Abstract

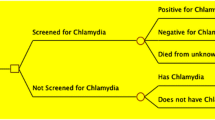

We proposed a mixed-integer program to model the management of C. trachomatis infections in women visiting publicly funded family planning clinics. We intended to maximize the number of infected women cured of C. trachomatis infections. The model incorporated screening, re-screening, and treatment options for three age groups with respective age-specific C. trachomatis infection and re-infection rates, two possible test assays, and two possible treatments. Our results showed the total budget had a great impact on the optimal strategy incorporating screening coverage, test selection, and treatment. At any budget level, the strategy that used a relatively small per-patient budget increase to re-screen all women who tested positive 6 months earlier always resulted in curing more infected women and more cost-saving than the strategy that was optimal under the condition of not including a re-screening option.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2001 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 2002).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, MMWR 51 (No. RR-6) (2002) 32–36.

S.L. Groseclose, A.A. Zaidi, S.J. DeLisle, W.C. Levine and M.E. St Louis, Estimated incidence and prevalence of genital chlamydia trachomatis infections in the United States, 1996, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 26 (1999) 339–344.

K.J. Mertz, R.A. Voigt, K. Hutchins and W.C. Levine, Jail STD Prevalence Monitoring Group, Findings from STD screening of adolescents and adults entering corrections facilities, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 29 (2002) 834–839.

T.A. Farley, D.A. Cohen and W. Elkins, Asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases: The case for mass screening, American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36 (2003) 502–509.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Guideline for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, MMWR 47 (RR-1) (1998) 53–59.

D. Rein, W. Kassler, K. Irwin and L. Rablee, Direct medical cost of pelvic inflammatory disease and its sequelae: Decreasing, but still substantial, Obstetrics and Gynecology 95 (2000) 397–402.

American Social Health Association, Update on fiscal year 1994: Funding for the STD program of the CDC and NIH, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 21 (1994) 55–58.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Screening tests to detect Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections-2002, MMWR 52 (No. RR-15) (2002) 9–10, 37.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Screening for chlamydial infection: Recommendations and rationale, American Journal of Preventive Medicine 20 (2001) 90–94.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Gonorrhea and chlamydial infections, Technical bulletin no. 190 (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Washington, 1994).

American Academy of Pediatrics, Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (American Academy of Pediatrics, Elk Grove Village, 1994).

American Medical Association, AMA Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS): Recommendations and Rationale (American Medical Association, Chicago, 1994).

J.M. Marrazzo, C.L. Celum, S.D. Hillis, D. Fine, S. Delisle and H.H. Handsfield, Performance and cost-effectiveness of selective screening criteria for Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 24 (1997) 131–141.

G. Tao, T. Gift, C. Walsh, K. Irwin and W. Kassler, Optimal resource allocation for curing chlamydia trachomatis infection among asymptomatic women of clinics operating on a fixed budget, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 29 (2002) 703–709.

P. Nathanson, M. Sammel and M. Berlin, Repeat chlamydia infections in region III family planning clinics-implications for screening programs, Presented at the 2002 National STD Prevention Conference, San Diego, March 4-7. Abstract #B5F.

F. Xu, J.A. Schillinger, L.E. Markowitz, M.R. Sternberg, M.R. Aubin and M.E. St Louis, Repeat Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women: Analysis through a surveillance case registry in Washington state, 1993-1998, American Journal of Epidemiology 152 (2000) 1164–1170.

F. Hillier and G. Lieberman, Introduction to Operations Research (McGraw-Hill Inc., New York, 1995).

S.H. Jacobson, E.C. Sewell, R. Deuson and B.G. Weniger, An integer programming model for vaccine procurement and delivery for childhood immunization: A pilot study, Health Care Management Science 2 (1999) 1–9.

A. Richter, M.L. Brandeau and D.K. Owens, An analysis of optimal resource allocation for prevention of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in injection drug users and non-users, Medical Decision Making 19 (1999) 167–179.

P. Taylor and S. Huxley, A break from tradition for the San Francisco police: Patrol officer scheduling using an optimization-based decision support system, Interfaces 19 (1989) 4–24.

L.W. Dicker, D.J. Mosure, W.C. Levine, C.M. Black and S.M. Berman, Impact of switching laboratory tests on reported trends in Chlamydia trachomatis infections, American Journal Epidemiology 151 (2000) 430–435.

W. Whittington, C. Kent, P. Kissinger et al., Determinants of persistent and recurrent Chlamydia trachomatis infection in young women, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 28 (2001) 117–123.

