Abstract

Impact assessments are increasingly employed and debated as instruments for mitigating the fundamental rights risks associated with artificial intelligence, platforms and personal data processing. However, before their adoption in connection with technology and fundamental rights, impact assessments have been used for decades to mitigate large undertakings’ environmental and social impacts. An impact assessment is a process for collecting information to identify a future action’s effects and mitigate its unwanted effects. This article proposes that impact assessments represent a distinct legal design pattern with core elements that can be replicated in new legal contexts requiring ex-ante identification and mitigation of foreseeable risks. The tensions between diverging interests, temporality, epistemics and economics characterise this legal design pattern. The impact assessment process seeks to resolve these tensions by enabling translation between the regulator, the executor of the planned action and the stakeholders impacted by it. Awareness of the underlying patterns allows the lawmaker or the regulator to learn across diverse impact assessment models. Design pattern thinking advances research both on law and regulation by uncovering the tensions underling the design solution, as well as pattern interaction between legally mandated impact assessments and those representing other regulatory instruments. Finally, the approach raises awareness of the instrument’s shortcomings, including spheres where relying on complementary legal design patterns, such as precautionary principle, is more justified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 A Trend Towards Fundamental Rights-Based Impact Assessments for AI

In Europe, impact assessments for artificial intelligence (AI) have been brought forward as a desirable regulatory tool to contain unwanted risks associated with the technology ex-ante (HLEG, 2019, p. 15; CoE & CAHAI, 2020, 2021; CoE & Yeung, 2019). The inclusion of fundamental rights impact assessment (FRIA) into the Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA), has been subject to a considerable debate throughout the act’s the legislative process. The FRIA obligation was supported by the European Parliament, academics and the civil society (FRA, 2021; EDRi, 2021, EDRi et al. 2023; AIA, EP, 2023; Brussels Privacy Hub, 2023), and resisted by technology companies (DIGITALEUROPE, 2023; Konopczyński, 2023; Waem & Demircan, 2023). Why has a fundamental rights impact assessment become a prominent tool for regulating AI?

The concept of an assessment denotes the “action or an instance of making a judgement about something” (Merriam Webster, n.d). Impact assessment (IA) can be defined as “a structured process for considering the implications, for people and their environment, of proposed actions while there is still an opportunity to modify (or even, if appropriate, abandon) the proposals. It is applied at all levels of decision-making, from policies to specific projects” (IAIA n.d.). Alternatively, impact assessment can refer to “a study of what the harmful effects of a planned action would be on a particular place, activity, or group of people, or a report in which the results of such a study are given” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d. a). The study is used to inform a decision-making process (Kloza et al., 2017).

The term impact assessment is often used synonymously with the concept of risk assessment, which represents “the process of examining the risks involved in a planned activity” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d. b). Many assessment tools refer both to risks and impacts (Art. 35 GDPR; Arts. 33–34 DSA; ISO/IEC, 2023). Impact can be defined as “a strong effect or impression” or the “(the force of) one object etc hitting against another” Cambridge Dictionary, n.d. a). Thus, impact implies the presence of causality and qualitatively significant consequences. The concept of a risk refers to “the possibility of something bad happening” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.c). It can be understood to refer to the probability of an unwanted impact as well as to the impact’s severity (Art. 3 (1a) AIA, (2024), see also NIST, (2023), p. 4). Against this background, as an instrument an IA is inherently future-oriented, geared towards “the identification of future consequences of a current or proposed action” (Clarke, 2009, p. 125). This article focuses on project-based impact assessments.

The proposals for FRIA for AI draw from multiple impact assessment practices. Ideas for fundamental rights impact assessments evolved, on the one hand, from human rights impact assessments (De Beco, 2009; The Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2020). This IA type is a tool for fulfilling businesses’ human rights due diligence obligations (Principles 12,15,17, UN, 2011; Esteves et al., 2012; Kemp & Vanclay, 2013), which will also legally bind large EU corporations, as the parliament accepted the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (EP 2024) proposal. The FRIA for AI can be seen to build upon IAs that, prima facie, emphasise individual rights, such privacy impact assessment (PIA) or data protection impact assessment (DPIA) (CoE & Yeung, 2019; Sec 208, E-Government Act of 2002; Clarke, 2009; Wright & de Hert, 2012; Australian Government, n.d.; ISO/IEC, 2023; Arts. 35–36 GDPR). The discourse also draws from algorithmic impact assessments, which have been developed by a wide range of actors, including research communities for algorithmic fairness and public agencies, NGOs, private companies and standard-setting organizations (See Reisman et al., 2018; Government of Canada, n.d.; CIO, n.d.; Ada Lovelace Institute, 2022; NIST, 2023; Stahl et al., 2023). Human rights are increasingly deemed a more robust framework to govern AI than principles of algorithmic fairness (See McGregor et al., 2019; Yeung et al., 2020). For example, the High-Level Expert Group sought to systematise ethical principles for AI under the EU fundamental rights framework. Thus, besides explicit references to fundamental rights, its proposal for a Trustworthy AI Assessment list covered areas more closely associated with AI ethics, such as transparency and explainability (HLEG, 2019). Similar hybrids between fundamental rights and algorithmic impact assessments and their sub-processes have also been proposed by other actors (Mantelero, 2018; Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, 2022; Fujitsu, 2022; ECNL, 2023; See also Stahl et al., 2023, p. 12,810).

Coupling algorithmic assessments with human and fundamental rights and mandating their execution by law pulls the instrument out of the realm of self-regulation and soft law (Yeung et al., 2020). Ensuring high level of protection of health, safety and AI systems fundamental rights is one of the goals of the AIA, alongside with the improving the functioning of the internal market, promoting the uptake of human-centric and trustworthy AI and supporting innovation (Art. 1 (1) AIA, 2024). The AIA prohibits certain AI uses that contradict fundamental rights (Art. 5, rec 15 AIA, 2024). Furthermore, it mandates a conformity assessment procedure for AI high-risk AI systems, which involves compliance measures on quality and risk management, data governance, technical documentation, record keeping, transparency, human oversight and cybersecurity of the system (Arts. 6, 8–15, 17, 43, Annexes III, VI, VII AIA, 2024). In addition, European Parliament proposed a detailed FRIA obligation to deployers of high-risk AI systems (Art. 29a AIA, EP, 2023). However, the compromise text featured a considerably narrower obligation, which most importantly, was applicable only to public sector deployers (Art. 29a AIA, 2024).

In addition to an explicit FRIA, the final AIA features three provisions that require AI system providers to assess the system’s fundamental rights risks of impacts. First, the risk management obligations include the identification, analysis of the known and reasonably foreseeable risks high risks that the AI system can pose to health, safety and fundamental rights when used in accordance with its intended purpose, as well as estimation of risks that may emerge in connection with reasonably foreseeable misuse as well as measures to eliminate, mitigate and control the identified risks (Art. 9 2(a)–(b), 4 (a–b) AIA, 2024). Second, the compliance with the data governance obligations require an examination of training, validation and testing data in view of possible biases that are likely to affect the health and safety of persons, negatively impact fundamental rights or lead to discrimination prohibited under Union law, especially where data outputs influence inputs for future operations (Art. 10 (2) (f) AIA, 2024). Third, providers of general purpose AI models with systemic risk are obliged evaluate and test the model with a view of mitigating systemic risks as well as assess and mitigate risks arising during the life-cycle of the model at the Union level (Art. 52d AIA, 2024). The concept of systemic risk includes significant on actual or reasonably foreseeable negative effects on fundamental rights that can be propagated at a scale across the value chain (Art. 3 (44d) AIA, 2024).

Parallel to the AIA’s legislative process, the Council of Europe proposed a Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence, Human Rights, Democracy and The Rule of Law Proposal (CoE, 2023a, b). Whereas the initial draft proposed an risk and impact assessments for both providers and users of AI (Art. 24 CoE, 2023a, Art. 15 CoE 2023b), the scope of entire convention, which still includes an IA provision, was subsequently narrowed to public authorities (Arts. 3 & 16, CoE, 2024).

