Abstract

Health disparities in multiple myeloma (MM) disproportionately affect minorities. Characterization of health disparities encountered by Hispanic Americans with MM is necessary to identify gaps and inform future strategies to eliminate them. We performed a systematic review of publications that described health disparities relevant to Hispanic Americans with MM through December 2021. We included all original studies which compared incidence, treatment, and/or outcomes of Hispanic Americans with other ethnic groups. Eight hundred and sixty-eight articles were identified of which 22 original study articles were included in our systematic review. The number of publications varied over time with the highest number of studies (32%) published in 2021. Most of the published studies (59%) reported worse outcomes for Hispanic Americans with MM compared to other ethnic groups. There is growing evidence that Hispanic Americans with MM are facing a multitude of disparities that require immediate attention and solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is characterized by neoplastic proliferation of plasma cells producing a monoclonal immunoglobulin that may result in end-organ damage. MM occurs in all races and all geographic locations. The incidence varies by ethnicity; the incidence in Black populations is two to three times that of non-Hispanic Whites in studies from the United States and United Kingdom [1].

The United States Census Bureau uses Hispanic to refer to a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race and states that Hispanics or Latinos can be of any race, any ancestry, or any ethnicity [2, 3]. Hispanics are the largest and fastest-growing minority group in the U.S., and they currently make up approximately 15% of the U.S. population [4]. Hispanic Americans continue to face multiple health disparities related to MM. MM-related in-hospital mortality was significantly higher in Hispanic Americans when compared to non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Blacks. Disparities in MM care for Hispanics in the U.S. continue to persist despite recent advancements in MM therapy [5]. This can be related to limited access to care and lower utilization of effective MM therapies. There are limited data on health disparities experienced by Hispanic Americans. We aimed to review the literature for studies which reported on health disparities in Hispanic American patients with MM.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature Search and Selection

We searched EMBASE, MEDLINE/PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, and Web of Science for English-language literature through December 2021 using the terms “multiple myeloma”, “plasmacytoma”, “Hispanic Americans”, “Hispanic”, “Spanish Americans”, “Latino”, “Latina”, “Spanish speaking”, “health disparities”, “healthcare disparities”, “disparities”. All searches were conducted during December 2021. We used methodology from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement to guide our search, analyses, and reporting [6]. We used MESH (Medical Subject Headings) terms as they are universally used in indexing journal articles and books in the life sciences. The combinations of the terms used are listed in Table 1.

2.2 Study Abstraction and Analysis

Two authors (A.A.G., S.A.H) with clinical backgrounds in clinical research, medical oncology, hematology, and internal medicine participated in study selection. Research studies were accepted if they included Hispanic Americans as part of the studied population. Review articles, editorials, studies that solely described protocols, non-research letters, abstracts of congresses, and books were excluded. Also excluded were health disparities studies which did not report specific results on Hispanic Americans and/or included their results under ‘others’.

The studies’ abstracts were reviewed for eligibility, and full papers were reviewed if eligibility was not clear from the abstract review alone. Each study was categorized under a specific domain that included the major study aim and/or finding. Categories included incidence, socioeconomic status, treatment, clinical trial participation and mortality.

3 Results

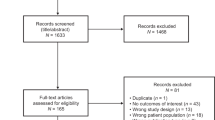

Our wider broad search retrieved a total of 868 records, of which 212 reports were related to the same patients. After in-depth screening, 595 reports were excluded for not fulfilling the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of the remaining 61 records, 39 reports were also excluded after full text review for not meeting the eligibility criteria. A total of 22 studies focused on Hispanic Americans with MM were included [5, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. We categorized the articles based on topic, year of publication and author. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics and conclusions of the articles according to the domain.

The number of publications varied over time with the highest number of studies (32%) published in 2021. The articles were published in 16 different journals with 179 different contributing authors. Fifty-nine percent of the included articles reported worse outcomes for Hispanic Americans when compared with other ethnic groups.

The incidence of MM in Hispanics is higher and with a median age at presentation 5 years younger than in non-Hispanic Whites [7, 10]. Some prior studies suggested no difference in incidence of MM in Hispanics when compared to non-Hispanic Whites [9]. There was no difference in adverse risk cytogenetics between Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Blacks [7]. Socioeconomic status (SES) reflected by residence zip code and poverty level was shown to be different among different ethnic groups with higher proportion of Hispanic Americans living in lower SES zip codes and zip codes with low education levels [11,12,13]. Hispanic Americans were found to receive less MM maintenance therapy and less supportive therapies such as bisphosphonates [14, 15].

