Abstract

The emergence of China as a major provider of development finance has garnered considerable scholarly debate. Chinese investments and their impact on recipient states have been extensively studied, mainly focusing on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In response to the BRI, the European Commission recently announced its connectivity strategy, the Global Gateway initiative. In this context, and even before the announcement, little work has been done to map Chinese state capitalist development finance side by side with the European Union’s (EU) market-led, public-private partnership-oriented strategies, especially within Europe’s own neighborhood. Additionally, the literature insufficiently explains why development institutions (agents) would act geo-economically to enforce their most powerful member states’ (principals) international agendas. This lack of theoretical explanatory power poses a serious puzzle. Thus, we ask, how has EU and Chinese institutional investment cooperation developed (legally and financially) in the EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) region in the previous EU Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) from 2014 to 2020? We argue that development institutions have acted in accordance with their principal’s policy goals by facilitating investment and institutional agreements and by offering beneficial cooperation conditions, so that the EU and China can direct investment in a geo-economic manner if they choose to do so. In the following, we find that European investment in the EaP countries Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia, has been huge in absolute terms (amount invested) and strong in relative terms––through deeper economic cooperation––when compared to Chinese investment activity in the same countries. This development supports the EU’s aim of countering China’s increasing economic presence in the region. However, we find that this gap has been closing in total terms. Our study suggests that while China has not matched EU investment in the EaP region for the previous MFF, further research is needed to unpack individual sectors and their geo-economic implications for official development institutions and their respective states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The EU has produced increasingly critical policies and communiques regarding China’s global engagements in recent years. This turn concerns not only human rights issues within China but also Chinese activity in various EU member states and its immediate neighborhood (Blenkinsop and Emmott 2019). Additionally, the European Commission (EC) announced the Global Gateway (GG) initiative in 2019. European Commission President von der Leyen envisioned a multi-billion Euro plan, to provide sustainable and high-quality investments globally. Through its foreign and economic policy, the EC thus aims to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and to enhance its own political relations in dedicated geographical areas. One such increasingly contested area is the EU’s Eastern Partnership Region (EaP) (European Commission 2019). Large-scale exogenous shocks such as the Covid-19 Pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine have at the same time highlighted the EU’s economic dependence on illiberal regimes in Russia and China. The same is true for most of the EU’s neighboring economies. This paper will therefore focus specifically on efforts undertaken by European development institutions to advance their political and economic relations in the EaP region. Specifically, we will focus on the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia. Additionally, we reference investments from Chinese ministries, policy banks, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

The increased importance of state-induced investment emerges amid a shift in larger development frameworks. Gabor (2020) argues that the dominant Western development agenda has shifted from the Washington Consensus––defined by the free-market regulation, privatization, and with foreign direct investment based on policy conditions to these ends––to the “Wall Street Consensus,” wherein private finance takes a leading role, and state money is often used to “de-risk” or backstop investment projects. Yet, another understanding emphasizes the recent rise of China as a development actor, occurring combined with a broad ideological adjustment towards re-legitimizing the role of the state in development finance (Alami and Dixon 2020; Alami et al. 2021; Alami et al. 2022). While competing views, these frames are both helpful in understanding state behavior. In Europe specifically, development banks such as the EIB and EBRD absorb risks with the help of EU funds, giving development banks more financial avenues to govern and more ability to make risky investments. Through China’s emergence as a global investor, development finance also became an arena to contest liberal norms and values across its trading and development cooperation partners. With the Global Gateway also aiming at these EaP countries, all of which have a formalized relationship with the EU,Footnote 1 we investigate how these investments have developed with a geo-economic understanding in mind, even before the strategic announcements by the European Commission.

According to Commission President von der Leyen’s Global Gateway announcement, the European Union aims to compete with China in its connectivity strategy. This elicits the specter of a geo-political European Commission. In March 2023, von der Leyen stressed an imbalance with China that required correcting. Her strategy of economic de-risking follows along four pillars: increasing EU competitiveness and resilience, better utilizing existing trade instruments, creating new defensive tools for critical sectors, and aligning with partners in the G7 and G20 (von der Leyen 2023). Likewise, in a 2021 Joint Communique which included the EIB, the European Commission laid out the Global Gateway as a strategy for Europe to forge more resilient infrastructural and political connections around the world based on Brussels’ “strategic interests,” which include avoiding “economic coercion for geo-political aims” (High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy 2021). Considering the European Commission’s claims of geo-political intent and action, what does their past development cooperation tell us about these ambitions and how has EU and Chinese investment cooperation developed, even before strategic notions became more visible? Particularly, we ask: how have these developments played out in the EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) region in the previous EU Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) from 2014 to 2020? We argue that development institutions have acted in accordance with their respective principal’s policy goals by facilitating investment and institutional agreements and by offering beneficial cooperation conditions, so that the EU and China can direct investment in a geo-economic manner if they choose to do so.

Geo-economics rises to the fore as an analytical frame in part due to the self-professed geo-political nature of the European Commission, and due to its cooperation with European investment institutions, in addition to the attention it pays to Chinese investment activity. Geo-economics, as we will explain next, is a theoretical departure point for this paper. We synthesize recent geo-economics literature and demonstrate how a novel geo-economic view can help understand EU-driven investment vis-à-vis Chinese investment. Moreover, there is little literature on EU-dominated financial institutions and their actions in the EaPs vis-à-vis Chinese institutions and their development finance strategies. In the following, we will close this gap by providing a comprehensive account of European and Chinese institutional development cooperation activity in the EaP countries Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova from 2014 to 2020. This paper is structured as follows: in the next Section, we review the literature on geo-economics and identify its knowledge gap concerning development institutions. In Section 3, we present our cases, data, and methodology. We analyze our data in Section 4 and discuss our findings in Section 5. Section 6 concludes.

Breaking down geo-economics, synthesizing geo-economic institutions

Geo-economics offers a useful framework, not least because it departs from the widely understood character of the European Commission as a geo-political actor. In the past, President von der Leyen stated that the EC would take on a geo-political role, which inspired thorough scholarship on this topic (Haroche 2022; Petrovic and Tzifakis 2021; Zwolski 2020). However, a recently self-prescribed geo-political agenda would not explain if development institutions act geo-economically and in accordance to their principals’ agendas or on their own. While geo-economics has been mainly used to describe a subcategory of geo-politics between states, we draw inspiration from various scholars to propose an expansion of geo-economic thinking to development institutions. Next, we clarify these conceptual frames and show how they come together to explain how these institutions have advanced their development cooperation with each selected EaP. Most recently, and in line with our study, Haroche (2022, 4) discusses the EC as an actor with geo-political intentions, functioning in a geo-economic fashion, and emphasizes how asymmetric economic interdependence can be weaponized. Haroche’s work builds on interviews with Commission staff, who confirmed that China’s actions are a major influence on the strategy of the EC. Furthermore, the EC remains ready to compete with other institutional actors to promote the EU’s leadership on the world stage (2022, 5–6). However, current definitions of geo-economics are broad and often interchangeable with geo-politics or economic statecraft. The following we present the state of the art of geo-economics literature, wherein we synthesize our definition and its relative novelty in applying it to European development institutions.

