Abstract

Introduction

Health professional regulators have a mandate to ensure ongoing competence of their regulated members (registrants). Programs for monitoring and assessing continuing competence are one means of assuring the public of the quality of professional services. More regulators are adopting programs for continuing competence that require registrants to demonstrate reflective practice and practice improvement. More research on the effectiveness of reflection-based programs for continuing competence is needed. This study describes the evaluation of a reflection-based continuing competence program used by a regulator in Alberta, Canada.

Methods

Submission of a Continuing Competence Learning Plan (CCLP) is a requirement for practice permit renewal each year. CCLP submissions were randomly selected over a two-year period and rated according to a rubric. CCLP submission ratings and quality and quantity of content were compared. CCLP submission ratings were also compared to demographic and practice profile variables to identify significant relationships that could be used for risk-based selection of CCLP submissions in the future.

Results

Most registrants selected for review completed acceptable CCLP submissions that included reflective content. There was a relationship between CCLP submission rating and the gender identity of participants. There was no relationship between CCLP submission rating and participants' age, years since graduation, practice area, role or setting, client age range, or geographic location of primary employer.

Conclusions

The absence of statistically significant relationships between demographic and practice profile variables, other than gender identity, suggests that the other factors identified in the literature as risks to competence and professional conduct, are not necessarily risk factors for how registrants complete their CCLP submissions. Further comparison of CCLP submission ratings to other workplace and personal factors is required to identify those that may be useful for risk-based selection for CCLP submission review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Developing and implementing programs for monitoring and assessing the continuing competence of regulated health professionals (registrants) is one way that regulators of health professionals promote and protect the public interest. The intent of programs that require health professionals to demonstrate their ongoing competence in practice is to ensure that health professionals are providing ethical, effective, and safe health services throughout their careers [1,2,3,4].

Regulators use different terms to describe programs or processes for continuing competence, including continuing education, continuing professional development, and quality assurance [1,2,3,4]. The most common approaches used by regulators for monitoring registrant continuing competence include completion of a minimum number of practice hours or professional development in a specified time frame, and/or completion of electronic or paper-based competence portfolios. Such portfolios may require a self-assessment to identify learning goals, written descriptions or proof of activities undertaken to achieve learning goals, and reflecting on how participation in the learning activities has helped to achieve learning goals and enhance professional practice [1,2,3].

Competence assessment is another approach used by regulators as a means of ensuring their registrants are providing ethical, effective, and safe services. Terms used for competence assessment include audits, practice reviews, practice visits, revalidation, recertification, and quality management [1]. Direct competence assessment is known to be the most reliable and valid means of competence assessment. Examples of direct assessment include direct observation of practice, clinical simulation, objective structured clinical exams, clinical knowledge or jurisprudence exams, facilitated feedback sessions, structured interviews, and chart stimulated recall [1, 5]. Indirect competence assessment is less evidence-based. Examples of indirect competence assessment include audits of hours spent undertaking professional development activities, audits of the type of professional development activities undertaken, rating and/or provision of feedback on competence portfolios, peer review of practice, reviews of employer performance appraisals, and/or reviews of client charting/records [1, 2].

Few regulators implement programs for competence assessment due to the extensive resources needed for implementation [1, 6]. Small or mid-size regulators often rely solely on their continuing competence programs to meet legislated requirements due to resource limitations and implementation challenges associated with competence assessment programs [2]. If indirect assessment of competence is used by these smaller regulators, they lean towards selection of a small percentage of registrants for assessment—either random selection or selection based on risks [1, 6, 7]. Risk-based selection for competency assessment may be done based on risks already identified in the literature including risks for complaints of unprofessional conduct or malpractice claims [8,9,10], risks to reflective practice [11], and/or risks to competence [12].

