Abstract

Introduction

Medical interpreters are crucial to ensure fair and high-quality healthcare for patients with limited English proficiency (LEP). Despite the need to use high-quality medical interpreters to communicate with LEP patients, medical schools often do not adequately educate their students on how to work with interpreters.

Aims

This study seeks to investigate the efficacy of using peer-assisted learning to teach medical students how to properly use medical interpreters. Moreover, the study strives to elucidate if an interactive peer-led model can be an effective teaching modality to train medical students about the basics of using medical interpreters.

Methods

A pre- and post-training design was utilized to investigate the efficacy of peer-assisted learning in teaching medical students how to use interpreters. Second year medical students led a two-part workshop consisting of the following: (1) a didactic training session and (2) a practical session where learners interacted with Spanish-speaking standardized patients through an interpreter. Pre-training and post-training responses to survey questions were analyzed to determine changes in student comfort, confidence, and knowledge of best practices when using a medical interpreter.

Results

There was a statistically significant increase in comfort and confidence with using interpreters after receiving peer-assisted training.

Conclusions

A peer-led didactic training followed by an interactive training session can increase student comfort and confidence with using medical interpreters in clinical settings. Peer-assisted-learning may be an effective way to teach some of the best practices of using medical interpreters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the United States (U.S.), over 60 million people over the age of five speak a language other than English at home. Of this population, more than 37 million people speak Spanish at home. Almost half of this population self-rated themselves as speaking English less than “very well” between the years 2018 and 2022 [1].Language barriers are especially prevalent in California, where a large portion of the population speaks Spanish. The rate of Spanish-speaking physicians to Spanish-speaking patients in the state is 62.1 to 100,000, making access to language-concordant care difficult for this population of patients [2]. Language barriers are a significant impediment to receiving equitable healthcare in the United States [3]. Limited English Proficiency (LEP) patients are more likely to be dissatisfied with their care [4], are at higher risk of not adhering to treatment recommendations [5, 6], and are at greater risk for medical error [7]. LEP patients are more likely to be misunderstood by their physicians [8], which increases patient readmissions and length of stay [9].

Given the prevalence of patients who speak languages other than English, many healthcare providers are tasked with overcoming potential language barriers between themselves and their patients. Language-concordant care can improve trust levels between patients and physicians and promote health equity [10]. However, in situations where language-concordant care is not achievable, medical interpreters are a viable alternative. Using medical interpreters in clinical settings has been shown to improve patient outcomes when treating LEP patients [11,12,13]. However, even with interpreting resources readily available in healthcare settings, interpreters are underutilized when interacting with LEP populations.

To improve the frequency and quality of medical interpreter use, U.S. medical schools have expanded academic discourse about the best practices for interpreter use. Studies have shown that medical student and resident workshops can improve student confidence in working with qualified interpreters[12]. Others have shown that training physicians and medical students how to use interpreters when caring for LEP patients can lead to improved healthcare outcomes [14].

Training student doctors how to use interpreters during the early stages of medical education can equip future physicians with skills to navigate linguistic barriers and provide culturally sensitive care throughout their career. While a majority of medical schools offer training on using a medical interpreter, the amount of training on this subject only comprises a small portion of the medical school curriculum. Although multiple studies have investigated training 3rd and 4th year medical students to use medical interpreters, the impact of such training modules for 1st and 2nd year students has not been thoroughly investigated [15]. Moreover, to our knowledge, the role of peer-assisted-learning in teaching fundamentals of using medical interpreters has not been studied. Currently, all studies analyzing workshops on using medical interpreters have been run by faculty or trained medical interpreters.

One proposed benefit of peer-assisted learning is a smaller knowledge gap between learner and instructor. Because of this, learners often feel more comfortable asking questions or engaging in conversation with instructors on the topic being taught. Moreover, in a peer-assisted learning model, instructors are more likely to explain topics at a level appropriate for the learner due to smaller differences in training between learner and instructor [16]. Literature shows that peer-assisted learning can encourage group discussions, collaborative problem-solving, and an improved learning environment [17]. In regards to its use in medical education, peer-assisted learning has been shown to be effective at teaching students technical skills such as ultrasound, injections, spinal manipulation, and surgical knot tying [18,19,20]. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that peer-assisted learning in combination with simulation-based training techniques can be an effective teaching modality. Specifically, one study that involved peer-led simulation successfully taught students how to take a history, improved their understanding of pathophysiology, and helped them appreciate interprofessional interactions [21]. Moreover, a combination of peer-assisted learning and simulation-based techniques was effective in improving student proficiency in echocardiography [22]. However, to our knowledge, the role of peer-assisted learning in combination with simulation-based training to teach students how to use medical interpreters has yet to be studied.