Luttwak (1990, 19) initially introduced geo-economics as the logic of war in the grammar of commerce. Since then, scholars have offered similarly broad definitions, understanding only states as geo-economic actors, who conduct policy in a rather realist manner. These works offer valuable definitions of geo-economics, such as “the strategic [use] of economic instruments” (Vihma 2018, 11), the “geo-strategic use of economic power” (Wigell and Vihma 2016, 137), or even the use of “economic instruments to promote and defend national interests, and to produce beneficial geo-political results; and the effects of other nations’ economic actions on a country’s geo-political goals” (Blackwill and Harris 2017, 9). However, Sparke (2007, 2018) has critiqued this style of conception as merely an updated realism (limited by its instrumentalist focus) and instead emphasizes critique of geo-economic discourses and policy action. Balmas and Dörry (2022) further noted that, others take a distinctly broad understanding of geo-economics by emphasizing the discourse itself (Moisio 2018). But broad is not necessarily bad. Sparke’s critique highlights the potential limits of the instrumentalist focus and legitimizes our foray into this topic, inspired by von der Leyen’s discourse around geo-politics.Footnote 2

Then there are strict definitions, such as Kim (2021, 328), which proposes that geo-economics may only take place in the “[grand] strategy of great power competition” through the deployment of economic policies only by national governments with mid to long-term strategic interests in a specific geographical region. However, this is potentially too restrictive, mainly because it requires proof of a grand strategy – a herculean task given the nature of the EU as a unique state formation unlike any other. It is also clear from von der Leyen’s speeches that the EC wants institutions, even some of which are not strictly bound to the EU (such as the EBRD) to act as its agents. More applicable to our discussion are those recent contributions to the geo-economics literature, which have broadened the field of potential actors to include firms and commercial banks. Babić et al. (2022) note crucially that while Luttwak’s definition remains applicable, the modern complexity of global economics means the dynamics of international relations are more nuanced today. This is also true in light of the time when Luttwak originally wrote his analysis in the twilight of the Cold War and before the explosion of market liberalism in post-Communist countries under the Washington Consensus (Babb 2013).

Likewise, Balmas and Dörry (2022) extend the state-centered conception of geo-economics to involve firms, building on Dörry and Dymski (2021), who see asymmetric global capital-profit distribution as a geo-economic issue in and of itself. The authors point precisely to Chinese banks in BRI projects as an example of geo-economics, which involves not only states, but firms. This stance is similar to Babic (2021), who understands attempts at market control and capital extraction from abroad as falling under the rubric of geo-economics, demonstrated by mapping foreign state investments, wherein states could gain ownership of projects across borders. State development banks and their cooperation with commercial banks are also known to backstop and support firm investment activities (S. Kim 2022), which is similar but not identical to Gabor’s notion of de-risking (Gabor 2020). The term is precisely what EU and EU-associated development banks intent to do: they are there to act as market makers and de-risk in the interest of European strategy, as laid out by von der Leyen (Clifton et al. 2014; Clifton et al. 2018).

On the other hand, much has been written on the EU as a regulatory power extending beyond its borders and through its regulations, where it can shape the policies of countries inside and outside the bloc (Bradford 2015; Caporaso et al. 2015; Hadjiyianni 2021). Recent scholarship has also found that institutions such as the EIB and member state development banks can be understood as a hidden investment state within Europe (Mertens and Thiemann 2019). Likewise, the use of European commercial banks can be seen as a tool to signal strategic coercive power when banks act in the state’s interest in the economy. For instance, by disrupting liquidity provision, they can act as “devices of potential practices of state power” (Massoc 2022, 608). We suggest that therefore it is possible to conceive of the EU, managed by the European Commission, as a hidden investment state which can act outside of its own borders as well. Along these lines, we see development banks as arms of such a hidden investment state, which reach beyond the EU’s borders. This conception also departs from Massoc’s demonstration that banks’ “geo-economic structural power pertains to their involvement in development finance in the Global South” (Massoc 2022, 608). If, as the author points out, commercial banks can act as geo-economic actors, we should also include development banks into the theoretical framework as potential appendages of a state’s geo-economic action. This is especially true given the case of the EBRD, which is one part merchant commercial bank and another part development bank, which scholars point out acts as a market maker to pave the way for private investment in developing markets (Shields 2021, 2020; Piroska and Schlett 2023). Development banks can also act as pathfinders for commercial banks, which then act in geo-economic ways, and thus they should be included in geo-economics theorization (Massoc 2022, 608).

In sum, we define geo-economics as a state’s (principal) geo-strategy expressed through economic and development policy towards a willing recipient state, acted out by the state or state-connected agents, i.e., it’s geo-economic institutions (actors). This includes firms and more importantly development banks. These actors may be understood as geo-economic in character based on the mere intent of a given geo-political policy (drawing back to Sparke’s and Miosio’s emphases on discourse). The recipient state must also have similar interests (D. J. Kim 2021) and they do so in our study, as Moldova, Georgia, and Ukraine all desire EU membership and better connectivity to global trade routes. Taking the EC’s intent towards geo-politics seriously, we aim to unpack how EU-associated institutional investment and Chinese investment developed in the targeted region.Footnote 3

Of course, European, and Chinese investment institutions are not analogous actors. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB), and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) are regional multilateral development banks (MDBs). The China Development Bank (CDB) and China Export-Import Bank (CHEXIM) are unilateral financial institutions. Chinese ministries and agencies represent another unilateral category of development actors within this framework. These differences between the EU and China widen when comparing the constraints of their institutions. While Chinese official development institutions are virtually unconstrained when enabled by their government, the EBRD and EIB do face several regulatory and budgetary limitations in their investment operations. This paper will not harmonize these differences but rather work with the identified constraints for European institutions, to test whether they meet or miss their goals. To better understand this dynamic, we first ask how EU and Chinese development finance has developed along a series of economic metrics in a geo-economic and strategic context. We then investigate how EU development finance in these EaPs comports with EU strategizing from an institutional perspective. Given how the EC frames investments, they can be understood as part of a larger European regional strategy where European investment conditionality requires certain democratic changes and reforms among recipient countries.

In the following, we unpack how EU and Chinese development finance have developed in the EaPs in absolute terms (by amount) and relative terms (by consolidation of economic cooperation). While much has been written on Chinese investment as an element of China’s foreign policy, specifically in geo-economic terms (Garlick 2019; Morgan 2019; Shang et al. 2023; Stone et al. 2022; Yang and Liang 2019), and much on the EU in the same vein (Christiansen 2020; Haroche 2022; Petrovic and Tzifakis 2021), little literature exists on comparative development in the EaP region and especially regarding institutional aspects of geo-economics (Kim 2020). We will close this gap by providing an account of European and Chinese institutional development investment activity in Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova from 2014 to 2020.

Case selection, data and methodology

We employ a qualitative analysis of observational data to analyze EBRD and EIB, as well as Chinese investment activity in the EaPs throughout the previous EU Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) from 2014 to 2020. First, we present our case selection before providing information on our data selection process. We then explain how we unpack our research question through three case studies via the text analysis of primary sources (press releases) and secondary sources (newspaper review), supported by quantitative observational data of project-level investments.

The EU’s Eastern Partnership comprises six countries. Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine signed onto the joint initiative by the EU and its member states in 2009. The partnership is based on “common values and rules, mutual interests and commitments, as well as shared ownership and responsibility” (European External Exchange Service 2022a). However, since its inception, two states have fallen significantly short of these ambitions, namely Azerbaijan and Belarus. Additionally, Armenia and Belarus have joined alternative partnerships, such as the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union (Peel and Buckley 2017). Only Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova have sustained engagement with the EU, while at the same time scouting for alternative partners that could replace Russia’s economic influence in their countries, especially after the illegal annexation of Crimea and the onset of the Donbas War in 2014. The departure of Russia as a trusted economic and political partner, together with the emergence of China as a global investor under President Xi Jinping since 2013, make Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova strong representative cases of geo-economic action of the EU and China. Suppose investment institutions from two different states simultaneously develop relations with an Eastern Partnership (EaP) country. In this scenario, it would be unlikely to observe competition through changes in strategies aimed at increasing influence via investment.Footnote 4 However, a different situation arises if institutions from one state successfully enhance their cooperation and influence in the EaP country, while the other state’s institutions fall short despite their desire to progress. In such a case, we can observe geo-economic interactions, indicating a shift in economic influence and cooperation in the region.