Debate on legally mandated fundamental rights impact assessments for AI and the recent legislative activity did not emerge in a vacuum, but reflects a broader legislative trend (Nahmias & Perel, 2021). The European Union has pioneered an expressly fundamental rights-driven, risk-based approach to regulating AI and data. An obligation to carry out IAs for identifying solutions’ risks on fundamental rights ex-ante was first introduced by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which mandates ia DPIAa for processing that is likely to result in a high risk to rights and freedoms of natural persons (Arts. 35–36; Art 29 DPWP, 2017). The DPIA is a successor of an earlier requirement to examine processing operations that present risks to data subject’s rights and freedoms prior the start thereof (Art. 20 Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC).

The AIA’s rules on general purpose AI models with systemic risks appear to have been influenced by the instrument adopted in the Digital Services Act (DSA). The DSA obliged providers of very large platforms to carry out risk assessments and risk mitigation measures, which focus on systemic risks, any actual or foreseeable adverse effects for the exercise of fundamental rights, as well as several risks closely associated with online platforms, such as involving dissemination of illegal content and negative effect on civic discourse, electoral processes and public security (rec 90; Arts 34). The instrument also involves detailed measures for risk mitigation (Art. 35 DSA).

This trend toward adopting impact assessments can also be observed in the US (Nahmias & Perel, 2021). In the context of transatlantic cooperation, the EU-US Trade and Technology Council acknowledges the role of human rights and effective risk management and assessment frameworks in the governance of trustworthy AI (TTC, 2022). Also, the US is promoting national, risk-based initiatives to regulate AI. For example, the Algorithmic Accountability Act of 2022 would allow the Federal Trade Commission to require impact assessments for algorithmic decision systems and augmented critical decision processes. Although not expressly referring to fundamental rights, the Act gives account to impacts on non-discrimination, consumer privacy, security and safety and principles of AI ethics (Sec. 4; for a comparison with the AI Act, see Mökander et al., 2022) Furthermore, also the bill for the American Data Privacy and Protection Act includes an Algorithm impact assessment that considers risks of harms to an individual or groups of individuals (Sec. 207). In addition, several state-level proposals to regulate AI in the US feature impact assessments to mitigate discrimination (Davis & Strauss, 2024).

1.2 The Diversity of Impact Assessment Models

Before being employed in connection with human rights (De Beco, 2009) or promoted for mitigating risks associated with AI (Kaminski & Malgieri, 2020; Mantelero, 2018; Raji et al., 2020; Wieringa, 2020) or other emergent, potentially patentable technologies (Pila, 2020), impact assessments have been used decades to identify large undertakings’ social and environmental impacts (See Burdge, 1991; Vanclay, 2003; Esteves et al., 2012). Environmental Impact Statements were first required by the US in the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969. Since then, the instrument has been part of the environmental law of numerous countries. In the EU, the Environmental Impact Assessment Directive 2011/92/EU, as amended by 2014/52/EU (later, EIAD), requires the assessment to be carried out in connection with projects such as nuclear power stations and express roads, and allows member states to require them for other development projects with significant impact on environmental dimensions. Social impact assessments, as the name suggests, focus on charting the social implications of a planned project or an activity. NEPA accounted for the social impacts of projects subject to environmental impact assessment. However, it took decades before their assessment was integrated into the accompanying administrative guidelines of EIA and was, in some states, mandated by law (Burdge & Vanclay, 1996). Social impact assessments remain predominantly voluntary instruments. However, the instrument also evolved to consider human rights (Kemp & Vanclay, 2013; Vanclay, 2003) and can be deemed a precursor of independent human rights impact assessments (De Beco, 2009).

Technology is often developed to mitigate risks, yet regularly creates another set of dangers. The degree of risk that a specific technology entails represents a design choice based on the prevalent cultural values (Luusua & Ylipulli, 2020). Respectively, besides algorithmic IA, several other types of impact assessments have been deployed to mitigate technological risks. The DPIA evolved from PIAs, that were developed by an international community of public officials, regulators and academics (Clarke, 2009) as well as their voluntary adoption by the private sector and later by public authorities (Binns, 2017). PIA is a tool for evaluating and mitigating privacy and data protection risks associated with information systems. Unlike the legally mandated DPIA, the PIA methodologies extend beyond “mere legal compliance” to exploration of what constitutes risks and how to make informed decisions between competing values (Raab, 2020, p. 7). Surveillance IA takes this exploratory approach further, with the aim of identifying social and collective impacts of surveillance, that rights-based instruments, such as DPIA, cannot capture (Raab, 2020; Wright & Raab, 2012). In the context of research and development, ethical impact assessments are of importance (Wright, 2011), and are required by research funding agencies such as European Commission (EC, 2021a).

Risk assessments serve as tools to organizational risk management (See also Art. 9 AIA, 2024), which represents a wider array of “coordinated activities to direct and control an organization with regard to risk” (ISO, 2018). In that context, they represent a process of risk identification, analysis and evaluation and can be carried out deploying numerous methods (IEC, 2019). Companies may also carry out risk and impact assessments to comply with due diligence obligations (see DSA Chapter III; Principles 18–21 UN, 2011; rec 30, Arts. 2, 30 CRDDD, EP, 2024). In a traditional commercial context, due diligence should be followed in “any situation where it is likely to face commercial, financial or legal risks that could lead to liability and which should reasonably be avoided”(Muchlinski, 2014, n. 32). In addition, due diligence may refer to a standard of conduct (Bonnitcha & McCorquodale, 2017). Due diligence have gradually expanded also to include corporate responsibility for human rights impacts. To gain protection against legal claims, companies should demonstrate that they took every reasonable step to avoid involvement with an alleged human rights abuse (UN, 2011, p. 19), this involves assessing the impacts, integrating and acting upon findings, monitoring responses, and communicating how they addressed the impacts (Principles 17 UN, 2011).

Besides using impact assessments to evaluate the implications of individual projects or products, or for the purposes of risk management and compliance, the tool can be employed as a preparatory tool for law and policymaking. Regulatory impact assessments, including legislative impact assessments, represent instruments for charting and reviewing the effects of initiatives for regulations, laws or policies deployed to support evidence-based policymaking (OECD, 2020). Subcategories of regulatory impact or risk assessments are Strategic Environmental Impact Assessments for plans and programmes (Directive 2001/42/EC) and technological impact assessment, which aim to support policymaking by reviewing foreseeable “impacts of technological change and applications” (Rip, 2015, p. 125). Some regulatory impact assessments aim at evaluating a very broad range of impacts—for example, sustainability impact assessments look into economic, social, environmental impacts (OECD, 2021).

Overall, impact assessments are adopted in numerous legal and regulatory fields. In this paper, I will focus on project-based impact assessments (PBIA) and argue that they represent a distinct legal design pattern. In Sect. 2, I will introduce the concept of legal design patterns and a method for discovering the procedural pattern language of impact assessments. I make a case for accounting also for PBIAs that are not mandated by law, hereafter referred to as regulation-based impact assessments, while exploring the instruments’ status as a legal design pattern. Section 3 will qualify impact assessments as regulatory instruments through the lens of regulatory theories. It provides a foundation for in-depth qualification of impact assessments as legal design patterns (See Alexander, 1973; Koulu et al., 2021) in Sect. 4 and the inherent tensions that all impact assessments aim to solve. Section 5 breaks down the procedural pattern language of project-based impact assessments (See Alexander, 1979; Koulu et al., 2021) and the significance of each stage in the light of resolving inherent tensions associated with them. Section 6 provides conclusions on the value of the legal design pattern lens for the study of impact assessments for AI and identifies avenues for further research.

2 Design Pattern Lens on Impact Assessment

2.1 The Pattern Language

Impact assessments vary in their scope, scale and conditions of the application, parties involved, whether they are mandated by law or volunteered (CoE & Yeung, 2019). Despite the vast diversity of instruments, they represent an intuitive solution to contexts where it is crucial to evaluate future impacts of activity and adopt a course of action most favourable for the values at stake. Could impact assessments represent a “timeless way” (Alexander, 1979; Alexander et al., 1977) to approach the problem of mitigating future risks? The simultaneous heterogeneity and prevalence of impact assessments suggest that we are dealing with a reusable problem-solving model (see Gamma et al., 1993). Being successfully adopted in different fields throughout several decades could qualify impact assessments as a legal design pattern (Koulu et al., 2021).

