Abstract

The appropriateness and quality of prescribing in the elderly can be assessed through various methods and protocols. Each of them has certain advantages and disadvantages which should be taken into account when they are utilized in everyday practice and care for the geriatric population (people ≥ 65 years). The study aimed to perform a comprehensive literature review and comparison of the existing tools for the assessment of potentially inappropriate drug prescribing in the elderly. The literature search on explicit tools for potentially inappropriate prescribing drugs was performed through the PubMed databases for the period from 1991 until December 2022. The results are structurally presented with the year of publication of the criteria, organization of criteria, and their advantages and disadvantages. Twenty-five different explicit criteria were found in 92 published articles, based on different settings and written in different countries. Many protocols for the detection of potentially inappropriate drugs have been published in recent years, with overlaps between them and different implications for everyday practice. Further research is needed to determine the optimal characteristics of a tool for PIM detection and its role in the optimization of drug prescribing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In assessing the appropriateness of prescribing drugs to elderly people, various assessments of the procedure (content and quality) and/or the outcome of prescribing are used, which are divided into explicit (those based on certain standards) and implicit (those based on clinical assessment) criteria. Explicit criteria are usually formed according to literature systematic reviews and expert opinions based on the consensus technique. They are drug/drug–disease and may be administered with clinical judgment. As the complexity of pharmacotherapy and drug use is increasing, particularly among the elderly with multiple morbidities [1], drug risk management is becoming an increasingly important area of research. Some drugs are considered potentially inappropriate medication if their use carries a significant risk of side effects, especially if there is another equally effective or more effective drug for the treatment of the same condition or disease. These are drugs with an unfavorable benefit ratio and risk. PIM is associated with risks that outweigh the potential benefits, especially when effective therapeutic alternatives are available [2]. The use of PIM is an important public health challenge, with high prevalence rates, from 18 to > 40%, in different healthcare settings [3,4,5,6]. Providing safe drug therapy is considered one of the biggest challenges in geriatric health care and the prescription of PIM is widespread and associated with greater use of health care [7,8,9], an increased risk of adverse drug reactions such as falls, fractures, delirium [10], polypharmacy, morbidity, hospitalization [11,12,13], and mortality [14,15,16]. In recent years, many protocols and strategies have been developed to evaluate the quality of drug prescribing in the elderly. Developing such evidence-based protocols specifically for the elderly population is problematic, as older people are usually underrepresented or excluded from most efficacy and safety trials [17, 18].

2 Method

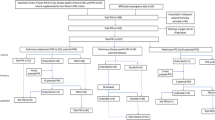

This review article is based on a literature search in the PubMed databases in the period from 1991 when the first explicit criteria were published, until December 2022 using the terms: ("Inappropriate Prescribing"[Mesh]) AND (explicit criteria). The search results are shown in (Fig. 1).

No limitations were posed on language. We excluded articles focusing on patients aged under 65 + years and out of our custom range. The results are structured according to the year of the publication of the criteria, organization of criteria, advantages and disadvantages of each criterion. Our objective was to describe and compare different explicit criteria, particularly in terms of covering three clinically important features, including therapeutic alternatives, drug–drug interactions, and drug–disease interactions. Additionally, to help the physicians with choosing a protocol in their practice, we looked for which criteria included all three essential items, which included at least one, and which included none. The findings were presented using descriptive statistics.

3 Results

Our search identified 129 articles, of which 25 included explicit criteria for detecting potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP). The characteristics of the explicit criteria are presented in Table 1.

Out of the 25 explicit criteria we assessed, only 11 criteria (44%) included a therapeutic alternative medication for individual PIM. Clinically important drug–drug interactions are included in 14 criteria (56%) and clinically important drug–disease interactions in 16 criteria (64%) (Table 2).

Among the 25 reviewed criteria, only 7 criteria (28%) had all three necessary items, 15 criteria (60%) had at least one of them, and 3 criteria (12%) did not include any of these items (Table 3).