We collected data from 2014 through 2020, representing the previous EU Multiannual Financial Framework. This time frame holds exceptional importance to the geo-economic analysis of development finance, as the EU and China have completed important cooperation agreements while simultaneously boosting their investments by size and project count. The period furthermore captures the initial phase of the BRI and China’s emergence as an investor in the EaPs. We use publicly available project-level investment data from the EBRD, EIB, AIIB, CDB, CHEXIM, and the Chinese Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM). We captured any investment, which we could not directly assign to one single institution, in the variable People’s Republic of China (PRC) as an individual investment actor. This way, we can capture the best possible range of Chinese projects while distinguishing development institutions for a section of it.Footnote 5 Specifically, we utilized the EBRD’s Project Summary Documents, the EIB’s project finder, the American Enterprise Institute’s China Global Investment Tracker, AidData’s China Global Finance dataset, Boston University’s China’s Overseas Development Finance Geospatial Analysis tool, as well as the AIIB’s official website to gather data on Chinese investments in EaP countries (American Enterprise Institute and Heritage Foundation 2022; AidData 2021; Boston University 2022; Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank 2022; European Bank for Reconstruction and Development 2022a; European Commission 2022b). Next, we applied a conservative strategy to clean our dataset and dropped observations (projects) that did not carry enough evidence of having been realized beyond the initial commitment level or project entry. Furthermore, we cleaned the dataset of all projects marked repaying or declined, or that were vague or in any way unverifiable (N = 126). Overall, 311 projects over 7 years remained for analysis. Finally, we amended our dataset with controls from established development finance metrics, such as Freedom House’s Governance Indicators, the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, and the IMF’s World Economic Outlook databases (Freedom House 2022; World Bank 2022; International Monetary Fund 2022).

Methodologically, we will first describe the EU’s institutional and legal angle towards cooperation and investment in the EaPs. We will also address the investment activities of European development institutions, which have moved beyond their formally intended areas of operation. In the following three case studies, we will then review the contents of institutional press releases by the European Commission, the European External Action Service (EEAS), the EIB, and the EBRD, concerning the deepening economic cooperation and investment activity of European development institutions. We contextualize these developments against Chinese institutional arrangements and investment activity in each EaP, respectively. We provide further graphical analysis of the collected quantitative data in each section. Having presented the key contents of our dataset and methodology, next, we explain the steps we undertake to unpack how EU lending has developed vis-à-vis Chinese development finance in EaP countries, over time and on a recipient level.

Advancing EU and Chinese development cooperation in the EaPs

In each of the three EaP countries––Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova––we find developing administrative and legal connections to the EU and China. At the same time, each country holds a set of bilateral agreements with the EU and China as well as their institutions. In the following, we unpack these legal developments and overlaps before presenting each case study, showcasing the economic developments between each donor region and the EaPs.

Creating a legal framework for investments and trade

Through its European Neighborhood Policy (ENP), the EU fosters cooperation with 16 economies along the EU’s edge, including Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova. For the previous MFF period 2014-2020, the three countries signed ENP Action Plans, receiving access to funds from the European Neighborhood Instrument (ENI) in turn for socio-economic reform packages. The total budget for the previous period was €15.4bn. The main thrusts of this key instrument were comprehensive offers to the EaPs (European Commission 2022c): the promotion of human rights and the rule of law to undergird sustained democracy; sustainable and inclusive economic, social, and territorial development, including integration into the EU internal market; mobility and people-to-people contacts in academia and civil society; and regional integration, including Cross-Border Cooperation.

Each Action Plan was laid out for a period of three to 5 years, reflecting the countries’ needs and capabilities, as well as its and the EU’s interests. Progress reports, the latest of which were released in 2014, have guided this process (European External Exchange Service 2022b, 2022c). Additionally, distinct economic agreements are in place for the three EaP countries, reached during the negotiations for the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTA) and in each Association Agreement (Rabinovych 2022). Subsequently, in Ukraine, the EU has removed 98.1% of its tariff lines, while Ukraine allowed 99.1% of industrial products tariff-free entry (European Commission 2022e). A similar agreement was reached with Moldova, which removed all tariffs in 2016, with some being entirely dropped after a transition period of up to 5 years. However, tariff rate quotas remain partly in place and are being renewed (European Commission 2022a). Most tariffs were also eliminated for Georgia while more efficient customs procedures were introduced at the same time (European Commission 2022d). These agreements allowed the EaPs to better access the EU’s single market and give European investors a regulatory frame to operate in these countries. In 2017, all three countries also agreed to additional socio-economic reforms to be implemented under the 20 Deliverables for 2020 agreement (European Commission 2017). These developments helped advance one of the EU’s key ambitions in the region: sustainable and inclusive growth, and social and territorial development with progressive integration into the EU internal market.

While the free trade- and association agreements demonstrate how the EU began accessing EaP markets, available data allows for further comparisons between EU and Chinese institutions. As laid out in Section 3, we identified five key actors in the EaPs since 2014: EBRD, EIB, CDB, CHEXIM, AIIB, MOFCOM, and the Chinese government (PRC). In the following, these official investors’ mandates and engagements will be assessed, and their investments will be visually analyzed: Fig. 1 provides an overview of the investment totals from 2014 to 2020. The EBRD was the biggest investor with an aggregated amount of est. €8.5bn. The EIB followed with est. €7.1bn, totaling EU Investments to €15.6bn. This is not surprising, as the EU formalized EaP cooperation in 2009 and thus has built its cooperation framework for much longer. Additionally, both institutions work closely with the EC to ensure the EU’s policy- and reform ambitions (European Commission 2023).Footnote 6 Thus, they engage in a coordinated investment strategy together with the European Commission.

Identified projects from China were at est. €6.78bn., with the biggest share of investment (est. €5.9bn.) not assigned to a single institution and denoted as PRC. The AIIB invested around €250mn., followed by the China Export-Import Bank with est. €180mn. Surprisingly, China’s Ministry of Commerce is ranked third with an est. €80mn. and before the China Development Bank.Footnote 7 Besides the MOFCOM’s position, the AIIB’s investment totals stand out for two reasons. First, a significant part of Chinese investment appears to be facilitated through multilateral funding and beyond its original intended geographical area of operation in Asia. Second, the institution began operations only in 2016 and is relatively transparent in its portfolio activity. Thus, it is very likely that these investments represent the true amount, compared to other Chinese investments.

To summarize, Fig. 1 provides us with the previous inventory of EU and PRC institutions active in EaP countries. Having identified the EU’s and China’s main institutional actors and their regional investment totals, we next show how European and Chinese institutions have been going abroad since 2014 to expand their operational areas and how they found new ways to pursue their domestic and geo-strategic policy goals and increased their investment activity.

Going abroad

Going abroad is a central aspect of this investigation. For the EU––and via the European Commission––the EBRD and EIB operate as dual arms of its foreign investment strategy and policy, enjoying shared “cooperative relations” and “goals [and] resources” (Piroska and Schlett 2023, 21). They also aim to influence policy debates and engage policymakers, as the European Commission incentivizes EIB action with so called carrot finance programs, such as InvestEU or through EIB co-investments together with the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIFs) and the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI) (compare Fig. 1.3 in Mertens et al. 2021). Furthermore, the EIB focuses on low-risk investments and EU-backed high-risk investments outside the EU, with 40% of total EIB lending going to the public sector compared to 2% of the EBRD’s portfolio (Shields 2021). Together with the EIB and European member states, the EU makes up 54% of EBRD’s total capital (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development 2022b). Together, these states dominate the bank’s management practices. Furthermore, the EBRD’s signature technical assistance financing is often filtered through preferences of legal and advisory firms, which operate as middlemen between EBRD and recipient states (Piroska and Schlett 2022, 10).

