Abstract

Background

Healthcare workers experienced significant disruptions to both their personal and professional lives throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. How healthcare workers were impacted varied, depending on area of specialization, work setting, and factors such as gender. Dietetics is a female-dominated profession and the differential impact on women of the COVID-19 pandemic has been widely reported. While researchers have explored Registered Dietitians’ (RDs) experiences during the pandemic, none have looked explicitly at their experiences of redeployment. The objectives of this study were to better understand: (i) the impact of COVID-19 (and related redeployments) on the work-lives of RDs, (ii) what types of COVID-19 related supports and training were made available to these RDs, and (iii) the impact of RD redeployment on access to RD services.

Methods

An online survey was administered in June 2022. Any RD that that was publicly-employed in Canada during the pandemic was eligible to participate. The survey included questions related to respondent demographics, professional details, redeployment and training. We conducted descriptive analyses on the quantitative data.

Results

The survey was completed by 205 eligible RDs. There were notable differences between public health and clinical RDs’ redeployment experiences. Only 17% of clinical RDs had been redeployed, compared to 88% of public health RDs. Public health RDs were redeployed for longer and were more likely to be redeployed to roles that did not required RD-specific knowledge or skills. The most commonly reported mandatory training was for proper use of personal protective equipment. The most commonly reported reasons for a lengthy absence from work were anxiety about contracting COVID-19, school closures and limited child care availability.

Conclusions

Public health RDs are at the forefront of campaigns to reduce the burden of chronic disease, improve health equity and enhance the sustainability of food systems. Close to 90% of these RDs were redeployed, with many seeing their typical work undone for many months. More research is needed to quantify the consequences of going without a public health nutrition workforce for an extended period of time and to understand the differential impact gender may have had on work experiences during the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Healthcare workers globally experienced significant disruptions to both their personal and professional lives throughout the COVID-19 pandemic [1,2,3,4]. How healthcare workers were impacted varied [4], depending on their profession, area of specialization, work setting, regional variation in COVID-19 infection rates, differences in public health management of COVID-19 and on their personal characteristics and living situation [2]. The differential impact on women of the COVID-19 pandemic has been widely reported [5,6,7], with women shouldering the lion’s share of caregiving responsibilities when schools closed.

Members of the allied health professions make-up an important part of the global health workforce. Previous research conducted in Australia has indicated that, compared to physicians, nurses and midwives, Australian allied health professionals (AHPS) were more likely to experience changes in their work tasks during the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. Registered Dietitians (RDs), specifically, are AHPs that specialize in human nutrition. RDs work in a variety of settings, but their practical training typically has three main components: clinical, public health/community and foodservice administration. Clinical typically refers to work that is one-on-one with individual clients, patients or resident and most often takes place in hospitals, long-term care facilities and outpatient clinics (including primary care centres) Public health and community roles do not typically involve individualized nutrition therapy; RDs in these roles will take part in the development of population- and/or community-level policies and initiatives that require ongoing relationship-building and collaboration across departments at varied levels of government, across economic sectors and with non-governmental organizations. Graduate-level education is typically required for RDs in public health and community practice. Their work is critical to the achievement of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2 and 3 and contributes to achievement of multiple other SDGs. The SDGs have been set to protect our planet, end poverty and improve all people’s lives and prospects by 2040 [8]. SDG 2 is to “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture,” while SDG 3 is to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages” [9]. Such RD roles are often embedded within governments and health authorities. Those employed in foodservice administration are frequently in positions of leadership overseeing support services (including foodservice, housekeeping and laundry) within a variety of institutions, including hospitals, correctional facilities, universities, and long-term care facilities. The largest proportion of dietitians are employed in clinical roles [10, 11]. Notably, the dietetic profession is made up almost entirely of women (> 90% [2, 12,13,14]). While researchers across the globe [2, 10, 13, 15,16,17,18,19,20]) have explored RDs’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, none have explicitly looked at their experiences of redeployment. To better inform health human resource governance decisions, and to avoid healthcare workers’ feeling disempowered during surge event-related resource reallocation, more research is needed [7, 21].

The Government of Canada defines deployment as a “transfer of a person from one position to another” [22]. Redeployment occurs in different work settings and there have been benefits and challenges associated with redeployment, both for individuals and for organizations [23]. Implications for redeployed staff include the added stress of being assigned work tasks they haven’t performed before or tasks that fall outside their occupational training, and losing (typically temporarily) access to colleagues they have built a connection with in their pre-pandemic job/role [4]. The speed and breadth of redeployments that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented [24].

