Abstract

Background

Entrepreneurship is seen as the solution to graduate unemployment in Ghana, and students are required to take a course on entrepreneurship that teaches them how to work for themselves. Therefore, this study investigated the psychological precursors of entrepreneurial intentions among higher education students.

Methods

Using the analytical cross-sectional survey design, 250 participants were sampled from public universities to participate in the survey. Participants were required to respond to three constructs (entrepreneurial scaffolding, psychological capital, and entrepreneurial intentions). The data analyses were performed using multivariate regression.

Results

The study’s findings showed that entrepreneurial scaffolding and psychological capital were significant predictors of entrepreneurial intentions.

Conclusion

The researchers concluded that students’ convictions about succeeding or failing and plans to engage in entrepreneurial behaviours depended on proper entrepreneurial guidance and a positive mindset. As a result, higher education institutions and career counsellors in Ghana should be strengthened and include practical guides to entrepreneurial training, thereby reducing graduate unemployment in Ghana.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Statistically, the young population (between 15 and 25 years old) in Africa is around 70% [1]. It is reported that the current population in Africa stands at 1.3 billion, with the projection that it will multiply twice by 2050 [2]. The increase in population shows that the search for jobs by the young will eventually increase over time [2]. The increase in the young population has led to the transformation of labour market analysis in most African countries in recent years [2]. It is acknowledged, however, that traditional measures of employment and unemployment have fallen short of capturing the expanding complexity of today’s labour markets [3, 4]. The International Labour Organization [5] published a report bolstering this claim by reiterating that unemployment statistics fail to accurately reflect the realities faced by young people in the labour market. Young people’s participation in the labour market is essential to recognising a thriving, sustainable, and equitable socioeconomic environment, as noted by the International Labour Organization [5].

Conversely [6, 7], allege that high structural unemployment and underemployment among youth are significant risks facing the global economy. This situation might increase exponentially on the African continent as most higher education institutions continue to graduate young people every academic year without readily available job opportunities. In 2016, Kelvin Balogun, the President of Coca Cola stated that “almost half of the 10 million graduates churned out of the over 668 universities in Africa yearly do not get jobs.” This unemployment phenomenon was attributed to the lack of skill sets needed for these graduates to get absorbed into the job market.

According to the United Nations Resident Coordinator in Kenya, one critical reason that prevents organisations from engaging sub-Saharan African graduates is that they complete their education without possessing the required skills to be involved in any meaningful job opportunity [8]. Unemployment is a problem that is bad for both the graduates and their own African countries. The World Bank’s 2014 report shows that the rising unemployment rate in Africa has forced many young college graduates to turn to crime, become radicalized, and risk their lives to get to Europe in search of good jobs. Unemployment is a political, socioeconomic, and development challenge for any affected nation. Unemployment harms economic growth and development in every nation [9]. While economic growth helps create jobs, more jobs lead to economic growth and development. With no immediate solution to Africa’s unemployment problem, most higher education institutions (HEIs) have resorted to imparting entrepreneurial knowledge to their students in order to best equip them to face the bleak picture of unemployment by engaging in self-motivated entrepreneurial jobs. Wu and Tian [10] say that researchers have started looking into why people start being and acting like entrepreneurs. This is because it is important. The definition of entrepreneurship is the process of seeking out and acting upon opportunities to create novel goods and services; market and production organisation strategies; process and raw material innovations; and other outcomes that may not be immediately obvious [11]. Diandra and Azmy [12] argue that entrepreneurship is a necessary component of thriving businesses, and those who take an active role in it are the ones ultimately responsible for making sure it succeeds.

It is significant to note that intentions frequently have an impact on people’s actions. From a psychological point of view, if “any human being wants to achieve something, there should be an intention for that” [13]. This is synonymous with entrepreneurship, as those engaged in it need to possess an entrepreneurial intention as a foundation. According to Moriano et al. [14], the entrepreneurial intention has been defined as the conscious state of mind that precedes action and directs attention towards a goal such as starting a new business.

Wu and Tian [10] note that numerous scholars have recognised the importance of entrepreneurial intention (EI). Likewise [15, 16], stated that people who engage in entrepreneurial activities are those who possess strong EI. For students in higher education institutions (HEIs) in Africa, the zeal to engage in entrepreneurial behaviours and actions could come from entrepreneurial intentions and the needed actions towards any chosen self-motivated, entrepreneurial entity. The intention of students in HEIs to engage in entrepreneurial actions can be influenced by entrepreneurial scaffolding (ES) from their institutions and their psychological possessions, such as psychological capital (PsyCap).

In Africa, the spike in unemployment rates is unabated. In South Africa, the youth unemployment rate has been a significant challenge. In recent times, the youth unemployment rate has been estimated to be around 32.9% [17, 18]. This high rate of youth unemployment has been a cause for concern in the country, with efforts being made to address the issue through various policy measures such as entrepreneurial ventures. Likewise, Nigeria is another African country grappling with high youth unemployment rates. Currently, the youth unemployment rate in Nigeria is reported to be approximately 41.0% [19, 20]. This figure highlights the ongoing challenges in the labour market and the need for initiatives to enhance youth employment opportunities. Equally, Ghana has also faced youth unemployment challenges. The accumulated youth unemployment rate in Ghana is estimated to be around 12.6% [8, 21]. Despite this relatively lower rate compared to some other African countries, youth unemployment remains a concern, and efforts are being made to create more job opportunities for young people.

