Abstract

Visible-light photocatalysis has evolved as a powerful technique to enable controllable radical reactions. Exploring unique photocatalytic mode for obtaining new chemoselectivity and product diversity is of great significance. Herein, we present a photo-induced chemoselective 1,2-diheteroarylation of unactivated alkenes utilizing halopyridines and quinolines. The ring-fused azaarenes serve as not only substrate, but also potential precursors for halogen-atom abstraction for pyridyl radical generation in this photocatalysis. As a complement to metal catalysis, this photo-induced radical process with mild and redox neutral conditions assembles two different heteroaryl groups into alkenes regioselectively and contribute to broad substrates scope. The obtained products containing aza-arene units permit various further diversifications, demonstrating the synthetic utility of this protocol. We anticipate that this protocol will trigger the further advancement of photo-induced alkyl/aryl halides activation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

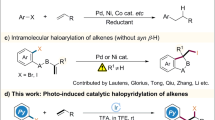

The past decades have witnessed the evolution of visible-light photocatalysis1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 as a powerful tool to enable controllable radical reactions. Photocatalytic single electron transfer (SET)10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 and energy transfer (EnT)18,19,20,21,22,23,24 are two principle modes of action to handle chemoselective reactions by generating active radical species (Fig. 1a). Among them, photoredox SET (oxidative or reductive quenching) is to induce an electron transfer to or from a reagent (A, D or S), thus generating the radical. The EnT process involves a photosensitizer transferring energy to a substrate (S), resulting highly reactive triplet state intermediate. Based on these instructions, significant strategies have been employed for divergent heteroarylation of alkenes under photocatalysis utilizing simple halopyridines or quinolines (Fig. 1b). For example, Jui’s group developed anti-Markovnikov hydroarylation methods for alkenes by incorporating Hantzsch ester (HEH) as quencher via reductive quenching process25,26,27. In our previous work, an atom-economical halopyridylation of alkenes was achieved by introducing additional TFA to regulate the oxidative quenching pathway28. The protonated halopyridine as the switchable quencher could be directly reduced by exited state *IrIII. In addition, Glorius, Houk, Brown, etc. disclosed the EnT–mediated intermolecular dearomative cycloaddition reactions of quinolines with alkenes29,30,31, where quinolines activated by acid served as an effective quencher. Despite the significant progress made, developing unique photocatalytic modes for obtaining new chemoselectivity is of great significance, especially stemming from multicomponent halopyridine, alkene, and quinoline.

The rapid access to complex molecules from simple substrates is a crucial topic in synthetic chemistry. Polyarylalkanes are a class of important skeletons in natural products, pharmaceutical molecules, and advanced materials, which have attracted long-standing interests32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Recently, transition-metal catalyzed 1,2-diarylation of alkenes represents an effective strategy for the preparation of 1,2-diarylalkanes, representative works have been reported by Giri, Engle, Brown, Koh, Kong etc40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48. Li’s group developed an electrochemical Co-catalyzed 1,2-diheteroarylation of styrenes enabled by dual C–H functionalizations of indoles49. However, substrates of the above works are usually restricted to alkenes that contain directing groups or conjugated aryls, and N-heteroaryl groups are also scarce because the coordinating nitrogen atom of azaaromatics tends to either deactivate the catalyst or interfere with the reaction selectivity. Hence, the catalytic 1,2-diheteroarylation of unactivated alkenes is expected to gain broad appeal but remains underdeveloped.

Given that complex products can be achieved by leveraging radical domino processes50,51,52,53, photo-induced Minisci reactions54,55,56,57,58,59 and our interest in photocatalytic (hetero)aryl halides activation28,60,61, we questioned whether photocatalysis can address the challenges above and produce 1,2-diheteroarylalkanes from halopyridine, quinoline and alkene. In this context, it is challenging to keep the balance between the activation of halopyridines and ring-fused aza-arenes under the same acidic system, also not disturbing photocatalysis. The acidic system is a crucial factor but likely undergoes dynamic changes during the transformations. In addition, the effective quencher of excited-state photocatalysts is uncertain between halopyridine and ring-fused azaarene, which may affect the chemoselectivity. Herein, we present a visible light-induced chemoselective 1,2-diheteroarylation of alkenes from halopyridine, alkene, and ring-fused azaarene (Fig. 1c). Notably, the ring-fused azaarenes serve as not only substrate but also potential precursors for halogen-atom abstraction for the generation of pyridyl radicals.

