self-rated health was evaluated by a single question measuring the individual’s evaluation of their health and having four response options (1 = excellent, 2 = good, 3 = fair, 4 = poor)62. For the purposes of CFA the scale was reversed to have higher values indicating higher self-rated health (reversed values: 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = excellent).

Demographic characteristics

Gender (1 = girl, 2 = boy) was self-reported. Age was computed based on the respondent’s month and year of birth, and the date of the survey assessment. According to the HBSC protocol, respondents are assigned to three age categories, i.e. as being of ages 11 (≥ 10.5 and ≤ 12.5), 13 (> 12.5 and ≤ 14.5), and 15 (> 14.5 and ≤ 15.5). The age categories 13 and 15 years were used in this study.

Data analysis

First of all, regression analysis was used to determine the combination of five health literacy items that best predicted the original HLSAC instrument (consisting of 10 items). In the regression analyses, all the different sets of five items were tested for their predictive ability with regard to the original HLSAC. In line with the theoretical basis of the HLSAC21, all the 5-item sets were constructed in such a way as to contain one item from each theoretical core component included in the original HLSAC instrument. The rationale for choosing regression analysis as a tool to determine the items for the new HLSAC-5 measure was, in part, because we wanted to stay true to the original scale as far as reasonably possible, and hence achieve an explanatory power as close as possible to that of the original scale. We further theorized that closeness to the original scale would yield similar characteristics and associations to other variables (notably self-rated health) as the original HLSAC. Regression analysis was deemed a suitable tool, since it would allow us to use theoretical reasoning in choosing the restrictions that had to be in place for the items in the new HLSAC-5 measure.

Only 32 models met the condition that there should be one item from each of the five core components. In total, 32 regression models were fitted for each country in the dataset, as were 32 models for all the countries together. In all the fitted models the original 10-item HLSAC instrument was considered to be the response variable, and the candidate short HLSAC instrument the predictor. The fitted models were ranked by their adjusted R2 values, and the model with the highest coefficient of determination was regarded as comprising the best 5-item HLSAC instrument in terms of predicting the original HLSAC instrument.

To classify the responses into low, moderate, and high health literacy levels, sum scores were used. In the 10-item HLSAC measure, the classifications were built in the following manner: low (score 10–26), moderate (score 27–35), and high (score 36–40)63. For the 5-item HLSAC-5 measure, the thresholds for the levels were set by adopting a similar line of reasoning as for the longer measure: low (score 5–12), moderate (score 13–17), and high (score 18–20).

Structural validity was used to assess the extent to which the five selected items reflected the underlying dimension, i.e. health literacy. The structural validity was examined by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In the one-factor model, standardized factor loadings indicate direct structural relations between the latent factor and the item64. The CFA model fit was evaluated using the χ2-test and the following fit-indices: Tucker Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and RMSEA34. For TLI and CFI, values equal to or above 0.95 represent a good fit48. The RMSEA and SRMR values should be less than 0.06 and 0.08, respectively48.

The reliability of the five items was estimated by reliability coefficients (R2), and the internal consistency of the scale by Cronbach’s α. An alpha higher than 0.70 is regarded as indicating good internal consistency65.

Measurement invariance across gender, age, and country was determined through a multi-group analysis. We tested whether the underlying factor structure was consistent, regardless of whether the scale was used with girls or boys, with 13- or 15-year-olds, or with different countries. The models were first estimated for subgroups independently. The equivalence of the factor structure parameters was then tested in a hierarchical order (for configural, metric, and scalar invariance) as suggested by Byrne66. Configural invariance, with no restrictions, was first estimated. The metric invariance was tested by constraining the factor loadings to be equal across groups. Scalar invariance was examined by constraining the item intercepts to be equal across groups. Measurement invariance was established when the restrictions decreased CFI by not more than 0.010 and increased RMSEA by not more than 0.015, relative to the prior model67,68.

Criterion validity refers to the extent to which a construct relates to another construct that it should theoretically be related to Ref.20. As better self-rated health has been found to be moderately associated with higher health literacy in numerous studies8,22,25,26,27,28, a positive association between these two factors was used as an indicator of appropriate criterion validity. In this study, structural equation modelling was used to analyse the association between health literacy and self-rated health; this was done by combining CFA and regression analysis within the same model.

