Abstract

The aim of this paper is to assess the relation between causation and the notion of emptiness described in Buddhist philosophy. While the Madhyamaka school argues that some entity’s being caused implies its being empty, some contemporary authors have argued that there is a ‘Humean’ regularity account of causation that can both be understood as a plausible model of the earlier Buddhist Abhidharma account of causation and also block the Madhyamaka inference from causation to emptiness. After describing the Abhidharma account of causation, the ‘Humean’ regularity account and the Madhyamaka argument from causation to emptiness, we assess some ways in which this argument may be developed, with particular focus on the ‘ladder of causation’ and on the Madhyamaka account of time. The debate about the relation between causation and emptiness, it appears, is a facet of a more comprehensive metaphysical debate between a (moderate) foundationalism and a thoroughgoing anti-foundationalism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For some discussion of the concept of svabhāva, see Westerhoff 2007.

Vasubhandu’s Abhidharmakośa 6:4, La Vallé Poussin and Pruden 1988–90: 3. 910–11. On the latter see also Walser 2005: 242: ‘[I]f, when one mentally removes a factor from a given concept, that concept is no longer possible, then the concept is not an ultimately existent dharma’.

Siderits 2022a: 53, note 7

Siderits 2021: 249

See Siderits 2014: 443.

The reason why Abhidharma defends mereological reductionism is based on considerations of identity and difference. Not unreasonably, the Ābhidharmika holds that entities we consider to be fully real should stand in determinate relations of identity and difference with one another. This, however, presents a difficulty if we consider a whole and its parts. The two cannot be identical, since a whole is one and the parts are many, and one entity cannot have two contradictory properties. If they are distinct, on the other hand, we should be able to find the whole independent of its part. Yet this is never the case; we do not encounter a bicycle at a location separate from its parts. If instead whole and part are distinct and spatially coincide, the whole is spread out in space and so contains parts, which are distinct from the parts of the bicycle they spatially coincide with. In addition to this curious duplication, we might then wonder whether there is also a second-order whole consisting of all the parts of the whole (parts which are distinct from the bicycle parts), which spatially coincide with the whole, and so on, all the way up an infinite regress.

The way to solve this problem, the Ābhidharmika argues, is to give up the assumption that wholes and parts stand in determinate relations of identity and difference. They do not do so because wholes are not fully real, but merely conceptual-linguistic projections onto a set of objects that are fully real, namely the parts.

It seems to be difficult to make sense of the notion of a functional unity that is a whole in a purely mind-independent way, without referring in some way to human interests and concerns.

This distinguishes the Sautrāntika Abhidharma’s view of time from that of the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma, which holds something more akin to a block-universe theory of time, arguing that the past, present, and future all exist. See Westerhoff 2018: 60–66.

Siderits 2016: 113

Siderits 2016: 113

Siderits 2014: 442–443

Siderits 2014: 442

Siderits 2014: 447

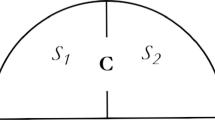

The picture of the succession of boards would correspond the view of the Sautrāntika Abhidharma, which is our present focus, according to which on only the present board is ever real. The idea of the three-dimensional block of boards would correspond to the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma’s theory according to which the past, present, and future all exist.

For a view of the Humean mosaic where the supervenience base does not consist of ‘pointlike particulars characterised by intrinsic categorial properties and standing in external relations’ but of ‘momentary sense data characterised by intrinsic categorical properties and standing in external relations’, see Kodaj 2021.

More accurately, we should speak of cell types at a specific time being correlated with cell types at other times with specific probabilities. However, we can ignore this complication for present purposes.

Bliss 2015: 93

‘What is it, then, about some sets of event pairs, but not others, that make them dependently related, if not some causal link present in some cases but not in others? Nāgārjuna replies (1: 5) that it is the regularities that count. Flickings give rise to illuminations’. Garfield 1994: 224.

Garfield 1994: 223

For further discussion of ‘Hume’s dictum’ to this effect, see Bliss 2015: 80.

