Abstract

We used next-generation sequencing to evaluate the quantity and genetic diversity of the HIV envelope gene in various compartments in eight patients with acute infection. Plasma (PL) and seminal fluid (SF) were available for all patients, whole blood (WB) for seven, non-spermatozoid cells (NSC) for four, and saliva (SAL) for three. Median HIV-1 RNA was 6.2 log10 copies/mL [IQR: 5.5–6.95] in PL, 4.9 log10 copies/mL [IQR: 4.25–5.29] in SF, and 4.9 log10 copies/mL [IQR: 4.46–5.09] in SAL. Median HIV-1 DNA was 4.1 log10 copies/106 PBMCs [IQR: 3.15–4.15] in WB and 2.6 log10 copies /106 Cells [IQR: 2.23–2.75] in NSC. The median overall diversity per patient varied from 0.0005 to 0.0232, suggesting very low diversity, confirmed by the clonal aspect of most of the phylogenetic trees. One single haplotype was present in all compartments for five patients in the earliest stage of infection. Evidence of higher diversity was established for two patients in PL and WB, suggesting compartmentalization. Our study shows low diversity of the env gene in the first stages of infection followed by the rapid establishment of cellular reservoirs of the virus. Such clonality could be exploited in the search for early patient-specific therapeutic solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding the dynamics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transmission is important in the design of effective prevention and treatment strategies. Several studies suggest that early stages of HIV infection may disproportionately contribute to viral transmission and spread of the epidemic1. Indeed, recent infection, particularly primary HIV infection (PHI), is associated with a high viral burden in blood and semen, a major determinant of HIV transmission2,3,4,5. Within the first weeks of infection, HIV rapidly disseminates throughout the body and establishes cellular HIV reservoirs and compartments6. Phylogenetic analyses of founder viruses in various epidemic settings support the notion of a genetic bottleneck, with only a single founder in almost all cases of sexual transmission7,8. Such a genetic bottleneck leads to low genetic diversity and clonal representation of the viral population in patients with a PHI. Several biological factors have been suggested to be responsible, including the mucosa in the sexual tract9, the availability of target cells10, and the levels of immune activation and genital inflammation11.

Viral compartmentalization within anatomical regions has been documented in PHI, mainly in the central nervous system and genital tract6. This is a consequence of restricted viral migration between anatomical sites or tissues12. Such compartmentalization affects HIV-associated pathogenesis and is involved in neurocognitive disease13 and sexual transmission14,15,16. For example, the male genital tract represents an unique compartment, with differences in viral replication and specific evolution in response to local environmental factors17,18,19.

Here, we used ultra-deep sequencing (UDS) to determine the quantity and genetic diversity of the HIV envelope gene to assess the diversity of the virus and characterize the dynamics of viral spread between several compartments (plasma, whole blood, seminal fluid, non-spermatozoid cells, and saliva) in patients with a primary infection.

Results

Patient characteristics

Eight patients (P1 to P8) were enrolled in this study at the time of PHI. The clinical characteristics of each are described in Table 1. All were men with a median age of 37.5 years (seven reporting sex with men and one reporting heterosexual behavior). Primary infection was symptomatic in four cases. Median CD4 cell counts and HIV-1 RNA levels were 523 cells/mm3 (range: 103–707) and 6.2 log10 copies/mL [range: 5.5–6.95], respectively. One patient was classified as Fiebig II, two as Fiebig IV, and five as Fiebig V. Four patients have a negative HIV serological test in the last 3 months before the study. Using tool for HIV estimation date20, 7 out of the 8 patients, had an estimated date of infection lower than 30 days. Six patients were infected with a subtype B virus and two with CRF02_AG. Viral tropism was CCR5 in seven cases and CCR5/CXCR4 in one.

Quantification of HIV-1 RNA and DNA

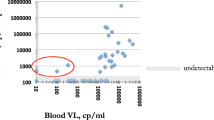

Plasma (PL) and seminal fluid (SF) were available for all eight patients, whole blood (WB) for seven, non-spermatozoid cells (NSC) for four, and saliva (SAL) for three. The median HIV-1 RNA level was 6.2 log10 copies/mL [IQR 5.5–6.95] in PL, 4.9 log10 copies/mL [4.25–5.29] in SF, and 4.9 log10 copies/mL [IQR 4.46–5.09] in SAL. The median HIV-1 DNA level was 4.1 log10 copies/106 PBMC [IQR 3.15–4.15] in WB and 2.6 log10 copies /106 cells [IQR 2.23–2.75] in NSC. During PHI, PL HIV RNA levels were higher than those in all other compartments for seven patients, whereas the viral load (VL) in SAL was slightly higher than that in PL (4.88 log10 vs 4.59 log10) for the remaining patient (P6) (Fig. 1).