1.1 Entrepreneurial scaffolding and entrepreneurial intention

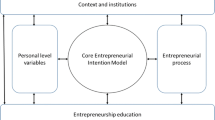

In the field of psychology, scaffolding is a strategy in which professionals in a given field display the process of problem-solving for their students and then explain each step as they go along. After giving a few basic explanations, the teacher will step back and only help when it's needed [22, 23]. Applied in business and entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial scaffolding is the support, training, strategies, and ideas offered to people who want to pursue business to become independent in the job market. The importance of entrepreneurial scaffolding in fostering the development of a business mindset in individuals cannot be overstated. Entrepreneurship scaffolding, as discussed by Nambisan et al. [24] and Scott et al. [25], is seen as a key component in encouraging constructive self-employment practises and the development of entrepreneurial aspirations and confidence. This is due to the fact that the role of entrepreneurial scaffolding is widely regarded as one of the most important factors in generating confident predictions about the potential success of new businesses [25].

In this research, we use the term “entrepreneurial scaffolding” to mean making it easier for entrepreneurs to learn, act, and make money from their ideas. Tarling et al. [26] say that the goal of entrepreneurial education is to make it more likely that a new business will be successful by teaching students about all the different parts of starting and running a business. Literature [27,28,29] shows that entrepreneurship education can help entrepreneurs. Also, Entrialgo and Iglesias [30] says that entrepreneurship education is important because it can help people who want to start their own businesses shape their ideas. It can also make it less likely for new businesses to fail. Literature [31, 32] shows that entrepreneurial scaffolding is important because it helps people discover, re-discover, and build confidence in entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial scaffolding in education and awareness activities helps transform the unfavourable impression of entrepreneurship and helps replace the entrepreneur’s uncertainties [33]. Entrepreneurial scaffolding promotes entrepreneurial intent and spirit, improves knowledge, reduces ambiguity, and boosts confidence [34,35,36]. Higher education institutions play a crucial role in fostering student entrepreneurship and putting it into practice [37, 38] by providing avenues such as education in entrepreneurship, fora and marketing strategies. According to Schwarz et al. [39], entrepreneurial scaffolding fosters an entrepreneurial mindset towards starting a new enterprise.

Empirically, entrepreneurial scaffolding and intention are documented in several studies. For instance, Feranita et al. [40] investigated the role of entrepreneurial education in preparing the next generation of entrepreneurs in Malaysia using 191 undergraduate students. The findings of the study revealed a significant relationship between entrepreneurial scaffolding and both entrepreneurial orientation and intent among Malaysian undergraduate students. Likewise, Yigitbas et al. [41] study revealed a significant positive relationship between entrepreneurial scaffolding and intention among higher education students. Additionally, Wahidmurni et al. [42] researched into impacts of using modules on students’ entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions. The study revealed that entrepreneurial scaffolding was a precursor of entrepreneurial intentions among higher education students.

The literature agrees that an entrepreneur’s education is important because it helps them see how competent new businesses are [25, 43, 44]. Entrepreneurial scaffolding leads to better behaviour and innovative start-up plans [45]. According to Neto et al. [46], students who participated in entrepreneurship classes demonstrated a higher inclination towards entrepreneurship compared to their counterparts. The presence of a well-designed entrepreneurial education curriculum and supportive environment within universities serves as a catalyst for encouraging young individuals to pursue entrepreneurial endeavours [47]. Liguori et al. [48] discovered that many aspiring student entrepreneurs face challenges such as limited market experience and risk aversion, which hinder their readiness to start businesses. Shamsudeen et al. [49] highlighted that entrepreneurial education fosters participants’ creativity and instills a proactive mindset to perceive transitions as opportunities. While colleges and universities employ various strategies to promote entrepreneurship [50], emphasised the importance of measuring their impact on students. The implementation of entrepreneurship scaffolding varies, with some institutions providing general knowledge and skills required for initiating new projects to showcase entrepreneurial capabilities, while others offer targeted resources to individual students or groups to nurture entrepreneurial ventures [51, 52].

Using a pre-test and post-test experimental design, Souitaris et al. [53] investigated how interested and prepared undergraduate students were to be entrepreneurs. The research showed that both the average subjective norm and the average intention to work for oneself were higher for participants after the training than they were before [53]. Despite this, participants’ post-program entrepreneurial intentions bore little resemblance to those of the programme’s rising entrepreneurs. As Souitaris et al. [53] put it, the well-known lag between entrepreneurial intentions and actions may account for the fact that there is no association between entrepreneurial education and intention at the end of the curriculum. Yet, the research showed that students who participate in entrepreneurship training are exposed to “trigger events” that encourage them to take risks and start their own businesses [53].

