Abstract

Rawls famously argues that the parties in the original position would agree upon the two principles of justice. Among other things, these principles guarantee equal political liberty—that is, democracy—as a requirement of justice. We argue on the contrary that the parties have reason to reject this requirement. As we show, by Rawls’ own lights, the parties would be greatly concerned to mitigate existential risk. But it is doubtful whether democracy always minimizes such risk. Indeed, no one currently knows which political systems would. Consequently, the parties—and we ourselves—have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice in favor of political experimentalism, a general approach to political justice which rules in at least some non-democratic political systems which might minimize existential risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nowhere in his substantial body of work does Rawls address existential risk. In fact, scarcely anything has been written on existential risk in the vast secondary literature on Rawls’ theory of justice. This silence is unfortunate. It is hard to deny that the parties in the original position would be greatly concerned to mitigate existential risk, which threatens the lives and fundamental interests of both present and future generations. The parties must agree upon principles of justice which they would want all previous generations to have followed (Rawls, 2001: 160). Presumably, no generation would want previous generations to have followed principles of justice which, by failing to mitigate (or even exacerbating) existential risk, threatened its very existence. But then one of the parties’ greatest concerns would be to agree upon principles of justice which did not hinder our capacity to mitigate existential risk.

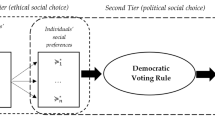

What do principles of justice have to do with existential risk? Rawls famously argues that the parties in the original position would agree upon the two principles of justice, which guarantee citizens “the same indefeasible claim to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic liberties” (ibid.: 42). This scheme includes equal political liberty, which grants citizens an equal right to vote (“one person, one vote”), equal access to public office, and the like (Rawls, 1999: 196, 203). But as we shall contend, it is doubtful whether political systems which grant citizens equal political liberty—that is, democracies—always minimize existential risk.Footnote 1 And no one (including the parties) currently knows which system or systems would. So the parties have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice in favor of what we shall call political experimentalism: not a specific political system but rather a general approach to political justice which permits experimentation with at least some non-democratic systems to determine which best promote our various political ends—including existential risk mitigation.

We begin in Section 2 with a quick overview of existential risk. We then discuss a substantial body of work which shows that democratic decision-making is compromised by three pathologies—voter ignorance, voter irrationality, and democratic short-termism—which hinder democracy’s capacity to deal with complex problems like existential risk. We close with a brief outline of political experimentalism.

In Section 3, we interpret the deliberations of the parties in the original position in light of the general facts adduced in Section 2 about existential risk and democracy’s pathologies. The parties “know whatever general facts affect the choice of the principles of justice” (Rawls, 1999: 119). Hence, they know that it is doubtful whether democracy always minimizes existential risk. Consequently, they have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice in favor of experimentalism.

Sections 4 and 5 address various objections to our argument. In Section 4, we address several possible objections to our interpretation of Rawls’ theory, showing that the general facts we discuss in Section 2 do in fact give the parties reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice. In Section 5, we address two separate objections to our claim that it is doubtful whether democracy always minimizes existential risk: the objection from epistemic democracy and the objection from democratic reform. We conclude in Section 6 with a short discussion of some of our argument’s broader implications.

There are two caveats before we proceed. First, we do not claim to know which political system or systems would in fact minimize cumulative existential risk (or, for that matter, any individual existential risk). Indeed, we do not even claim to know definitively that democracy itself would not do so. We claim only that it is doubtful whether it always would.Footnote 2 This claim, we hold, itself gives the parties some reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice. It does not, however—our second caveat—necessarily give them all-things-considered reason to reject that requirement. It is beyond the scope of this paper to evaluate all the considerations—in particular, considerations of self-respect—which Rawls and others have proposed in favor of the requirement of democracy.Footnote 3 And of course, existential risk mitigation is itself only one of the many political ends which the parties must take into account in their deliberations. Thus, we argue here only that considerations of existential risk give the parties significant (but not necessarily all-things-considered) reason to reject the requirement of democracy.

2 Existential risk, the pathologies of democracy, and political experimentalism

2.1 Existential risk

What is existential risk? Toby Ord defines existential risks—or x-risks—as risks of existential catastrophes which would destroy humanity’s long-term potential (Ord, 2020: 6).Footnote 4 In the spirit both of this definition and of Rawls’ theory of justice, we define existential risks as risks of existential catastrophes which would permanently destroy humanity’s ability to develop and exercise our two moral powers: our capacity for a sense of justice and our capacity for a conception of the good.Footnote 5

Paradigmatic examples of possible existential catastrophes include natural extinction events such as asteroid impacts, naturally occurring pandemics, supervolcanic eruptions, and stellar explosions; anthropogenic extinction events such as nuclear holocausts and engineered pandemics; and extinction events arising from both natural and anthropogenic factors such as tail risks of runaway greenhouse effects.Footnote 6 All these catastrophes would eliminate our species and (a fortiori) destroy our ability to develop our moral powers. But existential catastrophes need not involve extinction. On our account (like Ord’s), the emergence of a dystopic system of universal human oppression from which we could never recover would also constitute an existential catastrophe, even if it did not literally wipe us out (Ord, 2020: 145–155).Footnote 7

Naturally, we are and should be interested in mitigating risks of all sorts. But x-risks are especially grave. While humanity could potentially recover from a non-existential catastrophe, a true existential catastrophe precludes any possibility of recovery. Hence, x-risk mitigation is a wholly proactive endeavor.

In assessing different political systems’ capacities to mitigate x-risk, we should bear in mind three features of most x-risks:

-

Long timescales: Many existential catastrophes are unlikely to occur for many thousands—or even millions—of years. For example, an asteroid impact may not threaten humanity with extinction for several million years, because there is an inverse relation between asteroid size and frequency of impact (with more dangerous impacts occurring much less frequently).

-

Low probabilities: Relatedly, most—though not all—existential catastrophes are individually unlikely. For instance, the probability of an existentially catastrophic stellar explosion within the next century is only 1 in 1,000,000,000 (Ord, 2020: 167).

-

Complexity: Many x-risks cannot be adequately understood without a firm grasp of several complex technical subjects. For example, the risk of value-misaligned artificial intelligence cannot be adequately understood—let alone minimized—without a good grasp of computer science, decision theory, and other cognitively demanding fields of study.

In short, most x-risks (though not necessarily all) involve far-off, low-probability, and complex events. Consequently, it is easy to underestimate the threat they pose to humanity. But x-risk is no minor concern. Although the individual probability within the next century of any one existential catastrophe may be quite low, the cumulative probability of all such catastrophes—the total x-risk—may be worryingly and surprisingly high. (Ord (ibid.) estimates it to be roughly 1 in 6.) X-risk is therefore both especially important and especially hard to mitigate.

Unfortunately, we cannot directly study which political systems minimize any given individual x-risk. For obvious reasons, it is impossible to wait until after an existential catastrophe has occurred to learn from experience which political systems dealt with it best. Thus, in assessing different systems’ relative x-risk-mitigating capacities, the best we can do is to study the extent to which a given system promotes informed, rational, and long-term decision-making in general. Plausibly, systems which do not effectively promote such decision-making are ill-suited to deal with problems like x-risk. Of course, such an indirect method can hardly be definitive—one reason we do not claim to know which systems would minimize cumulative x-risk. But it can still be quite fruitful.

