Abstract

Drawing on a field survey of 116 villages in rural China conducted by the authors in 2005, we analyze whether and to what extent the official electoral institutions, as administered by local government, were a system that was consistent with the public preferences of villagers. We find a positive correlation between public opinion and actual electoral institutions; that is, if more villagers believed a certain electoral institution was ideal, the probability increased that such an electoral institution was implemented in practical village elections. The opinion-policy linkage, however, suggests that central government interventions and pressure from villagers’ collective protests were more effective than institutionalized and regular deliberations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Whether governmental policies should follow or reflect public opinion has long been the topic of intense debate in the public opinion literature, and current scholarship focuses primarily on the public opinion-policy-making relationship in mature democracies.Footnote 1 Meanwhile, the lack of an opinion-policy link non-western regimes is tacitly accepted (Wilezien and Soroka 2007) as news media and outlets of public opinion are heavily regulated by the authorities. Both of these factors are widely believed to be inevitable contributors to the dearth of vocalized public opinion. Moreover, because under such a regime, the major officials and even the whole bureaucratic system are appointed by higher authority, politicians have few incentives to respond to the preferences of ordinary citizens, since they run no risk of losing their offices. As a result, the opinion-policy relationship appears to be a spurious issue in nondemocratic regimes.Footnote 2

However, this pessimistic view of the opinion-policy relationship under a non-western regime may be an oversimplified approach. In this vein, recent literature renders two potential mechanisms through which policy-makers pay attention to people’s preferences and take action on the public’s behalf in an authoritarian context. One mechanism suggests that politicians may not turn a blind eye to what ordinary people prefer because they are concerned with the legitimacy of their ruling (Przeworski 1986) and are dependent upon a certain threshold of public support to remain in office (Geddes 2003; Haber 2006). Therefore, they likely offer what their citizens want to stave off revolution (Wintrobe 2000; Acemoglu and Robinson 2006). An implication of this reasoning is that political elites in non-western democracies should be sensitive to popular resistances, such as riots and protests, to which people frequently resort to signal and demonstrate their dissatisfactions and appeal for change (Goldstone and Tilly 2001). Another compelling logic is that dictators who are “stationary bandits” (Olson 1993) not only need the cooperation of local officials to maintain their ruling but also have an incentive to take advantage of citizen opinions to strengthen the high-level monitoring of subject officials’ performance (Huang 1995) to improve local governance and ensure growth. Undoubtedly, both mechanisms point to an opinion-policy linkage in a non-western context.

In this research, we examine whether and to what extent the formation of village electoral institutions matches up to public opinion in rural China. Data for this study are from a survey conducted by the authors that was originally designed to examine the status and impact of village elections across the country in 120 villages, 60 townships, and 30 counties located in six provinces. All of these villages held their most recent village committee elections in 2004 or 2005. Due to uncontrollable factors, including natural disasters (floods) and lack of coordination from local governments, we were only able to collect data in 116 villages, 58 townships, and 30 counties. The respondents (surveyed villagers) totaled 1918.

A critical feature of these data is that they contain both information on what actual electoral institutions are in practice and what types of electoral institutions are regarded by ordinary villagers as ideal. For the former, we asked five respondents (including one incumbent village committee cadre, one candidate in the last election, and three ordinary villagers) what electoral institutions were officially implemented in the last election. For each type of electoral institution, the answer with the highest frequency was taken as the correct response. For the latter, we elicited the preferences of surveyed villagers by asking them to describe their ideal electoral institutions.Footnote 3 By measuring this “ideal institutions vs. actual institutions” gap, we find that the actual electoral institutions were more likely to be implemented in practical elections if more villagers believe that these are ideal institutions.

However, in this type of cross-sectional study, the tight opinion-institution linkage suggests at best correlation rather than the direction of causation,Footnote 4 and we cannot assess the dynamic changes in the opinion-policy linkage. Despite this limitation, we find a positive opinion-institution correlation in China’s rural elections. This finding is consistent with what the “legitimacy concern” and “stationary bandit” logics predict in that the opinion-institution linkage resulted primarily from the intervention of the central government and was conditional on the pressure from villagers’ collective protests.

This research also speaks to the scholastic work on government responsiveness in developing countries, which typically assesses whether politicians and bureaucrats are more likely to implement policies congruent with citizen preferences. The current literature usually assumes electoral accountability, i.e., elections are fair and open so that accountability pressures are thought to promote more responsive policy-making (Ofosu 2019). We add to the literature by studying what electoral institutions villagers in China prefer in an environment in which rural grassroots institutions per se are outcomes of interplays between different social actors, including villagers, local governments and officials, and higher authorities, thereby focusing on what types of institutions come into being in the first place. Second, by examining how the opinion-policy link in China is affected by villagers’ collective action and the center’s regulation of rural elections, our research also echoes a growing literature on the importance of collective resistance in informing policy-making in China, especially as a pressure mechanism to force governments at various levels to respond to citizens’ preferences and demands (Chen et al. 2016; Heurlin 2016).

Do electoral institutions reflect the preferences of villagers?

In China, salient political reform was not initiated until the late 1980s. In November 1987, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress approved a provisional Organic Law of Village Committee (OLVC) that regulates how village polity should be organized. The law was revised and made permanent in 1998. According to the law, the villager committee is a community administration set up to manage village affairs. In addition, elections must be held every 3 years for positions on the village committee.

Does public opinion matter?

