Abstract

Purpose

To develop physician recommendations for communicating with families during pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in Canada and the USA.

Methods

We used the Delphi methodology, which consists of 3 iterative rounds. During Round 1, we conducted semi-structured interviews with each panelist, who were pediatricians from the USA and Canada from the following pediatric specialties: intensive care, cardiac intensive care, and neonatology. We then used content analysis to code the interviews and develop potential recommendations. During Round 2, panelists evaluated each item via a Likert scale as a potential recommendation. Before Round 3, panelists were provided personalized feedback reports of the results of Round 2. During Round 3, panelists re-evaluated items that did not reach consensus during Round 2. Items that reached consensus in Rounds 2 and 3 were translated into the final framework.

Results

Consensus was defined as (1) a median rating ≥ 7 and (2) ≥ 70% of the panelists rating the recommendation ≥ 7. The final framework included 105 recommendations. The recommendations emphasized the importance of clarifying the goal of ECMO, its time-limited nature, and the possibility of its discontinuation resulting in patient death. The recommendations also provide guidance on how to share updates with the family and perform compassionate discontinuation.

Conclusion

A panel of experts from Canada and the USA developed recommendations for communicating with families during pediatric ECMO therapy. The recommendations offer guidance for communicating during the introduction of ECMO, providing updates throughout the ECMO course, and during the discontinuation of ECMO. There are also points of disagreement on best communication practices which should be further explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is a complex medical intervention that is increasingly being used by the pediatric population [1]. It is associated with significant morbidities and ongoing high mortality. ECMO therapy involves multiple ethical dilemmas and is associated with greater moral distress than routine intensive care [2,3,4,5,6], including significant parental psychological distress [7,8,9]. Communication during ECMO courses is often unclear, with one study reporting that nearly a quarter of parents felt they were not told about the possibility of death until their child failed to improve on ECMO and discontinuation was discussed [8]. High-quality communication is crucial to the support that clinical teams can provide families [8,9,10].

Despite the widespread endorsement of family-centered care and the known importance of quality communication in the ICU setting, a recent review found no practical guidelines for communicating with families during pediatric ECMO therapy [11,12,13,14,15]. While there have since been a few narrative reviews based on general palliative care principles on communication during ECMO and compassionate discontinuation, no consensus guide for either exists [16,17,18,19]. Additionally, the two existent guides for communicating during ECMO focus on conversations surrounding initiation and discontinuation, but do not provide in-depth practical guidance on providing families with updates throughout the ECMO course (beyond checking for prognostic awareness) [17, 18]. Lastly, no study has identified areas of disagreement amongst pediatric intensivists about best communication practices during pediatric ECMO therapy. The aim of our study was to address these gaps in the literature.

Methods

Study design

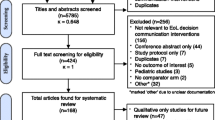

We conducted a Delphi study between April 2021 and March 2022. The Delphi method is a consensus-building methodology that uses iterative rounds of questionnaires, anonymous item ratings, incorporation of panelist feedback between rounds, and feedback reports to inform panelists how their ratings compare to the overall panel ratings and share the panel’s anonymized comments (Fig. 1) [20, 21].

The present study has been approved according to the ethical review process of the medical faculty of the University of Zurich. Informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Expert panel

The Delphi methodology requires the panelists to have expertise on the topic at hand. Our inclusion criteria included that the panelist has the following: (1) managed > 50 pediatric ECMO runs, (2) published ≥ 1 article on pediatric ECMO (most panelists have also published on ethics or communication), and (3) a reputation as a good bedside communicator as judged from the feedback of colleagues, trainees, and former trainees. All invited potential panelists practice in the USA or Canada. During the selection of panelists, consideration was given to ensure regional geographic and subspecialty diversity. Potential candidates were invited to participate via e-mail.