RDs were redeployed in a number of ways during the pandemic, including: being redeployed within the dietetic sector [2, 25]; switching from in-person provision of nutrition care to telehealth (including use of videoconferencing platforms) [15,16,17,18,19,20, 26]; and acting in roles related to public health management of COVID-19, including contact tracing [23, 25, 27]. As far as work hours go, RDs may have experienced an increase or decrease in work hours, with some being laid off from work entirely [2, 13, 25]. These changes in RD work may have been voluntary or involuntary [23, 27]. Job options were reduced for some by challenges associated with relocation, such as quarantine requirements or travel restrictions [13, 25].

The objectives of this study were to better understand: (i) the impact of COVID-19 (and related redeployments) on the work-lives of RDs employed in the Canadian public sector, (ii) what types of COVID-19 related supports and training were made available to these RDs, and (iii) RD-perceived impacts of redeployment on clients/patients/communities’ access to RD services.

2 Methods

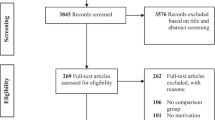

In June of 2022, we placed targeted recruitment messages on Twitter™ and posted study information, including a link to the online survey, in key, relevant groups on Facebook™ and on LinkedIn™. Hashtags (e.g., #dietitiansarekey) were added to increase message reach. The survey was available in English only. By this time, there had been six waves of COVID-19 in Canada [28]. Anyone who was publicly-employed as a RD during the COVID-19 pandemic was eligible to complete the online survey. The survey, hosted on LimeSurvey™, contained questions related to respondent demographics, professional details, redeployment and training. Respondents were eligible to provide an e-mail address for entry into a lottery for a $135 gift card to HelloFresh™. Survey responses remained separate from any identifying information.

Puzzlingly, despite no immediate incentives for survey participation, we encountered issues with bots “completing” the online survey. “Bots,” which is an abbreviation of robots, are software applications capable of performing automated tasks faster than could be accomplished by humans; these “bots” can be tasked with filling in surveys repeatedly and quickly [29]. We applied several strategies identified in the literature to identify (and remove) illegitimate survey respondents from the analytic sample, such as checking for consistency and appropriateness of quantitative and qualitative responses [30] (e.g., age range of 18–24 alongside > 3 years as an RD) and removing outliers based on response times [29,30,31]. A benchmark time for survey completions was determined by having JF complete the survey (5 min 44 s). We were also attentive to multiple sequential responses with similar selections for demographic variables, typically the first option in the drop-down menu, when considering the validity of a response. Process-wise, we reviewed all responses independently and identified those exhibiting signs of being fraudulent before meeting to compare. SH and JF had 95% initial agreement on which responses were invalid (385/408 identified) and discussed those that had only been identified by one of us (23/408) before deciding whether they should be removed. The average valid completion time was 13 min. Ultimately, 67% of the 605 survey responses were identified as illegitimate. Exploratory data analysis and descriptive statistics were conducted using Stata/IC™ 15.1.

3 Results

The final sample included 205 RDs who were publicly-employed in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. See Table 1 for participant demographics.

The most significant representation in the sample was from RDs working in public health and clinical settings, with clinical settings including acute care—tertiary, acute-care—non-tertiary, primary care and long-term care. There were notable differences between public health and clinical RDs’ redeployment experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 2).

For example, 88% of public health RDs had been redeployed during the pandemic, as compared to only 17% of clinical RDs. Of redeployed public health RDs, 68% were tasked with COVID-19 related duties; in these contact tracing and call centre roles, RDs were not explicitly employing their RD-specific knowledge and skills. In contrast, 35% of redeployed clinical RDs reported being redeployed to provide RD services to inpatients.

Redeployed public health RDs were also more likely to be redeployed for longer, with 68% having been redeployed for more than three months, as compared to only 18% of redeployed clinical RDs. While 66% of redeployed public health RDs reported that their regular duties remained undone during their redeployments, this was true for only 12% of redeployed clinical RDs. Redeployed public health RDs were more likely to report consequences associated with their redeployment, when compared to redeployed clinical RDs: approximately 85% of public health RDs reported that there was less advocacy in their community and that nutrition programs had been put on hold as a result of their redeployment. Overall, redeployed public health RDs reported more negative experiences of their first deployment and felt less prepared for these redeployments than their clinical counterparts. It is notable that the majority of redeployed public health and clinical RDs did not view their contributions as being considered “essential” in their organizations.