All the analyses were conducted with the Mplus 7.0 statistical package69, except for regression analyses predicting the original HLSAC instrument with the proposed HLSAC-5 instruments, which were performed with the statistical analysis software R70. The CFA parameters were estimated using the maximum likelihood robust estimation method (MLR). Cases with missing values were included in the analyses and treated with the missing-at-random data procedure in Mplus.

Data availability

The data were provided by the HBSC Data Management Centre at the University of Bergen, Norway, to which requests for data should be submitted (dmc@hbsc.org).

References

The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. http://www.oecd.org/education/2030/oecd-education-2030-position-paper.pdf (2018).

Nutbeam, D. & Muscat, D. M. Health promotion glossary 2021. Health Promot. 36, 1578–1598. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa157 (2021).

Paakkari, L. & Paakkari, O. Health literacy as a learning outcome in schools. Health Educ. 112, 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/09654281211203411 (2012).

World Health Organization. Geneva Charter for Well-Being. Series of Technical Papers. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/health-promotion/geneva-charter-4-march-2022.pdf?sfvrsn=f55dec7_21&download=true (World Health Organization, 2021).

World Health Organization. Health Literacy in the Context of Health, Well-Being and Learning Outcomes the Case of Children and Adolescents in Schools: The Case of Children and Adolescents in Schools. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344901 (Regional Office for Europe, 2021).

Korkmaz Aslan, G., Kartal, A., Turan, T., Taşdemir Yiğitoğlu, G. & Kocakabak, C. Association of electronic health literacy with health-promoting behaviours in adolescents. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 27, e12921. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12921 (2021).

Levin-Zamir, D., Lemish, D. & Gofin, R. Media Health Literacy (MHL): Development and measurement of the concept among adolescents. Health Educ. Res. 26, 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyr007 (2011).

Paakkari, L. et al. Does health literacy explain the link between structural stratifiers and adolescent health?. Eur. J. Public Health 29, 919–924. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz011 (2019).

Sukys, S., Tilindiene, I. & Trinkuniene, L. Association between health literacy and leisure time physical activity among Lithuanian adolescents. Health Soc. Care Community 29, e387–e395. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13363 (2021).

Paakkari, L., Tynjälä, J., Lahti, H., Ojala, K. & Lyyra, N. Problematic social media use and health among adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041885 (2021).

Ayaz-Alkaya, S. & Kulakçı-Altıntaş, H. Nutrition-exercise behaviors, health literacy level, and related factors in adolescents in Turkey. J. Sch. Health 91, 625–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.13057 (2021).

Kinnunen, J. et al. The role of health literacy in the association between academic performance and substance use. Eur. J. Public Health 32, 182–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckab213 (2022).

Sansom-Daly, U. M. et al. Health literacy in adolescents and young adults: An updated review. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 5, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2015.0059 (2016).

Shih, S. F., Liu, C. H., Liao, L. L. & Osborne, R. H. Health literacy and the determinants of obesity: A population-based survey of sixth grade school children in Taiwan. BMC Public Health 16, 280. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2879-2 (2016).

Sheeran, P. et al. Does increasing autonomous motivation or perceived competence lead to health behavior change? A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 40, 706–716. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001111 (2021).

Summanen, A.-M. Terveystiedon oppimistulokset perusopetuksen päättövaiheessa 2013. [The Health Education Learning Outcomes at the End of Basic Education in 2013] (Juvenes Print, Berlin, 2014).

Yu, R., Wang, M. & Hu, J. The relationship between ICT perceived competence and adolescents’ digital reading performance: A multilevel mediation study. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 61, 817–846 (2023).

Hiltunen, J. & Nissinen, K. Erinomaiset matematiikan osaajat. [Excellent mathematicians]. In PISA—pintaa syvemmältä. PISA 2015 Suomen pääraportti. [PISA 2015 Finland main report] (eds Rautopuro, J. & Juuti, K.) 213–234 (Jyväskylän yliopistopaino, 2018). https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/59526/978-952-5401-82-0_PISA.pdf.

Aarø, L. E. et al. Nordic adolescents responding to demanding survey scales in boring contexts: Examining straightlining. J. Adolesc. 94, 829–843. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12066 (2022).

Boer, M. et al. Cross-national validation of the social media disorder scale: Findings from adolescents from 44 countries. Addiction 117, 784–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15709 (2022).

