Abstract

Situation awareness is knowing what is going on in the situation. Clinicians working in the emergency medical services (EMS) encounter numerous situations in various conditions, and to be able to provide efficient and patient safe care they need to understand what is going on and possible projections of the current situation. The design of this study encompassed a Goal-Directed Task analysis where situation awareness information requirements were mapped in relation to goals related to various aspects of the EMS mission. A group of 30 EMS subject matter experts were recruited and answered a web-based survey in three rounds related to what they though themselves or a colleague might need to achieve situation awareness related to the specific goals of various situations. The answers were analysed using content analysis and descriptive statistics. Answers reached consensus at a predetermined level of 75%. Those who reached consensus were entered into the final goal-directed task analysis protocol. The findings presented that EMS clinicians must rely on their own, or their colleagues prior experience or knowledge to achieve situation awareness. This suggests that individual expertise plays a crucial role in developing situation awareness. There also seems to be limited support for situation awareness from organizational guidelines. Furthermore, achieving situation awareness also involves collaborative efforts from the individuals involved in the situation. These findings could add to the foundation for further investigation in this area which could contribute to the development of strategies and tools to enhance situation awareness among EMS clinicians, ultimately improving patient care and safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

1.1 Situation awareness

Most of the various definitions and models of situation awareness (SA) refer in some way to ‘knowing what is going on in a specific situation’. SA is considered a crucial construct in the context of individual or team decision making within a system involving physical or perceptual tasks that depend on human performance [1, 2]. To that extent, any discussion of SA must also take account of human behaviour. According to Mica Endsley, there are three distinct levels of SA: (1) perception of elements in the current situation; (2) comprehension of the current situation; and (3) projection of future status [2]. All three levels contribute to the individual’s or group’s understanding of the situation and inform their decisions and actions. Inaccurate or ill-informed SA is likely to result in a wrong decision. Equally, SA alone may not suffice to prevent faulty decision-making or poor performance if the individual or group lacks the necessary training to execute the relevant procedures, tactics, or actions [1, 2].

Individual attention and working memory are among the issues that may influence SA, along with workload and stress. Acquiring and maintaining SA becomes more difficult as situations become more complex and dynamic. In dynamic situations, for example, multiple decisions may have to be made in a relatively short time while processing and analysing constant updates. While the present study addresses SA in the context of human performance in complex systems, SA also plays a significant role in everyday activities in which effective functioning depends on dynamic updates (e.g. walking or driving in a busy environment) [1].

Level 1 of SA relates to the status, attributes, and dynamics of salient elements of the situation, otherwise known as informational cues. For example, a car driver needs to be aware of the location, behaviour and movement of other vehicles, people, and obstacles. Level 2 involves comprehension of the situation based on an analysis of the informational cues from Level 1. As well as grasping how these cues relate to each other, Level 2 assesses their meaning in relation to the individual’s or system’s goals (e.g. avoiding other vehicles). In this regard, an experienced individual may have an advantage in terms of their ability to perceive and combine the various informational cues from Level 1 and how they relate to the relevant goals. Finally, Level 3 involves the projection or anticipation of how given elements of the situation will change in the near future (e.g. predicting the future position of an oncoming vehicle). This highest level of SA incorporates information from Levels 1 and 2. Both Level 2 and Level 3 awareness inform the individual’s active search for informational cues in Level 1. Research on SA have been conducted for the last three decades, and various ways of testing or investigating SA have been developed [3]. One of the commonly used means for measuring is the Situation Awareness Global Assessment Technique (SAGAT), its commonly used in simulated scenarios which includes representative tasks.

Previous research on SA has typically focused on high-risk contexts such as aviation, large-system operations in production industries or tactical and strategic systems [1]. The present study contributes to the literature by exploring another high-stakes context: emergency medical services (EMS), focusing in particular on ambulance care.