M.R. Howell, T.C. Quinn, W. Brathwaite and C.A. Gaydos, Screening women for Chlamydia trachomatis in family planning clinics: The cost effectiveness of DNA amplification assays, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 25 (1998) 108–117.

R. Steece, National Pricing of Chlamydia Reagents (Association of State and Territorial Public Health Laboratory Directors, Washington, 1997).

D. Dean, D. Ferrero and M. McCarthy, Comparison of performance and cost-effectiveness of direct fluorescent-antibody, ligase chain reaction, and PCR assays for verification of chlamydial enzyme immunoassay results for populations with a low to moderate prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection, Journal of Clinical Microbiology 36 (1998) 94–99.

A.C. Haddix, S.D. Hillis and W.J. Kassler, The cost effectiveness of azithromycin for Chlamydia trachomatis infections in women, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 22 (1995) 274–280.

S.D. Hillis, F.B. Coles, B. Litchfield et al., Doxycycline and azithromycin for prevention of chlamydial persistence or recurrence one month following treatment in women: A use-effectiveness study in public health settings, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 25 (1997) 5–11.

A. Cerin, L. Grillner and E. Persson, Chlamydia test monitoring during therapy, International Journal of STD & AIDS 2 (1991) S176–S179.

D.H. Martin, T.F. Mroczkowski, Z.A. Dalu et al., A controlled trial of a single dose of azithromycin for the treatment of chlamydial urethritis and cervicitis, New England Journal of Medicine 327 (1992) 921–925.

H.H. Handsfield and W.E. Stamm, Treating chlamydia infection: Compliance versus cost, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 25 (1997) 12–13.

Anonymous, Drug Topics Red Book (Medical Economics Company, Inc., Montvale, 1998).

M.B. Shafer, R.H. Pantell and J. Schachter, Is the routine pelvic examination needed with the advent of urine-based screening for sexually transmitted diseases? Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 153 (1999) 119–125.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Recommendations for the prevention and management of Chlamydia trachomatis infections, MMWR 42 (RR-12) (1993) 2–3.

J.T. Humphreys, J.F. Henneberry, R.S. Rickard and J.L. Beebe, Costbenefit analysis of selective screening criteria for Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women attending Colorado family planning clinics, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 19 (1992) 47–53.

D.J. Mosure, S. Berman, D. Fine, S. Delisle, W. Cates and J.R. Boring, Genital chlamydia infections in sexually active female adolescents: Do we really need to screen everyone? J. Adolesc Health 20 (1997) 6–13.

C.A. Gaydos, M.R. Howell, B. Pare, K.L. Clark, D.A. Ellis, R.M. Hendrix et al., Chlamydia trachomatis infections in female military recruits, New England Journal of Medicine 339 (1998) 739–744.

H.S. Weinstock, G.A. Bolan, R. Kohn, C. Balladares, A. Back and G. Oliva, Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women: A need for universal screening in high prevalence population? American Journal Epidemiology 135 (1992) 41–47.

C. Eubanks, W.E. Lafferty, A. Kimball, R. MacCormack and W.J. Kassler, Privatization of STD services in Tacoma,Washington: A quality review, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 26 (1999) 537–542.

S.S. Bull, C. Rietmeijer, J.D. Fortenberry et al., Practice patterns for the elicitation of sexual history, education and counseling among providers of STD services: Results from the Gonorrhea Community Action Project (GCAP), Sexually Transmitted Diseases 26 (1999) 584–589.

G. Tao, K.L. Irwin and W.J. Kassler, Missed opportunities to assess sexually transmitted diseases among US adults during routine medical check-ups: Results of the 1994 US National Health Interview Survey, American Journal of Preventive Medicine 18 (2000) 109–114.

J.R. Schwebke, R. Sadler, J.M. Sutton and E.W. Hook III, Positive screening tests for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection fail to lead consistently to treatment of patients attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 24 (1997) 181–184.

L. Westrom and D. Eschenbach, Pelvic inflammatory disease, in: Sexually Transmitted Diseases, eds. K.K. Holmes, P.F. Sparling, P.-A. Mardh et al. (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1999).

S.D. Hillis, B.S. Owens, P.A. Marchbanks, L.E. Amsterdam and W.R. Mac Kenzie, Recurrent chlamydial infections increase the risks of hospitalization for ectopic pregnancy and pelvic inflammatory disease, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 176 (1997) 103–107.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tao, G., Abban, B.K., Gift, T.L. et al. Applying a Mixed-Integer Program to Model Re-Screening Women who Test Positive for C. trachomatis Infection. Health Care Management Science 7, 135–144 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HCMS.0000020653.31862.23

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HCMS.0000020653.31862.23