1.2 Psychological capital (PsyCap) and entrepreneurial intention

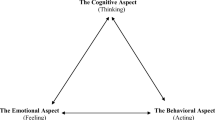

Psychological capital (PsyCap) is an aspect of positive psychology. Positive psychology emerged in the late 1990s, emphasising what is good about people rather than what is wrong [54,55,56]. According to Cameron et al. [57], positive psychology has two channels of manifestation, including the macro-oriented positive organisational scholarship (POS) movement and the micro-oriented state-like positive organisational behaviour (POB) approach. Therefore, psychological capital consists of numerous sub-components of these channels of manifestation in positive psychology. Psychological capital refers to the mental state of a person who demonstrates excellent organisational behaviour and strong job performance [58]. Self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism are all components of PsyCap [59]. According to Lupșa et al. [60], PsycCap involves self-efficacy, hope, optimism, resilience, opportunity recognition, and social ability, which are the six pillars of PsyCap. Personal and professional success, as well as various aspects of one’s behaviour, are all impacted by one’s level of psychological capital. Performance and contentment can be improved with the help of PsyCap, which emphasises power, success, adornment, and happiness [61]. The level of an individual’s psychological capital also plays a role in the way they behave as an entrepreneur. An individual’s success and happiness are reflected in their “psychological capital.” [58, 62,63,64,65] all agree that the existence of such evidence is crucial to the development and success of a business. For starters, PsyCap can affect how easily business owners raise funds and hire new employees [66]. Researchers found that PsyCap (self-efficacy and need for achievement) and an entrepreneurial orientation were strongly linked to a desire to start a business [67].

Several studies have found a positive relationship between PsyCap and EI. For example, EI has been found to be related to all aspects of PsyCap (including self-efficacy and resilience) in previous studies [68, 69]. In some studies, it is found that higher levels of PsyCap, including self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience, have been associated with greater entrepreneurial intentions [70, 71]. Some studies have shown that entrepreneurial self-efficacy mediates the relationship between PsyCap and EI. In other words, PsyCap influences EI through its impact on entrepreneurial self-efficacy [72, 73]. Therefore, it is important to note that the relationship between PsyCap and EI may vary across different cultural contexts. Studies conducted in different countries have revealed both similarities and differences in this relationship, highlighting the importance of considering cultural factors [72, 74, 75]. According to Hmieleski and Carr [76], differences in the success of startups can be attributed in part to the entrepreneurs’ psychological capital. PsyCap was found to be an indirect predictor of entrepreneurial intentions among Chinese college students [66].

1.3 The case of Ghana

According to the World Bank [77], small businesses make up about 85% of all businesses and account for about 70% of Ghana’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020. Regardless of SMEs’ dominance and their contribution to the GDP, they faced several financial and regulatory challenges. For instance, the World Bank [77] report on Doing Business for 2020 indicated that the average cost of starting a business in Ghana is US$125.46, while it only costs US$56.51 and US$32.32 in Togo and Benin, respectively [77,78,79,80]. For those in Rwanda, registering a new business is free, and small businesses are exempt from all fees for a period of 2 years. Among 10 African countries, Ghana has ranked the 7th best country to become an entrepreneurial hub [81]. Despite this, entrepreneurship is seen as one of the major drivers of the economy. According to Bawakyillenuo and Agbelie [82], several Ghanaians consider entrepreneurship to be a good occupational choice. In this regard, the government has made a step by providing financial backing to aspiring entrepreneurs through flagship programmes such as the National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Programme (NEIP) and the Ghana Enterprise Agency (GEA) [83]. To complement these efforts, the government keeps urging universities to be entrepreneurially oriented in their programmes. Universities could help hone entrepreneurial skills by implementing entrepreneurial support strategies, allowing their products to take advantage of available government funding opportunities.

No matter how innovative an entrepreneurial programme may look and be offered to students, its success can barely be realised without considering their entrepreneurial intention as a key variable, which is also influenced by entrepreneurial scaffolding and psychological capital. Several scholarly works have been conducted on the factors influencing EI from diverse dimensions. Recent studies specifically investigated psychological characteristics such as internal locus of control and personality traits as determinants of EI [84,85,86,87,88,89]. However, it is advised that emphasis be placed on developmentally-based psychological resources (PsyCap) and school-oriented support strategies (entrepreneurial scaffolding) because they are the key drivers of entrepreneurial behaviour [62,63,64,65, 90, 91]. Again, it is important to note that scaffolding and psychological capital (PsyCap) are frequently studied in education and health but are rarely employed in business-related areas like entrepreneurship [92, 93]. This creates a huge gap in the literature, and the current study seeks to bridge this gap by analysing entrepreneurial intention using entrepreneurial scaffolding and psychological capital (PsyCap) as predictors among Ghanaian universities. In this way, a representation of the underlying connection among variables will be established through the following hypotheses:

-

1.

H1: There is a statistically significant influence of entrepreneurial scaffolding on entrepreneurial intention among students in Ghana.

-

2.

H2: There is a statistically significant influence of psychological capital on entrepreneurial intention among students in Ghana.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

The study was about the predictive abilities of psychological capital and entrepreneurial scaffolding on entrepreneurial intentions. The study used an analytical cross-sectional survey in which final-year undergraduate students were recruited. The analytical cross-sectional design was chosen because several final-year undergraduate students that have entrepreneurship as a general course were identified from different locations and situations in Ghana. In all, 250 [94] students out of 2033 were selected through stratified and simple random procedures. The stratification was done because the universities had different populations, which required fair representation. To ensure fairness in the survey response cases, simple random sampling (a table of random numbers) was used.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Entrepreneurial scaffolding

Institutional entrepreneurial scaffolding is assessed using a HEInnovate self-assessment [99]. Students used the scale to evaluate the level of entrepreneurialism at their universities. The tool comprised 37 items across seven components: this allowed students to assess their entrepreneurial support, ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree. Leadership and governance (5 items), organisational capacity (5 items), entrepreneurial teaching and learning (5 items), preparing and supporting entrepreneurs (6 items), knowledge exchange and collaboration (5 items), the internationalised institution (5 items), and measuring impact (6 items). Sample statements on the seven components of the scale include: “Entrepreneurship plays a significant role in the strategic direction of my university. It is backed by diverse and sustainable financing and investment sources that support our business goals. The university provides various formal learning avenues aimed at fostering entrepreneurial skills. Moreover, the institution places great emphasis on the value of entrepreneurship and actively promotes collaboration and knowledge sharing with industry, the public sector, and society. Internationalization is a key aspect of the university’s entrepreneurial agenda, and regular assessments are conducted to evaluate the impact of our entrepreneurial initiatives.” The scale registered an acceptable internal consistency of 0.87 [95], which was less than the original internal consistency of 0.98.