As the EIB and EBRD remain relatively autonomous, the European Commission has several measures to support or incentivize these institutions to raise private money or invest public funds. One is the Guarantee Agreement, under which a certain amount of the EIB’s foreign investments is covered through European Funds such as the European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus (EFSD+). Since 2017, these guarantees have grown from €25.8bn. to €40bn. in 2022 (European Commission 2022b). In 2014, Brussels additionally initiated the External Lending Mandate (ELM) to “leverage EIB financing and enhance the impact in third countries” and to protect it from potential financial risks in third countries such as the EaPs (Molemaker et al. 2018). These tools give the European Commission enough power to facilitate and manage its investment strategies through the EBRD and EIB.

Simultaneously, through the emergence of new institutional actors and investment offers, popular destination countries of financial investment gained leverage when negotiating to raise capital (Bunte 2019). In this context, it is important to note, that since 1999, the Chinese government has encouraged its companies’ going out policy to build favorable conditions for continued economic growth (in China), to increase external demand for Chinese goods, and to foster foreign trade. This was made possible through a strategy aimed at investing its vast foreign exchange reserves together with the renminbi, which lost a relative share in China’s investment finance but is still growing in total terms. Chinese state-owned banks were mandated to increase lending of foreign currencies to overseas borrowers sizably, and USD-denominated loans and export credits skyrocketed. In 2014, outward foreign direct investment reached $US 120bn., up from near zero at the turn of the millennium (Dreher et al. 2022, 55–56). Additionally, China’s MOFCOM was mandated to coordinate major projects in partner countries and cooperate with all relevant actors like Chinese and local ministries, policy banks, and state-owned enterprises (SOE) (World Bank 2017). According to Hoare et al. (2018), this endows the MOFCOM with influence over the procurement process and overall project decisions. The Chinese Development Bank and the China Export-Import Bank on the other hand, finance concessional loans to recipient governments, loans and export credits to Chinese companies, and private equity fund investments, as well as financial and technical support to borrowers, also hold significant power to undertake procurement and influence over how projects are managed and realized (Bräutigam 2011, 755–58). Lastly, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), can conduct operations within its own policy framework to deliver on its objectives, holding further autonomy over its procurement and investment strategies (Hameiri and Jones 2018, 781).Footnote 8

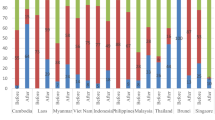

When looking at the mean investments of these institutions for each year in the past Multiannual Financial Framework, we can observe differences in the consistency of allocated investments in Fig. 2. While EBRD investments per year move in a range of €45mn. to €90mn., EIB investments range between €50mn. to €150mn. per year from 2014 to 2020. Converging to around €50mn., EBRD and EIB mean investments have stabilized since 2019. This progress could mean that investments flow more consistently or that the EaPs no longer attract huge funding from these institutions. Both may also be true at the same time. Chinese investments, on the other hand, move between €110mn. to €200mn. per year from 2014 to 2017 before reaching investment totals of €400mn. to €500mn. from 2018 to 2020. Mean investments from China’s banks (CDB, CHEXIM) dropped from est. €210mn. (2014) to est. €55mn. in 2015, before stabilizing at around €10mn. in 2016 and 2017. China’s MOFCOM investments remain at around €10mn. constant from 2014 to 2017. The AIIB follows a slight negative trend, with mean investments at around €110mn. in 2017 to €95mn. in 2020. What stands out is the sizable increase in Chinese investment, which cannot be assigned to any individual institution. These investments skyrocketed in 2017. In the same year, mean investments by the EBRD began to decline.Footnote 9 Through these mean investments, we observe consistent investment activity on the part of the EBRD and EIB, with financially lower endowed projects than PRC investments, which have visibly higher mean investments. While these government-driven Chinese projects outsize European investments, they are much more volatile.

For EaP countries, a donor’s investment in their economy has different implications. While the amount matters in terms of capacity building within each country, it is important to inquire about the relative size of these investments compared to each other. In Fig. 5 in Appendix, we report the growing number of Chinese investments in the region by EaP country. Georgia consistently received between €200mn. and €600mn. between 2014 and 2020.Footnote 10 Moldova received notable investments only after 2018 (est. €400mn.) and 2019 (est. €200mn.). Considering the size of their population and economy, these are substantial sums. Chinese investments in Ukraine hovered at est. €100-150mn. (2015, 2017) and est. €250mn. (2016) before skyrocketing to €1.5bn. to €1.6bn. in 2018 and 2019. In 2020, Ukraine received est. €300mn. Taken together, Chinese investments have been slowly increasing between 2014 and 2017, with sharp increases in Georgia. Between 2018 and 2019, these investments have increased threefold, with over three quarters allocated to Ukraine. Likely attributed to the Covid-19 pandemic, investments dropped to est. €900mn. in 2020, with no investments reported for Moldova. Compared to European investments (comp. Figs. 6 and 7 in Appendix), these Chinese investments show a sharp increase in investment activity in EaPs. In contrast, European investments remain stable between €1bn. and €2.6bn. from 2014 to 2019. For 2020 an increase in EBRD and EIB investments to est. €3.5bn. can be observed, likely a balancing measure to meet investment demand after China’s reduced investment activity during the Covid-19 pandemic. Thus, China’s inserted or withdrawn investment in the EaP stimulates the investment environment.

In this section, we have presented the mean investments over time and total amounts of European and Chinese official institutional investors in EaP countries. We have shown how the emergence of Chinese aid picked up after 2018 and how it possibly stimulated EBRD and EIB investments. In the following case studies, we describe the EU and China’s administrative and legal connections with each EaP and how each state holds a set of bilateral agreements with some institutions. In turn, these legal overlaps and distinctions will be unpacked, showcasing the economic developments between each group of actors and the EaPs.

Heterogenous regional outcomes for geo-economic institutions

The following three case studies describe how institutional actors have fostered bilateral relations between each respective EaP with the EU and China and their related economic developments. It examines official statements by the EBRD and EIB, as well as news reports on Chinese investments from 2014 to 2020, and investment-related visualizations to put these developments into perspective. As the ability to conclude economic and political cooperation agreements strongly indicates the relative market power of a given state investor and its institutions, we also compare how much market access the European and Chinese sides gained. As such, free trade agreements are a strong indicator of secured market access and will be a central aspect of our analysis.

Ukraine

According to Rabinovych (2022), the EU-Ukraine Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) constitutes an impressive scope of regulatory approximation and market integration, part of what is considered the most ambitious agreement that the EU has ever developed with any partner. Further, this trade agenda comprises the norms of the EU-Ukraine DCFTA, the unilateral financial and technical assistance instruments the EU uses to support the DCFTA’s implementation, and the prospects of further deepening trade between the EU and Ukraine, and acts as a “powerful instrument of facilitating internal reforms in Ukraine” (2022, 2). However, the implementation of the DCFTA has been and continues to be undercut by the war in Ukraine. At the time of her writing, Rabinovych noted that scholars deemed Ukraine’s progress to be mixed, with the DCFTA’s impact on European foreign direct investment considered limited until 2018. However, Ukrainian politics has largely seen lively and competitive democratic processes since signing the Association Agreement and DCFTA in 2014 (Rabinovych 2022). As a measure of EU interest in the country, within the 2014-2020 MFF period and after a brief drop from €3.4bn. in 2014 to €1.2bn. in 2015, the EU’s trade surplus with Ukraine exceeded €6.8bn. in 2020 (EuroStat 2021).