2.2 Three pathologies of democracy

Is democracy always best suited to deal with problems like x-risk involving far-off, low-probability, or complex events? We doubt so, because democratic decision-making is compromised by at least three pathologies: voter ignorance, voter irrationality, and democratic short-termism.Footnote 8

First, democratic decision-making is compromised by voter ignorance. Since becoming politically well-informed is highly costly and only minimally beneficial to individual voters, most democratic voters are rationally ignorant (Downs, 1957: 207–219). Decades of research confirm that typical voters are ignorant of even basic facts about the structure and function of political institutions, the identity and platforms of political candidates, and much more.Footnote 9 Unsurprisingly, most voters are also ignorant of important social-scientific subjects relevant to democratic politics—not to mention the many other complex subjects relevant to x-risk mitigation.

Voters’ widespread ignorance has two mutually reinforcing consequences. On the one hand, ignorant voters often support candidates endorsing harmful policies. On the other hand, both prospective and current legislators are incentivized to respond to ignorant voters’ preferences.Footnote 10 The joint effect of these two consequences is the frequent implementation of laws and policies which go against citizens’ interests—including their interest in x-risk mitigation. A salient recent example is contemporary democracies’ ineffective response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Winsberg et al., 2020). If COVID-19 had been much deadlier, the ensuing pandemic could have become a genuine existential catastrophe for which most democracies—and most extant non-democracies—would have been terribly underprepared.

Second, and similarly, democratic decision-making is compromised by voter irrationality. Just as becoming politically well-informed is highly costly and only minimally beneficial to individual voters, so too is conforming to normal standards of epistemic rationality in political belief formation. In fact, in many partisan environments, epistemic rationality can even be penalized. Within some ingroups, for instance, rationally moderating one’s beliefs may result in ostracization and other social costs. Hence, most democratic voters behave in paradigmatically epistemically irrational ways in the political domain. Indeed, most voters are rationally irrational: (practically) rational in their (epistemic) irrationality (Caplan, 2007). Naturally, rationally irrational voters incentivized to form irrational political beliefs are not especially well suited to deal with political problems of any kind. X-risk is no exception.

Third, and maybe most importantly, democratic decision-making is compromised by short-termism. A large body of work in political science suggests that democracies focus unduly on short-term problems at the expense of long-term ones.Footnote 11 Of course, short-termism is not a problem for democracies alone. Some determinants of short-termism are general and pose a challenge for all political systems. For example, many cognitive biases can lead us to neglect long-term issues. In conditions of informational uncertainty about the future, we often discount the value of actions with long-term benefits relative to actions with more certain short-term benefits (Frederick et al., 2002). In addition, we are often more responsive to salient and visible risks than to risks apparent only from abstract reflection or extrapolation from data (Weber, 2006).Footnote 12 But salient, visible, and short-term risks are not necessarily the most threatening ones, and in any case, most x-risks are neither salient, visible, nor short-term. Consequently, most members of any political system can be expected to neglect long-term problems like x-risk, because psychological determinants of short-termism predispose them to biased short-term thinking.

More striking than psychological determinants of short-termism, however, are the institutional determinants of short-termism specifically in democracies (John & MacAskill, 2021: 49–50). These determinants prevent the formation and implementation of long-term policy, undercut political actors’ motivation to mitigate long-term risk, and hinder our capacity to gather information about such risks and reason appropriately about them. If democratic institutions themselves further incentivize us to neglect the long term, then democracy will arguably mitigate x-risk less effectively than other (more long-termist) political systems.

Foremost among institutional determinants of short-termism in democracies are electoral incentives. Because politicians want to be (re-)elected, they tend to prioritize policies which offer constituents visible short-term benefits, since they can benefit politically from implementing such policies while imposing their costs on later generations who cannot sanction them for doing so (Nordhaus, 1975). But electoral incentives are far from the only institutional determinants of short-termism in democracies. Politicians also have financial incentives to be short-termist, because they are often economically dependent on organizations which want them to focus on the short term (Caney, 2016: 143). These and other institutional determinants strongly incentivize democratic political actors to neglect long-term problems—including x-risk.

If democracy is pathologized by voter ignorance, voter irrationality, and short-termism, then we should expect few (if any) democracies to prioritize the goal of effective x-risk mitigation. Even if some do, we should expect the complexity of that task to keep most voters from forming the appropriate policy preferences. Ultimately, most voters do not look very far ahead (or behind) at the ballot box (Achen & Bartels, 2016: 90–115). We can hardly expect them to worry about stellar explosions a million years hence—let alone the next pandemic, which could come at any time.Footnote 13

At this point, it might be objected that democracy may still be less pathologized overall than other political systems, since contemporary democracies arguably outperform contemporary non-democracies. For reasons which we discuss further in Section 5.1, we doubt whether contemporary democracies’ superior performance to contemporary non-democracies is best explained by their democratic institutions themselves. But even if it is, the possibility still remains that some (non-extant) non-democratic systems would perform even better. Since we cannot discount this possibility, and since democracy exhibits unique pathologies of its own, we doubt whether democracy is best suited to deal with problems like x-risk.

2.3 Political experimentalism

To be sure, the fact that democracy is pathologized by voter ignorance, voter irrationality, and short-termism does not logically entail the suboptimality of democratic x-risk mitigation. Without truly exhaustive comparative institutional analysis, no one can definitively show that a political system does or does not mitigate cumulative x-risk optimally. Indeed, we ourselves do not claim to know that democratic x-risk mitigation is suboptimal. Nevertheless, as we argue further in Section 2, democracy’s pathologies seem to give the parties in the original position at least some reason to doubt its x-risk-mitigating capacities and to consider a more experimentalist approach to political justice. Why this is so is perhaps best illustrated with an analogy.

Suppose that Forrest is interested in betting on some upcoming horse races of different distances and kinds: ten-furlong races, harness races, and so forth. Unfortunately, since the books are closing in just a few minutes, Forrest does not have time to research and observe the entire field before placing his bets. As he is deliberating on what to do, he sees a palomino colt gingerly hobble by with three of its legs in casts.

Forrest has only limited and general information about which horses to bet on. Some of that information suggests that no one horse will necessarily be favored to win all the races. (Among other things, different breeds of horses are best suited to different kinds of races.) Accordingly, Forrest has at least some reason to doubt whether any one horse will win all the races—especially the palomino colt, because of its visible injuries. Certainly it is possible that the rest of the field is in even worse physical condition than the colt. Nonetheless, unless Forrest has some particular reason to believe that all the other horses are that systematically injury-prone, he has reason to doubt whether the palomino colt is favored to win all—or indeed any—of the races.

Just as Forrest cannot research and observe the entire field of horses, so too the parties in the original position cannot directly research and observe the entire (innumerable) field of possible political systems. Like Forrest, the parties have only limited information about which political systems to “bet” on—and some of their information suggests that no one system will always minimize x-risk. Social scientists have long held that the laws and political institutions best suited to promote a society’s ends vary with its “climate, geological features, economic characteristics, religion, customs, etc.” (Klosko, 1994).Footnote 14 Accordingly, the parties have at least some reason to doubt whether any one political system always minimizes x-risk—including democracy itself, because of its documented pathologies. Certainly, it is possible that all other systems would mitigate x-risk even worse (or no better). Nonetheless, unless the parties have some particular reason to believe that all other possible systems are that systematically pathologized, they have reason to doubt whether democracy always—or indeed ever—minimizes x-risk.

If not democracy, then which political system does minimize x-risk? As should now be apparent, we doubt whether any one system would always minimize every individual x-risk. Furthermore, even if one alone would, we suspect that the only way to identify it would be to experiment with different systems and compare their capacities to deal with complex, long-term problems like x-risk. Consequently, we claim that the parties have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice in favor of political experimentalism.