Many of the respondents participated in training during the COVID-19 pandemic, some of which was related to changes in their work setting and available resources (see Table 3 for details). Despite working from home becoming mandatory for some RDs, 11% of those required to work from home were not provided with any of the necessary resources. Close to one-third of respondents had inadequate access to PPE at some point during the pandemic and, for some (11% of those who had an absence longer than three weeks), inadequate access to PPE prevented them from working.

The majority (60%) of respondents were offered training in connection with COVID-19; the most common mandatory training was for proper use of PPE. More than half of respondents had to be absent from work for three or more weeks during the pandemic, with more than 50% attributing their absence to anxiety about contracting COVID-19. The second and third most prevalent reasons for these absences were limited child care availability (pre-school) (32%) and school closures for school-aged children (39%).

4 Discussion

Public health RDs are at the forefront of local, provincial, national and global campaigns to reduce the burden of chronic disease, improve health equity and enhance the sustainability of food systems [32]. Their work is critical to the achievement of SDGs addressing world hunger, food insecurity, sustainable agriculture and population-level health and well-being [8, 9]. These RDs experienced the most change in their work-lives during the COVID-19 pandemic, with most being deployed away from their regular role for more than three months while their work remained undone (see Table 2). Undoubtedly there will be long lasting impacts on the health of populations, as the sustainability of healthcare systems is dependent on the effective implementation of public health strategies that specifically target food environments and their impacts on the health of communities [8, 32, 33].

We know that feeling undervalued in the workplace is a reason AHPs, including dietitians, may leave their jobs and/or employers [34, 35]. It is concerning that public health RDs in Canada, on average, had negative experiences in their first (typically lengthy) redeployment of the COVID-19 pandemic and that most felt underprepared to perform the duties in their new role. It is also unsurprising, knowing this, that Canadian public health RDs felt that the organizations they worked for considered their contributions to be nonessential and of only moderate value. Considering that close to 90% of public health RDs in our sample had been redeployed, it will be particularly important that Canadian healthcare organizations give public health RDs: (i) the space, time and resources to debrief and recover from a potentially traumatic redeployment experience [23, 36,37,38,39], and (ii) demonstrate widely and loudly their appreciation, respect and support for the initiatives and “outputs” of public health RDs working within their organizations [36, 39,40,41]. Otherwise, there may be significant attrition from this workforce [35, 42], which will have long-lasting, far-reaching, negative impacts on population health [8, 43].

More than half of our respondents had been absent from work for more than three weeks during the pandemic period (see Table 3). There is a lack of data to facilitate comparison of this rate and duration to what may have been observed in other allied health professions. Our survey respondents were able to select more than one reason for their absence and more than half indicated that anxiety about contracting COVID-19 contributed to their absence from work. The impacts of concerns about contracting COVID-19 on the work-lives of AHPs, including dietitians, have been reported in studies globally [25, 44, 45]. For example, fear of contracting COVID-19 led some Canadian dietitians to relocate out of high-risk regions [25]. It was interesting to see that, despite the prevalence of COVID-19 related anxiety, only 4% of our respondents reported contracting COVID-19 at work. This may indicate that mandatory training in proper use of PPE was effective in preventing transmission of COVID-19 in healthcare settings.

Limited child care availability and school closures were also frequently reported by our respondents as reasons for lengthy absences from work; this aligns with the findings of other, related studies [1, 25]. In a study conducted pre-pandemic in the United States and Puerto Rico, Williams et al. [14] found that approximately 65% of RDs had care responsibilities, with 9% of those reporting care responsibilities for both dependent children and elders. It would be interesting to explore whether similar proportions of respondents in more gender-equal professions reported absences related to child care responsibilities. Gupta et al. [7] noted a gap in evidence relating to health professional absenteeism resulting from caregiving responsibilities in their systematic review of health workforce surge capacity during outbreaks of respiratory diseases. They hypothesized that this may be the result of a lack of consideration for sex and gender in existing research [7].