In 2015, EBRD President Chakrabarti also relayed the Bank’s support for Ukrainian internal reforms (Usov 2015), a month after calling for support towards Ukraine due to the war in the Donbas region (Williams 2015). The EBRD further noted in 2017 that Ukraine had made progress in the banking, power, and energy sectors but specifically stated that it needed to make more effort to consolidate the rule of law and respect for property rights, calling widespread corruption the most severe drawback on investment potential. The EBRD leadership also emphasized the need to remove barriers to foreign and domestic investment and its disappointment in the slow progress in privatization and reform of state-owned enterprises (Usov 2017). A year later, the Bank released its most recent Strategy for Ukraine, having organized meetings with civil society to consult on the process. This strategy aligned EBRD initiatives with initiatives of the International Monetary Fund towards public sector privatization, strengthening the rule of law, energy security, and financial integration (Usov 2018). In a 2019 visit to war-afflicted Eastern Ukraine, EBRD Vice President Alain Pilloux reiterated the bank’s strong commitment to the country, calling on the Ukrainian government to make great efforts towards recovering the assets of PrivatBank, which Ukraine nationalized in 2016. The Bank also emphasized signing agreements for new projects (Rosca 2019). This close cooperation can also be observed at the project level. For the previous Multiannual Financial Framework, EBRD projects far outmatched Chinese investments by number and topped EIB investments by 17, totaling 93 projects between 2014 and 2020 (see Fig. 3).

Shortly after the DCFTA was in place, the EIB signed its first private sector investment loan contract with Ukraine. The announcement referred to an assistance package announced by the European Commission, to which the EIB would contribute significantly, given that political and operational conditions were met (Tibor 2014a). The same year, EIB president Werner Hoyer met with the Ukrainian President and Prime Minister to commit to supporting Ukraine amidst the Russian annexation of Crimea and the Donbas War. In a public announcement, direct referrals were made to the EU comprehensive guarantee and the external lending mandate that back up all EIB loans to Ukraine (Tibor 2014b, 2014c). In the winter of 2015, EIB President Hoyer announced a cooperative project with the World Bank to help Ukraine avert a possible energy crisis (Tibor 2015). Another major co-financing loan contract, together with the EBRD, was announced in 2016. The same year, while holding a joint signing ceremony with the EC, EIB Vice-President Vazil Hudak reiterated the EIBs commitment to Ukraine, stating that their support for Ukraine is “cast iron and enduring” (Tibor 2016b) and continued to confirm that EIB investments fully aligned with European aims in Ukraine. While in 2016, the European Commission and EIB signed a multi-million Delegation Agreement for the DCFTA, the EIB announced that it would further raise its own-risk Neighborhood Finance Facility to €3bn., which even topped up the External Lending Mandate’s project support of €4.8bn. (Tibor 2017a). In 2020, an additional major infrastructure investment package was announced to foster “long-term social and economic development of eastern Ukraine and integration of the conflict-affected regions” (Tibor 2020b).

Conversely, economic relations between China and Ukraine declined drastically until 2015. This effect was primarily observed in lower trade levels, which only began slowly increasing again in 2016. In exchange for massive volumes of agricultural produce from Ukraine, China signaled investment interests in agriculture, infrastructure, and energy (Gerasymchuk and Poita 2018, 5). Cooperation continued in 2017 when Ukraine joined China’s BRI, signing a joint action plan, as well as cooperation agreements (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China 2017; OBOR Europe 2017). However, despite increases in investment activity, economic relations (as a means for some further end) between Ukraine and China did not pick up accordingly. On the contrary, Ukraine made clear that it favors economic ties with China but does not seek relations extending beyond BRI membership. Additionally, trade with China caused sizable trade deficits in Ukraine, from an est. $US 2.5bn. in 2014 to over $US 5bn. in 2019. This imbalance was further exacerbated by Ukraine’s one-sided supply of valuable military technology to China and the fact that Chinese investment into Ukraine did not meet Kyiv’s expectations. As economic participation in Ukraine remained low, Ukraine further pivoted toward the EU (Poita 2023, 314–16). And as Ukraine’s primary interests since 2014 did not fully align with China’s quest for new markets to establish itself as an economic and political actor, both sides could not overcome their strategic differences until 2020. This was further amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and China’s massive reduction in investment and trade activity (Ukraynets and Horin 2021).

To summarize, the EBRD and EIB were able to expand their investment operations in Ukraine continuously. These institutions strengthened their position, further backed by the EU’s political and financial support after Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and the Donbas War. These engagements even masked the huge trade deficit, the EU caused with Ukraine. On the other hand, China did not address Kyiv’s demands and could only achieve BRI objectives through government-to-government cooperation, while also causing unfavorable trade deficits. At the same time, its institutions did not advance their positions in Ukraine.

Georgia

According to European Commission reports, Georgia’s implementation of the DCFTA is well-advanced. From 2014 to 2019, EU trade sat in surplus, and Georgia “largely de-corrupted” its economy while its democratic institutions were slightly eroded by “the non-transparent role of a dominating oligarch, electoral irregularities and a (…) dysfunctional parliament” (Emerson et al. 2021a, 2021b, 14). Like Ukraine, Georgia has emerged as a potential hot spot for transport and logistics and has “largely approximated EU road transport legislation” (2021, 21).

In 2014, the EBRD underscored its commitment to Georgia as it prepared for further regional integration before developing the DCFTAs (Rosca 2014b). In 2015, the EBRD noted that Georgia had made significant progress on the issues of corruption, reform of government administration, and adopting a framework to enable a market economy (Balvanera 2015). Subsequently, Georgia and the EBRD established an Investors Council to align government representatives, state agencies, international investors, business associations, and ombudsmen (Martikian 2015). In 2015, the EIB opened its Regional Representation Office for the Southern Caucasus in Georgia’s capital Tbilisi. EIB Vice President Wilhelm Molterer called the office a major step in allowing the EIB to get closer to Georgia, allowing it to “better seize upon lending and technical assistance opportunities, and better assess and respond to … financing needs” (Tibor 2015). In its tenth anniversary, EIB Vice-President Hudak celebrated “ten successful years since we signed our Framework Agreement with the government and started looking for projects in which we could invest” (Tibor 2017b). Two years later, the Eastern Partnership Investment Forum celebrated its 10-year existence, during which the EIB signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Georgia reiterating its commitments towards close cooperation and support for Georgia’s public sector (Tibor 2019).

Likewise, China-Georgia relations also advanced when Georgia joined the BRI in 2016 (Sacks 2021). Since 2017, it furthermore remains the only EaP country with a free trade agreement with China (The Government of Georgia and The Government of the People’s Republic of China 2017). However, like for Ukraine, trade with Georgia shows a varying Chinese trade surplus of $US 640mn. in 2014 to $US 255mn. in 2016 and $US 655mn. in 2018 before falling sharply to $US 230mn. in 2020 (Trading Economics 2022a, 2022b). In 2019, China doubled down on BRI cooperation with Georgia during a visit of Prime Minister Wang Yi. During a high-level meeting with Georgian President Zourabichvili, Prime Minister Wang Yi did “a listening tour to know better about Georgian partner’s opinions on domestic and international issues and enhance mutual understanding, and also a pioneering tour to explore new fields of mutually beneficial cooperation” (Xinhua 2019). However, after the cancellation of the BRI Black Sea mega port project, a major blow, Chinese official institutional investors did not step in, leaving its trading partner without a Chinese offer to realize the project (Lomsadze 2020).

