Abstract

Background

Modern digital technologies are actively being introduced into spheres of society, including justice. Electronic justice at the present stage of development of information technology has moved to a qualitatively new level. It has become obvious that artificial intelligence (AI) is our present, not our future.

Objective

This article analyzes foreign experience in the implementation and use of AI in justice, identifies possible areas for the use of AI in justice, examines the legal personality of AI and the scope of its competence, and evaluates the prospects for the development of AI in justice.

Results

The authors identified the following areas of use of AI in justice: organizational sphere of activity of courts; assessment of evidence and establishment of legally significant circumstances; consideration of the case by AI. Also in this study, the stages of introducing AI into justice: short-term perspective, medium-term perspective (5–10 years), long-term perspective. It is noted that at present the work of AI is possible only in conjunction with a human judge.

Conclusions

The authors noted the feasibility of using AI in resolving issues that require processing a large amount of information and documents in electronic form. This will ensure procedural savings and reduction of time for consideration of disputes on the merits through speed and error-free calculations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The development of digital justice in Russia is a priority task for the state, the solution of which is aimed at increasing confidence in the judicial system, including in conditions of digital inequality [11, 39]. AI technologies and products are used in many spheres of society, and we no longer notice the difference between the material world and augmented virtual (artificial) reality, mixing or identifying them. Artificial intelligence is a set of technological solutions that makes it possible to imitate human cognitive functions (including self-learning and searching for solutions without a predetermined algorithm) and obtain results when performing specific tasks that are comparable, at a minimum, to the results of human intellectual activity. The set of technological solutions includes information and communication infrastructure, software (including those that use machine learning methods), processes and services for data processing and finding solutions.

AI, as an effective tool used in the legal process, has been actively discussed in legal studies in recent years [1, 27,28,29,30]. Thus, modern researchers (Biryukov [5], Kolokolov [22], Neznamov [38], Zhi [21], Surden [48], etc.) indicate that the judicial system cannot ignore the achievements of scientific and technological progress, and AI is becoming one of the full-fledged participants in the administration of justice; moreover, its introduction into the judicial system is already inevitable.

However, some scientists have expressed concerns about the use of AI in justice. Thus, the use of AI in justice entails the need to ensure access to sensitive data, including personal data. At the same time, today no system (including government) can ensure data security when using AI technologies [44].

It is also suggested that making a decision based solely on an algorithmic assessment of circumstances and evidence will lead to a violation of the constitutional rights of citizens to a fair trial [51]. However, one can agree with this position only if the parties, firstly, are deprived of the opportunity to raise objections to the conclusions of the AI, and secondly, the decision made is not subject to appeal.

The advantages of the algorithmic work of AI ensured the future of its development and inevitable use in court. Possible shortcomings in the operation of AI discussed by legal scholars and engineers have not become an obstacle to its implementation in courts.

Considering the large number of cases, the use of AI has great potential to support judicial activities, which will ensure greater access to justice, transparency and accountability, and lead to lower costs and shorter trial durations [41, 47]. For example, a fairly large number of court cases are simple and standard disputes (if not identical) with a predictable effect. Using AI to automate the decision-making process in such disputes will lead to a reduction in the number of litigations, and as a result, lower costs [18, 41, 45,46,47]. In addition, such automation will provide judges with more time to review and resolve more complex cases.

Another undoubted advantage is that AI is never affected by human factors such as fatigue or emotional stress. The operation of AI is ensured by an appropriate processor, computer program and electrical energy. For AI to fully operate, access to the Internet telecommunications network is also required. The existing technological risks of AI failure, including due to lack of access to the Internet, can be compensated, for example, by creating autonomously operating databases in the “judicial cloud” and constantly updating them.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 3.1 explains international experience in using AI in justice (China, USA, UK and Russia). The areas of use of AI in justice (organizational sphere of activity of courts (registration of cases, formation of the court composition, recording, etc.); assessment of evidence and establishment of legally significant circumstances; consideration of the case by AI) are described in Section 3.2. Section 4 contains information about the results of the research. Conclusions are given in Section 5.

2 Materials and Methods

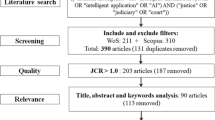

The information base of the research consists of 57 sources, including various regulations on AI, legal research, thematic publications in the media and Internet sources.

General scientific empirical methods were observation (of the progress of development of AI technology and areas of application in justice), comparison (of the effectiveness of AI and employees of the judicial system), material modeling (of the real work of AI in the field of justice). Theoretical research methods were also used: analysis (of the advantages and disadvantages of AI), mental modeling (of the prospects and areas of possible application of AI in justice).

3 Discussion

3.1 International Experience in Using AI in Justice

3.1.1 China

The integration of AI into the Chinese judicial system has been ongoing since 1990. Thus, the transformation of China's judicial system took place in three stages [47]. The first phase began after the “National Conference on Judicial Communication and Computers” in 1996 (“1996 Conference”) and ended in 2003 when all courts in China completed the digitization of their files and website links. The second stage of transformation of China's courts took place between 2004 and 2013 and was characterized by the conduct of court hearings using the Internet. For example, in a divorce case, a local court in Guangdong Province in southern China communicated with an overseas defendant via email, and also served documents and exchanged materials that way [9]. The first full hearing via videoconferencing in China took place in 2007 in a criminal theft case in Shanghai [34]. During this period, judicial openness was facilitated by the live broadcast of court hearings to the public. For example, in September 2009, the Beijing Supreme People's Court announced that, in order to promote justice and enable people to monitor court proceedings, it had created a Beijing-wide website with live coverage of court hearings, where the general public throughout the country had simultaneous access to monitor court proceedings hearings held in any court in the Beijing area [10].

In 2014, Chinese courts entered the third stage of transformation with the introduction of the "smart courts" initiative, which supported the use of more sophisticated technologies. Thus, according to the concept of “smart court”, it is assumed that all court services are available and carried out online [49]. As part of this stage of transformation, work on the following online platforms was completed: China Judicial Process Information Online, China Judgments Online and China Judgments Enforcement Information Online.

