Abstract

Background

Inpatient mental health facilities required COVID-19 testing for all patients, including asymptomatic ones, due to perceived high susceptibility.

Aim

This study examined how the policy affected patient care and hospital resources.

Method

A retrospective review was conducted on asymptomatic psychiatric patients admitted to the psychiatric emergency room between July and December 2020, analyzing COVID-19 test results, conversion rate, length of stay (LOS), and demographic variables.

Results

Among asymptomatic patients (N = 2020), 2.5% (n = 51) tested positive, with 7.8% (n = 4) experiencing mild symptoms. The average hospital length of stay was 8 days, with 90.2% discharged home and 9.8% transferred to outside mental health inpatient facilities. Chi-square testing found no significant differences in age, gender, or housing status between positive and negative patients (p’s > 0.05), except for a significant difference in positivity rates among Hispanic patients (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

The positivity rate among asymptomatic mental health patients was low. The policy of universal testing increased hospital spending and resource utilization, including unnecessary testing and hospital admissions, leading to longer stays. These findings underscore the need to assess the efficacy of COVID-19 testing policies and reconsider resource allocation based on evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

The worldwide outbreak of the novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) in January 2020 plunged the world into a catastrophic event for which hospitals were unprepared. National, regional, and local agencies enacted mandatory stay-at-home orders to stop the disease’s spread. Locally, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (LAC DPH) initiated the "Safer at Home Order for Control of COVID-19" (Safer at Home) in March 2020 [1]. This order closed all non-essential businesses, including mental health clinics and other public services and resources on which mental health patients relied. The closure of mental health clinics, "nonessential" public spaces, and related lockdown significantly impacted access to mental health care, including limiting gatherings. Furthermore, various public mental health resources, such as gymnasiums, in-person support groups, and chemical dependency sponsors that mental health patients employed for mental health well-being were inaccessible due to the quarantine. This led to reduced access, disrupted medication supply, increased stigma and discrimination, closure of psychosocial and therapeutic services, and increased workload and stress for the Emergency Department (ED) and inpatient unit providers [2]. Consequently, many psychiatric mental health patients adhering to their treatment and functional in the community did not have access to the necessary resources to maintain their mental health conditions and hence setting off trajectory of decompensation.

Consequences of the Safer at Home guidelines were social isolation, barriers to in-person mental health visits, challenges in obtaining medications, and limited access to coping mechanism resources [2]. Many healthcare institutions tried to fill the in-person support gap by phone, video, or in-person sessions while wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) [3]. However, the platforms and modalities (remote or in-person) were challenging for patients with language, cognitive, knowledge, technological, psychological, and physical barriers [4]. This particularly impacted the most vulnerable of mental health patients of low socioeconomic status, cognitive disabilities, and elderly mental health patients [3, 4]. Due to the closures and social distancing protocols, exercise facilities, in-person support groups, and chemical dependency-sponsored activities were inaccessible. In addition, with the closures of mental health treatment and resources, many patients decompensated and sought treatment in emergency rooms, resulting in a significant increase in mental health patients seen in emergency rooms and mental health holds for patients who were otherwise stable and functional before the pandemic [5].

Emergency departments absorbed the cascading impact of these policies as mental health encounters increased, in addition to well-known community psychiatric resource shortages [5]. In reviewing the objective tool to measure ED overcrowding, the National Emergency Department Overcrowding Study (NEDOCS) shows a gradual increase from 2018 to 2020 in average wait time to see a provider (2018-26 min, 2020-1 h and 33 min) [6]. NEDOCS is a validated tool to objectively quantify overcrowding in Emergency Departments and assess ED overcrowding [7]. The NEDOCS score is derived from a formula requiring the following variables: the number of ED patients, the number of ED beds, the number of hospital beds, the number of ventilators in use in the ED, the waiting time for the longest admission, the waiting room time of the last patient called to a bed, and the number of admits in the ED [7].