A rapid evidence synthesis exploring the continuing competence and competence assessment programs used by regulators noted a shift by regulators to adopt reflective practice or practice/quality improvement approaches [2]. However, there is limited research to date to identify the most effective programs for accurately measuring registrants’ ongoing competence in practice [1,2,3,4, 13]. This study aims to contribute to the research evidence by reporting the findings from an evaluation of the program for monitoring and assessing continuing competence used by a mid-sized regulator (~ 2300 registrants) of occupational therapists in Alberta, Canada.

1.1 Study context

The program for continuing competence used by the Alberta College of Occupational Therapists (the College) is a reflection-based, online continuing competence portfolio submitted by registrants as a mandatory requirement of annual practice permit renewal. The portfolio has two main components:

-

Continuing Competence Self-Reflection—where a registrant reviews the College's practice standards and code of ethical conduct and considers which indicators align with their learning goals. Registrants must select at least one and up to three goals in their annual continuing competence learning plan.

-

Continuing Competence Learning Plan (CCLP)—where a registrant records their learning goals identified in the self-reflection and specifies why they selected it as a goal. Throughout the year, they describe and reflect on the activities completed to achieve their goals. Registrants provide a summative reflection on how engaging in the learning activities maintained or enhanced their competence.

Reflection is the structured, purposeful, critical analysis of one’s own knowledge and experiences to identify opportunities for growth with the goal of improving practice [14, 15]. Reflective practice is known to be a key aspect of competence [5, 12], and promotes active learning [16]. It has also been associated with improved competence in practice [17, 18], particularly when the reflections are documented in a written format [19,20,21].

The program for competence assessment used by the College is the review and rating of a selected number of CCLP submissions as part of the annual CCLP review process. The purpose of the review process is two-fold; both individual and program level. The individual-level review aims to provide feedback to registrants about the content of their CCLP submission and if it adequately captures their commitment to reflective practice and continuous learning according to the CCLP review rubric [22]. Feedback is offered to registrants who do not meet the expectations for an acceptable CCLP submission to support them in future submissions. Registrants who do not meet the expectations for an acceptable CCLP submission one year, are selected for re-review in the following year. Additional indirect or direct methods of competence assessment are considered if a registrant’s submission does not meet requirements two years in a row.

The program level review aims to analyze CCLP submission ratings and compare them to the demographic, practice profile, and submission content variables for each registrant selected for individual-level review. The intent of the program-level review is to analyze findings to identify trends in CCLP submissions and act on those trends as needed (i.e., provision of additional targeted supports and resources for registrants, shift from random to risk-based selection of CCLP submissions for review).

1.2 Study aim

With two years of CCLP review data gathered and available for analysis, this evaluation study aims to gather evidence to answer the following three questions:

-

1.

What percentage of registrants complete their CCLP submissions according to the College’s expectations each year?

-

2.

Have the additional resources and training offered had an impact on the quality or quantity of reflective content in CCLP submissions?

-

3.

Are there any demographic or practice profile variables associated with overall submission rating or submission content variables that could be used to justify a shift to risked-based selection of CCLP submissions by the College?

A final overarching question, which ties back to the conclusions drawn in systematic and scoping reviews undertaken over the years [1,2,3, 13] is:

-

4.

Do the answers gleaned from the preceding questions offer sufficient evidence to indicate that the programs for continuing competence and competence assessment used by the College are effective in assuring that registrants are competent in actual practice?

2 Methods

2.1 Study population

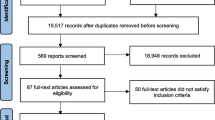

Occupational therapists registered with the College during the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 registration years were included in the randomized selection for review of their CCLP submissions. Registrants were removed from the randomized list if they were not registered at the time CCLP submissions were reviewed due to retirement, leave of absence, or moving to another province or country. Registrants whose submissions were reviewed and received an acceptable rating in 2021 were excluded from randomization in 2022.