Results and discussion

Our investigation commenced with screening various Brønsted acid additives for the model reaction among 2-bromopyridine 1a, TMS-substituted alkene 2a, and 4-methylquinoline 3a. To our delight, weak organic acids could lead to desired product 4aa up to 90% yield in the condition of Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2PF6 (Ir-I) and TFE (2,2,2-Trifluoroethanol) under blue LEDs irradiation (Fig. 2a). But strong organic acids, such as TsOH and TFA gave bad performance, which is indispensable to our previous halopyridine activation. Exploration of certain photocatalysts with varying properties was conducted, and product yields were correlated to redox properties of photocatalysts while unrelated to triplet state energy (Fig. 2b)2. These results implied a SET pathway rather than EnT process of this reaction. Moreover, ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectroscopy of all reactants and their mixtures demonstrated that photocatalyst Ir-I acted as the only absorbing species among the wavelength range covered by Kessil light source (λmax = 456 nm) (Fig. 2c). Subsequently, to understand the nature of this interaction, fluorescence quenching experiments and Stern-Volmer analysis were conducted (Fig. 2d). As an interesting result, the luminescence emission of photocatalyst was quenched effectively by [3a + AcOH] mixture instead of [1a + AcOH], indicating that an interaction between photocatalyst and [3a + AcOH] mixture might exist to promote this reaction. Meanwhile, the addition of strong acid TsOH could regulate 2-bromopyridine 1a to be an effective quencher, but AcOH may not be acidic enough to activate 2-bromopyridine 1a for interacting with the exited state [Ir-I]*. The results above hinted at an exclusive SET process between photocatalyst and activated quinoline.

a Effect of Brønsted acid additives on model reaction. b Systematic evaluation of various photocatalysts. c UV-vis absorption spectroscopy. d Stern-Volmer quenching studies. e Evaluation of other reaction parameters. aPredicted pKa value. MCAA chloroacetic acid. bReaction conditions: 1a (0.20 mmol), 2a (0.50 mmol), 3a (0.10 mmol), PC [Ir-I] (2.0 mol%), AcOH (0.10 mmol), TFE (2.0 mL), blue LEDs (λmax = 456 nm), room temperature, N2 atmosphere, 20 h, yields were determined by GC-FID analysis of the crude reaction mixture using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard. cYields were calculated based on 1a.

Then, the impact of other parameters was also examined (Fig. 2e). The product yield of 4aa decreased from 90% to 20% when AcOH was removed from the reaction condition (Fig. 2e, entries 1, 2). As expected, this reaction cannot proceed in the absence of either Iridium photocatalyst or blue light (Fig. 2e, entry 3). Interestingly, excess TsOH (2.0 eq.) as a replacement for AcOH changed the chemoselectivity, producing bromopyridylation side-product 5 in 41% yield with no product 4aa observed (Fig. 2e, entry 4). Another strongly polar protic solvent HFIP (Hexafluoroisopropanol) afforded just 13% yield of product 4aa (Fig. 2e, entry 5). Alcohols or common organic solvents, such as MeOH, EtOH, and MeCN, were all not feasible (Fig. 2e, entry 6 and Supplementary Table 3 in Supplementary information). Moreover, common organophotocatalysts, Ru-photocatalysts, and Ir(ppy)3 (Ir-II) exhibited bad catalytic performance (Fig. 2e, entry 7 and Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary information). Ir-photocatalysts with high triple-state energy, such as Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6 (Ir-III) and Ir[dF(Me)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6 (Ir-IV) could switch the chemoselectivity to afford dearomatization side-product 6 with up to 62% yield (Fig. 2e, entry 8). The Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2PF6 (Ir-I) complex proved to be the most suitable catalyst for this reaction. To our satisfactory, product 4aa could be obtained at 93% yield with the decreasing of photocatalyst dosage to 0.5 mol%, and still at 86% yield with only 0.1 mol% photocatalyst (Fig. 2e, entry 9). This reaction appeared to be less sensitive to the water (Fig. 2e, entry 10).