HIV viral loads in five compartments of patients with primary infection. HIV RNA was estimated in plasma (PL), saliva (SAL), and seminal fluid (SF) expressed in log10 copies/ml. HIV DNA was quantified in PBMCs (WB) and non-spermatozoid cells (NSC) and expressed in log10 copies/106 PBMCs or cells, respectively. P: patient.

Diversity of the env gene

We sequenced the C2V3 region between positions 7008–7385 bp of the HXB2 reference sequence using UDS. Amplification was performed for the eight SF samples and seven PL, six WB, three SAL, and two NSC samples. After read filtration based on quality parameters, we estimated a median of 5,792 representative sequences for each sample, with an average length of 200 bp and a deep average of 5,562 reads by position. The overall mean distance i.e. the mean pairwise genetic Tamura Nei21 distance between reads in each compartment is represented in Fig. 2.

Average diversity of HIV sequences in compartments from patients with a primary infection according to Fiebig stage. The estimated overall mean distance of the reads is represented for each of the compartments. NSC: non-spermatozoid cells, PL: plasma, SAL: saliva, SF: seminal fluid, WB: whole blood.

Diversity estimates were very low, from 0.0005 to 0.0232. For most of the analyzed samples, the diversity was 0.005, with some exceptions, such as PL and WB for P5 and P7, SAL for P5, and SF for P6 and P7.

Figure 2 shows a tendency to increase the dispersion of mean diversity estimates among Fiebig stage V patients. To assess whether there is a differential pressure between the compartments in Fiebig stage IV and V patients, we evaluated the relationship between diversity and compartment and Fiebig stage with a generalized linear mixed models. These models didn’t find a significant association between the compartment and/or Fiebig stage with the diversity (Supplementary Note S1). The lack of effect of the compartments on the diversity of Fiebig stage IV and V patients can be observed in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Haplotype and phylogenetic analysis

Haplotype analysis was performed for seven of the eight patients, as we could not recover viral haplotypes from P1 due to low sequence coverage (Supplementary table 1). The patients could be divided into two groups based on the number and diversity of the haplotypes. In the first (P2, P3, P4, P6, P8), each compartment of the same patient showed one or two haplotypes, with high sequence similarity (intra-patient). Phylogenetic trees confirmed low diversity for P2, P3, P4, P6, and P8, with a clonal aspect and the characteristic star-like phylogeny (Supplementary Figure 2). The second group of patients, consisting of P5 and P7, showed greater diversity, with 16 and 13 haplotypes, respectively. The compartment with the highest number of haplotypes in P7 was the PL (n = 7), whereas WB was the most diverse compartment for P5 (n = 10). The phylogenetic tree for P5 showed high diversity and a specific pattern of nucleotide variation, suggesting potential compartmentalization. Similarly, we found distinct compartment-specific clusters of variants in the blood and plasma of P7 (Fig. 3).

Phylogenetic trees of the HIV haplotypes identified in Patients 5 and 7. The size of the circumference in the phylogenetic trees is proportional to the frequency of the haplotype in the respective compartment and is indicated for each branch. The nucleotide substitutions identified by the Highlighter tool (www.hiv.lanl.gov) are represented at the front of each haplotype.

Evidence of compartmentalization in later Fiebig stages

The results of the Fst and Slatkin-Maddison tests are presented in Table 2. We found no evidence of compartmentalization among the various compartments of P2, P3, P6, or P8. P4 showed NSC compartmentalization relative to the other compartments (WB, PL, SF), P5 compartmentalization among all compartments sampled (PL, WB, SAL, SF), and P7 significant divergence between the WB-PL and PL-SF pairs.

Role of positive selection in the compartmentalization of patients with primary infection

We evaluated the evidence of positive selection in the HIV haplotypes for each patient. Only P5 and P7 showed evidence of positive selection in the PL and WB compartments. Many of the amino-acid changes in the HIV haplotypes of P5 (10/13, 77%) and P7 (6/11, 55%) were under positive selection (Supplementary Fig. S3).

