Abstract

Even though metaphysical dependence has been a subject of a lively debate in contemporary metaphysics, it is rare in such a debate to seriously consider the possibility that the metaphysical dependence relations among the things in the reality is inconsistent. This paper focuses on two philosophers of the Kyoto School, Kitaro Nishida and Keiji Nishitani, who challenge the common supposition that the structure of reality is consistent. In this paper, we show that Nishida’s logic of place is a version of inconsistent foundationalism, according to which absolute nothingness as a foundational element does not depend on anything but depends on itself, and that Nishtani’s theory of the field of emptiness is a version of inconsistent coherentism, according to which emptiness does not depend on anything but depends on everything else (and possibly on itself).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

We live in a world that is literally packed with all sorts of different things. There are stars and shadows. The Pollock’s paintings we admire at the museum and the chair I am using right now are also things. It is intuitive to think that many of these things metaphysically depend on other things: Their existence or being depends on other things. For their being or existence, stars depend on some specific chemical reactions, shadows of trees depend on trees, Pollock’s paintings depend on the colors used to paint them and the chair I am using right now depends on its parts. All these metaphysical dependence relations constitute, so to speak, the structure of reality.

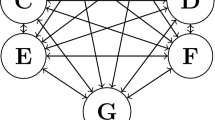

In the contemporary literature, these metaphysical dependence relations have been the subject of a lively debate — a debate that gave and still is giving rise to many different theories. Bliss and Priest (2018) provides us a useful taxonomy of these theories. In particular, according to them, these different theories are categorized into the following major clusters: atomism, foundationalism, infinitism, and coherentism. Here, we are concerned with foundationalism and coherentism. Following (Bliss & Priest, 2018), we take foundationalism to be the view according to which everything metaphysically depends on foundational elements. Foundational elements are elements that do not metaphysically depend on anything, except maybe themselves. Concerning coherentism, Bliss and Priest (2018) (we guess, not on purpose) gives us two different characterizations of it: everything depends on everything else (and possibly on itself); and everything depends on everything. We call the former weak coherentism and the latter strong coherentism.

Even though, in the current debate, there are many different accounts of metaphysical dependence relations, almost all of them have, at least, one common feature: they are consistent. In other words, besides some rare exceptions (Casati, 2017; Casati, 2018; Priest, 2017), almost all contemporary philosophers presuppose that the structure of reality is not contradictory. In this paper, being inspired by the Asian tradition, we discuss two philosophers, Nishida Kitaro and Nishitani Keiji, that seem to challenge this presupposition. Indeed, we show that they endorse some metaphysical ideas which lead to an inconsistent account of the structure of reality. To begin with, in Sect. 2, we introduce some basic formal notions that we employ in this paper. After that, in Sect. 3, we argue that, in Nishida’s philosophy, we find a form of inconsistent foundationalism (call it para-foundationalism). In Sect. 4, we argue that, in Nishitani’s philosophy, we can find a form of inconsistent coherentism (call it para-coherentism).

Before discussing these matters, let us make an important methodological remark.Footnote 1 It is important to recall that the methodology which is used in our paper has been extensively employed in the recent debate about analytic Asian philosophy. In recent years, Deguchi, Garfield, Siderits, Priest, and Westerhoff have developed a new way of merging analytic and Asian philosophy, a way from which both these traditions can benefit. We hope our paper can represent a small, but nonetheless relevant, instance for such a methodology. Our paper tries to show that key ideas from Japanese philosophy can be studied, discussed, and articulated by employing analytic philosophical tools (see, for instance, the employment of non-classical logics), and analytic metaphysics can enrich its philosophical landscape by discussing Japanese philosophy (see, for instance, the under-explored existence of inconsistent grounding structures). Our paper thus attempts to explore two under-researched paths: One path is exegetical and the other one is philosophical. This paper asks analytic metaphysical questions of grounding in relation to some texts of the Kyoto School, applying a framework that allows for inconsistent grounding to interpret key elements of Nishida’s logic of place and Nishitani’s field of emptiness. However, the paper does so without trying to give any comprehensive interpretation of Nishida and Nishitani. Moreover, we can easily imagine that many scholars might have some serious methodological concerns with the exegetical aspirations of the paper. For instance, it is not difficult to imagine that our employment of contemporary analytic philosophy and formal tools might be regarded as methodologically suspicious. This is certainly a legitimate concern. However, it is important to note that, even if our paper is deemed to be exegetically untenable, it would remain significant for the philosophical ideas which are developed by our reading of Nishida’s logic of place and Nishitani’s field of emptiness. Grounding structures are often, if not always, taken to be consistent. Drawing philosophical inspiration from these two Japanese giants, we are challenging this assumption, even though we are not committed to say that they themselves would follow us down this unexplored philosophical path.