From the List of explicit criteria STOPP/START criteria and FORTA criteria have been associated with positive patient-related outcomes when used as interventions in recent randomized controlled trials. STOPP/START criteria have been tested as an intervention in four RCTs. Gallagher and colleagues showed that, in older hospitalized patients, STOPP/START recommendations communicated to attending physicians at the time of hospital admission significantly improved medication appropriateness compared with usual pharmaceutical care. O’Connor and colleagues showed that this intervention significantly reduced nontrivial adverse drug reactions compared with usual pharmaceutical care (absolute risk reduction of 11.4%; number of patients needed to screen to prevent one ADR = 9). Frankenthal and colleagues showed that the application of STOPP/START recommendations significantly reduced polypharmacy, inappropriate medication use, incident falls, and the average monthly cost of medications in frail elderly nursing home residents. Dalleur and colleagues applied STOPP criteria to the prescriptions of hospitalized older patients in addition to a comprehensive geriatric assessment. They showed that from this intervention, the reduction in PIMs for the intervention group was double that for the control group at hospital discharge (39.7 and 19.3%, respectively; p = 0.013). FORTA list was evaluated in a randomized controlled trial involving 409 hospitalized patients in Germany. In the intervention group, the median number of medications did not change between hospital admission and discharge. In contrast, the median number of daily medications in the control group increased by one. The primary endpoint (i.e., FORTA score) was significantly reduced (i.e., improved) in the intervention group relative to the control group. Intervention patients also had significantly reduced incidence of ADRs with a number needed to screen of only five to prevent one clinically significant ADR. Furthermore, significant improvements in functional scores were noted in the intervention group relative to the control group [43].

4 Discussion

Although among the 25 criteria, most of the criteria (60%) included at least one of the three essential items (therapeutic alternatives, drug–drug interactions, and drug–disease interaction), only seven of them (28%) included all three items. Therapeutic alternatives, drug–drug interactions, and drug–disease interaction were considered in 44%, 56%, and 64% of the criteria, respectively. A significant number of publications on potentially inappropriate drug prescribing have shown increased interest in this topic in the last two decades and many attempts have been made to improve drug prescribing in the elderly. In a recent systematic review, it has been demonstrated that with the high prevalence of inappropriate drug prescribing, economic costs can be reduced with the optimization of prescribing inappropriate drugs. In this systematic review, estimates of PIM ranged between 21 and 79%, depending on the explicit criteria used for assessment and follow-up in heterogeneous healthcare settings [44]. Another 2021 systematic review" confirmed a pooled estimate PIM frequency of 46–56% in the hospital setting, depending on the tool used [45]. Research in different healthcare institutions showed PIM prevalence rates ranging from 8.6% in Germany to 81% in Australia [46]. The clinical and economic consequences of potentially inappropriate prescriptions (PIP) may be more devastating for older people living in regions and countries with fewer financial resources and poorer health status, contributing to deepening health inequalities globally. One such region is Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), where the proven prevalence of PIP in older people was 34.6%. Conducting an updated comprehensive systematic review across a range of settings can inform policymakers about the PIP problem in the CEE region and consequently reduce global health disparities and accelerate the development of drug safety measures in this region. Research findings suggest that PIP in older people is a highly prevalent problem, and their informal visual examination of heterogeneity showed that the prevalence of PIP was higher in long-term care and outpatient settings than in acute and community-based social care settings [47].

A limitation of the review is the possibility that we missed some explicit criteria because our search was limited to the PubMed database, and did not include a search of gray literature and other databases. The risk of publication bias may be considerable due to our decision to include only studies published as full-text articles in journals. We thought this would be the most reproducible and transparent approach due to a large volume of gray literature with unverified quality in this area and the absence of study registers and protocols. Despite this potential limitation, the strength of this review lies in it perhaps summarizing explicit criteria and their characteristics.

In sum, the key finding is that, the review showed an increasing trend of PIP over the years and that the higher prevalence of PIP over time may be due to the increased comprehensiveness of measurement protocols, which can identify more prescribing problems. We believe that clinically relevant, explicit recommendations delivered to the prescriber promptly, combined with emerging developments in pharmacogenomics, offers one way to stem the tide of inappropriate polypharmacy and associated adverse drug reactions and an adverse drug Events and to ensure optimal management of the rapidly growing global population of multimorbid older patients.