With the optimized reaction conditions established, the generality of photocatalytic multi-component 1,2-diheteroarylation was explored, involving N-heteroaromatics scope (Fig. 3) and simple alkenes scope (Fig. 4). Initially, N-heteroarenes, including a series of quinolines (4aa–4aj), isoquinolines (4ak and 4al) and phenanthridine (4am) were subjected to the optimized conditions (Fig. 3). The results demonstrated that quinolines bearing methyl or steric isopropyl, cyclohexyl substituents at either the C-2 or C-4 position proceeded smoothly with good regioselectivities (4aa–4ah), while phenyl, ester and halo groups were not tolerated (Supplementary Fig. 1 in Supplementary information). In addition, 2-methyl-6-bromo-quinoline was an applicable heteroarene substrate, delivering corresponding product 4af in 70% yield. The aforementioned results may be caused by electron-withdrawing substituents on N-containing aromatic rings altering the redox capacity of the quinoline, thereby disrupting the electron transfer. To our delight, the 3-methoxyquinoline exhibited good regioselectivity at C-2 position, affording the product 4ai in 72% yield with >20:1 rr. Unsubstituted quinoline furnished mixtures of C-2/C-4 regioisomers (4aj and 4aj’) in comparable yields. Under optimized conditions, the isoquinoline-based product 4ak (48% yield) was apt to overly react with alkene 2a, leading to some further dearomative cycloaddition product 4ak’ (34% yield). Interestingly, when 5-bromoisoquinoline 3 l was subjected to this reaction, the inherent C−Br bond of resulting 1,2-diheteroarylation product was completely substituted by allyl group (4al). Reaction with phenanthridine could give product 4am in a high yield (92%). Other aza-arenes such as pyridine, pyrazine, and pyrimidine were also explored, but afforded desired products in low yields (Supplementary Fig. 1 in Supplementary information).

Next, we turned to explore other halopyridines. As shown in Fig. 3, 2-bromopyridines substituted by methyl or methoxy at different positions performed well to produce target products 4ba–4ga in good to high yields under optimized conditions. A wide range of 4-bromopydines substrate reacted regioselectively at the C-4 position to deliver products in 71-81% yields (4ha–4ka). Bromopyridines containing sensitive functional groups, such as hydroxymethyl and hydroxyl, were also tolerated (4la–4na). Gratifyingly, 4oa and 4pa bearing trifluoromethyl as strong electron-withdrawing groups could also be isolated in 73% and 84% yields, respectively. The structure of 4oa has been further confirmed by single-crystal X-ray crystallography (CCDC: 2296361). Moreover, dihalopyridines were also examined, and the reaction selectively took place at the C-2 position with the preservation of 3-Cl/Br (4qa and 4sa) or 5-Cl (4ra) group for further synthetic elaboration. Notably, 4-Bromo-7-azaindole as diazo aryl halides was also reactive to afford 1,2-diheteroarylation product 4ta in 55% yield.

The applicability of this protocol toward alkenes scope was investigated (Fig. 4). Simple α-olefins were successfully diheteroarylated with moderate to good yields (7a–7k). Among that, various functional groups, such as halide, benzenesulfonyl, acetyl, ester, and phenyl, were all feasible, but alkenes with electron-withdrawing substituents exhibited relatively low reactivity. Styrene was not suitable for this reaction (7l). Alternatively, enol ethers were also examined, but only delivered 45% yield of product 7m. On the other hand, even 1,1-disubstituted alkenes (7n–7q) and internal alkenes (7r–7t) could be diheteroarylated regioselectively. For example, steric (7n and 7o) or hydroxyl-substituted (7p) alkenes reacted smoothly to deliver corresponding products in 54–71% yields. Trisubstituted alkene participated in the production of a single product 7r in 64% yield with high regioselectivity. Moreover, cyclopentene and cyclohexene as cyclic internal alkenes performed well, producing 77% (7s) and 86% (7t) yields of products, respectively, with excellent diastereoselectivities (>20:1 dr).