There are a sizable number of village election studies on China’s village electoral institutions. Many researchers have observed that the village election implementations in China not only have been undergoing substantial changes over different periods but also demonstrate considerable geographical variations across localities. First, many students of the village election agree that village electoral institutions, including issues such as voter registration, setting up steering committees, candidate nominations, etc., have been improved in the last two decades. An increasing number of villages have held fair and open elections (O’Brien and Han 2009). On the other hand, the formation and implementation of electoral institutions have shown astonishing variances in different places.Footnote 5 The nature and quality of electoral institutions and their impacts have also drawn enormous attention. Free, fair, and open elections not only have much bearing on local political life, for instance, enhancing feelings of political efficacy and making elected leaders more accountable to villagers (Li 2003; Kennedy et al. 2004; Manion 1996), they also influence villagers’ political attitudes (Manion 2006; Shi 1997; Chen and Yang 2002; Su et al. 2011) and citizenship consciousness (O’Brien 2001) and increase village public investments (Luo et al. 2007).

The body of literature mentioned above, however, omits one salient issue; that is, are elections implemented in a fashion that fits with the villagers’ preferences? In practice, it is the local county and township officials who have the final say on determining which official electoral institutions will be implemented in village elections. We might reasonably conjecture that the gap between official institutions and public opinion will be substantial. However, as suggested by both the legitimacy concern and stationary bandit arguments, the central government shall have a strong incentive to ensure that local governments conduct village elections in a manner that meets villagers’ preferences out of the consideration of either boosting legitimacy or improving the local government’s governance, or both. The pressure from above can, without question, limit the local government’s ability to manipulate electoral institutions in ways that do not respect the will of the villagers.

In addition, the logic of legitimacy concern indicates the importance of villagers’ likely reactions to official electoral institutions, in which the interplay between villagers and local government can intervene between the demand of the former and the decision-making of the latter. In this regard, villagers in and of themselves differ greatly. While some villagers may behave like passive bystanders, others are never subservient. In fact, in many villages, we found that if villagers perceived the official electoral institutions to be discriminatory, unfair, or unjust, they may implicitly or explicitly demonstrate their dissatisfaction, by, for example, refusing to vote on election day. In one village election in Jiangsu Province, for example, the local government attempted to interfere with the election by stipulating that villagers could only elect candidates nominated by local officials. The disaffected villagers protested by not voting on election day so that the required minimum number ballots for the election result to be valid was not obtained. Eventually, the local government was forced to change the nomination method to achieve a decent turnout.Footnote 6

On some occasions, villagers took more assertive approaches, such as petitioning to a higher authority to resolve their complaints,Footnote 7 which can cause problems for local officials. In one village in Jilin Province, the village cadres told us that if village election does not proceed in an open and fair manner, then candidates will appeal to the provincial authority. Villagers can also initiate collective actions that are more confrontational.Footnote 8 In another village election in Heilongjiang Province, the township cadres tampered with vote counting to guarantee the election of their favored candidate. When their deceit was revealed, the angry villagers spoiled the ballot box, interrupted the election, and besieged the local officials sent by the county government to oversee the election. Ultimately, the election proceeded according to the villagers’ preferences and the county party boss was forced to resign.Footnote 9 These events confirm the finding that public defiance is an effective way of generating pressure on local governments to push for popular policies (O’Brien and Li 2006; Tang 2005).

In addition to imposing direct pressures on local governments, the indirect impact of villagers’ collective resistance on the opinion-policy relationship can also be prominent. That is, villagers’ collective petitions, protesting, riots, etc., regardless of whether they are election-relevant or not, change how local officials view them. From past experience, local officials have learned of the strength of villagers as a group and can foresee what will take place if they fail to meet the public’s preference. If they want to minimize the risk of facing angry villagers, they will avoid provoking them with their policy-making. In other words, by signaling their collective action capacity to local officials, villagers’ collective resistance can force them to be more attentive and responsive to what villagers want, including their demands for ideal electoral institutions.

The relationship between public opinion and the official institutions we discuss above may not represent causality, i.e., both villagers’ preferences and official electoral institutions might be reflective of the influence of an omitted variable. As mentioned above, the OLVC requires the practice of village self-governance, and more than that, it provides a general framework as well as some concrete guidance on how to implement village elections, such as voting methods and candidate nominations. Therefore, the OLVC could affect the local government’s formulation of electoral institutions; at the same time, it may affect villagers’ perceptions of the nature of electoral institutions since villagers, as suspected by some theorists, may lack knowledge of and experience regarding what institutions are optimal for them and, thus, simply take those stipulated by the center as the best options if they have trust in the central government (Li 2010). We will address this problem in our empirical analysis in the next section.

Measuring explanatory and dependent variables

In practice, a village election is administered through a set of officially implemented electoral institutions that regulate the way that candidates are nominated, voter qualifications, voting methods, the validation of election results, and so forth. As mentioned earlier, local governments have decisive weight in determining which electoral institutions will be implemented in the villages under their jurisdictions. As a result, different villages can have their own official electoral institutions. Corresponding to each official electoral institution implemented in the election, we asked questions about villagers’ perceived ideal electoral institutions (Appendix 1), from which we learned the preferences and views of villagers. The explanatory variable can be derived from these questions. For example, the first question (direct/indirect election question) asks, “Do you think the village committee election should be a direct election (village committee leaders are elected by villagers’ ballots) or be an indirect election (village committee leaders are elected by villagers’ representatives)?”. Based on respondents’ answers, we are able to learn what they perceive the ideal institutions to beFootnote 10 and the proportion of those who hold a specific opinion in a village. The dependent variable is created as a dichotomous (0-1) variable to code the existence of a specific implemented official institution. For example, regarding the direct/indirect election question, if a direct election is implemented in a village, then in this case, the dependent variable is assigned the value of 1; otherwise, it is assigned the value of 0.Footnote 11 Correspondingly, the explanatory variable is defined as the proportion of villagers whose preference is identical to the implemented institution.Footnote 12 Since there are a total of 21 questions included in Appendix 1, we finally have 21 separate dependent variables and 21 corresponding explanatory variables.