1.2 SA in EMS settings

Ambulance care and the associated clinicians are an important component of the EMS system [4,5,6]. EMS clinicians encounter and care for patients of every age, gender, socioeconomic status and religious background and must deal with every kind of actual or perceived threat to their health and well-being by providing 24/7 care under widely varying conditions. The EMS context consists of various tasks that need to be conducted in a dynamic environment. These tasks are primarily physical or perceptual and might need to be managed with some haste due to potential emergencies within the situation, which can be related to the patient’s condition or environmental factors. To take appropriate action, clinicians must be able to rapidly develop an understanding of these dynamic and unpredictable situations [7,8,9], and SA is a crucial element of that understanding. Previous research suggests that EMS clinicians begin to develop a mental projection of the patient and their situation as soon as they receive the dispatch information. This projection is then revised in light of what they encounter at the scene as they begin to interpret a range of informational cues. Decisions are made on the basis of what seems appropriate in the immediate circumstances and what seems likely to benefit the patient in the long run [9, 10]. An EMS mission can be viewed as a series of more or less well-defined tasks; to support clinicians in this process, it is crucial to understand the endpoints of these tasks and what it takes to complete them. Research suggests that EMS work is protocol driven [11], but also that EMS clinicians describes a lack of support from their guidelines as these are not contextually appropriate [10]. This conflict creates a need for creativity to solve the situation, a creativity which is based on the EMS clinicians understanding of the situation. Furthermore, there seemingly are a lack of descriptive studies regarding SA in the EMS context [12]. As SA is directly linked to decision making it is highly influential for not only patient outcome but also the safety of clinicians and others involved at the scene [1]. Based on previous patient safety studies healthcare organisations struggles with minimizing the impact of faulty decision making related to medical errors, decisions which in most likely are informed by SA [13]. These problem are most likely also found in the EMS.

1.3 Goal-directed task analysis

EMS care provision involves significant cognitive work under dynamic and varied conditions. To meet that challenge, clinicians must develop and maintain adequate SA, as this forms the basis for decision-making. Goal-directed task analysis (GDTA) seeks to clarify the goals of a specific task, the decisions that must be made to achieve these goals and the associated information processing requirements. GDTA is likely to be of assistance when developing new systems to support decision-makers or evaluating existing systems [14].

The only previous GDTA performed in an EMS setting focused on the role of advanced paramedics as emergency care practitioners [15, 16]. In that study, Hamid described SA requirements and limitations in the context of paramedics’ cognitive work [16]. While any direct international comparison is difficult because standards of education and care provision differ [4, 5, 17], it seems important to develop an understanding of EMS clinicians’ SA during ambulance missions and patient encounters in order to identify support needs and so enhance the accuracy of SA as a basis for appropriate and safe decision-making. To that end, the present study employed GDTA to map SA Levels 2 and 3 in the context of EMS ambulance missions. The aim being to build an understanding of what an EMS clinician needs to form SA during a general ambulance mission.

2 Methods

Employing an inductive mixed-methods approach, the present GDTA [14] was informed by a critical realist ontology [18]. The process was modified to minimise any disruption of subject matter expert (SME) activities and to fit an agreed timeframe.

2.1 Design

The authors drew on published research findings [9, 10, 15, 16] to ground the study protocol and to define task goals, subgoals and decision points. In the first phase of the study (January to March 2022), goals were specified chronologically in terms of the generic timeline of an ambulance mission [19]. In the second phase (February, 2022), a panel of SMEs was recruited to inform and validate the subgoal/decision requirements for SA Levels 2 and 3. To that end, the participating SMEs completed three rounds of a web-based survey (SurveyMonkey) between April and June 2022. In the third and final phase (September to October 2022), the SA requirements identified and agreed by the SMEs were incorporated into the GDTA-protocol [14].

2.2 Participants

Purposive sampling was used to recruit the SMEs; they included registered nurses with a specialist education in ambulance care and at least 5-years’ clinical experience and EMS teachers or researchers from across Sweden. In total, 47 invitations to participate were sent via email, accompanied by an information letter. Thirty of the targeted candidates responded positively; five declined, and twelve did not respond to the invitation. Table 1 summarises the key demographic details of the participating SMEs.

2.3 Survey procedures

In all three rounds, the first page of the survey described SA and its three levels, along with two examples. SMEs were invited to reach out if they had any questions about the survey’s content and purpose. After receiving each round of the survey by email through the online system, participants were allowed 14 days to respond; two reminders were sent (after five and ten days) to any participant who failed to respond or to fully complete the survey.

