Abstract

Meeting the needs of dual-career academic couples has become an important part of university efforts to foster family-friendly workplaces. Many universities have developed formal or informal approaches to addressing dual-career issues, but variation across institutions has made it difficult to detect wider patterns or probe their implications. In this paper, we analyze the dual-career policies and materials (848 documents total) of all R1 institutions in the United States. As with studies from roughly two decades ago, we find deficiencies in institutional support and transparency. However, given reduced state revenues for institutions of higher education and a rise in precarious employment arrangements over the same time period, conditions for academic couples are arguably worse today. In order for universities to address these concerns and contribute meaningfully to broader forms of inclusion, we argue that there is a need for sustained funding commitments and infrastructural support for dual-career programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Institutions of higher education have been striving to establish more diverse, inclusive, and family-friendly environments [1, 2]. These efforts can manifest in mentorship programs, wellness and appreciation activities, flexible work and family leave policies, or accommodations for academic partners, among others. Although such workplace interventions could improve the lives of faculty, which is a strong rationale for embracing them, they may also increase the productivity of faculty and their allegiance to their institutions [3,4,5]. From this perspective, there are clear instrumental reasons for colleges and universities to move in these directions, not the least of which is becoming more competitive among their peers. However, institutional policies and cultures are typically very slow to change. Moreover, organizations differ radically from one another, making it difficult to spot global patterns of institutional change or discern their meaning for work experiences in higher education more generally.

In this paper, we focus on one dimension of these larger changes in academic life: institutional mechanisms to support academic couples (i.e., dual-career academics). Dual-career academics represent a significant portion of the academic workforce. According to one study conducted from 2006–2007, 36% of university-based full-time faculty researchers were partnered with other academics at the time of the study [6]. This percentage is likely much higher if trained and credentialed academics serving as adjuncts, lecturers, visiting professors, or staff are taken into account. Indeed, the adjunctification of faculty has accelerated in the intervening years such that now more than 70% of instructor positions in higher education are “fixed-term” or contingent [7]. The increasing precarity of academics exacerbates existing challenges of academic couples trying to secure meaningful positions together, potentially making long-term planning difficult [8, 9], generating conflicts within relationships [10], and fostering animosity toward unsupportive universities [11].

To examine universities’ approaches to dual-career academics, we systematically collected and analyzed the dual-career policies and related materials of all R1 institutions in the United States. By investigating dual-career policies and materials, we shed a light on some of the efforts by universities to support faculty holistically, not as atomized agents but as people embedded in meaningful relationships and networks within—and beyond—the workplace. Based on our review of these materials, we argue that if dual-career efforts are to align with the progressive aspirations of academics and meaningfully shift institutional cultures toward broader forms of inclusion, there is a need for sustained funding commitments and appropriate infrastructural support for these programs.

2 Literature review

Scholars have been studying the challenges faced by dual-career academic couples for decades. Some of the earliest work foregrounded individual experiences and obstacles (e.g., [12]), which is an important trend in the literature that has continued (e.g., [13, 14]). Recent work also directs attention to institutional policies, practices, and climate, along with the ways that those elements affect couples’ relationships. With respect to policies, two major studies have drawn attention to the problems associated with a lack of written dual-career policies at academic institutions. The first study, The Two-Body Problem: Dual-Career-Couple Hiring Practices in Higher Education, published in 2003, found that only 45% of research-intensive institutions had dual-career hiring policies [9]. Moreover, of the institutions that did have policies, the majority of those were unwritten or informal [9]. The second study was an authoritative report published by Stanford’s Clayman Institute for Gender Research in 2008. This study affirmed that the majority of universities did not have formal written dual-career policies, which the authors explained was a condition that led to improvised approaches to partner hiring [6]. Such ad hoc approaches can amplify conditions of uncertainty for job candidates in ways that especially disadvantage women who, as Morton [15: 748] finds, are “less likely than men to initiate negotiations regarding their dual-career status,” particularly in the absence of formal policies. Additionally, the Stanford report noted that more than 65% of faculty were unaware of whether their universities had dual-career policies [6]. Thus, even when institutions endeavor to support academic couples, they may be doing a poor job of communicating their positions, which, in turn, may impede related changes in organizational practices and climate.

Research on university practices reveals how cultural biases and assumptions infuse hiring and evaluation processes, including those affecting dual-career couples. For instance, Rivera [16] found that “relationship status discrimination” plays out in hiring decisions such that search committees discriminate against heterosexual women candidates in dual-career relationships if they have partners in current academic positions. The literature also suggests that such discrimination is experienced by LGBTQ+ couples, perhaps especially at religious institutions or those in conservative regions of the United States [6, 17]. Moreover, some of the stigmatizing language used both by institutions and individual faculty members to describe partner hires, such as “trailing partner” or “two-body problem,” can also contribute to the devaluation of their work [6, 18, 19]. In other words, even if dual-career hiring is successful, oftentimes the professional legitimacy of the secondary hire, especially when that hire is a woman, is called into question [20]. These findings illustrate the potency of institutional cultures in shaping an inclusive—or exclusionary—climate for partner hires, irrespective of formal policies or protocols.

The literature also flags how university climates impact dual-career experiences and outcomes. The ongoing evisceration of the tenure system within what has been called the “neoliberal university” [21] can generate apprehension among departments about partner-hire arrangements when faculty view tenure-stream positions as increasingly scarce and precious. In such situations, departments tend to react conservatively to avoid perceived “opportunity costs,” where accepting a partner hire could limit their future hiring allocations [19, 22]. The university climate can also be hostile to partner hires when it has a history of failing to accommodate partners; in these circumstances, faculty who were not able to secure positions for their partners may be, somewhat counterintuitively, unsupportive of positions being made for others [9].