Data collection

Round 1

In Round 1, one researcher (SE) conducted semi-structured, open-ended interviews with individual panelists via an online video conferencing platform to explore perspectives on communicating with families during pediatric ECMO therapy. The same author (SE) transcribed the interviews and entered them into NVivo [22]. The anonymized interviews were coded using content analysis by one researcher (SE), and 20% of the interviews were double-coded by a second researcher (JS) and checked for agreement. All disagreements were discussed and resolved. All potential recommendations were reviewed and discussed by 3 researchers (SE, JS, RK), and all disagreements were resolved.

Round 2

In Round 2, panelists evaluated items generated from Round 1 via an online questionnaire. Panelists evaluated each item via a Likert scale (Strongly Disagree (1), Strongly Agree (9)) as a potential recommendation for communicating with families during pediatric ECMO therapy. Panelists also had the option to provide written comments for each item.

Round 3

Before Round 3, panelists were provided with personalized feedback reports of the results of Round 2. The reports included the following for each item: the panelist’s previous response, a boxplot depicting the median and IQR of the panel’s ratings, and a summary of the anonymized comments. Items that did not reach consensus during Round 2 were redistributed during Round 3 for re-evaluation. The Round 3 questionnaire included the feedback report data beneath each item so that panelists could easily compare their previous rating to the aggregate panel’s rating and review the panel’s comments.

Data analysis

We analyzed the data to assess panel consensus for each item as a recommendation for communicating with families during pediatric ECMO therapy. Items were considered to have achieved consensus if: (1) the median rating was ≥ 7 and (2) ≥ 70% of the panelists rated the recommendation ≥ 7. We defined the criteria for consensus a priori and used the most frequently cited criteria for consensus in the Delphi literature [23]. We also assessed for areas of disagreement, which we defined as at least half of the panel scoring the item outside of a single 3-point range on the Likert scale (i.e., more than 50% of scores were at least 4 points apart). This criterion for disagreement has been used in prior Delphi literature [24].

Results

The panel consisted of 11 pediatricians from the USA (8) and Canada (3). Thirteen pediatricians were invited to participate; 1 did not respond and 1 declined. This sample size falls within the recommended range for a Delphi with a homogenous panel (e.g., critical care pediatricians) [25]. The panel was comprised of the following pediatric specialists: intensivists (5), cardiac intensivists (5), neonatologists (1). All three rounds had a 100% completion rate.

In Round 1, 11 interviews were conducted which generated 142 recommendations. Based on themes identified during Round 1, recommendations were grouped by phases of the ECMO course: Initiation of ECMO, Continuation of ECMO, and Discontinuation of ECMO. Discontinuation of ECMO was further divided into Discontinuation with an expected good outcome, Discontinuation with an uncertain outcome, and Discontinuation with expected death. There was also a small concluding section on supportive services for families.

In Round 2, 114 recommendations reached consensus, 18 recommendations did not. Ten recommendations were removed due to redundancy, poor wording, or lack of generalizability.

Recommendations not reaching consensus in Round 2 were re-evaluated in Round 3, and 5 reached consensus. Three recommendations were removed for being redundant or a general EOL practice not specific to ECMO. During the translation of results into the final framework, some items were combined or slightly reworded. This resulted in a final framework of 105 recommendations: Initiation (16), Continuation (36), Discontinuation with an expected good outcome (6), Discontinuation with an uncertain outcome (11), Discontinuation with expected death (29), and Supportive services (7).

Initiation of ECMO

The recommendations for this phase emphasized the importance of conveying the seriousness of the child’s illness and their prognosis while allowing the family to maintain hope (Table 1). It was recommended to discuss the goal of ECMO and clarify that ECMO does not treat the child’s underlying illness and is offered as a time-limited trial that may be discontinued if the previously discussed goals are not met or a major complication occurs.

The recommendations suggest that when time permits (e.g., prenatal diagnosis or chronic condition), the physician should discuss ECMO and the possibility of it being part of the patient’s future treatment plan early. It was recommended to elicit the family’s values, goals, and preferences (VGPs) to determine whether the burden of support during ECMO and the potential negative impact to quality of life (QOL) after ECMO are consistent with their preferences.