Christopher Alexander developed a concept of a design pattern in the context of architecture and urban planning. He proposed that there are archetypal, recurring solutions to present on different levels of urban planning—small-scale patterns for construction, mid-level patterns for buildings, and large-scale patterns for a town or community (Alexander et al., 1977). A timeless pattern in architecture can be qualified as:

At the core of all successful acts of building and at the core of all successful processes of growth, even though there are a million different versions of these acts and processes, there is one fundamental invariant feature which is responsible for their success. Although this way has taken on a thousand different forms at different times, in different places, still there is an unavoidable, invariant core to all of them (Alexander, 1979, p. 8)

Thus, design solutions can be abstracted to their “true invariant” […] a property common to all possible ways of solving a stated problem” (Alexander, 1979, xiv). According to Alexander, thriving cities are constructed through a network of interrelated design patterns, referred to as a pattern language. He identified 253 timeless solutions concerning topics such as neighbourhood boundaries, access to water, health centres, small public spaces, dancing in the street, bus stops, roof gardens, couple’s realm and fruit trees (Alexander et al., 1977).

How do wholesome solutions to urban planning relate to impact assessments for AI? Over time, design pattern thinking has been adopted in decreasingly material realms—first in software and human-computer interaction(See Gamma et al., 1993; Borchers, 2000; Dearden & Finlay, 2006; Mayvan et al., 2017) with some exploration on design patterns for legally compliant technologies (see Dickhaut et al., 2022; Hoffmann et al., 2015). More recently, the design pattern lens has been introduced to legal research (Koulu et al., 2021; Koulu & Pohle, 2024). The value of Alexander’s approach is in uncovering and communicating abstract yet reusable solutions and architectures formed through interrelationships of such patterns (Koulu et al., 2021). The legal design pattern lens allows for the identification and reuse of solutions present in different branches of law, resulting in “improving law’s problem-solving and self-reflecting capabilities” (Koulu et al., 2021, p. 3). Despite the subjectivity of pattern recognition, legal design patterns are expected to reflect deeper values underscoring the legal system (ibid., p. 13). Theoretically, the legal design patterns research draws from Niklas Luhmann’s systems theory, which presumes that social systems, such as legal and economic systems, are autopoietic, i.e. functionally differentiated, self-reproducing and operationally closed off from each other (Baraldi et al., 2021a2021b; Luhmann, 2013). They may observe one another only to the extent that this is relevant for their self-reproduction. This process is called structural coupling: communications between systems that lead to their self-irritation. These disturbances initiate information processing within the system, leading to in-system structural changes (Baraldi et al., 2021a; Luhmann, 2013). Legal design patterns are proposed to enable structural coupling through translation between distinct systems, such as law and computer science (Koulu et al., 2021, p. 4; Koulu & Pohle, 2024) or their subsystems, such as between distinct legal doctrines. Legal design patterns may thus offer irritations that force the system “to develop conceptual innovations by its own, internal, path-dependent evolutionary logic” (Teubner, 2009, p.4).

The design pattern approach to can uncover the structural features of effective legal solutions, which may facilitate the digitalization and automation of law (Pöysti, 2024). Digitalization and automation of law require “technology-conscious” legal drafting, with awareness of which normative values, such as the rule of law, must shape the automated law and how to formalize them into code (Schartum, 2020; See also Zalnieriute, 2020; Pöysti, 2023). Automated decision-making also requires procedural safeguards to protect the key legal values, such as fundamental rights (Pöysti, 2023; Zalnieriute, 2020). The lack of standardisation is one of the obstacles to the digitalization of IAs (IAIA, 2021) The legal design approach (Koulu et al., 2021) could help to identify and standardise different modules of an impact assessment, which could also and unify its use across different domains of law, improving the overall coherence of the legal system and regulatory systems adjacent to the use of the instrument. Identifying a structurally uniform core of a legal design pattern can facilitate the digitalization of law, legal processes as well as processes of risk management (See Pöysti, 2024).

2.2 Pattern Discovery

Focusing on the project-based impact assessments, I hypothesise that impact assessments represent a legal design pattern (Koulu et al., 2021; Koulu & Pohle, 2024). When mandated by law, they belong to a subcategory of procedural legal design patterns titled “moving protection upstream”, which aims at extending the scope of legal protection, whether in their social, temporal, spatial or material dimensions, so that extended scope allows for easier detection and prevention of infringements” (Koulu et al., 2021, p. 16). However, to qualify as a legal design pattern, the solution brought by an PBIA must be articulated in a precise, abstract and temporally detached manner (Ibid). To facilitate the ongoing discourse and experimentation on AI impact assessments, I proceed to mine (Koulu et al., 2021; Koulu & Pohle, 2024) the existing IA instruments to uncover the essential elements of a legal design pattern: “name of the pattern, the design solution it puts forward, description of the problem and the conflicting forces at play, and the context and conditions for the patterns applicability” (Koulu et al., 2021, p. 24). I will use this framework to describe impact assessments in Sect. 4. In Sect. 5, I proceed to identify the procedural pattern language inherent to impact assessments (See Alexander, 1979; Koulu et al., 2021).

To this end, I “mine” (Koulu et al., 2021, p. 13) the known examples of impact assessments, emergent proposals for new models, and their meta-studies to identify the essential design elements of the impact assessment process. As source material, I rely primarily on the examples of legally mandated impact assessments and associated practices (Environmental law, Data Protection-by Design and Data Protection Impact Assessment) and impact assessments recently passed into effect (DSA), or proposed (CoE, 2024; AIA, 2024). For the reasons detailed in the subsequent sections, I will rely on the literature on regulation to uncover the tensions inherent to the PBIA as a legal design pattern. On this basis, I will also account for the designs of IAs that widely recognized that are not necessarily legally mandated (PIA, Social Impact Assessment, Human Rights Impact Assessment, Surveillance Impact Assessment.) Since the literature and the field of algorithmic impact assessments is emergent and highly heterogeneous, this study relies on several examples and meta-studies for algorithmic impact assessments (See Mantelero, 2018; Moss et al., 2021; Stahl et al., 2023).

The process of discovering the pattern language of PBIAs in the Sect. 5 bears some similarities to the methodology Moss et al. (2021), where the essential procedural sub-patterns of impact assessments are inducted from existing and emerging impact assessment models. However, the inquiry into the known impact assessment models does not represent a systematic literature review of all available impact and risk assessment tools or algorithmic impact assessment models (See Iwaya et al., 2024; Stahl et al., 2023; Wairimu et al., 2024) or a thorough comparison of existing IA models (Cf. Moss et al., 2021). The methodological choice is deliberate. Alexander rejected mechanical methods in the discovery of timeless patterns (1979, pp. 12–14). Despite an engagement in a systematic pattern “mining,” pattern discovery is described as a subjective, intuitive process (Alexander, 1979). It may even involve an emotional reaction to a pattern which is of a good fit to solve the problem at hand (ibid. p. 255).

Whether and how emotions can guide the discovery of legal design patterns is a topic for further research. In this study, I relied on four signposts to control against excessive subjectivity the pattern discovery from the literature on impact assessments and regulation. First, our inductive pattern mining process was informed by Alexaner’s definition of a procedural design pattern, as “operational and precise. It is not merely a vague idea or a class of processes which we can understand: it is concrete enough and specific enough so that it functions practically […] it is a method or a discipline, which teaches precisely what we have to do to make our buildings live” (Alexander, 1979, p. 12). Also “these processes can be made so explicit, and so clear, that any group of people can make use of them” (ibid, p. 10). The audience of the pattern is the lawmaker, regulator or an academic interested in drafting or developing an PBIA. As a consequence, I do not focus on practical challenges of PBIA practitioners experience in the description of the pattern language in Sect. 5. Second, I assume that an ideal pattern is simple and abstract: “it shows us what we know already, only daren’t to admit because it seems so childish, and so primitive” (Alexander, 1979, p. 13). For this reason, the study holds back from engaging in several debates and discourses surrounding the design of specific PBIA models, as the absence of a consensus suggests the absence of an ideal pattern.