Political experimentalism is a general approach to political justice which permits experimentation with a range of different political systems rather than ruling out all possible non-democratic systems in advance. Thus far, human societies have implemented only a small fraction of all possible political systems. Plausibly, the only definitive way to determine the relative advantages (and disadvantages) of systems which we have not yet implemented is to experiment with at least some of them. Consequently, experimentalism permits (or even encourages) experimentation with different political systems to determine which ones are best suited to promote our political ends under different circumstances.

It is beyond the scope of this paper—and, for that matter, the scope of a Rawlsian theory of justice—to offer a comprehensive and systematic account of political experimentalism.Footnote 15 Such an account would address the deontic status of political experimentation (whether it should be required or merely permitted), the appropriate scope of experimentation (how incrementally to experiment, at which tiers of government to experiment, and so on), the appropriate success criteria for political experiments (including time frames within which to evaluate them), the possible advantages of similar experiments conducted by private actors and organizations, and more.Footnote 16 Our purpose here is to show merely the following: Experimentation with some non-democratic political systems—in particular, experimentation with some liberal but non-democratic political systems—may well be permissible on Rawls’ own account of justice. In other words, the parties in the original position have significant (if not necessarily all-things-considered) reason to reject equal political liberty as a requirement of justice, thereby ruling in as possibly just not only democracy itself but also any non-democratic political system which satisfies all the requirements of the two principles of justice besides equal political liberty.Footnote 17

The problem of x-risk clearly illustrates some of the advantages of an experimentalist political approach—not only for the parties themselves but also (more generally) for all of us. Because we cannot determine a priori which political systems minimize cumulative x-risk, and because we have reason to doubt whether democracy always does, we have at least some reason to rule in at least some non-democratic systems as possibly just. Doing so would allow different societies to determine through experimentation which political systems deal best under their respective circumstances with various x-risks and other serious problems.

Naturally, until we have experimented more widely with different political systems, we can only speculate as to their relative capacities to deal with problems like x-risk. Nonetheless, it is surely possible that some non-democratic systems would in fact mitigate cumulative x-risk better than democracy, either by incentivizing a greater focus on the long term or by reducing the harm of voter ignorance and irrationality (or both). Perhaps epistocratic systems would mitigate x-risk better than democracy under some circumstances by reducing the political influence of ignorant and irrational voters, or by changing political selection mechanisms to promote the selection of more informed or more rational political leaders (or both).Footnote 18 Under other circumstances, lottocratic systems might excel by removing harmful short-termist electoral incentives (Guerrero, 2014). Or it may be that a hybrid political system combining different forms of government would minimize x-risk or that some new and hitherto unconceived system would fare best.Footnote 19 Again, we do not claim to know which political systems would minimize cumulative x-risk. (And it is possible that different political systems would minimize different x-risks under different circumstances—a possibility which seems to count in favor of more experimentation.)Footnote 20 We claim only that it is doubtful, in view of the available evidence, whether democracy itself always does so.

3 Existential risk and Rawls’ theory of justice

The parties in the original position know the general facts about x-risk. They know, for example, that a nuclear holocaust could possibly destroy humanity. They also know the general facts about democracy’s pathologies, just as (and because) they know the general facts about political affairs and human psychology (Rawls, 1999: 119). Additionally, they know that some non-democratic political systems are possibly less pathologized than democracy. The veil of ignorance does not hide any of this information from them: “There are no limitations on general information” which is “well established and not controversial,” and the most general facts about x-risk and democracy’s pathologies are well-established and not controversial (ibid.; Rawls, 2005: 67). To be sure, many of the relevant details are up for debate: exactly how probable different existential catastrophes are (and thus exactly how high total x-risk is); exactly how strongly different institutional determinants incentivize short-termism; whether certain putative x-risks (for instance, value-misaligned artificial intelligence) do in fact count as x-risks; and so on.Footnote 21 But the parties need not know any such details to doubt democracy’s x-risk-mitigating capacities. They need only know that there exist at least some x-risks which pose a non-negligible threat to both present and future generations, that democratic decision-making is compromised by several pathologies, and—a fairly weak modal claim—that some liberal but non-democratic systems which do not share these pathologies to the same extent may be less pathologized overall than democracy itself.Footnote 22 So long as they know those things, they know enough to know that it is doubtful whether democracy always minimizes x-risk.

The parties must agree upon principles of justice which they would want all previous generations to have followed. Since they “have no information as to which generation they belong,” and since “the different temporal position of persons and generations does not in itself justify treating them differently,” the parties cannot neglect the long term (which may turn out to be their own short term) or have any pure time preference whatsoever (Rawls, 1999: 118, 259). “[Q]uestions of social justice arise between generations as well as within them,” because society is a “fair system of social cooperation between free and equal citizens from one generation to the next” (ibid.: 118; Rawls, 2001: 133). The parties cannot ignore such questions.

The only question of intergenerational justice which Rawls explores in any detail relates to a just savings principle which “insures that each generation receives its due from its predecessors and does its fair share” to maintain just institutions and preserve their material base for future generations (Rawls, 1999: 254). Rawls also briefly mentions “the conservation of natural resources” and “a reasonable genetic policy” as other questions of intergenerational justice (ibid.: 118–119). He does not mention x-risk and in fact seems to suggest that humanity can expect perpetual economic and technological progress.Footnote 23

Notwithstanding, it seems as though x-risk mitigation is a central question of intergenerational justice and that the parties would therefore be greatly concerned to mitigate x-risk. Since the life of a people is “a scheme of cooperation spread out in historical time,” every generation must “carry [its] fair share of the burden of realizing and preserving a just society” (ibid.: 257). Of course, a just society can scarcely be preserved for future generations if humanity itself has been wiped out or consigned to permanent dystopic conditions in which citizens’ fundamental interests in developing their moral powers are impossible to realize. And no generation would want its own total x-risk to be excessively high due to previous generations’ negligence. Presumably, then, each generation’s duty to future generations includes a duty of some kind to mitigate x-risk. So the parties can hardly ignore the need for x-risk mitigation.

Indeed, x-risk would likely be among the most important problems in the parties’ deliberations. In an often overlooked remark, Rawls acknowledges a (zeroth) principle of justice lexically prior to the first principle “requiring that citizens’ basic needs be met, at least insofar as their being met is necessary for citizens to understand and to be able fruitfully to exercise [their] rights and liberties” and thereby develop their two moral powers (Rawls, 2005: 7). Such a principle is necessary because the two principles’ own requirements are worthless if citizens’ basic needs are not being met: “The realization of [citizens’ higher-order] interests may necessitate certain social conditions and degree of fulfillment of needs and material wants” (Rawls, 1999: 476). But x-risk threatens the provision of citizens’ basic needs, as well as their very lives. It therefore threatens not only their material interests but also their fundamental moral interests in developing their moral powers.Footnote 24 Each generation will want previous generations to have done what they reasonably could to mitigate this threat. So—by Rawls’ own lights—the parties must be greatly concerned to mitigate x-risk, for doing so is necessary to ensure that the fundamental interests of citizens across countless generations can be realized.