Continuation of ECMO

Some of the recommendations in this phase are also in the initiation phase, as panelists reported these items required repetition. The recommendations for this phase emphasized personalizing care, such as determining if the family desires any additional stakeholders to be involved in decision-making (e.g., grandparents), exploring the family’s information preferences (e.g., big picture vs. details), and discussing the possible clinical outcomes in the context of the family’s VGPs (Table 2).

The recommendations also focused on how to discuss the patient’s path on ECMO. It was recommended to emphasize that the pathway on ECMO is often not straightforward (fluctuating days of progression or regression) and that the clinical goals may change during the course of therapy. Recommendations included discussion of the regular reassessment for the appropriateness of ongoing ECMO, while assuring transparency, and timely updates (daily) on progress and prognosis.

Discontinuation with an expected good outcome

These recommendations focused on assuring families that the child is ready to discontinue ECMO (Supplemental Table 1). To do this, it was recommended to explain why a good outcome is expected, and if the family is concerned about discontinuation, to explain that the goals of ECMO have been met and that staying on longer could result in a complication.

Discontinuation with an uncertain outcome

Discontinuation with an uncertain outcome was defined as discontinuation of ECMO (e.g., due to a complication, no further benefit expected) where the patient may survive with other ongoing ICU therapies. Recommendations refer back to earlier discussions about benefit-burden ratio of ECMO, and emphasize the importance of clear communication and acknowledgement of uncertainty (Table 3). It was recommended to discuss the potential outcomes in terms of the family’s VGPs to help inform decision-making. The recommendations also focused on discussions about escalation. It was recommended to discuss limitations of escalation (e.g., CPR), assess if the family would want to re-initiate ECMO (if medically indicated and technically feasible), and discuss what other supports and treatments would be provided within limitations set on escalation.

Discontinuation with expected death

The recommendations for this phase focused on explaining why ECMO must be discontinued (Table 4). It was recommended to introduce the need to discontinue as new information (e.g., complication, failing kidneys), discuss that ECMO is no longer achieving the previously defined goals, and explain that ECMO is no longer helping the patient but rather is prolonging the dying process. Another focus of the recommendations was the importance of providing a unified and clear recommendation to discontinue ECMO that incorporates the family’s VGPs.

It was recommended to personalize the discontinuation process around the family’s preferences and address their hopes and fears for their child’s death. Practical recommendations for compassionate discontinuation were made including the following: to offer to remove the endotracheal tube to facilitate viewing the child’s face, to cut or clamp the circuit (vs. surgical decannulation), and to allow the family to hold their child during the process if they desire.

Support services

It was recommended that all families of children on ECMO be offered supportive services: (1) social worker, (2) palliative care team consult, (3) chaplaincy services, (4) psychological counselling, (5) interpreter for limited English proficiency, (6) Child Life services (including for patient siblings), and (7) bereavement services (when appropriate).

Areas of disagreement

Several areas of disagreement were identified (Supplemental Table 2). During the continuation phase of ECMO, panelists disagreed on whether updates should include a comparison of how the child is doing on ECMO compared to other children with a similar diagnosis. Some panelists opined strongly against this, while others reported doing this routinely and find it helpful in ensuring family understanding of their child’s prognosis. Panelists also disagreed on several aspects about continuity of care during the continuation phase. For example, they disagreed on whether the primary intensivist should hold weekly meetings to update the family. While panelists reported they often do this, they noted it should be tailored to the family’s preference for receiving updates. During the phase of discontinuation with an expected good or uncertain outcome, panelists disagreed on whether parents should be asked if they would want to go back on ECMO (if needed and possible). Some panelists reported that families’ input should be solicited and considered, but that this is largely a clinical decision and the family should not be made to feel responsible for the decision. During the discontinuation phase for an uncertain outcome or expected death, panelists disagreed on whether a multidisciplinary family care conference should be used to deliver the news. Many panelists reported this was helpful, to ensure the family that the team is all in agreement, and to answer their questions, but some panelists reported that this method can overwhelm families and separates them from their child, so the delivery of the news should be tailored to the parent’s preferences, which may be at the bedside or with just with the clinician with whom they have the strongest relationship. Lastly, while this item reached consensus, there was disagreement on whether cut/clamp should always be the recommended procedure for compassionate decannulation (vs surgical decannulation). Some panelists reported it simply depends on the clinical situation, while others noted it should depend on the family’s preferences.