Figure 4 shows Chinese and European aggregated official investments per capita. Georgia stands out within the EaPs with an outsized share of incoming investments at around €75mn. to €150mn. per capita from Chinese official institutional investors annually from 2014 to 2020. Still, Georgia profited significantly from cooperating with China while also seeing per capita investments being disproportionately high, compared to European and Chinese investments into Ukraine or Moldova. While Chinese investments have steadily increased, the EBRD and EIB investments more than doubled since 2014, and even after China and Georgia signed their free trade agreement in 2016. While the EBRD and EIB dominate during the previous years of the MFF, China more than doubled its investments after 2016 and is closing the gap. This is unsurprising, as Georgia is a vital infrastructure hub between China and Europe and part of the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor. However, private-sector actors, such as the Hualing Group, also take center stage in facilitating investment between China and Georgia, side-lining Chinese institutions (compare Section 8.2, in Sahakyan 2023). Thus, strong investment activity of the EBRD and EIB on one side and China on the other may be primarily driven by domestic preferences instead of comparative developments within Georgia alone.

Moldova

Moldova has desired EU membership since 1991 (Całus and Kosienkowski 2018, 99) as it is entrenched in various geo-political spheres (Całus and Kosienkowski 2018, 103). The EU has historically given “substantial financial and technical assistance to Moldova” (Całus and Kosienkowski 2018, 112). However, from 2014 to 2015, election abuse and a hobbled government formation process led to a highly critical Commission Progress Report on Moldova (Całus and Kosienkowski 2018, 103). Recent years have also seen great political instability, but Moldova’s President Sandu and her Party of Action, which has held a majority in the Parliament since 2020, pursue a pro-democracy reformist agenda, operating in a context where even the pro-Russian Dodon party favors the implementation of the Association Agreement and EU DCFTA, which demonstrates “how deeply embedded the Europeanisation process is in Moldova’s political and economic realities” (Emerson 2021, 14).

In 2014, the EBRD set out a 2014-2017 Strategy for Moldova, with Julia Otto, the head of the EBRD office in Chisinau, voicing encouragement for the authorities to “persevere with further implementation of institutional reforms to ensure [an] independent and impartial judiciary, reduce corruption, further improve the business climate and strengthen the independence of the National Bank” (Rosca 2014a). In 2015, the Bank’s main concerns remained banking sector transparency and governance and Moldova’s weak judicial system. Two years later, the EBRD praised Moldova’s efforts towards reform which led to the approval of an IMF program in November 2016, highlighting in depth the ongoing transformation of Moldova’s banking sector (Rosca 2017a). The same year, EBRD leadership laid out a new Strategy for 2017-2022, prioritizing bank sector restructuring in transparency and corporate governance, supporting private firms, and privatizing public utilities and infrastructure (Rosca 2017b). One year before the MFF ended, EBRD Vice President Pilloux voiced further support for Moldovan reforms (Rosca 2019). Likewise, the EIB developed a cooperation framework in Georgia, together with the European Commission and EBRD. In 2014, a historical first-ever joint visit by EIB President Werner Hoyer and EBRD President Chakrabarti was taken to Moldova. The EIB signed a declaration of intent, naming the key areas of future cooperation (Rosca 2014a). Two years later, in an EIB press release on a railway investment, it was stated that “EIB, EU and EBRD funds will help to foster trade both in Moldova and between Moldova and its trading partners in the EU and Eastern Neighborhood region,” naming the EIB as an equal donor to the EBRD and EU (Tibor 2016a). In 2019, another large project was co-financed by the EIB, EBRD, and EU. At this point, the institution became the largest investor in the country (Tibor 2020a). However, Moldova remains the least invested in by “European” and “PRC” official investments, while its economy saw zero growth over the previous MFF period (compare Fig. 6 in Appendix).

Simultaneously, China was able to cooperate with Moldova early on for its connectivity strategy. The Moldovan-Chinese Intergovernmental Commission for Trade and Economic Cooperation oversaw the signing of a memorandum on Moldova’s engagement with the BRI early in 2014. Since then, both countries repeatedly desired to create a Free Economic Zone, signed further Memoranda of Understanding, and entered into continued negotiations in 2015 (Republic of Moldova 2015, 2017; Ministry of Commerce 2017b). With Moldova, China held a trade surplus of between $US 471.8mn. in 2014 and $US 351.8mn. in 2017 before reaching a surplus of $US 581.2mn. in 2019 and $US 529mn. in 2020 (Trading Economics 2022c, 2022d). However, negotiations for Chinese BRI projects to be conducted in the country stalled: only in 2019 did both countries reach their first-ever BRI deal on a project that the Moldavian government signed with two Chinese contractors over a 300 km road-infrastructure project (Tay 2019), leaving Chinese investments in the country unmatched by European engagement since 2014. What stands out in Moldova-China relations is the increased presence of China’s Ministry of Commerce, as its Vice Minister of Commerce Fu Ziying, took center stage in the free trade agreement negotiations (Ministry of Commerce 2017a) and subsequently also accounted for the biggest share of Chinese projects in the country (compare Fig. 3). It is worth noting that Moldova is the only of the three EaPs, where China was able to make significant advances, both in relative terms, through deeper economic cooperation, and in absolute numbers, such as investment volumes and project count. However, Chisinau’s demands for increased infrastructure investment were neglected by Beijing, which made Moldova rely again mostly on European investment. Furthermore, it remains unclear what drives China’s relatively high engagement with Moldova compared to Ukraine and Georgia (Maxim and Temur 2020).

Section 5 presented EBRD and EIB investments in Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova and unpacked the developments of EBRD/EIB-EaP economic cooperation and connected agreements. Furthermore, we analyzed the Chinese investment activity that Beijing developed over the previous MFF period. While the EaP economies in question have deeper trade and legal ties to the EU, the PRC increased its formal economic cooperation over the last MFF period. However, it also increased its trade surpluses in the region to the disadvantage of the EaPs. Next, we discuss these findings in a broader context.

Discussion

In this section, we discuss our findings and address the limitations of our investigation before giving concluding remarks on geo-economic dynamics in the EaP region from 2014 to 2020. We close with a post-pandemic outlook on said economic cooperation.

This paper analyzed EBRD, EIB and Chinese investment activity in the EaP region from 2014 to 2020. We observed that European development cooperation outmatched Chinese investment activity. Initial investment amounts appeared to reflect the geographical size and (status) of individual EaP countries vis-a-vis their respective official institutional investors. Still, their effects become less salient when compared to common economic controls such as GDP or government expenditure. Similarly, we have shown that, through a geo-economic lens, European official institutional investors are doing much for European goals in the EaP region for the previous MFF period. This comes with little surprise considering the EU’s strong engagement in developing its economic relations with Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia. The EU, as a hidden investment state, expands its operating area beyond the EU’s borders to achieve geo-strategic ambitions and policy goals. This engagement defines the relationships between the European Commission, EBRD, and EIB. Comparing the three case studies, it is clear from before (and after) Russia’s war against Ukraine, that Ukraine has proven the key target for European geo-economic investment. Its DCFTA was endowed with ambitious goals and investments, and it received far more EBRD project approvals compared to China offers Additionally, it obtained sizable loans from the EIB for the eastern regions suffering from the Donbas War. Lastly, even before the war, Ukraine did not want Chinese financial involvement to go beyond the Belt and Road Initiative. Georgia, on the other hand, while it had de-corrupted its country, could not even gain accession status like Moldova did. Both countries remained far behind any EU engagements in the selected EaP group. Simultaneously, China continued to expand its engagements in these areas but also gave them less attention in terms of invested totals. Thus, based on our understanding, and current events, Ukraine has been and will remain the main target of European geo-economic investment going forward.