At the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, there was little to no knowledge, information, or data about the transmissibility of the COVID-19 virus, particularly among the mental health population. Due to fear of the unknown, drastic and extreme measures were taken to protect the population. Thus, individuals faced impediments to psychiatric mental health care while the hospital tried to care for dying COVID-19 patients, manage psychiatric patients, and balance resources. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified high-risk factors and populations for contracting the disease, many of which are common in mental health populations (see Table 1) [8,9,10]. Many of the factors identified by the CDC, such as disabilities, depression, schizophrenia disorders, mood disorders, developmental and behavioral disorders, drug and substance use disorders, unhoused and densely congregated housing individuals and correctional facilities are found in mental health populations, leading to the perception that mental health populations are potentially more susceptible to COVID-19 [8,9,10]. This guidance fostered the perception that the mental health population was at greater risk and highly susceptible to COVID-19. As such, the standard of practice for COVID-19 testing changed to require facilities to test all mental health patients for COVID-19 before inpatient mental health admission, regardless of symptomatology [11]. If a non-mental health patient presented to the ED as asymptomatic or with mild symptoms, the patient was sent home and informed to follow social isolation guidelines [8]. However, the mental health population was different; they were tested regardless of symptomatology. Adopting this policy had consequences, including reduced throughput in the ED and delayed the determination of patient disposition, which increased ED length of stay (LOS) and competed with acuity in medical decision making to admit to inpatient and psych ER beds. Many regions in the United States require COVID-19 testing of patients before mental health inpatient admission to determine the patient’s COVID status [12]. During the onset of the pandemic, testing resources were limited since even non-acute symptomatic COVID-19 patients who did not require admission were not tested to conserve resources. However, due to the relatively unknown nature of COVID-19, many mental health facilities required blanket testing on all patients, including asymptomatic COVID-19 patients [12]. The blanket testing led to unintended consequences where asymptomatic COVID-19 patients had to be admitted to medical/surgical inpatient units to await the results of their tests. Initial polymerase chain reaction (PCR) laboratory results for a "Person Under Investigation (PUI)" during the initial phase of the pandemic had a turnaround time of 1 week, which eventually improved to 2–3 days and finally, by the end of the improved to a turnaround time of less than 24 h (due to the non-urgent need for results). Due to the length of turnaround time, patients could not wait in acute emergency beds as they were needed for critically ill patients. Therefore, patients were admitted to medical/surgical units. Once patients received their results, they were able to be transferred to mental health inpatient facilities. In the rarity that an asymptomatic patient tested positive for COVID-19, there was no place to accommodate COVID-19-positive mental health patients on psychiatric, legal holds, or California’s Lanterman-Petris-Short (LPS) (1967) Statute [13]. Hence, patients on mental health holds who tested positive for COVID-19 and required mental health inpatient admission were denied admission at mental health inpatient hospitals. These individuals were in limbo in the ED (medical and psych) and on medical/surgical units and eventually were hospitalized or remained in medical/surgical units. COVID-19 positive units had not been explored early in the pandemic [14]. In the context of healthcare resource allocation, it is crucial to consider the cost implications of admitting psychiatric patients to medical/surgical wards compared to primary psychiatric care facilities. Psychiatric care units are typically more cost-effective than medical/surgical wards due to their specialized nature and focus on mental health treatment. When psychiatric patients are admitted to medical/surgical wards, the hospital incurs additional costs associated with providing specialized psychiatric care within a non-specialized setting. Research suggests that psychiatric inpatient stays cost less than medical/surgical admissions. According to the research, primary mental health and substance use disorder admission costs $7,100 per stay (mean LOS 6.4 days), a primary medical diagnosis and no mental health diagnosis costs $11,500 per stay (LOS 4.2), and a dual admission diagnosis of a primary medical diagnosis (i.e., COVID) and a secondary diagnosis of mental health or substance use disorder costs $14,300 per day (LOS 5.4) [15]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the strain on medical resources was particularly acute, with hospitals facing beds and medical staff shortages [12]. Admitting psychiatric patients to medical/surgical wards without medical necessity further strained an already overburdened system, potentially impacting the quality of care provided to all patients. Furthermore, research shows that testing asymptomatic COVID-19 individuals incurs direct and indirect costs [16, 17]. Initially, COVID-19 assays necessitate costly equipment, reagents, and the labor of technologists. A recent survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation, encompassing 93 hospitals, revealed that the median cost of a COVID-19 test amounted to $148 [16]. Thus, adopting the policy of testing asymptomatic mental health patients for COVID-19, inadvertently compounded limited medical/surgical admissions, which imposed a significant financial and resource burden on the hospital’s capacity.