2.2.2 Psychological capital (PsyCap)

Students’ psychological capital was measured using the Compound Psychological Capital Scale (CPC-12) [96]. The components are hope (3 items; e.g., “Right now, I see myself as being pretty successful”); resilience (3 items; e.g., “Sometimes I make myself do things whether I want to or not”); optimism (3 items; e.g., “The future holds a lot of good in store for me”) and self-efficacy (3 items, e.g., “I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort”). Items were answered using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree.” The scale recorded an improved internal consistency of 0.85 against the original reported value of 0.82.

2.2.3 Entrepreneurial intention

Adapted items from Linan and Chen [97] entrepreneurial intentions questionnaire (EIQ) were used to measure students’ plans to start their own business. These items are specifically designed to assess the intent to engage in entrepreneurial activities. The scale is uni-dimensional and has 5-items, with a sample item such as “My professional goal is to be an entrepreneur.” Items were answered using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree.” The internal consistency of the scale was 0.71, is less than 0.77 to 0.94 threshold established in the validation process.

2.2.4 Analysis

The data analysis was performed after taking data management into consideration. Specifically, multiple linear regression was used as the main statistical procedure because the aim of the study was to ascertain the contribution of the independent variables to the dependent variable.

3 Results

3.1 Gender of the participants

The pie chart (Fig. 1) reflects the gender of the participants, and it is evident that the number of female participants (N = 130) was slightly higher than the number of male participants (N = 120).

Descriptive statistics shown in Table 1 indicate that PsyCap generated the highest mean and standard deviation, followed by entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial scaffolding. The results of the departure from symmetry tests revealed that skewness statistics produced negative values less than zero, implying that the data were negatively skewed, whereas kurtosis statistics produced platykurtic (less peaked with fewer outliers) values less than 3 [98].

From Table 2, it is evident the variables correlated significantly among themselves, but there were no issues of multicollinearity among the predictors (ES and PsyCap) as the values of the variance inflationary factor (VIF) were all less than 2.

The results of the regression analysis of entrepreneurial scaffolding and psychological capital predicting entrepreneurial intentions among undergraduate students are shown in Table 3. The regression correlation shows that there is a large significant positive relationship among the variables. This implies that entrepreneurial scaffolding and psychological capital jointly explained 65.3% of the variance in students’ entrepreneurial intentions (R2 = 0.653, F (2, 247) = 154.14, p < 0.000). Further interpretation shows that there were significant predictions among the variables. For instance, entrepreneurial scaffolding experienced by students positively and significantly predicted students’ entrepreneurial intentions (β = 0.376, p < 0.000) while students’ psychological capital positively and significantly predicted their entrepreneurial intentions (β = 0.466, p < 0.000). The results imply that a unit increase in either entrepreneurial scaffolding or psychological capital will lead to a unit increase in students’ entrepreneurial intentions.

4 Discussion

In every region of the world, entrepreneurialism has played a crucial role in the economy. Managers are looking for graduates with an entrepreneurial spirit to help them deal with the ever-changing business world. This trend is fueled in part by ambitious and innovative entrepreneurs who want to start new ventures that shake up the business world and are looking for people with similar ideas. There is growing agreement that entrepreneurialism is not just a personality trait or a set of inherent attitudes but rather a learnable skill. The proliferation of college majors and certificate programmes focused on entrepreneurship is evidence of this trend. Also, entrepreneurial scaffolding aligns with the human capital theory. The human capital theory provides a valuable lens for understanding the role of education, skills, and training in shaping individuals’ capabilities and behaviours [99]. When applied to the context of entrepreneurship, human capital theory offers insights into the relationship between entrepreneurial Scaffolding as a developmental learning process and its impact on entrepreneurial intention. Relating human capital theory to entrepreneurial scaffolding, the theory posits that investing in education, training, and other forms of human capital development enhances individuals’ skills, knowledge, and capabilities, thereby increasing their productivity and future earnings potential [100]. Therefore, the acquisition of entrepreneurial skills and knowledge through educational interventions, such as entrepreneurial scaffolding, can positively influence individuals’ intentions to engage in entrepreneurial activities.

In light of these, the current study revealed that psychological capital influenced entrepreneurial intentions among students. This confirms previous findings, which revealed that psychological capital predicted the entrepreneurial ambitions of students [66,67,68]. Again, entrepreneurial scaffolding predicted the entrepreneurial intentions of students in the current study. The finding was in line with earlier studies. For instance, Liao et al. [45] found in a study that entrepreneurial scaffolding helps establish an entrepreneurial attitude towards starting a new firm. This was equally corroborated by [25, 46, 47], who found that entrepreneurial education curricula and university entrepreneurial encouragement encourage young people to pursue an entrepreneurial future.