We performed a factorial correspondence analysis to establish whether these amino-acid changes under positive selection were a sign of a potential compartmentalization process. These substitutions were unable to discriminate the haplotypes depending on the compartment for P5. Conversely, the mutations under positive selection separated the haplotypes of the PL from WB compartment for P7. The three mutations with the strongest discriminant power for P7 were G358W, K359Q, and D268N. We investigated whether any mutations under positive selection could be a potential glycosylation site and identified only the D7N mutation (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Discussion

At the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the quantity and genetic diversity of HIV in different compartments (blood, genital compartment, and saliva) in patients with a primary infection. HIV-RNA levels were high in semen (median 4.9 log10 copies/ml), albeit lower than in PL, consistent with the results of previous studies in PHI. The burden of the presence of HIV particles in semen can be particularly critical for the risk of transmission, especially in MSM2,22,23,24. We also found a high level of HIV RNA in SAL for the three patients with available samples. In a recent study, Ikeno et al. reported that the salivary viral load is approximately 10% of the PL viral load but that it can be even higher than the PL viral load in some patients25. In contrast to SF, SAL has been shown to lyse HIV particles in vitro due to hypotonicity and many salivary proteins inhibit and inactivate HIV particles26. The high and similar amounts of HIV RNA in the cell-free compartments suggest the passive diffusion of HIV from PL to the SF and SAL. The median level of HIV DNA in WB was 4.1 log10 copies/106 PBMCs, suggesting the very early establishment of a cell reservoir, as previously described2. Conversely, we found low levels of HIV DNA in NSC, suggesting that the semen reservoir is established later than the blood reservoir during PHI.

Overall, we found little diversity in the HIV-1 quasispecies populations in compartments in eight men with acute infection. Our findings are compatible with a very early HIV-1 transmission bottleneck. The absence of structure of the phylogenetic trees and the small number of haplotypes favor single transmission for most patients. The percentage of sexual transmission events involving a single variety of HIV has been estimated to be from 76% to 80%7,9. Whether the percentage of patients with multiple variants could be greater among MSM patients is a subject of debate27. Our results do not support the multiple-transmission hypothesis, although we cannot exclude the possibility that the subjects were exposed to a relatively homogeneous viral population (if the transmitting partners had acute infections themselves).

The homogeneity of viral haplotypes suggests effective dispersion of the founder haplotype or a single haplotype derived early after transmission. The homology of the SF and PL haplotypes is evidence that the cell-free viral quasispecies in the genital compartment probably arose from PL. Such a flow could gradually create a cellular reservoir of the virus2, which could emerge in case of a break from antiretroviral treatment28. This may also be true for saliva based on our analysis. However, more studies are necessary to determine the presence of a viral reservoir in SAL.

We found evidence of compartmentalization in two of the patients, according to the compartmentalization tests and the phylogenetic analysis of the haplotypes. In these patients, WB and PL were the compartments that present the greatest diversity of haplotypes and reads. The haplotypes of these compartments provide evidence of positive selection probably as a response to the action of neutralizing antibodies29. Generalized linear mixed models didn’t identify differential pressure between the compartments of the patients in late Fiebig stage. This result could be due to the small number of patients.

The genetic homogeneity of the viral population in primary infection, independent of the compartment, has relevant implications for treatment of the disease. The latest proposed therapies aim to boost the response of the immune system using vectors such as DNA, recombinant virus, or dendritic cells30. Some have focused on the first stages of infection, such as the canarypox vaccine, without significant results31. However, approaches that simultaneously address the primary and secondary immune response, such as dendritic cells, could achieve better results.

Our study had several limitations. A longitudinal study is probably better adapted for the analysis of diversity and the evaluation of compartmentalization. Indeed, obtaining samples at various timepoints would allow a detailed analysis of the population dynamics within and between compartments. We also did not have homogeneous representation of patients in the different Fiebig stages and there were large differences in the number of samples available for the various compartments. Although these limitations may have introduced biases, we believe that more representative sampling would confirm our results.

UDS technique required quality correction before analyses; such correction may possibly affect the diversity. So, we compare our diversity data with previous work also using amplification of HIV env region (C2V3) with UDS and focusing on chronically infected patients32,33. These studies find higher diversity than our study on several compartments (blood, plasma semen and CSF) with a similar methodological approaches and quality correction. These data suggest that our methodological approach is able to identify high diversity in compartment.

In conclusion, we evaluated the genetic compartmentalization of the HIV population in plasma, whole blood, saliva, non-spermatic cells, and seminal fluid in patients with primary HIV infection. This study found a low C2V3 diversity in the first stages of infection and the rapid establishment of cellular reservoirs of the virus. Such clonality could be exploited in the search for early patient-specific therapeutic solutions.