Evidence-based practice entails gathering and synthesizing information that is necessary for informed policymaking. With few studies and resource-based COVID-19 strategies, LAC adopted policies to best serve the mental health population. However, limited information exists on the prevalence of COVID-19 positivity rate in asymptomatic psychiatric mental health patients admitted to inpatient mental health facilities on an LPS hold. To date, three medical investigations have reported asymptomatic COVID-19 prevalence. A retrospective study evaluated the prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 among gynecological surgery patients at a reproductive clinic and found a 1.44% infection rate [18]. Another mental health emergency room study found a 2.2% infection rate among asymptomatic patients [19]. A study of perioperative patients found 0.13% infection in asymptomatic patients [20]. In reviewing these studies, it shows that the prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 cases in LAC was very low, thus prompting the study to determine the prevalence rate given proximity to downtown. This study aims to raise awareness and knowledge of the asymptomatic mental health community in Los Angeles County by evaluating; (1) if the mental health population is at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 virus, (2) If the unique location of our facility proximity to higher concentration of the unhoused population increase the risk, (3) determine the prevalence of inner-city asymptomatic mental health populations; (4) Examine the demographically distribution and compare the result to known and reported risk in the general population. Results from this study will be consequential, contribute to growing knowledge and inform future policies for mental health populations during a pandemic.

1.2 Statement of the problem

Limited information exists on the prevalence of COVID-19 positivity rate in asymptomatic psychiatric mental health patients admitted to inpatient mental health facilities on an LPS hold. To date, only 3 studies in LAC have reported asymptomatic COVID-19 prevalence in clinical settings, with positivity rates ranging from < 1% to < 3% [18,19,20]. However, there is a lack of comprehensive data on the mental health population.

Thus, this study addresses this gap by conducting a retrospective analysis of EHR data from the Psychiatric Emergency Room (PER) to determine the positivity rate of asymptomatic mental health patients. The findings from this study are intended to provide valuable insights for policymakers and healthcare providers to develop evidence-based, informed policies for the mental health population in future planning and implementation.

1.3 Purpose

This retrospective study aimed to (1) ascertain the prevalence of COVID-19-positive cases and conversion rates in the asymptomatic mental health patient population admitted to the PER during the initial critical phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) discuss the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations regarding the mental health population as a high-risk group for COVID-19; and (3) identify demographic and clinical differences between asymptomatic COVID-19 positive and negative mental health patients in the PER.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

This study was a retrospective cohort analysis of mental health patients admitted to the PER between July and December 2020. Convenience sampling methods were used for data collection as part of standard COVID-19 screening procedures. The project was deemed “exempt” and approved by The University of Southern California Institutional Review Board (IRB). The study is determined to be exempt from 45 CFR 46 according to §46.104(d) as category (4). Furthermore, the need for informed consent was waived by IRB. All authors confirm that the study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

2.2 Setting and participants

The setting for this retrospective study was a public safety net, an LPS-designated academic medical center proximal to downtown Los Angeles, CA. The community supported by our hospital is primarily Hispanic (96.2%). The median household income is $55,000, 17.9% of the populace lives in poverty, and 14.7% of the populace under the age of 65 has no health insurance [21]. The PER had nearly 100,000 visits between January 2018 and December 2020, an average of approximately 33,000 visits annually [22]. The convenience sampling criteria consisted of adult patients brought to the PER on an involuntary mental health hold between July and December 2020 via law enforcement officers, Emergency Medical Services (EMS) agencies (such as the Los Angeles City and Los Angeles County Fire Department), private ambulances, outpatient clinics, privately run acute hospitals, and self-referrals. Participants were a non-randomized convenient sample of patients seen in the PER that was self-referred, or someone else recognized that the person needed emergency mental health care.