Estimation and the results

We use the OLS method to investigate the relationship between villagers’ opinions regarding the ideal electoral institutions (explanatory variable) and the official electoral institutions implemented (dependent variable). The testing equation is as follows:

where subscripts i and h indicate the ith village (i = 1, …, 116) and the hth (h = 1, …, 21) official electoral rule (OEI) or villagers’ perception (Opinion) of the ideal electoral rule. OEI is the actual electoral rule implemented in an election, which is assigned the value of 1 if a specific rule was implemented in the election and a value of 0 if otherwise. Opinion is the proportion of villagers who favored that rule. Because OEI is a dichotomous variable that only takes the value of 1 or 0, we estimate Model 1 using the logit method. If the actual rules are reflective of public opinion, we will expect the estimated coefficient β to be positive and statistically significant. The implication is that the greater the percentage of people supporting or favoring an electoral institution, the more likely it is that the institution will be implemented.

Column 1 of Table 2 reports the estimation results for Model 1 for all 21 issues, which reflect the policy-opinion relationship from various aspects. In 14 out of 21 issues, the policy-opinion relations are found to be significant, and the coefficients have the expected signs. These results suggest that, for most issues, the actual electoral rules are indeed consistent with villagers’ opinions. We can further calculate the marginal effect of opinion on the actual electoral institutions implemented, which is calculated as the OEI elasticity of Opinion. For example, a percentage point increase in the proportion of villagers who believed that in the election, it is necessary to set up a secret voting booth (the 3rd issue) corresponds to a 3-percentage point increase in the probability that in the election, secret voting booths were set up. From Column 2, we know that among the 14 significant policy-opinion relationships, nine of them can be regarded as strong because their elasticity coefficients are greater than or equal to 1, while the remaining four can be regarded as relatively weak because their elasticity coefficients are smaller than 1.

In addition to Model 1, we employ a second strategy to investigate the policy-opinion relationship by redefining the explanatory and dependent variables. When interviewing villagers, we know not only how many of them hold the same opinion on a specific electoral institution but also the opinion with the highest frequency. In other words, we know what electoral institutions most villagers prefer.Footnote 13 Therefore, public opinion on a particular electoral institution in a village will be calculated as the proportion of respondents who share the view with the highest overall frequency. For instance, if we randomly surveyed 5 respondents in one village by asking them, “What do you perceive to be the optimal voting method?” (the 2nd question in Appendix 1), and 3 of them gave the answer of “one-voter-one-ballot”; 2 of them gave other answers (e.g., “one-household-one-ballot,” or “one-representative-one-ballot”); then, the public opinion regarding the “optimal voting method” issue is “one-voter-one-ballot” because most respondents held this view, and this index takes the value of 0.6 (=3/5). Using a similar method, we can determine the public opinions for other ideal electoral institution issues and calculate the values for these public opinion indices.

Correspondingly, the new dependent variable is whether an implemented electoral institution is congruent with the preferences of most villagers. If the preference of most villagers with regard to the optimal voting method is “one-voter-one-ballot” and the official institution implemented in the election is also “one-voter-one-ballot,” then we assign the value of the dependent variable to be 1 (otherwise 0), which means the implemented institution is congruent (otherwise incongruent) with most villagers’ preferences for the voting method. The strength of the newly introduced definitions is that they enable us to analyze to what extent policy-making reflects what most people want for each type of electoral institution, which is similar to the congruence notion emphasized in the comparative democracy literature (Golder and Stramski 2010). Another appealing feature of the new definitions is that they place the preferences of villagers and local officials across different types of electoral institutions on the same metric to make possible the assessment of the overall relations between election implementation and opinion.

By redefining explanatory and dependent variables in this way, we then test the following model:

Here, Opinion’ is defined as the highest proportion of villagers who shared the same belief regarding what the ideal electoral institution ought to be. CON measures whether the official electoral institution that is in force in the village is congruent with the preferences of most villagers, which takes the value of 1 if the official institution is congruent with what most villagers prefer and the value of 0 if otherwise. Because CON is still a dichotomous variable that only takes the value of 1 or 0, we will estimate Model 2 by using the logit method. If official electoral institutions tend to be congruent with public opinion, the estimated coefficient ρ should be positive and statistically significant. The implication is that as the size of the majority increases,Footnote 14 the more likely it is that the policy is congruent with public opinion.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of public opinion on each type of ideal electoral institution across villages (Opinion’1-21, Panel A) as well as the proportion of villages in which policy is congruent with opinion (CON1-21, Panel B) for each type of institution. As Panel A shows, the mean of Opinion’ is very high, ranging from 56% (Opinion’9) to 98% (Opinion’21). This means that for each type of electoral institution, in many villages, the highest villager preference proportion also has a majority, and sometimes even an absolute majority, status.

Panel B provides more information about responsiveness in terms of opinion-policy connections in the countryside. On average, the proportion of villages where the implemented official institutions are congruent with most villagers’ preferences is quite high, ranging from 54% to 100%. For example, in regard to the direct/indirect election issue, 92% of villages (the mean value of CON1 across all villages) have actual institutions that are in harmony with most villagers’ preferences. Regarding the 20th issue (the necessity of sending local officials to supervise village elections), the congruence level (the mean value of CON20 across all villages) even reaches 100%.

Table 2 reports the estimated results of Model 2 for all 21 issues. From these results, we find a significantly high level of congruence between official electoral institutions and the views shared by most villagers, which is indicated by the positive and significant estimated coefficients of Opinion’ (The lone exception is the last issue, Question 21, which asks, “Do you think the result of the election should be announced immediately after polls close?”). These results suggest that as the size of the majority who hold the same opinion increases, the probability that the implemented electoral institution is congruent with the majority preference will accordingly increase.