A final thread of the literature reflects on how patriarchal cultures shape couples’ experiences in ways that have implications both for their professional and personal lives. For instance, some studies suggest that flexible work environments, if they exist, tend to benefit men’s productivity but do not have a measurable effect on women’s [23]. Similarly, “female dual-career academics, no matter whether they rate their career as primary or secondary to that of their partner’s career, are more likely to experience negative career consequences [e.g., with respect to appointments, promotions, or career goals]” [5: 780-781]. When academic couples make career decisions, women have a greater probability of declining job offers or leaving their current jobs if their partners do not find acceptable positions [24]. Furthermore, “women are more likely than men to defer to their partners” when both are on the academic job market [25]. Given the dearth of tenure-stream positions, many couples now engage in commuting relationships [13, 26], which may have the unexpected result of couples achieving a form of work-life balance by embracing a “hyper-separation” of their professional lives and personal relationships [14]. At the same time, though, women in heterosexual relationships are more likely to encounter difficulties with commuting relationships as they face role conflicts between their professional and personal identities, especially if they are also mothers [27, see also 28]. On top of all this, as might be anticipated, women academics in heterosexual relationships—whether living with or apart from their partners—undertake significantly more family and household work, which can slow their academic productivity and careers [29, 30].

We contribute to this knowledge base about dual-career academics by exploring the many dual-career materials produced by universities. We ask: How do institutions represent dual-career issues? What steps do institutions take to respond to them? What constraints do institutions face in attempting to implement or maintain dual-career programs? While the dual-career materials produced by universities may have practical uses for administrators, faculty members, or jobseekers, these materials also provide insight into how institutions of higher education conceptualize dual-career issues and dual-career scholars.

3 Methods

In order to investigate the broader dual-career landscape in higher education, we conducted a content analysis [31] of the many heterogenous materials produced by universities as they contend with partner-hire issues. Because women, racialized minorities, and LGBTQ+ scholars continue to be underrepresented in STEM fields [32,33,34], we focused on R1 institutions in particular to concentrate on sites that are most likely to have research-intensive STEM departments and schools [35]. Additionally, R1 institutions have received the majority of National Science Foundation (NSF) ADVANCE grants, which are designed “to increase the representation and advancement of women in academic science and engineering careers” [36], and which have been frequently directed toward the implementation of dual-career programs [37].

Our process of collecting documents pertaining to dual-career hiring at all 146 R1 universities in the United States started with Google searches using each university’s name and the search terms “dual hire policy,” “dual career policy,” “partner hire policy,” and “spousal hire policy.” For each university, all search results appearing to have some connection to partner hiring were followed. After eliminating duplicate search results, each webpage was reviewed to verify its relevancy to dual-career processes or concerns. If it was relevant, the webpage was catalogued on PermaCC to preserve the material in case any websites or links changed. PermaCC is an institutionally provided resource for archiving websites for later public viewing. It generates a permanent repository with persistent links, allowing researchers and others to consult the same documents even if websites go offline or are altered. If the website or document was not capturable through PermaCC, we downloaded it as a PDF. This search yielded 804 unique documents related to dual-career hiring across all R1 institutions. This phase of our data collection lasted from March 16 to June 22, 2022.

To help ensure we were not missing important documents after conducting this web search, we reviewed the collected material to identify contact information for dual-career programs at each R1 university. If no contact information was found, we collected information on university websites for personnel in human resources departments, provosts’ offices, or offices for faculty affairs. We then emailed at least two people (two times each) requesting their universities’ dual-career policies and/or resources. Any information or resources sent that had not been collected in the initial web search, or that had been released since the initial search, was cataloged on PermaCC or downloaded as a PDF. An additional 44 documents were sent, resulting in a total of 848 documents for analysis. This phase of our data collection lasted from January 12 to February 16, 2023.

Two team members then reviewed every dual-career document and performed a content analysis of them. First, team members used an open-coding process to identify themes and subthemes in the policy materials [38, 39]. Second, team members met regularly over the course of 4 months to discuss the themes that emerged from this open-coding process and fine-tune emergent categories. Third, discrepancies were resolved in conversation with the larger project team. Fourth, through an iterative process, team members reorganized and relabeled emerging themes until discrete categories cohered. This process of interpretation resulted in seven thematic categories that are the basis of the present analysis. The goal of this analysis was to focus on qualitative findings, rather than taking a quantitative approach. While measuring the prevalence of themes could provide useful data, the nonstandardized materials collected from the R1 institutions did not lend themselves to counting. Instead, our findings describe the thematic categories and provide an overview of how R1 universities as a whole are managing dual-career issues among their faculty.

The study was reviewed and deemed non-human subjects research by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations as stipulated by this institution’s IRB.

4 Dual-career landscape

Dual-career programs and resources vary considerably across institutions. On one end of the spectrum, there are universities that have well-established programs with dedicated staff members who manage partner-hire cases, liaise between academic units, generate materials for jobseekers and hiring committees, and perform outreach to other employers in the region. These institutions often have designated funding for dual-career hiring and clear policies about how to manage hiring processes. In the middle range, there are many institutions that have some policies or resources but no dedicated personnel or funding commitments. Institutions in this range are sometimes members of a recruitment consortium that provides a tool for jobseekers to search for two available jobs in the respective region. On the far end of the spectrum, a number of institutions have no apparent dual-career programs, policies, or resources. This does not necessarily mean that such universities do not make partner-hire accommodations, but that their mechanisms for doing so—if they exist—are either opaque or ad hoc. Indeed, for many institutions, even those with dedicated dual-career websites and other resources, it was difficult to discern whether and when they actually create faculty positions as part of a partner-hire program. Given this ambiguity, we prioritized categorizing and analyzing what information these institutions do convey about their approach to and valuation of accommodating the needs of dual-career academics. Based on our review of the documents from all R1 universities in the United States, we identified seven key categories for how these institutions approach dual-career hiring: resources, services, eligibility, protocols, funding, sustainability, and framing. Despite variation across institutions, together these categories provide insight into the overall dual-career landscape in higher education today.