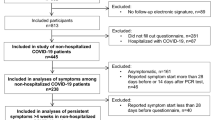

Upon arrival at the PER, a medical provider conducted a Medical Screening Exam (MSE), which included the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Screening Questions (see Table 2) [7]. If the patient experienced any COVID-19 symptoms or responded in the affirmative to the screening questions, indicating they were symptomatic, the patient was transferred to the Medical ED for complete medical evaluation and COVID-19 testing. If the psychiatric patient did not experience any COVID-19 symptoms and responses to all the screening questions were negative, indicating they were asymptomatic, they were admitted to the PER and completed COVID-19 testing. Segregation of the patient from other patients allowed for isolation and social distancing until the laboratory’s COVID-19 test resulted (see Fig. 1 for flowchart). Patients were excluded from the study if they (1) were < 18 years old; (2) were admitted primarily for medical reasons; (3) were experiencing COVID-19 symptoms based on CDC guidelines; (4) required a medical appliance or equipment that could be used to harm themselves or others; or (5) were forensic/custody patients requiring a mental health hold. The number of participants in the cohort was determined by the number of patients seen in the PER that met the study criteria.

Flowchart to determine study participants In PER, all patients received an MSE. The PER transferred all symptomatic patients to the Medical ER and admitted them to the Medical/Surgical units (not a study participant). PER tested all asymptomatic COVID-19 patients entering the area (This is the study population). The medical/surgical unit received all the asymptomatic COVID-19-positive patients from the PER. A mental health inpatient hospital would accept patients with a COVID-19 negative test. ER = Emergency Room

2.3 Variables/data sources/measurements

Data collection included select demographic and outcome variable data. Demographic variables of interest included age, gender, ethnicity, and housing status. Patients self-reported information on a patient registration questionnaire, and hospital staff transcribed the data into the Electronic Health Record (EHR). Patient outcome variables included COVID-19 test results, COVID-19 conversion, LOS (ED LOS, Med/Surg unit LOS, and total hospital LOS), and disposition.

As part of the patient’s course of treatment to determine disposition, physicians ordered COVID-19 testing. The hospital’s laboratory initially used the Xpert Xpress (Cepheid) SARS-CoV-2 assay for the COVID-19 Test; however, in September 2020, due to the assay’s discontinuation, the hospital transitioned to the Simplexa (Diasorin) COVID-19 Direct test. Both tests are real-time RT-PCR assays with comparable detection limits. During the laboratory's verification test, the Simplexa assay demonstrated 100% concordance with the Xpert Xpress assay and 100% agreement with the CDC SARS-CoV-2 assay, a well-known reference standard.

2.4 Quantitative variables

Determination of the conversion rate of a participant was defined as a patient who arrived at the PER without exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms (as outlined in Table 2) but later tested positive for the COVID-19 test. If the participant subsequently exhibited COVID-19 symptoms, the patient was counted as converted to symptomatic COVID-19-positive. A chart review was conducted on all COVID-19-positive participants' charts, including notes and vital signs recorded by nurses and physicians and discharge summaries.

Determination of the LOS of a participant used various points extracted from the EHR. Determination of the ED LOS used the time stamp in the patient’s chart when the staff registered the patient. When staff transferred a patient to another area, the staff discharged the patient from the ED, which denotes a timestamp in the EHR. The difference between these two times determines the ED LOS. To determine the medical/surgical LOS, when the patient arrived at the medical/surgical unit, the staff activated the account, which placed a timestamp in the EHR. Subsequently, when the patient was discharged/transferred from the unit, it was denoted by a timestamp in the EHR. The difference in time between these two timestamps determined the Medical/surgical LOS. The time was determined by adding the ED and medical/surgical LOS. The total LOS was the total time spent in the ED and the medical/surgical unit in the hospital.