In the first round of the survey, the participating SMEs were asked to describe in their own words anything that might help them to understand (Level 2) or anticipate (Level 3) specific ambulance mission situations related to the specified goals and decisions (Supplementary files 1 and 2—Initial GDTA phase 1–6 and Table of statements). The survey questions included What do you need in order to understand the potential risks at the patient’s location? and What do you need in order to anticipate possible options for treating the patient’s condition? The open-ended answers were analysed inductively, using content analysis [20] to cluster similar content-related items. These clusters were reviewed and restated as SA Level 2 and 3 activities. These statements formed the basis for the second round of the survey.

In the second round, SMEs were asked to rate the level of importance of each statement on a four-point scale (1: not at all true; 2: rarely true; 3: more or less true; 4: absolutely true). Respondents were also free to suggest additional SA requirements. A statement was deemed to achieve consensus if 75% of respondents scored it 1 or 2 (not true) or 3 or 4 (true). Statements could receive either a positive (Y +) or negative (Y −) consensus based on the SME rating. Statements that achieved consensus were removed from the survey and the positive (+) ones were incorporated in the final protocol; those that did not achieve consensus remained in the survey, and any new suggestions were added in the next round. The third round followed the same procedure. (All statements and associated consensus data are listed in the Table of statements in Supplementary file 2).

2.4 Ethical considerations

Based on Swedish law [21] and the provisions of the Research Ethics Approval Committee (Reference Number 2022-00176-01), the study did not require ethical approval. The study prioritised participant integrity, confidentiality, and informed consent in line with the Declaration of Helsinki [22] and the Swedish Data Protection Act [23]. The survey information specified that participation in the study was voluntary, and that survey completion would be regarded as consent.

3 Results

The results as presented here correspond to and describe the phases of the GDTA-process. At this point, it is important to note that consensus regarding a given statement does not necessarily mean it is true (or false) but simply reflects the respondents’ opinions. In interpreting the results, one must therefore consider whether that opinion applies in every situation or to all EMS clinicians. In addition, other confounding factors may influence the views of present and future respondents.

3.1 Phase 1: Formulation of goals, subgoals and decision points

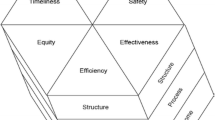

Based on the existing literature, the authors reasoned that the main goal of an ambulance mission is to provide safe, timely and adequate patient care. On that basis, an ambulance mission can be divided into six generic phases: receiving the mission and driving to the patient; arrival at the scene; assessment and treatment at the scene; departure from the scene; transportation; and handover and reporting. For each of these phases, subgoals were identified that align with decisions that must be taken to achieve the desired goal. Figure 1 shows the initial steps of the task analysis; the complete mission is detailed in Supplementary file 1 (Initial GDTA phase 1–6).

3.2 Phase 2: SME survey

The first-round survey included 64 items; of these, 4 sought information about the participant’s background, and 60 related to specific subgoals. In total, 23 participants completed the full survey, and 7 responded only in part (Table 2). The analysis of free-text responses to the 60 items generated 364 statements (min = 3, max = 9, mean = 6.3), and these informed the second survey round.

For the second round of surveys, some statements were assigned to clusters that included ‘having specific knowledge’ and ‘being able to…’. The former refers to theoretical and practical knowledge of something—for example, geographical knowledge of the EMS catchment area would include an awareness of specific local conditions such as rush-hour traffic, making a longer or slower alternative route more suitable. Similarly, knowing which neighbourhoods are more challenging serves to heighten risk awareness. ‘Being able to…’ refers to a clinician’s ability and willingness to share or listen to the information provided (which is, of course, a two-way transaction).

In the second round, 21 SMEs completed the survey in full; 3 respondents provided partial answers, and 6 dropped out (see Table 2). Statements that reached the 75% consensus level (n = 309) were removed from the survey and saved. Suggestions regarding additional statements (n = 11) were included in the next round, along with statements that failed to gain consensus (n = 55).

In the third and final round, 24 SMEs completed the full survey, and 19 statements achieved consensus while 47 did not. There were three new suggestions; the authors discussed whether these warranted an additional round but concluded that data collection should end, as the suggestions related to statements that had already achieved consensus. In all, 328 statements achieved consensus while 47 did not. Full details of all statements and percentages can be found in Supplementary file 2 (Table of statements). Any statements deemed essential for SA Level 2 or 3 were included in the GDTA protocol for the third phase.