4.1 Resources

We found two general types of dual-career resources produced by universities: those for internal audiences and those for external ones. For internal audiences, this could include information provided for department chairs or hiring committees to assist them with understanding the value of partner hires, as well as navigating dual-career issues legally and effectively. For example, Syracuse University set up a webpage for Department Chairs and search committee members to explain the value of accounting for dual-career needs: “Meeting the needs of dual career couples can aid in the recruitment and retention of highly sought after candidates” [40]. Focusing on how institutions might be perceived by potential job applicants, some dual-career resources provided specific language for departments to include for faculty positions, such as Iowa State University’s protocol of stating in ads that there is a dual-career program and that the university is “responsive to the needs of dual career couples” [41]. Other materials aimed to alert search committees to the presence of dual-career programs, including brochures outlining services offered, memos explaining how to request a partner hire, or forms for doing so [42, 43]. There were also training documents for search committee members so they do not ask illegal questions about partner-hire needs but do provide information on the dual-career programs to all job candidates (or finalists for campus visits) whether candidates request such information or not. For example, Drexel University’s protocol states: “Let candidates know that they may ask about dual career issues or other policies that may make Drexel University more attractive to them and that assistance is available” [44]. One way this can occur is to provide job finalists with an opportunity to meet with a neutral party such as a “work-life coordinator” to discuss dual-career or other needs during their campus visits, which is something Oregon State University does [45].

Some internal resources also highlight the importance of integrating a partner hire into one’s department such that they are treated as an equal member. This may be especially relevant for partners placed in non-tenure track positions. For example, recommendations developed at the University of Washington advise Department Chairs to “Introduce the new research professor to the department with as much care as would be given for a regular tenure-track faculty member” [46]. Equal treatment of partners can also serve retention purposes, as materials from the University of Nebraska Lincoln explain: “dual career situations can be an excellent retention opportunity… both partners must be treated individually and equally with other faculty members, with the same care taken toward their retention and evaluation” [47].

Resources for external audiences are primarily geared toward jobseekers. This could include things like a website for the institution’s dual-career program, email addresses for dual-career contacts at the university, or brochures reviewing career-counseling services or information on other employers in the region [48,49,50]. For example, a brochure produced by Virginia Tech informs job candidates:

We want academic and professional couples to know that we support dual career opportunities that allow them to relocate to live and work in our community. The dual career program reflects Virginia Tech’s commitment to enhance the diversity and retention of talented individuals to our university and community. [51]

Another common resource that universities offer for jobseekers is a link to the Higher Education Recruitment Consortium (HERC), which runs a platform allowing individuals to search for jobs, receive job alerts, save job ads, upload their CVs, and apply for jobs. HERC’s search function allows one to specify job types and distances between jobs to “Find two jobs within a commutable distance” [52]. Although institutions that are HERC members often direct jobseekers to this resource, many of those institutions offer no other dual-career services, and, it should be noted, jobseekers could use the HERC platform freely on their own.

4.2 Services

The category of “services” encapsulates the many forms of assistance offered by staff in dual-career programs or aligned units (e.g., Human Resources, Academic Affairs) or by their counterparts at private companies contracted by the university. If an institution has a dual-career program with assigned staff to run it, they may review an academic partner’s materials, meet with them virtually or in person to assess their goals and desired positions on campus, obtain preliminary funding approval for the potential hire, and liaise with all the parties involved to ensure a timely and smooth interview and hiring process [53,54,55]. Tufts University’s webpage describes how

The [dual-career] counselor will meet with the couple to help determine an individualized plan that can best achieve their goals. … As a part of the individualized plan that dual-career counseling offers, there is an opportunity to be connected with a Talent Acquisition team member in order to explore potential on-campus employment opportunities. [54]

Dual-career staff may also periodically visit academic units to remind them of the services their programs offer and the correct processes for pursuing partner hires. It is important to note that most of the documents we reviewed explicitly state that there are no guarantees or obligations for the creation of jobs for academic partners. For example, University of California, Los Angeles tactfully explains,

While it is not possible to guarantee job placement for faculty partners, UCLA wants to ensure that the overall value to the campus of dual career hires is recognized, available resources are deployed, and campus units work together to achieve institutional goals. [56]

In this way, when these dual-career services are present, they are primarily geared toward facilitating straightforward review processes that could lead to successful outcomes.

Another stream of services focuses on career-counseling and -placement assistance for partners, whether for positions at the university or in the surrounding region. These services range from sharing lists of employers in the region, to providing letters of introduction from the university, to offering feedback on job materials, to conducting mock interviews with individuals. In this vein, some institutions, like Purdue University and the University of Chicago, also host training workshops to help partners in “Laying the Groundwork for a Successful Job Search” [57] and “Networking: Get That Ball Rolling!” [58], among others. The emphasis is on helping individuals obtain non-academic positions, although some of the programs we reviewed also make these services available for academic positions. Additionally, these services are usually time-limited, with many being made available for only 1 year, which is a limitation that may particularly disadvantage partners seeking scarce and competitive faculty positions, which may take multiple years to acquire.