Table 2 also reports the marginal effects of public opinion (Opinion’) on the opinion-institution congruence level (CON). These marginal effects tell us the changes in probability of having an opinion-institution congruence produced by a one percentage point increase in the size of the majority, ranging from 0.1 percentage points (Opinion’4) to 2.3 percentage points (Opinion’6). For example, for the direct/indirect election issue, if the highest proportion of villagers who have the same preference in total villagers (Opinion’1), for example, preferring a direct election to an indirect election, increases by one percentage point, the probability that the official institution stipulates that the election is a direct election will increase by 0.3 percentage points. Similarly, a 1 percentage point increase in the highest proportion of villagers who prefer secret voting booths (Opinion’3) corresponds to a 1 percentage point increase in the probability that in an actual election, secret ballot booths will be set up (CON3). Put simply, what most villagers wanted indeed was reflected by the official electoral institutions.

Assess the overall opinion-policy linkage: a holistic perspective

Both Model 1 and Model 2 test the opinion-policy relationship for all 21 issues individually. Although this helps us examine the opinion-institution relationship from various aspects of an election, it does not tell us from a holistic perspective if and to what extent official electoral institutions mirror public opinion. In other words, what is the overall opinion-policy relationship in village elections?

To examine this overall opinion-institution relationship, we create two new opinion-institution indices to determine whether the official institutions, from a holistic perspective, match the preferences of most villagers. To create the new dependent variable, we first average the scores across CON1 through CON21 and then use the averaged value to measure the overall congruency of the official institutions with the institutions that most villagers prefer.

Regarding the new explanatory variable, we use the principal component analysis (PCA) method to combine all Opinion’s, from Opinion’1 to Opinion’21, into principal components, which are the linear combinations of all the original variables (Opinion’i). We take the first principal component as the final variable representing the overall public opinion regarding the ideal electoral institutions. This new variable accounts for 84% of the original information embodied across all Opinion’s.Footnote 15 PCA is the ideal choice when we need to measure a phenomenon that is not precisely reflected in any given variable. Thus, analysts are not forced to choose the variable that best reflects the phenomenon, nor is the covariance between several variables that measure the same phenomenon important. Finally, the value of the new independent variable is therefore the score of the first principal component, which is derived from the calculation of the first principal component. A higher value of this index indicates a greater size of the majority who share the same preference regarding what the ideal electoral institutions ought to be.Footnote 16

By doing so, we estimate the following equation:

where ACONi is the average value of CONih, where subscript h indicates the hth type of electoral institution (h = 1, …, 21). Therefore, ACON is a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 1, which suggests that we can estimate Model 3 by using the general linear method (GLM) with a logit link function (Papke and Wooldridge 1996). PCA-Opinion’i is the score of the first principal component of all Opinion’ih. If the overall opinion-policy relationship still holds, the coefficient β should be positive and pass the significance level. The implication is that as the majority size becomes greater, the degree of congruence between the actual institutions and the ideal institutions will be greater.

In addition, in Model 3, we also control for the effects of other relevant variables. The controlling set X includes Income, which is the average household net income of a village (in logarithmic form). Democratic theory posits socioeconomic development level as an environment that has a shaping and conditioning influence on the political system’s characteristics and which then affects how much policy-making is responsive to public opinion (Weber and Shaffer 1972). By controlling for the effect of income level, we can examine whether public opinion is able to influence policy-making, regardless of whether a village is poor or rich. Education is the percentage of the villagers who have finished at least the primary high schooling. Those people who receive more education are more knowledgeable and more likely to be able to affect policy formulation and make institutions more congruent with their preferences. Therefore, we expect a higher education level to be associated with a higher degree of congruency between institutions and the majority preference. Party is a dichotomous dummy variable that is assigned a value of 0 if the village party secretary was elected or nominated by all party members with the one-voter-one-ballot method, or a value of 1 if it was appointed by the party committee cadres or by the higher party authority. Thus, Party represents the extent to which the party-state controls the village party branch. Many observers have noted that village party branches, as the vehicle through which the party state interferes with village affairs, are likely to impair village democracy. We expect that an autonomous party branch is conducive to opinion-policy congruence. Town-cadre is the proportion of households with at least one family member who is a cadre in town or county government. Once village cadres have a tight link with the local government, they tend to rely on the patronage network to abuse their power and disregard villagers’ preferences, which suggests a lower degree of policy-making responsiveness to public opinion. Regulation indicates whether the local government directly assigns mandatory production tasks to the households living in a particular village, for example, requiring them to grow particular types of crops. Regulation is therefore a dichotomous dummy variable that is scored 1 if such regulations exist and 0 otherwise. The more mandates a local government assigns to peasants, the more it tends to hinder village democracy, as they fear more democracy encourages more resistance from farmers (Zhang et al. 2006). We expect Regulation to be negatively associated with the congruency between the majority preference and official institutions. Finally, we control for county fixed effects in Model 3.

To date, the specification of Model 3 does not take villagers’ resources into account. The legitimacy concern argument, however, points to the importance of citizens’ capacity to articulate their demands and impose pressure on both the central and local governments. To capture this mechanism, we add the variable Protest, which is a dichotomous variable indicating whether a village experienced large-scale collective protests 3 years before the time when the last election was held, and the interaction term Protest*PCA-Opinion’ into Model 3. We define a collective event involving at least 50 villagers as a large-scale collective protest event. It is worth noting that the collective resistance in our sample was due to disputes regarding village electoral institutions, land appropriations, birth planning, village corruptions, and so forth. This shows that the Protest variable stands for a broad environment in which local officials are under pressure from villagers from various aspects so that they can anticipate what will probably happen due to a large opinion-institution gap. In our survey, large-scale collective protests took place in 15 out of 116 villages.