5 Conclusion

The purpose of the study was to determine the psychological of entrepreneurial intentions among undergraduate students at a Ghanaian university. The study found that entrepreneurial scaffolding provided by higher education institutions and psychological capital positively influenced undergraduate students' drive to engage in entrepreneurial ambitions and behaviours. The findings shows that these undergraduate students regard the theoretical-based education and training offered as most laudable and may venture into personal enterprises after graduating. Undergraduate students’ intentions to engage in entrepreneurial activities may be motivated by constant reports from job market stakeholders that graduate unemployment continues to rise, necessitating the need for graduates to refocus and reorient their job prospects.

6 Recommendations for policy and practice

The goal of the study was to find out how entrepreneurial drives in universities (through entrepreneurial scaffolding) and mental assets (through psychological capital) affect the plans of first-year students at a Ghanaian university to start their businesses. The study found that entrepreneurial scaffolding provided by higher education institutions and psychological capital positively influenced undergraduate students’ drive to engage in entrepreneurial ambitions and behaviours. The revelation shows that these undergraduate students regard the theoretical-based education and training offered as most laudable and may venture into personal enterprises after graduating. Undergraduate students’ intentions to engage in entrepreneurial activities may be motivated by constant reports from job market stakeholders that graduate unemployment continues to rise, necessitating the need for graduates to refocus and reorient their job prospects.

According to the findings, activities related to careers, including career counselling, play a very important part in the development of entrepreneurialism. It is an irrefutable fact that without investment and appropriate career counselling for the development of human capital in all areas of need, no country can achieve sustainable development. As a result, career counselling courses on entrepreneurship need to be organised by counsellors and focused on educating students on how to be accountable, creative, innovative, and enterprising, as well as how to become employers of labour rather than job seekers.

There is no denying that each person behaves differently and that different situations lead to different behaviours. Therefore, career counsellors must provide themselves with relevant contemporary career theories so they can help people who are having career difficulties and understand their issues. Among the theories are trait and factor theory, or matching theory, decision theory, situational theory, developmental theory, and personality theory, to name a few.

An effective way to achieve educational sustainability is to incorporate career counselling on entrepreneurship as a course of study into the current university educational curriculum. As a result, career counselling on entrepreneurship choice of study should be a crucial component of an educational process that must be made mandatory for all students at tertiary institutions to create awareness of the world of work, a broad orientation to occupations, in-depth exploration of a chosen job cluster, career preparation, an understanding of the economics of jobs, and placement for all students. Again, educators in higher education should endeavour to include practical and innovative ways of teaching that will expose students to diverse career opportunities rather than focusing only on a theoretical orientation.

A career workshop should be organised on various campuses where already established entrepreneurs will share their experiences to boost the morale of students to start their businesses. In addition, alumni who have been able to make it can also share their experiences with students. Again, counselling professionals can prepare flyers that contain information on government and non-government institutions that provide support in different forms and share them with students. This will easily help them locate where to go for entrepreneurial support.

7 Limitations and future research directions

As much as the study findings have contributed to the literature in the area of entrepreneurship, they are not free from limitations. For instance, the study used only two higher education institutions in Ghana. Hence, concluding that the findings reflect all higher education institutions will be problematic. Therefore, future research should focus on all public and private higher education institutions in Ghana with diverse backgrounds that could influence the outcome. In addition, the study is more or less perceptual and does not reflect the entrepreneurial actions of those involved. As a result, future research should concentrate on tracer studies so that those graduating from higher education institutions can be tracked and studied in terms of entrepreneurial knowledge application.

Data availability

The data for this study is available and can be provided when a proper request is made to the authors. As of now, the authors reserve the right to follow ethical protocols by not uploading.

References

Mulikita JJ. Young people’s potential the key to Africa’s sustainable development. UN; 2022.

Meyer DF, Mncayi P. An analysis of underemployment among young graduates: the case of a higher education institution in South Africa. Economies. 2021;9(4):196.

Lacmanović S, Burić SB, Tijanić L. The socio-economic costs of underemployment. In: Management international conference, Pula, Croatia. 2016.

Wilkins R, Wooden M. Economic approaches to studying underemployment. In: Underemployment: psychological, economic, and social challenges. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 13–34.

International Labour Organisation. World employment social outlooks: trends for youth. Geneva: International Labour Organisation; 2016.

Berglund T, Håkansson K, Isidorsson T, Alfonsson J. Temporary employment and the future labour market status. Nord J Work Life Stud. 2017;7(2):27–48.

International Labour Office. Global employment trends for youth 2020: technology and the future of jobs. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2020.

Arthur-Holmes F, Busia KA, Vazquez-Brust DA, Yakovleva N. Graduate unemployment, artisanal and small-scale mining, and rural transformation in Ghana: what does the ‘educated’ youth involvement offer? J Rural Stud. 2022;95:125–39.

Mohseni M, Jouzaryan F. Examining the effects of inflation and unemployment on economic growth in Iran (1996–2012). Procedia Econ Financ. 2016;36:381–9.

Wu X, Tian Y. Predictors of entrepreneurship intention among students in vocational colleges: a structural equation modeling approach. Front Psychol. 2021;12: 797790.

Shane S, Venkataraman S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad Manag Rev. 2000;25(1):217–26.