4.3 Eligibility

We found that many institutions had restricted eligibility criteria for partners to be considered for university positions or for them to utilize dual-career services. Many universities state that the person being considered for an academic partner-hire position should meet the hiring priorities of the respective academic unit or that they should meet the quality standards expected of regular hires. Ohio State University, for example, notes: “The university does not expect any department/college to hire candidates that do not meet the same quality standards as candidates hired in the receiving department” [59]. Some institutions suggest that the partner hire should be in a position to provide a return on investment for the university in the form of external funding or other resources. Along these lines, Florida International University includes a “Return on Investment” table for departments to complete when making dual-career requests [60].

With respect to which initial hires could avail themselves of dual-career requests, eligibility criteria varied across institutions, with some being much more expansive than others. For instance, Auburn University stresses inclusivity, stating in their guidelines that “any spouse/partner of a newly hired permanent faculty or staff member who is being employed by the university is eligible for these services” [61]. Other universities lean toward partners of tenured faculty only, as with Washington University in St. Louis [62], or with tenure-stream faculty, as with the University of Chicago [58]: “priority for these services is given to the partners of tenure-track and tenured faculty members.” Finally, while many institutions explicitly state that dual-career programs are inclusive of opposite-sex and same-sex couples, some of them simply used the term “spouse” or “partner,” making it unclear how inclusive the programs are in practice.

Eligibility can also be pegged to timeframe. As mentioned above, some dual-career services can be drawn upon only for a short period of time, such as 1 year. At a few institutions, however, we found efforts to expand timeframes for eligibility. For instance, Louisiana State University launched a pilot program to make their new dual-career program available to previously hired faculty so that there would be a degree of equity among faculty with respect to the program [63]. Other institutions, like University of Michigan, allow their program to account for life changes (e.g., acquiring a new partner) so that, if needed, faculty have the opportunity to utilize dual-career services multiple times throughout their careers (Personal communication, 3/13/23).

On the whole, though, many institutions were ambiguous about their eligibility criteria, which might be intentional and strategic on their part, but it could also fuel uncertainty about dual-career offerings and diminish use of them.

4.4 Protocols

Universities have adopted many different protocols for managing dual-career hires. Once a partner-hire request is initiated, the protocols assist in determining the type of position to be pursued, obtaining approvals and funding commitments, interviewing and negotiating with partners, and many other elements in between. Together, these protocols can support institutions in their hiring efforts while also working to meet the needs of dual-career couples. The protocols can allow institutions to tailor programs and processes to their culture and climate while eschewing ad hoc approaches that might lend themselves to bias. For instance, a few institutions with detailed protocols to manage the logistics of partner hires admonish university actors not to overstep their authority by becoming advocates for specific partner hires. Along these lines, Washington University in St. Louis has a special statement saying, “We respectfully ask that colleagues in any university-level offices not serve as an advocate for any individual cases. Such advocacy tends to lead to actions that disregard our established process, causing confusion and risking inequities in our work on retentions.” Statements like this suggest previous events where such confusion did arise, pointing to the need for protocols to prevent similar situations in the future.

Logistically, once a dual-career request comes to the attention of a department, a number of universities provide an explicit workflow delineating how to obtain funding approvals and from whom (e.g., the Provost’s Office), how to coordinate with other academic units, how to initiate a request for an open-search waiver, the criteria that other academic units should use in vetting the partner, and what the funding arrangements should be for the partner hire. (We explore different funding arrangements in more detail below.) For example, many universities are clear that departments should have the opportunity to determine for themselves whether a candidate’s partner would be a good fit rather than being forced by higher administration to accept the hire. This is the case with Georgetown University’s dual-career protocol, which states,

The dean… asks the relevant unit/department within their school to conduct a straw vote to determine if there is interest in hiring the secondary faculty member, and following the outlined process. Only if the vote is positive, the process moves to the next step. [64]

Some institutions also have instructions pertaining to salary decisions for partner hires, such as Georgia Institute of Technology’s rule that the salary “should be commensurate with similar positions in the hiring department” [65]. When universities have dual-career programs, they can manage most of the elements outlined in their protocols, but in the absence of such programs, many universities have a series of forms and memoranda of understanding (MOUs) to guide administrators through the process.

While the positions that partner hires might receive at a college or university depend on many factors, most institutions’ documents are ambiguous about whether a partner could be considered for tenure-track, fixed-term (non-tenure-stream), or staff positions. Of those that do provide more detail, many emphasize fixed-term positions as favored ways of accommodating academic partners. In some instances, partner placement in these positions is justified in budgetary terms. For example, Michigan State University states, “For financial reasons and due to qualifications, most spousal/partner hires are accommodated with non-tenure stream faculty or academic staff positions” [66]. There were also many contingency arrangements outlined, such as slotting partners into “teaching assistant professor” positions that might serve as bridging positions to tenure-stream options when they became available at a later date. Some non-tenure-track positions, while technically fixed term, have more potential as long-term employment; whereas others are designed to be short term. Some institutions offer positions intended to be temporary. For instance, documentation from the University of Pittsburgh states: “For the majority of partner hires, academic opportunities for the partner should be developed primarily as visiting professorships… and as fellowships… These appointments should normally be for no longer than 3 years” [67]. Some of these contingency arrangements may be beneficial for universities but less convincingly so for individuals, such as Old Dominion University’s option that partners could become “unpaid research faculty” who could apply for grants and contracts, from which the university would undoubtedly collect facilities and administrative (i.e., indirect) costs [68].

