Abstract

Background

To provide substantive, practical guidance on the ethical use of pediatric extra/paracorporeal devices, we first need a comprehensive understanding of existing guidance. The objective was to characterize how ethical guidance for device use in children is provided in published literature and to summarize quantity, quality, and themes.

Data sources

PubMed, Web of Science, and EMBASE databases were systematically searched 2.1.2023.

Study selection

Methodology followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses rapid review. Citations discussing ethical guidance for, initiation/continuation/discontinuation decision-making, or allocation of, devices in children were identified. Devices included tracheostomy/mechanical ventilation (MV), renal replacement therapy (RRT), mechanical circulatory support (MCS), and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). We included policy statements/guidelines, reviews, conceptual articles, and surveys.

Data extraction

A standardized extraction tool was used. Quality was assessed using a multimodal tool.

Data synthesis

Of 97 citations, ethical analysis was the primary objective in 31%. 55% were pediatric-specific. Nineteen percent were high-quality. The USA and Europe were overrepresented with 12% from low- to middle-income countries. Devices included MV (40%), RRT (21%), MCS/ECMO (35%). Only one guideline was identified with a primary goal of ethical analysis of pediatric device use. Three empiric analyses examined patient-level data according to guideline implementation and 24 explored clinician/public perspectives on resource allocation or device utilization. Two non-empiric citations provided pediatric decision-making recommendations.

Conclusions

This comprehensive review of ethical guidance for device use in children identified numerous gaps and limited scope. Future research is warranted globally to promote the beneficial use of devices, minimize harm, and ensure equitable access.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past 50 years, advances in medical technology in the form of devices, including extracorporeal and paracorporeal support, have led to innovative ways to sustain the lives of children with historically life-limiting illnesses [1,2,3,4,5]. However, the allocation of this resource-intense technology across populations, and the initiation, continuation, and termination of these therapies at the individual level, often outpace explicit ethical considerations [6, 7]. Complex medical decisions are made, often under urgent and high-stakes circumstances [8]. Variability in practice across medical centers exists, potentially resulting in inconsistent utilization and disparate outcomes [9, 10]. Furthermore, as potential therapies for disease processes become more complex, prognostic uncertainty lends to more challenging decision-making at the societal, regional, and individual bedside levels. This ever-changing landscape has led to greater ethical tensions regarding the allocation and utilization of these advanced technologies.

To provide substantive, practical guidance on the ethical use of pediatric extracorporeal and paracorporeal devices and medical technology, we first need a comprehensive understanding of existing guidance, characterization of how such guidance is provided in published literature, and to identify gaps. By exploring commonalities and differences in the ethical use of different devices, the opportunity may arise to translate existing guidance across devices. This systematic review summarizes the approaches to providing ethical guidance as well as the quantity, quality, and themes of contemporary published literature on ethical guidance in the use of extracorporeal and paracorporeal devices in children.

Methods

Data sources

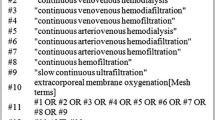

PubMed, Web of Science, and EMBASE databases were systematically searched for citations related to ethical guidance for, ethical utilization of, or ethics of decision-making related to initiation of, continuation of, or withdrawal/discontinuation of, candidacy for, contra/indications to and resource allocation of devices in children. Extracorporeal and paracorporeal devices and medical technology included mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, long-term ventilation, renal replacement therapy (RRT), peritoneal dialysis (PD), hemodialysis, hemofiltration, continuous RRT, mechanical circulatory support ([MCS], extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO], extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ventricular assist devices [VAD], extracorporeal CO2 removal), leuko/plasmapheresis. Search strategies were developed and executed by a medical librarian (AD, Supplement). All study designs were eligible for inclusion. Relevant reviews/meta-analysis were reviewed to ensure that all component studies were included in this systematic review and only synthesized if meeting study inclusion criteria. Search limitations included “date” (2000-present) and “human”. The search was run on 1.20.22 and updated 2.1.2023. After deduplication in EndNote, the final search results were imported into Covidence [11]. Selected articles’ references were mined for additional citations.

Study selection

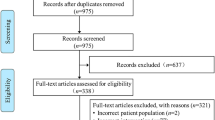

The study methodology followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Rapid Reviews with minimal time-decompression aspects compared to formal systematic review processes [12,13,14,15] (Supplement). Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and then the full text of all publications identified by our searches with a third reviewer (KM) resolving study selection and data extraction conflicts according to the inclusion criteria. We included citations that examined ethical principles or guidance in the use of devices in children that extended beyond clinical factors or patient characteristics such as policy statements from authoritative bodies and institutions, guidelines, expert opinion statements, ethical analyses, empiric studies, and surveys/interviews evaluating attitudes and preferences. Exclusion criteria were (1) non-English language, (2) non-human subjects, (3) unavailable full texts, and (4) adult-specific guidelines or analyses.

Data extraction

Content analysis used a standardized data extraction table tool with inductive thematic analysis. With the overarching goal of synthesizing data to translate any existing ethical guidance across devices as well as to enhance and organize future approaches to ethical guidance, we present data within a publication-type framework (Table 1). To evaluate the quality of ethical analysis and the risk of bias of included citations we used a multimodal tool with seven variables to assess the quality of non-empiric ethical analysis [16,17,18] (Table 1). The quality of ethical analysis was scored (maximum of 8) and categorized into high, medium, or low-quality tertiles.

Results

Of the 3561 citations screened, 97 met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1, Table 2). Publications included 18 (19%) guidelines, 7 (7%) literature reviews, 38 (39%) non-empiric articles, and 34 (35%) empiric studies. The number of publications increased substantially in recent years. While 24% of publications represented a medical society, only 40% explicitly stated a bioethics affiliation. Overall, approximately three-quarters were multicenter and a third multinational with a high proportion from the USA and Europe, with low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) represented in 12%. Just over half the citations were pediatric-specific. In terms of devices, 40% were related to MV, 21% to RRT, and 35% to ECMO/VAD/MCS. Providing ethical guidance on device use was the primary objective in 31% of citations. Identified themes of the ethical principles and frameworks discussed included distributive justice (resource allocation, procedural fairness, equity, proportionality) in 53 (55%) citations, best interest standard and beneficence and non-maleficence in 53 (55%), respect for parental authority, patient autonomy and shared decision making in 51 (53%), utilitarianism in 12 (14%), consent/assent 6 (6%), research ethics in 2 (2%) and the moral equivalence of withholding and withdrawing in 2 (2%). Ethical analyses focused on the determination of decision makers and best interest did not substantially differ between extra/paracorporeal devices with capacity for home/destination use compared with those restricted to in-hospital care. Resource allocation considerations in pandemic-related scarcity focused on hospital device use, while citations on resource distribution from LMIC had a broader scope including home/destination device use. Overall, the quality of ethical analysis varied with only 19% high quality with low risk of bias and a mean quality score of 3.2/8.