To gain deep insights into this chemoselective 1,2-diheteroarylation, more mechanistic studies were performed (Fig. 5). First, the impact of varying amounts (0.2 ~ 2.0 eq.) of TsOH or AcOH on the model reaction was examined respectively (Fig. 5a). With the increase of TsOH dosage, the chemoselectivity shifted from the desired product 4aa to side-product 5, while AcOH dosage has only a slight effect on yield of 4aa, implying that the suitable strength or concentration of Brønsted acids is of the utmost importance. These results are consistent with the Stern-Volmer quenching studies above (Fig. 2d). Second, the electrochemical analysis experiments were further conducted to understand the photoredox process. As shown in Fig. 5b, the cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurement of 4-methylquinoline 3a indicated its reductive potential as −1.39 V vs. SCE in TFE (green line), and the addition of AcOH (1.0 equiv.) raised a sharper reduction peak of the [3a + AcOH] mixture to −1.24 V vs. SCE (blue line). Upon switching the solvent to MeCN, the reduction potential of the [3a + AcOH] mixture decreased to −1.41 V vs. SCE in MeCN (orange line). These results suggested that AcOH and TFE could effectively increase the redox potential of aza-arenes 3a to be more easily reduced. Furthermore, no reduction peak was observed in the [1a + AcOH] mixture before −2.0 V vs. SCE in TFE (gray line), while the mixture of [1a + TsOH] delivered a reduction potential as −1.38 V vs. SCE (pink line). Hence, it can be inferred that quinoline is more easily reduced than bromopyridine under AcOH/TFE conditions, while bromopyridine could also exhibit competitiveness if the acidity of the system is sufficiently strong.

Besides, the addition of radical scavenger TEMPO or BHT to the model reaction resulted in suppression of product generation (Fig. 5c). And two BHT-adducts, Int-B and Int-C, were successfully detected. These results indicate that pyridyl radical and secondary carbon-centered radical are probably formed in the transformation. Then, light on/off experiments showed that this transformation proceeded only under light irradiation, and the quantum yield of the model reaction was determined as 0.87, which might exclude the radical chain process (Fig. 5d). Notably, kinetic studies of 1a, 2b and 3a under standard conditions were tested (Fig. 5e). As more 1,2-diheteroarylation product 7a generated, there was a slight accumulation of Heck-type side-product 9, but with no observation of bromopyridylation side-product 8. In the end, the pure 8 and 9 were resubjected to the standard conditions. As expected, 8 could react with 3a to produce products 7a and 9 in 45% and 6% yields, respectively, but 9 did not react. So, it is inferred that bromopyridylation side-products may be generated in the transformation but will be quickly activated to produce target 1,2-diheteroaryl products. Besides, supplementary control experiments demonstrated that quinoline 3/3’ might interact with 1 to promote the generation of pyridyl radical (Supplementary Fig. 23 in Supplementary information).

Based on the combined results and related literatures62,63,64,65,66, a possible mechanism is proposed as outlined in Fig. 6a. This reaction commences with the activation of photocatalyst IrIII to generate the excited state *IrIII. Then, under AcOH/TFE conditions, the SET between excited state *IrIII and protonated quinoline 3 creates oxidized IrIV and heteroarene-centered radical 3’. The excited state *Ir-I was reported as having *E1/2ox = −0.96 V (vs. SCE), which is a standard value in MeCN67. However, there will be a large variation in the redox property of photocatalysts in the presence of different solvents68. In this case, the experimental *E1/2ox of Ir-I in TFE was measured as *E1/2ox = −1.54 V (vs. SCE) (Section 7.11 in Supplementary information). It suggests that the SET between *IrIII and protonated quinoline 3 (E1/2red = −1.24 V vs. SCE) is feasible. After that, the reduced radical 3’ is strongly nucleophilic like the α-aminoalkyl radical, which is able to promote the homolytic activation of carbon-halogen bond65,66. In this protocol, intermediate 3’ might serve as a halogen abstracting reagent to activate bromopyridine 1, producing the pyridyl radical Int-I (Supplementary Fig. 28 in Supplementary information). This assumption has been supported by the corresponding control experiments between 4-methylquinoline and alkyl halides (Supplementary Fig. 27 in Supplementary information). The electrophilic radical Int-I selectively couples with unactivated alkene 2 to furnish nucleophilic carbon-centered radical Int-II. Then, the obtained radical Int-II undergoes nucleophilic addition onto heteroarene 3 to generate radical cation Int-III. Finally, deprotonation and oxidation of Int-III by the IrIV gives rise to target 1,2-diheteroaryl product 4 and regenerates photocatalyst IrIII. In addition, an alternative SET between alkyl radical Int-II (E1/2Ox = 0.47 V)69 and IrIV (experimental E1/2red = 0.98 V vs. SCE, Supplementary Fig. 25 in Supplementary information) is electrochemically feasible to generate carbocation Int-IV, then affords bromopyridylation side-product 5 or 8. Notably, based on the control experiment (Fig. 5e), alkyl halide 8 could also be activated to produce target 1,2-diheteroarylation product 7a. The proposed mechanism for the generation of side-products 528 and 629 are also described (Section 7.10 in Supplementary information).