After partner hires are made, there are additional concerns that university protocols help address. Because fears of losing out on later hiring opportunities are a powerful deterrent to departments considering partner hires [19], some institutions outline when and under what circumstances those opportunity costs will apply. For example, Michigan State University stipulates that the partner hire will count against a department if that is where the primary hire is being made, but it will not count against a department if the primary hire is being made elsewhere [66]. Then, especially for universities with dual-career programs, there may also be a final stage of program evaluation and assessment, where staff collect and analyze data on the demographics of who was served by dual-career services, whether they were hired or retained successfully and into which positions, whether they went elsewhere instead and where that was, and so on (Personal communication, 2/17/23). By having protocols in place to process these data, dual-career offices may be able to document the importance and success of their efforts and to leverage support for their continuation.

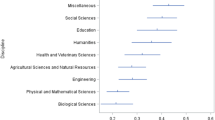

Although it is not the objective of this paper to provide detailed comparisons of institutions, there were notable differences across institution locations and types with respect to protocols. More institutions in the Midwest had evidence of facilitating faculty positions for partner hires, with 73% clearly doing so, compared to only 40% of institutions in the Northeast. Similarly, more public institutions supported these actions (73%) than private institutions (36%), at least based on what the available documents show.

4.5 Funding

Financial support is crucial to the success of dual-career hiring [6], so it was not surprising that many places that address dual-career issues outline their specific funding arrangements. The most common approach to paying a partner’s salary was a 1/3-1/3-1/3 model, where the costs are split evenly between the department making the primary hire, the department making the partner hire, and the Provost’s Office. Typically, institutions specify a time limit of 3 years for this arrangement to be in effect, after which the department making the partner hire absorbs the full cost of that person’s salary. However, for some institutions, such as the University of Michigan, if the partner hire is untenured, the original funding commitments remain in effect until that person receives tenure even if that takes more than 3 years (Personal communication, 3/13/23). There were also institutions, such as Iowa State University, that have provisions for stripping Provost support for a partner hire if the primary hire leaves the institution for any reason [69].

Another funding dimension concerns the total amount available each year for partner hires at an institution. Although we found very few references to specific dollar amounts or institutional-level formulas, the references we did find offer a sense of what these financial commitments might look like. Florida International University, for instance, allocates $200,000 per year [60]. Some universities in the Midwest and in rural settings have more ambitious funding commitments. For instance, the College of Arts and Letters at Michigan State University claims that “for every three hires each year, the College sets aside funding in its budget for one spousal/partner hire” [66]. When it comes to processes for accessing the funds, some institutions, such as Ohio State University, assert that funds will be granted on a “first come first served basis” [70], which is a provision that could give hiring departments some assurance that administrative preferences or favoritism do not play a role in such decisions. We also found evidence of partner-hire funding disappearing, such as the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, relating that “as of May 10, 2022, the Provost's Office is no longer providing financial support for partner hires” [71].

Finally, start-up funds for research can present a special challenge for making successful dual-career hires. Particularly for scholars in the STEM fields, where access to lab spaces could be essential for launching and maintaining one’s career, this funding component is both necessary and costly. Nonetheless, as with other funding elements, many universities do not delve into the particulars of start-up or research funds. One notable exception was another Midwestern school, Purdue University, whose documents state that the Provost’s Office will cover fifty-percent of a partner’s start-up costs up to $200,000 [72].

4.6 Sustainability

Our review of dual-career materials also revealed a discernable pattern of many partially launched dual-career initiatives that had, as far as we could tell, since faded away. We discovered a trove of previous taskforce minutes, faculty senate motions, Provost memos to the faculty, and press releases about pilot programs, yet many places with these materials also had dead web links to such programs and no evidence of their current existence. Rutgers University–New Brunswick offers a case in point, where its university senate endorsed the creation of a robust Dual Career Services program in 2013 [73], which was met with a letter from the university president in 2014 postponing a decision until after a one-year pilot program had elapsed [74], after which there is no evidence of any dual-career programs or policies being implemented. Oftentimes, the institutions that had previous—but no current—evidence of engagement with dual-career issues were those that had received funding through NSF’s ADVANCE program. Therefore, funding from NSF may catalyze dual-career initiatives at some universities, but our findings suggest that without continued financial and political support from those academic institutions, the sustainability of such initiatives is at risk once the grants conclude.

4.7 Framing

The final category in our assessment of R1 institutions’ dual-career materials is that of “framing,” which encompasses the rationales for making partner hires, the language used to discuss them, and the images used to represent them. Across these areas, the tone of the materials serves a rhetorical function of communicating an institutional position on the issues. For instance, some universities convey a sense of general suspicion of scholars who request partner hires, as seen with universities, such as Florida International University, demanding proof of eligibility through the presentation of a marriage license or an affidavit of same-sex partnership [60]. Through their language choices, other institutions perhaps unwittingly communicate that dual-career hiring is a nuisance, for instance by referring to it as “the two-body problem” or by using the stigmatizing term of “trailing partner” [6, 19]. For example, a policy at the University of Buffalo relates: “Trailing spouses may seek consideration for an academic appointment or a position in the University Administration” [75]. By contrast, most documents we reviewed position dual-career hiring as a welcome “opportunity” akin to other target-of-opportunity or diversity hires. It is possible, if not likely, that the individuals drafting many dual-career materials were anticipating an apprehensive university audience and striving to shift its thinking about dual-career hiring. For example, in its recommendations to Chairs at the University of Washington, the dual-career program team enjoins readers to “view hiring a dual career couple as a great way to retain both faculty members. (It’s not a bug, it’s a feature!)” [46]. Similarly, documents, such as those at Iowa State University, underscore how partner hiring is a key mechanism for “recruiting and retaining the highest quality faculty” at universities [76].