Note, too, that x-risk is a problem of justice not just between but also within individual generations—including whichever generation the parties themselves ultimately represent.Footnote 25 Recall that Ord estimates total x-risk within the next century to be roughly 1 in 6—a figure which can scarcely be expected to decrease over time without effective x-risk mitigation. Even if Ord’s estimate is too high, no generation facing total x-risk within an order of magnitude of 1 in 6 would want to follow principles of justice which hindered its own x-risk-mitigating capacities. Plausibly, then, the parties would be greatly concerned to mitigate x-risk even if they set aside questions of intergenerational justice.Footnote 26

What then? If the parties are greatly concerned to mitigate x-risk, and if they know that it is doubtful whether democracy always minimizes it, then they have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice, thereby ruling in at least some other political systems which may better mitigate x-risk as possibly just. More precisely, in a pairwise comparison between the two principles of justice and an experimentalist conception of justice which revises the two principles by removing the requirement of equal political liberty, the parties have reason to choose the experimentalist conception (Rawls, 1999: 106–107). (Whether they have reason to agree upon even further revisions to the two principles is a separate question which we briefly consider in Section 6. Our argument neither requires nor precludes any such revisions.)Footnote 27

Importantly, by rejecting democracy as a requirement of justice, the parties would not rule in what Rawls calls “autocratic and arbitrary forms of government”—only non-democratic systems regulated by the experimentalist conception of justice which satisfy all the two principles’ requirements besides equal political liberty (including liberty of conscience, fair equality of opportunity, and the like).Footnote 28 The parties have reason to rule in such systems if they have reason to doubt whether democracy always minimizes x-risk. So they have reason—though (again) not necessarily all-things-considered reason—to reject democracy as a requirement of justice.

Strikingly, Rawls himself concedes something like this point when he argues—very much in the spirit of experimentalism—that his theory of justice can (and must) rule in multiple economic systems:

[M]arket institutions are common to both private-property and socialist regimes…. Which of these systems … most fully answers to the requirements of justice cannot, I think, be determined in advance. There is presumably no general answer to this question, since it depends in large part upon … [each country’s] particular historical circumstances. (ibid.: 242)

No doubt, Rawls’ approach to the justice of economic systems is markedly different from his approach to the justice of political systems, since he offers multiple non-instrumental arguments for the justice of one political system—democracy—and no comparable arguments for the justice of any economic system.Footnote 29 But setting this difference aside, Rawls’ point about economic systems—which, as we shall see, he also makes about constitutional devices—seems to apply to political systems as well.Footnote 30 As we have already suggested, the parties may not be able to determine in advance which political system is most just. Among other things, the answer may depend in large part on the specific nature of each society, something they themselves cannot know (ibid.: 134). In that case, however, the parties have reason to rule in at least some liberal but non-democratic systems so as not to rule out any system which may turn out best for some societies. The alternative, after all, is to rule out political systems whose x-risk-mitigating capacities may benefit entire societies. And that (ceteris paribus) seems clearly irrational.

Importantly, our argument follows the exact specifications which Rawls lays out for a successful argument against an equal basic liberty. Rawls thinks that the two principles are operative for societies “under favorable circumstances” in which the “social conditions and level of satisfaction of needs and material wants” required for the realization of citizens’ fundamental interests have been attained (ibid.: 215, 476). Under less favorable circumstances, however, Rawls acknowledges that it may be necessary to suspend some of the first principle’s requirements—including equal political liberty itself—and move partly or entirely towards a more general conception of justice which does not prioritize the equal basic liberties (ibid.: xx, 54–55). Rawls acknowledges this possibility because he thinks that “the feasibility of the basic liberties depends upon circumstances” (ibid.: 217–218). Although he aims to develop a conception of justice for a liberal and democratic regime, Rawls concedes that a variety of circumstances can justify restrictions of liberty—not just “historical and social contingencies” but also “the natural features of the human situation” and “the more or less permanent conditions of political life” (ibid.: 215).

Rawls therefore lays out specific requirements for a successful argument against an equal basic liberty like equal political liberty: such an argument must show that the relevant inequality would be “to the benefit of those with the lesser liberty” and that it would be “accepted by the less favored in return for the greater protection of their other liberties” and fundamental interests in developing their moral powers (ibid.: 203–204). Accordingly, we argue that rejecting the requirement of equal political liberty is plausibly to the benefit of citizens potentially granted lesser political liberty in return for the greater protection of their other liberties, fundamental interests, and very lives. Equal political liberty is “subordinate to the other freedoms,” and even if it were not, citizens’ fundamental interests in developing their moral powers can hardly be realized without the bare necessities of life (ibid.: 205). Consequently, if citizens potentially granted lesser political liberty can better protect their fundamental interests by forfeiting their claim to political equality, it is likely to their benefit to do so.Footnote 31 Plausibly, they can, since x-risk threatens their fundamental interests and since it is doubtful whether democracy always minimizes it. So citizens potentially granted lesser political liberty have reason to forfeit their claim to political equality—in which case the parties in the original position have reason to reject equal political liberty as a requirement of justice.

Note, in closing, that political inequality regulated by the experimentalist conception of justice—experimentalist political inequality—does not say anything against citizens’ equal moral status. Rawls holds that the basis of citizens’ equality is specifically their possession “to the essential minimum degree” of the moral powers necessary for social cooperation (Rawls, 2001: 20 (emphasis added)). But experimentalist political inequality itself does not say anything against the minimal sufficiency of citizens’ moral powers. It does not deny their minimally sufficient ability to “honor the fair terms of social cooperation,” be “economically independent and self-supporting,” or otherwise exercise their capacity for a sense of justice and pursue their conceptions of the good (ibid.: 156–157). It denies only the necessary optimality of equal political liberty for one specific and complex political problem: x-risk mitigation. So it does not say anything against citizens’ equal moral status.Footnote 32

4 Rawlsian objections

It is worth addressing some possible objections on Rawls’ behalf to our interpretation of his theory.

First, Rawls proposes principles of justice for partly idealized well-ordered societies in which almost “[e]veryone is presumed to act justly and to do his part in upholding just institutions” (Rawls, 1999: 8). But such societies are quite different from actual societies; well-orderedness is “plainly a very considerable idealization” (Rawls, 2001: 9). It might therefore be objected that well-ordered societies would not themselves be pathologized by ignorance, irrationality, or short-termism.

We freely concede that citizens of well-ordered democratic societies would be marginally less ignorant, irrational, and short-termist. But they would still be significantly ignorant, irrational, and short-termist—as Rawls himself seems to recognize:

I also suppose that men suffer from various shortcomings of knowledge, thought, and judgment. Their knowledge is necessarily incomplete, their powers of reasoning, memory, and attention are always limited, and their judgment is likely to be distorted by anxiety, bias, and a preoccupation with their own affairs. … [T]o a large degree, [these defects] are simply part of men’s natural situation. (Rawls, 1999: 110)

In Rawls’ view, the parties must reckon with “the laws of human psychology” and the human propensity to ignorance, irrationality, short-termism, and other cognitive defects (ibid.: 119). Otherwise, they cannot agree upon practical and realistically utopian principles of justice (Rawls, 2001; 13; Rawls, 2005: 9). So they must assume that even citizens of well-ordered societies would be significantly ignorant, irrational, and short-termist.

Importantly, this reply fully comports with Rawls’ own (often misunderstood) approach to idealization in his theory of justice. Although Rawls’ theory is an ideal theory, Rawls specifically circumscribes the extent of its idealization to the one idealizing assumption of well-orderedness. Besides this one idealizing assumption, he intends his theory to be realistic and to “fall under the art of the possible” (Rawls, 2001: 185). As John Simmons puts the point, Rawls aims to give an account of “a ‘realistic utopia,’ that is, the best we can realistically hope for, ‘taking men as they are and laws as they might be’” (Simmons, 2010: 10). (Accordingly, a somewhat more precise statement of our central claim is this: If the parties are greatly concerned to mitigate x-risk, and if they know that it is doubtful whether well-ordered democracy always mitigates it better than every well-ordered non-democratic political system, then they have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice.)