2.2 Sampling

A randomized sample of ten percent of registrants’ CCLP submissions were selected from the registrant database for review in 2021 (n = 229) and 2022 (n = 238). Forty-one registrants were directly selected for re-review in 2022, bringing the total number of submissions reviewed in 2022 to 279.

2.3 Data collection

Data were reviewed for completeness and accuracy and anonymized prior to sharing with the analysis team. The demographic and practice profiles of the registrants selected for CCLP review and evaluation were compared to the distribution of demographic and practice profiles of the full population of registrants to see if the distributions had similar representation across variables.

2.4 Variables

The ten members of the Continuing Competence Committee reviewed and rated the content of de-identified CCLP submissions based on the criteria outlined in the CCLP review Rubric [22] (see Table 1 in supplemental materials). A rating of “Acceptable” (with gradations of ‘Exceeds Expectations’, ‘Meets Expectations’, and ‘Almost There’), “Conditional” or “Not Acceptable” was assigned to each submission based on a reviewer’s overall impression of the content in the registrant’s CCLP. Details on the development and testing of the rubric used, the training of reviewers, and processes for ensuring interrater reliability, are published as a public report, Continuing Competence Program Review and Evaluation 2021 [23].

CCLP submission content, demographic, and practice profile variables (see Table 2 in supplemental materials) were retrieved from the registrant database and added to the submission rating dataset for inclusion in the analysis. For registrants with more than one employer, the employer the registrant practiced the most hours with was considered the primary employer and used in data collection. Geographic location of practice was collected for the 2022 review only.

2.5 Data analysis

The data from the participants in 2021 (n = 229) and 2022 (n = 279) were analyzed separately. After excluding re-reviews in the second year (n = 41), 467 participants were included in the dataset for a combined analysis.

Descriptive statistics were conducted using StataIC 15 [24] to describe CCLP submission ratings, content factors, demographic profiles, and practice profiles of the participants included in the study. Frequency (n and %) of CCLP ratings and content factors were calculated for both years. This step included a comparison of year-to-year CCLP ratings and content variables for those whose submissions were re-reviewed due to Conditional or Not Acceptable ratings in the previous year.

Pearson chi-squared tests were conducted to determine if there was a relationship between different demographic and practice profile variables and CCLP submission ratings. Categories of reviewer ratings (Table 1 in supplemental materials) and demographic and practice profile variables (Table 2 in supplemental materials) were grouped for ease of presenting the descriptive results and to increase cell frequencies to run chi-square analyses. Alpha level was set at p < 0.05 to determine statistical significance of findings.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Descriptive results for the CCLP ratings and submission content variables are presented in Table 3 (see Table 3 in supplemental materials). The majority of CCLP submissions (79.9%) were considered Acceptable. The majority of submissions included reflective content (54.4%) and ≥ 4 sentences in each CCLP section (52.5%). Most participants (44.1%) identified two learning goals. An average of 3.7 learning activity records were identified in the CCLP submission, with 60.4% of the participants including one to three. After removing two outliers, the mean self-reported overall time spent completing CCLP learning activities was 52.1 h with 60.0% of participants reporting they spent ≤ 30 h. Due to lack of instruction provided to registrants about how to count and report time spent in learning activities, findings from the analysis of this variable should be interpreted with caution.

Year-to-year comparisons show a 2.4% increase in the percentage of CCLP submissions rated as Acceptable (2021—78.6%; 2022—81.0%), with the most noticeable increase (12.8%) being in the Meets Expectations rating (2021—34.5%; 2022—47.3%). There was a statistically significant change in the quality of written content in the CCLP submissions reviewed in 2022, with 15% more submissions rated as having reflective content in 2022 (2021—46.7%; 2022—61.7%; p < 0.5). There were also fewer submissions rated as having vague or superficial content (2021—19.7%; 2022—9.3%). Of the 41 registrants selected for re-review in 2022, 85.4% had improved ratings. However, 12.2% received the same rating and 2.4% received a lower rating (Table 3 in supplemental materials).