Discussion

This study sought to establish a consensus guideline for physician communication with families during pediatric ECMO therapy in an effort to optimize best practices. This study demonstrates a stepwise approach to communicating with families during the phases of initiation, continuation, and discontinuation of ECMO. To date, only narrative review articles (based on general EOL practices) have offered guidance for communicating with families during pediatric ECMO therapy. We offer a broader-based consensus guideline to support providers in communication during pediatric ECMO.

Our study emphasizes the need to provide full information about ECMO and careful counselling on expected potential outcomes. The possibility of ECMO being unsuccessful and needing to be discontinued despite expected patient death should be discussed with the family before ECMO is initiated and discussed again during the course of therapy. This was considered foundational to a series of conversations about benefits, harms, expectations, and progress (or lack thereof) during ECMO support. This is consistent with established communication practices which advise early discussion of the potential for both successful and unsuccessful treatment outcomes [17, 26]. Preparatory guidance can be helpful in grounding future discussions to reset expectations should ECMO be predicted to be unsuccessful.

Our guideline shared many consistencies with existing communication recommendations for pediatric ECMO therapy. In particular, our suggestions were consistent with others in emphasizing the time-limited nature of ECMO, that ECMO is not a treatment, the risk of serious complications and their potential impact on the child’s QOL, and the need for clinicians to provide a clear recommendation to discontinue ECMO that is aligned with the family’s values [15,16,17,18,19]. However, it should be noted that while all existing communication guides recommend discussing the time-limited and trial nature of ECMO, recent literature has questioned the appropriateness of discontinuing ECMO in patients with capacity who refuse; this may alter the nature of such conversations in select patients [27].

Unlike the two existing guides for communication during pediatric ECMO, our guideline provides in-depth practical recommendations for providing families with updates throughout the ECMO course. We believe these guidelines are additive to the literature since quality updates help cultivate prognostic awareness for the family. Our guideline’s recommended practices of compassionate discontinuation are consistent with the current literature, including personalizing the discontinuation process, preparing families for what to expect, optimizing symptom management, and recommending cutting or clamping over surgical decannulation in most cases [16, 18, 19].

Discussions of family VGPs are an expected and recommended best practice in the current era [24, 28,29,30]. Our panelists emphasized the importance of framing discussions in the context of family VGPs as one would expect and is recommended in every pediatric ECMO communication guideline [15,16,17,18]. However, additional work is needed to provide guidance on how to clarify the family’s VGPs effectively for use in framing conversations about the patient’s trajectory and treatment options.

Our study is the first to assess areas of disagreement amongst pediatric intensivists about communication practices during pediatric ECMO therapy. These areas, including providing comparisons to other children with similar diagnosis, apply to general pediatric intensive care and warrant further exploration as no clear answers on best practices exist in the literature. Another point of disagreement, whether recommending the cut or clamp method (vs surgical) for compassionate decannulation is always warranted, is an important area of disagreement as the only two other papers on compassionate decannulation recommend the cut/clamp method, though one paper notes that families may have different preferences that influence the method used [16, 19]. It is important to note that this item reached consensus in our study, but the panelists’ comments indicated that the dispersion of its ratings was likely because some panelists felt that the recommended method of decannulation should be tailored to the family’s preferences and the clinical situation, thus making a universal recommendation for the cut/clamp method as the preferred method for compassionate decannulation potentially inappropriate.