Second, we have seen that the two principles of justice (including equal political liberty) are operative only under favorable circumstances. But since the threat of x-risk is universal and permanent, circumstances are arguably never favorable, because even affluent societies face serious risks of extinction or civilizational collapse. It might therefore be objected that considerations of x-risk do not count at all against equal political liberty, since they presuppose unfavorable circumstances in which the two principles themselves are not even operative.

But Rawls cannot deny that the relevant social circumstances are sometimes favorable. For he not only intends the two principles to “govern social and economic inequalities in democratic regimes as we know them” [emphasis added] but also “assume[s] as sufficiently evident … that in our country today reasonably favorable conditions do obtain” (Rawls, 2001: 43; Rawls, 2005: 297).Footnote 33 Undeniably, then, Rawls believes that circumstances in modern democratic societies can be favorable even if these societies have not yet effectively mitigated x-risk. (Recall that Rawls’ own society was well aware of at least one x-risk—nuclear holocaust—which it had not only failed to minimize but also arguably exacerbated.)Footnote 34 So our argument still stands, because it shows that the parties have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice even under paradigmatically favorable circumstances.Footnote 35

Third, Rawls holds that a conception of justice cannot violate “the constraint of the strains of commitment” by permitting unacceptable social positions which do not guarantee our fundamental interests as free and equal citizens in developing our moral powers (Rawls, 2001: 103). It might be objected that the experimentalist conception of justice violates this constraint by permitting unacceptable social positions of lesser political liberty.

In Rawls’ view, however, a conception of justice violates the constraint of the strains of commitment only if it permits social positions which do not guarantee citizens’ interests in developing their moral powers. Rawls argues that the parties “must take the strains of commitment into account” specifically because they must be confident that citizens will stably endorse their agreed-upon conception of justice as a conception which secures “every one’s fundamental interests” (ibid.: 128). And our argument for the experimentalist conception of justice is precisely that it does secure everyone’s fundamental interests—exactly what Rawls says a conception of justice should do. Absent some independent further objection, then, Rawls cannot maintain that the experimentalist conception violates the constraint of the strains of commitment.

Fourth, Rawls says that the parties in the original position are “required to agree unanimously” upon a conception of justice (Rawls, 1999: 106). There is a sense, then, in which not only the two principles of justice but also Rawls’ contractarian method itself are deeply democratic. It might therefore be objected that our argument runs contrary to the spirit of Rawls’ theory.

Undeniably, the requirement of unanimous agreement among the parties in the original position does reveal a sense in which Rawls’ method is deeply democratic. But that sense is not that Rawls’ method necessarily aims for a conception of justice which distributes political liberties equally. Instead, it is that it aims for a conception of justice which can be generally (or even unanimously) endorsed by citizens despite their “widely different and even irreconcilable” religious and other comprehensive doctrines (Rawls, 2001: 34). Rawls’ goal is a conception of justice which “all citizens as reasonable and rational can endorse from within their own comprehensive doctrines” (ibid.: 29). In principle, however, such a conception of justice need not be democratic. In principle, citizens holding different comprehensive doctrines could unanimously endorse some non-democratic conception of justice.Footnote 36 The essential object of general agreement, for Rawls, is a specific conception of justice itself—not a specific distribution of political liberties.

But if citizens even of well-ordered societies would be significantly ignorant, irrational, and short-termist, why not give up altogether on Rawls’ democratic contractarian method? The most important answer to this question is that we ourselves recognize the value of the contractarian goal of general agreement upon a conception of justice. Rawls writes, “Since the self is realized in the activities of many selves, relations of justice that conform to principles which would be assented to by all are best fitted to express the nature of each” (Rawls, 1999: 495). We do not doubt the value of a generally agreed-upon conception of justice which expresses citizens’ communal nature by gaining their general assent. Neither do we doubt citizens’ ability to agree upon such a conception. We doubt only their ability always to agree upon optimal x-risk-mitigating measures through democratic political processes. This doubt, we contend, is reasonable and does not require us to give up on a contractarian method like Rawls’ which aims for general agreement upon a conception of justice.

Fifth, and lastly, the two principles of justice are adopted and applied in a four-stage sequence, including a second “stage of the constitutional convention” following the first stage of the original position at which “rational delegates … guided by the two principles of justice” agree upon a democratic constitution which is “most likely to lead to a just and effective legal order” (ibid.: 173, 314; Rawls, 2001: 48). This constitution may limit “the scope and authority of majorities” by incorporating judicial review, supermajority requirements, and other constitutional devices which restrict the extent of equal political liberty for the sake of “the greater security and extent of the other liberties” (Rawls, 1999: 197, 201). Arguably, some such constitutional devices might significantly improve x-risk mitigation. It might therefore be objected that the parties in the original position should simply defer the problem of x-risk to the constitutional stage (at which delegates can agree upon constitutional devices which optimize x-risk mitigation) rather than considering rejecting the requirement of equal political liberty altogether.

We do not deny that some constitutional devices could improve democratic x-risk mitigation to a degree. But since the two principles significantly restrict the range of just institutional arrangements, “delegates to a constitutional convention have far less leeway” than the parties in the original position themselves, and there is no particular reason to think that any institutional arrangement within the narrow range open to these delegates’ consideration would minimize x-risk (Rawls, 2005: 340). Actual democratic constitutions differ widely and incorporate various constraints on bare majority rule, and yet most contemporary democracies do next to nothing to mitigate x-risk. Furthermore, as we argue in Section 5.2, even democratic reforms specifically designed to counteract pathologies like short-termism are unlikely to be very successful. It is therefore doubtful whether any democratic institutional arrangement would always minimize x-risk. So the parties in the original position still have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice rather than deferring the problem of x-risk to the constitutional stage.

In fact, what Rawls says about the constitutional stage only reinforces our case for experimentalism, for Rawls’ own approach to constitutional design is recognizably experimentalist. Rawls assumes that a just constitution will incorporate a bill of rights and other such “traditional devices of constitutionalism” (Rawls, 1999: 197). But he also holds that the question “which constraints work best in given circumstances to further the ends of liberty … lie[s] outside the theory of justice” itself, which “need not consider which if any of the constitutional mechanisms is effective in achieving its aim” (ibid.: 201). Many constitutional essentials “can be specified in various ways,” and their optimal specification often depends on a given society’s existing (and ever-changing) circumstances (Rawls, 2005: 228).Footnote 37 Hence, Rawls offers little more than a bare and “extremely abstract” outline of the specification of most constitutional essentials (ibid.: 340).

We agree with Rawls that “the most appropriate design of a constitution is not a question to be settled by considerations of political philosophy alone, but depends on understanding the scope and limits of political and social institutions and how they can be made to work effectively” under various circumstances” (ibid.: 408–409). We only add the following: The most appropriate distribution of political liberties is not necessarily a question to be settled by considerations of political philosophy alone—for much the same reasons. Just as the question which constitutional devices best secure citizens’ fundamental interests lies outside a theory of justice itself, so too may the question which distribution of political liberties best secures those interests. For (among other things) both questions involve complex, long-term problems like x-risk.