Methods

Study population

Eight patients were diagnosed at the time PHI in the department of infectious diseases in Saint-Louis Hospital, Paris, between July and October 2017. PHI was confirmed by one of the following criteria: (i) positive 4th generation HIV-1 ELISA with a negative or incomplete western blot (no anti-p68 or anti-p34) or (ii) positive p24-antigen ELISA and positive for HIV-1 RNA with a negative western blot. Patients were further categorized using adapted Fiebig (F) stages34 as follows: FI: HIV RNA+, p24−, antibody EIA−, WB−; FII: HIV RNA+, p24+, antibody EIA−, WB−; FIII: HIV RNA+, p24+, antibody EIA+, WB−; FIV: HIV RNA+, p24+/−, antibody EIA+, indeterminate WB (<3 antibodies or <2 specific antibodies from among gp160, gp120, and gp41); FV: HIV RNA+, p24+/−, antibody EIA+, WB+ (≥3 antibodies and ≥2 specific antibodies, without the p34 band); and FVI: HIV RNA+, p24+/−, antibody+, complete WB. All were treatment-naive participants at enrollment. The presence and timing of onset of symptoms consistent with PHI were determined by examination of medical records and patient interview.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The study protocol was approved by the Paris Saint Louis Ethics Committee, and all patients gave their written informed consent.

Guidelines followed statement

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Clinical samples

Samples from various compartments (blood, semen, seminal fluid, and saliva) were obtained on the same day. All samples were processed and stored at −80 °C within 4 h of collection.

Quantification of HIV DNA and RNA

HIV-1 RNA was quantified in plasma, seminal fluid, and saliva using the AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HIV v.2 with a limit of quantification of 20, 100, and 60 copies/ml, respectively. Total cell-associated HIV-1 DNA was quantified in whole blood and non-spermatozoid cells as described elsewhere (detection threshold of three copies/PCR)35. Results for whole blood are reported as HIV-1 DNA copy number/106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), taking into account the white blood cell number and the blood formula. Results for non-spermatozoid cells are reported as HIV-1 DNA copy number/106 cells.

env V3 sequence analysis

HIV-1 RNA was extracted from plasma, seminal fluid, and saliva using the EasyMag (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HIV-1 DNA was extracted from whole blood and non-spermatozoid cells using the QiaSymphony DSP DNA protocol « blood » (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf. France). The C2V3 env gene between positions 7008–7385 of the reference sequence HXB2 was amplified using the ANRS protocol (http://www.hivfrenchresistance.org/ANRS-procedures.pdf). Amplicons were multiplexed and used for UDS on a Roche/454 GS. Amplicons were quantified, fixed onto microbeads, subjected to emulsion PCR, and the beads loaded onto picotiter plates for forward and reverse pyrosequencing by means of the GS-FLX Titanium Kit in a Roche 4.5.4 GS Junior sequencer (454 Life Sciences, Roche Diagnostics Corp., Brandford, Connecticut). HIV 8E5 cells harboring one copy of HIV per genome were sequenced as a control to establish the error cut off.

Bioinformatic analysis

Read filtering and de novo viral contigs

Demultiplexing was performed with the FASTX tool kit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/), the adapters removed using Cutadapt36, and regions of low quality (phred score <20) removed using Trimmomatic37. Sequences with a minimum length of 40 bp were retained and used for the de novo assembly using Vicuna software38. De novo contigs were aligned using IndelFixer software (https://github.com/cbg-ethz/InDelFixer) to the respective reference according to the HIV subtype (HXB2 for subtype B and L39106.1 for CRF02_AG). The consensus sequences were obtained for each compartment using ConsensusFixer 0.4 software (https://github.com/cbg-ethz/ConsensusFixer).

Viral haplotype and phylogenetic analysis

The filtered reads were aligned to consensus sequences obtained in the last step using ngshmmalign software (https://github.com/cbg-ethz/ngshmmalign). The haplotypes were identified using the amplian.py script of the ShoRAH project39. Only haplotypes with a posterior probability > 95% were retained.

Multiple alignments of all the haplotypes of the same individual were built using mafft software40. The best sequence evolution model (lowest BIC) was identified using MEGA741. This model was used as a parameter for MrBayes software in the phylogenetic tree identification42. Phylogenetic trees were represented with ggplot2 packages43 in R44.

Mean overall diversity

Reads of each of the compartments were aligned to reference sequences according to subtype45 using BWA software. The diversity was calculated using TN93 software (https://github.com/spond/TN93), which computes Tamura Nei pairwise distances between aligned sequences.