In addition, as mentioned in Section 2, we need to consider the impact of the OLVC, which reflects the will of the central government. In fact, 10 out of the 21 survey questions (question 1-6, 8, 9, 19, 21) in Appendix 1 are specifically addressed by relevant articles in the OLVC. If we take these 10 questions out of the simple bivariate logit estimation in Model 1 and Model 2, then the effect of public opinion on electoral institution formation decreases. As Table 2 shows, among the remaining ten estimations, five of them in Model 1 now have marginal effects that are greater than 1, while in Model 2, only three have marginal effects greater than 1. This suggests that the pressure from the central government is a considerable driving force behind the tight opinion-institution connection. In addition, the enactment of the OLVC may affect the policy-making process and villagers’ perceptions of electoral institutions simultaneously, engendering the endogeneity problem. To address these positional problems associated with the influence of the OLVC, we employ a different estimation strategy in which all 10 institutions that are legally required by the OLVC are taken out of the calculation of ACON and PCA-Opinion’ and then we re-estimate Model 3.

Table 3 reports the estimated results of Model 3. In Panel A, we present the results when all 21 survey questions (Appendix 1) are included in the empirical analysis. Not surprisingly, in both columns, PCA-Opinion’ has a positive and very significant estimated coefficient, which indicates that an overall policy-opinion relationship indeed holds strong. These results show that, after controlling for the effects of other independent variables, official electoral institutions indeed reflect what most villagers prefer. In Column 1, the marginal effect of public opinion on the aggregate opinion-institution connection can be derived from the estimated coefficient of PCA -Opinion’. When other variables are fixed at the mean levels, a percentage point increase of PCA -Opinion’ at its mean level leads to a 0.22 percentage point increase in the overall level of congruence of official institutions with the majority preferences.

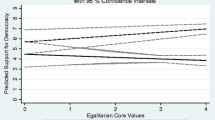

In Column 2 of Panel A, both PCA-Opinion’ and the interaction term Protest*PCA-Opinion’ are statistically significant at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively. These results substantiate that the presence of large-scale collective protests before village elections likely forced local policy-makers to pay more attention to the preferences of villagers. In addition, based on the estimation results, we can infer that on all occasions, the marginal effects of public opinion are greater when there were collective protests (protest = 1) than when there were no collective protests (protest = 0), as shown by Fig. 1(a1). The average marginal effect of PCA-Opinion’ when there were protests suggests that a unit increase of PCA-Opinion’ corresponds to a 10%age point increase in the level of congruence, whereas when no protests take place, a unit increase of PCA-Opinion’ on average led to only a 3 percentage point increase in the level of congruence. In addition, Fig. 1(a2) shows the change in the marginal effect of Protest against the varying values of PCA-Opinion’ when other variables are fixed at their means. The results are very interesting in that the marginal effects of Protest are negative when the size of the majority (PCA-Opinion’) stays low. However, as the size of the majority increases, the impacts of Protest also increase and finally become significantly positive after the size of the majority attains a certain level (PCA-Opinion’ = 4.56). This indicates that government officials in effect behave in an opportunistic fashion when facing disobedient villagers; that is, when the size of the majority is small, the local government tends to take a hardline approach to the powerless by, e.g., denying their demands for ideal electoral institutions. In fact, this result is consistent with the finding that peasants’ collective resistance may backfire, as they may provoke the local government to become more suppressive (Cai 2008). Our analysis here shows that only when the majority becomes sufficiently large, which probably means the pressure of collective resistance is worth noting, is the government willing to take villagers’ preferences seriously.

(a1): Marginal effect of villagers’ opinions. (a2): Marginal effect of collective protesting. (b1): Marginal effect of villagers’ opinions. (b2): Marginal effect of collective protesting. Note: (a1) and (a2) are based on the estimation results of Column 2 in Panel A of Table 3; (b1) and (b2) are based on the estimation results of Column 2 in Panel B of Table 3. PCA-Opinion’i is the score of the first principal component of all Opinion’ih (public opinion on an ideal electoral institution, measured as the highest proportion of villagers who shared the same belief regarding what the ideal electoral institution ought to be)

On the other hand, if we exclude the institutions with the force of law (OLVC) from consideration, the significance of PCA-Opinion’ disappears, which is shown by the results in Panel B of Table 3. In Column 1, for example, the coefficient of PCA-Opinion’ is no longer significant in the two-tail test, although it is barely significant at the 10 percent level in the one-tail test. In Column 2, the coefficients of PCA-Opinion’ are far from achieving conventional statistical significance. This suggests that for the electoral institutions that are not required by OLVC, the opinion-policy linkage becomes rather weak. However, an encouraging finding is that in Column 2, Protest and the interaction term Protest* PCA-Opinion’ are still statistically significant at the 5% and 10% levels, respectively. This indicates that although public opinion does not matter per se, in villages with protest experience prior to village elections, villagers’ preferences significantly correlate with the opinion-policy congruence degree. As Fig. 1(b1) shows, when Protest = 1, PCA-Opinion’s marginal effects are positive on all occasions and are statistically significant, while when Protest = 0, its marginal effects are reduced to be insignificant from zero. In fact, when all other variables are fixed at their mean level and collective protests were present, on average, a unit increase of PCA-Opinion’ corresponds to a opinion-policy congruency level increase of 13 percentage points. Figure 1(b2) illustrates the change in marginal effects of Protest on ACON along the entire range of PCA-Opinion’. Similar to Fig. 1(a2), the marginal effect of Protest is negative when the size of the majority is small and becomes positive and significant after the latter attains a sufficiently high level (PCA-Opinion’ = 3.3). Again, this result suggests that villagers’ assertive strategies cannot enhance the policy-opinion congruency degree until the majority is sufficiently large.