Third, I assume that legal design pattern is simultaneously descriptive and normative (Koulu et al., 2021, p. 24; Koulu & Pohle, 2023; see Alexander et al., 1977, p. xv; Winner, 1980). The discovery process requires observing “solutions as they are repeated in legal structures” in abstract and detaching from legal, doctrinal categories. The process presupposes oscillation between the internal and external perspectives on law (Koulu et al., 2021, p. 15). The PBIAs mined for the study aim at the fulfilment of a wide range of normative goals defined both by law-makers and other regulatory actors. As a consequence, there is no single normative goal or value to frame the pattern discovery (cf. Pöysti, 2023). To discover the ideal PBIA process in the context of the normative heterogeneity of PBIAs, I used regulatory theories (Sect. 3) to identify the tensions inherent to the PBIA as a design pattern (Sect. 4). The discovered tensions were then used to assess, which elements the PBIA process were part of the pattern language (Sect. 5). In other words, the element was deemed as essential to the PBIA when it solved one or more tensions associated with PBIAs.

Finally, the pattern discovery process can be undertaken collectively (Dearden & Finlay, 2006; Koulu & Pohle, 2024), which enhances the qualitative intersubjectivity of the pattern discovery. Our pattern mining for impact assessments benefited from the insights and comments of the participants at the June 2023 Legal Design Pattern workshop in Helsinki (see Koulu & Pohle, 2024). The workshop and interaction with the other scholars in the community helped to distinguish impact assessments from other patterns, such as precautionary principle (Pöysti, 2023) and loops (Pohle, forthcoming). It also confirmed the existence of a two-layered impact assessment structure within the GDPR (Art. 24–25 and Art. 34–35). Nevertheless, the author recognizes that the pattern discovery process remains, in part, subjective also because it entails making sense of PBIAs developed in the context of other autopoietic social systems (See Baraldi et al., 2021a2021b; Luhmann, 2013). As a consequence, their review is shaped by the legal background of the author, which may overlook design solutions that are of essence in the context of the social system they were developed in.

2.3 The Relevance of Regulation-Based Impact Assessments

However, not only are impact assessments adopted in environmental law, data protection law and technology regulation, but the tool is also used without any judicial obligation to undertake an impact assessment process. Although not mandated by law, such impact assessments represent regulation in its broad definition—“all forms of social control, whether intentional or not, and whether imposed by the state or not” (Morgan & Yeung, 2007, pp. 2–3). Regulation is a highly interdisciplinary field of study, drawing from several social science fields (Morgan & Yeung, 2007; Baldwin et al., 2012). Although the design pattern lens has not been applied to regulation before, introducing this perspective to study impact assessments appears frictionless, given the fields’ tradition to investigate the genesis, effect and success of regulatory interventions and conceptual analysis of regulatory instruments. Regulatory scholars even echo the language of design patterns (Alexander, 1979; Alexander et al., 1977). First, regulation theories describe the “typical patterns of interaction between regulatory actors “(Morgan & Yeung, 2007, p. 16). Second, Black proposes in her theory of regulation that “through an integration of a theoretical analysis of the nature of the rules and an empirical analysis of the use of rules and their formation, a model of rule-making can be developed which seeks to explain how in fact rules and used and to suggest the ways they could be used” (Black, 1997, p. 250). Black further suggests that regulation and rules may be studied in one context and generalised into another (Black, 1997). The design pattern approach supports this ambition to abstract recurring solutions that are simultaneously descriptive and prescriptive (Koulu et al., 2021).

Regulators engage actively in the selection and design of the norms in the given, dynamic, historically, socially and politically contingent context. In the selection of norms, both the design of the regulatory system in which the regulator operates and the design of the norms themselves are essential. The regulatory system sets a blueprint for rules that are not only lawful, but also appropriate and acceptable (Black, 1997, p. 247). The regulatory system features hierarchies of interrelated norms, which can be seen to form a pattern language of their own. Higher-order patterns (the regulator’s freedom to operate) shape the lower-order patterns (regulations). Regulatory tools also interact with one another (See Black & Baldwin, 2010). For example, the theory of responsive law proposes a regulatory design of “contingently escalating responses” forming a hierarchy of enforcement instruments (Braithwaite, 1982, p. 161). In their theory on “smart regulation”, Gunningham et al. (1998a) reflect on regulatory design principles and identify complementary and counterproductive combinations of regulatory instruments.

Recognising that research on legal design patterns is exploratory, I view it as too insular to account for only judicial instruments in the discovery of legal design patterns. Regulation-based impact assessments often predate legally mandated forms of the instrument, thus revealing the genesis of a legal design pattern (see Binns, 2017). Giving account to regulatory instruments uncovers the processes of problem identification in law (See Koulu & Pohle, 2024). Furthermore, regulation-based impact assessments refine, expand and iterate legally mandated impact assessment processes, testing their usefulness in novel contexts. Expanding the scope of the exploratory process allows for a closer inspection of “law’s self-reproduction” and reactivity to social needs (See Koulu et al., 2021, p. 25).

3 Impact Assessments as Regulatory Instruments

Impact assessments have been characterised as collaborative governance, often involving regulatory cooperation between public and private sectors (Kaminski & Malgieri, 2021; see also Selbst, 2021). Impact assessments typically involve a degree of self-regulation. Self-regulation is perceived as the polar opposite of the “command and control” regulatory approaches that focus on uniform, enforceable rules. Nevertheless, most regulatory approaches have an element of both (Sinclair, 1997).

Impact assessments where a company, an industry or a non-governmental or private institution, such a standard setting organization, determines the values at stake, methods and oversight represent self-regulation (See Clarke, 2019). An example of such an instrument would be the predecessor of data protection impact assessment (Art. 34–35 GDPR), privacy impact assessment (Binns, 2017; ISO/IEC, 2023; Cf Clarke, 2009) and an algorithmic impact assessment relying only on values determined by AI ethics. Others, such as human rights impact assessments, social impact assessments or algorithmic impact assessments referencing human and fundamental rights, rely, at least to a degree, on soft law.

From the perspective of regulatory theory, legally mandated impact assessment practices (Directive 2011/92/EU; Art. 35–36 GDPR, Art. 24 DSA) represent enforced self-regulation. Under this approach, it is presumed efficient to delegate “some or all legislative, executive or regulatory functions” to a private actor (Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992, p.103). The company is expected to be in the best position to identify and control the relevant risks (Haines, 2017). It is thus tasked to determine the rules that apply to its operating context. For example, the power to determine the details of the IA process may be delegated to standard setting organizations which would act as co-regulators though delegation of powers (See Clarke, 2019; Art. 40, AI Act, 2024). The regulator’s role is to approve the rules, ideally after hearing stakeholders and the greater public, and to ensure, using audits, that it the co-regulator complies with the rules it proposed (Braithwaite, 1982). Such subcontracting of regulatory functions is introduced in the broader context of responsive law, wherein regulatory interventions escalate from dialogue to sanctions (Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992).

Mandatory impact assessments can also be seen as a form of meta-regulation (Binns, 2017). Acknowledging that not all companies are champions of corporate responsibility, Parker proposes that the law may foster companies’ capacity to self-regulate and hold them accountable for their self-regulatory activity. This aim may be reached by regulating the process of self-regulation (2002), such as carrying out an impact assessment and establishing rules on liability and enforcement against non-compliance. Overall, impact assessments can be viewed to represent proceduralization: “a form of replacing a substantive decision by a legally established process of consultation, participation or balancing conflicting interests“ (Ladeur, 1996, p.3). From the perspective of systems theory (Luhmann, 2013; Teubner, 1993), both law and the social system it intends to regulate are self-reproducing and self-referential and therefore fail to communicate with one another. Consequently, law fails to regulate other systems through hierarchical, imposing rules because they fail to enable the structural coupling between two or more systems (Teubner, 1985). A more reflexive approach to law favours a high degree of self-regulation while enabling reciprocal observations between systems, for example, through procedural norms (Teubner, 1993) and “expose[ing] them to periodic ‘irritations’” (Ladeur, 1996, p. 21).