In addition to these platforms, a special type of court called “Internet Court” has been created in China. The Internet Courts of Beijing, Guangzhou, and Hangzhou have jurisdiction to hear a number of cases related to the Internet, such as disputes over online payments in online stores, the provision of Internet services, domain names of websites, liability for content posted on the Internet information that violates human or public rights, in case of copyright infringement on the Internet (Hangzhou Internet Court). Using the web platform "Hangzhou Internet Court Litigation Platform", all legal proceedings can be completed online (from filing a case and serving court documents to exchanging and examining evidence, online hearing and adjudication), however, in some In cases (if necessary), the court may switch to the in-person format of the trial.

Also, since March 2019, Chinese citizens have the opportunity to resolve online disputes through the popular WeChat messenger, which recognizes the face of a participant in the process to establish identity and allows the use of an electronic signature when submitting statements and evidence. The process takes place in video chat format, and the decision is made by AI.

In September 2019, the Beijing Internet Court released a White Paper on the Application of Internet Technologies in Judicial Practice [40], which included provisions for the creation of an "intelligent online court". Thus, this document described how courts use various technologies (mainly related to AI) in the administration of justice, including facial recognition technology to confirm the identity of the parties, as well as machine learning technology to automatically make court decisions [56]. Blockchain technology has been used in Internet courts for the purpose of preserving evidence, and in 2018, the Hangzhou Internet Court became the first court in China to recognize blockchain technology as a means of storing evidence to aid in copyright infringement cases.

A pilot program has been launched in Shanghai and a number of other regions of China, which, based on the use of a large array of data contained in verdicts in previous cases, helps judges understand the issue of proof of charges and suggests the optimal type and amount of punishment. AI recognizes speech, identifies contradictions in testimony, as well as written evidence, and alerts the judge about it. The algorithm analyzes information about the defendant’s personality and, comparing it with data contained in other sentences, proposes the punishment that judges most often impose in similar circumstances. This makes it possible to unify justice in a country with the largest population and number of judges (more than 100 thousand) in the world [32].

Thus, it can be noted that in China, AI technology does not replace the judge, but only helps him in analyzing cases and making decisions, including determining relevant laws and precedents. However, AI technology is used by Chinese judges not only to administer justice, but also to conduct legal research. For example, China's Supreme People's Court has developed an AI-powered legal research platform called China Judgments Online, which allows judges to quickly search and access relevant legal documents.

3.1.2 United States of America

Currently, the main US regulatory act in the field of AI is the National Artificial Intelligence Initiative Act of 2020, according to the provisions of which the initiative in the field of AI should ensure the continued leadership of the United States in the field of research and development of AI, maintaining the US leading position in the world with regard to the development and use of reliable AI systems in the public and private sectors. It also notes the need to prepare the current and future American workforce to integrate AI systems across all sectors of the economy and society.

The use of AI technology in the judicial sphere seems to be very popular in the United States, which has freely invested money in the development of this technology in both civil and criminal proceedings. Thus, in the United States, several initiatives related to the use of AI in justice have been implemented.

The main purpose of AI is to help judges make fair and unbiased decisions, as well as assess the risks when making a decision. For example, the PSA (Public Safety Assessment) system is used by judges when making decisions on choosing a preventive measure against the accused (real or suspended sentence), on early release and on determining the amount of bail. The following system, COMPAS (Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions), assesses the risk of reoffending on a scale of 1 to 10. Based on its recommendations, judges make decisions on measures of restraint and parole. With values from 1 to 4, the risk is determined to be insignificant, and the suspect (convicted) goes free. At higher values, judges make decisions, as a rule, not in favor of the prosecution. The assessment is carried out based on the analysis of personal data on 137 factors, such as gender, age, education, criminal record, social environment, etc. Based on this assessment, the system provides a forecast of the likelihood of a suspect (convict) committing a recidivism. Thus, this system helps judges determine fair punishment for various crimes.

However, as practice has shown, this system is imperfect. According to a study by the nonprofit Pro-Publica, the system was twice as likely to predict recidivism for Blacks as it was for whites, and was just as likely to make unfavorable predictions for Blacks and favorable predictions for whites [2]. Such an error is not due to an incorrect formula for calculating the probability of relapse, but to the criteria that the system developers put into this algorithm, as well as a data sampling error. Thus, it can be stated that AI is not devoid of bias in decision making.

The next system based on AI technology is Ravel Law. This system allows you to determine the outcome of a case based on relevant precedents, judges' decisions and reference statements from more than 400 courts. This has allowed lawyers, in combination with other AI applications, to have a very real and pragmatic picture of the likelihood of success of certain legal arguments in certain courts and before certain judges depending on the type of case.

Also in the United States, AI-powered chatbots (such as ROSS) have been created to provide the public with information about common issues related to the judicial system, thereby reducing the burden on court staff and ensuring public access to information.

3.1.3 United Kingdom

In November 2022, the House of Lords published a report by the Justice and Home Affairs Committee, which reviewed the use of AI technologies in the UK criminal justice system [6]. The unregulated use of AI in the UK justice system is potentially leading to miscarriages of justice, according to this report.

Durham Police, together with the University of Cambridge, have developed the Harm Assessment Risk Tool (HART) [7], which, based on the analysis of 34 indicators, predicts the likelihood of an offender committing a repeat offense. To prevent racial disparities, HART's developers did not include race in the predictors used by the algorithm. Unlike the American COMPAS system, this algorithm was used to inform police officers about the selection of candidates for a rehabilitation program, and not to decide on a preventive measure and on parole.

AI technologies are also used by Kent Police to predict the location of a future crime (PredPol system). The system learns by analyzing data from past crime locations and uses it to identify areas where police may be needed.

However, British officials are quite skeptical about the use of automated systems for decision-making, since they believe that the appropriate and final decision should be made by a person, and not by AI. In addition, the Committee noted the lack of minimum standards, transparency, assessment and training in AI technologies and concluded that this could lead to violations of human and civil rights and freedoms. In this regard, the Committee developed the following recommendations: mandatory training in the use of AI, the creation of a national body in the field of the use of new technologies, the development of general and special legislation providing for general principles and standards for the use of AI.