Guidelines

Of 18 guidelines or clinical practice recommendations, two were regional/hospital system-based articles and 16 were societal endorsements (Supplemental Table S1). Overall, 7 (39%) were pediatric-specific specific and the primary goal was ethical analysis of device use in 3 (17%). Only 1 publication satisfied both these criteria. Proposed guidelines on end-stage renal disease in children were published in 2000 on behalf of the Spanish Pediatric Nephrology Association, developed from a member survey with subsequent expert consensus and literature review [19]. The guidelines placed emphasis on individual case assessment, and consideration of the best interests with decision-making ideally shared by parents, professionals, the child when appropriate, and ethics committees. Key concepts covered include (1) informed consent, (2) quality of life, (3) withholding or withdrawing treatment, and (4) consideration of economic factors with fair allocation in the setting of scarcity.

Three guidelines focused on ventilation decisions. One advocated for home ventilation decision-making to be shared and to involve the child to the extent that their capacity allows [20]. A German ventilation weaning guideline with pediatric subsections defined two criteria for initiation of mechanical ventilation (1) medically appropriate to achieve a therapeutic goal (based on evidence and individual prognosis) and (2) aligned with patient wishes [21]. This guideline additionally discusses how withholding or withdrawal of therapy in children is necessary and ethically accepted if treatment is expected to provide a short gain in life span out of proportion to the suffering endured, or there is unacceptable suffering without possibility of improvement. Expert recommendations based on a paucity of identified literature in noninvasive respiratory support in children suggest palliative care integration as part of a shared care plan, including the child where appropriate, and acknowledgement that NIV may contribute to symptom control and improvement in quality of life [22].

Five citations examined RRT. One in neonates recommended consensus decision-making for both commencement and withholding of RRT considering (1) short and long-term prognosis, (2) availability of equipment, expertise, and financial resources, the possibility of future transplantation, and (3) quality of life for the child [23]. Four all-ages guidelines were identified. One recommended ‘goal-directed’ peritoneal dialysis such that the prescription met the medical, mental health, social, and financial needs of the individual child and family [24]. The second described how clinicians should first consider the clinical status and survival prognosis, then explain the advantages and disadvantages of potential options (including supportive care without RRT). Eligibility should be assessed at the individual patient level. Mitochondrial, chromosomal disorders, and “severe impairment” should not preclude candidacy for dialysis [25]. The third guideline addressed ethical decision-making to withhold or withdraw dialysis in patients with acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, or end-stage kidney disease with 9 specific pediatric recommendations encompassing four considerations: medical indications, patient preferences, quality of life, and contextual features (e.g., social, economic, legal, and administrative context in which the decision occurs) [26]. A ‘7-Step Process of Ethical Decision-Making in Patient Care’ recommended to identify, analyze, and resolve most ethical issues with the goal to promote values identified as most important while causing the least infringement on the other recognized values in the case. Finally, the Korean clinical practice guideline for hemodialysis recommends that initiation be determined through a careful discussion between the patient and the healthcare provider about the benefits/harms of the treatment and the patient’s values and preferences [27].

Remarkable advances in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant have changed expectations around organ dysfunction reversibility and survival leading to international candidacy recommendations with strong agreement that ECMO be considered in children when there is a reasonable likelihood of recovery within 2–3 weeks and a low risk of malignant recurrence, with secondary considerations including family goals of care [3]. Key points offered for ethical use and informed consent in extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation include discussions of timing and differences by center volume, with consideration for the dynamic nature of patient conditions and the need for frequent review of candidacy and transparent discussions with families around goals of time-limited ECMO support and likely outcomes [28].

The Society of Critical Care Medicine published recommendations to prevent and manage intractable disagreements about the use of devices as “potentially inappropriate” treatments in intensive care units through a fair process of conflict resolution. They emphasized the importance of public engagement efforts and advocated for policies and legislation when life-prolonging technologies should not be used [29]. The American Academy of Neurology guidance for responding to requests for continuing organ support following brain death, whereby after the declaration of death according to the concept of constrained autonomy, there is no “right” to receive desired but unjustified medical treatment [30]. Five of the remaining guidelines were related to resource constraints during the COVID-19 pandemic, where triage protocols and restricting eligibility for devices, including mechanical ventilation and ECMO were recommended [31,32,33,34,35].

Reviews

Only three of the seven literature reviews used systematic search strategies (Supplemental Table S2). Overall, two compared COVID-19 triage recommendations. One review included a comparative analysis of triage principles in device use from selected international professional societies, including Australia/New Zealand, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Pakistan, South Africa, Switzerland, the USA, and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Observed areas of consensus included the importance of prognosis, patient will, transparency, psychosocial support for clinical staff, the role of justice and benefit maximization as core ethical principles, and disagreement; the role of survival versus other outcomes, long-term versus short-term prognosis, age and comorbidities as triage criteria, priority groups, and potential tiebreakers (e.g., ‘lottery’ or ‘first come, first served’) [36]. A second examined the number (n = 27) of publicly available US state ventilator allocation protocols during a public health emergency with a paucity of pediatric guidelines found. These authors raised concerns that associated variation between US state protocols may lead to inequities in ventilator allocation nationally [37]. The remaining 5 were pediatric-specific. A narrative review of ethical decision-making guidance for pediatric ECMO [8] and a summary of pediatric guidelines on withdrawal of VAD in pediatric patients [38] both identified a paucity of guidance. The remaining reviews discussed ethical considerations of respiratory support in children with Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) I [39], variation in ethical decision-making for severely ill neonates across European countries according to the risk of death, age, and parents’ perspectives according to cultural factors [40], and suggestions for ECMO eligibility in premature infants based on emerging outcomes data [41].

