Abstract

Background

Lower-level private-for-profit urban immunization service providers contribute immensely to service delivery and data generation which informs evidence-based planning for the delivery of equitable immunization services within the urban context. And yet, current efforts tend to over-concentrate on supporting the public health sector. We conducted this implementation research study in a bid to contribute to improvements in the accuracy and timeliness of immunization service data among lower-level private-for-profit immunization service providers within Kampala Capital City of Uganda.

Methods

A quasi-experimental design was adopted with a participatory process leading to the identification of two poor-performing city divisions where the intervention was implemented. Forty private health facilities participated in the implementation research with 20 assigned to the intervention while the other 20 were assigned to the control. Performance measurements were assessed at baseline and end-line to compare outcomes between the intervention and control groups.

Results

Through a theory-driven design with the COM-B as the guiding model, the behavioural change intervention functions targeted to cause the desired change leading to improvements in data quality among private providers were; (1) training, (2) modelling, (3) persuasion, (4) education, (5) environmental restructuring, (6) enablement and (7) coercion. In combination, they were primed to contribute to improvements in skills and approaches to data handling while maintaining of a close oversight function.

Conclusions

The applied intervention components were preferred for their contextual applicability within the urban private immunization service delivery settings with a likelihood of sustaining the gains for some time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Immunization remains the most cost-effective, high-impact public health intervention in averting vaccine-preventable diseases while holding multiple benefits including opportunities for complementation of primary healthcare which is crucial for health system functioning. The “Decade of Vaccines” duration ran from 2010–2019 with concerted efforts to improve immunization coverage [1, 2]. Globally, greater strides have seen Diphtheria, Pertussis and Tetanus (DPT3) coverage increase to 86% from 72% in 2000 and 20% in 1980. For the first time, the world is closer to eliminating polio with measles registering a decline of 80% related mortality translating into over 21 million deaths averted [3, 4]. Maternal and neonatal tetanus is eliminated in the world except for 13 countries as of March 2019 [5, 6].

Quality immunization service delivery relies on the availability of accurate, complete and timely data to inform evidence-based decision-making [7, 8]. Country-level efforts have seen interventions targeted at improving immunization data quality spearheaded by the Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI) and the Ministry of Health (MoH) [9,10,11]. This has seen a migration from paper-based Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) records to electronic District Health Information Systems (DHIS2) [12, 13].

Delivery of immunization services within an urban context is predominantly by private-for-profit service providers and follows the urban market demand and supply forces [14, 15]. Lower-level private providers tend to establish in densely populated suburbs located in informal settlements [16, 17]. The supervision arrangements by the city authorities are complex often manifesting in the form of regulation due to presence of unlicensed entities which operate under the radar taking advantage of the challenges within the current supervision structures [18]. Lower-level private-for-profit service providers continue to operate amidst limited resources constraining their abilities to invest in sound data systems due to competing priorities for the direct revenue inflow [19, 20]. Due to the prevailing environmental context, the urban dwellers residing in informal settlements are more vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases [21].

The provision of immunization services by lower-level private-for-profit providers faces unique challenges which extend into the quality of data generated and timeliness of submission [22]. First, it is designed to be free of charge with many motivated into its provision due to the potential to attract clientele seeking complementary services offered at a fee [23]. Nonetheless, they incur costs to ensure continuity of service delivery in terms of running costs such as salaries. To some lower-level private immunization services providers, the quality of data maybe less prioritized with data systems within the private sector not necessarily compatible with DHIS2. Prioritization of data quality improvement efforts is often met with more competing priorities, especially service improvements with the potential to bring in direct revenue. Still, urban immunization service providers are faced with a high staff turnover which impedes skills retention, and a lack of a direct incentive for data quality improvement among others. Hence, we conducted this implementation research to improve the accuracy and timeliness of immunization service data among lower-level private-for-profit immunization service providers within Kampala Capital City of Uganda.

1.1 Research questions

-

1.

What are the challenges impeding the delivery of quality and timely immunization service data among private providers?

-

2.

How can solutions be co-created to respond to these challenges

-

3.

Can co-created intervention be piloted among private providers aimed at improving the quality and timeliness of immunization data.

-

4.

What are the process experiences and best practices, which can be replicated from this learning?

Results for objectives 1, 2 and 4 have been submitted for publication elsewhere and currently under review. This paper specifically focuses on documenting the implementation processes and experiences of piloting the co-created intervention among the lower-level private-for-profit immunization service providers within Kampala Capital City Authority which was the focus of objective 3 of this implementation research.