At this point, it is important to note that we can only scratch the surface of Chinese investments, as China does not disclose investments publicly. Therefore, we relied on the most robust sources and methodologies to gather data on Chinese official institutional investments. However, this is where a second limitation comes into effect: We simply know too little about CDB, CHEXIM, and MOFCOM institutional engagements in the EaP, with little to no primary sources available and only partial secondary literature dealing with these actors (American Enterprise Institute and Heritage Foundation 2022; AidData 2021; Boston University 2022). While this is the second-best option, AidData today remains the most comprehensive collection of Chinese investment from 2000 to 2014 (UNDP China 2021). Together with the AEI’s and Boston University’s investment trackers, we’ve built the most comprehensive dataset from the available and widely cited list of Chinese-verified investment datasets (Ray et al. 2021, 4). The consistency of European norm enforcement remains another question. For instance, the EU’s reluctance to punish Hungary for its authoritarian slide and the EBRD’s involvement in authoritarian Egypt (Piroska and Schlett 2022), raises questions about Europe’s capacity to act coherently. Given its composition––China and the US are also members––the EBRD is interestingly quicker to critique a country for lack of progress on reforms, at least in our case studies. The EIB, however, a bit closer to a true representative of the EU than EBRD, seems not to levy critiques so much. This contradiction remains interesting and could warrant further investigation.

Since the end of the previous MFF, global markets have additionally undergone more exogenous shocks due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The virus and policy responses affected almost every facet of the global economy, international partnerships, and public opinion on globalization. Major economic blocs like the EU or economic heavyweights like China have come under pressure to adjust their geo-political goals to the post-pandemic era. However, this does not mean the geo-economic interactions studied in this paper have vanished. On the contrary, since the outbreak of Covid-19, advanced and emerging economies have increasingly called for more connectivity, investment, and deeper partnerships. In 2021, the G7 introduced its Build Back Better World Initiative (B3W) (White House 2021). Only 1 year later, the G7 updated its bid with the $US 600bn. endowed Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment to directly counter China’s global engagements (Shalal 2022). Similarly, China has introduced the Global Development Initiative (GDI) to steer the UN’s 2030 Agenda “in a new era of international development cooperation” (Ministry of Commerce 2022). Yet, it is too early to say how the GDI will address post-pandemic economic realignment globally and in the EaP region as major BRI projects continue to phase out or are abandoned (Minxin 2019).

Finally, throughout our paper, it became clear that the EU’s liberal market relations established with the EaP countries predominantly benefited the richer parties (EU and China alike) while putting the poorer party (EaPs) into a less beneficiary position. Neither did the EaPs share in World GDP (PPP) develop, nor could we see government expenditure rise significantly during the pre-pandemic years until 2020 (compare Fig. 6 in Appendix).

Conclusion

This paper has investigated how European and Chinese investments in Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia developed in the EaP region. We aimed to fill a gap in the recent geo-economic discourse on the dynamics of development institutions and provided an account of European and Chinese institutional activity in selected EaP economies. We asked firstly how EU and Chinese development finance developed along a series of economic metrics in a geo-economic and strategic context, we then looked at how EU development finance in these EaPs comports with EU strategizing. We argue that development institutions have acted in accordance with their principal’s policy goals by facilitating investment and institutional agreements and by offering beneficial cooperation conditions, so that the EU and China can direct investment in a geo-economic manner if they choose to do so.. This study finds that European investment in EaP countries has been strong in absolute terms (by amount) and relative terms (through deeper economic cooperation) to address China’s increasing economic presence in the region, if the EC wanted to act geo-economically, but the gap has been closing in total terms. Indeed, we show that the EBRD and EIB outmatched Chinese investments by the amount and project count visibly. However, Chinese investments have increased notably after 2016, reaching peak investment levels that begin to catch up to European investments. At the same time, the Covid-19 pandemic appears to have had a dual effect. While European investments have shown a major upward trend, Chinese official institutional investment activity collapsed for that year.

Similarly, the EU’s activity, leading to various free trade and association agreements and further EaP commitments for socio-economic reform, has outmatched Chinese ambitions beyond signing each EaP to the BRI and reaching an FTA with Georgia in 2017. Thus, we found the European competitiveness for the past Multiannual Financial Framework was given due to the EBRDs and EIBs capabilities of providing vast sums of investment to EaPs and by their continuous engagement with these recipient states. Similarly, socio-economic developments in EaPs indicate a trend toward the EU, as outlined in Section 5. These findings are valuable additions to the existing literature on EBRD and EIB investments in the EU’s Neighborhood strategy and give a novel institutional account of geo-economic investment policies. Our study also informs the discourse on Chinese economic activity in the EaP countries Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova before and during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Future research may investigate individual and sectoral projects and how they must be seen from a geo-economic perspective. Furthermore, field research could deliver valuable findings about the effects of investments on public opinion: Are European and Chinese investments in EaP recognizable to a given country’s population, do people associate said investments with China or the EU, or do they become just another infrastructural project for local communities?

Availability of data and materials

Data available upon request.

Notes

All three states have signed Association Agreements (AA) since 2016, and of which all applied for and obtained EU membership status (except for Georgia, which has not been granted candidate status so far).

However, this is not to say that we do not see geo-economics as precluding a realist motivation, as we will demonstrate in our discussion of the EBRD and its recent departure from norm enforcement.

Just as we allow our definition more flexibility beyond mere instrumentalism, we are also not making any causal claims and do not aim to determine the competitiveness or success of the policies on the part of any state.

We do not aim to unpack whether actual competition took place, rather a perceived competitive environment is guiding this point to best analyze how development cooperation between EU and Chinese actors and each respective EaP was unfolding.

Our main objective is to show how European institutions compare to Chinese investment, through a geo-economic understanding. Whether we can identify and link all Chinese investments to an institution is therefore secondary to our assessment.

For more information on formalized cooperation outside the EU between the European Commission, EBRD, and EIB, please see EC-EIB-EBRD Tripartite Memorandum of Understanding (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, and European Commission 2012).

Since we can observe a strong weight on the EU’s side, we must take into consideration that while China is outsized by EU finance, it remains a strong unilateral contributor while EU-dominated banks are administered by representatives of dozens of states.

We understand, for the purposes of this paper, the AIIB as a Chinese related actor because of their role in founding it, as well as their veto power in its operations.

We do not infer causal relations from this development. However, the converging trend of EBRD, EIB investments happen at the same time as the increased investment volumes from China.

One exception is 2018, for which we could not obtain data.

References

AidData. 2021. Global Chinese development finance dataset, Version 2.0 https://www.aiddata.org/data/aiddatas-global-chinese-development-finance-dataset-version-2-0.

Alami, I., and A.D. Dixon. 2020. The Strange geographies of the ‘new’ state capitalism. Political Geography 82: 102237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102237.

Alami, I., A.D. Dixon, R. Gonzalez-Vicente, M. Babic, S.-O. Lee, I.A. Medby, and N. de Graaff. 2022. Geopolitics and the ‘new’ state capitalism. Geopolitics 27 (3): 995–1023. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2021.1924943.

Alami, I., A.D. Dixon, and E. Mawdsley. 2021. State capitalism and the new global development regime. Antipode 53 (5): 1294–1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12725.

American Enterprise Institute, and Heritage Foundation. 2022. China global investment tracker https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/.

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. 2022. Project list https://www.aiib.org/en/projects/list/index.html.

Babb, S. 2013. The Washington consensus as transnational policy paradigm: Its origins, trajectory and likely successor. Review of International Political Economy 20 (2): 268–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2011.640435.

Babic, M. 2021. State capital in a Geoeconomic world: Mapping state-led foreign investment in the global political economy. Review of International Political Economy 30: 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1993301.

Babić, M., A.D. Dixon, and I.T. Liu. 2022. The political economy of Geoeconomics: Europe in a changing world. In International Political Economy Series. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-01968-5.