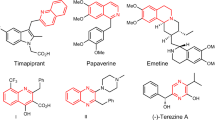

In order to further demonstrate the synthetic utility of this protocol, scale-up reactions alone with transformations of 1,2-diheteroaryl products were performed (Fig. 6b). Initially, 1,2-diheteroaryl products 4aa, 7q, and 4al were successfully synthesized on 4.0 mmol scale without obvious loss of the yield. Then, the transformation was started with the oxidation of pyridine and quinoline moieties under mCPBA conditions70. Through stepwise addition of mCPBA at low temperature (−10 °C), pyridine single N-oxide 10 could be obtained in moderate yield. Bis-N-oxide 11 was also conveniently prepared in 93% yield, which underwent the subsequent photochemical carbon extrusion to deliver N-acylindole 12 via UV-light irradiation71. The intrinsic N-oxide reactivity could enable further diverse transformations of 10 and 12. Moreover, photo-induced dearomatization of quinoline moiety of 4aa and 7q were accomplished, such as dearomative cycloaddition29, hydrosilylation, and reduction72, leading to partially saturated heteroarenes 13–15 in good yields (76–89%). These remaining double bonds after dearomatization represent another versatile, functional group to be further decorated.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a visible light-induced catalytic 1,2-diheterarylation of unactivated alkenes in high chemo- and regioselectivities. The developed AcOH/TFE/Ir-I conditions are efficient for regulating the chemoselectivity through a unique mode for pyridyl radical generation, where the ring-fused aza-arenes serve as not only substrate but also precursors for potential halogen-atom abstraction in this photocatalysis. As a complement to metal catalysis methods, this photocatalytic radical process contributes to a broad substrate scope under mild conditions. In addition, the synthetic utility of the 1,2-diheteroaryl products was demonstrated in scale-up experiments and diverse transformations. A series of mechanistic studies were conducted to support the plausible mechanism. Further in-depth research and application are on the schedule in our group.

Methods

General procedures for chemoselective 1,2-diheteroarylation of alkenes under photocatalysis

To an oven-dried 20 mL vial was added Ir(ppy)2(dtbbpy)PF6 (0.002 mmol, 0.5 mol%), bromopyridine 1 (0.80 mmol, 2.0 eq.), alkene 2 (2.0 ~ 2.8 mmol, 5.0 ~ 7.0 eq.), quinoline 3 (0.40 mmol, 1.0 eq.), AcOH (0.40 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and TFE (8.0 mL, 0.05 M) in a nitrogen glove box. The vial was capped with a septum and wrapped with parafilm. The reaction mixture was stirred for 20 h under visible light irradiation (Kessil PR160, λmax = 456 nm, 40 W, irradiation temperature maintained between 25–30 °C). Upon completion, the crude product was neutralized with saturated NaHCO3 solution or Et3N and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layer was washed with brine solution and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Removal of the organic solvent in a vacuum rotavapor followed by flash silica gel column chromatographic purification afforded the desired product 4 or 7.

Data availability

Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center under deposition numbers CCDC 2296361 (4oa). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Data relating to the characterization data of materials and products, general methods, optimization studies, experimental procedures, mechanistic studies, and NMR spectra are available in the Supplementary information. All data are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Yoon, T. P., Ischay, M. A. & Du, J. Visible light photocatalysis as a greener approach to photochemical synthesis. Nat. Chem. 2, 527–532 (2010).

Prier, C. K., Rankic, D. A. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Visible light photoredox catalysis with transition metal complexes: Applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 113, 5322–5363 (2013).

Twilton, J. et al. The merger of transition metal and photocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0052 (2017).