5 Conclusion

Ideal criteria for evaluating the quality of drug prescribing should include efficacy, safety, economic justification, patient preferences, and should be developed using evidence-based methods. None of the criteria described in this review covers all aspects of inappropriate drug prescribing. Many tools strongly emphasize the drug of choice to improve adherence to treatment guidelines. If the protocols are implemented in daily work, they warn healthcare professionals about inappropriate prescribing. Some protocols did not provide specific considerations for use and therapeutic alternatives to avoid potentially inappropriate treatment. Due to the complexity of the protocols, it is suggested that more than one protocol be used to adequately facilitate the evaluation process and improve the quality of care for the geriatric population. This article can serve as a summary to help researchers choose criteria, either for research purposes or for daily work to improve patient pharmacotherapy. Since each country has different prescribing habits, guidelines, market availability of drugs, and health systems, there is also a need to develop country-specific criteria and accurate assessments of inappropriate drug use, and this may explain the wide range of criteria published in recent decades. More research is needed to strengthen the existing evidence and increase the generalizability of the findings. Future lists of potentially inappropriate medications should include information on therapeutic alternatives, drug–drug interactions, drug–disease interactions, and special considerations for their use to assist healthcare professionals in prescribing medications to the geriatric population. Further research should determine the optimal characteristics of a tool for PIM detection and their role in the optimization of drug prescribing in the elderly. Future studies should be reported using appropriate guidelines.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Dimitrow MS, Airaksinen MS, Kivelä SL, et al. Comparison of prescribing criteria to evaluate the appropriateness of drug treatment in individuals aged 65 and older: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(8):1521–30.

Renom-Guiteras A, Meyer G, Thurmann PA. The EU(7)-PIM list: a list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people consented by experts from seven European countries. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(7):861–75.

Hedna K, Hakkarainen KM, Gyllensten H, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and adverse drug reactions in the elderly: a population-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(12):1525–33.

Morin L, Laroche ML, Texier G, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults living in nursing homes: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(9):862.e861 e862.e869.

Nyborg G, Straand J, Brekke M. Inappropriate prescribing for the elderly—a modern epidemic? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(7):1085–94.

Opondo D, Eslami S, Visscher S, et al. Inappropriateness of medication prescriptions to elderly patients in the primary care setting: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8): e43617.

Corsonello A, Pedone C, Incalzi RA. Age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes and related risk of adverse drug reactions. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(6):571–84.

Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57(1):6–14.

Hanlon JT, Shimp LA, Semla TP. Recent advances in geriatrics: drug-related problems in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(3):360–5.

Lund BC, Carnahan RM, Egge JA, et al. Inappropriate prescribing predicts adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(6):957–63.

Cabré M, Elias L, Garcia M, et al. Avoidable hospitalizations due to adverse drug reactions in an acute geriatric unit. Analysis of 3,292 patients. Med Clin. 2018;150(6):209–14.

Price SD, Holman CD, Sanfilippo FM, et al. Association between potentially inappropriate medications from the Beers criteria and the risk of unplanned hospitalization in elderly patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(1):6–16.

Reich O, Rosemann T, Rapold R, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in older patients in Swiss managed care plans: prevalence, determinants and association with hospitalization. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8): e105425.

Klarin I, Wimo A, Fastbom J. The association of inappropriate drug use with hospitalisation and mortality: a population-based study of the very old. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(1):69–82.

Lau DT, Kasper JD, Potter DE, et al. Hospitalization and death associated with potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions among elderly nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(1):68–74.

Muhlack DC, Hoppe LK, Weberpals J, et al. The association of potentially inappropriate medication at older age with cardiovascular events and overall mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(3):211–20.

Cherubini A, Oristrell J, Pla X, et al. The persistent exclusion of older patients from ongoing clinical trials regarding heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(6):550–6.

Crome P, Lally F, Cherubini A, et al. Exclusion of older people from clinical trials: professional views from nine European countries participating in the PREDICT study. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(8):667–77.

McLeod PJ, Huang AR, Tamblyn RM, et al. Defining inappropriate practices in prescribing for elderly people: a national consensus panel. CMAJ. 1997;156(3):385–91.

Malone DC, Abarca J, Hansten PD, et al. Identification of serious drug–drug interactions: results of the partnership to prevent drug–drug interactions. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44(2):142–51.

Lindblad CI, Hanlon JT, Gross CR, et al. Clinically important drug–disease interactions and their prevalence in older adults. Clin Ther. 2006;28(8):1133–43.

Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Merle L. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: a French consensus panel list. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(8):725–31.

Raebel MA, Charles J, Dugan J, et al. Randomized trial to improve prescribing safety in ambulatory elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):977–85.

Basger BJ, Chen TF, Moles RJ. Validation of prescribing appropriateness criteria for older Australians using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. BMJ Open. 2012;2: e001431.