Empiric studies

Of 34 quantitative/qualitative analyses, 10 (29%) considered patient-level data (Supplemental Table S3). Three compared patient-level data with guidelines, approaches between centers, or changes over time. Two were pediatric-specific; one showed country-level public health expenditure was a key determinant of health outcomes for children with renal disease describing 67% variation in mortality between European countries [9], and another observed a lack of standardized criteria to withhold or withdraw RRT with differences in parental involvement in the decision-making process [42]. One included the evaluation of a new ‘procedurally fair’ guideline in patients of all ages describing RRT eligibility and utilization of the therapy according to clinical and demographic features [43]. The remaining seven discussed ethical issues of a case or case series with themes related to devices in children meeting Death by Neurological Criteria [44], prolonged ECMO support [45], novel or expanding device use to new populations [46], “bridge to nowhere” vs “destination ECMO” [47, 48], as well as informed consent and parental autonomy in children who identify as Jehovah’s witness [49, 50].

There were 24 (86%) surveys or qualitative analyses of focus group interview data or forums that evaluated perspectives on devices and decision-making (Supplemental Table S4). The majority surveyed clinicians (physicians, nurses, or social workers) and 5 (22%) were public perceptions. Overall, 15 (63%) were pediatric-specific. One survey ascertained institutional guidelines on COVID-19 pandemic resource allocation [51]. Eight analyzed the prioritization of clinician or public preferences in the allocation of scarce resources and variably the social or demographic influences on these perspectives. Of these, six were pandemic-related [52,53,54,55,56,57], two were specific to resource limitation in LMIC settings [58, 59], and one both [52]. The relative weight of determinants studied differed and included survival chances, illness severity, the greatest number, age (life cycle), social factors including religion, nationality, pregnancy and having young children, healthcare workers or noble occupations, and preference for lottery or reparation-based tiebreakers. For Indian providers and Sub-Saharan African nephrologists, there were additional tensions reported navigating between patient resource limitations, and those of the institution recognizing other patients with similar needs, with further considerations in weighing benefits versus harm for the patient related to family economic well-being and family reputation within the community. The remaining 15 (61%) related to candidacy or device initiation/discontinuation decision-making or center-level approaches, ethical challenges in clinical scenarios surrounding the initiation, discontinuation, and end-of-life, and social or demographic influences on these perspectives. Of these, 9 focused on ventilators [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68], 2 ECMO [69, 70], 3 VAD [71,72,73], and 1 neonatal RRT [74].

Non-empiric citations

Of 38 conceptual, theoretical, or normative ethical analyses or commentaries, four represented formal societies or work groups (Supplemental Table S5). Overall, 20 (53%) were pediatric-specific and 22 (58%) had ethical analysis of device use as the primary aim. Twelve citations satisfied both these criteria. Three related to respiratory support in SMA [75,76,77] with one specifically providing recommendations regarding not offering ventilatory support in SMA [75]. The remaining nine pediatric studies that primarily focused on ethical device use discussed ethical considerations or challenges in ECMO use, and the complexity of medical decision-making regarding ECMO utilization and discontinuation. The specific emphasis in these papers was on neonates [78, 79], children with neurologic diagnoses [80], and heart disease or cardiac arrest [81,82,83]. Two manuscripts described applying ethical frameworks including principlism to guide the utilization of ECMO for all pediatric populations [84] and during a pandemic [85]. One provided recommendations for a process-based approach to ECMO decision-making [86].

The remaining eight pediatric-specific citations covered long-term ventilation and tracheostomy [87, 88], trisomy 18 [89], life-saving therapies in undocumented children [90], peritoneal dialysis (PD) [91], end-of-life care with MCS [92], brain death [93], and pediatric patient prioritization during COVID-19 pandemic [94]. Of the remaining 18 all-ages studies, 10 examined the ethics of triage principles, including defining criteria to guide fair allocation of scarce resources or manage staffing crises during the COVID-19 pandemic [95,96,97,98,99,100], or ethics of equitable access to RRT [101,102,103,104], and an additional 2 reviewed definitions of DNC with an ethical analysis of continued physiologic support of patients meeting death by neurological criteria [105, 106]. One reviewed ethical principles of ECMO utilization based on cost analysis and the ethics of research trials with ECMO, specifically RCTs [7]. Other topics included withdrawal of left VADs [107], withholding vs withdrawing life-sustaining treatments [108], and ethical use of RRT [109,110,111].

Discussion

This comprehensive rapid systematic review summarizes the extant published literature on the ethical guidance for the use of extracorporeal and paracorporeal devices in children. Ethical guidance is essential due to the complexity and high-stakes nature of medical decisions in addition to the extensive resource utilization associated with pediatric device use. Overall, we noted a paucity of high-quality literature across all publication types (literature reviews, empiric studies, non-empiric articles, and guidelines) including identifying only one pediatric guideline focused on the ethical use of a device. Findings offered limited specific ethical guidance that was overall narrow in scope, US or European predominant, and lacking a community perspective. Critical observations from data synthesis have illustrated important knowledge gaps with implications for future research and conceptual work for the field including expanding the scope of and improving the quality of ethical analyses, enhancing global and community collaboration, advancing health equity, and developing medical community ethics literacy.

In a majority of manuscripts, the utilization of applied ethical frameworks was narrow in focus. Principlism (e.g., ethical principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, respect for autonomy, and justice), best interest standard, and resource prioritization fairness featured heavily as the most common ethical frameworks and themes considered [112,113,114,115,116]. Variability in the application of the best interest standard as a guiding framework and/or intervention principal even between developed/western societies underscores the inadequacies of a narrow scope [115]. An expanded incorporation of other ethical frameworks, such as relational ethics/ethics of care, rights-based ethics, and communitarian ethics may lend additional perspectives for a broader number of stakeholders [116,117,118,119,120,121]. For example, when clinicians give primacy to autonomy, even though this was not intended in the original principlist framework, inequities in access to devices and disparate outcomes may result. Notably, half of the manuscripts mentioned respect for autonomy, zones of parental discretion, and/or shared decision-making as important frameworks to guide complex medical decision-making regarding the utilization of devices. While shared decision-making is touted as the ideal model for medical decision-making in the USA, there remains extensive discussion in the literature regarding its application in pediatrics [122,123,124,125]. Incorporating fundamental tenets of palliative care, including inter-disciplinary teamwork and high-quality communication across all disciplines, as essential components of shared decision-making, may also provide additional insight. Collaborative communication that emphasizes active and empathetic listening, eliciting values, maintaining transparency, and providing clarity on potential risks and benefits may improve the process of decision-making, particularly at the bedside [126, 127].