Patient disposition, retrieved from the EHR, was the final step in the care pathway after a provider’s evaluation and treatment, either in the ED or medical/surgical unit. The provider determined if the participant continued to meet the LPS mental health hold criteria, indicating whether the patient would be discharged home or required additional treatment and was safe to transfer to a mental health inpatient facility.

2.5 Statistical methods

The analyses included descriptive statistics on the characteristics of the two groups, asymptomatic COVID-19 positive and negative mental health patients. Using Chi-Square tests with corresponding odds ratios, inferential statistics assessed the variables of interest on outcome measures. The data was analyzed using SPSS v. 26.

3 Results

3.1 Participants

During the timeframe between July 2020 and December 2020, there were a total of 2,614 patients brought to the PER for evaluation. Of those, 594 (23%) were symptomatic, requiring medical clearance. The remaining 2020 (77%) patients were screened using the CDC guidelines and deemed asymptomatic for COVID-19. Asymptomatic patients were tested for COVID-19, and test results, positive or negative, determined the comparison groups (see Fig. 1).

3.2 Descriptive data

Chi-square analyses comparing the demographic characteristics of COVID-19 positive versus negative mental health patients revealed no statistically significant differences in age, gender, or housing status (all p’s > 0.05). The groups statistically differed in ethnicity, with significantly more Hispanic patients and fewer “others” in the COVID-19 positive group than in the negative group (\({x}^{2}=\) 9.55; p = 0.02). See Table 3 for results.

3.3 Outcome data/main results

Table 3 shows a 2.52% total positivity rate (51/2020). Notably, of the patients admitted for positive COVID-19 test, 92.2% (47/51) remained asymptomatic, and only 7.8% (n = 4) exhibited mild COVID-19 symptoms. Examining the asymptomatic COVID-19-positive patient’s LOS revealed that the average ED LOS was 12 h (SD ± 11 h), and the average medical/surgical LOS and total LOS were 8 days, respectively. Further examination shows that 90.2% (46/51) had the mental health hold rescinded and were discharged home. The other 9.8% were transferred to a psychiatric inpatient mental health bed once cleared by an infectious disease physician. The 4 patients who developed COVID-19 symptoms were discharged home with appropriate COVID-19 follow-up instructions. None required supplemental oxygen or additional medical treatment for their mild COVID-19 symptoms. Additional analyses describe the positivity rates by patient characteristics. Examining the age data, results show a 3.2% positivity rate for ages 18–30, 2.2% positivity for ages 31–50, and 2.5% positivity for ages 51 years and older. By gender, results revealed a 2.9% positivity rate for males and 1.9% for females. Notably, the positivity rate varied by ethnicity, with 3.7% Hispanic, 3.4% African American or Black, 1.0% Caucasian or White, 0% Asian, and 1.7% others/unknown. Finally, the positivity rate of those with listed addresses was 2.6%, and those listed as unhoused was 2.3%.

4 Discussion

4.1 Key results

Our study revealed a 2.5% prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19-positive mental health. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that individuals who were asymptomatic and tested positive for COVID-19 converted to symptomatic due to mild COVID-19 symptoms at a rate of 7.8%. These findings support our hypotheses of a low asymptomatic COVID-19 prevalence rate and a low conversion rate of asymptomatic COVID-19 mental health patients. The practice of testing all mental health patients regardless of symptomatology is unwarranted based on the low prevalence and conversion rate in the population studied. These findings highlight the importance of assessing the efficacy of COVID-19 testing and policies on resource allocation.

4.2 Limitations

The limitations of the study are few. Two distinct COVID-19 PCR assays were used because of rapidly advancing technology, which may have resulted in differing sensitivity and specificity. The sample size of the COVID-19-positive participants may limit the generalizability of the results due to the uniqueness of this population. The COVID-19 negative group in the cohort study was lost to follow-up because they were transferred to facilities to which we do not have access or permission to view their medical records; thus, we could not ascertain if any of the COVID-19 negative groups became positive or symptomatic or determine their LOS for comparison. This study was limited by our inability to assess, extract and include data assessing of protective factors against mental health decompensate during the pandemic.