In the UK, in addition to the systems discussed, the Digital Case System (DCS) has been developed and used, an electronic platform that the United Kingdom Ministry of Justice introduced in 2020 for the management of cases in the Royal Court. Designed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the criminal justice system in England and Wales, DCS enables judges, lawyers and other court staff to manage cases digitally from start to finish.

DCS serves two primary functions: it allows you to access and update filed cases in real time, and it allows you to participate remotely in court proceedings. In addition, the system allows parties to submit evidence and documents digitally, reducing the amount of paper used in court proceedings. The UK Bar Council's Ethics Committee issues guidance from time to time to assist criminal defense practitioners across the country in accessing the online portal.

3.1.4 European Union

Legal regulation of the use of AI technology in justice is based on the following documents. These include, firstly, the Ethical Charter on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Judicial Systems and their environment, adopted by the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) on December 3, 2018 [15]. This document provides five basic principles for the use of AI in justice:

-

The principle of respect for fundamental rights (AI should not interfere with the exercise of the right of access to justice and the right to a fair trial);

-

The principle of non-discrimination;

-

The principle of quality and safety (data loaded into AI must be interdisciplinary, obtained from certified sources and capable of being accumulated and executable in a safe environment that ensures the integrity and inviolability of the system);

-

The principle of transparency, impartiality and reliability (full technical transparency of AI and providing access to the development process, absence of bias and the possibility of external audit);

-

The principle “under user control” (ensuring at any time the possibility of reviewing judicial acts and data used to obtain the result (a binding decision is made not by AI, but by a judge), as well as guaranteeing the right of a person participating in the case to have the dispute considered directly by the court).

Thus, it can be noted that the provisions of this Charter do not allow decision-making on a dispute solely by AI, but provide for the possibility of using AI in justice as an assistant judge.

The next document is the Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, approved by the European Commission in 2019. Trustworthy AI has three components, which should be met throughout the system's entire life cycle: (1) it should be lawful, complying with all applicable laws and regulations (2) it should be ethical, ensuring adherence to ethical principles and values and (3) it should be robust, both from a technical and social perspective since, even with good intentions, AI systems can cause unintentional harm. According to the provisions of this document, the main ethical principles for the use of AI are: respect for human autonomy, prevention of harm, fairness and explicability.

In addition, the EU has adopted the Digital Europe Strategy Programme as a systemic component of the EU financial consolidation for 2021–2027 to digitalise European society and maintain competitiveness in innovative technologies, including robotics and AI technologies [52]. The main objective of this programme is to stimulate digital transformation by providing funding for the implementation of emerging technologies in the most important areas, each with its own budget, including high performance computing, AI, cyber security and trust, high level of digital literacy, implementation and optimal use of digital literacy.

At the end of April 2021, the European Commission published a draft of the world's first law to regulate in detail the development and use of systems based on AI Laying down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain union legislative acts [31]. The main objectives of this bill are:

-

1)

To establish a legal framework guaranteeing the safety and compliance with European law of AI systems entering the EU market;

-

2)

To provide a legal environment for investment and innovation in the field of AI;

-

3)

To establish an enforcement mechanism in this area.

In the same bill, the EU proposes a risk-based approach to the regulation of AI technology by dividing AI systems into the following groups: prohibited systems with unacceptable risk; high-risk systems; and low- or low-risk systems. Accordingly, regulation will differ according to the classification of AI systems.

Thus, a binding international convention on AI is currently being actively developed in the European Union.

France is a recognized leader in the use of AI in justice among European countries. Thus, in France in 2017, the Case Law Analytics system was created, which allows assessing legal risks and modeling the possible results of litigation. In addition, this system is able to quickly select the most appropriate judicial precedent for the specific circumstances of the case. A similar program is Predictice. However, in the French Law of March 23, 2019 on programming for 2018–2022 and justice reform [33] provides for a ban on fully automated decision-making, i.e. justice can only be administered by a human judge. Thus, these systems can only be used as an auxiliary tool for analyzing court documents, selecting rules of law and suitable judicial precedent.

3.1.5 Russia

Currently, AI technologies are not widely used in the Russian judicial system. The National Strategy for the Development of Artificial Intelligence for the period until 2030, approved by Decree of the President of the Russian Federation dated October 10, 2019 No. 490 “On the development of artificial intelligence in the Russian Federation,” provides for the concept of AI, principles for the development and use of AI technologies, compliance with which is mandatory. The Strategy stipulates that the main task of using AI is the automation of routine (repetitive) production operations, including operations carried out in the administration of justice.

Thus, in order to implement the provisions of this Strategy, a super service “Online Justice” [23] is being developed, which provides for remote submission of procedural documents to the court in electronic form, obtaining information about the progress of the case, participation in a court hearing using web conference technology, receiving electronic copies of court documents signed with an electronic signature court. The opportunity to participate in a court hearing using web conference technology will be ensured by the introduction into judicial activities of technology for biometric authentication of a participant in a trial by face and voice. In addition, this service also involves the automated creation of draft judicial acts based on analysis of the text of the procedural document and case materials. Unlike many foreign services, this system will not automatically make decisions on its own; it is assumed that the AI will only prepare a template for a judicial act, into which the judge can make appropriate changes [19]. Also, this system can be useful for decoding audio protocols. Thus, this service will not replace the judge, but will significantly reduce his workload.

The idea of using AI in the selection procedures for future judges is also being discussed in the judicial community [24]. For example, neural networks could make up a preliminary characteristic of a candidate, based on the results of an assessment of which the competent structures made a decision on appointment.