Combining these results, we can infer that as far as rural grassroots elections are concerned, official electoral institutions indeed were reflective of the public opinion of villagers. However, this effect largely reflects the force of the intervention of the higher authorities, including the central government (embodied by the OLVC). For institutions that require huge deliberations and information exchange between villagers and local government, the opinion-policy relationship is not that certain. More importantly, if villagers are able to show their ability to engage in collective action, this can substantially enhance their negotiation power vis-à-vis government officials. However, only when enough villagers attain consensus regarding what institutions they want can their assertive stance add to their cause. Otherwise, such a confrontational strategy is likely to backfire by provoking the local government to respond forcibly to their demands.

As far as other variables are concerned, Regulation has a negative and significant estimated coefficient in most results, except for in Column 1 of Panel B. This suggests that, when all else is equal, the existence of regulations by local government on farmers’ production decisions leads to a lower responsiveness of rule making to public opinion. The policy implication is that when the local government regulates rural agricultural production, the decision-making will be made in a manner that favors the implementation of regulations rather than in a manner favoring the villagers. According to the estimated result, we can infer that, compared to villages without such regulations, villages with regulations will cause the level of congruency of official institutions with the majority preference to drop by 5 percentage points.

Other socioeconomic variables, such as Income, Party, Education, and Town cadre, seem to have no significant influence on the opinion-policy linkage, although the signs of the variables are in the correct direction. The policy implications of these findings are ambiguous. As far as the impact of Party is concerned, for example, on the one hand, a pliable village party committee may suggest the relative ease by which local government can force villagers to be more obedient to its ordinance as assigned through village party branches. On the other hand, however, if village party secretaries play a dominant role as the village “number one” (Zhong and Chen 2002) and are subject to the demands of the local governments, then the local government’s need to manipulate the formation of electoral institutions will decrease. These two mechanisms working together but in opposing directions may eventually account for the lessening significance of the Party variable. Thus, the insignificance of these socioeconomic explanatory variables may not indicate a weak opinion-policy linkage after all but, in fact, may be shown to exert their influence through very complex mechanisms with effects that ultimately cancel each other out. This possibility suggests that future research is needed to examine the effects of socioeconomic variables on the policy-opinion relationship.

Conclusion

Although this research does not tackle the hard issue in opinion-policy-making literature, i.e., does the public opinion of villagers cause the formation of official electoral institutions, our theoretical analyses and empirical findings cast doubt on the conventional wisdom that says under a non-western regime, policy-makers are apathetic to their subjects’ preferences. We find that official electoral institutions, to some extent, fit with public opinion; on the whole, the probability that an electoral institution was implemented increases if more villagers prefer this institution, and in most villages, the official electoral institutions are congruent with the preferences of the vast majority of villagers.

On the other hand, however, the significance of the tight opinion-policy linkage should not be overstated. The seemingly solid opinion-policy linkage can hardly be attributed to the institutionalized participation of peasants or the deliberation between villagers and policy-makers but results more from the directives from above (the OLVC), as well as from the pressures from below (peasants’ collective protests). Hence, it cannot be interpreted as the improvement of democratic governance at any local administrative level.

A more worrisome point is that even if the actual electoral institutions do match up to the preferences of most villagers and they enable villagers to have fair and open elections, it is not that optimistic when we look beyond the sphere of village democratic elections and ask a more general question, such as, will local governments bring about policies that are favored by most villagers?, i.e., those that can encourage more entrepreneurship, protect their property rights (among others land), and provide more social welfare? Unlike the implementation of rural democracy, in which both the central and local officials lose little from villagers’ self-governance because they still monopolize most political and economic resources all the while at all levels, any substantial improvement of policy-making embodied by a greater degree of opinion-policy congruency may likely come at the cost of government officials’ rent-seeking capacity or even their power per se and hence is unlikely to be seen in the foreseeable future. Moreover, the central government is unlikely to impair its local agents’ power foundation to court ordinary villagers unconditionally, even when it faces a great number of people resorting to assertive strategies such as collective appeals and protests to demonstrate their disaffections and demands. In other words, the benevolence of autocrats is limited and contingent. Similarly, the mechanisms posited by our theoretical reasoning concerning the opinion-institution connection in rural elections may simply not work in other spheres of policy-making and governance. Unless China is blessed with a broader and deeper democratization beyond villages, few observers would make a large bet on a real and sound opinion-policy linkage.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Notes

Many theorists believe that democratic governments should respect and reflect the preferences of ordinary citizens (Dahl 1989). On the other hand, however, there are also opponents who claim that the autonomy of policy-making process should be encouraged (Domhoff 2000; Morgenthau 1973). Empirical evidence regarding the opinion-policy relationship also produces mixed views, showing that the true relationship between public opinion and policy is far from being clearly defined (Manza et al. 2002).

Appendix 1 reports the full list of the questions (totaling 21 questions) that the respondents were asked regarding what the ideal electoral institutions ought to be.

For example, Landry et al. (2010) find that villagers who participated in elections are more likely to trust the electoral institutions, therefore pointing to a similar correlation but with an opposite causal relationship.

For a detailed comparison of the differences in electoral institutions in different locations, see O’Brien and Han (2009).

Field observation by the authors in Jiangsu Province, July 2007.

We pay close attention to collective action taken by villagers because individual villagers’ actions could diverge considerably from their preferences, depending on whether they are able to coordinate collective action to act for common interests. As a result, even when villagers share similar preferences for voting rules, a crucial difference between preference and action could exist (e.g., Whiting and Ma 2021).