2 A bit of formality

In this section following (Bliss & Priest, 2018), we introduce a bit of formality. First of all, we use \(x \rightarrow y\) to mean “x metaphysically depends on y.” A foundational element is defined in the following way (Bliss and Priest, 2018, p. 66):

Then, foundationalism is formulated as below (Bliss and Priest, 2018, p. 66):

Weak coherentism is the view according to which everything depends on everything else (and possibly on itself). Formally:

Strong coherentism is the view according to which everything depends on everything. Formally (Bliss and Priest, 2018, p. 66),

What has been described until now is just the background of the main ideas of this paper. In what follows, we employ the formal tools introduced above with the aim of clearly analyzing Nishida’s logic of place and Nishitani’s field of emptiness. We also argue that, in both cases, Nishida and Nishitani intentionally support an inconsistent account of the structure of reality.

3 Nishida’s logic of place

In his epoch-making article “Place (Basho;

)” (1926a), Nishida provides an interesting way of defining objecthood/being, and, based on this definition, introduces his own characterization of nothingness. In this section, we claim that (i) his theory of being (

)” (1926a), Nishida provides an interesting way of defining objecthood/being, and, based on this definition, introduces his own characterization of nothingness. In this section, we claim that (i) his theory of being (

) and nothingness (

) and nothingness (

), the logic of place, is a theory of metaphysical dependence and (ii) it is a version of inconsistent metaphysical dependence theory, more precisely, what we call parafoundationalism.

), the logic of place, is a theory of metaphysical dependence and (ii) it is a version of inconsistent metaphysical dependence theory, more precisely, what we call parafoundationalism.

3.1 The logic of place as foundationalism

Let us begin with a terminological remark. Nishida’s notion of “being” is ambiguous between “a thing which is” and “to be.” To avoid confusion, we use the term “object” to mean the former. In this terminology, “being” which means “to be” is paraphrased as “to be an object.” Note that in this terminology, “object” is used in a very broad sense. Both concrete and abstract objects are objects; merely possible and impossible objects and purely intentional objects are objects; properties, sets, or other higher-order entities are objects. Indeed, everything that is an object.

Nishida (1926a) gives us an interesting answer to the following ambitious question: What does make an object be an object? We take Nishida as, by exploring this question, addressing a general metaphysical dependence structure shared by all objects. From this point of view, Nishida is interpreted as aiming to investigate a common structure of being an object which underlies all of these different kinds of objects, like a cat is an object; the natural number 1 is an object; Pegasus is an object; a civet, as an individual animal, is an object; Viverridea, as a biological family, is an object; and Carnivora, as a biological order, is an object; and so on.

His answer to the question is simple: To be an object is to be within a place. Then, what is it to be within a place? (Nishida, 1926a) and his subsequent works give us a couple of examples of objects and places standing in the being-within relation, as Krummel (2012) lists up as follows: “the grammatical subject-predicate, the epistemological object-subject, the conceptual particular-universal, the metaphysical matter-form, the phenomenological noema-noesis, content-act, and so forth” (Krummel, 2012, p. 16). Let us focus on the first example on the list. According to Nishida, the subject of a subjunctive judgement of the form A is B is an object and its predicate is a place within which the object is. Borrowing an example from (Davis, 2017, Section 3.3), in the subjunctive judgement “red is a color,” the grammatical subject “red” (and its designation redness) as an object is subsumed in its predicate “color” (and its designation color) as a place, and the former is within the latter.

In what sense does a place make an object be an object? A place is a place of differentiation. According to Nishida, for a specific color red to be individualized, or differentiated from other colors like blue or yellow, both red and other colors are within a common place, that is, the higher order universal of being a color. As Nishida claims, “that which is not red as contrasted with red is also a color” (Takeda et al., 2002, III, p. 422, English translation, p. 55). Given that all of other colors than red are non-red, a place color “envelops” both an object red and its negation so that the differentiation of an object red from its negation emerges (Nishida claims the same holds for the distinction between being and its negation, that is, non-being, or, nothingness (

). We will see more on this latter). According to (Nishida, 1926a), this differentiation is achieved as self-determination of “universals.” An object’s being within a place is understood as “a self-determining act, its self-individualization into that particular [object]. The grammatical subject is then what is cutout through differentiation from the vast matrix that is the predicate, the universal [place]” (Krummel, 2012, p. 16).

). We will see more on this latter). According to (Nishida, 1926a), this differentiation is achieved as self-determination of “universals.” An object’s being within a place is understood as “a self-determining act, its self-individualization into that particular [object]. The grammatical subject is then what is cutout through differentiation from the vast matrix that is the predicate, the universal [place]” (Krummel, 2012, p. 16).