While most manuscripts were written by multiple authors and almost a quarter were medical society endorsements, authors primarily represented the USA and Europe. A minority represented LMIC. Acknowledging the limitation of the English language in the search strategy, this lack of inclusion of diverse perspectives from the broader international community may lend to uninformed guidance and further exacerbate inequities. The recent surge in identified publications in the last 3 years is attributable to the rationing of healthcare resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. While many LMIC have faced rationing of medical resources due to limited resources for decades, the COVID-19 pandemic brought the ethical challenges of resource allocation to the forefront of healthcare decisions in many middle and high-income countries [36, 128]. Increased collaboration among international medical centers may facilitate exchanges in experiences, processes, and knowledge which may ultimately improve equitable access and outcomes with policy implications globally [129].

Across all types of manuscripts, ethical analyses related to device use were low in quality, and the primary objective in less than a third. Importantly a high proportion of reviewed guidelines had no ethical analysis or non-clinical considerations beyond patient-level characteristics. We excluded 84% of the 115 guidelines reviewed at the full-text level, and of the clinical practice guidelines included in this systematic review, most had short sections related to ethics or briefly mentioned considerations specific to children or devices. Only one (< 1% of all guidelines reviewed) guideline focused on the ethical use of a device in children. Literature reviews confirm insufficient data to advise uniform clinical applications across numerous devices with no substantive ethical guidance identified and most often concluded that more ethical guidance is needed [130]. Furthermore, the theoretical, and normative ethical analyses had moderate to high risk of bias. Of these non-empiric manuscripts only three offered specific pediatric recommendations to apply ethical frameworks to guide utilization of, or decision making for a device. All offered ethical arguments related to pediatric ECMO candidacy, allocation, or decision-making. Quality ethical analysis, ethical literacy, and education around the ethical use of devices are critical to improving the medical community’s interpretation and understanding of the implementation of clinical criteria surrounding initiation, continuation, and discontinuation.

A multi-disciplinary and community perspective is also lacking from the identified literature. Only 17% of the surveys or qualitative studies identified analyzed the perspectives of the public. We live in a pluralist society and an era where patients and families have increasing access to medical information of varying quality and a greater expectation to participate in their own treatment plans. Because of implicit and explicit biases within the medical community, particularly among clinicians, the importance of including a broader group of stakeholders in providing ethical guidance cannot be understated [131]. Incorporating an expansive scope of perspectives from the community (e.g., recipients of device use, families of recipients of device use, the families of those who were not offered or did not have access) and members of multi-disciplinary clinical teams (e.g., nursing, social work, palliative care, bioethics, spiritual care) is essential to decrease variability in processes, access, and clinical practices which may ultimately result in inequitable outcomes.

Empiric patient-level analyses and surveys identified substantial variability in clinical practices related to pediatric device use. We only identified 3 studies that considered and statistically analyzed the ethical implications of guideline implementation, including 2 in children [9, 42]. The importance of improving the quality of empirical outcomes data and critical evaluation of contemporary practices in pediatric device use may lend to an improved ability to prognosticate and guide ethical decision-making. Identified variability may reflect prognostic uncertainty, the lack of standardization of practices, and the paucity of explicit clinical and ethical guidance, potentially playing an important role in exacerbating inequities in access and outcomes. Collaboration globally to create collective databases and develop standards of “excellence” among centers that offer device utilization in children may help reduce explicit and implicit biases, promote center integrity, encourage high-quality services, and ultimately result in improved outcomes for all children.

Limitations

Our review methodology followed rapid systematic review procedures with only two time-decompression procedures undertaken (no advance review protocol publication and omission of gray literature sources) to differ from traditional systematic reviews with other formal processes to ensure rigor included such as comprehensive search strategy, updated review, dual blinding and quality assessment [12,13,14,15] (See supplement). While there are inherent challenges in systematic reviews in bioethics [132], a key objective was to understand how ethical guidance is offered in contemporary health care in terms of publication types, in order to develop a framework for providing future ethical guidance [14, 133]. Manuscript-type heterogeneity precluded meta-analysis beyond the thematic analysis of devices restricted to in-hospital care versus those with capacity for home/destination use. In the absence of an existing formal, validated approach to evaluate the rigor and quality of ethical analysis, we developed a multimodal tool incorporating seven variables that encompass critical elements for quality non-empiric analysis by combining methodology from opinion pieces and ethics literature [16,17,18]. The search was limited to English language publications; however, a parallel global approach via alternate methodology was simultaneously conducted. Defining ‘ethical’ guidance is somewhat subjective. This review is comprehensive including those guidelines that offered any considerations for device use beyond clinical variables or discussed shared decision-making approaches, even if minimal ethical guidance was provided. This means recommendations that device initiation “be decided through a careful discussion between the patient and the healthcare provider about the benefits/harms of the treatment and the patient’s values and preferences” met inclusion criteria. However, devices had to be explicitly mentioned.

Future directions

This work establishes a foundation for the future provision of substantive ethical guidance on extra/paracorporeal device use in children to address the identified gaps. Key implications for future research and conceptual work for the field include the need to work collaboratively among centers to encapsulate ethical considerations for the best use of pediatric devices that are inclusive, representative of a wide range of challenges and diverse, international, multi-disciplinary, and community perspectives. The importance of high-quality ethical analysis is emphasized including the need for multi-modal publication types to enhance future research approaches. Other important steps to address identified gaps include establishing ethical literacy and competence within the medical community. Finally, finding commonalities and differences between extracorporeal and paracorporeal devices globally will be helpful in establishing baseline tools and frameworks for equitable and ethical pediatric device use.