It should be noted that AI technologies are already being used in Russian justice. Thus, from September 1, 2019, automated distribution of cases was introduced in Russia (Article 18 of the Arbitration Procedure Code of the Russian Federation, Article 14 of the Code of Civil Procedure of the Russian Federation, Article 28 of the Code of Arbitration Procedures of the Russian Federation, Article 30 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation). The system operates both in arbitration courts and in courts of general jurisdiction and is designed to ensure fair distribution of the workload between judges and to exclude the influence of interested parties on this process. The program contains two domains. One contains information about judges—their specialization and pending cases. The second domain contains information on each incoming case in order to assess its complexity.

Based on the results of an analysis of foreign and Russian experience in using AI in justice, it is proposed to distinguish the following forms of work of judicial AI:

-

Cloud service (Hangzhou Internet Court Litigation Platform, China Judgments Online, DCS, Online Justice);

-

Computer program (Case Law Analytics, Predictice);

-

Chat bot (WeChat, ROSS);

-

Machine learning (PSA, COMPAS, Ravel Law, Harm Assessment Risk Tool, PredPol).

In our opinion, the most promising form of judicial AI is machine learning. Thus, machine learning technology makes it possible to make predictions based on the results of the analysis of both procedural documents contained in the case materials and judicial acts issued in similar or similar cases. Based on the analysis of this data set (“training data”), statistical comparisons are established between cases and corresponding court decisions. The more data the algorithm processes, the more accurate its forecasts for new cases will be. Thus, these systems “learn” (even if only from the point of view of increasing statistical accuracy) to reproduce the decisions that judges would make based on similar ones. Unlike digital data and document sharing technologies already in use, this “predictive justice” technology (as it is often incorrectly called) is designed to influence judicial decisions.

Technology, whether it be filing systems, simple online forms or more complex programs using AI, should only be used in litigation if there are proper controls in place.

The control problem is even more acute when it comes to AI systems based on machine learning. In this case, forecasts are based on algorithms that change over time. In machine learning, algorithms “learn” (change) based on their own experiences. When algorithms change, we no longer know how they work or why they behave a certain way. How can we ensure their accountability if we do not have effective control mechanisms? The question remains open. Until technical and institutional solutions are found, the precautionary principle should be followed.

However, it is premature to draw any conclusions about the results of AI in justice at this time, as AI is currently being used mostly on an experimental basis.

3.2 Areas of Use of AI in Justice

3.2.1 Language of Proceedings

As is know, legal proceedings and paperwork in courts are conducted in the state language of a particular state. If necessary, persons participating in the case are given the opportunity to speak in court in their native language, or a freely chosen language of communication, and use the services of an interpreter.

The prospects for using AI in this area are:

-

1)

AI will allow participants in the process to submit documents to the court or speak during court hearings in any language (multilingualism of legal proceedings) thanks to existing speech recognition programs and translating it into text (https://speechpad.ru/, https://dictation.io/, https://realspeaker.net/, https://www.nuance.com/dragon.html and others);

-

2)

AI can also recognize the emotional and psychological components of a speaker’s speech in court [17, 57]. We are talking about speech polygraphs (a technological means of psychophysiological research for assessing the reliability of reported information—a lie detector), allowing a human judge to assess the integrity, reasonableness, awareness or presence of abuse of rights in the behavior of participants in public relations. A similar system has already been developed in the USA and detects perjury from video recordings with an accuracy of 92% of cases based on changes in facial expressions, tone of voice and other parameters (The Dare AI system);

-

3)

Intellectual processing of the speech language and texts of documents presented by the participants in the process will significantly reduce the time required for translating this information into the official language of legal proceedings of the state, and will also reduce the legal costs of the parties, since it will eliminate the need to involve a translator in the case [20]. For example, in the Russian Federation, a resident of the Skolkovo Foundation, the Biorg company, has developed a system that allows recognizing documents and objects, including drawings and handwritten texts in different languages.

3.2.2 Digital Protocol

With the development of electronic justice in court hearings, along with a paper protocol written by hand or using technical means (typewriter, computer and others), an audio protocol is kept in digital format (audio recording).

In the Russian arbitration process, audio recording is recognized as the main means of recording information about the course of a court hearing, as well as a means of ensuring the openness of court proceedings; the material medium of the audio recording is attached to the protocol (clause 16 of the resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation dated 02/17/2011 No. 12 “On some issues of application of the Arbitration Procedural Code of the Russian Federation as amended by the Federal Law dated 07/27/2010 No. 228-FZ “On Amendments to the Arbitration Procedural Code” Russian Federation""). The protocol of the court hearing is an additional means of recording the completed procedural action (Part 2 of Article 155 of the Arbitration Procedure Code of the Russian Federation).

The development of telecommunication technologies and machine intelligence make it possible to record court hearings exclusively in electronic form—in the form of a “digital record” of a court session, without duplicating them on paper.

Thus, audio recording, enabled automatically by artificial intelligence, will optimize the court’s time in recording protocol definitions (digital definitions) and even provide consistent shorthand recording of the court hearing [54, 55]. However, the above does not exclude printing the audio protocol on paper if necessary.

3.2.3 Formation of the Court Composition and Determination of the Category of Cases

In Russia, the composition of the court for consideration of each case, including with the participation of arbitration assessors, is formed taking into account the workload and specialization of judges through the use of an automated information system (Article 18 of the Arbitration Procedure Code of the Russian Federation, Article 14 of the Code of Civil Procedure of the Russian Federation, Article 28 of the CAS of the Russian Federation, Art. 30 Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation).

At present, the automatic formation of the court composition is already in effect, excluding the influence on its formation by persons interested in the outcome of the trial. In this direction, AI can be used not only for the purpose of automated formation of the court composition, but also to determine the category of cases and distribute cases among judicial panels, taking into account the specialization of judges. There are disputes with “borderline” specialization, for example, challenging the decision of the tax authority in a corporate dispute (corporate composition of a civil board) or a tax dispute (tax composition of an administrative board), and AI could quickly limit the claims (statements) filed in court.

3.2.4 Digital Writs of Execution

It seems that the traditional idea of executive documents, in particular, in the form of writs of execution, will be revised in the near future.

