Abstract

Successful entrance into specialty training represents a pivotal stage in the careers of medical officers. Selection for entrance into specialty training programs may encompass criteria including research experience, regional exposure, clinical experience, professional achievements, diversity, equity and inclusion factors, and extracurricular activities. Despite multiple syntheses on the topic, the extent to which these individual criteria predict performance during training and practice remains unclear. The objective of this study are to robustly conclude, through an umbrella review of systematic reviews on the topic, which selection criteria used in the selection process for medical and surgical specialty training applicants best predict clinical performance during and after specialty training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Successful entrance into a medical or surgical specialty training program represents a pivotal stage in the careers of medical students and trainee medical officers, demanding not only exceptional clinical aptitude but also a well-rounded professional portfolio. Specialty training occurs at varying times in a medical officer’s career dependent on their country of practice, but in the US, commences following medial school, starting with internship and continuing with residency posts [1]. The duration of specialty training varies between each respective program, but trainees can expect to complete their program after three to seven years [1]. Following completion of specialty training, trainees ascertain accreditation to practice as attending consultants in their respective field. Amidst a landscape in which the number of medical school graduates outpaces the expansion of postgraduate training positions, specialty training reprensents a highly competitive process [2]. Consequently, candidates are compelled to align their professional endeavours with the established selection criteria, aiming to optimize their prospects of securing a training position [2]. These candidates are defined as the participants within this review.

Globally, the selection criteria for entrance into specialty training programs are multifaceted, encompassing criteria including research experience, regional exposure, clinical experience, professional achievements, diversity, equity and inclusion factors, and extracurricular activities [2, 3]. These criteria, often encapsulated within the curriculum vitae (CV) of applicants, serve as the initial gateway for selection committees to assess the suitability of candidates prior to subjective applicant analysis utilising traditional or virtual interviews, multiple mini interviews (MMI), or situational judgement tests (SJT) [4]. The situational judgement test aims to assess an applicant’s traits and subsequent suitability for the training program by analysing how the applicant responds to complex and professional scenarios [5]. Current selection criteria in the US Specialty Match is based on locally decided objective and subjective criteria that varies between individual training programs across university colleges in different states [6]. Contrarily, Muecke et al. found that in Australia and New Zealand, of the 47 specialty training programs, 14 publish nationwide publicly available selection criteria [2]. A recent scoping review by Zastrow et al. compiled various calls to reform the US selection process due to the increasing competition and inefficiencies within the selection framework [7]. Nonetheless, the effect to which the evidence for selection criteria predicting performance during and after specialty training and the extent to which this is reflected within selection criteria remains unknown.

Current literature underscores the significance of various selection criteria, ranging from clinical competencies and academic achievements to extracurricular involvements, in shaping the professional trajectories of medical and surgical trainees [6, 8]. However, current syntheses on the topic provide unclear conclusions due to factors including a varying range of clinical, methodological and statistical heterogeneity, reduced strength of association between selection criteria and performance prediction, and low number of included synthesised primary articles. As such, the extent to which each of these individual criteria predict long-term success in training and practice remains unclear. By synthesizing and critically appraising the findings of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on this topic, the objective of this study are to provide robust conclusions regarding which selection criteria used in the selection process for medical and surgical specialty training applicants best predict clinical performance during and after specialty training. Accordingly, the present umbrella review builds on the existing literature to provide robust conclusions on performance-predictive selection criteria and pathways forward. The phenomena of interest pertain to the publicised selection criteria that has been obtained following data extraction of included syntheses. The outcomes sought aim to assess which of these selection criteria best predict clinical performance during and post specialty training. Our findings indicating the respective selection criteria and their prediction of performance in three key performance outcomes can be observed in Table 1.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design, search stategy and selection criteria