This study’s main strength is that it generated a consensus guideline including experts from 11 centers, using a rigorous methodology [20]. However, one limitation is that while there were objective criteria to assess the expertise of panelists, the criteria for panelists’ communication skills were subjective and could be met by many experts. However, during panel selection, additional consideration was given to ensure subspecialty and geographic diversity. Consequently, there were surely potential panelists who were not included despite excellent communication skills and ECMO expertise. Panelists were only recruited from the USA and Canada, so further research is needed to assess the generalizability of these recommendations to other countries and patient populations. Additionally, panelists reported limited experience in collaborating with children directly (since many are unconscious) and therefore could not generate advice for communicating with patients. Since collaborating with children during their care is of critical importance, how best to do so during ECMO therapy should be studied further [24, 31, 32]. Another limitation of this study is that it presents recommendations only from the physician perspective and lacks the additional lenses of other bedside ECMO providers. Finally, and of key importance, our study did not include the perspective of families, which would be deeply important to augmenting and strengthening this guidance. Family and patient perspectives that represent a wide range of experience, and are inclusive of a wide diversity of groups, including those with language barriers and who self-identify in marginalized groups are integral to determining best practices. Future study should incorporate and validate this work from the patient and family lens. However, this guideline provides a foundational reference for clinicians on how best to communicate with families during pediatric ECMO, and the grounds of future studies to enhance best practices.

Conclusion

To date, there is no established consensus guideline for communicating with families during pediatric ECMO therapy. As such, we carried out a Delphi study utilizing experts from 11 institutions to develop the first consensus guideline for best practices, including the first to provide in-depth practical guidance on sharing updates with the family throughout the ECMO course. Furthermore, we identified key areas of disagreement about best communication practices that should be further explored. This guideline can contribute to enhancing ECMO practices and serve as a nidus of future research including exploring patient and family perspectives on communication during pediatric ECMO therapy.

Availability of data and materials

All data is de-identified and available for review upon request.

References

Barbaro RP, Paden ML, Guner YS et al (2017) ELSO Member Centers. Pediatric extracorporeal life support organization registry international report 2016. ASAIO J 63:456–463. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAT.0000000000000603

Carlisle EM, Loeff DS (2020) Emerging issues in the ethical utilization of pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Curr Opin Pediatr 32(3):411–415. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000901

Clark JD, Baden HP, Berkman ER, Bourget E, Brogan TV, Di Gennaro JL, Doorenbos AZ, McMullan DM, Roberts JS, Turnbull JM, Wilfond BS, Lewis-Newby M (2022) Seattle Ethics in ECLS (SEE) Consortium. Ethical considerations in ever-expanding utilization of ECLS: a research agenda. Front Pediatr 10:896232. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.896232

Mavroudis C, Mavroudis CD, Green J, Sade RM, Jacobs JP, Kodish E (2012) Ethical considerations for post-cardiotomy extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Cardiol Young 22(6):780–786. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951112001540

Truog RD, Thiagarajan RR, Harrison CH (2015) Ethical dilemmas with the use of ECMO as a bridge to transplantation. Lancet Respir Med 3(8):597–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00233-7

Emple A, Fonseca L, Nakagawa S, Guevara G, Russell C, Hua M (2021) Moral distress in clinicians caring for critically ill patients who require mechanical circulatory support. Am J Crit Care 30(5):356–362. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2021777

Lewis AR, Wray J, O’Callaghan M et al (2014) Parental symptoms of posttraumatic stress after pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med 15:e80–e88. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000000036

Curley MAQ, Meyer EC (2003) Parental experience of highly technical therapy: survivors and nonsurvivors of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Pediatr Crit Care Med 4:214–219. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PCC.0000043915.79848.8D

Epps S, Nowak TA (1998) Parental perception of neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Children’s Health Care 27:215–230. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000435674.83682.96

Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S et al (2002) Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 156:14–19. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.156.1.14

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2003; 112:691–697.

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001.