Marzo, L., Pagire, S. K., Reiser, O. & Koenig, B. Visible-light photocatalysis: Does it make a difference in organic synthesis? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 10034–10072 (2018).

Chen, Y., Lu, L.-Q., Yu, D.-G., Zhu, C.-J. & Xiao, W.-J. Visible light-driven organic photochemical synthesis in china. Sci. China Chem. 62, 24–57 (2019).

Sakakibara, Y. & Murakami, K. Switchable divergent synthesis using photocatalysis. ACS Catal. 12, 1857–1878 (2022).

Lee, W., Park, I. & Hong, S. Photoinduced difunctionalization with bifunctional reagents containing N-heteroaryl moieties. Sci. China Chem. 66, 1688–1700 (2023).

Matsuo, B., Granados, A., Levitre, G. & Molander, G. A. Photochemical methods applied to DNA encoded library synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 385–401 (2023).

Wortman, A. K. & Stephenson, C. R. J. EDA photochemistry: Mechanistic investigations and future opportunities. Chem 9, 2390–2415 (2023).

Narayanam, J. M. R. & Stephenson, C. R. J. Visible light photoredox catalysis: Applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 102–113 (2011).

Romero, N. A. & Nicewicz, D. A. Organic photoredox catalysis. Chem. Rev. 116, 10075–10166 (2016).

Shaw, M. H., Twilton, J. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Photoredox catalysis in organic chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 81, 6898–6926 (2016).

Skubi, K. L., Blum, T. R. & Yoon, T. P. Dual catalysis strategies in photochemical synthesis. Chem. Rev. 116, 10035–10074 (2016).

Crisenza, G. E. M. & Melchiorre, P. Chemistry glows green with photoredox catalysis. Nat. Commun. 11, 803 (2020).

Zhu, C., Yue, H., Chu, L. & Rueping, M. Recent advances in photoredox and nickel dual-catalyzed cascade reactions: Pushing the boundaries of complexity. Chem. Sci. 11, 4051–4064 (2020).

Chan, A. Y. et al. Metallaphotoredox: The merger of photoredox and transition metal catalysis. Chem. Rev. 122, 1485–1542 (2022).

Engl, S. & Reiser, O. Copper-photocatalyzed ATRA reactions: Concepts, applications, and opportunities. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 5287–5299 (2022).

Michelin, C. & Hoffmann, N. Photosensitization and photocatalysis—perspectives in organic synthesis. ACS Catal. 8, 12046–12055 (2018).

Strieth-Kalthoff, F., James, M. J., Teders, M., Pitzer, L. & Glorius, F. Energy transfer catalysis mediated by visible light: Principles, applications, directions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 7190–7202 (2018).

Zhou, Q.-Q., Zou, Y.-Q., Lu, L.-Q. & Xiao, W.-J. Visible-light-induced organic photochemical reactions through energy-transfer pathways. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 1586–1604 (2019).

Strieth-Kalthoff, F. & Glorius, F. Triplet energy transfer photocatalysis: Unlocking the next level. Chem 6, 1888–1903 (2020).

Großkopf, J., Kratz, T., Rigotti, T. & Bach, T. Enantioselective photochemical reactions enabled by triplet energy transfer. Chem. Rev. 122, 1626–1653 (2022).

Neveselý, T., Wienhold, M., Molloy, J. J. & Gilmour, R. Advances in the E→Z isomerization of alkenes using small molecule photocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 122, 2650–2694 (2022).

Lee, W., Koo, Y., Jung, H., Chang, S. & Hong, S. Energy-transfer-induced [3+2] cycloadditions of N–N pyridinium ylides. Nat. Chem. 15, 1091–1099 (2023).

Aycock, R. A., Vogt, D. B. & Jui, N. T. A practical and scalable system for heteroaryl amino acid synthesis. Chem. Sci. 8, 7998–8003 (2017).

Boyington, A. J., Riu, M.-L. Y. & Jui, N. T. Anti-Markovnikov hydroarylation of unactivated olefins via pyridyl radical intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 6582–6585 (2017).

Seath, C. P., Vogt, D. B., Xu, Z., Boyington, A. J. & Jui, N. T. Radical hydroarylation of functionalized olefins and mechanistic investigation of photocatalytic pyridyl radical reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 15525–15534 (2018).