Meta-regulation is considered also to enhance companies’ organisational learning about risk identification and mitigation (Parker, 2002). On the regulatory level, impact assessments represent an institutional decision-making procedure. In contrast, on the corporate level, they are perceived as a “technical tool for analysis of the consequences of the planned intervention (policy, plan, program, project), providing information to stakeholders and decision-makers”(IAIA, 2009. p. 1) Like enforced self-regulation, meta-regulation thus represents the first step of the enforcement pyramid of responsive law (Parker, 2002; Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992). Also, the theory of meta-regulation involves the aim to engage civil society in ensuring accountability for self-regulation (Parker, 2002; Gilad, 2010). However, it is often also adopted to counteract the regulators’ resource scarcity (Black, 2006, p. 22). The legitimacy of legally mandated IA that assesses fundamental rights impact can be questioned, where the standard definition is ultimately allocated to a standard setting organization (Fraser & Bello Y Villarino, 2023; Veale & Zuiderveen Borgesius, 2021).

An essential feature of meta-regulation is the establishment of internal controls for risk-management (Gellert, 2020). In a risk-based regulatory approach the regulator adopts flexible standards to “fit the particular risks to which the conduct of that particular firm gives rise.” (Black, 2006, p. 4). This regulatory approach emphasises the explicit selection of key normative values and risks that threaten the firms rather than focusing on enforcing rules homogenously across the regulatory sector (Black & Baldwin, 2010). Mandatory PBIAs may represent regulatory tools within the broader risk-based regulatory strategy (Black, 2005; Black & Baldwin, 20102012; Gellert, 2018; Gonçalves, 2020; Kaminski, 2023); as in the case of FRIA in the context of AI Act. Deep exploration of the topic of quantifiability of risks to rights and engagement with theories of risk (See Roeser et al., 2012a, b), risk management (See Dionne, 2013; Gellert, 2020) or risk-based regulation (Baldwin et al., 2012; Black, 2005, 2010; Rothstein et al. 2006; Black & Baldwin, 2010) is beyond the scope of this article. However, it must be highlighted that IAs may serve a range of risk-based regulatory objectives. First, risk regulation may refer to regulators relying on quantitative methodologies to assess risks. Second, IAs the may represent a tool to the continuous, “internal enterprise risk management” (Kaminski, 2023, p. 1406), which the regulator may seek to nudge (ibid). Third, instruments such as EIA may also seek to enhance the democratic deliberation surrounding the initiative assessed. Finally, IAs may represent means to distribute enforcement resources on the basis of risk quality and severity, as in the case of the GDPR and the AIA (Kaminski, 2023). However Yeung and Bygrave (2022) view the DPIA of the GDPR to be normatively incompatible with quantitative and resource-oriented approaches to risk regulation because “fundamental rights’ jurisprudential structure and philosophical foundations as setting universal moral boundaries.” (Yeung & Bygrave, 2022, p. 146). Instead, FRIA should represent a “risk-based approach”, rather than risk-based regulation. Against this background, risks to fundamental rights should be evaluated against a contextual, qualitative standard: clear violations would entail refraining from the planned activity, whereas actions that could constitute borderline violations should be matched with measures proportional to their severity and probability (Ibid).

Impact assessment processes presuppose that initial plans can be changed in a manner that alleviates the unwanted impacts. In the context of technology, this would mean altering the design of a technical solution, which involves organisational elements as well as hardware and software. Thus, impact assessments represent design-based regulation (Yeung & Dixon-Woods, 2010). The approach recognizes the power of technology in shaping human conduct with an effect stronger than laws (Bygrave, 2022). The design reflects the values at stake (Winner, 1980) and could be deviced to account for, for example, fundamental rights (Hildebrandt, 2015). The regulation may be implemented in a manner where the technical design prevents non-compliance (Lessig, 2006; Yeung, 2008; Yeung & Dixon-Woods, 2010), which could even be automated (Bygrave, 2022). By-design approaches are adopted in the context of privacy (Cavoukian, 2009) data protection law (Arts. 24, 25, 32, 34, 36 GDPR Binns, 2017; Bygrave, 2022) and discussed in the context of cybersecurity (Bygrave, 2022) and algorithmic decision-making and attached to values such as the rule of law (Schartum, 2020) and legal certainty (Pöysti, 2023). Design-based approaches are also a form of “pre-emptive, ex ante facto risk-based” regulation (Bygrave, 2022, p. 152) and a form of meta-regulation, wherein the regulator delegates the responsibility to the designer of the system (Yeung & Bygrave, 2022). However, by-design approaches raise questions about the assessees’ and assessors’ ability to apply complex normative frameworks to their operating context (Yeung & Bygrave, 2022), the possibilities of translating values into technical solutions (Koops & Leenes, 2014; Koulu, 2021; Schartum, 2020) and the long-term legitimacy of hard-coded solutions (Almada, 2023; also Yeung, 2008). In the context of AI, impact assessments may be a tool for the regulation of algorithms but also result in by-design solutions which represent regulation by algorithms (Ulbricht & Yeung, 2021).

Could a regulator, in principle, deploy an algorithmic decision-making system to confirm whether an AI system or its deployment of AI poses an inappropriate level of risks? This would require the system designer to predict the possible inputs from the physical world and about the system in question and find a formalized expression to them as well as the decision-making criteria (Schartum, 2020). Although there is optimism about the potential of automated law in the public sector, it is contingent on identifying narrow enough application contexts and sufficient encoding of procedural safeguards (Pöysti, 2023; Schartum, 2020). First, questions arise about the relevant training data, considering the scarcity of IAs that are made publicly available (See IAIA, 2021) Second, it is questionable whether this is possible and desirable for PBIAs such as FRIA, that covers 50 fundamental rights considering the sociotechnical complexity, scale and range of application contexts of social media platforms, AI systems or surveillance technologies. Third, automation would be unviable for IA models that rely on more inductive and qualitative approaches to identify the relevant values and harms at stake, such as SIA. Finally, it is highly doubtful, whether IA systems could be devised to weight on the relevant values at stake against in the particular case in a nuanced manner, considering the uncertainties involved with the project (IAIA, 2021) and its novelty, which would translate into inputs that are not represented in the training and testing data.

From the perspective of welfare economics, IAs reduce the information asymmetry between the regulator and regulate, where the regulator has mandated access to the IA results. Impact assessment can be adopted as a means to internalise the negative externalities of the assessed activity or project. It may also be deployed to control for externalities associated with the specific use of technology (Art. 29a, AIA, 2024). Several economic arguments may favour the ex-ante internalisation of externalities through the imposition of a mandatory impact assessment and risk mitigation process instead of using ex-post liability rules. The assessee may be able to minimise the externalities at the lowest cost due to the superior position to identify and mitigate them (Calabresi & Melamed, 1972). At the same time, the absence of regulation (Kaminski, 2023) or traditional ex-post liability rules may be insufficient to incentivise internalisation. For example, the impact may be irreversible or manifest over a very long period, potentially concerning only future generations (Ogus, 1994, p. 35). The damage may be so significant or occur on such a vast scale the assessee may also be unable to pay for the damage (Baldwin et al., 2012). The transaction costs administering the ex-post solution may also be too high (Ogus, 1994, p. 38; Baldwin et al., 2012), for example, due to procedural costs of filing class actions (Gunningham et al., 1998a, b). Algorithmic harms may occur on a wide scale (Alvesalo-Kuusi et al., 2022; Art. 34–35 DSA; Art. 3 (44d) AIA, 2024) and be difficult to prove (See Hacker, 2018).