Again, we do not claim that the parties should reject the requirement of democracy all things considered. But we do claim that the considerations which we have put forward in favor of doing so cannot be easily outweighed. X-risk threatens the fundamental interests of both present and future generations. If some liberal but non-democratic systems might mitigate x-risk better than democracy, then the parties have significant reason to rule in such systems by rejecting democracy as a requirement of justice.

5 Other objections

Two other objections to our argument merit further discussion. The first—the objection from epistemic democracy—is that voter ignorance does not significantly compromise democratic decision-making and that democracies can actually outperform other political systems by drawing upon the collective intelligence of crowds. The second—the objection from democratic reform—is that suitably reformed democracies would always minimize x-risk even if actual democracies do not.

5.1 The objection from epistemic democracy

We have argued that democratic decision-making is compromised by voter ignorance, both generally and specifically with respect to x-risk. Epistemic democrats, however, resist this conclusion, claiming that individually ignorant agents can still make collectively intelligent decisions under the right conditions (Goodin & Spiekermann, 2018).

Some epistemic democrats appeal to Condorcet’s jury theorem, arguing that democratic collectives can make intelligent decisions so long as their members vote sincerely and independently with a probability greater than 0.5 of voting for the “correct” outcome (ibid.: 17–22). Others argue that larger and more diverse decision-making groups can epistemically outperform smaller and less diverse groups, even if the latter are made up of experts (Landemore, 2013; Page, 2007). Since the larger and more diverse groups can draw upon the distributed knowledge of their members more effectively, they can know more collectively than the smaller groups of experts—even if every individual expert knows more than every individual non-expert. Less ambitiously, some epistemic democrats argue that voters can use heuristics to overcome their political ignorance by learning from political parties, opinion leaders, traditional and online media, and other sources (Popkin, 1991). If such heuristics are sufficiently simple and reliable, uninformed voters can use them to make competent political decisions by tracking the beliefs of others who are better-informed.

If epistemic democrats’ claims on behalf of democracy are correct, then we have overstated the extent to which voter ignorance pathologizes democracy. It seems to us, however, that these claims are overly optimistic. Let us take each of them in turn.

First, voting in the real world is nothing like voting in accordance with Condorcet’s jury theorem, which requires not only voter independence and sincerity but also a minimum threshold of voter competence higher than the available evidence warrants. It is likely false that most voters have a probability greater than 0.5 of voting for the correct outcome with respect to many important political issues—including x-risk itself.Footnote 38 Indeed, some evidence suggests that voters are systematically mistaken about many important political and economic issues (Caplan, 2007: 9–11, 23–49). Even if they are not, the correct outcome with respect to a given political issue is often not even on the ballot anyway. And in most cases, no outcome addressing x-risk is on the ballot at all.

Second, although some larger and more diverse groups can epistemically outperform smaller and less diverse groups, not all such larger groups can. A minimum threshold of competence among members of larger groups is necessary for them to outperform smaller groups epistemically, and the available evidence suggests that democracies do not meet this threshold (Brennan, 2016: 182–185). In theory, of course, democracies can draw upon the wisdom of crowds. In practice, however, they often do not. And even if they always did, some smaller and less democratic groups of experts might still epistemically outperform them and thus better mitigate x-risk.

Third, and lastly, although some heuristics may be reliable, many voters’ heuristics are clearly unreliable. Most obviously, political parties often pander to voters’ misconceptions rather than reliably tracking the truth, and both traditional and online media often fail to report facts reliably or even spread misinformation (Benkler et al., 2018; Gibbons, 2023). Naturally, voters do sometimes have access to reliable heuristics. But determining which heuristics are reliable is a costly and demanding task which many voters refrain from undertaking just as they refrain from becoming politically well-informed in general. In fact, as models of rational irrationality suggest, voters often choose heuristics for reasons unrelated to their reliability, such as their entertainment value or congruence with voters’ pre-existing views (Somin, 2013: 90–118). So the very same ignorance and irrationality which prevent most voters from forming rational beliefs in the first place also plausibly prevent them from identifying and using reliable heuristics.

But maybe epistemic democrats need only appeal to comparisons of contemporary democracies with contemporary non-democracies on several important fronts to show that democracy can be expected to minimize x-risk. It is sometimes argued that democracy deals with climate change better than other political systems (Fiorino, 2018). And contemporary democracies are also wealthier than contemporary non-democracies, less prone to famine, and so on (Acemoglu et al., 2019; Sen, 1999). Perhaps, then, epistemic democrats can argue that democracy can be expected to outperform other political systems with respect to x-risk simply because it outperforms them in general.

For at least two reasons, however, we doubt whether contemporary democracies’ superior performance significantly undercuts our argument. First, attributions of democracies’ superior performance specifically to their democratic institutions are often controversial. Many scholars attribute contemporary democracies’ peace and prosperity not to their democratic institutions themselves but rather to their broadly liberal ones (Hegre, 2014; Oneal & Russett, 1999). In a similar vein, Stefan Wurster argues that democracies’ superior performance with respect to climate change is at best restricted to adaptations to “area-restricted environmental problems and those that are technically easy to solve” (Wurster, 2013: 89). Such problems, of course, do not resemble the area-unrestricted and technically complex problem of x-risk.

Second, and even more importantly, contemporary democracies’ superior performance to contemporary non-democracies—most of which are authoritarian regimes—hardly entails their superior performance to all possible non-democratic systems regulated by the experimentalist conception of justice. Even if contemporary democracies outperform contemporary authoritarian regimes—something we do not deny—the possibility remains that democracy’s x-risk-mitigating capacities are at least sometimes suboptimal relative to those of some liberal but non-democratic systems. Since the parties cannot rule out such a possibility, they still have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice.

5.2 The objection from democratic reform

Even if contemporary democracies do not minimize x-risk, it might be objected that suitably reformed democracies could do so. Maybe the right democratic reforms could counteract democracy’s pathologies. If so, then the parties in the original position would no longer have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice, since they could ensure x-risk minimization simply through democratic reform.

For example, democratic theorists have proposed several reforms to counteract democratic short-termism. First, constitutions could be amended to include provisions safeguarding future generations’ interests (González-Ricoy, 2016). Among other things, such provisions could safeguard those interests by penalizing policymakers who violate them (ibid.: 170). Second, and in conjunction with the first proposal, ombudsmen could be selected to ensure that policymakers do not violate constitutional provisions safeguarding future generations’ interests (Beckman & Uggla, 2016). Third, quotas could be imposed on legislative bodies requiring a certain proportion of younger representatives, with the expectation that such representatives would prioritize long-term issues more (Bidadanure, 2016). Fourth, voting could be weighted by age, so that younger citizens’ votes were weighted more heavily than those of older citizens (van Parijs, 1998). Assuming that legislators were at least somewhat responsive to the political preferences of the young (and that those preferences were in fact more long-termist), age-weighted voting could make democracies more long-termist by increasing younger voters’ political influence. Fifth, legislative bodies could be set up whose members were selected at random from the general population (MacKenzie, 2016). Free from short-termist electoral pressures, and guided by expert advice, such bodies could effectively counterbalance more short-termist electoral bodies. Sixth, and relatedly, legislative bodies could be set up with specific mandates to represent the interests of the young and (by extension) future generations (John, 2023).