3.3 Phase 3: Combining the initial GDTA and survey results

Based on the survey results, the GDTA protocol was further developed to incorporate the requirements for SA Levels 2 and 3 (Fig. 2). The protocols for all mission phases can be found in Supplementary file 3 (Final GDTA phase 1–6).

To meet the first goal (finding the most suitable route to the patient), EMS clinicians must understand the limitations of GPS route recommendations. Specifically, GPS often identifies only the shortest or quickest route based on distance or speed limits. However, clinicians with adequate map-reading skills can identify alternative routes and where these intersect. Geographical knowledge of the catchment area enables clinicians to understand and anticipate the most suitable route according to the prevailing weather conditions or the time of day (e.g. rush hour). Geographical knowledge may also include awareness of poor road conditions on specific routes that might prolong journey times or increase the risk of vehicle damage. To some extent, this also involves knowledge of a specific vehicle’s behaviour and handling, which contributes to safe driving.

The ability to make full and appropriate use of dispatch information is likely to depend in part on the quality of information from the caller regarding useful landmarks. Dispatch information may also alert clinicians to potential obstacles or risks along certain routes, which can help in understanding and anticipating situations that may arise during the outward journey. Based on previous experience, colleagues may also be able to provide information or instructions that can help to identify a suitable route to the patient’s location. However, this can only contribute to situational awareness if both clinicians are willing to share and incorporate the relevant information.

In the first phase of the ambulance mission, the third goal is to understand and anticipate what preparations are needed and what the clinicians are about to encounter. Based primarily on inputs from the dispatch centre, clinicians must apply medical, caring, and ethical principles and knowledge when interpreting this information. Again, colleagues and people already at the scene may be able to assist clinicians’ preparations by appraising them of additional situational factors.

4 Discussion

Overall, these findings confirm that EMS clinicians must rely on their own or their colleagues’ knowledge and prior experience of similar situations to reach SA Levels 2 and 3. Organisational guidelines may only provide the support required to understand or anticipate what might happen related to assessing treatment options and care pathways. While the present study employed GDTA to identify generic goals and decisions, a deeper understanding of SA requirements during EMS mission phases can only be gained by investigating specific events. This approach has proved successful in other domains such as maritime navigation, where GDTA has been used to study specific manoeuvres [24]. GDTA can also be used to explore different scenarios or to show that different goals may depend on the same information [25]. However, while focusing on a specific event may provide deeper insights, that approach may fail to comprehend the complexity of a situation that involves multiple decisions or goals. This is true in the case of EMS missions, which vary widely in terms of the number of patients, their condition and environmental factors such as safety and logistics [10]. The present findings represent a first step towards mapping and understanding SA information requirements during EMS missions, but further research is needed, focusing perhaps on specific mission events that demand greater Level 1 SA.

The present findings regarding prior individual or team experience and knowledge align with the work of Hamid [15] and Dishman et al. [26]. The latter studied SA among anaesthesia nursing students and, as here, found that Level-2 SA requires clinicians to draw on their education, training and past experiences to understand a given situation or event. The present findings also confirm the importance of team SA, and Hamid [16] reported that the patient and their loved ones play a significant role in team SA performance by facilitating clinicians’ understanding and anticipation of specific situations. In contrast, poor communication hinders SA.

While Hamid’s [16] research focused on the physical encounter with the patient as the source of the most valuable information, EMS missions also involve mental preparation en route to the patient and preparation for handover to the receiving care unit [9, 10]. Nevertheless, Hamid’s results strengthen the present finding that accurate assessment of individual and team capabilities is a crucial element of SA, as is the ability to keep an open mind and to recognise the limitations of the available guidelines [16]. Knowledge of the healthcare system and what is possible also contributes to SA—for example, knowing where and when suitable care can be accessed. Hamid [16] referred to the clinician’s ability to suggest appropriate options based on their awareness of the available resources. Hamid [16] also noted the importance of patient records for SA and for choosing appropriate care. In the present case, the role of patient records did not achieve consensus, perhaps because many of Sweden’s EMS organisations do not offer clinicians access to patient records for use in the field. Access to patient records seems likely to provide a more solid foundation for SA and related decision making, and international work on this issue is ongoing [27].