Diandra D, Azmy A. Understanding definition of entrepreneurship. Int J Manag Account Econ. 2020;7(5):235–41.

Bhasin J, Gupta M. Entrepreneurial intentions of students in higher education sector. Amity J Entrep. 2017;2(2):25–36.

Moriano JA, Gorgievski M, Laguna M, Stephan U, Zarafshani K. A cross-cultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention. J Career Dev. 2012;39(2):162–85.

Cai Y, Zhao N. Analysis of college students’ entrepreneurial intention based on principal component regression method. High Educ Explor. 2014;4:160–5.

Kolvereid L, Isaksen E. New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. J Bus Ventur. 2006;21(6):866–85.

Maka L, Van Niekerk JA, DeBruyn M, Pakela-Jezile YP. Perceptions of agricultural postgraduate students on unemployment in South Africa. Int J Soc Sci Humanit Stud. 2021;13(1):55–78.

Wakefield HI, Yu D, Swanepoel C. Revisiting transitory and chronic unemployment in South Africa. Dev S Afr. 2022;39(2):87–107.

Daniel SU, Israel VC, Chidubem CB, Quansah J. Relationship between inflation and unemployment: testing Philips curve hypotheses and investigating the causes of inflation and unemployment in Nigeria. Traektoriâ Nauki Path Sci. 2021;7(9):1013–27.

Ighoshemu BO, Ogidiagba UB. Poor governance and massive unemployment in Nigeria: as causes of brain drain in the Buhari administration (2015–2020). Insights Reg Dev. 2022;4(2):73–84.

König AKP, Schmidt CVH, Kindermann B, Schmidt MAP, Flatten TC. How individuals learn to do more with less: the role of informal learning and the effects of higher-level education and unemployment in Ghana. Afr J Manag. 2022;8(2):194–217.

Lantolf JP, Poehner ME. Sociocultural theory and the pedagogical imperative in L2 education: Vygotskian praxis and the research/practice divide. London: Routledge; 2014.

Nordlof J. Vygotsky, scaffolding, and the role of theory in writing centre work. Writ Centre J. 2014;34:45–64.

Nambisan S, Siegel D, Kenney M. On open innovation, platforms, and entrepreneurship. Strateg Entrep J. 2018;12(3):354–68.

Scott JM, Penaluna A, Thompson JL. A critical perspective on learning outcomes and the effectiveness of experiential approaches in entrepreneurship education: do we innovate or implement? Educ + Train. 2016;58(1):82–93.

Tarling C, Jones P, Murphy L. Influence of early exposure to family business experience on developing entrepreneurs. Educ + Train. 2016;58(7/8):733–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-03-2016-0050.

Gibb A. In pursuit of a new ‘enterprise’ and ‘entrepreneurship’ paradigm for learning: creative destruction, new values, new ways of doing things and new combinations of knowledge. Int J Manag Rev. 2002;4(3):233–69.

Gianiodis PT, Meek WR. Entrepreneurial education for the entrepreneurial university: a stakeholder perspective. J Technol Transf. 2020;45(4):1167–95.

Liu X, Lin C, Zhao G, Zhao D. Research on the effects of entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on college students’ entrepreneurial intention. Front Psychol. 2019;10:869.

Entrialgo M, Iglesias V. The moderating role of entrepreneurship education on the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Int Entrep Manag J. 2016;12(4):1209–32.

Karimi S, Biemans HJ, Lans T, Aazami M, Mulder M. Fostering students’ competence in identifying business opportunities in entrepreneurship education. Innov Educ Teach Int. 2016;53(2):215–29.

Parker SC. The economics of entrepreneurship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018.

Nabi G, Liñán F, Fayolle A, Krueger N, Walmsley A. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: a systematic review and research agenda. Acad Manag Learn Educ. 2017;16(2):277–99.

Kierulff HE. Entrepreneurship education in Poland: findings from the field. Hum Factors Ergon Manuf Serv Ind. 2005;15(1):93–8.

Michaelides M, Benus J. Are self-employment training programs effective? Evidence from project GATE labour. Economics. 2012;19(5):695–705.

Mozahem NA, Adlouni RO. Using entrepreneurial self-efficacy as an indirect measure of entrepreneurial education. Int J Manag Educ. 2021;19(1): 100385.

Maresch D, Harms R, Kailer N, Wimmer-Wurm B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programs. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2016;104:172–9.

Minai MS, Raza S, BinHashim NA, Zain AYM, Tariq TA. Linking entrepreneurial education with firm performance through entrepreneurial competencies: a proposed conceptual framework. J Entrep Educ. 2018;21(4):1–9.

Schwarz EJ, Wdowiak MA, Almer-Jarz DA, Breitenecker RJ. The effects of attitudes and perceived environment conditions on students’ entrepreneurial intent: an Austrian perspective. Educ Train. 2009;51(4):272–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910910964566.

Feranita F, Mouawad R, Amin M, Leong LW, Rathakrishnan T. Unveiling the role of entrepreneurial education in preparing the next generation of entrepreneurs in Malaysia. In: Strategic entrepreneurial ecosystems and business model innovation. Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley; 2022. p. 17–30.

Yigitbas E, Sauer S, Engels G. Using augmented reality for enhancing planning and measurements in the scaffolding business. In: Companion of the 2021 ACM SIGCHI symposium on engineering interactive computing systems; 2021. p. 32–7.