Conclusions

There is a paucity of high-quality guidance for the ethical utilization of extracorporeal and paracorporeal device use in children. As pediatric medical complexity continues to increase, additional high-quality empirical research and normative ethical analyses are urgently needed. Collaboration among international medical centers and inclusion of all stakeholders who utilize these devices in children may help create important ethical guidance to develop processes that reduce inequities and improve outcomes for all children in need of advanced medical technology.

Abbreviations

- LMIC:

-

Low–middle-income countries

- MV:

-

Mechanical ventilation

- RRT:

-

Renal replacement therapy

- MCS:

-

Mechanical circulatory support

- VAD:

-

Ventricular assist device

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- SMA:

-

Spinal muscular atrophy

References

Clark JD, Baden HP, Berkman ER et al (2022) Ethical considerations in ever-expanding utilization of ECLS: a research agenda. Front Pediatr 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.896232

Rahman M, Jeffreys J, Massie J (2021) A narrative review of the experience and decision-making for children on home mechanical ventilation. J Paediatr Child Health 57:791–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15506

Di Nardo M, Ahmad AH, Merli P et al (2023) Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in children receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immune effector cell therapies: An International and Multi-Disciplinary Consensus Statement. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal 6:116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00336-9

Himmelfarb J, Vanholder R, Mehrotra R, Tonelli M (2020) The current and future landscape of dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol 16:573–585. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-020-0315-4

Chopski SG, Moskowitz WB, Stevens RM, Throckmorton AL (2017) Mechanical circulatory support devices for pediatric patients with congenital heart disease. Artif Organs 41:E1–E14. https://doi.org/10.1111/aor.12760

Faraoni D, Nasr VG, DiNardo JA (2016) Overall hospital cost estimates in children with congenital heart disease: analysis of the 2012 kid’s inpatient database. Pediatr Cardiol 37:37–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-015-1235-0

Crow S, Fischer AC, Schears RM (2009) Extracorporeal life support: utilization, cost, controversy, and ethics of trying to save lives. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 13:183–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089253209347385

Moynihan KM, Dorste A, Seigel BD et al (2021) Decision-making, ethics and end-of-life care in pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a comprehensive narrative review. Pediatr Crit Care Med 22(9):806–812. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0000000000002766

Chesnaye NC, Schaefer F, Bonthuis M et al (2017) Mortality risk disparities in children receiving chronic renal replacement therapy for the treatment of end-stage renal disease across Europe: an ESPN-ERA/EDTA registry analysis. Lancet 389:2128–2137. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30063-6

Moynihan KM, Dorste A, Alizadeh F et al (2023) Health disparities in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation utilization and outcomes: a scoping review and methodologic critique of the literature. Crit Care Med 51(7):843–860. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005866

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB et al (2016) De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc 104:240–243. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014

Watt A, Cameron A, Sturm L et al (2008) Rapid reviews versus full systematic reviews: an inventory of current methods and practice in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 24:133–139. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462308080185

Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R et al (2012) Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev 1:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-10

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W et al (2015) A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med 13:224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6

Implementation Science Collaborative Rapid review vs. systematic review: what are the differences? University Research Co Available at: https://iscollab.org/rapid-review-systematic-review/. Accessed 1.3.2021

McArthur A, Klugarova J, Yan H, Florescu S (2015) Innovations in the systematic review of text and opinion. Int J Evid Based Healthc 13(3):188–195. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000060 PMID: 26207851

Jansen M, Ellerton P (2018) How to read an ethics paper. J Med Ethics 44:810–813. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2018-104997

McArthur A, Klugarova J, Yan H, Florescu S (2020) Chapter 4: Systematic reviews of text and opinion. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (eds) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis

Riaño I, Malaga S, Callis L et al (2000) Towards guidelines for dialysis in children with end-stage renal disease. Pediatr Nephrol 15:157–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004679900169

Amin R, MacLusky I, Zielinski D et al (2017) Pediatric home mechanical ventilation: A Canadian Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline executive summary. Can J Respir Crit Care, Sleep Med 1:7–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2017.1300463

Schönhofer B, Geiseler J, Dellweg D et al (2021) Prolonged weaning: S2k Guideline Published by the German Respiratory Society. Respiration 99:982–1083. https://doi.org/10.1159/000510085

Fauroux B, Abel F, Amaddeo A, et al (2022) ERS statement on paediatric long-term noninvasive respiratory support. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01404-2021

Zurowska AM, Fischbach M, Watson AR et al (2013) Clinical practice recommendations for the care of infants with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD5). Pediatr Nephrol 28:1739–1748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-012-2300-z

Brown EA, Blake PG, Boudville N et al (2020) International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis practice recommendations: Prescribing high-quality goal-directed peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 40:244–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896860819895364

Doi K, Nishida O, Shigematsu T et al (2018) The Japanese Clinical Practice Guideline for acute kidney injury 2016. Ren Replace Ther 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-018-0177-4

Rockville M (2010) Shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis. The Renal Physicians Association https://doi.org/www.renalmd.org

Jung JY, Yoo KD, Kang E et al (2022) Executive summary of the Korean Society of Nephrology 2021 clinical practice guideline for optimal hemodialysis treatment. Korean J Intern Med 37(4):701–718. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2021.543

Guerguerian A-M, Sano M, Todd M et al (2021) Pediatric extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation ELSO guidelines. ASAIO J 67:229–237. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAT.0000000000001345

Bosslet GT, Pope TM, Rubenfeld GD et al (2015) An Official ATS/AACN/ACCP/ESICM/SCCM policy statement: responding to requests for potentially inappropriate treatments in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 191:1318–1330. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201505-0924ST

Russell JA, Epstein LG, Greer DM et al (2019) Brain death, the determination of brain death, and member guidance for brain death accommodation requests: AAN position statement. Neurology 92:228–232. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000006750

Badulak J, Antonini MV, Stead CM et al (2021) Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for COVID-19: updated 2021 Guidelines from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. ASAIO J 67:485–495. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAT.0000000000001422

Macmillan P, Frye J, Bunnalai T, Kaups K (2020) Crisis Standards of Care Guidelines for the COVID-19 pandemic: Fresno Resource Allocation Guide (FRAG). Cureus 13. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.19662

Prekker ME, Brunsvold ME, Bohman JK et al (2020) Regional planning for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation allocation during coronavirus disease 2019. Chest 158:603–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.026