For example, in Russia, a significant step towards optimizing the activities of Russian arbitration courts was the establishment of the provision that the issuance of writs of execution is carried out at the request of the claimant (Part 3 of Article 319 of the Arbitration Procedure Code of the Russian Federation, Part 1 Article 428 Code of Civil Procedure of the Russian Federation). These changes were due to the fact that writs of execution issued by the court to collectors often remained unclaimed by the Russian post office or were returned back to the court due to the invalid address of the location of the collector, and often the writ of execution simply lost its relevance, for example, in the event of bankruptcy of the debtor.

The use of AI connected to court information portals (for example, File of Arbitration Cases) would make it possible to automatically determine the need for the issuance of a writ of execution, process requests from claimants (creditors) to issue a writ and/or send it for execution to the Federal Bailiff Service of Russia or to the bank.

3.2.5 Research and Assessment of Evidence, Establishment of Legally Significant Circumstances

One of the most important principles of legal proceedings is the principle of immediacy, according to which the examination and assessment of evidence is carried out directly by the court. This raises the question: does the use of AI violate the principle of immediacy?

To answer this question, it is necessary to determine the functionality of AI as part of the research and evaluation of evidence. AI, as part of the research and evaluation of evidence, can:

-

1)

Carry out analytics that do not contain direct conclusions on issues included in the subject of evidence in a particular case (for example, check the presence in the case materials of documents referred to by the applicant, as well as analyze judicial practice referred to by the applicant in support of claims, with for the purpose of identifying judicial acts that were canceled by a higher authority, etc.). In the present case, AI technical assistance does not replace personal research and assessment by the court of the evidence presented in the case file, but only simplifies the examination of evidence by the court and the parties to the dispute, and therefore the principle of immediacy is not violated;

-

2)

Evaluate the evidence and, on its basis, independently form conclusions about the circumstances relevant to the case. Unlike the first case, where the court is involved in the examination and evaluation of evidence, the court will rely on the conclusions of the AI, regardless of whether they are binding or not. Thus, the direct examination of evidence by the court in this case is excluded. However, when evaluating and forming AI conclusions and their subsequent approval by a judge, the following risks may arise. Thus, the judge will depend on previously known predictions about the outcome of the process, which are based on the conclusions of the AI, and due to the heavy workload, he will prefer to agree with the conclusion of the AI instead of justifying his conclusions and explaining the reason for disagreeing with the AI [36]. In order to prevent the occurrence of such risks, it is necessary to establish conditions that do not allow automatic approval of AI decisions by a judge.

Is the use of AI in the research and evaluation of evidence consistent with the principles of equality of arms and adversarial law? It seems that the principle of equality in this case will be respected if each party is guaranteed the opportunity to present their arguments and evidence, which will be assessed by AI [13]. For example, a violation of this principle would be if the AI checked only in statements of claim references to legal norms and judicial practice for their relevance, while the response to the statement would not be the subject of such a check.

In addition, a guarantee of equality of the parties will be the disclosure of the results of the work of the AI and the provision of each person participating in the case with the opportunity to raise their objections to the conclusions of the AI (by analogy with what is currently provided for comments on the minutes of the court hearing). The establishment of such provisions will also have a positive impact on ensuring the principle of competition between the parties, as well as the transparency of the work of AI. In order to ensure compliance with the adversarial principle of the parties, it is necessary to provide that the subject of research and evaluation of the AI are all documents received in the case materials, both on paper and in electronic form. Otherwise, the principle of competition will be violated.

Thus, the introduction of AI into the process of research and evaluation of evidence will not lead to a violation of the principles of immediacy, equality of arms and competition when ensuring and complying with certain conditions.

Many issues in practice are resolved by the court ordering complex economic, accounting and valuation examinations (for example, determining the marketability of a transaction, calculating the actual value of a share in a unilateral transaction on the withdrawal of a participant from the company, etc.). At the same time, it is enough to provide AI with online access (open a telecommunications channel) to electronic interaction systems, in particular, to the service of the Federal Tax Service of Russia “Transparent Business”, Rosstat—“Accounting Reports of Enterprises”, Rosreestr—“Unified State Register of Real Estate” and other information data, there is no need to order a forensic examination.

We believe that only in exceptional cases will the court order a forensic examination. The reason for this, in particular, may be cases when public information used by AI was based on unreliable information or forged documents, as well as in cases of technical errors in documents (information) or in other controversial situations.

The issue of limitation of actions is essential for the parties to the dispute, since the legal prospects of the case in court depend on this. Missing the limitation period and the absence of valid reasons for restoring this period for the plaintiff—an individual, is a sufficient basis for refusing the claim only on these grounds, without examining other circumstances of the case [43]. Considering that when the court determines the limitation period, the court quite often analyzes information contained in open sources (for example, the Corporate Information Disclosure Center (Interfax), Unified State Register of Legal Entities, Unified State Register of Legal Entities), the use of AI in this matter will be very useful. However, this does not deprive the parties of presenting evidence to refute the conclusions of AI about the running of the limitation period.

3.2.6 Reconciliation of the Parties and Settlement Agreement

As a special case of the use of AI, it seems possible to determine the path to peaceful resolution of the conflict. It is known, by virtue of the norms of Ch. 15 of the Arbitration Procedure Code of the Russian Federation, courts assist the parties in resolving a dispute based on the principles of voluntariness, equality, confidentiality and cooperation. Conciliation procedures are recognized as: negotiations, mediation, including mediation (with the participation of a mediator) [16], judicial conciliation (with the involvement of a judicial conciliator) [42], or other conciliation procedures established by law (Article 138.2 of the Arbitration Procedure Code of the Russian Federation). A settlement agreement is a separate type of peaceful settlement of a conflict.

For a peaceful settlement of a dispute, it is important to understand that it is based on a compromise of the will of the parties, the reasonableness of the conditions and the reality of the fulfillment of the obligations assumed by the parties. Being a civil transaction approved by the court, its provisions must also be verified for possible violation of the rights of third parties (potential negative consequences). In order to assess the prospects for reconciliation of the parties, based on the specific circumstances of the case, the conclusion of a settlement agreement, the reality of its implementation, analysis and prevention of possible negative consequences, AI can be used.