Descriptive results for the demographic and practice profile variables of the participants are reported in Table 4 (see Table 4 in supplemental materials). The participants were predominantly women (91.2%), with a mean age of 41.7 years. The mean years since graduation was 16.7 years, with 34.1% having graduated within the past 11–20 years. The majority of participants (86.5%) worked in a direct clinical service role, with most working with clients over the age of 18 years (53.1%) in either continuing care (28.1%) or hospital (27.2%) settings. Geographic location was only collected for 2022, with the majority of participants (88.9%) having a primary employer based out of an urban setting (Table 4 in supplemental materials).

The distributions of demographic and practice profile variables of the randomly selected sample in this study closely mirror the distributions of the same variables in the full population of registrants. One slight difference (less than 2%) was noted in the distribution of gender identity. The percentage of women in the general population of registrants is lower than the percentage randomly selected for CCLP review (89.5% versus 91.2%). The percentage of registrants identifying as other (non-binary, transgender, or two-spirit) is only slightly lower in the general population of registrants (0.2% versus 0.4%) and the percentage of registrants identifying as men in the general population is higher (10.3%) than the percentage of men selected for CCLP review (8.4%).

3.2 Correlations

Statistically significant associations were found between submission content ratings and submission content variables (see Table 5 in supplemental materials). The quality (reflective) and quantity (≥ 4 sentences per CCLP section) of written content, and the submitted number of learning activity records (more than three) were associated with ratings of Meets and Exceeds Expectations.

The only statistically significant association observed between CCLP submission rating and demographic or practice profile variables was with gender identity (see Table 6 in supplemental materials). Participants identifying as men were more likely to receive ratings of Needs Improvement (either Conditional or Not Acceptable) compared to participants identifying as women or non-binary (38.5% for men versus 18.5% of women and 0% of non-binary persons, p = 0.04). There was no association between years since graduation, client age range, practice area, practice role, practice setting, or geographic location of the primary employer with CCLP submission rating.

Additional correlation analyses were conducted to observe any associations between gender identity and CCLP submission content variables (see Table 7 in supplemental materials). There was a statistically significant association between gender identity and the quality of written content with women more likely to include reflective content (55.2% versus 50% of non-binary persons, and 46.2% of men). Also, non-binary participants were less likely to include vague or superficial content (0% versus 12.7% of women, and 35.9% of men). There were no statistically significant associations between gender identity and other variables for CCLP submission, including average length of written content or number of learning activity records added (Table 7 in supplemental materials).

A statistically significant difference in the number of CCLP submissions with reflective content was observed when comparing the quality of written content between the two years (Table 3 in supplemental materials).

4 Discussion

4.1 CCLP submission quality

The high percentage of CCLP submissions being rated as acceptable (almost 80%), and the significant change in the number of submissions with reflective content between 2021 and 2022 (15% more submissions included reflective content in 2022; p < 0.5) are notable findings which could be related to the type and amount of support provided to registrants. The resources prepared to help registrants to complete satisfactory CCLP submissions in the 2020–2021 registration year focused primarily on navigation of the electronic CCLP forms rather than on how to reflect on the impact of participation in learning activities. Preliminary findings from the 2021 review flagged a need to expand the types of resources offered to registrants and incorporate a greater focus on the ‘why an activity was chosen’ and ‘how the learning activities impacted practice’ aspects of reflective practice. In 2022, brief (15–30 min), interactive, group-based, mentoring sessions started—increasing in frequency of offering as the deadline for permit renewal approached. The mentoring sessions included discussions about the theory of reflective practice, gave examples of acceptable CCLP submissions for attendees to view, and offered an opportunity for attendees to ask questions. Providing active rather than passive support has been identified as an important strategy for registrants to understand the value of reflecting on and writing about their practice [16, 25]. The significant increase in the number of submissions with reflective content between 2021 and 2022 suggests that these mentoring sessions were impactful.

