Abstract

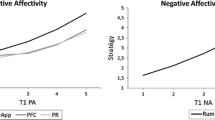

This study investigates the impact of subjective changes in the execution of the roles of spouse, worker, and parent on the level and structure of positive and negative affect. According to the self-theory of subjective change, perceived improvement and decline are unsettling because each violate standards of self-conception, but perceived stability satisfies the organismic desire for homeostasis. Therefore individuals who perceive more changes in themselves should report more negative and less positive affect, compared with individuals who feel they have remained the same. The context-dependence theory of affects also argues that the correlation of negative and positive affect is strong when individuals are distressed and modest when they are in homeostasis. Thus, the correlation of positive and negative should approach unity as individuals perceive more change in themselves. Data are from the MIDUS study and sample (N = 3,032) of adults between the ages of 25 and 74. Respondents completed scales of positive and negative affect, and evaluated their current and past (10 years ago) functioning as spouses (or close relationship), in work, and as parents (relationship with their children). The correlation of positive and negative affect approached unity at the highest levels of perceived improvement, r = −.93, and at the highest levels of perceived decline, r = −.90, but was modestly correlated at no change, r = −.52. Moreover, the level of positive affect was lower, and negative affect was higher, among adults who perceived more improvement as well as declines, compared with adults who remained the same. Implications for the study of objective life events as well as health interventions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Albert, S. (1977). Temporal comparison theory. Psychological Review, 84(6), 485-503.

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being. New York: Plenum.

Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Brown, J. D., & McGill, K. L. (1989) The cost of good fortune: When positive life events produce negative health consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1103-1110.

Burke, P. J. (1991). Identity processes and social stress. American Sociological Review, 56, 836-849.

Burke, P. J. (1996). Social identities and psychosocial stress. In H. B. Kaplan (Ed.), Psychosocial stress: Perspectives on structure, theory, life-course, and methods (pp. 141-174). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Burke, P. J., & Cast, A. D. (1998). Stability and change in the gender identities of newly married couples. Social Psychology Quarterly, 60(4), 277-290.

Diener, E. (1993). Assessing subjective well-being: Progress and opportunities. Social Indicators Research, 31, 103-157.

Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1105-1117.

Diener, E., Larson, R. J., Levine, S., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). Intensity and frequency: Dimensions underlying positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1253-1265.

Diener, E., Sandvik, E., & Pavot, W. (1991). Happiness is the frequency, not the intensity, of positive versus negative affect. In F. Strack, M. Argyle, & N. Schwartz (Eds.), Subjective well-being: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 119-139). Elmsford NY: Pergamon.

Foote, N. N. (1951). Identification as the basis for a theory of motivation. American Sociological Review, 26, 14-21.

Gecas, V., & Burke, P. J. (1995). Self and identity. In K. S. Cook, G. A. Fine, & J. S. House (Eds.), Sociological perspectives on social psychology (pp. 41-67). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Green, D. P., Goldman, S. L., & Salovey, P. (1993). Measurement error masks bipolarity in affect ratings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 1029-1041.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213-218.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York: Free Press.

Jones, S. C. (1973). Self-and interpersonal evaluations: Esteem theories versus consistency theories. Psychological Bulletin, 79(3), 185-199.

Keyes, C. L. M., & Lopez, S. J. (in press). Toward a science of mental health: Positive directions in diagnosis and interventions. In C. R. Snyder& S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Keyes, C. L. M., & Ryff, C. D. (1999). Psychological well-being in midlife. In S. L. Willis & J. D. Reid (Eds.), Middle aging: Development in the third quarter of life (pp. 161-180). Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Keyes, C. L. M., & Ryff, C. D. (2000). Subjective change and mental health: A self-concept theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 264-279.

Kiecolt, K. J. (1994). Stress and the decision to change oneself: A theoretical model. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 49-63.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Lecky, P. (1945). Self-consistency: A theory of personality. New York: Island Press.

MacKinnon, N. J. (1994). Symbolic interactionism as affect control. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Markus, H. R., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41, 954-969.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Miller, M. A., & Rahe, R. H. (1997). Life changes scaling for the 1990s. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 43(3), 279-292.