Field observation by the authors in Heilongjiang Province, December 2010.

As far as the first question is concerned, their answers were either “should be a direct election” or “should be an indirect election”.

We also code the existence of an indirect election with the value of 1; otherwise, the value is 0. The way of coding will not alter our findings, as long as we code the dependent variable consistently across all villages.

As an example, if a direct election is implemented in a village, the dependent variable value should be scored 1 and the explanatory variable value is the proportion of those who believe the ideal electoral institution should be a direct election, for example, 0.85. In another village, if an indirect election is implemented and 40% of villagers believe the ideal type of election should be an indirect election, then the dependent variable should be scored 0 and the explanatory variable value should be 0.4. For multiple-choice survey questions, such as question 5 in Appendix 1, if the dependent variable is scored 1 when in practice the candidates are elected by villagers, then the proportion of villagers who choose answer A, such as 0.25, will be the value of the explanatory variable in that case. Correspondingly, in another village where the candidates are engendered by other means, the dependent variable will be scored 0, and the proportion of villagers who choose answer B, or C, or D, will be the value of the explanatory variable for this particular case.

Here we refer to “most villagers” as a plurality, as opposed to a majority, although in most cases “most villagers” indeed accounted for a majority, and sometimes the absolute majority, of villagers.

It is consistent with intuition that, as the group size in terms of its proportion in the total population increases, say, increasing from 40% to 60%, the importance of the views of this group will correspondingly become more significant.

PCA transforms a number of correlated variables into orthogonal variables, namely, principal components. The first principal component accounts for as much of the variation in the data as possible, and each succeeding component accounts for as much of the remaining variation as possible. For a detailed introduction of the PCA method, see Dunteman (1989). In a recent study, Tsai (2007) used PCA to measure the implementation of village electoral institutions in rural China.

In our calculation, the value of the first Principal Component = 0.22* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′1 + 0.23* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′2 + 0.20* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′3 + 0.23* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′4 + 0.22* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′5 + 0.20* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′6 + 0.22* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′7 + 0.23* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′8 + 0.20* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′9 + 0.22* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′10 + 0.22* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′11 + 0.21* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′12 + 0.21* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′13 + 0.21* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′14 + 0.22* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′15 + 0.218* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′16 + 0.22* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′17 + 0.21* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′18 + 0.23* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′19 + 0.23* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′20 + 0.23* \(\overline{Opinion}\)′21, where \(\overline{Opinion}\) is the standardized form of Opinion’.

References

Acemoglu, D., and J.A. Robinson. 2006. Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cai, Y. 2008. Power structure and regime resilience: Contentious politics in China. British Journal of Political Science 38 (03): 411–432.

Chen, J., and Z. Yang. 2002. Why do people vote in semicompetitive elections in China. Journal of Politics 64 (1): 178–197.

Chen, Jidong, Jennifer Pan, and Yiqing Xu. 2016. Sources of authoritarian responsiveness: A field experiment in China. American Journal of Political Science 60 (2): 383–400.

Dahl, R.A. 1989. Democracy and its critics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Domhoff, W. 2000. Who rules America? Power and politics in the year 2000. Mountain View: Mayfield Publishing Co.

Dunteman, G.H. 1989. Principal components analysis, Sage University papers series. Quantitative applications in the social sciences, no. 07-069. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Geddes, B. 2003. Paradigms and sand castles: Research design in comparative politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Golder, M., and J. Stramski. 2010. Ideological congruence and electoral institutions. American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 90–106.

Goldstone, J., and C. Tilly. 2001. Threat (and opportunity): Popular action and state response in the dynamics of contentious action. In Silence and voice in the study of contentious politics, ed. R.R. Aminzade, J.A. Goldstone, D. McAdam, E.J. Perry, W.H. Sewell Jr., S. Tarrow, and C. Tilley, 179–194. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Haber, S. 2006. Authoritarian government. In The Oxford handbook of political economy, ed. B.R. Weingast and D. Wittman, 693–707. New York: Oxford University Press.

Heurlin, Christopher. 2016. Responsive authoritarianism in China. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Huang, Y. 1995. Administrative monitoring in China. The China Quarterly 143: 828–843.

Jennings, M.K. 1997. Political participation in the Chinese countryside. American Political Science Review 91 (2): 361–372.

Kennedy, J.J., S. Rozelle, and Y. Shi. 2004. Elected leaders and collective land: Farmers’ evaluation of village leaders’ performance in rural China. Journal of Chinese Political Science 9 (1): 1–22.

Landry, Pierre F., Deborah Davis, and Shiru Wang. 2010. Elections in rural China: Competition without parties. Comparative Political Studies 43 (6): 763–790.

Li, L. 2003. The empowering effect of village elections in China. Asian Survey 43 (4): 648–662.

Li, L. 2010. Distrust in government leaders, demand for leadership change, and preference for popular elections in rural China. Political Behavior 33(2): 291–311

Luo, R., L. Zhang, J. Huang, and S. Rozelle. 2007. Elections, fiscal reform and public goods provision in rural China. Journal of Comparative Economics 35: 583–611.

Manion, M. 1996. The electoral connection in the Chinese countryside. American Political Science Review 90 (4): 736–748.

Manion, M. 2006. Democracy, community, trust: The impact of elections in rural China. Comparative Political Studies 39 (3): 301–324.

Manza, J., F. Cook, and B. Page. 2002. Navigating public opinion: Polls, policy, and the future of American democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, W., S. White, and P. Heywood. 1998. Values and political change in Postcommunist Europe. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Morgenthau, H. 1973. Politics among nations: The struggle for power. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

O’Brien, K.J. 2001. Villagers, elections, and citizenship in contemporary China. Modern China 27 (4): 407–435.