A longer time from MM diagnosis to novel therapy initiation was more prevalent in Hispanic Americans when compared to non-Hispanic Whites [16]. Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) use in Hispanic Americans is lower than non-Hispanic Whites and, despite the incremental use of ASCT from 2008 to 2014, Hispanic Americans had the lowest rates of ASCT when compared to all other ethnic groups [16, 18, 19, 21].

Enrollment in MM clinical trials was lower in Hispanic Americans [17, 22, 23]. The rate of in-hospital mortality was higher in Hispanic Americans when compared to other ethnic groups [5]. Despite the earlier age of diagnosis, Hispanic Americans were found to be at higher risk of death, which may be related to lower SES [25]. Improvement in MM survival, in this treatment landscape era of improved therapy options, was least pronounced in Hispanic Americans [26].

4 Discussion

We found that Hispanic Americans had a higher incidence of MM compared to non-Hispanic whites. Our review found that Hispanic Americans with MM tend to live in areas with low SES and education levels. This is in line with prior data suggesting that Hispanic Americans are more likely to live in poverty than non-Hispanic Whites. Generally, lower SES among people of color in the U.S. stems from long-term structural racism or racism that is reinforced by discriminatory laws, economic policies, and societal and cultural norms [27].

Many Hispanic patients face financial, structural, and personal barriers to health care. In fact, Hispanic people continue to be the least likely to have health insurance of any major ethnic group [27,28,29]. When they have equal access to therapy, Hispanic Americans have survival similar to non-Hispanic Whites and African Americans [7]. Hispanic patients might not experience similar benefits from the introduction of novel therapies and even standard treatment, as their outcomes are worse than non-Hispanic Whites and, in some cases, worse than the rest of the other ethnic groups, at least in part because they received novel therapies later than non-Hispanic Whites [16].

Gender-dependent differences may influence the primary genetic events of MM. Women have a poor prognosis with higher prevalence of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene translocations, which was found to be associated with inferior overall survival [30]. However, no obvious differences in significant measures of genomic variation were found in Hispanic Americans when compared to non-Hispanic Whites [31].

Hispanic patients continue to be the smallest proportion of patients on trials utilizing novel therapeutic agents in MM [22]. Cancer is the leading cause of death among Hispanics. However, only 1.3% of eligible Hispanic cancer patients participate in cancer-related clinical trials [32, 33]. Patient education on clinical trials and materials in Spanish can improve their enrollment [34].

Hispanics are the United States' largest and fastest-growing minority group. They currently make up about 15 percent of the U.S. population [4]. However, only 5.8% of active physicians are Hispanic [35]. Moreover, Hispanic doctors made only 3.3% of awardees from the seven major Hematology-Oncology societies [36,37,38]. As a possible solution, it would be of public interest to diversify the medical workforce. Minority patients are more likely to choose a minority physician and are more satisfied with their care when it is provided by a minority physician [39, 40].

Our review shows that the highest number of studies pertaining to disparities in the MM Hispanic American population were published in 2021 (32%). This likely reflects an increased awareness regarding the scope of this problem and a call to action to combat these prevalent disparities. Studies from Latin America suggested a poor progression-free survival (PFS) among patients with relapsed MM and a slower uptake of newer therapies in public clinics [41].

Our study has some limitations. While we conducted a rigorous, scoping review of existing literature, we did not assess the quality of the included studies. We may have missed published literature that was not captured using our search terms and some publications may have been misclassified. Additionally, the included studies may have varied in their definition of “Hispanics”. For example, some specifically looked at Hispanic Whites and Hispanic Blacks. Nevertheless, our study summarizes the current scope of health disparities experienced by Hispanic Americans and highlights areas that require immediate attention.

5 Conclusion

We found a growing body of articles that studied health disparities that affect Hispanic Americans with MM. Most of the articles reported worse clinical outcomes for Hispanic Americans compared to other ethnic groups. There is an urgent need to implement systemic and structural solutions to current barriers precluding equitable access to care for Hispanic patients.