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) (2008) HEDIS—high risk medications (DAE-A) and potentially harmful Drug Disease Interactions (DDE) in the Elderly: www.ncqa.org/tabid/598/. Accessed 10 Dec 2022.

Matsumura Y, Yamaguchi T, Hasegawa H, et al. Alert system for inappropriate prescriptions relating to patients’ clinical condition. Methods Inf Med. 2009;48(6):566–73.

Terrell KM, Perkins AJ, Dexter PR, et al. Computerized decision support to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing to older emergency department patients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1388–94.

Maio V, Del Canale S, Abouzaid S, et al. Using explicit criteria to evaluate the quality of prescribing in elderly Italian outpatients: a cohort study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2010;35(2):219–29.

Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thurmann PA. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(31–32):543–51.

Kölzsch M, Bolbrinker J, Huber M, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication for the elderly: adaptation and evaluation of a French consensus list. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2010;33(8):295–302.

Mann E, Böhmdorfer B, Frühwald T, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication in geriatric patients: the Austrian Consensus Panel List. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124(5–6):160–9.

Mimica Matanović S, Vlahović-Palčevski V. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: a comprehensive protocol. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(8):1123–38.

Castillo-Páramo A, Pardo-Lopo R, Gómez-Serranillos IR, et al. Assessment of the appropriate ness of STOPP/START criteria in primary health care in Spain by the RAND method. SEMERGEN. 2013;39(8):413–20.

Clyne B, Bradley MC, Hughes CM, et al. Addressing potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients: development and pilot study of an intervention in primary care (the OPTI-SCRIPT study). BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:307.

Van der Linden L, Decoutere L, Walgraeve K, et al. Development and validation of the RASP list (Rationalization of Home Medication by an Adjusted STOPP list in Older Patients): a novel tool in the management of geriatric polypharmacy. Eur Geriatr Med. 2014;5(3):175–80.

Kuhn-Thiel AM, Weiss C, Wehling M. Consensus validation of the FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) list: a clinical tool for increasing the appropriateness of pharmacotherapy in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(2):131–40.

Galán Retamal C, Garrido Fernandez R, Fernandez Espinola S, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication in hospitalized elderly patients by using explicit criteria. Farm Hosp. 2014;38(4):305–16.

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213–8.

Nyborg G, Straand J, Klovning A, et al. The Norwegian general practice-nursing home criteria (NORGEP-NH) for potentially inappropriate medication use: a web-based Delphi study. Scand J Primary Health Care. 2015;33(2):134–41.

Tommelein E, Petrovic M, Somers A, et al. Older patients’ prescriptions screening in the community pharmacy: development of the Ghent Older People’s Prescriptions community Pharmacy Screening tool (GheOP3S). J Public Health (Oxf). 2016;38(2):e158–70.

Pazan F, Weiss C, Wehling M, et al. The EURO-FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) list: international consensus validation of a clinical tool for improved drug treatment in older people. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(1):61–71.

Chahine B. Potentially inappropriate medications prescribing to elderly patients with advanced chronic kidney by using 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria. Health Sci Rep. 2020;3(4): e214.

Curtin D, Gallagher PF, O’Mahony D. Explicit criteria as clinical tools to minimize inappropriate medication use and its consequences. Therapeut Adv Drug Saf. 2019;10:204209861982943.

Mucherino S, Casula M, Galimberti F, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to evaluate and reduce healthcare costs of potentially inappropriate prescriptions among the older adults: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(11):6724.

Mekonnen AB, Redley B, de Courten B, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and its associations with health-related and system-related outcomes in hospitalised older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87:4150–72.

Malakouti SK, Javan-Noughabi J, Yousefzadeh N, et al. A systematic review of potentially inappropriate medications use and related costs among the elderly. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021;25:172–9.

Brkic J, Fialova D, Okuyan B, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults in Central and Eastern Europe: a systematic review and synthesis without meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):16774.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MV was involved in the conception and design of the study, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. SM was involved in the conception and design of the study, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. This manuscript has not been submitted elsewhere for consideration of publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential competing interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Non-financial interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vukoja, M., Mimica, S. Comparison of explicit criteria for potentially inappropriate drug prescribing among the elderly: a narrative review. Discov Health Systems 3, 62 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00102-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00102-9