We will see more on self-determination and its relation to nothingness in the next subsection. At this point, we focus on Nishida’s claim that x is an object in virtue of the fact that x is within a place. We can properly treat this as a claim about metaphysical dependence. The objecthood of x is metaphysically dependent on x’s being within a place. More simply, an object metaphysically depends on a place iff an object is within a place.

Now, let us turn onto Nishida’s theory of nothingness. According to Nishida, every object is an object in virtue of being within a place, but a place itself is not an object, and thus, nothingness, with respect to the objects being within it. The following metaphor may be helpful for understanding Nishida’s point. When we watch a play, we focus on what happened on its stage. If we are asked how many things appeared and what relations are held among them in the play, we usually count only things and relations on the stage, ignoring the stage and the relations between the stage and the things on it. The stage is just a stage and does not appear as a thing at all. A place that makes an object be an object is like a stage on which many things appear and relate: A place of the objects on which we focus is just a background of them and does not appear as an object.

In this sense, a place within which an object is nothingness relative to the object. However, this does not mean that a place that makes an object be an object can never be within some other places. Indeed, when we talk about the being-within relation between an object and a place, this relation is understood as holding within a place within which both the object and the place are, and, therefore, the place is an object with respect to it. He calls a place that is within a place relative nothingness. Then, is there a place that is within no place? Nishida’s answer is yes: Nishida calls a place that is not within any place the place of true nothingness (

) or absolute nothingness (

) or absolute nothingness (

)-it is truly and absolutely nothing, since no place p makes it to be an object by embracing it within p.

)-it is truly and absolutely nothing, since no place p makes it to be an object by embracing it within p.

Exactly the same point can be made through his equation of subsumption of an subject by a predicate as an object’s being within a place. According to Nishida, there is a predicate that can never be the subject of any subsumptive judgment. He calls it the transcendent predicate and equates it with absolute nothingness,Footnote 2 Since the transcendent predicate can never be a subject of any subsumptive judgment, it can never be an object. He says:

Yet if we continually pursue this to the end in the direction of universals in subsumptive relationships, the direction of the predicate in judgements, we cannot but arrive at what I call the basho of true nothing. (Takeda et al., 2002, III, p. 467, English translation, p. 94)

Now, given that the being-within relation is a metaphysical dependence relation, absolute nothingness is ungrounded, in the sense that it does not depend on anything. It is not an object and, thus, its objecthood does not depend on anything. Formally speaking, since there is no x such that \(n \rightarrow x\), \(\forall y (n \rightarrow y \supset n = y)\) vacuously holds (where n for absolute nothingness). Therefore, absolute nothingness is a foundational element.

Moreover, Nishida claims that absolute nothingness is the fundamental reality in the sense that it makes every object be an object.Footnote 3 He says:

The true to hen [One, the terminology taken from Plotinus] must be the place of absolute nothingness, something which can never be determined as a being, within which every being is and by which every being is seen. (Takeda et al., 2002, VII, p. 224)

Given this claim, we can show that Nishida’s logic of place is a version of foundationalism as follows. Let us define \(X_0 = \{ n \}\). Then, \(X_1 = \{ x: x \in X_0\) or \(\forall y (x \rightarrow y \supset y \in X_0) \}\). The quoted passage claims that every object is depend on absolute nothingness, that is, \(\forall x (object(x) \supset x \rightarrow n)\). It follows that everything, including all objects and absolute nothingness, is in \(X_1\), that is, \(\forall x x \in X_1\). Therefore, \(X_1 = \displaystyle \bigcup _{n \in \omega } X_n = X\) and \(\forall x x \in X\).

To sum: the being-within relation is a metaphysical dependence relation. Moreover, every object depends on absolute nothingness and absolute nothingness is a foundational element which depends on nothing. Therefore, his theory of metaphysical dependence endorses foundationalism.

3.2 The logic of place as parafundationalism

As we have confirmed, Nishida’s logic of place is a version of foundationalism, but not simply so. His logic of place is an inconsistent version of foundationalism.

Recall Nishida’s claim that the differentiation of an object from other objects is the self-determination of the universal as a place within which they are. Nishida applies this principle even to the distinction between objects and nothingness as a place within which the objects are. For this distinction to hold, both objects and nothingness must be within a place. Let us explain this with an example: The color red is differentiated from other specific colors like blue within a place color. In addition to this, the color red is differentiated from the place color, and this differentiation emerges within a place which is broader than color and within which both red and color are. If we call the distinction between an object and its negation as horizontal and the distinction between an object and its place as vertical,Footnote 4 Nishida’s claim is paraphrased as follows: Any vertical distinction must be horizontalized relative to a broader place which envelops the vertical distinction. This horizontalization is also found in the distinction between all beings and nothingness as their negation. According to Nishida, absolute nothingness is the place within which this horizontalization occurs. He says:

In order to recognize that which is, we recognize it in contrast to that which is not. But that which is not, recognized in opposition to that which is, is [thus] still an oppositional being. True nothing must be that which envelops such being and nothing; it must be a basho wherein such being and nothing are established. The nothing that opposes being by negating it is not true nothing. Rather true nothing must be that which forms the background of being. (Takeda et al., 2002, III, p. 422, English translation p. 55)

This requirement of horizontalization leads to a paradox when we consider absolute nothingness as a place of all objects. Once we see the distinction between all objects and absolute nothingness within which all objects are, this distinction must be horizontalized relative to a place within which all objects and absolute nothingness are. However, absolute nothingness is the broadest place which is within no place.

Nishida describes this situation as a contradiction by taking absolute nothingness as being within itself. Absolute nothingness is a place within which it is. He calls this reflexive structure self-awareness (

) and takes it a fundamental feature of absolute nothingness. If so, absolute nothingness is a place of itself and, at the same time, is an object of itself. The place is identical to an object depending on it. Indeed Nishida says:

) and takes it a fundamental feature of absolute nothingness. If so, absolute nothingness is a place of itself and, at the same time, is an object of itself. The place is identical to an object depending on it. Indeed Nishida says:

it is possible to say that self-awareness is the identity of what envelopes and what is enveloped, the identity of a place and “a being which is within [the place]” (Takeda et al., 2002, IV, p. 337-338.)

In this way, absolute nothingness is indeed within a place. Given his definition of objecthood, it follows that absolute nothingness is an object, even though it is absolutely nothing, and thus, is not an object at all!

So, Nishida’s logic of place commits itself to the following contradiction concerning absolute nothingness: Absolute nothingness does not depend on anything; and absolute nothingness depends on something, that is, on itself. Therefore, absolute nothingness is a foundational element, but in a contradictory way: There is nothing on which absolute nothingness depends, and there is something on which it depends.Footnote 5

As a result, Nishida’s logic of place is a specific version of foundationalism: Everything grounds out in a contradictory foundational element. We call this version of foundationalism parafundationalism.Footnote 6

4 Nishitani’s theory of emptiness

4.1 Nishitani and nihilism

Nishitani Keiji, one of the most important figures belonging to the Kyoto School, is, without any doubts, a deep, original but obscure thinker. His philosophical production is, indeed, far from the concepts and the style familiar to a contemporary philosopher and this might be one of the reasons why there is much disagreement about how to interpret some of his ideas. Having said that, it is interesting to notice that there is a significant agreement on, at least, one important issue, that is, Nishitani’s concern with nihilism and, in particular, its European form. But what does he take European Nihilism to be? And why is he so concerned with it?

According to Nishitani, Nihilism questions, challenges and, finally, destroys all the religious, ethical, moral, and political values people have traditionally believed in. If so, Nihilism destabilized human beings forcing them to realize that, on the one hand, all the values or principles used to organize their lives are ungrounded and, on the other hand, their own existences are ultimately meaningless. This is also the reason why Nihilism always goes hand in hand with a feeling of deep pessimism and despair. As it is easy to imagine, European Nihilism is nothing more than that specific kind of Nihilism which, taking place in Europe, challenges European values, condemning European people to pessimism and despair. We can find these ideas in Nishitani’s The Self-Overcoming of Nihilism:

It [European Nihilism] is a crisis in the sense that people began to feel a quaking underfoot of the ground that had supported the history of Europe for several thousands of years and laid the foundations of European culture, thought, ethics, and religion. More than this, it means that life itself is being uprooted and human being itself turns into a question mark. Since the latter half of the nineteenth century, this sense of crisis or nihilism, combined with a sense of pessimism and decadence, has been attacking Europe (Nishitani, 1990, p.173).

Having said that nothing is completely lost yet. Indeed, according to Nishitani, some European thinkers have developed what he himself calls “Affermative Nihilism” or “Nihility of life,” namely a philosophy that, without failing to recognize the destructive force of Nihilism, aims at affirming both the importance of human beings and the meaning of their lives. Examples of Affermative Nihilists are Nietzsche with his willing of power and Stirner with his creative nothing. Nishitani writes:

The encounter with nihility at the base of historical actuality was the turning point in which Nietzsche’s counter-movement emerged from nihility: the shift away from a nihility of death to a nihility of life, or to what Stirner calls creative nothing. (...) [This form of] Affirmative Nihilism began to emerge from an awareness of the fundamental crisis in Europe as a way to overcome this crisis at its roots (Nishitani, 1990, p.174).