The team contribution to SA cannot be overstated, and sharing the same mental model when processing the available information about a given situation is crucial for team SA [28]. In EMS settings, the team extends beyond clinicians to the patient and their loved ones and to other actors at the scene. Information from all of these sources can help to enhance SA and facilitate understanding of the available options for action. As previous studies have noted, actively involving the patient and other relevant actors in the situation can promote a sense of security and trust [29, 30].

In the present case, the authors pondered why some statements failed to achieve consensus. One possible explanation is that some informal work practices may not be willingly reported in a research setting; for example, ‘flagging of potentially risky patients or addresses’, which is often based on the experiences of others, is a matter of ongoing debate among Swedish emergency workers (ambulance, fire and police) in light of certain problematic aspects of this issue. In the absence of formal guidelines, EMS clinicians who enter these addresses or encounter these patients must depend on personal or shared experiences and recollections.

In combination with Hamid [16], the present findings provide the basis for a SAGAT protocol that could be used to evaluate SA during simulated patient encounters [3, 31]. Such a protocol would facilitate the testing of new support systems for EMS clinicians prior to clinical deployment.

4.1 Reflections on method

The original description of GDTA recommends that SME should be interviewed to gain an initial understanding of relevant goals and informational cues [14]. The current study drew instead on the existing literature to specify the goals, subgoals and decision points of an EMS mission while the participating SMEs were asked to identify the requirements for SA Levels 2 and 3. This approach was largely determined by time constraints and ensured that the respondents were not unduly disrupted or overwhelmed.

The chosen approach may have influenced the study findings in a number of ways. First, a face-to-face meeting and interview might have enabled a fuller introduction to the concept of SA and its various levels. Asking the SMEs about SA Level 1 may have provided more detailed descriptions, but this would also have added to the time and effort needed to complete the survey. Time was a central concern, as the authors hoped the SMEs would complete all three rounds of the survey in full despite their busy schedules. The online form was therefore a reasonable choice, as it allowed participants to access and complete the survey at their own pace and convenience. This may account for the relatively high participation rate and the low rate of dropout; it may also indicate that the respondents were interested in the research topic [32].

One possible limitation of the study relates to the survey design. For example, in the first round, two respondents completed only the demographics section. As participants had the right to withdraw without explanation, it was difficult to evaluate the precise reasons for this. Clearly, completing the survey was time-consuming, and lower individual levels of commitment may have contributed to dropout. However, the survey would have been more time-consuming if respondents were asked about SA Level 1 or interviewed face-to-face. While face-to-face interviews would undoubtedly have provided additional detail and opportunities for follow-up questions and clarifications, the authors felt that the existing literature provided sufficient information in some respects.

The respondents’ experience in EMS clinical work, research and education might be considered a strength or a limitation. For example, while less experienced participants may have offered different responses, those with longer and more varied experience could reflect on a wide range of patient encounters and fluctuating environmental and organisational conditions. Overall, as levels of consensus were relatively high, one can reasonably assume that these statements are valid across most Swedish EMS organisations.

The authors’ prior research and clinical experiences in this domain may have influenced their interpretation of the first-round survey responses and overall. To address this concern, the authors discussed their interpretations to check for any possible preconceptions. All findings were discussed until consensus was reached. As the study was conducted from a Swedish EMS perspective, the findings may not be generalisable to EMS or healthcare organisations in other countries, and the reader should reflect on this issue in their own context. In general, it seems that the findings are echoed to some extent in the United Kingdom EMS [15, 16].

There were issues related to the transferring of statements between the survey rounds. Two received a consensus in Round 2 but were transferred and questioned again in Round 3, the authors choose to present the results from both Rounds. Also, eight statements did not receive consensus in Round 2 and were not transferred to Round 3 even if they should have been. This is considered a limitation.

4.2 Implications and future research

The present results offer a basis for the development of a SAGAT-protocol [3, 31] and for assessing whether SA requirements vary according to the prevailing conditions. In any event, the findings have a number of interesting implications.