Garfield 2015: 26: ‘Hume regards events as ‘independent existences’, for Buddhists, dependent origination guarantees that nothing is an independent existent’.

Let us stress once more we are not concerned with the question whether Hume himself would have endorsed this view.

Garfield 1994: 234. Incidentally, this point implies that even if we accept the existence of ‘real patterns’ in the world, we could not equate them description-independent causal regularities.

For further discussion of this, see Westerhoff 2009: 94–99.

See for example the ‘projectivist’ interpretation discussed by Bliss 2015: 78.

The argument obviously will not cover entities taken to be uncaused (such as space or nirvāṇa in the case of the Abhidharma) or abstract objects (in the case of contemporary philosophy). While Madhyamaka has something to say about these kinds of things as well, we will ignore them for present purposes.

Adapted from Bernstein 2017: 218. Ābhidharmikas are ‘mereological idealists’, that is, they hold that some parts are part of a whole if and only if at least one observer mentally superimposes a mereological composition on the parts. They do not accept the existence of an objectively real mereological composition operations such that some group of objects forms a whole whether or not anyone has ever conceived of them as a whole. The mereological argument for emptiness would not go through if they were objectivists about parthood. If some entities formed a whole no matter what the Ābhidharmika could not say that only the parts, but not the whole exists.

For a more detailed presentation of this argument, see Siderits 2004: 407–408, 411–413.

See Siderits 2004: 411–413

For a concise account of the debate between these two schools concerning the simultaneity of causation and presentism, see Westerhoff 2018: 60–70.

Siderits locates the charge of question-begging at a different point, namely connected with ‘Principle P’ (‘If a relational tie is conceptually constructed, then any property of one of its relata that involves essential reference to that tie must likewise be conceptually constructed’ (Siderits 2004: 411)), which allows us to move from the claim that causation is conceptually constructed to the claim that any caused entity is likewise constructed and hence empty, instead of applying it to the Madhyamaka claim that the causal relation is conceptually constructed: ‘As for the Principle P that I invoked in order to turn an argument for the emptiness of causation into an argument for the emptiness of anything that is caused, I now think it would be rejected by the causal realist opponent as involving a question-begging essentialism’ (Siderits 2016: 114). Yet the Ābhidharmika would presumably not have a problem appealing to Principle P when the ‘relational tie’ is the ‘part of’ relation, in order to argue that any entity that involves essential reference to parthood is conceptually constructed. The worry seems to be that on the basis of the assumptions the Mādhyamika has introduced in his argument for Causal Idealism the Ābhidharmika sees no reason to see the causal ‘relational tie’ as conceptually constructed in the first place.

Siderits 2014: 448: ‘I am thus not certain that a successful Madhyamaka argument against the ‘Humean’ option is to be found in the Madhyamaka literature’.

Also referred to as the ‘ladder of causation’; see Pearl/Mackenzie 2018, ch. 1.

Gold 2015: 112 ascribes an interventionist understanding of causation to Vasubandhu.

Bareinboim et al., 2022: 528-529

Barenboim et al., 2022: 533

See Cartwright 1989: 39: ‘‘How can we infer causes from theory?’ […] [W]e can do so only when we have a rich background of causal knowledge to begin with. There is no going from pure theory to causes, no matter how powerful the theory’.

Siderits 2022b: ‘[P]erhaps it is a mistake to think of causation as any more than just invariable succession of one sort of event by an event of another sort. If that is the right way to think about causation, then the fact that we cannot explain why a given sort of dharma always arises after the occurrence of a certain aggregate of events and conditions should not distress us. It might just be that this is the way that the world happens to work, and nothing more needs to be said about the matter’.

‘Since our ordinary idea of causation involves the further component of necessary connection, one can say, with Hume and Nāgārjuna, that that idea involves conceptual construction. But this does not show that causal relations could not obtain between ultimately real entities’ (Siderits 2016: 113-114).