2 Methods

2.1 Study setting

This implementation research was conducted in Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA). Two city administrative divisions (Kawempe and Makindye) were selected as study sites.

2.2 Study design

The implementation research adopted a quasi-experimental mixed method before and after study approach to address gaps in immunization data quality among lower-level private-for-profit providers within Kampala city. We adopted a human-centred design to develop the intervention in a participatory manner together with the urban immunization stakeholders. In this pursuit, the intervention arm was developed following theoretical guidance from the Behavioural Change Wheel (BCW) as the overall theoretical anchor [24] and later the Theoretical Framework for Acceptability (TFA) which facilitated theory-informed approaches to promote acceptability and rollout of the co-designed intervention [25, 26].

2.3 Behavioural change wheel (BCW)

The Behavioural Change Wheel (BCW) is a framework developed to specifically guide the systematic analysis of the underlying problems, it uses the synthesised information to design interventions that respond directly to identified challenges to bring about the desired change [24]. Each of the intervention functions of the BCW were then translated for application to the project related required capacities necessary to cause change as reflected in Table 1 below. COM-B facilitates appreciative inquiry around the contextual factors likely to influence intervention success and outcomes [27].

2.4 Step 1: Baseline data collection

To understand the magnitude and nature of the problem, secondary data analysis to reveal the performance of immunization data quality across the city divisions was conducted. This was complemented with qualitative baseline interviews conducted to explore the likely challenge contributing to the observed performance to provide a basis for designing solutions. Preliminary analysis of this baseline data highlighted some of the implementation gaps in immunization data capture. For the quantitative data, a decision was then taken to set the division as the unit of analysis. Following consultations with the KCCA team, two divisions were selected based on the performance of selected immunization data quality indicators according to the Reach Every District (RED) categorisation. The base period was set at the first and second quarter of 2021 (January-June) which coincided with the immediate period before the commencement of this implementation research. Overall, results revealed that the Makindye and Nakawa divisions performed slightly poorly compared to the other divisions as reflected by the colour codes in Fig. 1 below. However, contextually Nakawa as an industrial division of the city had more “visitors” utilising immunization services provided who resided outside the city. It was then agreed that the particular division be replaced with Kawempe division which followed in poor performance and had a bulk of service users residing within the capital city. Performance above 100% in this context would be explained by the many service users residing outside the city and yet planning was done based on the resident population only.

2.5 Step 2: Intervention design and implementation

Participatory methodologies were adopted to agree on an appropriate intervention that would respond to identified underlying bottlenecks. The COM-B model focusing on the middle layer was used to link intervention functions in response to particular bottlenecks [28]. It represents Capability (C), Opportunity (O), Motivation (M) and Behaviour (B). The model postulates that these three aspects influence behaviours that are responsible for all factors outside the individual’s attributes that make the behaviour possible. The COM-B model was specifically preferred because it facilitated the understanding of behaviours and argues that both Capability and Opportunity have a direct influence on motivation [34]. Therefore, in order to effect positive changes in the desired behaviours and in this study which was the accurate recording and timely submission of immunization data from service providers, both Capabilities and opportunities had to be targeted [33]. The study therefore relied on the COM-B model to identify the underlying challenges and align them to the possible interventions to address those challenges.

2.6 Identifying interventions to respond to gaps

Two activities were performed to steer consensus on key interventions to address the identified gaps. The first activity involved the study team analysing baseline qualitative data to identify gaps and propose possible interventions to address the gaps. Thereafter, stakeholders were convened in a co-creation workshop where they were presented with synthesised qualitative results highlighting the gaps.

2.7 Co-creation of intervention strategies and implementation

Following recommendations from the co-creation workshop, the study team went back to align recommendations to the identified challenges. These were then presented as intervention packages to staff from intervention private-for-profit health facilities during a workshop which was organised as an inception meeting for the intervention. Health facility immunization services focal persons who were earlier identified were specifically targeted for the meeting. After the presentation, feedback and intervention refinement were elicited regarding the contextual factors likely to favour/hinder the smooth implementation. These consisted of Behavioural Change Techniques (BCT) likely to alter the behaviours of health workers delivering immunization services among participating private immunization services providers. The proposed interventions were aligned to the middle layer of the Behavioural Change Wheel (BCW) as reflected in Fig. 2 below [27, 28]. They were translated into the Theoretical framework for acceptability (TFA) in response to challenges associated with the local translation of theoretically derived interventions that would not have been compatible with the local context. It was aimed at gaining consensus on the practices that service providers would adopt into their work routine to cause improvements in data quality and timely submission.