-

EMS clinicians’ SA is heavily dependent on team knowledge and experience. Future research should investigate the development of support tools to enhance SA.

-

Beyond the clinicians, other actors such as the patient, their loved ones and persons at the scene are potential contributors to SA, and all available sources of information should be fully exploited.

5 Conclusion

Among EMS clinicians, SA relies on the salient prior experiences and knowledge of individual clinicians and their colleagues. In short, the team plays a key role by contributing to a shared mental model that suggests what actions might be appropriate in the prevailing circumstances. In an EMS mission the team may consist of tighter and looser couplings with various actors that come and go during the mission, but they all have the possibility to contribute to the development of SA. This team effort is especially important when organisational guidelines offer only limited advice about treatment options or care pathways. Because SA is a difficult concept to grasp, EMS organisations find it difficult to support. Nevertheless, it seems important to engage in further research to support the development of SA among EMS clinicians, as this is clearly a key factor in patient safety. Future research should be aimed at specific aspects of the EMS mission, or possible directed towards a specific condition to better understand the forming of SA in relation to these.

Data availability

Data on which the result is founded on is presented in the supplementary files of this article.

Abbreviations

- EMS:

-

Emergency medical services

- GDTA:

-

Goal-directed task analysis

- SA:

-

Situation awareness

- SAGAT:

-

Situation awareness global assessment technique

- SME:

-

Subject matter experts

References

Endsley MR. Situation awareness misconceptions and misunderstandings. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak. 2015;9(1):4–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555343415572631.

Endsley MR. Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Hum Fact. 1995;37(1):32–64. https://doi.org/10.1518/001872095779049543.

Endsley M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of direct objective measures of situation awareness: a comparison of SAGAT and SPAM. Hum Fact. 2021;63(1):124–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720819875376.

Al-Shaqsi S. Models of international emergency medical services (EMS) systems. Oman Med J. 2010;25(4):320–3. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2010.92.

Bos N, Krol M, Veenliet C, Plass AM. Ambulance care in Europé—organization and practices of ambulance services in 14 European countries. Nivel: The Netherlands; 2015. Available at: https://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Rapport_ambulance_care_europe.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2022.

World Health Organization Europe: Emergency Medical Services Systems in EU: Report of an Assessment Project Coordinated by the WHO; 2008. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/114406/E92038.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2022.

Reay G, Rankin JA, Smith-MacDonald L, Lazarenko GC. Creative adapting in a fluid environment: an explanatory model of paramedic decision making in the pre-hospital setting. BMC Emerg Med. 2018;2018(18):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-018-0194-1.

Lindström V, Bohm K, Kurland L. Notfall + rettungsmedizin; 2015; 18:107–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10049-015-1989-1.

Andersson U, Andersson Hagiwara M, Wireklint Sundström B, Andersson H, Maurin Söderholm H. Clinical reasoning among registered nurse in emergency medical services: a case study. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak. 2022;16(3):123–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/15553434221097788.

Andersson U, Maurin Söderholm H, Wireklint Sundström B, Andersson Hagiwara M, Andersson H. Clinical reasoning in the emergency medical services: an integrative review. Scand J Trauma Resuscit Emerg Med. 2019;27:76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-019-0646-y.

Jensen JL. Paramedic clinical decision-making: result of two Canadian studies. J Paramed Pract. 2011;1(2):63–71. https://doi.org/10.12968/ippr.2011.1.2.63.

Hunter J, Porter M, Williams B. What is known about situational awareness in paramedicine? A scoping review. J Allied Health. 2019;48(1):e27–34.

Sitterding MC, Broome ME, Everett LQ, Ebright P. Understanding situation awareness in nursing work: a hybrid concept analysis. Adv Nurs Sci. 2012;35(1):77–92.

Hoffman RR, Crandall B, Klein G. Protocols for cognitive task analysis. Report, Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition. Pensacola, FL; 2005. Available at: https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a475456.pdf. 2023-03-07.

Hamid HA, Waterson P. Chapter 74—Using goal directed task analysis to identify situation awareness requirements of advanced paramedics. In: Vincent GD, editors, Advances in human factors and ergonomics in healthcare. Department of Ergonomics (Human Sciences) Loughborough University, England. CRC Press; 2010.