Nishitani is so concerned with European Nihilism because he thinks that, for different cultural and political reasons, Japan faces a similar issue: as Europe, Japan is subject to a form of Nihilism according to which, using his words, “the spiritual [Japanese] core, began to decay in subsequent generations until it is now a vast, gaping hollow in our ground” (1990, p.175). He sadly comments: “The various manifestations of culture at present, if looked at closely, are mere shadows floating over the void” (Nishitani, 1990, p.175). Moreover, Nishitani points out that, contrary to the European case, Japan does not seem to have the philosophical resources to transform Nihilism in what we have previously called “Affirmative Nihilism.” And the reason is that, following again Nishitani, Japan seems to be unaware of facing such a crisis. He writes: “our crisis is compounded by the fact that not only are we in it, but we do not know that our situation is critical” (Nishitani, 1990, p.177). If so, the relevance of the question posed by Nishitani should be clear: how can Japanese philosophers develop their own form of Affirmative Nihilism? How can Japanese thinkers try to develop a philosophical theory that restores the importance and meaning of human life?

Nishitani thinks that the overcoming of Japanese Nihilism requires two main steps. The first step is represented by the attempt of becoming aware that Nihilism constitutes an actual problem. Only realizing that Nihilism is threatening culture, values, and more generally, any attempt of grounding the importance of human life, philosophers can try to overcome it. Moreover, such a realization can occur by engaging with European Nihilism: studying other forms of Nihilism can help to better understand the Japanese one. He writes: “[European Nihilism] can make us aware of the nihility within – a nihility, moreover, that has become our historical actuality” (Nishitani, 1990, p.179). The second step is represented by the development of a philosophical system that can overcome Nihilism: according to Nishitani, this has to be done by finding inspiration in Buddhism and, more generally, in the history of Japanese philosophy. Japanese philosophers need “to return to [their] forgotten selves and to reflect on the tradition of oriental culture” (Nishitani, 1990, p.179).

The philosophical project outlined in the previous paragraph represents the highest aim of Nishitani’s philosophical career and, for its extraordinary importance, it deserves full consideration. However, due to the vastness and the richness of this enterprise, it would be impossible to discuss all its aspects in this paper. For this reason, focusing our attention on the second step of Nishitani’s project, we will simply consider his attempt of overcoming Nihilism by developing what he himself calls the field of emptiness [Sunyata]. More specifically, we will discuss the metaphysical features of the field of emptiness; we will also argue that, first of all, such features are inconsistent and that, secondly, Nishitani seems to accept these inconsistencies as true. Finally, we will show that the field of emptiness can be usefully described by employing the notion of “grounding.”

One final remark. The idea that Nishitani’s field of emptiness leads to overcome Nihilism is commonly accepted (see, for instance, Parkes, 2014). Having said that, there is a lot of disagreement about why the field of emptiness leads to overcome the crisis created by Nihilism. This is still a heavily discussed issue in the secondary literature and, unfortunately, this paper will not contribute to this debate. As already mentioned above, here, we work under the assumptions that, first, Nishitani’s aim in developing the field of emptiness is to overcome Nihilism and that, secondly, Nishitani believes to be successful in doing so. Consequently, we try to discuss and analyze the metaphysical features of the field of emptiness only.

4.2 The field of emptiness as coherentism

To begin with, it is important to be clear about what the field of emptiness is. According to Nishitani, the field of emptiness represents the actual structure of the world, that is, how the world really is. Thinking properly about the world means thinking that everything (for instance, our self, the pine tree, and the bamboo) is part of / has a place in the field of emptiness. In other words, in the field of emptiness, every thing (namely our self, the pine tree, the bamboo, and all the rest) appears for what it really is — for what it is in itself. Using Nishitani’s jargon, in the field of emptiness, everything (every such or that) is revealed in its suchness or thatness. The field of emptiness is “the point at which everything around us becomes manifest in their suchness” (Nishitani, 1982, p.90). As Deguchi (2014) suggested, having access to the field of emptiness is having epistemic access to the ultimate structure of reality: knowing the field of emptiness is knowing how reality actually is.

According to Nishitani, in the field of emptiness, everything is “interconnected” with everything else. “All things that are in the world are linked together” (Nishitani, 1982, p.149). In a more metaphorical way, Nishitani also claims that: “beings one and all are gathered into one, while each one remains absolutely unique in its “being,” points to a relationship in which (\(\dots \)) all things are master and servant to one another” (Nishitani, 1982, p. 148). Everything, literally everything, from the most relevant to the most insignificant thing, is interconnected with everything else. “Even the very tiniest thing, to the extent that it “is,” displays in its act of being the whole web of circuminsessional interpenetration that links all things together” (Nishitani, 1982, p.150).