2.8 Assignment to the study arms

The health facilities included in the study had to be legally registered, operated by licensed providers and at the time delivering immunization services in the two selected city divisions. These were matched based on service volumes considering the average number of clients that received vaccination services from the facilities. Ten facilities from each of the divisions were then assigned to the intervention and an equal number was assigned to the control arm bringing the total to twenty facilities for each of the study arms. The assignment to either arm of the intervention was done by the study team members in the absence of the city health managers and health workers who were familiar with the facilities to limit bias. Facilities assigned to the intervention arm received the intervention package on top of the standard routine support while facilities assigned to the control arm continued with the routine support.

2.9 Step 3: Intervention effect assessments

The urban immunization data improvement project through the lower-level private-for-profit provider involvement had results assessed at the division level; health facility level and individual assessments of behaviour change towards adoption of practices that promoted accurate recording and timely submission of immunization data. It was integrated within the routine immunization services with the division EPI teams providing supervision and oversight. Quantitative data assessments were conducted at baseline and end line while monthly monitoring for timely submissions was carried out during the implementation process. Assessment of management behaviour change due to intervention effect was conducted using qualitative methods before and after intervention implementation. The key outcome measures were; the accurate and timely submission of data as assessed below;

-

1.

Accurate submission of immunization data from the private providers was assessed by computing monthly monitoring data using five proxy indicators at the health facility level; (1) Polio 1 and (2) DpT + HepB + Hib1, (3) DpT + HepB + Hib3, (4) Measles and (5) Fully Immunized. It was expected that the aggregated total for each of the antigens would tally to reflect completion rates. It was entered in the DHIS2 with a hard copy paper version delivered to the division EPI focal person.

-

2.

Timely submission of data was assessed based on the date the data was submitted into the DHIS2 system. All facilities were familiar with the timelines within which to submit the monthly immunization returns. Our team retrieved this data one week after the expected last day of submission. Each facility's return was computed to establish the percentage of submissions from the expected monthly submissions.

2.10 Roles of the different study team members

The study was planned and implemented by researchers from Makerere University School of Public Health (ES and ER). Together with the support of the data collectors who collected the baseline data, analysed it and disseminated results. They in addition provided training and capacity building for the implementation team, facilitated the co-creation workshop, collected and analysed monitoring data. The technical implementation team of Kampala Capital City Authority (PK, YK, and SZK). These provided technical support supervision and monitoring of logistics essential to effective documentation and submission of immunization data during the implementation of the study. The decisions for the intervention design and final implementation package were jointly made by the research team, the technical team from KCCA and the urban lower-level private-for-profit immunization service providers during the co-creation workshop.

3 Results

The implementation research intended to lead to a change in management and practice behaviours at the intervention functions. It specifically targeted individual-level actions from where the health workers’ capacity enhancement, service delivery improvement and strengthening the oversight functions were prioritised. This was realised during the co-creation workshop whose outcome was to arrive at the proposed solutions to respond to the identified gaps. Proposed interventions were later aligned to the inner circle of the applied framework (COM-B) [29]. The capability aspect of the framework targeted behavioural change focusing on health workers’ skills and knowledge to improve immunization data quality while the opportunities aimed at targeting interventions that improved the work environment affecting data quality. Motivation on the other hand aimed at changing health worker practices which impeded data quality and promoting reflexive processes for them to develop a positive attitude towards quality data generation. Table 2 below presents the detailed assignment of proposed interventions to the inner circle of the applied framework (COM-B).

Having assigned the proposed interventions to the three high-level influences on behaviour (capabilities, opportunities, motivation), the next step involved mapping the same onto the middle circle of the BCW which targets the intervention functions. Detailed illustration of each of the proposed interventions alongside the intervention functions follows;

4 Capacity building

The capacity to deliver immunization services is desirable when the available health workers have the required skills to deliver such services. According to the intervention function targeting health worker capacity enhancement, the options undertaken under this implementation research were education, persuasion, training, modelling behaviours, and enablement.