We believe that it is important to investigate whether peer-assisted learning combined with simulation-based training can be an effective method of teaching students how to use medical interpreters in clinical settings. To address this question, we created a student-led workshop for 1st and 2nd year medical students that combined didactic training with simulation-based training. This study hopes to address disparities in healthcare by training students to navigate linguistic barriers that exist between themselves, LEP patients, and interpreters. The pre-training and post-training survey results gathered from this study and the structure of the two-fold training sessions are also aimed at providing students with training early in medical school so that they are prepared to interact with LEP patients throughout their careers.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and context

Four second-year medical students and one faculty member at the California University of Science and Medicine designed a workshop to teach first-year (M1) and second-year (M2) medical students how to use interpreters. Approval was obtained from the school’s institutional review board prior to conducting the study (HS-2022–09). M1 and M2 students were recruited to attend the training session via class-wide emails. Participation in the study was optional and all participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study. Because the study was designed to last no longer than 90 min, demographic data was not collected on study participants to shorten the time needed to complete the survey and the workshop. The workshop consisted of two parts: 1) a didactic PowerPoint presentation and 2) a practical session in which attendees participated in a simulated patient encounter with a Spanish-speaking standardized patient and an interpreter.

2.2 Instruments

A pre- and post-training survey design was utilized. Before the didactic session, attendees completed a survey to gauge self-perceived comfort, confidence, and knowledge of best practices regarding using interpreters (Appendix 1). Surveys used statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). The survey was designed by the authors and adapted from a study by Coetzee et al. [23]. The survey consisted of a series of correct or incorrect statements regarding best practices for using an interpreter (Appendix 2). Best practices were defined by guidelines published by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) [24]. Additionally, patients were asked to rate the statements “I feel comfortable communicating with my patient via an interpreter” and “I feel confident communicating with my patient while using an interpreter.”

2.3 Didactics workshop session

The PowerPoint presentation was designed by the authors and included details on proper etiquette when using a medical interpreter. Guidelines for interpreter use were derived from an article published by the AAFP. The PowerPoint covered the benefits of and guidelines for effectively using in-person, telephone, and video interpreter services. Specifically, the presentation highlighted the differences between interpreters and translators, covered the implications of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Title VI on care for LEP patients, and used a case example to demonstrate the consequences of failing to use a professional medical interpreter when taking a patient history. The case example exhibited how assumptions by physicians about the meaning of the Spanish word “intoxicado” severely negatively impacted patient care. The presentation also used pictures and diagrams to show students where to place themselves in relation to the patient and medical interpreter when in a clinical examination room. Furthermore, the didactic session of the workshop detailed common errors when using a medical interpreter and specific corrections students should incorporate into their practice to address these errors.

Two M2s involved in the design of the study presented the PowerPoint to a group of 33 M1 and M2s. At the end of the PowerPoint presentation, a practicing family medicine physician spoke to study participants about the role of interpreters in his practice. Students were allowed to ask questions of both the student presenters and the family medicine physician after the PowerPoint presentation.

2.4 Practical session workshop session

Immediately following the PowerPoint presentation, attendees of the lecture were encouraged to attend a simulated patient encounter with a Spanish-speaking patient. Attendance in the practical session was not mandatory. However, attending the lecture was a prerequisite for attending the simulated patient encounter. Nineteen of 33 students elected to participate in the simulated patient encounter. Students were broken into groups of four or five to interact with Spanish-speaking standardized patients. Five bilingual students were recruited to serve as interpreters in these patient encounters. Standardized patients were instructed to present with a chief complaint of sore throat and were given guidelines regarding timing, onset, character of pain, and associated symptoms. Interpreters were instructed to interpret from English to Spanish word-for-word as well as possible. Moreover, interpreters were instructed to follow workshop attendee instructions regarding positioning during the patient encounter. Students were given 15 min to participate in the patient encounter.