The percentage of Not Acceptable and Conditional submissions rated higher on re-review (85.4%) is likely related to the written feedback provided by reviewers and the guidance provided by college staff in the structured coaching sessions. Giving detailed and constructive feedback on content included in competence portfolios helps to improve registrants’ perceptions of reflection-based competence portfolios [16,17,18,19,20,21, 25, 26].

4.2 Relationship of CCLP submission ratings and content variables

Although the CCLP review rubric [22] is designed to give higher ratings to CCLP submissions with reflective content, there is no added credit given to CCLP submissions that include more written content, more learning activity records, or more self-reported time spent in learning activities. However, a pattern of ‘more is better’ became clear in the analysis. Participants who included more written content (i.e., ≥ 4 sentences per section) were more likely to have their CCLP submission rated as Meets or Exceeds Expectations. Participants with ratings of Meets or Exceeds Expectations also included more learning activity records.

Another aspect of quantity is the time spent taking part in learning activities. In a recent systematic review conducted by Main and Anderson [4], no evidence was identified to answer the research question “Is there evidence to support an optimal quantity of continuing professional development to maintain competence?” [4, p.4] The lack of instruction on how to report time spent in learning activities in a CCLP submission led to broad variation and inconsistency in reporting by registrants, making the interpretation of findings challenging. It is interesting to note though that 39.3% of participants whose submissions received a rating of Pass (Meets or Exceeds Expectations) reported spending ≤ 20 h in learning activities in the year. On the other hand, the same percentage (39.3%) of those whose submissions received a rating of Needs Improvement (Conditional or Not Acceptable) reported spending ≥ 20 h in learning activities in the year (with 20.2% of those reporting spending > 51 h per year) (Table 5 in supplemental materials). In the case of this study, this observation does not necessarily show an optimal quantity of learning activities or continuing professional development. Rather, it shows that registrants who spend a significant amount of time in learning activities, may not always convey in writing how those learning activities have maintained or enhanced their competence in practice. This observation requires further exploration to determine the optimal quantity of competence activities for maintenance of competence.

4.3 Relationship of CCLP submission ratings, demographic, and practice profile variables

This study identified a statistically significant relationship between CCLP submission rating, quality of written content and gender identity (Table 6 in supplemental materials). Participants identifying as women or non-binary were more likely to include reflective content and thus have their CCLP submissions rated as Acceptable. This finding is contrary to Mamede and Schmidt [11] who investigated the relationship between reflective practice and gender identity and observed no significant association with identified gender and reflective practice.

With the extensive research identifying demographic and practice profile factors as risks to competence and complaints [8,9,10,11,12], the absence of relationships between CCLP rating and the remaining demographic and practice profile factors analyzed in this study is worth noting. It suggests that risk-based selection for review and evaluation of CCLP submissions, based on demographic and practice profile alone, may not be useful for regulators who adopt a reflection-based approach to their continuing competence programs.

4.4 Reflective practice as an effective indicator of competence

Drawing a direct line of association between the reflective content in a CCLP submission and reflective practice or competence in practice is challenging. This is mostly due to the reliance on self-reported change rather than direct observation of performance [2, 3, 16]. Eva et al. [6] also reported that “when the stakes are high and momentary, however, even one’s personal ‘reflections’ can become fictional when the system encourages them to be written for external review.” [6, p.10] However, there is growing evidence to suggest that an indirect line from a health professional’s capacity for reflective practice can be drawn [17,18,19,20,21]. Researchers propose that this indirect line is possible due to the critical thinking and reasoning skills that reflective practice and reflective writing require [5, 15, 17, 18].