The interconnection between everything and everything else makes every thing exactly what every thing is. In this sense, everything metaphysically depends on everything else: for every thing, its nature is determined by its interconnection with everything else. Appealing again to the same metaphor presented above, Nishitani writes: “[everything] lies at the ground of all the other things, making it to be what it is and thus to be situated in a position of autonomy as master of it” (Nishitani,1982, p. 148). In order to clarify this idea, consider the pine tree in front of my window. The nature of this specific pine tree — the fact that it is this specific pine tree — is determined through the interconnection with the table, the sky, number two, the Golden Temple in Kyoto and everything else. In this sense, being part of this intricate network of metaphysical dependence relations makes things exactly what they are. We can summarize this idea (call it [F\(_{1}\)]) in the following way:

[F\(_{1}\)] Every thing (and only things) metaphysically depends on everything else.

As mentioned in the Introduction, weak coherentism is taken to be the view according to which everything depends on everything else (\(\forall x \forall y\) \((x \ne y \supset x \rightarrow y)\). If so, since, in Nishitani’s field of emptiness, everything metaphysically depends on everything else, such a view can be classified as a form of weak coherentism.

At this point, it is important to specify that many interpreters argue that Nishitani’s field of emptiness is nothing more than a revival of what, in the Huayan tradition, is called the Net of Indra (Carter 2013; Deguchi, 2015). Moreover, some philosophers interpret the Indra’s net as the view according to which everything depends on everything, that is, everything depends on everything else and each thing depends on itself too (Priest, 2014, ch.11–12). Now, if we think that Nishitani’s field of emptiness is the Net of Indra and if we believe that, in the Net of Indra, everything depends on everything (and not only on everything else), then the field of emptiness is a form of strong coherentism. Indeed, in the Introduction, we define strong coherentism as the view according to which everything depends on everything (\( \forall x \forall y\) \(x \rightarrow y\)). Having said that, we believe that the quotations presented above do not support such an interpretation of Nishitani’s field of emptiness: for this reason, in the rest of this section, we stick on the interpretation that understands the field of emptiness as, at least, a weak coherentist position, and leave it open whether it is a strong coherentist position as well.

4.3 The field of emptiness as para-cohrentism

Deeply connected with Nishitani’s field of emptiness is another central concept in his metaphysics, that is, the concept of emptiness. As we have seen discussing [F\(_{1}\)], according to Nishitani, everything metaphysically depends on everything else: this means that the nature of every thing is uniquely determined by everything else. If so, no things have independent nature. Following a branch of Buddhist philosophy, Nishitani claims that everything is fundamentally empty, that is, everything is empty of its independent nature (cf. Nishitani, 1982, p. 149). But what are we talking about when we talk about something being empty? What is the emptiness we are referring to? What is emptiness per se?

Following a traditional Buddhist thought, Nishitani believes that everything is ultimately empty and, therefore, emptiness is the ultimate nature, the metaphysically deepest reality, of every thing that is part of the field of emptiness. Moreover, Nishitani describes emptiness in the following way: “the selfness [which is interpreted as emptinessFootnote 7] is laid bare as something that cannot be expressed (...) in any language containing logical form. (...) We can only express it in terms of a paradox, such as it is not this thing or that, therefore it is this thing or that” (Nishitani, 1982, p.124). Needless to say, such a characterization of emptiness is very obscure. However, following some interpreters (Deguchi, 2015), we believe that one possible way of making sense of Nishitani’s quotation is that, in this passage, Nishitani himself accepts the idea that emptiness is truly contradictory, being both a thing and not. If so, Nishitani’s emptiness has the following feature (call it [F\(_{2}\)]):

[F\(_{2}\)] Emptiness is not a thing and is a thing.

Now, of course, [F\(_{2}\)] establishes the inconsistency of emptiness itself; however, if we carefully examine both [F\(_{1}\)] and [F\(_{2}\)], we can easily see that such an inconsistency spread to the whole intricate network of metaphysically dependence relations as well. To see why, let’s begin examining what follows from the fact that Emptiness is not an entity. This is the first conjunct of [F\(_{2}\)]. According to [F\(_{1}\)], every thing (and only things) metaphysically depends on everything else. Since Emptiness is not a thing, Emptiness does not metaphysically depend in everything else. However, if we take seriously [F\(_{2}\)], Emptiness is a thing as well. This is expressed by the second conjunct of [F\(_{2}\)]. Once again, since, according to [F\(_{1}\)], every thing (and only things) metaphysically depends on everything else and since emptiness is a thing too, Emptiness depends on everything else. Therefore, since Emptiness is both an entity and not, Emptiness both depends on everything else and not. If so, Nishitani still endorses a form of weak coherentism; however, this time, it is inconsistent. It is weak coherentism because, in the field of emptiness, everything depends on everything else. It is an inconsistent form of weak coherentism because there is something, namely emptiness, that, even thought it still depends on everything else, at the same time, it does not. We label this position “para-coherentism.”