Paakkari, O., Torppa, M., Kannas, L. & Paakkari, L. Subjective health literacy: Development of a brief instrument for school-aged children. Scand. J. Public Health 44, 751–757. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816669639 (2016).

Paakkari, L. et al. A comparative study on adolescents’ health literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 3543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103543 (2020).

Idler, E. L. & Benyamini, Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 38, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/2955359 (1997).

DeSalvo, K. B., Bloser, N., Reynolds, K., He, J. & Muntner, P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 21, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x (2006).

Eronen, J., Paakkari, L., Portegijs, E., Saajanaho, M. & Rantanen, T. Assessment of health literacy among older Finns. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 31, 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-018-1104-9 (2019).

Furuya, Y., Kondo, N., Yamagata, Z. & Hashimoto, H. Health literacy, socioeconomic status and self-rated health in Japan. Health Promot. Int. 30, 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat071 (2015).

Levin-Zamir, D., Baron-Epel, O. B., Cohen, V. & Elhayany, A. The association of health literacy with health behavior, socioeconomic indicators, and self-assessed health from a national adult survey in Israel. J. Health Commun. 21, 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1207115 (2016).

Nie, X., Li, Y., Li, C., Wu, J. & Li, L. The association between health literacy and self-rated health among residents of china aged 15–69 years. Am. J. Prev. Med. 60, 569–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.032 (2021).

Guo, S. et al. Quality of health literacy instruments used in children and adolescents: A systematic review. BMJ Open 8, e020080. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020080 (2018).

Lins de Holanda Coelho, G., Hanel, P. & Wolf, L. The very efficient assessment of need for cognition: Developing a six-item version. Assessment 27, 1870–1885. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191118793208 (2020).

Appel, M., Gnambs, T. & Maio, G. R. A short measure of the need for affect. JPA 94, 418–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2012.666921 (2012).

Boberová, Z., Ropovik, I., Kolarčik, P., Gecková, A. M. & Paakkari, L. Štruktúra zdravotnej gramotnosti u adolescentov [The structure of health literacy in adolescents]. Cesk. Psychol. 63, 1–12 (2019).

Bonde, A. H. et al. Translation and validation of a brief health literacy instrument for school-age children in a Danish context. HLRP 6, e26–e29. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20220106-01 (2022).

Fischer, S. et al. Measuring health literacy in childhood and adolescence with the scale Health Literacy in school-aged children—German version. The psychometric properties of the German-language version of the WHO health survey scale HLSAC. Diagnostica 68, 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000296 (2022).

Haney, M. O. Psychometric testing of the Turkish version of the health literacy for school-aged children scale. J. Child Health Care 22, 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493517738124 (2018).

Masson, J., Darlington-Bernard, A., Vieux-Poule, S. & Darlington, E. Validation française de l’échelle de littératie en santé des élèves HLSAC (Health literacy for school-aged children). [French validation of the Health literacy for school-aged children (HLSAC)]. Santé Publ. 33, 705–712. https://doi.org/10.3917/spub.215.0705 (2021).

Mazur, J., Małkowska-Szkutnik, A., Paakkari, L., Paakkari, O. & Zawadzka, D. The Polish version of the short scale measuring health literacy in adolescence. Dev. Period Med. 23, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.34763/devperiodmed.20192303.190197 (2019).

Paakkari, O. et al. The cross-national measurement invariance of the health literacy for school-aged children (HLSAC) instrument. Eur. J. Public Health 29, 432–436. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky229 (2019).

Riiser, K., Helseth, S., Haraldstad, K., Torbjørnsen, A. & Richardsen, K. R. Adolescents’ health literacy, health protective measures, and health-related quality of life during the Covid-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 15, e0238161. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238161 (2020).

Rouquette, A. et al. Health literacy throughout adolescence: Invariance and validity study of three measurement scales in the general population. Pat. Educ. Couns. 105, 996–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.07.044 (2022).

Velasco, V., Gragnano, A., Gruppo Regionale Hbsc Lombardia & Vecchio, L. P. Health literacy levels among Italian students: Monitoring and promotion at school. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 9943. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199943 (2021).

Jordan, J. E., Osborne, R. H. & Buchbinder, R. Critical appraisal of health literacy indices revealed variable underlying constructs, narrow content and psychometric weaknesses. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64, 366–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.005 (2011).