Generalized linear mixed model

The potential differential pressure between compartments was evaluated with a generalized linear mixed models. In these models the patients were the random effect while the compartments and the Fiebig stage were fixed effect predictors of diversity. In the first model, the analysis was limited to Fiebig stage IV and V patients. In the second model, the Fiebig stage IV and V patients were regrouped into a stage called “Later” and the only Fiebig stage II patient represents the “Early” stage. The random effects models were compared to a model of only fixed effects with the ANOVA test. The Markdown report in R is presented in the Supplementary Note S1.

Positive selection and N-glycosylation

Amino-acid changes under positive selection were identified in the multiple alignments of the haplotypes in each patient using the CorMut R package (load ≥2 & frequency of mutation > 0.01). Potential N-glycosylation sites were identified using N-Glycosite46, (https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/GLYCOSITE/glycosite.html).

Compartmentalization analysis

Viral compartmentalization was evaluated by computing using both distance-based (fixation index, Fst)47 and tree-based methods (Simmonds association index, Slatkin and Maddisson test, and correlation coefficient)48. The Fst was calculated using TN93 genetic distance (https://github.com/spond/TN93). Statistical significance was assessed via a 100-population permutation. We made clusters of reads using the cd-hit-est tool49 with the aim of reducing the potential influence of amplification errors. The representative sequence of each cluster was used to perform a second estimation of the Fst. The Slatkin and Maddison test was performed using Hyphy software50.

The p-values were estimated from 10,000 permutations of haplotypes between the compartments. P-values were corrected using Bonferroni correction. Populations among various compartments were defined as being compartmentalized if the three compartmentalization tests were significant (P < 0.0001).

References

Soriano, V. The Source of New HIV Infections are People not being Treated or Unaware of their Status. AIDS Rev 21, 108–109 (2019).

Chéret, A. et al. Impact of early cART on HIV blood and semen compartments at the time of primary infection. PLoS ONE 12, e0180191 (2017).

Pilcher, C. D. et al. Brief but efficient: acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. J. Infect. Dis. 189, 1785–1792 (2004).

Quinn, T. C. et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 921–929 (2000).

Wawer, M. J. et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J. Infect. Dis. 191, 1403–1409 (2005).

Blackard, J. T. HIV compartmentalization: a review on a clinically important phenomenon. Curr. HIV Res. 10, 133–142 (2012).

Keele, B. F. et al. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7552–7557 (2008).

McNearney, T. et al. Relationship of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 sequence heterogeneity to stage of disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 10247–10251 (1992).

Haaland, R. E. et al. Inflammatory genital infections mitigate a severe genetic bottleneck in heterosexual transmission of subtype A and C HIV-1. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000274 (2009).

Zhang, Z.-Q. et al. Roles of substrate availability and infection of resting and activated CD4+ T cells in transmission and acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 5640–5645 (2004).

Galvin, S. R. & Cohen, M. S. The role of sexually transmitted diseases in HIV transmission. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 33–42 (2004).

Darcis, G., Coombs, R. W. & Van Lint, C. Exploring the anatomical HIV reservoirs: role of the testicular tissue. AIDS 30, 2891–2893 (2016).

Price, R. W. et al. Evolving character of chronic central nervous system HIV infection. Semin Neurol 34, 7–13 (2014).

Abrahams, M.-R. et al. Quantitating the multiplicity of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C reveals a non-poisson distribution of transmitted variants. J. Virol. 83, 3556–3567 (2009).

Anderson, J. A. et al. HIV-1 Populations in Semen Arise through Multiple Mechanisms. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001053 (2010).

Klein, K. et al. Higher sequence diversity in the vaginal tract than in blood at early HIV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006754 (2018).

Byrn, R. A. & Kiessling, A. A. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus in semen: indications of a genetically distinct virus reservoir. J. Reprod. Immunol. 41, 161–176 (1998).

Gupta, P. et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 shedding pattern in semen correlates with the compartmentalization of viral Quasi species between blood and semen. J. Infect. Dis. 182, 79–87 (2000).

Eyre, R. C., Zheng, G. & Kiessling, A. A. Multiple drug resistance mutations in human immunodeficiency virus in semen but not blood of a man on antiretroviral therapy. Urology 55, 591 (2000).

Grebe, E. et al. Interpreting HIV diagnostic histories into infection time estimates: analytical framework and online tool. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 894 (2019).

Tamura, K. & Nei, M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10, 512–526 (1993).