To conclude, let us specify that, here, we are not committed to defend the idea that this is exactly what is supported by Nishitani. However, we are committed to the idea that, given [F\(_{1}\)] and [F\(_{2}\)], Nishitani should have endorsed the inconsistency of the field of emptiness. If so, since the field of emptiness represents the philosophical theory that is able to overcome Nihilism, then the overcoming of Nihilism itself seems to lead to the acceptance of the inconsistent nature of the structure of reality. Accepting contradictions is the medication against the Nihilist disease.

5 Conclusion

To conclude, let us summarize what we have done. The so-called Kyoto School and, in particular, Nishida and Nishitani have the well-deserved reputation of being obscure and, therefore, difficult to be interpreted. In this paper, we have tried to present an accessible interpretation of Nishida’s logic of place and Nishitani’s field of emptiness. In doing so, we have cashed out these two complicated concepts in terms of metaphysical dependence. Moreover, we have shown that both the logic of place and the field of emptiness lead to an inconsistent structure of reality.

We are aware that, first of all, someone might disagree with our interpretations. Moreover, secondly, many questions still remain unanswered. For instance, how is the contradictory structure of Nishida’s logic of place related to his later thoughts, in particular, his enigmatic notion of absolutely contradictory self-identity?Footnote 8 How can the contradictory account of the field of emptiness help the human being to overcome Nihilism? For all these reasons, we would like to make clear that our paper does not want to present a full, complete interpretation of Nishida or Nishitani; on the contrary, we simply hope that it can represent a first step towards a new approach to these difficult thinkers. Such an approach is driven by two attempts. The first one is to push analytic philosophers to, at least, entertain the thought that it is not enough to blindly presuppose that the structure of reality is consistent. Indeed, important historical figures seem to deny it. The second attempt is to engage with the two philosophers discussed here for whom they really are interesting, provocative philosophers. And if, while we are reading them, we discover that the structure of reality might be inconsistent, well, let it be so.

Notes

We thank the referee and editor for drawing our attention to the methodological concern.

At the early stage of the development of his logic of place, he equates absolute nothingness with a specific kind of consciousness. In his (1926b), he says: “It can be said that consciousness that is conscious is the place of absolute nothingness” (Takeda et al. 2002, VII, p. 222, our translation) (Nishida, 1926a) and Nishida (1926c) equates consciousness in this sense with the transcendent predicate. For example, he says:)“what we call consciousness means the transcendent predicate, which is a predicate but never a subject, as described above.” (Takeda et al., 2002, p. 501, our translation) However, as Davis (2017) reports, “an enveloping sense of “nothingness” [= nothingness as a place within which every object is] is provisionally associated with a kind of transcendental subjectivity of consciousness or the heart-mind. Ultimately, however, Nishida comes to posit absolute nothingness as the “place” (basho) that embraces both subjective (noetic) and objective (noematic) dimensions of reality. Thus, he relegates not only the privation of being but also subjective nothingness, in the sense of the “field of consciousness,” to a type of “relative nothingness”” (Davis, 2017, Section 3.3).

Priest (2021) makes the same point.

We borrow the horizontal/vertical terminology from Krummel (2012).

Is absolute nothingness, not a foundational element? The answer depends on whether absolute nothingness is not only self-identical but also not self-identical. Let n be absolute nothingness. Then, that absolute nothingness is a foundational element that is formally written as \(\forall y (n \rightarrow y \supset n =y)\). n is the only instance that makes the antecedent of the conditional true, and, as we have seen, n makes the antecedent false as well: “\(n \rightarrow n\)” is both true and false. So let us consider \(n \rightarrow n \supset n = n\). Given that n is self-identical, its consequent is true only (t, for short) or both true and false (b, for short). Given the paraconsistent logic LP, since its antecedent is b, the whole conditional is t if its consequent is t, and it is b if its consequent is b as well. In the former case, “\(\forall y (n \rightarrow y \supset n =y)\)” is t; and the latter case, it is b.

For more detailed discussion on parafundationalism, see Casati (2022)

For a dialetheic interpretation of the late Nishida, see chapter 7 of Deguchi et al. (2021).

References

Bliss, R., & Priest, G. (2018). Metaphysical dependence and reality: East and West. In: Steven Emmanuel (Ed.), Buddhist philosophy: A comparative survey (pp. 63–86). Basil Blackwell.

Carter, R. (2013). The Kyoto School: An introduction, State University of New York Press.

Casati, F. (2018). ‘Heidegger’s Grund: (Para-)Foundationalism’ in Bliss Ricki and Graham Priest (eds.) (2018). Reality and its structure: Essays in fundamentality, Oxford University Press. pp. 291–313.