There is also a trend in institutions representing dual-career couples through images, particularly in their brochures and websites for dual-career programs. Although these media sometimes contain text only, when individuals are depicted, they frequently include mixed-race and same-sex couples. For instance, a brochure for Johns Hopkins University’s dual-career services includes an image of two sporty white men standing close together in one frame and a smiling and laughing mixed-race couple with two children in an adjacent frame [77]. Next to these two images is an offset quote reading, “JHU’s Dual Career Services program gave us confidence that we would be able to pursue our chosen professions together in an amazing environment” [77]. Representations of children are frequent among these media, and documents occasionally include images of older couples as well. Although these brochures and websites clearly operate as public-relations and recruitment materials that communicate inclusiveness, we also found they contribute to the overall framing of dual-career hiring and its fit within specific institutions. Indeed, these materials perform institutional aspirations for the role of dual-career hiring in achieving universities’ broader diversity goals.

5 Conclusion

There are admirable efforts underway to transform universities into workplaces that are more diverse, inclusive, and family friendly. Dual-career programs offer one approach to treating faculty members in a holistic way, as individuals who exist within larger webs of obligation that extend beyond the university and from which the university can also benefit. Although the presence of dual-career policies and programs can be read as institutions’ recognition of the importance of these issues, some of our findings were less encouraging. Indeed, our review of dual-career materials underscores the variability and complexity of initiatives currently underway at R1 institutions, with some dedicating staff and funding to the programs, some outsourcing to career-services agencies or HERC, and some approaching dual-career needs with suspicion. Just as the earlier research reports (The Two Body Problem and the Stanford study) from roughly two decades ago found a lack of institutional support and transparency with respect to academic couples [6, 9], our study shows how, in many ways, these problems persist. Moreover, given reduced state revenues for institutions of higher education and an increase in precarious employment arrangements over the same time period [21, 78, 79], the conditions for academic couples are arguably worse today. This is the case even with some important shifts in university cultures, such as the examples we reviewed of supportive language surrounding dual-career hiring.

By organizing our findings into seven categories— resources, services, eligibility, protocols, funding, sustainability, and framing—we offer a snapshot of the current institutional landscape for dual-career issues. This snapshot also provides a window onto institutional identity and culture, wherein the materials we collected are forms of discourse through which universities shape themselves. How institutions define problems and wrestle with solutions betray their own conception of larger changes and their role or aspirational position within them. This does not mean that institutions speak univocally in ways that are divorced from their members; rather, organizations are constituted through the diverse communicative acts of their members [80, 81], including formal policies and protocols that shape individuals’ experiences of those institutions. More broadly, the current dual-career landscape is reflective of the gestalt changes underway in the academy, revealing important patterns of institutional constraint, competition, and interdependency.

In this vein, the heterogenous approaches to dual-career issues we found are no doubt reflective of the unique institutional histories and cultures within which they emerge. Budgetary constraints and job scarcity—real or fabricated—are factors in how colleges and universities respond to partner-hire needs, but arguably even more important are the perceptions of administrators and faculty of the benefits and risks of partner hiring. The fact that many dual-career arrangements are temporary, such as with fixed-term (non-tenure-stream) positions or with time-limited career-services support, can be seen as a reflection of the neoliberalization of universities and the evisceration of the tenure system [21]. But it also suggests that many universities are not as invested in partner hiring as they could be. By postponing a complete engagement with dual-career needs through such temporary positions or services, universities may risk aggravating the uncertainty and stress of partnered faculty, who, in turn, may be less inclined to remain at those institutions [17]. In addition, by favoring fixed-term positions as the primary way of accommodating academic partners, such as was the case with Michigan State University and the University of Pittsburgh, institutions effectively treat those scholars as unequal to the primary hire. This reveals a tension in our data between the use of inclusive language in dual-career documents and the privileging of precarious positions for appointments. Such fixed-term positions potentially sabotage partners’ careers if they remain in them too long [82, 83]. Drawing on the academic literature, it is evident that patriarchal norms shape these outcomes as well, with women in heterosexual relationships being more likely to be slotted into fixed-term positions or face career interruptions [24, 84]. Thus, partner hiring into temporary or lower-status jobs may enable couples to be at the same institution, but there might be long-term costs to the partner’s career when placed in those positions. These potential costs are especially important when considering the biases that women already face in academia, which universities may be reinforcing through restrictive partner hire policies [16, 85].

Dual-career materials are also discursive performances through which institutions produce their identities and assert their values, where they express their insecurities and sketch their goals. From this vantage point, it is not surprising that an undercurrent of competition flowed throughout these materials, particularly with respect to attracting and retaining leading scholars. Almost three-quarters of Midwest institutions, for instance, offered evidence that they created faculty positions for partner hires compared to fewer than half of the institutions in the Northeast. In this way, partner hiring may be seen as an important mechanism for recruiting top academic talent, providing a way to compete with institutions that might have other advantages, such as perceived geographic desirability or greater prestige.

Although the wider culture may be shifting to recognize the importance of addressing dual-career needs in academia, institutional supports are key to harnessing the potential of that change. The apparent dwindling of some dual-career programs over time shows that both funding commitments and sustained personnel involvement are likely necessary for such programs to flourish. As with many university initiatives, though, the mere presence of dual-career programs does not ensure their success, for they also must be integrated effectively into hiring and retention processes, be adopted by administrators and faculty members who may initially feel constrained or threatened by them, and achieve sustainability so that they can become a dependable resource for others. In short, dual-career programs must achieve a deep form of institutionalization that requires funding commitments, time, and a robust social infrastructure to support them. Part of that social infrastructure is populated by the personnel who are behind the production and administration of dual-career programs, but it also includes the many documents and materials that give shape to those programs and facilitate their functioning. Our review of this material indicates that despite the progress being made, most R1 institutions have more work to do to address fully the needs of academic couples.