3.2.7 Case Review by AI

One of the most important and interesting questions of modern justice is the question: can a human judge be replaced by a robot judge? [53]. There are several points of view on this issue in the scientific literature. Thus, according to one of them, replacing a judge with an artificial one is premature, and most likely impossible, since the meaning of legislation can only be revealed by a person with a high level of legal culture and ethics [50]. The next argument in favor of the impossibility of replacing a judge with AI is that law enforcement includes not only a formalized part (literal interpretation of the rules of law), but also judicial discretion, which presupposes freedom of choice within the framework of the rules of law. If the rules of law in force in a state can be algorithmized, then judicial discretion, formed through legal consciousness, ideology and principles, cannot be translated into computer code [12].

In addition, there is an opinion that AI is limited. For example, AI does not cope well with abstractions and understanding meaning, which is why it is not able to fully replace human intelligence [35]. In this regard, given that AI can apply law based on certain factors, it is impossible to consider AI as a potential complete replacement for a judge. Under these circumstances, AI should only be considered as a tool used by the court to improve the efficiency of justice. Indeed, AI can significantly reduce the workload of judges when performing routine and similar tasks, for example, accepting statements of claim, issuing writs of execution, preparing court orders, etc.

Nevertheless, a number of scientists have a rather positive attitude towards the introduction of AI in justice. So, in their opinion, although it will not replace a judge, it will become an additional tool for the administration of justice, which will reduce the time it takes to consider cases [4]. A similar position is expressed in his works by the judge of the Arbitration Court of the Moscow District P.M. Morhat, who believes that the introduction of AI in Russian justice is possible only as a “companion judge.” [37]. For example, AI can assist a judge in assessing and analyzing evidence, as well as in judicial practice, in checking the correctness of evidence presented in case materials, and in drawing up draft judicial acts. However, in this case, making a final decision on the case will be within the competence of the judge, who, taking into account the conclusion of AI, will issue one or another judicial act. This approach to the use of AI in justice will allow maintaining a balance of human rights and freedoms through the implementation of the principle of user control enshrined in the European Ethical Charter on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Judicial Systems.

In our opinion, it seems justified to transfer cases considered by order and simplified proceedings to AI for consideration. The feasibility of transferring these categories of cases to AI for consideration is as follows: firstly, a significant reduction in the judge’s workload, since these categories of cases make up a significant part of the cases considered by Russian arbitration courts; secondly, a court hearing with the participation of interested parties is not required; thirdly, the issuance of a court order and summary judgment is based on the analysis of only written evidence, which can be assessed by AI. Some scholars believe that in such categories of cases, the function of the court is essentially reduced to confirmation and certification, and that is why it is possible to automate the decision-making process [14]. However, if such cases are referred to the AI at the legislative level, it is necessary to provide for the opportunity for persons participating in the case to object to the consideration of such disputes by the AI and the transition to consideration according to the general rules of legal proceedings.

Thus, based on the results of the analysis, the following groups of areas of use of AI in justice can be distinguished: organizational sphere of activity of courts (registration of cases, formation of the court composition, recording, etc.); assessment of evidence and establishment of legally significant circumstances; consideration of the case by AI.

4 Results

Based on the results of the study, the authors formulated the following conclusions and proposals.

-

1)

The use of judicial AI is possible only if guarantees are provided for human rights and interests. Thus, at the stage of AI development, it is necessary to comply with ethical principles and ensure the equality of citizens before the law. In addition, persons participating in the case should be given the opportunity to object to the use of judicial AI, and the right to appeal a decision made by judicial AI should be guaranteed.

-

2)

The authors identified the following areas of use of AI in justice:

-

Organizational sphere of activity of courts (registration of cases, formation of the court composition, recording, etc.);

-

Assessment of evidence and establishment of legally significant circumstances;

-

Consideration of the case by artificial intelligence.

-

-

3)

Based on the understanding of AI as a simulated (artificially reproduced) intellectual activity of human thinking, the following stages of its implementation in the system of domestic courts are proposed [25]:

-

Short-term perspective: the introduction of AI as an assistant to a human judge on certain issues of office work and when considering a case on the merits (for example, keeping minutes of a court hearing, forming a court panel, preparing writs of execution) [3, 8];

-

Medium-term perspective (5–10 years): will allow us to consider AI as a judge-companion of a human judge, including on the issue of assessing a number of evidence:

-

Determination of the category and legal properties of the transaction (form, date, authenticity of the electronic signature);

-

Checking the calculation of claims (amount of contractual penalty, actual damage or lost profits);

-

Determination of missing the statute of limitations and the deadline for going to court;

-

Proposal for reconciliation of the parties (options of settlement agreements or prospects for using mediation procedures).

-

-

Long-term perspective: possible replacement of a human judge with AI to perform certain functions in the administration of justice, for example, when making decisions on certain categories of disputes. In our opinion, autonomous decision making is possible under the following conditions:

-

Lack of evaluative norms regulating controversial legal relations;

-

The parties' claims are based on digitized written evidence or evidence obtained from automated information systems;

-

Rights, duties and responsibilities are clearly defined in legislation.

-

-

-

4)

The authors concluded that the use of judicial AI will not lead to a violation of the principle of immediacy, adversary and equality of the parties, subject to certain conditions.

-

5)

The authors identified the following forms of work of judicial AI:

-

Cloud service (Hangzhou Internet Court Litigation Platform, China Judgments Online, DCS, Online Justice);

-

Computer program (Case Law Analytics, Predictice);

-

Chat bot (WeChat, ROSS);

-

Machine learning (PSA, COMPAS, Ravel Law, Harm Assessment Risk Tool, PredPol).

At this time, it is premature to draw any conclusions about the results of using AI in justice, since AI is currently being used primarily on an experimental basis.