Availability of Data and Material

The data supporting this study's findings are available on request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- MM:

-

Multiple myeloma

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- MESH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- ASCT:

-

Autologous stem cell transplantation

- NH:

-

Non-Hispanic

- NHW:

-

Non-Hispanic white

- NHB:

-

Non-Hispanic black

- API:

-

Asian Pacific Islander

- RSR:

-

Relative survival rate

References

Waxman AJ, Mink PJ, Devesa SS, Anderson WF, Weiss BM, Kristinsson SY, et al. Racial disparities in incidence and outcome in multiple myeloma: a population-based study. Blood. 2010;116(25):5501–6.

“The Hispanic Population: 2010” (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. May 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

Passel JS, Taylor P. “Who’s Hispanic?”. Pew Research Center; 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

Passel JS, Cohn D. U.S. Population Projections: 2005–2050 [Internet]. Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project; 2008 [cited 2022 Jan 7]. Available from https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005-2050/.

Al Hadidi S, Dongarwar D, Salihu HM, Kamble RT, Lulla P, Hill LC, et al. Health disparities experienced by Black and Hispanic Americans with multiple myeloma in the United States: a population-based study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62:3256–63.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev [Internet]. 2015 Jan 1 [cited 2020 Mar 14];4(1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4320440/.

Kaur G, Saldarriaga MM, Shah N, Catamero DD, Yue L, Ashai N, et al. Multiple myeloma in hispanics: incidence, characteristics, survival, results of discovery, and validation using real-world and connect MM registry data. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21(4):e384–97.

Castañeda-Avila MA, Ortiz-Ortiz KJ, Torres-Cintrón CR, Birmann BM, Epstein MM. Trends in cause of death among patients with multiple myeloma in Puerto Rico and the United States SEER population, 1987–2013. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(1):35–43.

Costa LJ, Brill IK, Omel J, Godby K, Kumar SK, Brown EE. Recent trends in multiple myeloma incidence and survival by age, race, and ethnicity in the United States. Blood Adv. 2017;1(4):282–7.

Ailawadhi S, Aldoss IT, Yang D, Razavi P, Cozen W, Sher T, et al. Outcome disparities in multiple myeloma: a SEER-based comparative analysis of ethnic subgroups. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(1):91–8.

Castañeda-Avila MA, Jesdale BM, Beccia A, Bey GS, Epstein MM. Differences in survival among multiple myeloma patients in the United States SEER population by neighborhood socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity. Cancer Causes Control. 2021;32(9):1021–8.

Evans LA, Go R, Warsame R, Nandakumar B, Buadi FK, Dispenzieri A, et al. The impact of socioeconomic risk factors on the survival outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a cross-analysis of a population-based registry and a tertiary care center. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21(7):451-460.e2.

Kamath GR, Renteria AS, Jagannath S, Gallagher EJ, Parekh S, Bickell NA. Where you live can impact your cancer risk: a look at multiple myeloma in New York City. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;48:43-50.e4.

Joshi H, Lin S, Fei K, Renteria AS, Jacobs H, Mazumdar M, et al. Multiple myeloma, race, insurance and treatment. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;73: 101974.

Zhou J, Sweiss K, Nutescu EA, Han J, Patel PR, Ko NY, et al. Racial disparities in intravenous bisphosphonate use among older patients with multiple myeloma enrolled in medicare. JCO Oncol Practice. 2021;17(3):e294-312.

Ailawadhi S, Parikh K, Abouzaid S, Zhou Z, Tang W, Clancy Z, et al. Racial disparities in treatment patterns and outcomes among patients with multiple myeloma: a SEER-Medicare analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(20):2986–94.

Ailawadhi S, Jacobus S, Sexton R, Stewart AK, Dispenzieri A, Hussein MA, et al. Disease and outcome disparities in multiple myeloma: exploring the role of race/ethnicity in the Cooperative Group clinical trials. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8(7):67.

Schriber JR, Hari PN, Ahn KW, Fei M, Costa LJ, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, et al. Hispanics have the lowest stem cell utilization rate for autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple myeloma in the United States: a CIBMTR report. Cancer. 2017;123(16):3141–9.

Ailawadhi S, Frank RD, Advani P, Swaika A, Temkit M, Menghani R, et al. Racial disparity in utilization of therapeutic modalities among multiple myeloma patients: a SEER-medicare analysis. Cancer Med. 2017;6(12):2876–85.

Costa LJ, Huang J-X, Hari PN. Disparities in utilization of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for treatment of multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(4):701–6.

Al-Hamadani M, Hashmi SK, Go RS. Use of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation as initial therapy in multiple myeloma and the impact of socio-geo-demographic factors in the era of novel agents. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(8):825–30.