Wahidmurni W, Pusposari LF, Nur MA, Haliliah H, Lubna L. The impacts of using modules on students’ entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions. Cypriot J Educ Sci. 2022;17(8):2634–45.

Dana LP, Tajpour M, Salamzadeh A, Hosseini E, Zolfaghari M. The impact of entrepreneurial education on technology-based enterprises development: the mediating role of motivation. Adm Sci. 2021;11(4):105.

Lv Y, Chen Y, Sha Y, Wang J, An L, Chen T, Huang X, Huang Y, Huang L. How entrepreneurship education at universities influences entrepreneurial intention: mediating effect based on entrepreneurial competence. Front Psychol. 2021;12: 655868.

Liao S, Javed H, Sun L, Abbas M. Influence of entrepreneurship support programs on nascent entrepreneurial intention among university students in China. Front Psychol. 2022;13: 955591.

Neto RDCA, Rodrigues VP, Panzer S. Exploring the relationship between entrepreneurial behaviour and teachers’ job satisfaction. Teach Teach Educ. 2017;63:254–62.

Van der Zwan P, Thurik R, Verheul I, Hessels J. Factors influencing the entrepreneurial engagement of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs. Eurasian Bus Rev. 2016;6(3):273–95.

Liguori EW, Bendickson JS, McDowell WC. Revisiting entrepreneurial intentions: a social cognitive career theory approach. Int Entrep Manag J. 2018;14(1):67–78.

Shamsudeen K, Keat OY, Hassan H. Entrepreneurial success within the process of opportunity recognition and exploitation: an expansion of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition model. Int Rev Manag Mark. 2017;7(1):107–11.

Kraaijenbrink J, Bos G, Groen A. What do students think of the entrepreneurial support given by their universities? Int J Entrep Small Bus. 2010;9(1):110–25.

Lim DS, Oh CH, De Clercq D. Engagement in entrepreneurship in emerging economies: interactive effects of individual-level factors and institutional conditions. Int Bus Rev. 2016;25(4):933–45.

Mustafa MJ, Hernandez E, Mahon C, Chee LK. Entrepreneurial intentions of university students in an emerging economy: the influence of university support and proactive personality on students’ entrepreneurial intention. J Entrep Emerg Econ. 2016;8(2):162–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-10-2015-0058.

Souitaris V, Zerbinati S, Al-Laham A. Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. J Bus Ventur. 2007;22(4):566–91.

Csikszentmihalyi M, Seligman M. Positive psychology. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):5–14.

Seligman ME. Helplessness: on depression, development and death. New York: Freeman; 1975.

Snyder CR, Lopez SJ. The future of positive psychology. In: Handbook of positive psychology. Cham: Springer; 2002. p. 751–67.

Cameron KS, Dutton JE, Quinn RE. An introduction to positive organizational scholarship. Posit Organ Scholarsh. 2003;3(13):2–21.

Costa S, Neves P. Job insecurity and work outcomes: the role of psychological contract breach and positive psychological capital. Work Stress. 2017;31(4):375–94.

Luthans F. Positive organizational behaviour: developing and managing psychological strengths. Acad Manag Perspect. 2002;16(1):57–72.

Lupșa D, Vîrga D, Maricuțoiu LP, Rusu A. Increasing psychological capital: a pre-registered meta-analysis of controlled interventions. Appl Psychol. 2020;69(4):1506–56.

Donaldson SI, Donaldson SI, Chan L, Kang KW. Positive psychological capital (PsyCap) meets multitrait-multimethod analysis: is PsyCap a robust predictor of well-being and performance controlling for self-report bias? Int J Appl Posit Psychol. 2021;7:1–15.

Darvishmotevali M, Ali F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: the moderating role of psychological capital. Int J Hosp Manag. 2020;87: 102462.

Margaça C, Hernández-Sánchez B, Sánchez-García JC, Cardella GM. The roles of psychological capital and gender in university students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Front Psychol. 2021;11: 615910.

Peters M, Kallmuenzer A, Buhalis D. Hospitality entrepreneurs managing quality of life and business growth. Curr Issue Tour. 2019;22(16):2014–33.

Stephan U. Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: a review and research agenda. Acad Manag Perspect. 2018;32(3):290–322.

Zhao J, Wei G, Chen K-H, Yien J-M. Psychological capital and university students’ entrepreneurial intention in china: mediation effect of entrepreneurial capitals. Front Psychol. 2020;10:2984.

Frese M, Gielnik MM. The psychology of entrepreneurship. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2014;1(1):413–38.

Contreras F, De Dreu I, Espinosa JC. Examining the relationship between psychological capital and entrepreneurial intention: an exploratory study. Asian Soc Sci. 2015. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v13n3p80.

Chevalier S, Calmé I, Coillot H, Le Rudulier K, Fouquereau E. How can students’ entrepreneurial intention be increased? The role of psychological capital, perceived learning from an entrepreneurship education program, emotions and their relationships. Europe’s J Psychol. 2022;18(1):84.

Maslakçı A, Sürücü L, Şeşen H. Positive psychological capital and university students’ entrepreneurial intentions: does gender make a difference? Int J Educ Vocat Guidance. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09545-z.

Salavou H, Mamakou X, Douglas EJ. Entrepreneurial intention in adolescents: the impact of psychological capital. J Bus Res. 2023;164: 114017.