Mroczek, D. K., & Kolarz, C. M. (1998). The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(5), 1333-1349.

Pearlin, L. I., Lieberman, M. A., Menaghan, E. G., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337-356.

Robinson, D. T., & Smith-Lovin, L. (1992). Selective interaction as a strategy for identity maintenance: An affect control model. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(1), 12-28.

Rosenberg, M. (1981). The self-concept: Social product and social force. In M. Rosenberg & R. H. Turner (Eds.), Social psychology: Sociological perspectives (pp. 593-624). New York: Basic Books.

Rosenberg, M. (1990). Reflexivity and emotions. Social Psychology Quarterly, 53(1), 3-12.

Ross, M., & Conway, M. (1986). Remembering one's own past: The construction of personal histories. In R. M. Sorrentino & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior (pp. 122-144). Chichester, England: Wiley.

Ross, M., Eyman, A., & Kishchuck, N. (1986). Determinants of subjective well-being. In J. M. Olson, C. P. Herman, & M. Zanna (Eds.), Relative deprivation and social comparison (pp. 79-93). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Russell, J. A., & Carroll, J. M. (1999). On the bipolarity of positive and negative affect. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 3-30.

Sedikides, C., & Strube, M. J. (1997). Self-evaluation: To thine own self be good, to thine own self be sure, to thine own self be true, and to thine own self be better. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 209-269) San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. San Francisco, CA: Freeman.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1991). Learned optimism. New York: Knopf.

Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Lynch, M. (1993). Self-image resilience and dissonance: The role of affirmational resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64(6), 885-896.

Swann, W. B., Jr. (1990). To be adored or to be known? The interplay of self-enhancement and self-verification. In E. T. Higgins & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition, (Vol. 2, pp. 408-448). New York: Guilford.

Swann, W. B., Jr., & Brown, J. D. (1990). From self to health: self-verification and identity disruption. In B. R. Sarason, I. G. Sarason, & G. R. Pierce (Eds.), Social support: An interactional view (pp. 150-172). New York: Wiley.

Swann, W. B., Jr., Griffin, J. J., Jr., Predmore, S. C., & Gaines, B. (1987). The cognitive-affective crossfire: When self-consistency confronts self-enhancement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(5), 881-889.

Swann, W. B., Jr., & Hill, C. (1982). When our identities are mistaken: Reaffirming self-conceptions through social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 59-66.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusions and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 193-210.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1994). Positive illusions and well-being revisited: Separating fact from fiction. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 21-27.

Taylor, S. E., Neter, E., & Wayment, H. A. (1995). Self-evaluation processes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(12), 1278-1287.

Thoits, P. A. (1983). Dimensions of life events that influence psychological distress: An evaluation and synthesis of the literature. In H. B. Kaplan (Ed.), Psychosocial Stress: Trends in theory and research (pp. 33-103). New York: Academic press.

Thoits, P. A. (1994). Stressors and problem solving: The individual as psychological activist. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 143-159.

Thoits, P. A. (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior (extra issue), 53-79.

Turner, R. J., & Avison, W. R. (1992). Innovations in the measurement of life stress: Crisis theory and the significance of event resolution. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 36-50.

Turner, R. J., Wheaton, B., & Lloyd, D. A. (1995). The epidemiology of social stress. American Sociological Review, 60, 104-125.

Watson, D., & Tellegen, A. (1985). Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 219-235.

Wethington, E., Cooper, H., & Holmes, C. S. (1997). Turning points in midlife. In I. H. Gotlib & B. Wheaton (Eds.), Stress and adversity over the life course: Trajectories and turning points (pp. 215-231). London: Cambridge University Press.

Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist, 35(2), 151-175.

Zajonc, R. B. (1984). On the primacy of affect. American Psychologist, 39(2), 117-123.

Zautra, A. J., Potter, P. T., & Reich, J. W. (1997). The independence of affects is context-dependent: An integrative model of the relationship of positive and negative affect. In K. W. Schaie & M. P. Lawton (Eds.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (Vol. 17, pp. 75-103). New York: Springer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

an affiliated program of Emory University

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keyes, C.L.M. Subjective Change and Its Consequences for Emotional Well-Being. Motivation and Emotion 24, 67–84 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005659114155

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005659114155