Redeployed healthcare staff during the COVID-19 pandemic were at greater risk of burnout and depression [46] and reported concerns related to the adequacy of training, patient safety, personal safety (e.g. concerns regarding access to PPE, exposure to COVID-19), heavy workload and work-life balance [23]. Rapid role reorganization can lead to job dissatisfaction if staff perceive that their skills are not being utilized or valued [21]. Clark et al.’s [36] recommendations to promote the well-being of redeployed healthcare staff, based on the findings of their systematic review of de-escalation strategies for redeployed staff in COVID-19 intensive care units, were to: provide redeployed staff with time off; monitor their long-term mental health, conduct debrief interviews post-redeployment, and to demonstrate respect and gratitude to redeployed staff as they return to their “home” departments/units/roles.

Coates et al. [1] identified attrition in the supply of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic as one of three key pressures on the health system. The findings of their scoping review of health workforce strategies in response to major health events indicate that increased supports are one way of alleviating this pressure. For example, the provision of child care services for employed healthcare staff. For the majority of studies included in the review, nurses and physicians were the professions of interest [1]. The development of flexible arrangements for staff has also been reported as a strategy to better ensure adequate staffing for surging needs in the intensive care setting [47]. More research is needed to better understand strategies that work best for other health professionals, such as AHPs [48].

The findings of this study can now be employed by health administrators and managers of RDs seeking to better prepare for a future pandemic (or a resurgence of COVID-19). It is clear that it is not ideal to redeploy the vast majority of the public health nutrition workforce for an extended time, particularly when redeploying into roles that may not draw on their specialized expertise and experience. To illustrate the potential consequences of an absent public health dietitian workforce, we can consider Type 2 diabetes. We know that rates of diabetes are increasing in Canada and that $30 billion CAD in costs are incurred to the health system in the treatment of diabetes [49]; costs which will only have been inflated [50] as those with type 2 diabetes were at higher risk of severe COVID-19 infections [51, 52]. The work of public health RDs, such as through support of the adoption of health-promoting agricultural and nutritional policies and modifications to infrastructure and environments that support nutritional health, contributes to the prevention of diabetes [53]. Thus, there are clear benefits to reducing the frequency, rate and duration of redeployment of public health dietitians in future public health emergencies: improved population health and related cost savings associated with those improvements and, increased odds of public health RD retention. As an alternative to redeploying public health RDs, health administrators can identify and build a pool of less specialized staff that can be called upon to fill roles held by public health RDs during the COVID-19 pandemic, including in call centres and contact tracing centres (e.g., students training to become health professionals [54]).

Additionally, to reduce lengthy absences from work among health professionals in a future pandemic(s), there will need to be: (i) more effective and/or timely communication of risk and of rates of healthcare workers contracting the infection [55, 56], and (ii) better provision for healthcare workers responsible for dependents, whether children or elders [1, 57].

5 Strengths and limitations

More than 200 dietitians completed our survey, with representation from RDs of varied ages, years as an RD, education levels, location of work, employment statuses, work settings and provinces/territories of residence. Unfortunately, data about the number of RDs working in each sector of dietetics are not available; we were unable to calculate how large our sample is in comparison to sector-specific RD workforce numbers. While there are enough similarities across the allied health professions to suspect similar results in other allied health professions working in diverse sectors (including clinical settings and public health or community settings), more research would be needed to determine the generalizability of our findings across the allied health professions.

Our data was collected in June of 2022, which is much further into the COVID-19 pandemic than most other studies exploring AHPs’ work experiences. Our survey was designed to capture the breadth and depth of RD experiences (e.g., knowing not only whether someone was redeployed but where, for how long, how many times, etc.). Both the absence of a significant body of research exploring RDs’ (or AHPs’ more generally) experiences during public health emergencies or during redeployment and our sample size of 205 (with only 67 redeployed RDs) precluded the testing of our findings against an accepted, existing model or overarching theory.

All data collected was self-reported. If, in a future study, it were possible to access and analyze data from administrative databases (e.g., internal databases recording absence timing/duration and details of training), then we may be able to establish the convergent validity of our findings. Our data were collected at a single time point, which for some may have been many months following their most recent redeployment. It is possible that this introduced recall bias. The survey was available in English only, offering it in French may have yielded greater participation from French-speaking RDs. While our process of identifying valid responses from “bot” responses was rigorous, the large volume of “bots” completing the survey may have had an impact on data quality. In future studies more steps will be taken at the survey administration step, such as by requiring reCAPTCHA completion before entering the survey, to limit “bot” activity.