Data availability

All the data analyzed are included in this published article. Perma.cc links to full-text documents are also provided in the References.

Change history

30 April 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00127-5

References

Iverson SV. Camouflaging power and privilege: a critical race analysis of university diversity policies. Educ Adm Q. 2007;43(5):586–611.

Sallee MW. Gender norms and institutional culture: the family-friendly versus the father-friendly university. J Higher Educ. 2013;84(3):363–96.

Welch JL, Wiehe SE, Palmer-Smith V, Dankoski ME. Flexibility in faculty work-life policies at medical schools in the Big Ten conference. J Womens Health. 2011;20(5):725–32.

Woolstenhulme JL, Cowan BW, McCluskey JJ, Byington TC. Evaluating the two-body problem: measuring joint hire productivity within a university (Working Paper), 2012. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.646.7766&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Zhang H, Kmec JA. Non-normative connections between work and family: the gendered career consequences of being a dual-career academic. Sociol Perspect. 2018;61(5):766–86.

Schiebinger L, Henderson AD, Gilmartin SK. Dual-career academic couples: what universities need to know. Stanford: Michelle R. Clayman institute for gender research, Stanford University; 2008.

AAUP. Background Facts on Contingent Faculty Positions. https://www.aaup.org/issues/contingency/background-facts

Sotirin P, Goltz SM. Academic dual career as a lifeworld orientation: a phenomenological inquiry. Rev High Educ. 2019;42(3):1207–32.

Wolf-Wendel L, Twombly SB, Rice S. The two-body problem: dual-career couple hiring policies in higher education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2003.

Isaac KD. Dual-career couples: a coup or to cope in academia. Columbus: EdD, Education, Columbus State University; 2018.

Purcell M. “Skilled, cheap, and desperate”: non-tenure-track faculty and the delusion of meritocracy. Antipode. 2007;39(1):121–43.

Alder PA, Adler P, Ahrons CR, Perlmutter MS, Staples WG, Warren CAB. Dual-careerism and the conjoint-career couple. Am Sociol. 1989;20:207–26.

Larson SJ, Miller A, Drury I. Reflections on tenure, the two-body problem, and retention in the 21st century academy. J Public Aff Educ. 2020;26(4):506–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2020.1759346

Sallee MW, Lewis DV. Hyper-separation as a tool for work/life balance: commuting in academia. J Public Aff Educ. 2020;26(4):484–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2020.1759321

Morton S. Understanding gendered negotiations in the academic dual-career hiring process. Sociol Perspect. 2018;61(5):748–65.

Rivera LA. When two bodies are (not) a problem: gender and relationship status discrimination in academic hiring. Am Sociol Rev. 2017;82(6):1111–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417739294

Blake DJ. Dual-career hiring for faculty diversity: insights from diverse academic couples. Samuel DeWitt Proctor Institute for Leadership, Equity, and Justice, 2020.

Careless EJ, Mizzi RC. Reconstructing careers, shifting realities: understanding the difficulties facing trailing spouses in higher education. Can J Educ Adm Policy. 2015;166:1–28.

Monahan T, Fisher JA. Partnering through it: confronting the institutional challenges facing dual-career academic couples. J Women Minor Sci Eng. 2023;29(3):87–101.

Culpepper D. They were surprised: professional legitimacy, social bias, and dual-career academic couples. J Divers High Educ. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000454

Kezar A, DePaola T, Scott DT. The gig academy: mapping labor in the neoliberal university. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2019.

S. Kurniawan. UC Santa Cruz Faculty Community Networking Program 2018–2019: women faculty in STEM [Report]. 2019.

Feeney MK, Bernal M, Bowman L. Enabling work? Family-friendly policies and academic productivity for men and women scientists. Sci Public Policy. 2014;41(6):750–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scu006

Zhang H, Kmec JA, Byington T. Gendered career decisions in the academy: job refusal and job departure intentions among academic dual-career couples. Rev High Educ. 2019;42(4):1723–54. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0081

Mason MA, Goulden M, Frasch K. Why graduate students reject the fast track. AAUP. 2009;95:11–6.

Lindemann D. Commuter spouses: new families in a changing world. Ithaca: ILR Press; 2019.

Sallee MW. A temporary solution to the two-body problem: how gender norms disadvantage women in commuting couples. J Divers High Educ. 2023;16(2):170–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000334

Fox MF, Fonseca C, Bao J. Work and family conflict in academic science: patterns and predictors among women and men in research universities. Soc Stud Sci. 2011;41(5):715–35.

Schiebinger L, Gilmartin SK. Housework is an academic issue. Academe. 2010;96:39–44.

Ward K, Wolf-Wendel L. Mothering and professing: critical choices and the academic career. NASPA J Women High Educ. 2017;10(3):229–44.

Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2004.

Pascale AB. Supports and pushes: insight into the problem of retention of STEM women faculty. NASPA J Women High Educ. 2018;11(3):247–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407882.2018.1423999

Freeman JB. Measuring and resolving LGBTQ disparities in STEM. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci. 2020;7(2):141–8.

Carter DF, RazoDueñas JE, Mendoza R. Critical examination of the role of STEM in propagating and maintaining race and gender disparities. In: Paulsen MB, Perna LW, editors. Higher education: handbook of theory and research, vol. 34. Cham: Springer; 2019. p. 39–97.

Carnegie Classifications. (2020) Carnegie classification of institutions of higher education. https://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/

National Science Foundation. ADVANCE at a glance. https://www.nsf.gov/crssprgm/advance/

McMahon MR, Mora MT, Qubbaj AR, editors. Advancing women in academic STEM fields through dual career policies and practices. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing; 2018.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2006.

Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998.