The development and reporting of this umbrella review were in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for umbrella reviews. Registration with PROSPERO registry (CRD42024513975) was performed prospectively. The databases PUBMED, EMBASE, Cochrane and PsychInfo were searched from inception to 12/02/2024. The search employed, which was based on the objectives of the review, utilised the following terms: (specialty training applicant OR medical training applicant OR surgical training applicant OR trainee medical officer OR trainee OR medical student OR resident medical officer OR junior medical officer OR medical intern OR doctor OR physicians OR specialist) AND (selection criteria OR selection process OR training selection OR personnel selection OR resident selection OR resident selection criteria OR trainee characteristics OR medical intern characteristics OR medical student characteristics) AND (medical field training OR specialty training OR registrar training OR resident training OR medical training OR surgical training OR physician training OR training OR residency OR specialty OR specialty boards OR specialisation OR specialization OR preceptorship OR residency and internship) AND (academic success OR success OR trainee success OR resident success OR registrar success OR doctor success OR performance OR trainee performance OR trainee medical officer performance OR resident performance OR registar performance OR doctor performance OR clinical performance OR trainee clinical performance OR resident clinical performance OR registrar clinical performance OR doctor clinical performance OR specialty training success OR specialty training performance OR specialty training clinical performance). Online Resource 1 provides the search strings employed for each database.

Article screening was completed in duplicate and instances of disagreement were resolved through a third reviewer’s assessment. The evaluation was conducted firstly on titles and abstracts before full text review. The inclusion criteria applied were: (1) English language; (2) systematic review or meta-analysis, (3) includes pre-specialty training applicants, (4) assesses the selection criteria used to select, or characteristics of, pre-specialty training applicants in predicting performance during/after specialty training, and (5) available in full text. Articles were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Quality analysis of the included articles was performed in duplicate and completed using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses.

2.2 Quality analysis

Prior to data extraction, quality analysis was completed in duplicate using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses. Table 2 in Online Resource 1 shows the critical appraisal results for each included study; 10/10 studies were appraised to be of sufficient quality for inclusion; however, 2/10 studies did not report their quality appraisal tool and 2/10 studies were not clear whether quality appraisal was completed in duplicate. Three of ten studies did not report methodology to minimise errors in data extraction, 6 did not report the risk of publication bias and 8 did not use a statistical strategy to combine results but rather reported their findings with narrative synthesis.

2.3 Data extraction and analysis

A standardised form, the JBI Data Extraction Form for Review for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses, was used for data extraction of the included studies. Data were extracted in duplicate, and overlap of primary studies between multiple included syntheses were screened for and deduplicated to avoid double counting. Data of interest for extraction included study characteristics (type of study, recruitment period, objectives, setting, interventions of interest, sources and databases searched, year range of included studies, number of included studies, types of included studies, country of origin of included studies, number of participants, number of studies included, year range of data from included studies, appraisal instrument used, appraisal rating, synthesis/analysis method used, outcome assessed, significance and future direction of study), research characteristics (publications, presentations, higher academic degrees), rural exposure (during formative years, during university, postgraduate), clinical experience (clerkship performance, reference letters, medical school class rank, Dean’s letter, personal statement, post-graduate experience in medicine/surgery (pre-training)), academic performance (medical school performance, United States Medical Liscencing Examination (USMLE) Step 1, USMLE Step 2, the US National Board Medical Examination (NBME), scholarships and grants, Alpha Omega Alpha (AOA) award, other prizes and awards, participation in courses, attendance at scientific conferences, committee positions held), technical aptitude tests, other activities (involvement in sports, music, volunteering, leadership positions held, teaching beyond the ward, gaming), diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) characteristics, live assessment scores (traditional interview), multiple mini interviews (MMI), situational judgment test (SJT).

Data were analysed by recording the reported strength of association of a selection criteria’s prediction of performance, across all performance outcomes reported in the included syntheses (Table 3 in Online Resource 1). Finally, findings were summarised for the three most commonly reported performance outcomes: in-training-examination, end-of-training examination, and in-training evaluation (Table 1).

3 Results

3.1 Search results and study characteristics

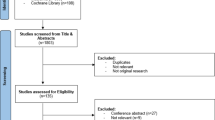

The search strategy provided 1168 studies (see Fig. 1). Following review of titles and abstracts, 39 studies were reviewed in full text. There were 10 studies included in this review: 8 systematic reviews, 1 meta-analysis and 1 combined systematic review and meta-analysis. The characteristics of the included articles are summarised in Table 1 in Online Resource 1.