6 Conclusions

Among Canadian, publicly-employed Registered Dietitians, the setting of their work had a significant impact on their experience of working through the COVID-19 pandemic. Public health dietitians were nearly all redeployed outside of their roles, with many seeing their typical work undone for many months. To prevent attrition of public health RDs, healthcare organizations should make dedicated efforts to give redeployed RDs the space, time and resources to effectively recover from potentially traumatic redeployment experiences, and should communicate widely their appreciation of and support for the “outputs” of the work of public health RDs. In future public health emergencies flexible staffing models and provision of child care for employed healthcare staff may help to improve the adequacy of staffing. Last, identifying and building a pool of less specialized staff that can be called upon to work in call centres and contract tracing centres during public health emergencies will help to ensure that specialized staff’s, including public health RDs’, energy is dedicated to work that draws on their specialized expertise and experience. More research is needed to better quantify the consequences of going without a public health nutrition workforce for an extended period of time and to understand the differential impact gender may have (or have had) on work experiences during a pandemic. Health administrators and managers of RDs will want to begin planning now. Specifically, they should aim to minimize the extent to which there are differential impacts of future pandemics on RDs of a specific gender or on those who are employed in a specific setting.

Data availability

Because participants did not give consent for the public posting of anonymized data, the dataset analysed during this study is not publicly available. The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PPE:

-

Personal protective equipment

- RD:

-

Registered Dietitian

- SDG:

-

Sustainable development goal

References

Coates A, Fuad A-O, Hodgson A, Bourgeault IL. Health workforce strategies in response to major health events: a rapid scoping review with lessons learned for the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Res Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00698-6.

Oliver TL, Shenkman R, Mensinger JL, Moore C, Diewald LK. A study of United States Registered Dietitian Nutritionists during COVID-19: from impact to adaptation. Nutrients. 2022;14:907.

Hitch D, Booth S, Wynter K, Said CM, Haines K, Rasmussen B, et al. Worsening general health and psychosocial wellbeing of Australian hospital allied health practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust Health Rev. 2023;47:124–30.

Holton S, Wynter K, Trueman M, Bruce S, Sweeney S, Crowe S, et al. Immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the work and personal lives of Australian hospital clinical staff. Aust Health Rev. 2021;45:656–66.

Lyttleton T, Zang E, Musick K. Parents’ work arrangements and gendered time use during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Marriage Fam. 2023;85:657–73.

Mo G, Cukier W, Atputharaja A, Boase MI, Hon H. Differential impacts during COVID-19 in Canada: a look at diverse individuals and their businesses. Can Public Policy. 2020;46:S26-71.

Gupta N, Balcom SA, Gulliver A, Witherspoon RL. Health workforce surge capacity during the COVID-19 pandemic and other global respiratory disease outbreaks: a systematic review of health system requirements and responses. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2021;36:26–41.

Lopez de Romaña D, Greig A, Thompson A, Arabi M. Successful delivery of nutrition programs and the sustainable development goals. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2021;70:97–107.

Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. https://s.un.org/2030agenda. Accessed 28 Apr 2024

Caswell MS. 2020 National Dietetic New Graduate Survey report. February, 2021. https://www.dietitians.ca/DietitiansOfCanada/media/Documents/Resources/New-Dietetic-Graduate-Survey-2020-(v-2).pdf?ext=.pdf . Accessed 20 Jan 24

Dietitians of Canada. The dietetic workforce in British Columbia: survey report. May, 2016. https://www.dietitians.ca/DietitiansOfCanada/media/Documents/Resources/2016-BC-Dietetic-Workforce-Survey-Report.pdf?ext=.pdf . Accessed 20 Jan 2024

Hewko SJ. Individual-level factors are significantly more predictive of employee innovativeness than job-specific or organizational-level factors: results from a quantitative study of health professionals. Health Serv Insights. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/11786329221080039.

da Costa Matos RA, de Almeida Akutsu RCC, Zandonadi RP, Botelho RBA. Quality of life prior and in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide cross-sectional study with Brazilian dietitians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052712.

Williams K, Eggett D, Patten EV. How work and family caregiving responsibilities interplay and affect registered dietitian nutritionists and their work: a national survey. PLoS ONE. 2021;16: e0248109.

Brunton C, Arensberg MB, Drawert S, Badaracco C, Everett W, McCauley SM. Perspective of registered dietitian nutritionists on adoption of telehealth for nutrition care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare. 2021;9:235.