We do not deny that reforms like these could counteract democratic short-termism to some degree. But we doubt whether they could always optimize democratic x-risk mitigation—if only because they fail to account sufficiently for the effects of voter ignorance and irrationality on democratic decision-making. This failure is unfortunate but perhaps unsurprising, since almost every proposal in the literature on long-termist reforms presupposes democracy’s necessity for long-termist politics without considering the possible advantages of non-democratic long-termist reforms. This presupposition, of course, is ill-advised, since there is no reason to rule out in advance the possibility that some non-democratic systems might counteract short-termism—and therefore mitigate x-risk—better than democracy.

Consider first a democracy reformed in accordance with the first and second proposals listed above, so that its constitution is amended to include provisions safeguarding future generations’ interests and ombudsmen for future generations are selected. Even if such a democracy would be more long-termist than contemporary democracies, there is no particular reason to think that it would deal with x-risk or other long-term problems optimally. Without further measures to counteract political ignorance and irrationality, it might do little more than replace ignorant and irrational short-termism with ignorant and irrational long-termism. Plausibly, a greater regard for the future is necessary but itself insufficient for x-risk minimization. Our goal, after all, is not that political systems attempt to mitigate x-risk but that they mitigate x-risk well.

Next, consider a democracy reformed in accordance with the third and fourth proposals, so that youth quotas are imposed on its legislative bodies and younger citizens’ votes are weighted more heavily. Even if we grant that younger citizens’ political preferences are more long-termist than those of older citizens, the point still remains that a greater regard for the future is itself insufficient for effective long-termist policy. Whether or not younger citizens’ political preferences are more long-termist, it is the quality of their preferences that matters most. Since most younger citizens (like most citizens in general) are ignorant and irrational, increasing their political influence hardly guarantees better long-term political outcomes. Moreover, both youth quotas and age-weighted voting clearly violate equal political liberty. So the possible effectiveness of these reforms scarcely counts against our argument that the parties have reason to reject that requirement.

Lastly, consider a democracy reformed in accordance with the fifth and sixth proposals, so that legislative bodies are set up whose members are randomly selected from the general population and which have specific mandates to represent future generations’ interests. Of the six proposals listed above, we suspect that these two would best counteract voter ignorance and irrationality, since they could expose selected citizens to expert feedback and sustained and focused deliberation (Fishkin, 2009). Nonetheless, at least two problems remain with them. First, the legislative bodies these proposals call for would have only limited, chiefly advisory powers. Second, and more importantly, such bodies would not necessarily outperform other legislative bodies whose members met more demanding non-democratic selection requirements. It is possible that legislative bodies which screened out especially ignorant and irrational citizens could outperform those which failed to do so—both generally and specifically with respect to x-risk. So it is doubtful whether democracies reformed in accordance with these two proposals would always minimize x-risk.

To be sure, the list of proposed long-termist democratic reforms we have considered here is far from exhaustive.Footnote 39 Nevertheless, our discussion of this list reveals a common recurring flaw in such proposed reforms: a failure to account sufficiently for the effects of voter ignorance and irrationality on democratic decision-making. This recurring flaw makes it doubtful whether democracies reformed in accordance with such proposals would always minimize x-risk.

6 Conclusion

We have argued that democratic decision-making is compromised by at least three pathologies—voter ignorance, voter irrationality, and short-termism—which hinder democracy’s capacity to mitigate x-risk. Since it is possible that some other political systems are not comparably pathologized, it is doubtful whether democracy always minimizes x-risk. So the parties in the original position have reason to reject the requirement of democracy in favor of political experimentalism, an approach to political justice which permits experimentation with at least some non-democratic political systems which might better mitigate x-risk.

We have argued here only for the possible rejection of democracy as a requirement of justice. But other arguments analogous to ours might prompt further revisions to Rawls’ theory. If some of the two principles’ requirements besides equal political liberty also hinder x-risk mitigation, then the parties may have reason to reject those requirements as well. Furthermore, since x-risks themselves are not the only threats to citizens’ fundamental interests in developing their moral powers, other grave (but not necessarily existential) risks—for instance, of war or climate change—may also prompt revisions to Rawls’ theory of justice.Footnote 40 (These may include revisions not only to the two principles themselves—Rawls’ theory of social or national justice—but also to his broader theory of international justice, since most grave risks, and all x-risks, are supranational in their potential impact.)Footnote 41

More importantly, the thrust of our argument here is not restricted by our focus on Rawls’ theory itself. Though we have argued only that the parties in the original position have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice, the essence of our argument does not flow narrowly from controversial or idiosyncratic aspects of Rawls’ description of the original position. Instead, it flows broadly from some of Rawls’ most fundamental, plausible, and widely shared normative commitments along with the relevant general facts about x-risk and democracy. First and foremost among these commitments is one to the importance of people’s lives and basic needs to their fundamental interests—a commitment shared by Rawlsians and non-Rawlsians alike. Accordingly, our challenge to Rawls—and to all of us—is not to revise our fundamental normative commitments but to incorporate the relevant general facts about x-risk and democracy into our respective theories of justice. Almost all of us share a commitment to the importance of people’s lives and basic needs to their fundamental interests. So almost all of us have at least some reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice in favor of political experimentalism.

Notes

For the sake of simplicity, we use “democracy” to refer to any political system which grants citizens equal political liberty—roughly, any system with equal and universal suffrage.

Rawls’ argument from self-respect is his most important argument for equal political liberty. For further discussion, see, inter alia, Krishnamurthy (2013).

For an overview of different definitions of x-risk, see Torres (2023).

Rawls holds that we all have higher-order—indeed, fundamental—interests in developing and exercising these two moral powers by judging the justice of our societies’ distributions of liberties and advantages and by rationally pursuing our conceptions of the good. Naturally, we cannot do either of these things if we are dead or permanently consigned to dystopic conditions. See Rawls (1999: xiii; 2001, 192).

For relevant discussion, see Ord (2020:167) and Bostrom and Ćirković (2008).

See also Caplan (2008).

Although we focus on these three pathologies as some of the clearest examples of democracy’s pathologies, we do not claim that they are the only such pathologies. As Alex Guerrero argues, decision-making in electoral democracies is compromised by the frequent “capture” of democratically elected officials by powerful special interests who seek to influence policymaking to their own benefit at the general public’s expense (Guerrero, 2014). It is also compromised by democratically elected officials’ greater-than-average susceptibility to certain framing effects, unstable tendencies to engage in risky behavior, and other cognitive biases (Sheffer et al., 2018). If some non-democratic political systems might counteract pathologies like political capture and cognitively biased governance better than democracy, then we have further reason to doubt whether democracy is always best suited to deal with problems like x-risk.

For an overview of the empirical literature on political ignorance, see, inter alia, Somin (2013).

Of course, legislators are not fully responsive to voters’ preferences. But voters still exert some influence over laws and policies. For further discussion, see Achen and Bartels (2016: 318-39).

It might be objected that democracy’s failure to prioritize x-risk mitigation does not count against it since many x-risks (like the risk of stellar explosion) cannot currently be mitigated. But even if some x-risks cannot currently be mitigated, others still can be, and it is doubtful whether democracy minimizes even these risks. Moreover, a robust x-risk mitigation strategy plausibly includes efforts to develop new capacities to mitigate currently unmitigable risks, and most democracies fail to do even that.

Rawls says that a theory of justice itself cannot tell us which constitutional devices or even which economic system is best. In all likelihood, then, he would also say that a theory of justice itself cannot tell us which specific approach to political experimentation is best. For further discussion, see Sections 2 and 3.

For a list of these requirements, see Rawls (2001: 42-44).

For one example of a hybrid political system, see Berggruen and Gardels (2013).

Indeed, it is possible that democracy itself minimizes some individual x-risks under some circumstances.