O’Brien, K.J., and R. Han. 2009. Path to democracy? Assessing village elections in China. Journal of Contemporary China 18 (60): 359–378.

O’Brien, K.J., and L. Li. 2006. Rightful resistances in rural China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ofosu, GK. 2019. Do fairer elections increase the responsiveness of politicians. American Political Science Review 113(4): 963–979.

Olson, M. 1993. Dictatorship, democracy, and development. American Political Science Review v87 (n3): p567(10).

Papke, L.E., and J.M. Wooldridge. 1996. Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401(K) plan participation rates. Journal of Applied Econometrics 11 (6): 619–632.

Przeworski, A. 1986. Problems in the study of transitions to democracy. In Transitions from authoritarian rule: Comparative perspectives, ed. G. O’Donnell, P.C. Schmitter, and A. Whitehead, 47–63. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Shi, T. 1997. Political participation in Beijing. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Shi, T. 1999. Village committee elections in China: Institutionalist tactics for democracy. World Politics 51 (3): 385–412.

Su, F., T. Ran, X. Sun, and M. Liu. 2011. Clans, electoral procedures and voter turnout: Evidence from villagers’ committee elections in transitional China. Political Studies 59 (2): 432–457.

Tang, W. 2005. Public opinion and political change in China. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Tsai, L.L. 2007. Solidary groups, informal accountability, and local public goods provision in rural China. American Political Science Review 101 (02): 355–372.

Weber, R.E., and W.R. Shaffer. 1972. Public opinion and American state policy-making. Midwest Journal of Political Science 16 (4): 683–699.

Whiting, Susan H., and Xiao Ma. 2021. Validating vignette designs with real-world data: A study of legal mobilization in response to land grievances in rural China. The China Quarterly 246: 586–601.

Wilezien, C., and S.N. Soroka. 2007. The relationship between public opinion and policy. In Oxford handbook of political behavior, ed. R.J. Dalton and H.-D. Klingemann, 799–817.

Wintrobe, R. 2000. The political economy of dictatorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wyman, M. 1997. Public opinion in postcommunist Russia. London: Macmillan Press.

Zhang, Q., M. Liu, and W. Shan. 2006. Government regulations, legal-soft-constraint and rural grassroots democracy in China. In China’s rural economy after WTO, ed. S. Song and A. Chen, 336–357. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company.

Zhong, Y., and J. Chen. 2002. To vote or not to vote: An analysis of peasants’ participation in Chinese village elections. Comparative Political Studies 35 (6): 686–712.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors are involved in theory construction, case analysis and article writing. All author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Survey questions regarding the ideal election institutions favored by villagers

1. Do you think village committee leaders should be a directly elected by villagers or by their representatives? | |

2. In your opinion, what should be the optimal voting method in an election? A) one-villager-one-ballot; B) one-villager representative-one-ballot; C) one-household-one-ballot | |

3. Do you think secret ballots should be used so that other people do not know who you are voting for when you mark your ballot? | |

4. Do you think there should be more candidates than offices? | |

5. In your opinion, what is the optimal way to engender the candidates in the primary election? A) elected by villagers; B) recommended by villagers; C) recommend themselves as candidates; D) others | |

6. In your opinion, what is the optimal way to determine which candidates are qualified to run for the position of chairman of the village committee? A) depends on the results of the primary election; B) depends on the appointment of local government, village party committee or incumbent village cadres; C) others | |

7. Do you think the qualification of candidates should depend on the approval of local government? | |

8. In your opinion, what is the minimum voter turnout of villagers necessary to guarantee the validity of the election result? | |

9. In the election, what is the minimum percentage of total ballots the candidate needs to win? A) > 50% of all qualified voters; B) > 50% of voters who turn out to vote; C) no minimum requirement is necessary, as long as one receives the most votes. | |

10. In your opinion, should electoral campaigns be allowed? | |

11. Do you believe candidates should be allowed to give campaign speeches? | |

12. Do you think the village party committee election (VPCE) should be held before the village committee election (VCE), or should the VPCE be held after the VCE? | |

13. Do you think the village party secretary should be allowed to run for the position of chairman of the village committee? | |

14. Do you think the village party secretary should be allowed to be a member of the village election committee? | |

15. If a resident does not have registered permanent residence in the village but has lived in the village for more than 3 years, do you think he or she should be given the right to vote in a village election? | |

16. What about a villager who has a registered permanent residence in the village but does not actually live there? Do you think he or she should be allowed to vote in village elections? | |

17. Do you think proxy voting should be allowed? | |

18. Do you think villagers should be allowed to vote through mail? | |

19. In your opinion, what is the optimal way to select members of the village election committee? A) appointed by local government, by village party committee, or by incumbent village cadres; B) elected or recommended by villagers, household representatives, or villager representatives. | |

20. Do you think the local government should send officials to the village to supervise the election process? | |

21. Do you think the election results should be announced immediately after the polls close? |

Appendix 2

Sampling strategy

The sampling strategy is as follows: first, one province was randomly selected from each of China’s 6 large regions. These regions are Shaanxi (northwest), Sichuan (southwest), Hebei (north), Jilin (northeast), Jiangsu (east) and Fujian (southeast). Second, five counties in each province were identified by dividing all counties within the province into five quintiles based on their income levels and then selecting one county per quintile. Next, two townships within each county and two villages within each township were randomly selected. Finally, in each village, 16-18 households were randomly selected to receive the survey.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Liu, M. Do rural electoral institutions reflect public opinion in China? Evidence from village elections. ARPE 1, 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44216-022-00003-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44216-022-00003-9