4.1 Training of health workers

Health facilities were introduced to the training package targeting facility-focal persons directly involved in the delivery of immunization services. They were aimed at imparting skills relevant to quality data management. The strategy was responding directly to the inadequate data management skills among lower-level private-for-profit facility health workers. Two rounds of training were conducted to impart data quality-related skills and took the form of an offsite workshop arrangement. Different pedagogical approaches were applied such as facilitator delivery where the facilitator delivered material on specific topics with participants allowed to seek clarification where appropriate. The brainstorming approaches had participants requested to share experiences and challenges of completing the tools where upon sharing, they contributed to strategies for addressing the identified challenges. Of particular emphasis, was the need to address health worker-related behaviours that affected data quality and timeliness. The training was followed by site visits health workers were encouraged to always complete all entries on the same day the service was delivered and have them submitted on time. Supervisors provided their telephone contacts for the health workers to engage and inquire in case any clarifications were required. The content of the training included taking participants through the requirements for private-for-profit service providers to deliver immunization services in Kampala. It also covered the supervisory relationships between the private providers and the city authorities. All data tools associated with the delivery of immunization services were re-introduced to the participants and guided on how to complete them and eventual submission at the different time points and recipient entities.

4.2 Roll out of Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)

Persuasion and modelling of health worker behaviour were conducted as part of immunization service delivery but mainly in public facilities supported by the City health managers. This was cascaded to private providers other than introducing completely new CQI approaches. It was aimed at providing the private sector health workers with an example of quality immunization data for them to aspire to achieve. It also served to demonstrate to them in a one-to-one interface how best to collect accurate data and submit it on time. At the centre of implementation was the field supervision team which comprised the division EPI focal persons, the Biostatisticians and the HMIS officers stationed at the implementing divisions. Three tools were used; (1) the adapted data quality improvement tool to suit project objectives, (2) the supervision log and (3) the qualitative support supervision checklist.

The identified proxy indicator for quality improvement was measles since it was administered at one year. It was presumed that by that time; all the other antigens would have been administered and hence fully vaccinated and ought to be reflected in the data. The hierarchical data structure which informed the components of Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) were; (1) child register, (2) tally sheet, (3) HMIS form 105 hardcopies, (4) DHIS2 and (5) total measles according to the Vaccine Injection Materials Control Book (VIMCB). The field teams practically demonstrated EPI data quality improvement strategies and innovative approaches at the health facility level. The areas for improvement were documented in the facility supervision log/ records and shared through the facility end-of-supervision visit feedback meetings for health workers to internalize.

The field supervision teams assessed the level of agreement between the data registered at different levels of the hierarchical structure of data submission. The overall analysis of this data revealed persistent common challenges included; (a) not updating the child register, (b) not updating the VIMCB, (c) missing tally sheets and (d) no extracts made from HMIS form 105. The most common initiatives done well included; the presence of standardised HMIS tools, availability of staff to at least provide immunization services and compile immunization data, a compilation of monthly HMIS reports in some facilities, submission of monthly data to the division EPI focal person and archiving of child register and tally sheets. The common recommendations were; updating of child register and VIMCB, quantification of expected HMIS tools stock, provision of support to the facility to compile and submit data through DHIS2 and updating child registers as well as improvements in archiving of immunization data records.

4.3 Generating interest in the utility of immunization data at the facility level

Persuasion and training were conducted to ignite the desire among health workers to use the immunization data generated at the facility level. A combination of intervention function approaches with private sector health workers was implemented to stimulate action and induce positive feelings about data quality and its utility at the facility level. It was embedded within their everyday activities at the facility to monitor performance and its implication for service delivery. Education during the mentorship sessions increased knowledge and understanding of immunization data, quality requirements and the steps to undertake to achieve the desired quality. This made the private facility owners and health workers appreciate the importance of generating and submitting quality data. Facilities were mentored to develop simple graphs to reflect the facility's performance but also identify data gaps from which they would devise solutions to respond to the identified gaps.

Records retrieval as a barrier to data quality was addressed through the initiation of a cohort system of registration within the facility immunization registers following birth months among facilities that had not yet adopted such practices. Intervention function approaches like persuasion and training were adopted to this end. Details of the application are presented in Table 3 below;

5 Service delivery improvements

The nature of immunization service delivery among lower-level private-for-profit immunization service providers also called for service delivery improvements to generate a positive effect on data quality. Intervention options adopted that targeted service delivery improvements to enhance data quality mainly responded to environmental restructuring, modelling behaviour, training and persuasion.