Maslakçı A, Sürücü L, Şeşen H. Relationship between positive psychological capital and entrepreneurial intentions of university students: the mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. World J Entrep Manag Sustain Dev. 2022;18:305–19.

Wang XH, You X, Wang HP, Wang B, Lai WY, Su N. The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: mediation of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and moderating model of psychological capital. Sustainability. 2023;15(3):2562.

Bağış M, Kryeziu L, Kurutkan MN, Krasniqi BA, Hernik J, Karagüzel ES, Karaca V, Ateş Ç. Youth entrepreneurial intentions: a cross-cultural comparison. J Enterprising Communities People Places Glob Econ. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-01-2022-0005.

Maslakcı A, Sesen H, Sürücü L. Multiculturalism, positive psychological capital and students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Educ + Train. 2021;63(4):597–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-04-2020-0073.

Hmieleski KM, Carr JC. The relationship between entrepreneur psychological capital and new venture performance. Front Entrep Res. 2008. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1346023.

World Bank. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) finance. 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance.

Amaglo JK. Strategies for sustainability of small and medium enterprises in Ghana (Doctoral dissertation, Walden University); 2019.

Poole DL. Entrepreneurs and SMEs in Rwanda: the model pupil paradox. London: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2021.

Sodokin K. Access to microfinance institutions, official banks, and the impact on small business in Togo. Int J Econ Financ. 2022;14(1):1–46.

CEOWORLD. Magazine entrepreneurship index. 2022. https://citibusinessnews.com/2022/06/ghana-ranked-7th-best-african-country-for-entrepreneurs-in-2022-top-10-rankings/.

Bawakyillenuo S, Agbelie ISK. Environmental consciousness of entrepreneurs in Ghana: how do entrepreneur types, demographic characteristics and product competitiveness count? Sustainability. 2021;13(16):9139.

Agyapong D. Review of entrepreneurship, micro, small and medium enterprise financing schemes in Ghana. In: Enterprising Africa. London: Routledge; 2020. p. 142–58.

Arkorful H, Hilton SK. Locus of control and entrepreneurial intention: a study in a developing economy. J Econ Adm Sci. 2021;38(2):333–44.

Bazkiaei HA, Heng LH, Khan NU, Saufi RBA, Kasim RSR. Do entrepreneurial education and big-five personality traits predict entrepreneurial intention among universities students? Cogent Bus Manag. 2020;7(1):1801217.

Tentama F, Abdussalam F. Internal locus of control and entrepreneurial intention: a study on vocational high school students. J Educ Learn (EduLearn). 2020;14(1):97–102.

Uysal ŞK, Karadağ H, Tuncer B, Şahin F. Locus of control, need for achievement, and entrepreneurial intention: a moderated mediation model. Int J Manag Educ. 2022;20(2): 100560.

Wang J-H, Chang C-C, Yao S-N, Liang C. The contribution of self-efficacy to the relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention. High Educ. 2016;72(2):209–24.

Vodă AI, Florea N. Impact of personality traits and entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students. Sustainability. 2019;11(4):1192.

Saeed S, Yousafzai S, Yani-De-Soriano M, Muffatto M. The role of perceived university support in the formation of students’ entrepreneurial intention. In: Sustainable entrepreneurship. London: Routledge; 2018. p. 3–23.

Wegner D, Thomas E, Teixeira EK, Maehler AE. University entrepreneurial push strategy and students’ entrepreneurial intention. Int J Entrep Behav Res. 2019;26(2):307–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-10-2018-0648.

Huang L, Zhang T. Perceived social support, psychological capital, and subjective well-being among college students in the context of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac Educ Res. 2022;31(5):563–74.

Johnston C, Bradford S. Other lives: relationships of young disabled men on the margins of alternative provision. Disabil Soc. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2023.2209278.

Ritter NL. Understanding a widely misunderstood statistic: Cronbach’s. Online Submission; 2010. p. 1–17.

Nwana OC. Introduction to educational research. Ibadan. Nigeria: Heinemann Educational Books; 1992.

European Commission. Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions, a blueprint to safeguard Europe’s water resources. 2012.

Liñán F, Chen YW. Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep Theory Pract. 2009;33(3):593–617.

Westfall PH. Kurtosis as peakedness, 1905–2014. RIP. Am Stat. 2014;68(3):191–195.

Nadezhina O, Avduevskaia E. Genesis of human capital theory in the context of digitalization. In: European conference on knowledge management. Academic Conferences International Limited. 2021. p. 577–84.

Moreno-López G, Marín LMG, Gómez-Bayona L, Mora JMR. Knowledge production in universities: an analysis based on human capital theory, a case of accredited HEIs in Colombia. In: Developments and advances in defense and security: proceedings of MICRADS 2021. Springer Singapore; 2022. p. 529–39.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the participants for having time to take part in the study. Again, we thank all the research assistants for their unflinching support in the data collection.

Funding

Authors of this study had no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IM, PE, PMA, TA, BMA, and VEE are the authors of this study, and they contributed proportionally from the beginning to the end.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We sought permission from the participants using the informed consent form. Aside from this, the study was approved by the ethical review board of the University of Cape Coast.

Consent for publication

All authors have the consent of the publication of this article.

Competing interests

We have no conflicting interest in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahama, I., Eshun, P., Amos, P.M. et al. Psychological precursors of entrepreneurial intentions among higher education students in Ghana. Discov Educ 2, 29 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-023-00047-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-023-00047-w