Stekler, J. et al. HIV dynamics in seminal plasma during primary HIV infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 24, 1269–1274 (2008).

Phanuphak, N. et al. Anogenital HIV RNA in Thai men who have sex with men in Bangkok during acute HIV infection and after randomization to standard vs. intensified antiretroviral regimens. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 18, 19470 (2015).

Baggaley, R. F., White, R. G. & Boily, M.-C. Infectiousness of HIV-infected homosexual men in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 24, 2418–2420 (2010).

Ikeno, R. et al. Factors contributing to salivary human immunodeficiency virus type-1 levels measured by a Poisson distribution-based PCR method. J. Int. Med. Res. 46, 996–1007 (2018).

Shugars, D. C. et al. Saliva and inhibition of HIV-1 infection: molecular mechanisms. Oral Dis 8(Suppl 2), 169–175 (2002).

Tully, D. C. et al. Differences in the Selection Bottleneck between Modes of Sexual Transmission Influence the Genetic Composition of the HIV-1 Founder Virus. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005619 (2016).

Palich, R. et al. Viral rebound in semen after antiretroviral treatment interruption in an HIV therapeutic vaccine double-blind trial. AIDS 33, 279–284 (2019).

Ho, Y. S. et al. HIV-1 gp120 N-linked glycosylation differs between plasma and leukocyte compartments. Virol. J. 5, 14 (2008).

García, F. et al. Dendritic cell based vaccines for HIV infection. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 9, 2445–2452 (2013).

Papagno, L. et al. Comprehensive analysis of virus-specific T-cells provides clues for the failure of therapeutic immunization with ALVAC-HIV vaccine. AIDS 25, 27–36 (2011).

Chaillon, A. et al. Characterizing the multiplicity of HIV founder variants during sexual transmission among MSM. Virus. Evol. 2 (2016).

Oliveira, M. F. et al. Early Antiretroviral Therapy Is Associated with Lower HIV DNA Molecular Diversity and Lower Inflammation in Cerebrospinal Fluid but Does Not Prevent the Establishment of Compartmentalized HIV DNA Populations. PLOS Pathogens 13, e1006112 (2017).

Fiebig, E. W. et al. Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. AIDS 17, 1871–1879 (2003).

Delaugerre, C. et al. Time course of total HIV-1 DNA and 2-long-terminal repeat circles in patients with controlled plasma viremia switching to a raltegravir-containing regimen. AIDS 24, 2391–2395 (2010).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal; Vol 17, No 1: Next Generation Sequencing Data Analysis, https://doi.org/10.14806/ej.17.1.200 (2011).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Yang, X. et al. De novo assembly of highly diverse viral populations. BMC Genomics 13, 475 (2012).

Zagordi, O., Bhattacharya, A., Eriksson, N. & Beerenwinkel, N. ShoRAH: estimating the genetic diversity of a mixed sample from next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 119 (2011).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. - PubMed – NCBI, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27004904.

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer-Verlag, 2009).

R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2014).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Zhang, M. et al. Tracking global patterns of N-linked glycosylation site variation in highly variable viral glycoproteins: HIV, SIV, and HCV envelopes and influenza hemagglutinin. Glycobiology 14, 1229–1246 (2004).

Hudson, R. R., Slatkin, M. & Maddison, W. P. Estimation of levels of gene flow from DNA sequence data. Genetics 132, 583–589 (1992).

Slatkin, M. & Maddison, W. P. A cladistic measure of gene flow inferred from the phylogenies of alleles. Genetics 123, 603–613 (1989).

Li, W., Jaroszewski, L. & Godzik, A. Clustering of highly homologous sequences to reduce the size of large protein databases. Bioinformatics 17, 282–283 (2001).

Pond, S. L. K., Frost, S. D. W. & Muse, S. V. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics 21(5), 676–679 (2005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML. Chaix, G. Gaube, C. Delaugerre, and C. Lascoux Combe developed the study design. C. Lascoux Combe, S. Galien, and JM. Molina recruited the patients. G. Gaube, ML Nérè, N. Mahjoub and A. Gabassi performed the virological analysis. A. Armero analyzed the data and generated the figures. A. Armero, C. Delaugerre, G. Gaube, M. Salmona, A. Amara and ML. Chaix wrote the manuscript. All authors provided critical input and approved the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaube, G., Armero, A., Salmona, M. et al. Characterization of HIV-1 diversity in various compartments at the time of primary infection by ultradeep sequencing. Sci Rep 10, 2409 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59234-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59234-6

- Springer Nature Limited