5.1 Ensuring a constant supply of vaccines and data tools.

Environmental restructuring and modelling of health worker behaviours saw efforts to ensure the smooth delivery of supplies required for the delivery of immunization services among private providers. At the planning level, this activity targeted responding to all barriers impeding the effective provision of immunization services with direct negative effects on data quality. Later, it was scaled down only to cover data aspects after it emerged that the supply of hard copy HMIS tools went on smoothly. Also, the availability and delivery of vaccines from the Kampala Capital City Authorities did not have many challenges as cases of stockouts were irregular. The biggest challenge was found with the private providers finding difficulty in accounting for dispensed vaccines before replenishments. Specifically, they were required to submit an updated (1) tally sheet and (2), Vaccine Injection Materials Control Book (VIMCB). Together, these would reflect previous vaccines received and utilisation rates which all had to reflect similarities before receiving new vaccine stock. Unreconciled records would attract first; the extra task of rectifying the errors before clearance for receipt of new vaccine stock. This in turn would cause delays at affected private facilities before the next stock of vaccines would be released. Enforcement of this requirement was strengthened among intervention arm private providers with a standard routine followed for private providers in the control arm. The message, telephone calls and onsite supervision visit reminders were specifically enforced to achieve this objective. Capacity building was tailored to address these challenges to improve service delivery which would translate into quality and timely immunization data.

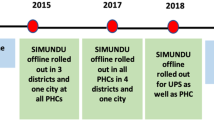

5.2 Admission of private providers onto the DHIS2 platform

Training and education intervention functions were used to support private providers in submitting their data timely. Facilities that initially submitted their immunization data through supervising public facilities found it hard to monitor the progress of data improvement efforts. Those assessed to have the capacity to submit their data directly into the DHIS2 without having to go through the supervising public facilities were identified. The capacities referred to included; the presence of cold chain, computer literacy and availability of a computer/internet connection onsite. They were then supported and mentored to have their data entered directly and thereafter looped into the DHIS2. This would address the previous challenge of double entry/recording and incomplete data submission which were associated with compromised data quality.

6 Active oversight function strengthening

Maintaining close oversight among the private providers ensure that the acquired skills and service delivery improvements would result in quality immunization data. The intervention functions adopted to ensure this was realised included; training, modelling behaviour, persuasion, enablement and restriction to promptly identify gaps and enforce adherence to data submission timelines. They are explained in detail below;

6.1 Monitoring and supportive supervision

To enhance group power through peer support, private providers were organised into a Whatsapp group (an online encrypted digital messaging platform) from where they would share challenges and how they addressed them amongst peers. The supervision team (City EPI focal persons, Division data personnel and study team members) was also added to this platform. They would share insights observed from the submitted data and requested for clarification from particular facilities which guided the content of the feedback. Similarly, service providers in the intervention facilities would also use the same platform for peer learning. This mode of information exchange was on top of the routine support supervision visits.

6.2 On-spot checks and enforcement of submission timelines.

A combination of training and modelling health worker behavioural approaches were employed. These approached included; ensuring that the private actors complied with set requirements for immunization data quality. During the implementation processes, challenges identified as unique to specific private facilities elicited tailor-made solution identification factoring in the context. One such challenge was the inability of private immunization service providers to update the immunization registers after completing the immunization tally sheets. The latter monitors vaccine consumption and is required for submission to receive vaccines. Failure of which facilities are not replenished with vaccine stock until corrections were made to identify errors. The former was only submitted to capture immunization service coverage. Through spot checks, facilities were supported to identify these unique challenges and later requested to submit the required data.

The practice before the rollout of the implementation study was that all facilities were mandated to submit their monthly immunization data by the 7th of every month so that it was compiled by the data team together with the division EPI focal person for submission into the DHIS2 by the 15th of that very month. However, this was more pronounced among the public providers with whom they had a lot of control. Although it was the same practice that was required to apply for the private immunization providers, systems challenge such as supervision lapses private facilities volumes made it a persistent challenge. For private providers in the intervention arm, this was strictly enforced through restriction and coercive means as one of the measures complemented by timely reminders and the requirement to comply to improve their facilities’ immunization data quality and timely reporting. The reminders took the form of short message systems (SMS) reminders and/or call-backs and sometimes would culminate into physical inspection to establish the challenges.