We might conceive of space and time as sets of particularised properties as well, so that the ‘concomitance’ of two particularised properties, for example, would be accounted for as the co-occurrence of the two properties and a specific temporal property in a bundle. This would leave as with a picture according to which reality ultimately consisted of bundles of property particulars, bundles which have no spatial or temporal location in themselves. Rather, space and time, as well as all the other properties of the phenomenal world, would emerge from this abstract list of property bundles. Apart from the fact that it is far from clear how to spell this out in detail, it is evident that we would no longer be dealing with a Humean conception of causation, but rather with an ontology according to which there are no spatial, temporal, or causal relations at the most fundamental level of reality.

‘No Buddhist school accepts the notion of time as an independent eternal receptacle within which temporal phenomena unfold in a natural sequence’ (Compendium Compilation Committee 2017: 241).

A detailed account of the Madhyamaka theory of time is unfortunately still lacking in contemporary literature. Interested readers might begin by consulting chapter 19 of Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā and chapter 11 of Āryadeva’s Catuḥśataka.

The thoroughgoing constructivism we find in Madhyamaka leads to problems when added to an objective understanding of time. If time exists over and above human conceptual activity, the past (the ‘ancestral world’) will exist in a similar manner, locating a large part of reality outside of the realm of the constructed. See James 2018 and Bitbol 2019 for further discussion.

Siderits/Katsura 2013: 207–211

As Candrakīrti points out in his Prasannapadā, commenting on Mūlamadhyamakakārikā 19:1: ‘one thing cannot depend on another thing which does not exist, as in the case of the son of a barren woman, a garland in the sky and the flowers it contains, or sand and sesame oil’ (yasmāt yasya hi yatra asattvam tat tena nāpekṣyate| tadyathā vandhyā srī svatanayena gaganamālatīlatā svakusumena sikatā svatailena, Poussin 1913: 382: 13–15).

Tsong kha pa stresses another aspect of this point, the dependence of the past and the future on the present when commenting on Mūlamadhyamakakārikā 19:1: ‘[T]he past has to be posited as that which is past with respect to the present, and the future is that which has not yet come in the present’ (Ngawang Samten/Garfield 2006: 395), da ltar ba las ‘das pas ‘das pa dang der ma ‘ongs pas ma ‘ongs par ‘jog dgos (Tsong kha pa 1992: 337).

Mūlamadhyamakakārikā 19:5, (Siderits/Katsura 2013: 210–211)

Mūlamadhyamakakārikā 19:6, (Siderits/Katsura 2013: 211)

Mūlamadhyamakakārikā 11:1, (Siderits/Katsura 2013: 123–124)

Mūlamadhyamakakārikā 11:2, (Siderits/Katsura 2013: 123–124)

‘The conceptual and material properties of an object require consciousness in order to be experienced. In turn, consciousness depends on name-and-form [that is, matter and mental functions other than consciousness] as that which provides the content of what consciousness is aware of. This reciprocal conditioning of consciousness and name-and-form presents a basic matrix of experience, a continuous interplay between consciousness on the one hand and name-and-form on the other that, according to the early Buddhist analysis, builds up the world of experience’ (Anālayo 2018: 11).

For the Mādhyamika, to use the terminology introduced in Section 1, the absence of intrinsic existence excludes the existence of any entities with intrinsic nature.

References

Anālayo, B. (2018). Rebirth in early Buddhism & current research. Wisdom Publications.

Bareinboim, E., Correa, J. D., Ibeling, D., & Icard, T. F. (2022). On Pearl’s hierarchy and the foundations of causal inference. In Hector Geffner, Rina Dechter, Joseph Y. Halpern: Probabilistic and Causal Inference: The Works of Judea Pearl, Association for Computing Machinery (pp. 507–556). New York.

Bernstein, S. (2017). Causal idealism. In Tyron Goldschmidt, Kenneth L. Pearce: Idealism. New Essays in Metaphysics (pp. 217-230). Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bitbol, M. (2019) Maintenant la finitude. Peut-on penser l’absolu? Flammarion, Paris.

Bliss, R. (2015). On being Humean about the emptiness of causation. In K. Tanaka, Y. Deguchi, J. L. Garfield, & G. Priest (Eds.), The Moon Points Back (pp. 67–96). Oxford University Press.