2.5 Data collection and analysis

Following the patient encounter, the post-training survey was administered. It contained the same questions in the survey collected before the workshop. Pre- and post-training responses for each attendee were matched using unique identifiers. Of the 33 students that completed the pre-training survey, 19 students completed the post-training survey. For the 19 students who completed both pre- and post-training surveys, differences in pre- and post-training responses were analyzed using a one-tailed paired t-test with alpha set at 0.05. Pre-workshop survey responses from students who did not attend the simulated patient encounter were excluded from statistical analyses. All analyses were conducted in Microsoft Excel Version 16.70 (2023). Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the study design.

3 Results

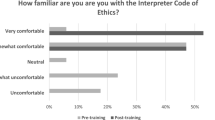

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the workshop to train medical students on how to use medical interpreters. In response to the statement, “I feel comfortable communicating with my patient via an interpreter,” student Likert responses averaged 3.31 before the training session and improved to 4.37 following the training session (Fig. 2; p < 0.01). Similarly, in response to the statement, “I feel confident in communicating with my patient while using an interpreter,” average Likert responses improved from 3.53 prior to the training session to 4.47 following the training session (Fig. 3; p < 0.01). Students were asked to respond to a series of statements about best practices of using a medical interpreter that were either correct or incorrect. In response to the incorrect statement, “Family members or friends are the best people to use as interpreters,” average Likert responses changed from 2.10 pre-intervention to 1.36 post-intervention (Fig. 4; p < 0.01). Similarly, in response to the incorrect statement, “It is appropriate to use family members or friends as interpreters in non-emergency situations,” the pre-training Likert scale average was 2.74 while the post-training Likert scale average was 1.79 (Fig. 5; p = 0.01). Prior to the training, Likert responses to the incorrect statement “The best place to have the interpreter is between you and your patient” averaged 2.74 while the post-training averages were 2.05 (Fig. 6; p = 0.08) Moreover, after receiving training, students were more likely to agree with the correct statement “When speaking through an interpreter, it is important to slow down and use short sentences,” although this change was not statistically significant. In response to this statement, the pre-training Likert scale average was 4.26 while the post-training Likert scale average was 4.68 (Fig. 7; p = 0.056). Similarly, a small, but statistically insignificant increase was seen in response to the correct statement, “When using an interpreter, the clinician should address the patient directly.” In response to this statement, the pre-training Likert average was 4.73 while the post-training Likert average was 4.89 (Fig. 8; p = 0.08).

4 Discussion

Our study indicates that a student-led workshop can build medical student self-perceived comfort and confidence in using interpreters in clinical settings. Prior to receiving training, 42% of medical students surveyed felt comfortable using a medical interpreter in a patient encounter compared to 95% of medical students after the workshop was conducted. Moreover, confidence and comfort levels statistically increased after receiving training (p < 0.01). Increased self-perceived comfort and confidence suggest students who undergo training may be more willing to use interpreters during their clinical rotations and beyond. This can potentially increase access to care for patients who speak English with limited proficiency.

To better assess student understanding of best practices of using an interpreter, students were asked to respond to various correct or incorrect statements about using interpreters in clinical settings. Responses to these questions indicated that many students had a baseline understanding of best practices for using interpreters before starting training. For example, in response to the pre-workshop survey statements, “When speaking through an interpreter it is important to slow down and use short sentences” and “When using an interpreter, the clinician should address the patient directly,” 16 of 19 (84%) and 18 of 19 (95%) students responded with either agree or strongly agree, respectively. Similarly, in response to the statement, “Family members or friends are the best people to use as interpreters,” 13 of 19 (68%) students responded with either disagree or strongly disagree. However, other subtleties of using interpreters may not be common knowledge to students. In response to questions regarding the positioning of interpreters, there was a higher variance in pre-workshop answers compared to other survey questions (Fig. 6). With training, students shifted toward responding correctly to posed statements regarding interpreter positioning, although this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08). These data suggest that future workshops may benefit from a pre-training survey analyzing student understanding of working with an interpreter. By doing so, training sessions can be directed at improving misconceptions and filling gaps in knowledge.