Guo, S.-Y. et al. Photo-induced catalytic halopyridylation of alkenes. Nat. Commun. 12, 6538 (2021).

Ma, J. et al. Photochemical intermolecular dearomative cycloaddition of bicyclic azaarenes with alkenes. Science 371, 1338–1345 (2021).

Guo, R. et al. Photochemical dearomative cycloadditions of quinolines and alkenes: Scope and mechanism studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17680–17691 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Facile access to fused 2D/3D rings via intermolecular cascade dearomative [2 + 2] cycloaddition/rearrangement reactions of quinolines with alkenes. Nat. Catal. 5, 405–413 (2022).

Buu-Hoi, N., Delcey, M., Jacquignon, P. & P’erin, F. Further heterocyclic analogs of polyaryls. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 5, 259–262 (1968).

Chen, L., Hernandez, Y., Feng, X. & Müllen, K. From nanographene and graphene nanoribbons to graphene sheets: Chemical synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 7640–7654 (2012).

Hennessy, E. T. & Betley, T. A. Complex N-heterocycle synthesis via iron-catalyzed, direct C–H bond amination. Science 340, 591–595 (2013).

Miao, Q. Polycyclic Arenes and Heteroarenes: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. (John Wiley & Sons, 2015).

Stępień, M., Gońka, E., Żyła, M. & Sprutta, N. Heterocyclic nanographenes and other polycyclic heteroaromatic compounds: Synthetic routes, properties, and applications. Chem. Rev. 117, 3479–3716 (2017).

Grzybowski, M., Sadowski, B., Butenschön, H. & Gryko, D. T. Synthetic applications of oxidative aromatic coupling—from biphenols to nanographenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 2998–3027 (2020).

Choi, J., Laudadio, G., Godineau, E. & Baran, P. S. Practical and regioselective synthesis of C-4-alkylated pyridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 11927–11933 (2021).

Xiong, W. et al. Dynamic kinetic reductive conjugate addition for construction of axial chirality enabled by synergistic photoredox/cobalt catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 7983–7991 (2023).

Urkalan, K. B. & Sigman, M. S. Palladium-catalyzed oxidative intermolecular difunctionalization of terminal alkenes with organostannanes and molecular oxygen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 3146–3149 (2009).

Shrestha, B. et al. Ni-catalyzed regioselective 1,2-dicarbofunctionalization of olefins by intercepting heck intermediates as imine-stabilized transient metallacycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10653–10656 (2017).

Derosa, J. et al. Nickel-catalyzed 1,2-diarylation of simple alkenyl amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 17878–17883 (2018).

Gao, P., Chen, L. A. & Brown, M. K. Nickel-catalyzed stereoselective diarylation of alkenylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10653–10657 (2018).

Anthony, D., Lin, Q., Baudet, J. & Diao, T. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric reductive diarylation of vinylarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 3198–3202 (2019).

Ping, Y., Li, Y., Zhu, J. & Kong, W. Construction of quaternary stereocenters by palladium-catalyzed carbopalladation-initiated cascade reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 1562–1573 (2019).

Chintawar, C. C., Yadav, A. K. & Patil, N. T. Gold-catalyzed 1,2-diarylation of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 11808–11813 (2020).

Derosa, J. et al. Nickel-catalyzed 1,2-diarylation of alkenyl carboxylates: A gateway to 1,2,3-trifunctionalized building blocks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 1201–1205 (2020).

Wang, H., Liu, C.-F., Martin, R. T., Gutierrez, O. & Koh, M. J. Directing-group-free catalytic dicarbofunctionalization of unactivated alkenes. Nat. Chem. 14, 188–195 (2022).

Qin, J.-H., Luo, M.-J., An, D.-L. & Li, J.-H. Electrochemical 1,2-diarylation of alkenes enabled by direct dual C–H functionalizations of electron-rich aromatic hydrocarbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 1861–1868 (2021).

Plesniak, M. P., Huang, H.-M. & Procter, D. J. Radical cascade reactions triggered by single electron transfer. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0077 (2017).

Xuan, J. & Studer, A. Radical cascade cyclization of 1,n-enynes and diynes for the synthesis of carbocycles and heterocycles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 4329–4346 (2017).

Huang, H.-M., Garduño-Castro, M. H., Morrill, C. & Procter, D. J. Catalytic cascade reactions by radical relay. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 4626–4638 (2019).