7 Discussion

This paper describes the processes undertaken to co-design and roll out an implementation research project aimed at improving the accurate recording and timely submission of immunization service data among urban lower-level private-for-profit immunization service providers within Kampala Capital City of Uganda. The participatory approach resulted in co-creating interventions targeting modification of health workers' and health managers' behaviors towards practices that promoted accurate and timely immunization data at the private health facility level. The consensus was built on three broad strategies which include; health worker capacity building, service delivery improvements and active oversight function. When mapped first along the behavior influence, they reflect capabilities, opportunities and motivation. When aligned next to the intervention function, they reflect; (1) Environmental restructuring, (2) education, (3) persuasion, (4) training, (5) modelling, (6) enablement, (7) restriction, (8) incentivization and or (9) coercion. These particular interventions included; (1) Targeted training, (2) modelling through continuous Quality Improvements, (3) persuasion through onsite mentorships, and enhanced monitoring and support supervision, (4) coercion through onsite spot checks, enforced supply of vaccines upon data accountability and enforced timely submission of data, as well as (5) environmental restructuring through support which ensured availability of data tools, and vaccines.

7.1 Training of health workers

The first intervention function that was targeted according to the Behavioural Change Wheel (BCW) was education through off-station pieces of training as a capacity-building approach [30]. This considered the timing of training to respond to staff turnover and content delivered which resonated well to accommodate refresher content for in-service staff and introductory material for new staff. Training is an important capacity-building approach that improves the physical and psychological capacities of individuals [31]. Specifically, capacity building through focus group training has been observed as an important participatory research approach with a high potential for success and sustainability [29]. It is also common in sub-Saharan Africa settings where it has been applied in fostering research capacities [32]. The training was augmented with site visits and follow-up communication exchanges between health workers and supervisors. Within the context of urban immunization service provision, adopting the training approach was appropriate as it enabled the delivery of content within a physical setting where participants were presented with the option of seeking clarification. It also responded to the need among private providers where high rates of staff turnovers left the facilities with previously acquired skills and a vicious cycle of re-skilling. Whereas it may not address all specific needs of each facility, it remains an acceptable avenue for delivering generic content related to data quality and timely submission.

7.2 Roll out of Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)

This was in response to the challenges that private providers often missed out on routine practices conducted in public facilities. Sometimes it came about due to inadequate resources which impeded the inclusion of private providers in many of these initiatives. The benefits of continuous quality improvements in immunization services, in general, have previously been documented in almost all spheres of health service provision [7]. The same has the potential of improving immunization data quality among urban private providers [33, 34]. It is therefore recommended that deliberate efforts followed by adequate resource allocation are dedicated to enabling the CQI among urban private providers to improve the quality and timeliness of immunization data.

7.3 Generating interest in the utility of immunization data at the facility level

The onsite mentorships were intended to promote data utility and appreciation as a motivation to generate quality data. It was aimed at addressing implementation contextual factors that impeded the generation of accurate and timely submission of data. Sometimes, the best way to ascertain whether providers were practising what they learned was through onsite mentorships. In the absence of motivating incentives to improve, participatory approaches have been found to trigger the needed motivation to act. In our context, the site mentorships were participatory first by seeking to know the underlying reasons and then later working collaboratively to address the problem. This finding compares well with similar results from Ethiopia which adopted community engagement approaches through data verification to steer motivation towards the use of routine data for decision-making [8]. Onsite mentorship enables tailoring of support to the context which remains true even for motivation factors [35]. Context has previously been attributed to several variations in the quality of administrative vaccination data in Uganda [11]. Increasing the intensity of onsite mentorships perhaps can go a long way in addressing context-specific challenges that may be impeding data appreciation and utility at most of the private immunization service providers. Once addressed, it can go a long way in ensuring that quality and timely data is generated and transmitted. Future endeavours therefore ought to consider mechanisms of ensuring intensified onsite mentorships for private providers amidst scarcity of resources and human resource constraints inherent within the supervision functions.

7.4 On-spot checks and enforcing submission timelines

The practice of locking out facilities from the submission systems past the due date was reinforced among facilities within the intervention arm. Private providers are sometimes only known to comply with strict regulations which attract actions likely to affect their revenue generation such as the closure of premises. Requirements such as blocking out the submission portal when entries were made beyond the submission deadlines were likely to be violated since the repercussions for deviations were not in confrontation with their revenue generation aspirations. Such service delivery misalignments have previously contributed to incomplete immunization coverage [36]. Also, deliberately instituting mandates to address vaccination challenges has been reported elsewhere with mixed results [37]. Adopting mixed practices known to be effective among public providers in compelling them to adhere to service delivery standards is ideal as well for private providers since it may enhance the standardisation of requirements for both public and private providers.