Project-based impact assessments focus on risks that are “generally known or at least knowable” (Pöysti, 2024) and within the control the assessee, who implements the project. In contrast, regulatory impact assessments are an essential tool for risk regulation (Black, 2010; Bounds, 2010) of systemic risks (Wiener, 2010). Similarly to a project-based impact assessment, a regulatory impact assessments represents a future-oriented process of information inquiry. Besides regulating risk, the instrument may serve other goals, such as parliamentary control of rulemaking carried out by the executive branch (Alemanno & Meuwese, 2013), or enhancing the quality of law-making (EC, 2021b). The norms and goals for regulatory impact assessments differ between jurisdictions (Renda, 2006), reflecting their constitutional order. Given the wider range of objectives and norms associated with regulatory impact assessments, their potential status as a distinct, higher-order legal design pattern will not be reviewed in this study.

4 Project-Based Impact Assessment as a Legal Design Pattern

4.1 Name and Design Solution

Following the pattern description by Koulu et al. (2021, p.24), I name the pattern a project-based impact assessment (PBIA), also known as a project-based risk assessment. As described in Sect. 1, this design pattern is present in several fields of law. In addition, the PBIA is adopted as a form of self-regulation and meta-regulation. The PBIA process begins with the assessment phase, where data is collected to predict and review the impact of the project and the measures to contain unwanted impacts, including alternative project designs, are identified. The process results in a report that informs decision-making on the ultimate design (or non-execution) of the project and the relevant risk mitigation measures. In the subsequent implementation stage, complying with the plan is crucial and should be accompanied by monitoring and accountability instruments. Upon the change of circumstances, the PBIA is revised through a new process.

The critical party to the PBIA process is the assessee, who plans and implements the project. In many PBIA models, the assessee also acts as the assessor of impacts (GDPR; DSA; AIA, EP Proposal). However, they may also share this role with the regulator, for example, where the regulator needs to be consulted during the self-assessment process (Art. 36 (1) GDPR) or where the PBIA needs to be approved by the regulator (Art. 9 EIAD; Art. 36 (5) GDPR). A third-party assessor may also carry out the assessment. In addition, other actors, such as representatives of the public, may take at least a partial role of an assessor (See Art. 34 (1) DSA). Involving and consulting those directly impacted by the planned project, their representatives, and other stakeholders is typically prescriptive to the PBIA process (EIAD; Vanclay et al., 2015; Moss et al., 2021). Documentation and transparency of the PBIA process contribute to stakeholder participation and facilitate the subsequent monitoring, accountability and review of the PBIA implementation (see EIAD; Mantelero & Esposito, 2021; Vanclay et al., 2015).

4.2 Description of the Problem and Conflicting Forces at Play

Describing the conflicting forces at play is essential for uncovering the functional purpose of a design pattern (Alexander, 1979, p. 251). PBIA is deployed to remedy the problem of foreseeing unwanted impacts of an activity or a project and mitigating them in advance by redesigning the planned activity. The PBIA process seeks to resolve six interconnected tensions.

The constitutive, normative conflict is between perceived benefits of carrying out the desired activity, for example, building a new power plant or a solution for processing personal data, and its potential harms to the environment, rights of others or other values, which may be immediate or occur in the future. The relevant normative values, as well as the range of potentially conflicting stakeholder interests, vary depending on the nature and context of the planned activity. Some PBIA models determine the values at stake (Art. 34 DSA, Art. 35 GDPR; Art. 29a AIA, 2024; Art. 16, CoE, 2024), whereas others prescribe the process of inductively discovering the relevant values alongside the impacts on the values identified (See Vanclay et al., 2015; Sanfilippo & Frischmann, 2023; Sen, 1993). Furthermore, PBIAs may also couple prescriptive and inductive normative approaches (See Clarke, 2009; Mantelero, 2018; Mantelero & Esposito, 2018; Raab, 2020).

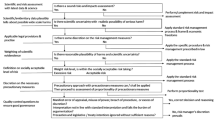

Mandatory PBIA seeks to resolve the regulatory tension between self-regulation and command and control regulation by regulating the assessment process (see Sect. 3). In practice, any of the elements of the PBIA process of Fig. 1 may be determined by law. According to Moss et al. (2021), the accountability of algorithmic IA’s may only result from their legitimisation “through legislation or within a set of norms that are officially recognised and publicly valued. Without a source of legitimacy, IAs may fail to provide a forum with the power to impute responsibility to actors.” Due to its shortcomings in technology regulation, such as issues with accountability (Baldwin et al., 2012), self-regulation is hypothesised to represent a potential AntiPattern, a design that consistently fails to solve the problem it is meant to address. (See Koulu et al., 2021, p. 25.) However, self-regulation may be better than nothing. Where companies are inherently motivated and committed to voluntary corporate responsibility (Parker, 2002), voluntary PBIA processes in corporate due diligence may ensure a higher level of human rights protection than enjoyed by citizens in the given country (see Kemp & Vanclay, 2013). PBIA’s may also be products of co-regulation (Raab, 2020), wherein the regulator determines the outline of the PBIA, and the companies, communities of practice or standard setting organizations define the detailed rules for carrying out the process. This regulatory solution is adopted in the context of AI Act, where the compliance standard for the impact assessment-like provisions of Art. 9, Art. 10 and Art. 54d are to be specified by standard setting organizations or codes of conduct (Art. 40; Art. 52).

Also, an overly detailed, legally mandated PBIA process may fail due to its misfit with the “institutional logics of the private sector” (Selbst, 2021, p. 117; see also Teubner, 1985, p. 311). PBIAs, both as a report and as a process, seek to structurally couple distinct, autopoietic social subsystems (see Luhmann, 2013), wherein the process produces irritations between the relevant subsystems (see Ladeur, 1996). Possible subsystems include the legal system, the economic system, the technical system, and the social systems of stakeholders impacted by the project. These may be, for example, the civil society or systems which are autopoietic but not social, such as the ecologic system. For example, the guidelines for social impact assessment advise accounting for distinct cosmological systems of indigenous communities impacted by a project (Vanclay et al., 2015). Furthermore, the professional community refining the PBIA process and conditions (see Lawrence, 2013) may represent another subsystem.

Actors involved in the PBIA process, especially the assessor, are under pressure to understand, combine and communicate inputs from different domains to uncover and predict impacts and monitor the compliance process (See Kemp & Vanclay, 2013). The presence of distinct social subsystems translates to epistemic tensions. The tensions are exacerbated when the PBIA process and report are not transparent. The assessors may have a limited cognitive capacity to understand the assessees’ and impacted stakeholders’ operating context (See Moss, 2021). Carrying out PBIA is also subject to temporal-epistemic tension: the limitations of predicting future causal relations. The project has not yet materialised. Therefore, the decisions on whether to execute it involve uncertainty and are at the mercy of what is foreseeable ex-ante. Assessors’ capabilities to foresee risks are generally limited by their own ignorance (Hoffmann-Riem & Wynne, 2002).

Economic forces qualify the resources consumed as well as the transaction costs and externalities at play. The use of more resources to carry out the PBIA can overcome, to an extent, some of its epistemic shortcomings. However, the PBIA process must also overcome the temporal-economic tension. Since PBIA is carried ex-ante, it may delay the execution of the planned activity. The delay may originate not only from scoping the impacts but also from implementing the changes aimed at mitigating the unwanted effects. In the worst case, the assessee may be precluded from carrying out the planned activity, not because of its inherent risks but due to excessive assessment costs and time. In such an event, the assessee and the society are precluded from the benefits of the planned activity. Prohibitive assessment costs may also prevent smaller actors, such as SMEs, from initiating their projects, which, depending on the values at stake, may be undesirable. Finally, it must be noted that the obligation to carry out a PBIA may bind not only companies but also public actors (Art. 34–35 GDPR; Art 29a AI Act, 2024, Art. 16, CoE, 2024). Nevertheless, public actors may experience similar frustrations concerning compliance as companies (Wernick et al., 2023).

The project-based impact assessment must address the normative-economic conflict. As discussed in Sect. 3, PBIAs are often employed to internalise and minimise externalities ex-ante in contexts where the implications of the project may be so complex, widespread or irreparable to address with ex-post measures. Wherein the PBIA is not regulated or executed thoroughly, the management of negative externalities either fails or remains dependent on adopting complementary liability rules or other legal design patterns (See Braithwaite, 1982; Gunningham et al., 1998a). This way, normative-economic conflict interconnects with the regulatory tension underlying PBIAs.