Holmberg-Douglas, N. & Nicewicz, D. A. Photoredox-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions. Chem. Rev. 122, 1925–2016 (2022).

Cheng, W.-M., Shang, R., Fu, M.-C. & Fu, Y. Photoredox-catalysed decarboxylative alkylation of N-heteroarenes with N-(acyloxy)phthalimides. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 2537–2541 (2017).

Cheng, W.-M., Shang, R. & Fu, Y. Photoredox/Brønsted acid co-catalysis enabling decarboxylative coupling of amino acid and peptide redox-active esters with N-heteroarenes. ACS Catal. 7, 907–911 (2017).

Fu, M.-C., Shang, R., Zhao, B., Wang, B. & Fu, Y. Photocatalytic decarboxylative alkylations mediated by triphenylphosphine and sodium iodide. Science 363, 1429–1434 (2019).

Proctor, R. S. J. & Phipps, R. J. Recent advances in Minisci-type reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13666–13699 (2019).

Zheng, D. & Studer, A. Asymmetric synthesis of heterocyclic γ-amino-acid and diamine derivatives by three-component radical cascade reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 15803–15807 (2019).

Tan, L. et al. Photocatalytic decarboxylative Minisci reaction catalyzed by palladium-loaded gallium nitride. Precis. Chem. 1, 437–442 (2023).

He, G.-C. et al. Photo-induced catalytic C−H heteroarylation of group 8 metallocenes. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100768 (2022).

He, G.-C. et al. Visible-light-induced catalytic construction of tricyclic aza-arenes from halopyridines. Chem. Catal. 3, 100793 (2023).

Jeffrey, J. L., Petronijević, F. R. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Selective radical–radical cross-couplings: Design of a formal β-mannich reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 8404–8407 (2015).

Garza-Sanchez, R. A., Patra, T., Tlahuext-Aca, A., Strieth-Kalthoff, F. & Glorius, F. DMSO as a switchable alkylating agent in heteroarene C−H functionalization. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 10064–10068 (2018).

Li, J., Huang, C.-Y., Han, J.-T. & Li, C.-J. Development of a quinolinium/cobaloxime dual photocatalytic system for oxidative C–C cross-couplings via H2 release. ACS Catal. 11, 14148–14158 (2021).

Constantin, T. et al. Aminoalkyl radicals as halogen-atom transfer agents for activation of alkyl and aryl halides. Science 367, 1021–1026 (2020).

Juliá, F., Constantin, T. & Leonori, D. Applications of halogen-atom transfer (XAT) for the generation of carbon radicals in synthetic photochemistry and photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 122, 2292–2352 (2022).

Lowry, M. S. et al. Single-layer electroluminescent devices and photoinduced hydrogen production from an ionic iridium(iii) complex. Chem. Mater. 17, 5712–5719 (2005).

Bryden, M. A. et al. Lessons learnt in photocatalysis–the influence of solvent polarity and the photostability of the photocatalyst. Chem. Sci. 15, 3741–3757 (2024).

Wayner, D. D. M. & Houmam, A. Redox properties of free radicals. Acta Chem. Scand. 52, 377–384 (1998).

Popov, K. K. et al. Reductive amination revisited: Reduction of aldimines with trichlorosilane catalyzed by dimethylformamide─functional group tolerance, scope, and limitations. J. Org. Chem. 87, 920–943 (2022).

Woo, J. et al. Scaffold hopping by net photochemical carbon deletion of azaarenes. Science 376, 527–532 (2022).

Hu, C. et al. Uncanonical semireduction of quinolines and isoquinolines via regioselective HAT-promoted hydrosilylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 25–31 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22301299 and 22271277), the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP I202423), and the Doctoral Research Startup Fund Project of Liaoning Province (2020BS017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.-A. C. conceived and supervised the project. Q.-A. C., and S.-Y. G. designed the experiments. S.-Y. G., Y.-P. L., J.-S. H., L.-B. H., G.-C. H., D.-W. J., and B.-S. W. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, SY., Liu, YP., Huang, JS. et al. Visible light-induced chemoselective 1,2-diheteroarylation of alkenes. Nat Commun 15, 6102 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50460-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50460-4

- Springer Nature Limited