8 Limitations

The first limitation of the study was the short implementation duration. The heterogeneity added from all different facilities personnel, high staff turnover, different standard operating procedures from different health facilities were the other potential limitations. Lastly, the study was conducted among forty lower-level private-for-profit health facilities which may be perceived as a small sample to draw generalisation across the entire lower-level private-for-profit health facilities. The generalisability and transferability of these results are highly dependent on the implementation context. Hence caution is advised while interpreting these results.

9 Conclusion

The participatory practice of ensuring quality data and timely reporting among private-for-profit immunization services providers within an urban setting was noted to be minimal. This was partly explained by contextual factors such as high staff turnover but also the low appreciation of data quality improvement efforts which do not necessarily translate into direct revenues for the private actors. Establishing these barriers and collaboratively working with private-for-profit immunization service providers to address the problem-initiated efforts and interests to improve the immunization data quality is paramount. Participatory approaches were found to be effective in addressing this gap. Strengthening the health worker capacities, service delivery improvements and playing an active oversight function to the private providers were found to be a step in the right direction towards responding to the complex challenges impeding quality immunization data among lower-level private-for-profit urban immunization service providers in Kampala Capital City of Uganda.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are included within this submission.

References

Ozawa S, Stack ML, Bishai DM, Mirelman A, Friberg IK, Niessen L, et al. During the ‘decade of vaccines’,the lives of 6.4 million children valued at $231 billion could be saved. Health Affairs. 2011;30(6):1010–20.

Moxon ER, Siegrist C-A. The next decade of vaccines: societal and scientific challenges. Lancet. 2011;378(9788):348–59.

Mosser JF, Gagne-Maynard W, Rao PC, Osgood-Zimmerman A, Fullman N, Graetz N, et al. Mapping diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus vaccine coverage in Africa, 2000–2016: a spatial and temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1843–55.

Burgess CA. Implementing revised RED approaches to immunize in an evolving African landscape. Pan Afr Med J. 2017. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.supp.2017.27.3.11627.

Khan R, Vandelaer J, Yakubu A, Raza AA, Zulu F. Maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination: from protecting women and newborns to protecting all. Int J Women Health. 2015;7:171.

Organization WH. Protecting all against tetanus: guide to sustaining maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination (MNTE) and broadening tetanus protection for all populations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Manyazewal T, Mekonnen A, Demelew T, Mengestu S, Abdu Y, Mammo D, et al. Improving immunization capacity in Ethiopia through continuous quality improvement interventions: a prospective quasi-experimental study. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(06):35–48.

Tilahun B, Teklu A, Mancuso A, Endehabtu BF, Gashu KD, Mekonnen ZA. Using health data for decision-making at each level of the health system to achieve universal health coverage in Ethiopia: the case of an immunization programme in a low-resource setting. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19(2):1–8.

Mukanga DO, Kiguli S. Factors affecting the retention and use of child health cards in a slum community in Kampala, Uganda, 2005. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(6):545–52.

Nsubuga F, Luzze H, Ampeire I, Kasasa S, Toliva OB, Riolexus AA. Factors that affect immunization data quality in Kabarole district, Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9): e0203747.

Ward K, Mugenyi K, MacNeil A, Luzze H, Kyozira C, Kisakye A, et al. Financial cost analysis of a strategy to improve the quality of administrative vaccination data in Uganda. Vaccine. 2020;38(5):1105–13.

Kintu JR. An evaluation of district health information system version 2.0 implementation process: evidence from south west Uganda: Uganda martyrs University. 2012.

Kiberu VM, Matovu JK, Makumbi F, Kyozira C, Mukooyo E, Wanyenze RK. Strengthening district-based health reporting through the district health management information software system: the Ugandan experience. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14(1):1–9.

Babirye JN, Rutebemberwa E, Kiguli J, Wamani H, Nuwaha F, Engebretsen I. More support for mothers: a qualitative study on factors affecting immunisation behaviour in Kampala. Uganda BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1–11.

Levin A, Kaddar M. Role of the private sector in the provision of immunization services in low-and middle-income countries. Health Polic Plan. 2011;26 (suppl_1):i4–12.

Kamya C, Namugaya F, Opio C, Katamba P, Carnahan E, Katahoire A, et al. Coverage and drivers to reaching the last child with vaccination in urban settings: a mixed-methods study in Kampala Uganda. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2022. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00663.

Mackintosh M, Channon A, Karan A, Selvaraj S, Cavagnero E, Zhao H. What is the private sector? understanding private provision in the health systems of low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2016;388(10044):596–605.