3.2 Findings indicating a selection criteria’s prediction of performance

Our findings indicate that the objective selection criteria with the most evidence supporting the prediction of future performance include medical school performance [8,9,10,11,12,13,14], USMLE Step 1 [8,9,10,11,12,13,14], USMLE Step 2 [8,9,10,11, 14], and NBME [9, 11]. We report that 67.1% (49/73), 74.3% (75/101), 83.9% (52/62), and 93.3% (28/30) of all findings respectively indicate prediction of future performance. Cognitive tests, particularly those named PicSOR, ADTRACK2, grooved pegboard, the mental rotation test, and human basic resources also showed promise in predicting surgical technical performance [15]. The predictive validity of subjective selection criteria including Dean’s letter [8,9,10], traditional interview scores [8,9,10,11,12, 14], and SJT scores [10, 12, 16] were also supported to varying extents. Clerkship performance [9,10,11,12, 14], reference letters [9,10,11,12,13,14], and medical school class rank [10,11,12, 14] were of equivocal validity, with 39.8% (35/68), 48.6% (17/35) and 48.7% (19/39) of all findings respectively indicating prediction of future performance. Whilst involvement in sports [10,11,12, 14], post graduate experience in medicine or surgery (pre-training) [12], and MMI [10, 12], showed positive predictive results, there is not enough evidence to make an informed conclusion about their prediction of future performance. We report that our findings show a vast majority of non-predictive findings for research publications, 20% (7/35); AOA, 32.8% (20/61); music, 20% (1/5); volunteering, 10% (1/10); leadership positions, 9.1% (1/11); and gaming experience, 33.3% (2/6). Higher academic degrees (0/11), personal statement (0/3) and DEI (0/2) report no positive predictive findings. Included studies did not report evidence for research presentations, rural exposure, scholarships/grants, prizes/awards, participation in courses, attendance at scientific conferences, committee positions held, and teaching beyond the ward predicting future performance or not.

Table 1 represents the proportion of the respective selection criteria’s positive predictive findings for predicting performance in the in-training examination, end-of-training examination, and in-training evaluation.

4 Discussion

4.1 Utility of selection criteria for predicting performance during and after specialty training

Our findings indicate that the criteria used for selecting applicants into specialty training programs has varying evidence supporting its prediction of future performance during specialty training and beyond. Data extracted from included articles are summarised in Table 3 in Online Resource 1. A summary of the selection criteria with the largest evidence base, and their prediction of specific outcomes of performance is summarised in Table 1.

Our findings indicate that the objective selection criteria with the most evidence, which predominantly arises from the US, supporting the prediction of future performance include medical school performance, USMLE Step 1, USMLE Step 2, and NBME. The USMLE is an examination undertaken by US medical students that assesses their medical knowledge and provides residency program selectors with an objective measure of an applicant’s knowledge base [17]. The USMLE 1 has a specific focus on a candidate’s understanding of pathology, physiology and pharmacology, whereas the USMLE 2 is designed to assess a candidate’s clinical medicine understanding [18]. The superior predictive ability of USMLE 2 compared to USMLE 1 may be attributed to its specific focus on assessment of an applicant’s clinical medicine understanding and application as opposed to USMLE 1’s focus on foundation sciences knowledge [18]. USMLE 2 performance may be more closely aligned to actual performance given its contents are more closely aligned with clinical medicine compared to USMLE 1 [19]. Additionally, data extraction indicated that USMLE had a poor predictive ability of end-of-training examination performance. This may be attributed to the difference in content of the USMLE 2 exam and the typical end-of-training exams. The majority of end-of-training exams have an objective structured clinical examination component that is notably different in nature when compared to standardised USMLE 2 written exams [20]. Candidate’s strong performance in the written USMLE evidently may not correlate with an inherently different clinical examination that they are exposed to during end-of-training examinations and hence, may represent a poor predictive value [21]. Similarly to the USMLE 2, the NBME aims to assess clinical skills and also foundational sciences knowledge relevant to a specific clinical clerkship [22]. The predominant focus on an applicant’s clinical skills and ability to apply these during a clinical clerkship, which aims to emulate a professional environment that a candidate would likely experience during training, may explain why NBME performance is so strongly predictive of future performance. Although the USMLE 1 has a relatively high predictive value, its predominant focus on assessment of foundational sciences as opposed to clinical medicine, may explain its comparatively lower predictive value when assessed against the USMLE 2 and NBME [23]. Interestingly, whilst we found that the NBME had significantly greater positive predictive value for end-of-training examinations when compared to the USMLE 2, a previous study by Zahn et al. report strongly positive prediction for both USMLE and NBME [24].