Hamid HSA. Situation awareness amongst emergency care practitioners. Loughborough University. Thesis; 2011. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/9114.

Rief M, Auinger D, Eichinger M, Honnef G, Schittek GA, et al. Physician utilization in prehospital emergency medical services in Europe: an overview and comparison [English, Spanish]. Emergencias. 2023;35(2):125–35.

Schiller CJ. Critical realism in nursing: an emerging approach. Nurs Philos. 2016;17:88–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/nup.12107.

Andersson Hagiwara M, Lundberg L, Sjöqvist BA, Maurin Söderholm H. The effects of integrated IT support on the prehospital stroke process: results from a realistic experiment. J Healthc Inform Res. 2019;2019(3):300–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41666-019-00053-4.

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

Swedish Government, SFS 2003:615: Förordning om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor [Swedish] [Regulation of ethical approval for research involving humans]. Available at: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/forordning-2003615-om-etikprovning-av_sfs-2003-615. Accessed, March 20, 2023.

World Medical Association: Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, 2013. Available at: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/. Accessed September 20, 2022.

Swedish Government, SFS 2018:218: Lag med kompletterande bestämmelser till EU: s dataskyddsförordning [Swedish] [Law with supplementary regulations to the European Union data protection act]. Available at: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2018218-med-kompletterande-bestammelser_sfs-2018-218. Accessed September 20, 2022.

Haffaci K, Massicotte M-C, Doyon-Poulin P. Goal-directed task analysis for situation awareness requirements during ship docking in compulsory pilot area. In: Black NL, Neumann WP, Noy I, editors, Proceedings of the 21st congress of the international ergonomics association (IEA 2021). IEA 2021. Lecture notes in networks and systems, vol. 221. Cham: Springer; 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74608-7_79.

Rezaeifam S, Ergen E, Günadydin HM. Fire emergency response systems information requirements’ data model for situational awareness of responders: a goal directed task analysis. J Build Eng. 2023;63(A):10531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105531.

Dishman D, Fallacaro MD, Damico N, Wright MC. Adaptation and validation of the situation awareness global assessment technique for nurse anesthesia graduate students. Clin Simul Nurs. 2020;43:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2020.02.003.

Porter A, Badshah A, Black S, Fitzpatrick D, Harris-Mayes R, et al. Electronic health records in ambulances: the ERA multiple-methods study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals library; 2020 Feb. PMID: 32119231. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr08100.

Al-Moteri M. Mental model for information processing and decision-making in emergency care. PLoS ONE. 2023;17(6):0269624. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269624.

Kauppi W, Axelsson C, Herlitz J, Jiménez-Herrera M, Palmér L. Lived experiences of being cared for by ambulance clinicians when experiencing breathlessness—a phenomenological study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2023;37(1):207–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.13108.

Venesoja A, Castrén M, Tella S, Lindström V. Patients’ perceptions of safety in emergency medical services: an interview study. BMJ Open. 2020;2020(10):e037488. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037488.

Jones DG, Kaber DB. Situation awareness measurement and the situation awareness global assessment technique. In: Stanton NA, Hedge A, Brookhuis K, Salas E, Hendrick HW, editors. Handbook of human factors and ergonomics methods. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2004. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203489925.

Holtom B, Baruch Y, Aguinis H, Ballinger GA. Survey response rates: trends and a validity assessment framework. Hum Relat. 2022;75(8):1560–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211070769.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants for their valuable time spent answering the various survey rounds.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

UA and MAH created the initial GDTA. UA and HA created the web-based survey and the consecutive analysis of each round. UA produced the initial manuscript, figures, and tables. All authors participated and contributed to the overall study design, analysis and presentation of findings, and the recruiting of participants. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Based on Swedish law [20] and the provisions of the Research Ethics Approval Committee (Reference No. 2022-00176-01), the study did not require ethical approval. Participants were informed of the study and that answering the web-survey were to be considered an informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andersson, U., Maurin Söderholm, H., Andersson Hagiwara, M. et al. Situation awareness in Sweden’s emergency medical services: a goal-directed task analysis. Discov Health Systems 2, 44 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-023-00061-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-023-00061-7