Syracuse University. Department chairs and search committee members. 2022. https://perma.cc/4Y9R-P2AJ

Iowa State University. Iowa State University job ad. 2022. https://perma.cc/94DU-NMPD

George Mason University. Waivers from recruitment search for faculty. 2022. https://perma.cc/ZVC3-4Y2F

Ohio State University. Dual career hiring cost-sharing fund request. 2022. https://perma.cc/A2KX-U7HZ

Drexel University. Handbook for faculty recruitment. 2023. https://studylib.net/doc/10442533/

Oregon State University. Creating a family-friendly department: toolkit for academic administrators. 2022. https://perma.cc/BU9S-V63P

University of Washington. Recommendations to chairs for facilitating dual career hires. 2022. https://perma.cc/8XEF-LY2L

University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Best practices: faculty recruitment, development and retention. 2012. https://perma.cc/2VBL-E8X3

University of Delaware. Dual career services. 2022. https://perma.cc/T7AH-H9FN

University of Georgia. Dual career assistance program (DCAP). 2022. https://perma.cc/HXM4-6JN3

University of Notre Dame. University of Notre Dame dual career assistance program. 2022. https://perma.cc/2LEQ-Q8FA

Virginia Tech. Dual career program. 2022. https://perma.cc/GS8D-SE2T

Higher education recruitment consortium. HERC Jobs. 2023. https://perma.cc/S732-ZMX2

University of Chicago. Dual careers & faculty relocation. 2022. https://perma.cc/P4DH-R287

Tufts University. Dual career and relocation resources. 2023. https://perma.cc/5XU2-XVKH

Texas A&M University. (2022) dual career. https://facultyaffairs.tamu.edu/Opportunities/Dual-Career

UCLA. Dual careers at UCLA. 2022. https://perma.cc/Y4FX-Q7QJ

University of Chicago. Training resources. 2022. https://perma.cc/RA6R-Q8MF

University of Chicago. Workshop series. 2022. https://perma.cc/ME8C-8H5A

Ohio State University. Office of academic affairs, policies and procedures handbook: Volume 1. 2022. https://perma.cc/XP55-J6S9

Florida International University. Dual career academic hire program. 2022. https://perma.cc/96Y5-53A4

Auburn University. Guidelines for dual career services. 2022. https://perma.cc/SSK7-XSGF

Washington University in St. Louis. Arts & Sciences statement on dual career and domestic partner/spouse recruitment. 2022. https://perma.cc/SY8A-88Z2

Burkes C. Academic Affairs launches program for equity in spousal hiring. Reveille. 2015. https://perma.cc/PSY7-YYJ4

Georgetown University. Dual-career recruitment and retention for faculty. 2021. https://georgetown.app.box.com/s/3jgngfa3xi6l0xkfcbdhw4359a13ztaw

Bras RL. Funding guidelines for dual career couple hiring opportunities. 2012. https://perma.cc/DW6K-KTBC

Michigan State University. Spousal/partner hire decision guidelines. 2020. https://perma.cc/J9UF-3SPS

University of Pittsburgh. Dual career recruitment and retention program. 2020. https://perma.cc/WKQ7-EPK2

Old Dominion University. Dual career resource for those hiring full-time faculty. 2017. https://perma.cc/TW6H-CHS5

Iowa State University. Salary support for strategic faculty recruitment and partner opportunity hires. 2022. https://perma.cc/U4U6-D3K5

Ohio State University. Dual career hiring. 2022. https://perma.cc/798M-FJRE

University of Tennessee. Opportunity and spousal/partner hires. 2023. https://perma.cc/NET8-EDQ6

Purdue University. Dual career assistance program. 2021. https://perma.cc/B5B2-S8X8

Rutgers University Senate. Response to charge S-1306: dual career services program. 2013. https://perma.cc/L5CE-EAW6

Barchi RL. Response to report and recommendations on charge S-1306. 2014. https://perma.cc/SBE2-CUHW

Sarlin P, Pack SD, Jadamec M. Dual-career couples and spousal hires: principles and practices. 2018. https://perma.cc/VKP5-YRMJ

Iowa State University. Dual career resources. 2022. https://perma.cc/VF2D-GXKX

Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins dual career services. 2022. https://perma.cc/8KF9-VM6G

Fleming P. Dark academia: how universities die. London: Pluto Press; 2021.

Flannery ME. State funding for higher education still lagging. NEA Today, October 25 2022. https://www.nea.org/nea-today/all-news-articles/state-funding-higher-education-still-lagging.

Ashcraft KL, Kuhn TR, Cooren F. Constitutional amendments: “materializing” organizational communication. Acad Manag Ann. 2009;3(1):1–64.

Mumby DK. Organizing power. Rev Commun. 2015;15(1):19–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2015.1015245.

Allmer T. Precarious, always-on and flexible: a case study of academics as information workers. Eur J Commun. 2018;33(4):381–95.

Finley A. Women as contingent faculty: the glass wall. On Campus with Women. 2009;37(3).

Wolfinger NH, Mason MA, Goulden M. Stay in the game: gender, family formation and alternative trajectories in the academic life course. Soc Forces. 2009;87(3):1591–621.

Blake DJ. Gendered and racialized career sacrifices of women faculty accepting dual-career offers. J Women Gender High Educ. 2022;15(2):113–33.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. SES-2122460. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this article’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by T.M., M.W., and J.A.F. A.P. performed literature review for the article. The first draft of the manuscript was written by T.M., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent

There were no human subjects as part of this study.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been updated to correct the Literature review section.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Monahan, T., Waltz, M., Parker, A. et al. A review of the institutional landscape for dual-career hiring in higher education. Discov Educ 3, 34 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00118-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00118-6