Cartwright, N. (1989). Nature’s capacities and their measurement. Clarendon Press.

Chakrabarti, A. (2019). Realisms interlinked. Object, subject, and other subjects. Bloomsbury Academic, London.

Compendium Compilation Committee. (2017). Science and philosophy in the Indian Buddhist classics. Volume 1: The Physical World, Wisdom Publications, Boston.

Dennett, D. (1991). Real patterns. Journal of Philosophy, 88, 27–51.

Ganeri, J. (2001). Philosophy in classical India. The proper work of reason. Routledge, London, New York.

Garfield, J. (1994). Dependent arising and the emptiness of emptiness: Why did Nāgārjuna start with causation? Philosophy East and West, 44(2), 219–250.

Garfield, J. (2001). “Nāgārjuna’s theory of causality: implications sacred and profane. Philosophy East and West, 51(4), 507–524.

Garfield, J. (2015). Engaging Buddhism. Oxford University Press, New York.

Garfield, J. (2019). The concealed influence of custom. Oxford University Press, New York.

Gold, J. (2015). Paving the great way. Columbia University Press, New York.

Goodman, C. (2004). The treasury of metaphysics and the physical world. Philosophical Quarterly, 54(216), 389–401.

James, S. (2018). Madhyamaka, metaphysical realism, and the possibility of an ancestral world. Philosophy East and West, 68(4), 1116–1133.

Ladyman, J., & Ross, D. (2007). Every thing must go: Metaphysics naturalized. Oxford University Press.

de la Vallée Poussin, L. (1913). Mūlamadhyamakakārikās (Mādhyamikasūtras) de Nāgārjuna: avec la Prasannapadā commentaire de Candrakīrti, Académie imperiale des sciences, St Petersburg.

de la Vallée Poussin, L. (1988-1990). Abhidharmakośabhāṣyam of Vasubandhu. English translation by Leo M. Pruden, Asian Humanities Press, Berkeley.

Lewis, D. (1986). Philosophical papers II. Oxford University Press.

Ngawang Samten, G, & Garfield, J. (2006). Ocean of reasoning. Oxford University Press, New York.

Pearl, J., & Mackenzie, D. (2018). The Book of Why. Basic Books.

Siderits, M. (2004). Causation and emptiness in early Madhyamaka. Journal of Indian Philosophy, 32(4), 393–419.

Siderits, M. (2014). Causation, ‘Humean’ causation, and emptiness. Journal of Indian Philosophy, 42, 433–449.

Siderits, M. (2016). Studies in Buddhist philosophy. Oxford University Press.

Siderits, M. (2021). Buddhism as philosophy, 2nd edition. Hackett, Indianapolis, Cambridge.

Siderits, M. (2022a). How things are. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Siderits, M. (2022b). “Nāgārjuna.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.763

Siderits, M., & Katsura, S.(2013). Nāgārjuna’s middle way: The Mūlamadhyamakākarikā. Wisdom.

Tsong kha pa. (1992). dBu ma rtsa ba’i tshig le’u byas pa shes rab ces bya ba’i rnam bshad rigs pa’i rgya mtsho, wA Na mtho slob dge ldan spyi las khang, Sarnath, Varanasi.

Weatherson, B. (2015). Humean supervenience. In B. Loewer & J. Schaffer (Eds.), A Companion to David Lewis (pp. 101–115). John Wiley & Sons.

Westerhoff, J. (2007). The Madhyamaka concept of svabhāva: ontological and cognitive aspects. Asian Philosophy, 17(1), 17–45.

Westerhoff, J. (2009). Nāgārjuna's Madhyamaka. A Philosophical Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Westerhoff, J. (2018). The golden age of Indian Buddhist philosophy. Oxford University Press.

Westerhoff, J. (2020). The non-existence of the real world. Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Westerhoff, J. Does causation entail emptiness? On a point of dispute between Abhidharma and Madhyamaka. AJPH 2, 69 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44204-023-00121-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44204-023-00121-y