Casati, F. (2017). Being\(_{g}\): Gluon theory and inconsistent grounding. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 25, 536–44.

Casati, F. (2022). Heidegger and the contradiction of Being: an analytic interpretation of the late Heidegger. New York: Routledge.

Davis, B.W. (2017). The Kyoto School, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2017/entries/kyoto-school

Deguchi, Y. (2014). ‘Nishitani on Emptiness and Nothingness’ in Liu JeeLoo and Douglas Berger (eds.) Nothingness in Asian Philosophy, Routledge.

Deguchi, Y. (2015). ‘Constructing logic of emptiness: Nishitani, Jizang, and Paraconsistency’ in Tanaka Koji, Yasuo Deguchi, Jay Garfield and Graham Priest (eds.) The Moon Points Back, Oxford University Press.

Deguchi, Y., Garfiled, J., Priest, G., & Sharf, R. (2021). What can’t be said: Paradox and contradiction in East Asian thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Krummel, J. (2012). Basho, world, and dialectics: An introduction to the philosophy of Nishida Kitar ō. Place and Dialectic: Two Essays by Nishida Kitar ō, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3–34.

Nishida, K. (1926a). ‘Place’ (

), in Takeda et al. (2002-9), vol. III, pp. 415-77. English translation, Krummel, J.W.M. and Nagatomo, S., Place and Dialectic: Two Essays by Nishida Kitaro, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

), in Takeda et al. (2002-9), vol. III, pp. 415-77. English translation, Krummel, J.W.M. and Nagatomo, S., Place and Dialectic: Two Essays by Nishida Kitaro, Oxford: Oxford University Press.Nishida, K. (1926b). ‘The problem of consciousness left behind’ (

) in Takeda et al. (2002–9), vol. VII, pp. 215–224.

) in Takeda et al. (2002–9), vol. VII, pp. 215–224.Nishida, K. (1926c). ‘A reply to Dr. Souda’ (

) in Takata et al. (2002–9), vol. III, pp. 479–504

) in Takata et al. (2002–9), vol. III, pp. 479–504Nishida, K. (1930). The system of self-consciousness of the universal, (

) in Takeda et al. (2002–9), vol. IV.

) in Takeda et al. (2002–9), vol. IV.Nishitani, K. (1982). Religion and nothingness. University of California Press.

Nishitani, K. (1990). The self-overcoming of nihilism, State University of New York Press.

Parkes, G. (2014). Nishitani Keiji on practicing philosophy as a matter of life and death. In Davis Bret (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of Japanese philosophy. Oxford University Press.

Priest, G. (2014). One: Being an investigation into the unity of reality and of its parts, including the singular object which is nothingness. Oxford University Press.

Priest, G. (2017). Entangled gluons: Replies to Casati, Han, Kim, and Yagisawa. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 25, 560–67.

Priest, G. (2021). ‘Nothingness and the ground of reality: Heidegger and Nishida’, in Bernstein, S. and T. Goldschmidt, (Eds.). (2021). Non-Being: New Essays on the Metaphysics of Non-Existence (pp. 17–33). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Takeda, A., Riesenhueber, K., Kosaka, K., & Fujita, M. (Eds.). (2002). Nishida Kitaro Zenshu, New Edition, twenty four volumes. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at The 3rd Conference on Contemporary Philosophy in East Asia (August 19–20, 2016, Seoul National University). We thank Ricki Bliss and Yasuo Deguchi for their helpful discussion and comments on some of the earlier versions of the present paper. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JS16H03344, JS17F17004.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by The University of Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

We declare no conflict of interest associated with the present paper except the funding specified in the acknowledgments section and that one of the authors (Naoya Fujikawa) is an editorial board member of the Asian Journal of Philosophy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Casati, F., Fujikawa, N. Inconsistent metaphysical dependence: cases from the Kyoto School. AJPH 3, 23 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44204-024-00155-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44204-024-00155-w

), in Takeda et al. (2002-9), vol. III, pp. 415-77. English translation, Krummel, J.W.M. and Nagatomo, S., Place and Dialectic: Two Essays by Nishida Kitaro, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

), in Takeda et al. (2002-9), vol. III, pp. 415-77. English translation, Krummel, J.W.M. and Nagatomo, S., Place and Dialectic: Two Essays by Nishida Kitaro, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ) in Takeda et al. (2002–9), vol. VII, pp. 215–224.

) in Takeda et al. (2002–9), vol. VII, pp. 215–224. ) in Takata et al. (2002–9), vol. III, pp. 479–504

) in Takata et al. (2002–9), vol. III, pp. 479–504 ) in Takeda et al. (2002–9), vol. IV.

) in Takeda et al. (2002–9), vol. IV.