Doubtless, some putative x-risks are controversial. But others—asteroid impacts, nuclear holocausts, engineered pandemics—are not controversial, and so the parties can and must take them into account. For relevant discussion, see MacAskill (2022: 105-120).

Note that these three claims differ considerably from “comprehensive religious and philosophical doctrines,” “elaborate economic theories of general equilibrium,” and other highly disputed claims which Rawls argues the parties cannot take into account in their deliberations. See Rawls (2005: 224-225).

Rawls seems to endorse Alexander Herzen and Kant’s view that later generations enjoy better fortunes than earlier ones. Hence, his sketch of a just savings principle never addresses the possibility that future generations might be worse off than previous ones. But such a possibility certainly exists—as Rawls’ own references to questions of conservation and genetic policy themselves presuppose (ibid.: 254-256).

Hence, our argument is not utilitarian: It does not dispute the inviolability of the basic rights Rawls grants individual citizens besides equal political liberty or the moral seriousness of “the distinction between persons.” It contends that the parties would be greatly concerned to mitigate x-risk not in order to maximize aggregate well-being but in order to safeguard individual citizens’ fundamental moral interests—first and foremost, by safeguarding their very lives (ibid.: 24).

On Rawls’ “present-time-of-entry interpretation of the original position,” the parties represent citizens who are contemporaries and members of a single generation whose “place among the generations” they do not know. It is for this reason that they must agree upon principles of justice which “the members of any generation … would adopt as the principle[s] they would want preceding generations to have followed, no matter how far back in time” (Rawls, 2001: 160).

Thus, among other things, our argument does not run afoul of the non-identity problem: the problem of evaluating actions which benefit or harm future people but also change which (and in some cases how many) future people will exist. Since the parties do not represent all possible citizens—only a single (and not merely possible) generation—it might be objected that they would not be concerned to mitigate x-risk because x-risk specifically threatens merely possible people who will never even exist because of it. But this objection fails. Rawls conceives society as a scheme of cooperation spread out in historical time in which no generation can “formulate principles [of justice] especially designed to advance its own cause” (Rawls, 1999: 121). He therefore holds that obligations to future generations arise not from obligations to specific future individuals (whom the parties cannot identify) but from the nature of social justice itself, which requires egalitarian cooperation across both space and time. Plausibly, imparting increasingly high probabilities of existential catastrophe to successive future generations runs contrary to the spirit of such intergenerational cooperation. So the nature of social justice itself requires the parties to be greatly concerned to mitigate x-risk. For further discussion, see Parfit (1984: 349-378), Reiman (2007), and Karnein (2022).

For an argument for more radical revisions to the two principles in an experimentalist vein, see Kogelmann (2017).

See Rawls (1999: 96).

Although it is beyond the scope of this easy to refute these arguments, we believe that they fail and that the non-instrumental considerations they adduce in favor of democracy as a requirement of justice would not outweigh considerations of x-risk against that requirement even if they succeeded. In any case, our argument does not presuppose either of those claims, since we do not claim here that the parties have reason to reject democracy as a requirement of justice all things considered.

See Section 3.

Note that the experimentalist conception of justice would still guarantee such citizens protection from any political inequalities which would harm them. Because it retains the difference principle, the experimentalist conception requires political and other social inequalities to be universally beneficial. Furthermore, because it retains fair equality of opportunity, it requires political and other social inequalities to be regulated by fair equality of opportunity. It therefore permits only political inequalities which would be beneficial to all citizens—including citizens potentially granted lesser political liberty. The reason citizens would accept it, then, is simply that it has no downside. See ibid. (478) for relevant discussion.

Compare experimentalist political inequality with judicial review, one of several constitutional devices which restrict equal political liberty and which Rawls nevertheless argues can be just. Judicial review, because it distributes judicial liberties unequally, does say something against the necessary optimality of equal judicial liberty for constitutional interpretation. But it does not therefore say anything against the minimal sufficiency of citizens’ moral powers—and so it does not say anything against their equal moral status. The same holds true, mutatis mutandis, for experimentalist political inequality. See Rawls (1999: 197).

See also Mulgan (2011: 161).

As, of course, was Rawls himself (Rawls, 2005: 354-355).

If Rawls nevertheless denies that circumstances can ever be favorable, he does so at a heavy price. For then he must concede that his theory cannot be a realistically utopian theory of justice for democratic regimes as we know them.

Thus, as Rawls himself observes, someone may accept the original position thought experiment—including the requirement of unanimous agreement among the parties—and still reject the two principles themselves. Just as there is no necessary connection between Hobbes’ contractarian method and absolutism, there is no necessary connection between Rawls’ contractarian method and democracy (Rawls, 1999: 14). See also, inter alia, Tuck (1999: xxiv-vii).

Rawls mentions “the difference between presidential and cabinet government” as an example of a difference between two possible specifications of certain constitutional essentials (ibid.).

See Brennan (2016: 179-180) for relevant discussion.

For a more thorough survey of proposed long-termist democratic reforms, see González-Ricoy and Gosseries (2016a).

See Rawls (1993) for relevant discussion.

References

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy, 127(1), 47–100. https://doi.org/10.1086/700936

Achen, C.H. & Bartels, L.M. (2016). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton.

Anderson, E. S. (1991). John Stuart Mill and experiments in living. Ethics, 102(1), 4–26.

Barrett, J. (2020). Social reform in a complex world. Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, 17(2), 103–132. https://doi.org/10.26556/jesp.v17i2.900

Beckman, L., & Uggla, F. (2016). An ombudsman for future generations: Legitimate and effective? In I. González-Ricoy & A. Gosseries (Eds.), Institutions for future generations (pp. 117–134). Oxford.

Bell, D.A. (2015). The China model: Political meritocracy and the limits of democracy. Princeton.

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics.

Berggruen, N. & Gardels, N. (2013) Intelligent governance for the 21st century: A middle way between West and East. Polity.

Bidadanure, J. (2016). Youth quotas, diversity, and long-termism: Can young people act as proxies for future generations? In I. González-Ricoy & A. Gosseries (Eds.), Institutions for future generations (pp. 266–281). Oxford.

Bostrom, N., & Ćirković, M. M. (2008). Introduction. In N. Bostrom & M. M. Ćirković (Eds.), Global catastrophic risks (pp. 1–29). Oxford.

Brennan, J. (2016). Against democracy.

Caney, S. (2016). Political institutions for the future: A five-fold package. In I. González-Ricoy & A. Gosseries (Eds.), Institutions for future generations (pp. 135–155). Oxford.

Caplan, B. (2007). The myth of the rational voter: Why democracies choose bad policies. Princeton.

Caplan, B. (2008). The totalitarian threat. In N. Bostrom & M. M. Ćirković (Eds.), Global catastrophic risks (pp. 504–519). Oxford.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Harper and Row.

Fiorino, D.J. (2018). Can democracy handle climate change? Polity.

Fishkin, J.S. (2009). When the people speak: Deliberative democracy and public consultation. Oxford.

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G., & O’Donoghue, T. (2002). Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 351–401. https://doi.org/10.1257/002205102320161311

Gibbons, A.F. (2023). Bullshit in politics pays. Episteme, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2023.3

González-Ricoy, I. (2016). Constitutionalizing intergenerational provisions. In I. González-Ricoy & A. Gosseries (Eds.), Institutions for future generations (pp. 170–183). Oxford.

González-Ricoy, I., & Gosseries, A. (2016a). Institutions for future generations. Oxford.