Jayakrishnan TT, Bakalov V, Chahine Z, Lister J, Wegner RE, Sadashiv S. Disparities in the enrollment to systemic therapy and survival for patients with multiple myeloma. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2021;14(3):218–30.

Duma N, Azam T, Riaz IB, Gonzalez-Velez M, Ailawadhi S, Go R. Representation of minorities and elderly patients in multiple myeloma clinical trials. Oncologist. 2018;23(9):1076–8.

Ailawadhi S, Azzouqa A-G, Hodge D, Cochuyt J, Jani P, Ahmed S, et al. Survival trends in young patients with multiple myeloma: a focus on racial-ethnic minorities. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19(10):619–23.

Costa LJ, Brill IK, Brown EE. Impact of marital status, insurance status, income, and race/ethnicity on the survival of younger patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma in the United States. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3183–90.

Pulte D, Redaniel MT, Brenner H, Jansen L, Jeffreys M. Recent improvement in survival of patients with multiple myeloma: variation by ethnicity. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(5):1083–9.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanic/Latino People 2021–2023. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc 2021 [Internet]. Available from: www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-hispanics-and-latinos/hispanic-latino-2021-2023-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf&chunk=true.

Velasco-Mondragon E, Jimenez A, Palladino-Davis AG, Davis D, Escamilla-Cejudo JA. Hispanic health in the USA: a scoping review of the literature. Public Health Rev. 2016;37:31.

Scheppers E, van Dongen E, Dekker J, Geertzen J, Dekker J. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: a review. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):325–48.

Boyd KD, Ross FM, Chiecchio L, Dagrada G, Konn ZJ, Tapper WJ, et al. Gender disparities in the tumor genetics and clinical outcome of multiple myeloma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(8):1703–7.

Williams L, Blaney P, Boyle EM, Ghamlouch H, Wang Y, Choi J, et al. Hispanic or Latin American ancestry is associated with a similar genomic profile and a trend toward inferior outcomes in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma as compared to non-Hispanic white patients in the multiple myeloma research foundation (MMRF) CoMMpassstudy. Blood. 2021;138(Supplement 1):4117.

Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2720–6.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30.

Rangel ML, Heredia NI, Reininger B, McNeill L, Fernandez ME. Educating hispanics about clinical trials and biobanking. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(6):1112–9.

Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018 [Internet]. AAMC. [cited 2022 Jan 7]. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018.

Anampa-Guzmán A, Brito-Hijar AD, Gutierrez-Narvaez CA, Molina-Ruiz AR, Simo-Mendoza V, González-Woge M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology—sponsored oncology student interest groups in Latin America. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1439–45.

Patel SR, Pierre FS, Velazquez AI, Ananth S, Durani U, Anampa-Guzmán A, et al. The Matilda effect: under-recognition of women in hematology and oncology awards. Oncologist. 2021;26(9):779–86.

ASCO-Sponsored Oncology Student Interest Groups in the World | JCO Global Oncology [Internet]. [cited 2021 Nov 30]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1200/GO.21.00353.

Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–15.

Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(3):296–306.

de MoraesHungria VT, Martínez-Baños DM, Peñafiel CR, Miguel CE, Vela-Ojeda J, Remaggi G, Duarte FB, Cao C, Cugliari MS, Santos T, Machnicki G, Fernandez M, Grings M, Ammann EM, Lin JH, Chen YW, Wong YN, Barreyro P. Multiple myeloma treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in the Latin America Haemato-Oncology (HOLA) observational study, 2008–2016. Br J Haematol. 2020;188(3):383–93.

Ailawadhi S, Frank RD, Sharma M, Menghani R, Temkit M, Paulus S, et al. Trends in multiple myeloma presentation, management, cost of care, and outcomes in the medicare population: a comprehensive look at racial disparities. Cancer. 2018;124(8):1710–21.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere thanks to Mr. Breandan Richard Quinn for his help and assistance in editing and proofreading this article.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: all authors. Administrative support: all authors. Collection and assembly of data: all authors. Data analysis and interpretation: all authors. Manuscript writing: all authors. Final approval of manuscript: all authors. Accountable for all aspects of the work: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest were reported.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

All authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anampa-Guzmán, A., Alam, S.T., Abuali, I. et al. Health Disparities Experienced by Hispanic Americans with Multiple Myeloma: A Systematic Review. Clin Hematol Int 5, 29–37 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44228-022-00026-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44228-022-00026-2