Pleasant, A., McKinney, J. & Rikard, R. V. Health literacy measurement: A proposed research agenda. J. Health Commun. 16, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.604392 (2011).

Altin, S. V., Finke, I., Kautz-Freimut, S. & Stock, S. The evolution of health literacy assessment tools: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 14, 1207 (2014).

Finbråten, H. S. et al. Validating the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire in people with type 2 diabetes: Latent trait analyses applying multidimensional Rasch modelling and confirmatory factor analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 73, 2730–2744 (2017).

Mokkink, L. B. et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63, 737–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006 (2010).

de Vet, H. C. W., Terwee, C. B., Mokkink, L. B. & Knol, D. L. Measurement in Medicine. Practical Guides to Biostatistics and Epidemiology (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999).

Bentler, P. M. & Bonett, D. G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 88, 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588 (1980).

Sijtsma, K. On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika 74, 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0 (2009).

Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J. & Muthen, B. Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychol. Bull. 105, 456–466 (1989).

Steenkamp, J. B. & Baumgartner, H. Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 25, 78–90 (1998).

Marsh, H. W. et al. What to do when scalar invariance fails: The extended alignment method for multi-group factor analysis comparison of latent means across many groups. Psychol. Methods 23, 524–545. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000113 (2018).

Davidov, E., Muthen, B. & Schmidt, P. Measurement invariance in cross-national studies: Challenging traditional approaches and evaluating new ones. Sociol. Methods Res. 47, 631–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118789708 (2018).

Van De Schoot, R., Schmidt, P., De Beuckelaer, A., Lek, K. & Zondervan-Zwijnenburg, M. Editorial: Measurement invariance. Front. Psychol. 6, 1064. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01064 (2015).

Davidov, E., Meuleman, B., Cieciuch, J., Schmidt, P. & Billiet, J. Measurement equivalence in cross-national research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 40, 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043137 (2014).

Oberski, D. L., Weber, W. & Revilla, M. The effect of individual characteristics on reports of socially desirable attitudes towards immigration. In Methods, Theories, and Empirical Applications in the Social Sciences: Festschrift for Peter Schmidt (eds Salzborn, S. et al.) 151–158 (Springer, 2012).

Currie, C., Nic Gabhainn, S., Godeau, E., International HBSC Network Coordinating Committee. The health behaviour in school-aged children: WHO Collaborative Cross-National (HBSC) study: Origins, concept, history and development 1982–2008. Int. J. Public Health 54, 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-5404-x (2009).

Inchley, J. et al. (Eds). Spotlight on Adolescent Health and Well-Being. Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada. International report. Volume 1. Key findings. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332091/9789289055000-eng.pdf (2020).

Inchley, J., Currie, D., Cosma, A. & Samdal, O. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study Protocol: Background, Methodology and Mandatory Items for the 2017/18 Survey (CAHRU, 2018).

Schnohr, C. W. et al. Trend analyses in the health behaviour in school-aged children study: Methodological considerations and recommendations. Eur. J. Public Health 25, 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv010 (2015).

Kaplan, G. A. & Camacho, T. Perceived health and mortality: A nine-year follow-up of the human population laboratory cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 117, 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113541 (1983).

Paakkari, O., Torppa, M., Villberg, J., Kannas, L. & Paakkari, L. Subjective health literacy among school-aged children. Health Educ. 118, 182–195. https://doi.org/10.1108/HE-02-2017-0014 (2018).

Bollen, K. A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables (Wiley, 1989).

Nunnally, J. C. Psychometric Theory 2nd edn. (McGraw-Hill, 1978).

Byrne, B. M. Testing for multigroup equivalence of a measuring instrument: A walk through the process. Psicothema 20, 872–882 (2008).

Cheung, G. W. & Rensvold, R. B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 9, 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 (2002).

Chen, F. F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 14, 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834 (2007).

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables 7th edn. (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012).

R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design as well as interpretation of the data and analysis. Data preparation and analysis were conducted by M.K., N.L. and M.T. The first draft of the manuscript were written by O.P., L.P., M.K. and N.L. All authors commented on and edited the first version of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paakkari, O., Kulmala, M., Lyyra, N. et al. The development and cross-national validation of the short health literacy for school-aged children (HLSAC-5) instrument. Sci Rep 13, 18769 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45606-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45606-1

- Springer Nature Limited