Shekar K, Badulak J, Peek G et al (2020) Extracorporeal life support organization coronavirus disease 2019 interim guidelines: a consensus document from an International Group of Interdisciplinary Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Providers. ASAIO J 66:707–721. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAT.0000000000001193

Vergano M, Bertolini G, Giannini A et al (2020) Clinical ethics recommendations for the allocation of intensive care treatments in exceptional, resource-limited circumstances: the Italian perspective during the COVID-19 epidemic. Crit Care 24:165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-02891-w

Jöbges S, Vinay R, Luyckx VA, Biller-Andorno N (2020) Recommendations on COVID-19 triage: international comparison and ethical analysis. Bioethics 34:948–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12805

Piscitello GM, Kapania EM, Miller WD et al (2020) Variation in ventilator allocation guidelines by US state during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open 3:e2012606. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12606

Hollander SA, Axelrod DM, Bernstein D et al (2016) Compassionate deactivation of ventricular assist devices in pediatric patients. J Heart Lung Transplant 35:564–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2016.03.020

Grychtol R, Abel F, Fitzgerald DA (2018) The role of sleep diagnostics and non-invasive ventilation in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Paediatr Respir Rev 28:18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2018.07.006

Gerdfaramarzi MS, Bazmi S (2020) Neonatal end-of-life decisions and ethical perspectives. J Med Ethics Hist Med 13. https://doi.org/10.18502/jmehm.v13i19.4827 PMID: 33552452

Burgos CM, Frenckner B (2020) Premature and extracorporeal life support: is it time? ASAIO J 66:41. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAT.0000000000001555 PMID: 34593681

Fauriel I, Moutel G, Moutard ML et al (2004) Decisions concerning potentially life-sustaining treatments in paediatric nephrology: a multicentre study in French-speaking countries. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19:1252–1257. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfh100

Moosa MR, Maree JD, Chirehwa MT, Benatar SR (2016) Use of the ‘Accountability for Reasonableness’ Approach to Improve Fairness in Accessing Dialysis in a Middle-Income Country. PLoS One 11:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164201

Flamm AL, Smith ML, Mayer PA (2014) Family members’ requests to extend physiologic support after declaration of brain death: a case series analysis and proposed guidelines for clinical management. J Clin Ethics 25:222–237

Ares GJ, Buonpane C, Helenowski I et al (2019) Outcomes and associated ethical considerations of long-run pediatric ECMO at a single center institution. Pediatr Surg Int 35:321–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-019-04443-y

Wolfson RK, Kahana MD, Nachman JB, Lantos J (2005) Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after stem cell transplant: clinical decision-making in the absence of evidence. Pediatr Crit Care Med 6:200–203. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Pcc.0000155635.02240.9c

Shankar V, Costello JP, Peer SM et al (2014) Ethical dilemma: offering short-term extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for terminally ill children who are not candidates for long-term mechanical circulatory support or heart transplantation. World J Pediatr Congenit Hear Surg 5:311–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150135113509820

Truog RD, Thiagarajan RR, Harrison CH (2015) Ethical dilemmas with the use of ECMO as a bridge to transplantation. Lancet Respir Med 3:597–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00233-7

Orr RD (2002) Clinical ethics case consultation. Ethics Med 18:33–34

Peterec SM, Bizzarro MJ, Mercurio MR (2018) Is extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for a neonate ever ethically obligatory? J Pediatr 195:297–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.11.018

Matheny Antommaria AH, Gibb TS, McGuire AL et al (2020) Ventilator triage policies during the COVID-19 pandemic at U.S. hospitals associated with members of the Association of Bioethics program directors. Ann Intern Med 173:188–194. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1738

Abbasi-Kangevari M, Arshi S, Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Kolahi AA (2021) Public Opinion on Priorities Toward Fair Allocation of Ventilators During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Nationwide Survey. Front Public Health 9:753048. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.753048

Gandhi R, Piscitello GM, Parker WF, Michelson K (2021) Variation in COVID-19 resource allocation protocols and potential implementation in the Chicago Metropolitan Area. AJOB Empir Bioeth 12:266–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2021.1983667

MacGregor RM, Antiel RM, Najaf T et al (2020) Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019-related illness. Pediatr Crit Care Med 21:893–897. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0000000000002432

Wilkinson D, Zohny H, Kappes A et al (2020) Which factors should be included in triage? An online survey of the attitudes of the UK general public to pandemic triage dilemmas. BMJ Open 10:e045593. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045593

Biddison ELD, Gwon HS, Schoch-Spana M et al (2018) Scarce resource allocation during disasters: a mixed-method community engagement study. Chest 153:187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.001

Kappes A, Zohny H, Savulescu J et al (2022) Race and resource allocation: an online survey of US and UK adults’ attitudes toward COVID-19 ventilator and vaccine distribution. BMJ Open 12:e062561. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062561

Miljeteig I, Norheim OF (2006) My job is to keep him alive, but what about his brother and sister? How Indian doctors experience ethical dilemmas in neonatal medicine. Dev World Bioeth 6:23–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8847.2006.00133.x

Ashuntantang G, Miljeteig I, Luyckx VA (2022) Bedside rationing and moral distress in nephrologists in sub- Saharan Africa. BMC Nephrol 23:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-022-02827-2

Benson RC, Hardy KA, Gildengorin G, Hsia D (2012) International survey of physician recommendation for tracheostomy for Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type I. Pediatr Pulmonol 47:606–611. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.21617

Cuttini M, Casotto V, Orzalesi M (2006) Ethical issues in neonatal intensive care and physicians’ practices: a European perspective. Acta Paediatr Suppl 95:42–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/08035320600649721

Dybwik K, Nielsen EW, Brinchmann BS (2012) Ethical challenges in home mechanical ventilation: a secondary analysis. Nurs Ethics 19:233–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011414967

Feltman DM, Du H, Leuthner SR (2012) Survey of neonatologists’ attitudes toward limiting life-sustaining treatments in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol 32:886–892. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2011.186

Geevasinga N, Ryan MM (2007) Physician attitudes towards ventilatory support for spinal muscular atrophy type 1 in Australasia. J Paediatr Child Health 43:790–794. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01197.x