Kiiza D, Kisakye A, Chebrot I, Kwesiga B, Okello D, Kabwongera E, et al. The cost of routine immunization services in a poor urban setting in Kampala, Uganda: findings of a facility-based costing study. 2018.

Jitta DJ. Health delivery systems: Kampala City, Uganda. Building healthy cities. 2002.

Levin A, Munthali S, Vodungbo V, Rukhadze N, Maitra K, Ashagari T, et al. Scope and magnitude of private sector financing and provision of immunization in Benin. Malawi Ga Vaccin. 2019;37(27):3568–75.

Nyakaana J, Sengendo H, Lwasa S. Population, urban development and the environment in Uganda: the case of Kampala city and its environs. Faculty of Arts, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. 2007:1-24.

Tilahun B, Mekonnen Z, Sharkey A, Shahabuddin A, Feletto M, Zelalem M, et al. What we know and don’t know about the immunization program of Ethiopia: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–14.

Babirye JN, Engebretsen IM, Makumbi F, Fadnes LT, Wamani H, Tylleskar T, et al. Timeliness of childhood vaccinations in Kampala Uganda: a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4): e35432.

Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):1–12.

Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of health care interventions: a theoretical framework and proposed research agenda. Br J Health Psychol. 2018;23(3):519–31.

Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis J. Application of a theoretical framework to assess intervention acceptability: a semi-structured interview study. 2016.

West R, Michie S. A brief introduction to the COM-B Model of behaviour and the PRIME Theory of motivation [v1]. Qeios. 2020. https://doi.org/10.32388/WW04E6.2.

Willmott TJ, Pang B, Rundle-Thiele S. Capability, opportunity, and motivation: an across contexts empirical examination of the COM-B model. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–17.

Amico K, Wieland ML, Weis JA, Sullivan SM, Nigon JA, Sia IG. Capacity building through focus group training in community-based participatory research. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2011;24(3):638.

Tombor I, Michie S. Methods of health behavior change. Oxford research encyclopedias-psychology. Noida: Oxford University Press; 2017.

Jacobs JA, Duggan K, Erwin P, Smith C, Borawski E, Compton J, et al. Capacity building for evidence-based decision making in local health departments: scaling up an effective training approach. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):1–11.

Kasprowicz VO, Chopera D, Waddilove KD, Brockman MA, Gilmour J, Hunter E, et al. African-led health research and capacity building-is it working? BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Organization WH. Quality immunization services: a planning guide. 2022.

Shefer A, Santoli J, Wortley P, Evans V, Fasano N, Kohrt A, et al. Status of quality improvement activities to improve immunization practices and delivery: findings from the immunization quality improvement symposium, October 2003. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12(1):77–89.

Schwerdtle P, Morphet J, Hall H. A scoping review of mentorship of health personnel to improve the quality of health care in low and middle-income countries. Glob Health. 2017;13(1):1–8.

Etana B, Deressa W. Factors associated with complete immunization coverage in children aged 12–23 months in Ambo Woreda. Cent Ethiop BMC Publ Health. 2012;12(1):1–9.

Onyemelukwe C. Can legislation mandating vaccination solve the challenges of routine childhood immunisation in Nigeria? Oxf Univ Commonw Law J. 2016;16(1):100–24.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the contribution of the data collection team, the management of the participating private health facilities and the respondents who provided invaluable information in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (Alliance). The Alliance can conduct its work thanks to the commitment and support from a variety of funders. These include Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance contributing designated funding and support for this project, along with the Alliance's long-term core contributors from national governments and international institutions. For the full list of Alliance donors, please visit https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/partners/en/. Any opinion, conclusion or recommendation expressed in this material is that of the authors. The funder had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ES conceived the study; ES, SZK and ER designed the study protocol; ES and ER analysed the data and discussed the structure of the manuscript; ES wrote the first draft. SZK, PK, and YK provided a contextual interpretation of the results. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Therefore, the study received ethical approval from Makerere University School of Public Health Higher Degrees Research and Ethics Committee (HDREC) ref; HDREC 848 and was registered with the Ugandan National Council for Sciences and Technology (UNCST) under reference number: HS996ES. Further administrative clearance was obtained from the management of all participating health facilities and organisations where the study data collection was conducted. Individual informed consent was obtained from all prospective respondents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ssegujja, E., Kiggundu, P., Kayemba, Y. et al. Quality improvement interventions targeting immunization data from urban lower-level private-for-profit health service providers in Kampala Capital City: processes and implementation experiences. Discov Health Systems 3, 43 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00109-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00109-2