The predictive validity of subjective selection criteria including Dean’s letter [8,9,10], traditional interview scores [8,9,10,11,12, 14], and SJT scores [10, 12, 16] were also supported to varying extents. Dean’s letters had 92.0% (23/25) of findings indicating prediction; however, this association was reported to be of weak strength across the three included that reported this selection criteria. Traditional interview scores had 72.4% (21/29) of all findings supporting prediction of performance. However, two studies found no positive prediction value of the traditional interview on end-of-training examination performance. There was, however, an 85.7% proportion of positive findings when assessing correlation with positive in-training evaluation performance. These findings thereby suggest that this particular performance outcome may have a variable predictive value of how a trainee will perform throughout their training. One systematic review analysed the predictive validity of SJTs for future performance, and found that 85.7% (12/14) of findings support its prediction of construct relevant outcomes of performance, amongst other findings.

4.2 Limitations of included articles

Our reported findings must be viewed in the context of the reported limitations of the included syntheses from which they were obtained. Three out of ten included syntheses did not report the number of included participants from their primary studies analysed. Additionally, whilst two of ten included studies used statistical analysis to determine strengths of associations of selection criteria and future performance prediction, other studies described prediction as a binary outcome in narrative form. A key recurring limitation reported by our included articles was the quality of the primary articles analysed, particularly a high reported risk of bias amongst numerous primary articles in five of our included syntheses [9, 11, 13, 16, 25].

Various included studies reported heterogeneity, which whilst this was an indication for the present research to consolidate and summarise findings, this should be considered when interpreting the results of our umbrella review. Webster et al. reported considerable heterogeneity with an I2 value of 96.5% across all extracted data. Zuckerman et al. reports that there was significant heterogeneity in selection criteria, outcomes, specialties and institutions assessed [14]. Kenny et al. reported most findings had considerable or substantial levels of heterogeneity due to outcome variability across their included primary studies. An I2 value for each synthesis of selection criteria predicting performance is supplied in Table 3 of Online Resource 1. Lipman et al. reported they could not complete statistical analysis due to the heterogeneity of the data. A source of heterogeneity that is common to all the included syntheses includes the broad range of, and occasionally undefined, performance outcomes. In-training and end-of-training examinations, and in-training evaluation reports vary depending on the specialty, institution and location of the training program. An additional source of heterogeneity was that 9/10 included syntheses combined their findings across a range of multiple specialties. Six studies, however, interpreted their results solely for surgical specialties [8, 11, 13,14,15, 25], whilst two studies [11, 14] aimed to analyse findings for a singular specialty. Bowe et al. included only 6 otolaryngology articles and thus did not generate enough evidence for robust conclusions. Similarly, Zuckerman et al. had to extend the surgical specialty inclusion criteria beyond neurosurgery to generate enough valid articles to review. Various included syntheses [8, 11,12,13,14,15] did not comment on the presence of heterogeneity within their reviews. The presence of statistical heterogeneity reduces the confidence of the umbrella review to convey the significance of the reported selection criteria that predict performance during and after specialty training, especially when combining results for synthesis. As a result, we have increased the interpretability of our findings by reporting the proportion of all findings for a given selection criteria that represent positive prediction of performance. This provides a clear assessment of strength of prediction for that selection criteria to the reader.

4.3 Limitations of our umbrella review

Our umbrella review presents various limitations for discussion. The main limitation of our study is that varying outcomes of performance during and after specialty training were reported by our included syntheses across multiple specialties. Additionally, findings were often combined across specialties. This reduced the generalisability of our findings. The selection of applicants into training programs, however, is not just based on predicting future performance. Applicants into Australian training programs, for example, are often additionally selected based on diversity, equity, and inclusion protocols, and for the extent to which they will be able to work in rural areas. This allows for greater access of healthcare to a larger proportion of the community.

4.4 Significance of our findings and future work

Entrance into specialty training programs is a competitive process, and various selection methods are utilised internationally. Applicants are often selected into programs based on selection criteria that aim to predict performance during and after specialty training. Current syntheses providing evidence supporting this prediction, however, remains mostly equivocal. The present umbrella review reduces the heterogeneity in existing synthesies and provides strong conclusions on performance predictive criteria and pathways forward. Our findings indicate that the selection criteria that are most strongly supported by the literature in their use of predicting performance include medical school performance, USMLE Step 1 scores, USMLE Step 2 scores, NBME scores and SJT scores. However, the recent update of the USMLE Step 1 from a graded score to pass or fail score[26] limits its application in selection frameworks, unless scores are made available to selection committees.