Kinali M, Manzur AY, Mercuri E et al (2006) UK physicians’ attitudes and practices in long-term non-invasive ventilation of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Pediatr Rehabil 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13638490600622613

Schneider K, Metze B, Bührer C et al (2019) End-of-life decisions 20 years after EURONIC: neonatologists’ self-reported practices, attitudes, and treatment choices in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. J Pediatr 207:154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.12.064

Needle JS, Mularski RA, Nguyen T, Fromme EK (2012) Influence of personal preferences for life-sustaining treatment on medical decision making among pediatric intensivists. Crit Care Med 40:2464–2469. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318255d85b

Morparia K, Dickerman M, Hoehn KS (2012) Futility: unilateral decision making is not the default for pediatric intensivists. Pediatr Crit Care Med 13:e311–e315. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0b013e31824ea12c

Kuo KW, Barbaro RP, Gadepalli SK et al (2017) Should extracorporeal membrane oxygenation be offered? An international survey. J Pediatr 182:107–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.12.025

Chapman RL, Peterec SM, Bizzarro MJ, Mercurio MR (2009) Patient selection for neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: beyond severity of illness. J Perinatol 29:606–611. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2009.57

Kaufman BD, Hollander SA, Zhang Y et al (2019) Compassionate deactivation of ventricular assist devices in children: a survey of pediatric ventricular assist device clinicians’ perspectives and practices. Pediatr Transplant 23:e13359. https://doi.org/10.1111/petr.13359

Knoepke CE, Siry-Bove B, Mayton C et al (2022) Variation in left ventricular assist device postdischarge caregiver requirements: results from a mixed-methods study with equity implications. Circ Heart Fail 15:777–784. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.122.009583

Friedland JM, Anna L, Svetlana J et al (2022) Patient and device selection in pediatric MCS : a review of current consensus and unsettled questions. Pediatr Cardiol 43:1193–1204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-022-02880-6

Linder E, Burguet A, Nobili F, Vieux R (2018) Neonatal renal replacement therapy: an ethical reflection for a crucial decision. Arch Pediatr 25:371–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2018.06.002

Ryan M, Kilham H, Jacobe S et al (2007) Spinal muscular atrophy type 1: is long-term mechanical ventilation ethical? Commentary. J Paediatr Child Health 43:238–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01052.x

Mitchell I (2006) Spinal muscular atrophy type 1: What are the ethics and practicality of respiratory support? Paediatr Respir Rev 7:S210–S211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2006.04.200

Rul B, Carnevale F, Estournet B et al (2012) Tracheotomy and children with spinal muscular atrophy type 1: ethical considerations in the French context. Nurs Ethics 19:408–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011429014

Di Nardo M, Ore AD, Testa G et al (2019) Principlism and personalism. comparing two ethical models applied clinically in neonates undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Front Pediatr 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00312

Kirsch R, Munson D (2018) Ethical and end of life considerations for neonates requiring ECMO support. Semin Perinatol 42:129–137. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2017.12.009

Moynihan KM, Basu S, Kirsch R (2022) Discretion over discrimination: toward good decisions for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use in patients with neurological comorbidities*. Pediatr Crit Care Med 23:943–946. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000003078

Ryan J (2015) Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for pediatric cardiac arrest. Crit Care Nurse 35:60–69. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2015655

Carter MA (2017) Ethical considerations for care of the child undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. AORN J 105:148–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2016.12.001

Mavroudis C, Mavroudis CD, Green J et al (2012) Ethical considerations for post-cardiotomy extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Cardiol Young 22:780–786. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1047951112001540

Carlisle EM, Loeff DS (2020) Emerging issues in the ethical utilization of pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Curr Opin Pediatr 32:411–415. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000901

Kissoon N, Bohn D (2010) Use of extracorporeal technology during pandemics: ethical and staffing considerations. Pediatr Crit Care Med 11:757–758. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e288a4

Moynihan KM, Jansen M, Siegel BD et al (2022) Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation candidacy decisions: an argument for a process-based longitudinal approach. Pediatr Crit Care Med 23(9):e434–e439. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002991

Brookes I (2019) Long-term ventilation in children. Paediatr Child Heal (United Kingdom) 29:167–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paed.2019.01.013

Trachsel D, Hammer J (2006) Indications for tracheostomy in children. Paediatr Respir Rev 7:162–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2006.06.004

Kochan M, Cho E, Mercurio M et al (2021) Disagreement about surgical intervention in trisomy 18. Pediatrics 147. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.2020-010686

Young J, Flores G, Berman S (2004) Providing life-saving health care to undocumented children: Controversies and ethical issues. Pediatrics 114:1316–1320. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1231

Zaritsky J, Warady BA (2011) Peritoneal dialysis in infants and young children. Semin Nephrol 31:213–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.01.009

Joong A, Derrington SF, Patel A et al (2019) Providing compassionate end of life care in the setting of mechanical circulatory support. Curr Pediatr Rep 7:168–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40124-019-00206-4

Choong KA, Rady MY (2018) Re A (A Child) and the United Kingdom Code of Practice for the Diagnosis and Confirmation of Death: Should a Secular Construct of Death Override Religious Values in a Pluralistic Society? HEC Forum 30:71–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-016-9307-y

Antiel RM, Curlin FA, Persad G et al (2020) Should pediatric patients be prioritized when rationing life-saving treatments during COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics 146. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-012542

Chu Q, Correa R, Henry TL et al (2020) Reallocating ventilators during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Is it ethical? Surg (United States) 168:388–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2020.04.044

Kucewicz-Czech E, Damps M (2021) Triage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther 52:312–315. https://doi.org/10.5114/AIT.2020.100564

Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ (2020) The Toughest Triage - Allocating Ventilators in a Pandemic. N Engl J Med 382:1973–1975. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005689

Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R et al (2020) Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382:2049–2055. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb2005114

White DB, Lo B (2020) A framework for rationing ventilators and critical care beds during the covid-19 pandemic. JAMA 323:1773–1774. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5046

Butler CR, Webster LB, Diekema DS (2022) Staffing crisis capacity: a different approach to healthcare resource allocation for a different type of scarce resource. J Med Ethics:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme-2022-108262

Luyckx VA, Moosa MR (2021) Priority setting as an ethical imperative in managing global dialysis access and improving kidney care. Semin Nephrol 41:230–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2021.05.004