Triangulating the CCLP submission ratings with evaluation of the randomly selected registrants’ actual performance in practice would be a more definitive way to confirm the effectiveness of the College's continuing competence program. Currently, only those registrants with CCLP submissions rated as Not Acceptable two years in a row are selected for additional competence assessment (i.e., review of workplace performance appraisals and client records). It would be valuable to undertake further competence assessments with registrants with different ratings of CCLP submissions. Reviewing the CCLP submissions of registrants who have undergone investigation for complaints of unprofessional conduct could also be helpful in identifying any patterns in CCLP ratings or content variables for those individuals.

4.5 Study limitations

This study evaluates the specific approaches for continuing competence and competence assessment used by a mid-size, single-profession regulator (~ 2300 registrants) in Alberta, Canada, and may not be generalizable to larger, multi-profession regulators whose approaches or legislated requirements for continuing competence or competence assessment may vary. Findings may also not be generalizable to regulators whose registrant population has different gender ratios.

5 Conclusions and directions for future research

The enhanced continuing competence resources prepared, including the addition of reflective practice mentoring sessions, appears to have had a positive impact on the percentage of submissions with reflective content and improved ratings year-over-year. The sessions offer registrants opportunities to learn more about the value of reflective practice and its connection to competence in practice. Given that men were more likely to include vague or superficial content, targeted supports or identification of peer mentors identifying as men may be beneficial.

The absence of statistically significant relationships between demographic and practice profile variables except gender identity suggests that the factors known to be risks to competence and professional conduct found in the literature, are not necessarily risk factors for how registrants complete their CCLP submissions. Further exploration into other workplace and psychosocial variables including work-life balance, hours worked per week, job demands, job control, personality style, and life satisfaction [9] could be a next step for the program-level review, as these factors may be stronger influences on a registrant’s ability to reflect on and write about practice.

Further evaluation of reflection-based continuing competence programs is needed to determine the effectiveness of this approach more accurately. Incorporation of additional indirect and direct approaches to competence assessment, to triangulate with the CCLP ratings across the range of ratings, may aid in drawing the line from reflective content in a CCLP submission to competence in practice. In addition, a retrospective review of the CCLP submissions of registrants investigated for complaints could be helpful in identifying any relationship between CCLP rating and content and risk of complaints.

Data availability

The dataset is available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Austin Z, Gregory PAM. Quality assurance and maintenance of competence assessment mechanisms in the professions: a multi-jurisdictional, multi-professional review. J Med Regul. 2017;103(2):22–34. https://doi.org/10.30770/2572-1852-103.2.22.

Bullock A, Kavadella A, Cowpe J, Barnes E, Quinn B, Murphy D. Tackling the challenge of the impact of continuing education: an evidence synthesis charting a global, cross-professional shift away from counting hours. Eur J Dent Educ. 2020;24(3):390–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12514.

Karas M, Sheen NJL, North RV, Ryan B, Bullock A. Continuing professional development requirements for UK health professionals: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3): e032781. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032781.

Main PAE, Anderson S. Evidence for continuing professional development standards for regulated health practitioners in Australia: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2023;21(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-023-00803-x.

Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;287(2):226–35. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.2.226.

Eva KW, Bordage G, Campbell C, Galbraith R, Ginsburg S, Holcombe E, et al. Toward a program of assessment for health professionals: from training into practice. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016;21:897–913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-015-9653-6.

College of Occupational Therapists of Ontario. Competency Assessment—Risk Based Selection. Accessed from https://www.coto.org/registrants/quality-assurance/competency-assessment. Accessed 30 April 2023.

Austin EE, Do V, Nullwala R, et al. Systematic review of the factors and the key indicators that identify doctors at risk of complaints, malpractice claims or impaired performance. BMJ Open. 2021;11: e050377. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050377.

Bradfield OM, Bismark M, Scott A, Spittal M. Vocational and psychosocial predictors of medical negligence claims among Australian doctors: a prospective cohort analysis of the MABEL survey. BMJ Open. 2022;12: e055432. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055432.