-

-

6)

The authors concluded that the use of AI ensures the development of technological jurisprudence in terms of the objective establishment of legal facts, and the public disclosure of digital algorithms for the work of judicial AI will give greater digital transparency to legal proceedings and ensure transparency of the work of machine intelligence. However, technology, whether it be filing systems, simple online forms or more complex programs using AI, should only be used in litigation if there are proper controls in place.

-

7)

The authors noted that the work of AI at the current stage is possible exclusively in conjunction with a human judge, similar to a co-robot (collaborative robot controlled by a person). We are talking about the combined work of AI in tandem with a human judge or under control in the field of legal-machine processing and evaluation of evidence as information about the facts on which the parties justify their position in court.

5 Conclusions

Electronic justice at the present stage of development of information technology has moved to a qualitatively new level. Traditional document flow in paper form is being actively replaced by documents in digital format.

The proposed forecast for the stages of implementation of judicial-AI is primarily based on the level of development of information technology. At present, AI has not yet been created that is close to the cognitive abilities of the human brain and its billions of neurons. It is necessary to use AI in matters that require processing a large amount of information and documents in electronic form. So, for example, if AI transfers certain routine functions of the court records department and the judge himself, the judge will have additional time for a more detailed study of the case materials and analytical work. AI will provide procedural savings and reduce the time for considering disputes on the merits through the speed and accuracy of calculations.

In conclusion, it can be argued that the technology of forensic AI should be open, reliable and transparent for all citizens, business entities and society as a whole. This approach will ensure public confidence in the court and the modern information technologies introduced into its work: AI and cloud computing. The development of digital technologies in the era of the information society and big data has proven the prospects for introducing AI in court [26].

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AI :

-

Artificial intelligence

- Judicial AI :

-

Judicial artificial intelligence

References

Andreev VK, Laptev VA, Chucha SYu. Artificial intelligence in the electronic justice system when considering corporate disputes. Bulletin of St. Petersburg University. Right. 2020. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu14.2020.102.

Angwin J, Larson J, Mattu S, Kircher L. Machine bias. In: Ethics of data and analytics. Pro-Publica; 2016. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003278290.

Astapkovich V. Artificial intelligence was involved in making court decisions in Russia. RIA NEWS. 2021. https://ria.ru/20210525/intellekt-1733789200.html. Accessed 7 Sept 2023.

Badenes-Olmedo C, Redondo-Garcia JL, Corcho O. Legal document retrieval across languages: topic hierarchies based on Synsets. Horizon. 2020. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1911.12637.

Biryukov PN. Artificial intelligence and “predictive justice”: foreign experience. Lex Russica. 2019. https://doi.org/10.17803/1729-5920.2019.156.11.079-087.

Brader C. AI technology and the justice system: lords committee report. House of lords library. 2022. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/ai-technology-and-the-justice-system-lords-committee-report/#:%7E:text=The%20report%20was%20published%20on,in%20the%20criminal%20justice%20system. Accessed 5 Sept 2023.

Burgers M. UK police are using AI to inform custodial decisions – but it could be discriminating against the poor. Wired. 2018. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/police-ai-uk-durham-hart-checkpoint-algorithm-edit. Accessed 12 Sept 2023.

Burnov V. Artificial intelligence helps collect debts in the Belgorod region – Momotov. RASPI. 2021. http://rapsinews.ru/judicial_news/20210525/307072815.html. Accessed 7 Sept 2023.

Chen J. Issues and return of “Cloud Trial” in criminal cases. Shanghai Law Society. 2020. http://www.shanxilawsociety.org.cn/newsshow/6382.html. Accessed 1 Sept 2023.

Chen Y. The supreme court issued the 25th five-year reform outline. People’s Court News. 2005. http://www.china-judge.com/ReadNews.asp?NewsID=3280&BigClassName=%CB%BE%B7%A8%B8%C4%B8%EF&BigClassID=17&SmallClassID=25&SmallClassName=%CB%BE%B7%A8%B8%C4%B8%EF&SpecialID=0. Accessed 1 Sept 2023.

Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of December 27, 2012 No. 1406 “On the federal target program “Development of the judicial system of Russia for 2013–2024”.

Digital economy: current directions of legal regulation: scientific and practical guide / Dyakonova MO, Efremov AA, Zaitsev OA, others; edited by Kucherova II, Sinitsyn SA. Moscow: IZiSP, NORMA; 2022.

Drozd DO. How can the Use of Artificial Intelligence affect equality of arms and competition? Arbitr Civ Process. 2023. https://doi.org/10.18572/1812-383X-2023-6-9-13/.

Dyakonova MO. Digitalization of the judicial process: protection of rights and electronic technologies. Judge. 2020;11:24–21.

Ethical charter on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in judicial systems and their environment. Adopted at the 31st plenary meeting of the CEPEJ (Strasbourg, 3–4 December 2018). https://rm.coe.int/ethical-charter-en-for-publication-4-december-2018/16808f699c. Accessed 10 Sept 2023.

Federal Law of July 27, 2010 No. 193-FZ “On an alternative procedure for resolving disputes with the participation of a mediator (mediation procedure)”.

Fersini E, Messina E, Archetti F, Cislaghi M. Semantics and machine learning: a new generation of court management systems. Commun Comput Inf Sci. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29764-9_26.

Founder N-W, Herik J, Salem A-B. Digitally produced judgements in modern court proceedings. Int J Digit Soc. 2015;6(4):1112–1101.

Gorovtsova M. Chairman of the council of judges of the Russian Federation: artificial intelligence will participate in the preparation of court orders. Garant.ru. 2021. http://www.garant.ru/news/1464883. Accessed 7 Sept 2023.

Guodong Du, Meng Yu. Big data, AI and China's justice: here's what's happening. China justice observer. 2019. https://www.chinajusticeobserver.com/a/big-data-ai-and-chinas-justice-heres-whats-happening. Accessed 1 Sept 2023.

Ji W. The change of judicial power in China in the era of artificial intelligence. Asian J Law Soc. 2020;7:530–515.

Kolokolov NA. Artificial intelligence in justice - the future is inevitable. Bull Moscow Univ Ministry Internal Affairs Russia. 2021;3:212–201.