The prescription of a PBIA process determines the normative values at stake and provides a benchmark for the adequate scope, cost and duration of the inquiry into externalities caused by the activity. The legal obligation and instructions to carry out the PBIA process reduce the shortcomings associated with self-regulation (See Parker, 2002). Executing a PBIA codifies the process of inquiry on the impacts, determination of unwanted effects and decision-making based on the inquiry. Moss suggests that the concept of an impact functions as a boundary object (Moss et al., 2021; Star & Griesemer, 1989) between different systems and epistemic communities during the assessment process. The concept of a risk is likely to serve a similar function (See Luusua & Ylipulli, 2020). In addition, the well-documented PBIA report in itself functions as a boundary object during the implementation phase. Ideally, a PBIA legitimises the inquiry into the project’s impact despite its epistemic limitations. A PBIA also allows for accommodating conflicting interests and mitigating unwanted effects in advance while potentially limiting the ex-post civil liability (See Lopez, 2019) and accountability of the executor of the assessed activity concerning unforeseen impacts. The process and its product may thus be used to demonstrate due diligence (See Sect. 1). While not every PBIA process may be executed perfectly, recurring assessments enhance the regulator’s learning on the regulated domain (Selbst, 2021) as well as refine the skills of the assessor community (Lawrence, 2013). The temporal-epistemic tensions are overcome by determining the conditions under which the PBIA process should be reiterated.

4.3 Context and Conditions for the Patterns’ Applicability

A project-based impact assessment presupposes the existence of a planned activity which is not yet materialised. For example, the GDPR requires data protection impact assessment to be carried out “prior to the processing” (Art. 35 (1) GDPR), and the AI Act proposal “Prior to deploying a high-risk AI system “ (Art. 29 A(1) AI Act, 2024). The activity in question must be of a type which has serious externalities, the costs of which are usually not internalised by the executor of the activity and which are ineffective to govern through ex-post measures (see Sect. 3). For example, under the DSA, the risk assessment process concerns very large platforms and must begin on the date their compliance obligations begin (Art. 34 DSA). At the same time, the presence of the constitutive normative conflict suggests that the planned activity holds value, which, when appropriately designed, could be welfare-enhancing. Consequently, the activity in question is not prima facie banned or subject to a moratorium (see Art. 16 (4) CoE, (2024); Art. 5 AIA, 2024) on the grounds of the precautionary principle (see Pöysti, 2023).

A project-based impact assessment also assumes that the assessee is in the best position to identify the relevant impacts and assess and mitigate them. Otherwise, the regulator may have chosen to regulate projects of this kind through specific ex-ante criteria (EIAD). The assessee must have control over the start and implementation of the said activity. The raison d’ être for the criterion is the possibility to refrain from the activity where adverse effects are perceived insurmountable or to revise the plan in a manner that prevents or mitigates the unwanted effects. Hence, as a legal design pattern, PBIAs are closely coupled with by-design approaches, wherein technology or activity is deliberately designed, ex ante (Bygrave, 2022) to respect specific values, such as data protection principles (See Sect. 3). In fact, the controller’s obligations under Art. 25 GDPR represent a tacit legal design pattern of a PBIA under the guise of the legally mandated by-design approaches.

Where the assessment concerns an ongoing, hard-to-control phenomenon, such as a natural event, emerging technologies or markets, or multiple ongoing activities by several assessees, we are observing a distinct, higher-order legal design pattern of regulatory impact assessments. It includes instruments such as technology impact assessments and strategic and cumulative impact assessments. The same applies to impact assessment for activities that yield intangible results with indirect material effects, such as rules, regulations and policies, typically referred to as legislative or strategic environmental impact assessments (See Sect. 1 and 3). In some cases, it may difficult to designate boundaries for technologies and their impact (Raab, 2020), as in the case of online platforms (Art. 35 DSA) or assemblages of surveillant technologies (See Haggerty & Ericson, 2017). Where the IA in question is aimed to inform the assessee’s decision-making on the design of the assessed constellation of technology, I deem it to still represent the legal design pattern of PBIA.

On a program or policy level, conducting a risk or impact assessment is an explicit precondition for assessing the relevance of applying the precautionary principle (EC, 2000; Pöysti, 2023). Where the risks of the assessed subject, such as emerging technology application, are unknown or scientifically unverifiable, the legislator relies on the on the legal design pattern of precautionary approach. Where a PBIA is legally mandated, the legislator has often evaluated the activity in question not to trigger the exercise of a precautionary principle, presupposing its risks and impacts being foreseeable or “generally known or at least knowable” (Pöysti, 2023). However, a PBIA may result in a more context-specific, second-order exercise of the precautionary principle, where the risks identified exceed what is permitted, and they cannot be mitigated (Art. 29 a (2) AIA, EP). The distinction between IAs and the precautionary principle can also be drawn from Hans Jonas’ ethics. Humans are vested with responsibility for the impact that technology confers on future generations. This responsibility is active and proportional to the scale and power of technology and contains an obligation to “to refrain from acting when we realize the future harms resulting from actions and modify our actions when we are uncertain as to the harmful long-term consequences” (Morris, p. 188). IAs are means to exercising the duty of care of future generations. However, where we cannot foresee the the future impacts of technology, we should presume “the prophecy of doom” and refrain from action (Morris, 2013, p. 188), i.e. exercise the principle of precaution (Pöysti, 2024),

Whereas the procedural rules on collecting, accepting and interpreting evidence in court procedures aim to reconstruct an event that occurred in the past (See Diver, 2024), PBIA processes sketch out a future yet to come. Because PBIAs aim at future-proofing, they represent a pattern distinct from auditing, or so-called ex-post impact assessments (Raji et al., 2020), where the already materialised activity is evaluated against a range of normative parameters. However, audits can also represent a means to monitor or enforce measures assigned to the audited entity following the earlier IA. For example, the DSA requires very large platforms to carry out both IA’s and audits.

Moss et al. underscored the necessity of the assessors being independent both from those designing or deploying the system and the forum allocating the responsibility (2021). Such a qualification is more closely associated with the auditing process but represents only one of the sub-patterns for PBIA. The DSA adopted a design mix where a very large platform produces the IA but where a third party audits compliance. Both the GDPR and AIA proposals rely on self-assessments by data controllers or AI deployers. The competent authority is notified of the IA and, under certain conditions, is more closely involved in the IA process. This regulatory approach is consistent with Selbst’s observation of IA execution being dependent on access to the knowledge of those developing the technology (2021).

5 The Tensions within the Pattern Language of Impact Assessments

5.1 The Internal Pattern Language of Project-Based Impact Assessments

In the previous sections, I outlined the design solution put forward by a PBIA, the relevant tensions it seeks to balance and its relationship with other legal design patterns in the context where it is adopted. In this section, I outline the pattern language internal to PBIAs and explain the role of each sub-pattern in balancing the tensions associated with impact assessments. These sub-patterns are illustrated in Fig. 1. As a process, impact assessment is divided into assessment (1–5, 10) and implementation phase (6–10). The two phases constitute the archetypal, prescriptive pattern language of an impact assessment:

-

1.

screening for the need to carry out our assessment

-

1.1.

A potential decision not to carry out the assessment

-

1.1.

-

2.

defining the scope of the project and the assessment process

-

3.

a data collection process to identify, predict and evaluate

-

3.1.

the impact of a planned but not yet executed project concerning specific normative values or risk categories

-

3.2.

actions and designs that remove or mitigate the unwanted impact, including alternative project designs

-

3.1.

-

4.

a written report documenting the process 3.

-

5.

the use of the inquiry 3–4 to inform decision-making on the execution of the project

-

5.1.

A potential decision not to execute the project

-

5.1.

-

6.

the subsequent process of implementing the project according to 3–5

-

7.

monitoring that the project is executed based on 3–5

-

8.

the establishment of accountability instruments against failing to follow the impact assessment process correctly or implementing the project according to 3–5.

-

9.

a review of whether commencing a new impact assessment is necessary

-

10.