A previous study by Coetzee et al. demonstrated that a one-week, faculty-led course on medical interpreters improved 3rd and 4th-year student self-reported confidence in working with interpreters.23 Moreover, this study showed that students found training applicable to their clerkship experiences and patient encounters. While learning to use a medical interpreter during any stage in medical education can prepare physicians to interact with LEP patients in their careers, training in preclinical years provides the benefit of allowing students to extend care to LEP patients throughout their clerkship experience. Our results expand on the findings of Coetzee et al. We suggest that using an interactive workshop to train medical students in their preclinical years is similarly effective at improving student self-reported comfort and confidence when working with medical interpreters.

The 90 min duration of the workshop in our study is shorter than other workshops that train students to become or use interpreters, which ranged from 6 h to one week [23, 25]. Moreover, in contrast to these studies, which were led by faculty and formally incorporated into curricula, our study was an optional student-run event. The optional, student-run nature of our workshop has the advantage of incorporating training on using medical interpreters into a densely packed medical school curriculum that may not otherwise be able to accommodate formal training on using medical interpreters. For schools that do not have room to add training to an already-filled curriculum, our study suggests that an optional workshop can be an effective way to provide training to at least a subset of the student population. However, as our study showed, optional workshops may not reach most of the student population, representing a disadvantage of making training voluntary.

Our study has several limitations. First, our study was conducted with a student population at one medical school in San Bernardino, California. Because many patients in the area only speak Spanish, students at our institution may be more likely to participate in patient encounters that require an interpreter than students who study elsewhere. Future studies centered on teaching students how to use medical interpreters should include medical schools throughout California and the U.S. These studies would help elucidate whether school-specific biases or regional biases affected student survey results. While this limitation exists, it is important to note that conducting this study at a medical school that is partnered with a hospital which serves many LEP patients allows for students to gain valuable, applicable knowledge that can be applied during clinical rotations. Moreover, our study is a convenience sample. As such, recruiting in our study may have favored workshop attendance by students who were motivated to learn to use interpreters and may not represent the general student population. Given this workshop was initially offered as an optional extracurricular training, we expected most students to be motivated to attend our workshop. Similarly, a lack of demographic data collected precludes analysis from identifying any potential confounding variables, such as prior experience working with or serving as an interpreter and previous training on interpreter use. Demographic data would help clarify the role of previous exposure to LEP patients on workshop efficacy. As we continue to implement this training in future classes, we plan to collect demographic data to better understand our survey results. Furthermore, comfort and confidence are not measures of competency. Although our survey includes questions that attempt to assess student knowledge about the logistical aspects of using interpreters, these portions of the survey were self-created and have not been previously validated. Additionally, our post-training survey was administered immediately after training and can benefit from follow-up surveys administered at later points in time. Despite the limitations of our study, we provide preliminary evidence that a student-run workshop can improve medical student self-reported comfort and confidence in interacting with interpreters. Moreover, our data suggest that our training model can be effective in teaching students techniques to maximize the effectiveness of using a medical interpreter.

5 Conclusion and future directions

Our study showed that a peer-to-peer didactic session followed by an interactive training model can improve student self-reported confidence and comfort when working with professional interpreters. This parallels a similar study demonstrating that peer-led rounds between junior and senior medical students can improve student-reported confidence and comfort levels when rounding at the bedside [26]. Another similar study showed that near-peer led simulation training improved student confidence and comfort when interacting with post-op and post-stroke patients [27]. Together, these results reinforce that peer-assisted learning combined with interactive training is effective at increasing learner comfort and confidence.

Future research should adapt the current proposal for residents and attending physicians. Furthermore, this training module could incorporate interactive elements such as case studies, role-playing exercises, and small-group discussions to facilitate a deeper understanding of the nuances of interpreter use in healthcare settings. Increasing training for medical students and physicians regarding interactions with LEP patients has the potential to improve access to care to underserved communities across the United States.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: United States. Published 2021. Accessed 20 Mar 2023. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221

CMA to celebrate National Latino Physician Day on October 1. California Medical Association.

Green AR, Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza ATR, Massagli MP, Phillips RS, Iezzoni LI. Interpreter services, language concordance, and health care quality. Experiences of Asian Americans with limited English proficiency. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1050–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0223.x.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited english proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(S2):324–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0340-z.

Shen Q, Cordato DJ, Chan DKY, Kokkinos J. Comparison of stroke risk factors and outcomes in patients with English-speaking background versus non-English-speaking background. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;24(1–2):79–86. https://doi.org/10.1159/000081054.