This umbrella review provides a framework on the current base of literature on predicting future performance during and after specialty training with which to engage in robust future studies. Selection into medical and surgical specialties is an ever-developing area of research, and institutions should continually reassess and update selection criteria using evidence-based approaches. Future work should attempt to focus on describing consistent outcomes of performance during and after specialty training to improve generalisability and heterogeneity. We acknowledge that this is difficult given the inherent variation across specialty training programs, however, attempts at assessing consistent outcomes will provide reduced heterogeneity of findings. Both objective outcomes, including in-training and end-of-training examinations, and subjective outcomes, including faculty in-training evaluations should be the outcomes of focus. Additionally, outcomes of performance beyond specialty training should be identified and focused upon. Consideration of methods to incorporate patient outcomes into indicators of subsequent performance metrics is also warranted. Future studies should clearly delineate which specialty the results of performance prediction pertain to, allowing for future syntheses of primary studies to outline clear paths forward for each specialty.

Currently, the evidence pertaining to applicant selection is most robust for objective criteria of academic and clinical performance, however applicants should be selected into medical and surgical training programs also based on non-academic criteria. As a result, future work needs to focus on building up the evidence base to the extent to which nonacademic criteria including rural exposure, DEI factors, and involvement in sports, music, volunteering, leadership, teaching, and gaming predict future performance. It is also important for future studies to consider that applicants are not just selected into training based on their predicted performance. Other non-performance based outcomes to be explored may include teamwork skills, professionalism, development and maintenance of the doctor-patient relationship, and the interactions of the trainee with the healthcare system at large. Whilst innate technical ability for surgery is an important consideration for surgical specialties, its prediction of future performance remains underreported. Technical aptitude tests including PicSOR, mental rotation test, and human basic performance resources, however, show promise, and future work should further validate its prediction of future surgical technical performance [25].

4.5 Conclusion

The present umbrella review, following a synthesis of 10 included articles, reports that the selection criteria with the best available evidence in predicting performance during and after specialty training were medical school performance, USMLE Step 1 scores, USMLE Step 2 scores, NBME scores and SJT scores. The present umbrella review clarifies and builds on the current evidence base by providing robust conclusions regarding trainee performance prediction for use in selection of applicants into specialty training. Future research in this vital area is required to promote the selection of the best possible candidates to deliver care for patients in the future. Such future research may benefit from a focus on consistent utilisation of performance outcomes.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Mowery YM. A primer on medical education in the United States through the lens of a current resident physician. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(18):270. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.10.19.

Muecke T, Bacchi S, Casson R, Chan WO. Building a bright future: discussing the weighting of academic research in standardized curriculum vitae for Australian Medical and Surgical Specialty Training College entrance. ANZ J Surg. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.18513.

Muecke T, Bacchi S, Casson R, Chan WO. Building the workforce of tomorrow: the weighting of rural exposure in standardised curriculum vitae scoring criteria for entrance into Australian specialty training programs. Aust J Rural Health. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.13131.

Daniel M, Gottlieb M, Wooten D, Stojan J, Haas MRC, Bailey J, et al. Virtual interviewing for graduate medical education recruitment and selection: a BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 80. Med Teach. 2022;44(12):1313–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2022.2130038.

Berardi-Demo L, Cunningham T, Dunleavy DM, McClure SC, Richards BF, Terregino CA. Designing a situational judgment test for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2024;99(2):134–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000005471.

Mitsouras K, Dong F, Safaoui MN, Helf S. Student academic performance factors affecting matching into first-choice residency and competitive specialties. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1669-9.

Zastrow RK, Burk-Rafel J, London DA. Systems-level reforms to the US resident selection process: a scoping review. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(3):355–70. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-20-01381.1.

Schaverien MV. Selection for surgical training: an evidence-based review. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(4):721–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.02.007.

Kenny S, Mcinnes M, Singh V. Associations between residency selection strategies and doctor performance: a meta-analysis. Med Educ. 2013;47(8):790–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12234.

Lipman JM, Colbert CY, Ashton R, French J, Warren C, Yepes-Rios M, et al. A systematic review of metrics utilized in the selection and prediction of future performance of residents in the United States. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15(6):652–68. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00955.1.