4.3 Interpretation

In conclusion, the study reveals that a small number of asymptomatic patients tested positive for COVID-19 when screened utilizing CDC guidelines for COVID-19. Comparing the findings of this study of the 2.5% asymptomatic COVID-19 prevalence to the previous studies conducted in the same county, 1–3% asymptomatic COVID-19 prevalence contrary to initial concerns, the mental health population does not appear to be at higher risk of COVID-19-positive in as compared to the general population of Los Angeles County. This raises the question of whether changing the standard of practice from only testing moderate to severe COVID-19 patients to testing for COVID-19 regardless of symptomatology in the mental health population was warranted and whether only screening with the CDC guidelines for symptomatology should have been sufficient in guiding treatment for mental health patients without having additional testing for COVID-19. Also, the analysis of COVID-19 data by ethnicity reveals a notable disparity, with the Hispanic population exhibiting a statistically significant higher proportion of asymptomatic COVID-19-positive cases compared to other ethnic groups. This implies that the disparity in COVID-19 positivity rates among Hispanics is unlikely to result from random chance. There may be a genuine correlation between individuals of Hispanic ethnicity and asymptomatic positive COVID-19 test results within this demographic. Under optimal conditions, the science of improvement guidelines would have been followed, and these findings would’ve provided evidence that the policy needed amending; however, due to the unprecedented circumstances of the pandemic, the evaluation of the change was justifiably delayed.

4.4 Generalizability

This study contributes to the growing knowledge of the positivity rate among the inner-city asymptomatic mental health population during the pandemic. These findings underscore the need for further research to understand the intersection of mental health and COVID-19 risk factors better. The study also emphasizes the importance of using evidence-based practices, such as quality improvement (QI) models and IHI’s systematic approach, when implementing changes or interventions in healthcare settings. Healthcare organizations can reduce costs, avoid unnecessary waste, and maintain high-quality patient care by focusing on improving quality and efficiency. Regardless of the severity of the situation, they will ensure evidence-based decision-making tailored to the specific population. Future studies should examine the impact of asymptomatic COVID-19 testing on other patient populations, treatment decision-making, and ED overcrowding. Also, examining the association between the presence of asymptomatic COVID-19-positive patients and the Hispanic population is crucial. This can shed light on potential factors contributing to the higher prevalence of COVID-19 cases within the Hispanic community. Understanding these associations can help develop targeted strategies to reduce transmission. This study occurred prior to vaccine availability; future studies would benefit from assessing the influence of vaccinations on COVID-19 prevalence among mental health patients. This study can inform more effective public health strategies for these vulnerable groups during the pandemic and future health crises.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data due to sensitivity and privacy laws, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from Los Angeles General Medical Center.

References

County of Los Angeles public health. Safer at home order for control of COVID-19. Los Angeles. 2020.

Davies T, Daniels I, Roelofse M, Dean C, Parker J, Hanlon C, Thornicroft G, Sorsdahl K. Impacts of COVID-19 on mental health service provision in the Western Cape, South Africa: The MASC study. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(8): e0290712. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0290712.

Von Humboldt S, Low G, Leal I. Health service accessibility, mental health, and changes in behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study of older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):4277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074277.

Diaz A, Baweja R, Bonatakis JK, Baweja R. Global health disparities in vulnerable populations of psychiatric patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. World J Psychiatry. 2021;11(4):94–108. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v11.i4.94.

Ferwana I, Varshney LR. The impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on mental health patient populations in the United States. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55879-9.

Weiss SJ, Derlet R, Arndahl J, Ernst AA, Richards J, Fernández-Frankelton M, Nick TG, Derlet R, Arndahl J, et al. Estimating the degree of emergency department overcrowding in academic medical centers: results of the National ED Overcrowding Study (NEDOCS). Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(1):38–50. https://doi.org/10.1197/j.aem.2003.07.017.

Weiss SJ, Derlet R, Arndahl J, Ernst AA, Richards J, Fernández-Frankelton M, Nick TG, Derlet R, Arndahl J, et al. Estimating the degree of emergency department overcrowding in academic medical centers: results of the National ED Overcrowding Study (NEDOCS). Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(1):38–50. https://doi.org/10.1197/j.aem.2003.07.017NEDOCS.