Naja F, Radwan H, Ismail LC, Hashim M, Rida WH, Qiyas SA, et al. Practices and resilience of dieticians during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey in the United Arab Emirates. Hum Res Health. 2021;19:141.

Donnelly R, Keller H. Challenges providing nutrition care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Canadian dietitian perspectives. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:710–1.

Rozga M, Handu D, Kelley K, Jimenez EY, Martin H, Schofield M, et al. Telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey of registered dietitian nutritionists. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;121:2524–35.

van Oorsouw R, Oerlemans A, Klooster E, van den Berg M, Kalf J, Vermeulen H, et al. A sense of being needed: a phenomenological analysis of hospital-based rehabilitation professionals’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Phys Therapy. 2022;102:pzac052.

da Costa Matos RA, de Almeida Akutsu RCC, Zandonadi RP, Rocha A, Assunça Botelho RB. Wellbeing and work before and during the SARS-COV2 pandemic: a Brazilian nationwide study among dietitians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5541.

Walker K, Gerakios F. Redeployment during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for a clinical research workforce. Br J Nurs. 2021;30:734–41.

Government of Canada. Deployment. April 2, 2007 https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/staffing/public-service-workforce/deployment.html . Accessed 18 Sept 20

Evans S, Shaw N, Veitch R, Layton M. Making a meaningful difference through collaboration: the experiences of healthcare staff redeployed to a contact tracing team as part of the COVID-19 response. J Interprof Care. 2023;37:383–91.

Panda N, Sinyard R, Henrich N, Cauley C, Hannenberg A, Sonnay Y, et al. Redeployment of health care workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study of health systems leaders’ strategies. J Patient Saf. 2021;17:256–63.

Caswell MS, Lieffers JR, Wojcik J, Eisenbraun C, Buccino J, Hanning RM. COVID-19 pandemic effects on job search and employment of graduates (2015–2020) of Canadian dietetic programmes. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3148/cjdpr-2023-004.

Handu D, Moloney L, Rozga M, Cheng FW. Malnutrition care during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for registered dietitians nutritionists. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;23:979–87.

Tardif A, Gupta B, McNeely L, Feeney W. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health workforce in Canada. Healthc Q. 2022;25:17–20.

Rutty C. COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2023. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/covid-19-pandemic . Accessed 31 Jul 2023

Teitcher JEF, Bockting WO, Bauermeister JA, Hoefer CJ, Miner MH, Klitzman RL. Detecting, preventing, and responding to “fraudsters” in internet research: ethics and tradeoffs. J Law Med Ethics. 2015;43:116–33.

Griffin M, Martino RJ, LoSchiavo C, Comer-Carruthers C, Krause KD, Stults CB, et al. Ensuring survey research data integrity in the era of internet bots. Qual Quant. 2022;56:2841–52.

Leiner D. Too fast, too straight, too weird: non-reactive indicators for meaningless data in internet surveys. Surv Res Methods. 2019;13:229–48.

Bruening M, Perkins S, Udarbe A. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Revised 2022 standards of practice and standards of professional practice for registered dietitian nutritionists (competent, proficient, and expert) in public health and community nutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2022;2022(122):1744–63.

World Health Organization: Food systems for health: information brief. 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1398601/retrieve . Accessed 31 Jul 2023.

Hewko SJ, Oyesegun A, Clow S, VanLeeuwen C. High turnover in clinical dietetics: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:25.

Loan-Clarke J, Arnold J, Coombs C, Hartley R. Retention, turnover and return—a longitudinal study of allied health professionals in Britain. Hum Res Manag J. 2010;20:391–406.

Clark SE, Chisnall G, Vindrola-Padros C. A systematic review of de-escalation strategies for redeployed staff and repurposed facilities in COVID-19 intensive care units (ICUs) during the pandemic. eClinicalMedicine. 2022;44: 101386.

Liberati E, Richards N, Scott D, Boydell N, Parker J, Pinfold V, et al. A qualitative study of experiences of NHS mental healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:250.

Anxiety Canada. Helping health care workers cope with COVID-19 related trauma. n.d. https://www.anxietycanada.com/articles/helping-health-care-workers-cope-with-covid-19-related-trauma/ . Accessed 18 Jul 2023

Gaughan AA, Walker DM, DePuccio MJ, MacEwan SR, McAlearney AS. Rewarding and recognizing frontline staff for success in infection prevention. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49:123–5.