Wearne N, Davidson B, Motsohi T et al (2021) Radically rethinking renal supportive and palliative care in South Africa. Kidney Int Reports 6:568–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2020.11.024

Harris DCH, Davies SJ, Finkelstein FO et al (2019) Increasing access to integrated ESKD care as part of universal health coverage. Kidney Int 95:S1–s33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.12.005

Luyckx VA, Martin DE, Moosa MR et al (2020) Developing the ethical framework of end-stage kidney disease care: from practice to policy. Kidney Int Suppl 10:e72–e77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kisu.2019.11.003

du Toit J, Miller F (2016) The ethics of continued life-sustaining treatment for those diagnosed as brain-dead. Bioethics 30:151–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12178

Bernat JL, Capron AM, Bleck TP et al (2010) The circulatory-respiratory determination of death in organ donation. Crit Care Med 38:963–970. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c58916

Jericho BG (2018) Withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 31:179–184. https://doi.org/10.1097/aco.0000000000000570

Sprung CL, Paruk F, Kissoon N et al (2014) The Durban World Congress Ethics Round Table Conference Report: I. Differences between withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatments. J Crit Care 29:890–895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.06.022

Kalantar-Zadeh K, Wightman A, Liao S (2020) Ensuring choice for people with kidney Failure - Dialysis, supportive care, and hope. N Engl J Med 383:99–101. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2001794

Teitelbaum I, Glickman J, Neu A et al (2021) KDOQI US Commentary on the 2020 ISPD Practice Recommendations for Prescribing High-Quality Goal-Directed Peritoneal Dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 77:157–171. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.09.010

Martin DE, Harris DCH, Jha V et al (2020) Ethical challenges in nephrology: a call for action. Nat Rev Nephrol 16:603–613. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-020-0295-4

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF (2008) Principles of biomedical ethics. Oxford Univ Press

Diekema DS (2011) Revisiting the best interest standard: uses and misuses. J Clin Ethics 22:128–133

Kopelman LM (1997) The best-interests standard as threshold, ideal, and standard of reasonableness. J Med Philos 22:271–289. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/22.3.271

Ross LF (2020) Reflections on charlie gard and the best interests standard from both sides of the atlantic ocean. Pediatrics 146:S60–S65. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0818L

Lantos JD (2018) Best interest, harm, God’s will, parental discretion, or utility. Am J Bioeth 18:7–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2018.1504502

Etzioni A (2011) On a communitarian approach to bioethics. Theor Med Bioeth 32(5):363–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-011-9187-8

Tong R (1998) The ethics of care: a feminist virtue ethics of care for healthcare practitioners. J Med Philos A Forum Bioeth Philos Med 23:131–152. https://doi.org/10.1076/jmep.23.2.131.8921

Wightman A, Kett J, Campelia G, Wilfond BS (2019) The relational potential standard: rethinking the ethical justification for life-sustaining treatment for children with profound cognitive disabilities. Hast Cent Rep 49:18–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.1003

Rashotte J (2006) Relational ethics in critical care. Aust Crit Care 19:4–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1036-7314(06)80016-0

Nelson HL (2000) Feminist bioethics: where we’ve been, where we’re going. Metaphilosophy 31:492–508

Weiss EM, Clark JD, Heike CL et al (2019) Gaps in the implementation of shared decision-making: illustrative cases. Pediatrics 143. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3055

Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W et al (2016) Shared decision making in ICUs: an American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement. Crit Care Med 44:188–201. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001396

Morrison W, Clark JD, Lewis-Newby M, Kon AA (2018) Titrating clinician directiveness in serious pediatric illness. Pediatrics 142:S178–S186. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0516I

Moynihan KM, Jansen MA, Liaw SN et al (2018) An ethical claim for providing medical recommendations in pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 19:e433–e437. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000001591

Feudtner C (2007) Collaborative communication in pediatric palliative care: a foundation for problem-solving and decision-making. Pediatr Clin N Am 54:583–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2007.07.008

Moynihan KM, Purol N, Alexander PMAP et al (2021) A communication guide for pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0000000000002758

Abagero A, Ragazzoni L, Hubloue I et al (2022) A review of COVID-19 response challenges in ethiopia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19:11070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711070

Morrow BM, Agulnik A, Brunow de Carvalho W et al (2023) Diagnostic, management, and research considerations for pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome in resource-limited settings: from the second pediatric acute lung injury consensus conference. Pediatr Crit care Med a J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc 24:S148–S159. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000003166

Olson T, Anders M, Burgman C et al (2022) Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults and children: a review of literature, published guidelines and pediatric single-center program building experience. Front Med 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.935424

FitzGerald C, Hurst S (2017) Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 18:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8

Birchley G, Ives J (2022) Fallacious, misleading and unhelpful: The case for removing ‘systematic review’ from bioethics nomenclature. Bioethics 36:635–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.13024

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C et al (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 18:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Funding

Pediatric Paracorporeal Extracorporeal Therapies Summit (PPETS) funding through NIH R13 HD104433. Funders had no influence on the manuscript content.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Katie Moynihan conceptualized and designed the study, screened citations, resolved conflicts, created the data abstraction tool, interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Jonna Clark conceptualized and designed the study, screened citations, drafted aspects of the manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Roxanne Kirsch conceptualized and designed the study, screened citations, interpreted the data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Seth Hollander designed the study, screened citations, interpreted the data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Melanie Jansen, Dr. Joe Brierley, Ryan Coleman, Dr. Bettina von Dessauer, and Dr. James A. Thomas designed the study, screened citations, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Ms. Anna Dorse guided the rapid review methodology, developed and designed the search strategies, conducted the literature search, imported into and managed the Covidence software, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Ms. Emma Thibault screened citations, created the data abstraction tool, managed the data sets, created the tables, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table S1.

Guidelines. Supplemental Table S2. Literature reviews. Supplemental Table S3. Empiric citations; patient data. Supplemental Table S4. Empiric citations; survey data. Supplemental Table S5. Non-empiric citations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moynihan, K.M., Clark, J.D., Dorste, A. et al. Ethical guidance for extracorporeal and paracorporeal device use in children: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. Paediatr. Neonatal 2, 1 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44253-023-00022-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44253-023-00022-1