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC et al (2017) Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med 45(1):103–128. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169

Labrie NHM, van Veenendaal NR, Ludolph RA, Ket JCF, van der Schoor SRD, van Kempen AAMW (2021) Effects of parent-provider communication during infant hospitalization in the NICU on parents: a systematic review with meta-synthesis and narrative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns 104(7):1526–1552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.04.023

Moynihan KM, Dorste A, Siegel BD, Rabinowitz EJ, McReynolds A, October TW (2021) Decision-making, ethics, and end-of-life care in pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a comprehensive narrative review. Pediatr Crit Care Med 22(9):806–812. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002766

Kirsch R, Munson D (2018) Ethical and end of life considerations for neonates requiring ECMO support. Semin Perinatol 42(2):129–137. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2017.12.009

Moynihan KM, Purol N, Alexander PMA, Wolfe J, October TW (2021) A communication guide for pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med 22(9):832–841. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002758

Joong A, Derrington SF, Patel A et al (2019) Providing compassionate end of life care in the setting of mechanical circulatory support. Curr Pediatr Rep 7:168–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40124-019-00206-4

Machado DS, Garros D, Montuno L, Avery LK, Kittelson S, Peek G, Moynihan KM (2022) Finishing well: compassionate extracorporeal membrane oxygenation discontinuation. J Pain Symptom Manage 63(5):e553–e562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.11.010

Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C (2011) Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 6:e20476. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020476

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H: The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020) NVivo (released in March 2020), https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM et al (2014) Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 67:401–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002

Eaton SM, Clark JD, Cummings CL et al (2022) Pediatric shared decision-making for simple and complex decisions: findings from a Delphi panel. Pediatrics 150(5):e2022057978. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057978

Trevelyan E, Robinson N (2015) Delphi methodology in health research: how to do it? European J Integ Med 7(4):423–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2015.07.002

Gilleland JC, Parshuram CS (2018) Discussing death as a possible outcome of PICU care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 19(8S Suppl 2):S4–S9

Childress A, Bibler T, Moore B et al (2023) From bridge to destination? Ethical considerations related to withdrawal of ECMO support over the objections of capacitated patients. Am J Bioeth 23(6):5–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2022.2075959

Opel DJ (2018) A 4-step framework for shared decision-making in pediatrics. Pediatrics 142(Suppl 3):S149–S156. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0516E

Walter JK, Hwang J, Fiks AG (2018) Pragmatic strategies for shared decision-making. Pediatrics 142(Suppl 3):S157–S162. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0516F

VitalTalk.org: Vital talk resources: learn skills that matter. Available at: https://www.vitaltalk.org/resources/. Accessed 26 Feb 2023.

Wangmo T, De Clercq E, Ruhe KM et al (2017) Better to know than to imagine: including children in their health care. AJOB Empir Bioeth 8(1):11–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2016.1207724

Wijngaarde RO, Hein I, Daams J, Van Goudoever JB, Ubbink DT (2021) Chronically ill children’s participation and health outcomes in shared decision-making: a scoping review. Eur J Pediatr 180(8):2345–2357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04055-6

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the panelists for sharing their experiences and expertise, and for their dedication to improving care for pediatric patients who require ECMO therapy: Kiona Allen, Gail Annich, Ryan Barbaro, Nikhil Chanani, Jonna Clark, Ryan Coleman, Laurence Lequier, Katie Moynihan, David Munson, Ben Sivarajan, and Lillian Su.

Funding

The authors report no funding for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sarah Eaton conceptualized and designed the study, designed the data collection instruments, collected the data, carried out the initial and final analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed, and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Kirsch contributed to the design of the study, assisted with data analysis, assisted with drafting the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Streuli conceptualized the study, assisted with the design of the data collection instruments, assisted with data analysis, reviewed, and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved according to the ethical review process of the medical faculty of the University of Zurich (https://www.ibme.uzh.ch/en/Biomedical-Ethics/Research/Ethics-Review-CEBES). Informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication and identification in the acknowledgments was obtained all participants in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Discontinuation of ECMO with an expected good outcome.

Additional file 2.

Items with disagreement.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eaton, S.M., Kirsch, R.E. & Streuli, J.C. Physician communication with families during pediatric ECMO: results from a Delphi study. Intensive Care Med. Paediatr. Neonatal 2, 8 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44253-024-00030-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44253-024-00030-9