Balmas, P., and S. Dörry. 2022. The Geoeconomics of Chinese bank expansion into the european union. In The political economy of Geoeconomics: Europe in a changing world, ed. M. Babić, A.D. Dixon, and I.T. Liu, 161–185. International Political Economy Series. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-01968-5_7.

Balvanera, B. 2015. Georgia on the threshold of tomorrow. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development https://www.ebrd.com/news/2015/georgia-on-the-threshold-of-tomorrow.html.

Blackwill, R.D., and J.M. Harris. 2017. War by other means: Geoeconomics and statecraft. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Blenkinsop, P., and R. Emmott. 2019. EU leaders call for end to ‘naivety’ in relations with China. Reuters March 22, 2019, sec. Business News; https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-china-idUSKCN1R31H3 .

Boston University. 2022. China’s overseas development finance http://www.bu.edu/gdp/chinas-overseas-development-finance/.

Bradford, A. 2015. Exporting standards: The externalization of the EU’s regulatory power via markets. International Review of Law and Economics 42: 158–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2014.09.004.

Bräutigam, D. 2011. Aid ‘with Chinese characteristics’: Chinese foreign aid and development finance meet the OECD-DAC aid regime. Journal of International Development 23 (5): 752–764. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1798.

Bunte, J.B. 2019. Raise the debt: How developing countries choose their creditors. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Całus, K., and M. Kosienkowski. 2018. Relations between Moldova and the European Union. In The European Union and its eastern Neighbourhood, 99–113. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Caporaso, J.A., M.-h Kim, W.N. Durrett, and R.B. Wesley. 2015. Still a regulatory state? The European Union and the financial crisis. Journal of European Public Policy 22 (7): 889–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.988638.

Christiansen, T. 2020. The EU’s new normal: Consolidating European integration in an era of populism and geo-Economics. Journal of Common Market Studies 58 (S1): 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13106.

Clifton, J., D. Díaz-Fuentes, and A.L. Gómez. 2018. The European investment bank: Development, integration, investment? Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (4): 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12614.

Clifton, J., D. Díaz-Fuentes, and J. Revuelta. 2014. Financing utilities: How the role of the European investment bank shifted from regional development to making markets. Utilities Policy 29 (June): 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2013.10.004.

Dörry, S., and G. Dymski. 2021. Will Brexit reverse the centralizing momentum of global finance? Geoforum 125: 199–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.003.

Dreher, A., A. Fuchs, B. Parks, A. Strange, and M.J. Tierney. 2022. Banking on Beijing: The aims and impacts of China’s overseas development program. New edition. Cambridge ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Emerson, M. 2021. Deepening EU Ukrainian relations. Updating and upgrading in the shadow of Covid-19. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Emerson, M., D. Cenusa, and T. Akhvlediani. 2021. Deepening EU-Moldovan relations: Updating and upgrading in the shadow of COVID-19. Rowman and Littlefield International.

Emerson, M., T. Kovziridze, T. Akhvlediani, and G. Akhalaia. 2021. Deepening EU-Georgian relations: Updating and upgrading in the shadow of Covid-19 https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=3032445. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. 2022. EBRD project summary documents https://www.ebrd.com/work-with-us/project-finance/project-summary-documents.html. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. 2022. EU: EBRD shareholder profile https://www.ebrd.com/who-we-are/structure-and-management/shareholders/european-union.html. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, and European Commission. 2012. EC-EIB-EBRD Memorandum of Understanding https://www.ebrd.com/downloads/news/MoU_EC-EIB-EIF-EBRD_Final_MB_formatting.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Commission. 2017. Eastern partnership - 20 deliverables for 2020 focusing on key priorities and tangible result https://tinyurl.com/3be3zy72. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Commission. 2019. Commission reviews relations with China, proposes 10 actions https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_1605. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Commission. 2022. EU-Moldova deep and comprehensive free trade area https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/content/eu-moldova-deep-and-comprehensive-free-trade-area. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Commission. 2022. European Commission - EIB agreement investments worldwide https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_2870. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Commission. 2022. European neighbourhood instrument (ENI) https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/what/glossary/e/european-neighbourhood-investment. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Commission. 2022. European Union, trade in goods with Georgia https://tinyurl.com/5n6h2kda. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Commission. 2022. EU-Ukraine deep and comprehensive free trade area https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/content/eu-ukraine-deep-and-comprehensive-free-trade-area. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European Commission. 2023. Coordination with the European bank for reconstruction and development https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/investment-support/coordination-european-financial-institutions/coordination-european-bank-reconstruction-and-development_en. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European External Exchange Service. 2022. Eastern partnership https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eastern-partnership_en. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European External Exchange Service. 2022. ENP action plans https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/enp-action-plans_en. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

European External Exchange Service. 2022. ENP Progress reports https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/enp-progress-reports_en. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

EuroStat. 2021. Ukraine-EU - International Trade in Goods Statistics https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ukraine-EU_-_international_trade_in_goods_statistics. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

Freedom House. 2022. Freedom in the world research methodology https://freedomhouse.org/reports/freedom-world/freedom-world-research-methodology. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

Gabor, D. 2020. The wall street consensus. Development and Change 52 (3): 429–459. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/wab8m.

Garlick, J. 2019. China’s principal–agent problem in the Czech Republic: The curious case of CEFC. Asia Europe Journal 17 (4): 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-019-00565-z.

Gerasymchuk, S., and Y. Poita. 2018. Ukraine-China after 2014: A new chapter in the relationship. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Kyiv https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/ukraine/14703.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

Hadjiyianni, I. 2021. The European Union as a global regulatory power. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 41 (1): 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqaa042.

Hameiri, S., and L. Jones. 2018. China challenges global governance? Chinese international development finance and the AIIB. International Affairs 94 (3): 573–593. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiy026.

Haroche, Pierre. 2022. A ‘Geopolitical Commission’: Supranationalism meets global power competition. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, November, jcms 13440. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13440.

High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. 2021. Joint communication to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee, the committee of the regions and the European investment bank the global gateway Document 52021JC0030. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021JC0030 . Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

Hoare, A., L. Hong, and J. Hein. 2018. The role of investors in promoting sustainable infrastructure under the belt and road initiative https://bit.ly/3mYULBF. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

International Monetary Fund. 2022. World economic outlook, report for selected countries and subjects https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/April/weo-report. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

Kim, D.J. 2020. Making Geoeconomics an IR research program. International Studies Perspectives 22 (3): 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekaa018.

Kim, D.J. 2021. Making Geoeconomics an IR research program. International Studies Perspectives 22 (3): 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekaa018.

Kim, S. 2022. Personal networks, state financial backing, and foreign direct investment. Comparative Political Studies 56 (7): 1000–1028. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140221139382.

Lomsadze, G. 2020. Georgia cancels contract for Black Sea Megaport. Eurasia.Net https://eurasianet.org/georgia-cancels-contract-for-black-sea-megaport. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

Luttwak, E.N. 1990. From Geopolitics to Geo-Economics: Logic of conflict, grammar of commerce. The National Interest 20: 8 https://www.jstor.org/stable/42894676?seq=1. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

Martikian, L. 2015. Georgia and EBRD establish investors council. European bank for reconstruction and development https://www.ebrd.com/news/2015/georgia-and-ebrd-establish-investors-council.html. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

Massoc, E.C. 2022. Banks’ structural power and states’ choices on what structurally matters: The geo-economic foundations of state priority toward banking in France, Germany, and Spain. Politics and Society 50 (4): 599–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323292221125565.

Maxim, U., and S. Temur. 2020. China’s relations with Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova: Less than meets the eye. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. December 31: 2020 https://carnegiemoscow.org/commentary/83538. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.