Wang NE, Kiernan M, Golzari M, Gisondi MA. Characteristics of pediatric patients at risk of poor emergency department aftercare. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(8):840–7. https://doi.org/10.1197/j.aem.2006.04.021.

Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, et al. Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):6–14. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.1.6.

Al Shamsi H, Almutairi AG, Al Mashrafi S, Al KT. Implications of language barriers for healthcare: a systematic review. Oman Med J. 2020;35(2):e122–e122. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2020.40.

Levas MN. Effects of the limited english proficiency of parents on hospital length of stay and home health care referral for their home health care-eligible children with infections. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(9):831. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.61.

Molina RL, Kasper J. The power of language-concordant care: a call to action for medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):378. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1807-4.

Bischoff A, Perneger TV, Bovier PA, Loutan L, Stalder H. Improving communication between physicians and patients who speak a foreign language. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(492):541–6.

Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited english proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x.

Jacobs EA, Shepard DS, Suaya JA, Stone EL. Overcoming language barriers in health care: costs and benefits of interpreter services. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):866–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.5.866.

Lopez Vera A, Thomas K, Trinh C, Nausheen F. A case study of the impact of language concordance on patient care, satisfaction, and comfort with sharing sensitive information during medical care. J Immigr Minor Health. 2023;25(6):1261–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-023-01463-8.

Pinto Taylor E, Mulenos A, Chatterjee A, Talwalkar JS. Partnering with interpreter services: standardized patient cases to improve communication with limited english proficiency patients. MedEdPORTAL. 2019. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10826.

Bulte C, Betts A, Garner K, Durning S. Student teaching: views of student near-peer teachers and learners. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):583–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701583824.

Hodgson Y, Benson R, Brack C. Student conceptions of peer-assisted learning. J Furth High Educ. 2015;39(4):579–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.938262.

Knobe M, Münker R, Sellei RM, et al. Peer teaching: a randomised controlled trial using student-teachers to teach musculoskeletal ultrasound. Med Educ. 2010;44(2):148–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03557.x.

Weyrich P, Celebi N, Schrauth M, Möltner A, Lammerding-Köppel M, Nikendei C. Peer-assisted versus faculty staff-led skills laboratory training: a randomised controlled trial. Med Educ. 2009;43(2):113–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03252.x.

Rogers DA, Regehr G, Gelula M, Yeh KA, Howdieshell TR, Webb W. Peer teaching and computer-assisted learning: an effective combination for surgical skill training? J Surg Res. 2000;92(1):53–5. https://doi.org/10.1006/jsre.2000.5844.

Nunnink L, Thompson A, Alsaba N, Brazil V. Peer-assisted learning in simulation-based medical education: a mixed-methods exploratory study. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjstel-2020-000645.

Kühl M, Wagner R, Bauder M, et al. Student tutors for hands-on training in focused emergency echocardiography – a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):101. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-101.

Coetzee D, Pereira AG, Scheurer JM, Olson AP. Medical student workshop improves student confidence in working with trained medical interpreters. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:238212052091886. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120520918862.

Juckett G, Unger K. Appropriate use of medical interpreters. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(7):476–80.

Jacobs EA, Diamond LC, Stevak L. The importance of teaching clinicians when and how to work with interpreters. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):149–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.001.

Doumouras A, Rush R, Campbell A, Taylor D. Peer-assisted bedside teaching rounds. Clin Teach. 2015;12(3):197–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12296.

Granger CL, Smart A, Donald K, et al. Students experienced near peer-led simulation in physiotherapy education as valuable and engaging: a mixed methods study. J Physiother. 2024;70(1):40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2023.11.006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KT and NJ, first authors, led the project’s conceptualization, investigation, and led the writing of the original draft, review, and editing, including the formal analysis and manuscript preparation, review, and editing. ALV participated in manuscript draft preparation, review, and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The California University of Science and Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study on (protocol # HS-2022-09). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants and/or their legal guardian(s) involved in the study.

Informed consent

All participants involved in this study provided informed consent prior to their inclusion. For participants under the age of 18, informed consent was obtained from their parent or legal guardian.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, K., Jacobs, N. & Lopez Vera, A. A proposal to teach medical students how to use interpreters. Discov Educ 3, 80 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00177-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00177-9