Kulikov V. Vyacheslav Lebedev spoke about the creation of the Justice Online superservice. Reviews of media materials. Supreme Court of the Russian Federation. 2021. http://www.vsrf.ru/press_center/mass_media/30377/. Accessed 10 Sept 2023.

Kulikov V. Vyacheslav Lebedev: more than 7 million electronic documents have been submitted to the courts of the Russian Federation. Reviews of media materials. Supreme Court of the Russian Federation. 2023. https://www.supcourt.ru/press_center/mass_media/32569/. Accessed 10 Sept 2023.

Laptev VA. Artificial intelligence in court (Judicial AI): legal foundations and prospects for its work. Russian Justice. 2021;7:13–10.

Laptev VA. Artificial intelligence in court: how it will work. Pravo.ru. 2021. https://pravo.ru/opinion/232129/. Accessed 1 Sept 2023.

Laptev VA. The concept of artificial intelligence and legal responsibility for its work. Law J High School Econ. 2019. https://doi.org/10.17323/2072-8166.2019.2.79.102.

Laptev VA, Chucha SYu, Feyzrakhmanova DR. Digital transformation of modern corporation management tools: the current state and development paths. Law Enforc Rev. 2022. https://doi.org/10.52468/2542-1514.2022.6(1).229-244.

Laptev VA, Ershova IV, Feyzrakhmanova DR. Medical applications of artificial intelligence (legal aspects and future prospects). Laws. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11010003.

Laptev VA, Feyzrakhmanova DR. Digitalization of institutions of corporate law: current trends and future prospects. Laws. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws10040093.

Laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain union legislative acts. EUR-Lex. 2021. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1623335154975&uri=CELEX%3A52021PC0206. Accessed 10 Sept 2023.

Lee K-F. Artificial intelligence superpowers. China, Silicon Valley and the new world order. Kai-Fu Lee; 2019.

Loi n° 2019–222 du 23 mars 2019 de programmation 2018–2022 et de réforme pour la justice. Journal official du. 2019. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/dossierlegislatif/JORFDOLE000036830320/. Accessed 3 Sept 2023.

Luo Q, Yang G. Promoting the QQ tribunal. People’s court news. 2015. http://gz.people.com.cn/n/2015/0209/c194827-23840896.html. Accessed 1 Sept 2023.

Makutchev AV. Modern possibilities and limits of introducing artificial intelligence into the justice system. Curr Probl Russian Law. 2022. https://doi.org/10.17803/1994-1471.2022.141.8.047-058.

Momotov VV. The space of law and the power of technology in the mirror of judicial practice: a modern view. J Russian Law. 2023. https://www.doi.org/10.12737/jrp.2023.021.

Morhat PM. Application of artificial intelligence in litigation. Bull Civ Procedure. 2019. https://doi.org/10.24031/2226-0781-2019-9-3-61-85.

Neznamov AV. Principles of using artificial intelligence technologies in justice: a European approach. Educ Law. 2019;5:227–222.

Order of the Government of the Russian Federation of February 13, 2019 No. 207-“On approval of the Spatial Development Strategy of the Russian Federation for the period until 2025”.

Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Trial of Cases by Internet Courts. Court Provisions. 2018. http://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-116981.html. Accessed 12 Sept 2023.

Realing AD. Courts and artificial intelligence. Int J Court Adm. 2020. https://doi.org/10.36745/ijca.343.

Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of October 31, 2019 No. 41 “On approval of the Rules for conducting judicial conciliation”.

Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of September 29, 2015 No. 43 “On some issues related to the application of the provisions of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation on the limitation period”.

Rodikova VA. Artificial intelligence vs judicial discretion: trust cannot be verified. Prospects and risks of automation of judicial practice. Bull Arbitr Pract. 2023;3:50–37.

Rubim P, Fortes B. Paths to digital justice: judicial robots, algorithmic decision-making, and due process. Asian J Law Soc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1017/als.2020.12.

Schmitz AJ. Expanding access to remedies through E-court initiatives. Buffalo Law Review. 2019; 67. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol67/iss1/3.

Shi C, Sourdin T, Li B. The smart court–a new pathway to justice in China? Int J Court Adm. 2021. https://doi.org/10.36745/ijca.367.

Surden H. Artificial intelligence and law: an overview. Georgia State Univ Law Rev. 2019; 35(4):1337–1304. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3411869.

Susskind R. Online courts and the future of justice. Oxford: University Press; 2019; p. 368.

Sycheva OA. Common sense in judicial proof. Russian Judge. 2019;8:20–15.

Talapina EV. Data processing using artificial intelligence and the risks of discrimination. Law J High School Econ. 2022;15(1):27–4.

The Digital Europe Programme for the Period 2021–2027. EUR-Lex. 2018. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52018PC0434. Accessed 12 Sept 2023.

Transformation of the paradigm of law in the civilizational development of mankind: reports of members of the Russian Academy of Sciences / Ed. ed. member-corr. RAS A.N. Savenkova. M.: Institute of State and Law of the Russian Academy of Sciences; 2019.

Wang N. “Black Box Justice”: robot judges and ai-based judgment processes in China's court system. International Symposium on Technology and Society. Proceedings. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISTAS50296.2020.9462216.

Wang Z. China’s E-justice Revolution. 105 Judicature. 2021; 36:13–1. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3629963.

White paper on the application of internet technology in judicial practice. Beijing Internet Court Anniversary Series. 2019. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/specials/WhitePaperontheApplicationofInternetTechnologyinJudicialPractice.pdf. Accessed 5 Sept 2023.

Wu Z, Singh B, Davis L, Subrahmanian V. Deception detection in videos. AAAI conference on artificial intelligence. 2017. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1712.04415.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.L. and D.R.F.; methodology, D.R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.L. and D.R.F.; writing—review and editing, V.A.L. and D.R.F.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Laptev, V.A., Feyzrakhmanova, D.R. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Justice: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Hum-Cent Intell Syst (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44230-024-00074-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44230-024-00074-2