County of Los Angeles Public Health. County of Los Angeles Declares Local Health emergency in response to new novel Coronavirus Activity. County of Los Angeles Public Health Web site. 2020. http://www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/phcommon/public/media/mediapubhpdetail.cfm?prid=2248. Accessed 28 Apr 2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). People at increased risk of severe illness Department of Health and Human Services. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov; https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html. Accessed 28 Apr 2021.

Centers for disease control and prevention, (CDC). Ending Isolation and precautions for people with COVID-19: Interim Guidance. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov; https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html#:~:text=People%20who%20are%20infected%20but,a%20mask%20through%20day%2010. Accessed 28 Nov 2022.

Bojdani E, Rajagopalan A, Chen A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impact on psychiatric care in the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289: 113069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113069.

Ojha R, Syed S. Challenges faced by mental health providers and patients during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic due to technological barriers. Internet Interv. 2020;21: 100330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2020.100330.

Lanterman-Petris-Short Act. 1967;sec. 5000 et seq. 1967. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=WIC&division=5.&title=&part=1.&chapter=1.&article. Accessed 28 Apr 2021.

Brody BD, Shi Z, Shaffer C, Eden D, Wyka K, Alexopoulos GS, Parish SJ, Kanellopoulos D. COVID-19 infection rates in patients referred for psychiatric admission during a regional surge: the case for universal testing. Psychiatry Res. 2021;298: 113833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113833.

Owens RA, Fingar KR, McDermott KW, Muhuri PK, Heslin KC. Integrative management of substance use disorders and co-occurring mental health disorders. advanced practice psychiatric nursing. 2019.

Srinivasan V, Gohil SK, Abeles SR, Yokoe DS, Cohen SH, Ramirez-Avila L, Prabaker KK, Maurice S. Finding a needle in a haystack: the hidden costs of asymptomatic testing in a low incidence setting. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.288.

Mohammadinia L, Saadatmand V, Sardashti HK, Darabi S, Bayat FE, Rejeh N, Vaismoradi M. Hospital response challenges and strategies during COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1167411. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1167411.

Armstrong A, Berger M, Lee V, Tandel M, Kwan L, Brennan K, Zain AS. Rates of COVID-19 infection among in vitro fertilization patients undergoing treatment at a university reproductive health center. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2022;9(39):2163–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-022-02581-2.

Cardenas J, Roach J, Kopelowicz A. Prevalence of COVID 19 positive cases presenting to a psychiatric emergency room. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(7):1240–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00816-7.

Singer JS, Cheng EM, Murad DA, et al. Low prevalence (0.13%) of COVID-19 infection in asymptomatic pre-operative/pre-procedure patients at a large, academic medical center informs approaches to perioperative care. Surgery. 2020;168(6):980–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2020.07.048.

United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts East Los Angeles CDP, California; United States. 2022. https://www.census.gov; https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/eastlosangelescdpcalifornia,US/PST045222. Accessed 28 Nov 2022.

Bruckner TA, Huo S, Huynh M, Du S, Young A, Ro A. Psychiatric emergencies in los angeles county during, and after, initial COVID-19 societal restrictions: an interrupted time-series analysis. Commun Ment Health J. 2023;59(4):622–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-022-01043-4.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the nursing leadership and the nursing education department at the hospital where the data were collected for their support. Also, this manuscript is dedicated to the hard-working staff of the psychiatric emergency department, who experienced COVID-19 and continued to provide high-quality patient care amid an ever-changing environment. THANK YOU!

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AO and SO conceived the study and determined the methodology. AO and SO collected and analyzed the data with assistance from CC. AO took the lead in writing and organizing the manuscript. All five authors contributed to writing sections of the manuscript. All five authors reviewed the final manuscript before submitting it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Olmedo, A., Okundolor, S., Mallet-Smith, S. et al. Testing asymptomatic mental health patients for COVID-19 overburdens hospital resources. Discov Health Systems 3, 59 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00125-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00125-2