The entire process and the report are subject to transparency requirements

Besides determining the rules for a PBIA, the regulator may be more actively involved in any of the steps between 1–10. A third party assessor may take the main responsibility for carrying out the steps 1–10. Stakeholder involvement may take place at multiple stages of the IA process.

5.2 Screening

The impact assessment process begins with an awareness of the potential need to carry it out. This phase is referred to as screening (Vanclay et al., 2015) or a “catalysing event” (Moss et al., 2021, p. 15). Most impact assessment processes are initiated by the assessee, which places pressure on their awareness of the normative values and compliance frameworks relevant to their project. The impact assessment process may be part of a broader palette of compliance obligations triggered by one condition, such as qualifying as a very large platform under the DSA (recs 77–79, Art. 33 (6) DSA) or as a deployer of a high-risk AI system (Art. 29a AIA, 2024). Environmental impact assessment and data protection impact assessment are triggered by plans to engage in activities that the legislator perceived to involve higher risks (Arts. 3–4 EIAD; Art. 35 (1) and (3) GDPR). However, the trigger point may be more vague and epistemically and systemically more challenging. For example, GDPR requires the controller to comply with the data protection by design principle and be aware of the possible impacts of processing on the rights and freedoms of natural persons (Art 25 GDPR; See Bygrave, 2022; Yeung & Bygrave, 2022).

5.3 Scoping

In the second stage of the impact assessment, it is necessary to identify the scope of the project, the relevant context in the light of the values at stake as well as the assessment process, including the resources it requires (Vanclay et al., 2015, Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2020, See also Mantelero, 2022). Scoping ensures that PBIA is proportionate (Jha-Thakur et al., 2022) and thus balances normative, economic and temporal forces at play. At this stage, the assessor is also advised to identify the PIA-relevant issues and risks with the” potential to be of concern” (Vanclay et al., 2015, p. 8). Stakeholders to be consulted may be preliminarily identified during this phase (Mantelero, 2022; Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2020). This stage carries more weight in PBIAs, where the impacts are determined more inductively, as in the case of connection with environmental and social impact assessments or capabilities-based approaches to assess the technology impacts (Sanfilippo & Frischmann, 2023; Sen, 1993). In contrast, the DPIA is more explicit about the scope of risk assessment and values at stake. Nevertheless, engagement in scoping is a meaningful stage of any PBIA process, even when not explicitly mentioned by law or in the PBIA guidance.

5.4 Data Collection

The data collection phase aims at collecting empirical evidence on future events (See Diver, 2024). The method and process of data collection facilitate the structural coupling and overcoming of epistemic boundaries between the legal, business, technical and stakeholder communities. The data collection methods are often instrument-specific and subject to refinement in the assessor communities. In some PBIA models, data collection also aims to identify the baseline level against which the impacts are assessed (See Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2020). The data collection procedure links the different social systems relevant to the PBIA process.

For this reason, the involvement with the impacted persons and communities is a recurring prescription for a PBIA process (EIAD; Vanclay et al., 2015; Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2020; Raab, 2020; Moss et al., 2021; Brussels Privacy Hub, 2023; Stahl et al., 2023). The scope and depth of the public stakeholder consultation in the IA process is perceived essential for its effectiveness and legitimacy (Moss et al., 2021; Götzmann, 2019). Nevertheless, both the facilitation of stakeholder consultation and taking part are subject to transaction costs (see Esteves et al., 2012) and may conflict with the economic interest of the assessee (Kaminski & Malgieri, 2020). Furthermore, the impact assessment process may be rendered ineffective due to the non-transparency of the assessed organisation and technology to the third-party assessor (Raji et al., 2020).

The acts and proposals under review introduce different degrees of public consultation to the IA. The controller shall seek views of data subjects or their representatives without prejudice to commercial or public interests or security of operation (Art 35 (9) GDPR). Under the DSA, very large platforms “should, where appropriate,” engage in broad stakeholder consultation (rec. 90). The Draft Framework Convention for AI obliges to consider “where appropriate the perspectives of stakeholders in particular persons whose rights are impacted” (CoE, 2024 Art. 16 (c)). However, the commitment to stakeholder consultation was weakened during the negotiations for AIA (Art. 29a, EP, 2023 vs. Art. 29a, 2024) and the Framework Convention for AI (Art 29, CoE, 2023a, b vs. Art. 16 (c), CoE, 2024). Against the recommendations of the academic community (Brussels Privacy Hub, 2023), the currently the AIA act mentions IA-adjacent stakeholder consultation only in the recitals (recs. 42a, 58g, 2024) albeit stakeholder representatives are part of other governance instruments under the Act.

5.5 Assessment, Redesign and Risk Mitigation

The impact assessment can be defined as the “process of identifying future consequences of a current or proposed action. The ‘impact’ is the difference between what would happen with the action and what would happen without it” (IAIA, 2009). In the assessment phase, the project’s impacts are evaluated based on various parameters, such as likelihood and severity (Mantelero, 2022). The identified impacts are typically prioritised for the purposes of identifying measures to mitigate them (Vanclay et al., 2015). Remendability of a risk may be one of the prioritising factors (Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2020). Some PBIA models also require the consideration of indirect impacts (EIAD, Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2020).

As discussed in Sects. 1 and 3–4, PBIAs may involve both the assessments of risks and impacts, and the language of mandatory PBIAs may refer to both. How is data being assessed, what is being assessed (risk or impact) and the threshold of identifying an unacceptable level of risk or impact varies greatly between diverse PBIAs (See Moss, 2021). Furthermore, number of risk and impact assessment methods may be accepted or developed under the rubric of a specific PBIA (See ISO/IEC, 2019; Stahl et al., 2023; Wairimu et al., 2024; Iwaya, 2024). Generally, PBIAs that seek to measure risks to rights would presuppose a more qualitative assessment method, which should be informed by the interpretations by the relevant regulatory authorities and case-law (Yeung & Bygrave, 2022).

Where an unacceptable level of impact or risk is identified, an impact assessment process should be coupled with a review of designs that remove the unwanted effects (See Art. 9 (4)(2)) or solutions that mitigate them (See Art. 9 (4)(b) AIA, Art. 52d (2) 2024). Where necessary, and reasonably feasible, alternative designs for the project should be considered. These actions are essential to the PBIA process on the basis of rationales for by-design regulation, welfare economics (See Sect. 3) and the active duties of care toward future generations (See Sect. 4). However, as in the case of stakeholder consultations, the mandatory PBIAs do not always include this requirement. Some do not even feature an obligation to consider the measures to mitigate the identified harms—the FRIA of the AI Act obliges the AI deployers to identify measures to be taken if the risks materialize (Art. 29a (f), 2024; cf. Art. 29a (h), EP, 2023). Obviously, the deployers have limited means to influence the design of the AI system, in comparison to their producers, who are obliged to remove or mitigate the risks they have identified (Art. 9 (2) AIA, 2024). However, considering that deployers may have considerable influence over the context where the system is deployed, the wording undermines the effect of the FRIA.

Among the sub-patterns that impact the assessment process, the assessment and review of alternative designs are most decisive for resolving the tensions associated with the legal design pattern. The accuracy of the assessment is subject to epistemic-temporal and economic constraints. Limiting the risk assessment to foreseeable risks or impacts strikes a balance between the epistemic-temporal tensions and normative values determining what qualifies as risk or impact. Prioritising the risks to be mitigated balances the normative, regulatory, and economic tensions. The identification of mitigation measures and alternatives demands cross-systemic interaction.

5.6 Report and Decision-Making

Compiling a report on the data collection and impact assessment process, as well as the relevant mitigation measures and alternative designs, is an essential way to fuse knowledge from the domains relevant to the impact assessment process. The report provides the blueprint for technical implementation while enabling monitoring and enforcing compliance. The goal is to use the document to inform the decision-making process on the project. In environmental impact assessment, where the regulator approves the project based on the impact assessment, the decision-making stage is clear-cut. In the earlier draft for FRIA of the AIA, an obligation to abandon the project where risk mitigation measures could not be identified (Art. 29a (2), implied to the decision-making stage.