Bowe SN, Laury AM, Gray ST. Associations between otolaryngology applicant characteristics and future performance in residency or practice: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(6):1011–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599817698430.

Roberts C, Khanna P, Rigby L, Bartle E, Llewellyn A, Gustavs J, et al. Utility of selection methods for specialist medical training: a BEME (best evidence medical education) systematic review: BEME guide no. 45. Med Teach. 2018;40(1):3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1367375.

Maan ZN, Maan IN, Darzi AW, Aggarwal R. Systematic review of predictors of surgical performance. Br J Surg. 2012;99(12):1610–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.8893.

Zuckerman SL, Kelly PD, Dewan MC, Morone PJ, Yengo-Kahn AM, Magarik JA, et al. Predicting resident performance from preresidency factors: a systematic review and applicability to neurosurgical training. World Neurosurg. 2018;110:475-484.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.11.078.

Louridas M, Szasz P, De Montbrun S, Harris KA, Grantcharov TP. Can we predict technical aptitude? A systematic review. Ann Surg. 2016;263(4):673–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001283.

Webster ES, Paton LW, Crampton PES, Tiffin PA. Situational judgement test validity for selection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ. 2020;54(10):888–902. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14201.

Wu W, Garcia K, Chandrahas S, Siddiqui A, Baronia R, Ibrahim Y. Predictors of Performance on USMLE Step 1. The Chronicles. 2021;9:63–72. https://doi.org/10.12746/swrccc.v9i39.813.

Lombardi CV, Chidiac NT, Record BC, Laukka JJ. USMLE step 1 and step 2 CK as indicators of resident performance. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):543. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04530-8.

Sharma A, Schauer DP, Kelleher M, Kinnear B, Sall D, Warm E. USMLE step 2 CK: best predictor of multimodal performance in an internal medicine residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(4):412–9. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00099.1.

Brennan PA, Croke DT, Reed M, Smith L, Munro E, Foulkes J, et al. Does changing examiner stations during UK postgraduate surgery objective structured clinical examinations influence examination reliability and candidates’ scores? J Surg Educ. 2016;73(4):616–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.01.010.

Sajadi-Ernazarova K, Ramoska EA, Saks MA. USMLE scores do not predict the clinical performance of emergency medicine residents. MedJEM. 2020. https://doi.org/10.52544/2642-7184(1)2001.

Matus AR, Matus LN, Hiltz A, Chen T, Kaur B, Brewster P, et al. Development of an assessment technique for basic science retention using the NBME subject exam data. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):771. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03842-5.

Belovich AN, Bahner I, Bonaminio G, Brenneman A, Brooks WS, Chinn C, et al. USMLE step-1 is going to pass/fail, now what do we do? Med Sci Educ. 2021;31(4):1551–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-021-01337-4.

Zahn CM, Saguil A, Artino AR Jr, Dong T, Ming G, Servey J, et al. Correlation of national board of medical examiners scores with united states medical licensing examination step 1 and step 2 scores. Acad Med. 2012;87(10):1348–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826a13bd.

El Boghdady M, Ewalds-Kvist BM. The innate aptitude’s effect on the surgical task performance: a systematic review. Updates Surg. 2021;73(6):2079–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-021-01173-6.

Alnahhal KI, Lyden SP, Caputo FJ, Sorour AA, Rowe VL, Colglazier JJ, et al. The USMLE® STEP 1 pass or fail era of the vascular surgery residency application process: implications for structural bias and recommendations. Ann Vasc Surg. 2023;94:195–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2023.04.018Z.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge both The University of Adelaide, and the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Stephen Bacchi is supported by a Fulbright Scholarship (funded by The Kinghorn Foundation). Ethics approval or review by other institutional bodies was not required for this umbrella review. The authors have no other conflicting interests to disclose.

Funding

Australian Government,The University of Adelaide, Fulbright U.S. Scholar Program

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M wrote the main manuscript text. T.M, A.R, H.W, J.T and D.J completed data collection and analysis. S.B, R.C and W.C supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript and made edits.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muecke, T., Rao, A., Walker, H. et al. Specialists of tomorrow: an umbrella review of evidence supporting criteria used in medical and surgical specialty training selection processes. Discov Educ 3, 119 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00205-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00205-8