Spittal MJ, Bismark MM, Studdert DM. Identification of practitioners at high risk of complaints to health profession regulators. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:380. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4214-y.

Mamede S, Schmidt HG. Correlates of reflective practice in medicine. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2005;10(4):327–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-005-5066-2.

Glover Takahashi S, Nayer M, St Amant LMM. Epidemiology of competence: a scoping review to understand the risks and supports to competence of four health professions. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014823. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014823.

Myers CT, Schaefer N, Coudron A. Continuing competence assessment and maintenance in occupational therapy: scoping review with stakeholder consultation. Aust Occup Ther J. 2017;64:486–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12398.

Bannigan K, Moores A. A model of professional thinking: integrating reflective practice and evidence based practice. Can J Occup Ther. 2009;76(5):342–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740907600505.

Epstein RM. Reflection, perception, and the acquisition of wisdom. Med Educ. 2008;42(11):1048–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03181.x.

Zaccagnini M, Miller P. Portfolios with evidence of reflective practice required by regulatory bodies: an integrative review. Physiother Can. 2022;74(4):330–9. https://doi.org/10.3138/ptc-2021-0029.

Ratelle JT, Wittich CM, Yu RC, Newman JS, Jenkins SM, Beckman TJ. Relationships between reflection and behavior change in CME. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2017;37(3):161–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000162.

Paterson C, Chapman J. Enhancing skills of critical reflection to evidence learning in professional practice. Phys Ther Sport. 2013;14:133–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2013.03.004.

Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14:595–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2.

Wald HS, Borkan JM, Scott-Taylor J, Anthony D, Reis SP. Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):41–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823b55fa.

Artioli G, Deiana L, De Vincenzo F, Raucci M, Aramducci G, Bassi MC, Di Leo S, Hayter M, Ghirotto L. Health professionals and students’ experiences of reflective writing in learning: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:394. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02831-4.

Alberta College of Occupational Therapists. Continuing Competence Program (CCP) Review and Evaluation Rubric (2021). https://acot.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2020/12/CCP-Submission-Rubric-June-2021-1.pdf. Accessed 17 March 2023.

Alberta College of Occupational Therapists. Continuing Competence Program (CCP) Review and Evaluation 2021 (2021). https://acot.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Continuing-Competence-Program-Review-2021.pdf. Accessed 17 March 2023.

Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. StataCorp. 2015.

Vachon B, Rochette A, Thomas A, Desormeaux WF, Huynh AT. Professional portfolios used by Canadian occupational therapists: how can they be improved. Open J Occup Ther. 2016. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1280.

Colquhon HL, Carrol K, Eva KW, Grimshaw JM, Ivers N, Michie S, Brehaut JC. Informing the research agenda for optimizing audit and feedback interventions: results of a prioritization exercise. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01195-5.

Acknowledgements

Anna Yarmon and Judith Pinto helped with manuscript review and copy edits.

Funding

Data analysis and assistance with preparation of the manuscript was completed by the two authors from the University of Alberta Rehabilitation Research Centre (PF and DG) on contract with the Alberta College of Occupational Therapists.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AF, AM, and MB collected the data. AM cleaned and de-identified the dataset. PF conducted the data analysis and DG assisted with interpretation of the findings. AM and PF were major contributors in drafting and reviewing the manuscript. AF, MB, and DG reviewed drafts of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This evaluation study was conducted with data collected by the Alberta College of Occupational Therapists as required by the Health Professions Act (HPA) section 33(3) and 33(4). Participant data used in this study was de-identified, shared and analyzed in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Alberta Health Ethics Review Board (UofA HERB). The ethical standards of the UofA HERB align with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The study and a waiver of consent was approved by the UofA HERB on July 29, 2022 (Pro00121977).

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meneley, A.R., Firouzeh, P., Ferguson, A.F. et al. Evaluation of a reflection-based program for health professional continuing competence. Discov Health Systems 2, 41 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-023-00058-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-023-00058-2