Gess E, Manojlovich M, Warner S. An evidence-based protocol for nurse retention. J Nurs Adm. 2008;38:441–7.

Robertson MB. Hindsight is 2020: identifying missed leadership opportunities to reduce employee turnover intention amid the COVID-19 shutdown. Strateg HR Rev. 2021;20:215–20.

Canadian Academy of Health Sciences. Canada’s health workforce: pathways forward. 2023. https://cahs-acss.ca/assessment-on-health-human-resources-hhr/ . Accessed 19 Jul 2023

European Federation of the Associations of Dietitians. The role of European public health dietitians: EFAD briefing paper. 2012. https://www.efad.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/briefing_paper_on_role_of_european_ph_dietitian.pdf . Accessed 18 Jul 2023

Wynter K, Holton S, Trueman M, Bruce S, Sweeney S, Crowe S, et al. Hospital clinicians’ psychosocial well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal study. Occup Med. 2022;72:215–24.

Coto J, Restrepo A, Cejas I, Prentiss S. The impact of COVID-19 on allied health professions. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0241328.

Dennings M, Goh ET, Tan B, Kanneganti A, Almonte M, Scott A, et al. Determinants of burnout and other aspects of psychological well-being in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16: e0238666.

San Juan NV, Clark SE, Camilleri M, Jeans JP, Monkhouse A, Chisnall G, et al. Training and redeployment of healthcare workers to intensive care units (ICUs) during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12: e050038.

Orhierhor M, Pringle W, Halperin D, Parsons J, Halperin SA, Bettinger JA. Lessons learned from the experiences and prospectives of frontline healthcare workers on the COVID-19 response: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10062-0.

Diabetes Canada. Diabetes rates continue to climb in Canada. Mar 3, 2022. https://www.diabetes.ca/media-room/press-releases/diabetes-rates-continue-to-climb-in-canada . Accessed 20 Jan 2024

Bain SC, Czernichow S, Bøgelund M, Madsen ME, Yssing C, McMillan AC, et al. Costs of COVID-19 pandemic associated with diabetes in Europe: a health care cost model. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(1):27–36.

Butler MJ, Barrientos R. The impact of nutrition on COVID-19 susceptibility and long-term consequences. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:53–4.

James PT, Ali Z, Armitage AE, Bonell A, Cerami C, Drakesmith H, et al. The role of nutrition in COVID-19 susceptibility and severity of disease: a systematic review. J Nutr. 2021;151:1854–78.

Bergman M, Buyssschaert M, Schwarz PE, Albright A, Narayan KV, Yach D. Diabetes prevention: global health policy and perspectives from the ground. Diabetes Manag. 2015;2:309–21.

Koetter P, Pelton M, Gonzalo J, Du P, Exten C, Bogale K, et al. Implementation and process of a COVID-19 contact tracing initiative: leveraging health professional students to extend the workforce during a pandemic. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:1451–6.

Mushi A, Yassin Y, Khan A, Yezli S, Almusaini Y. Knowledge, attitude, and perceived risks towards COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of risk communication messages on healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2022;14:2811–24.

Wilbiks JMP, Best LA, Law MA, Roach SP. Evaluating the mental health and well-being of Canadian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak. Healthc Manag Forum. 2021;34:205–10.

Wickner P, Hartley T, Salmasian J, Sivashanker K, Rhee C, Fiumara K, et al. Communication with health care workers regarding health care-associated exposure to Coronavirus 2019: a checklist to facilitate disclosure. J Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2020;46:477–82.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded through an internal University of Prince Edward Island research grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H. conceived of the project, secured the funding and drafted the survey tool. S.H. conducted the descriptive analysis of the quantitative survey data and wrote the first complete draft and the revisions for this manuscript. J.F. provided substantive feedback on all parts of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed for adherence to ethical guidelines for human subjects by the UPEI Research Ethics Board (#6011592). All participants reviewed an information letter prior to entering the survey and were informed that by clicking “next” to begin the survey, they were providing informed consent to participate in the study. All participants were over the age of 18. This research was performed in-line with the precepts of the Tri-Council Policy Statement 2: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (2022).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hewko, S.J., Freeburn, J. The work-lives of Canadian Registered Dietitians during the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive analysis of survey data. Discov Health Systems 3, 54 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00124-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00124-3