Abstract

Research on climate anxiety is rapidly growing, with ongoing exploration of population prevalence, contributing factors, and mitigation strategies that transform anxiety into helpful action. What remains unclear is whether and how to delineate climate anxiety from mental ill health. A limited conceptualization of climate anxiety restricts efforts to identify and support those adversely affected. This paper draws on psychological and existential theories to propose a theoretical model of climate anxiety and coping, extending previous conceptualizations. The model theorizes that climate change evokes an existential conflict that manifests affectively as climate anxiety (and other emotional experiences), wherein cognitive and behavioral coping processes are activated. These processes fall on a continuum of adaptivity, depending on functional impact. Responses might range from meaningful engagement with activities that address climate change to maladaptive strategies that negatively impact personal, social, and occupational functioning. Applications of this model in research and practice are proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Climate change has negative implications for population mental health and well-being [1]. Direct exposure to extreme weather events is associated with trauma-related disorders, as well as elevated anxiety, depression, substance use, grief, and suicidal ideation [2, 3]. In addition, temperature fluctuation is associated with anger, stress, increased fatigue, major depressive disorder, self-harm, and suicide attempts [3, 4]. Climate change may also indirectly cause significant social, economic, and environmental risk factors for mental illness, including forced migration, food scarcity, and conflict between and within nations [2, 5,6,7]. Irrespective of degree of exposure to such stressors, psychological and emotional responses to anthropogenic climate change are well documented [7, 8]. Simple awareness of the climate crisis can evoke ‘climate anxiety’ [6].

The definition of climate anxiety varies across different fields of research; however, it is commonly understood as a fear of environmental change and its impacts [9], as well as a cognizance that the ecological foundations of the planet are in the process of collapse [9]. Reports of those with lived experience of climate anxiety has brought attention to this phenomenon in the media, across research and in healthcare [10, 11]. Despite growing efforts to expand scientific knowledge on climate anxiety, a conceptual psychological understanding of how one copes is yet to be developed [12, 13]. This restricts the ability to accurately identify and provide meaningful support to those affected [12, 14]. This review aims to:

-

i.

Provide an overview of the historical background, theories and measures of climate anxiety, with consideration of broader theoretical perspectives on anxiety and coping,

-

ii.

Respond to recommendations made by systematic reviews to refine the definition of climate anxiety and clarify its adaptivity or helpfulness,

-

iii.

Propose an integrated theoretical model to conceptualize the experience of climate anxiety and how people may cope with these feelings; and,

-

iv.

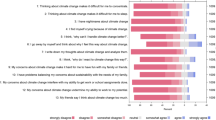

Draw on the model to discuss considerations and approaches that may be relevant for researchers and practitioners working with or exploring climate anxiety (see Fig. 1 for a summary).

1.1 A history of research on climate anxiety

1.1.1 Eco-anxiety

While climate anxiety is a subject that has grown in interest more recently, research investigating attitudes towards global environmental issues (e.g., ozone depletion, global warming) dates back to the 1980’s. Between 1982 and 1986, 12 European studies showed that on average, 34–38% of the public were concerned or worried about changes to the climate as a result of carbon dioxide emissions [15]. In a 1994 global survey of environmental attitudes, the proportion of those viewing global warming as a “serious threat” varied by country, from 20–40% in countries such as Nigeria, India, and the United States to more than 70% in Brazil, Germany and Portugal [16].

Research on mental health and the environment proliferated from the 1990’s to the early 2000’s, with evidence suggesting that contact with the natural world is beneficial to well-being and can enhance feelings of relaxation, peacefulness and tranquility [17]. The term ‘Eco-anxiety’ subsequently emerged in print media feature articles, predominantly in political discourse or in interviews with ‘eco-psychologists’. Initially, there was a focus on nature-based therapeutic treatment approaches (e.g., wilderness therapy, green exercise) to support individuals reporting distress regarding environmental issues and disconnection from nature [18,19,20,21]. With increasing reports of distress over climate change in the news and in healthcare, research turned its attention to climate change and mental health symptoms, reporting associations between concern or distress about climate change with anxiety, stress, and impairments to daily living (e.g., interfering with work, school or relationships) [22,23,24]. The term eco-anxiety was soon adopted into the literature and has been characterized as a “chronic fear of environmental doom” [25, 26].

1.1.2 Climate anxiety and its impacts on wellbeing

In recent years, the introduction of the term ‘climate anxiety’ has provided increased specificity in terminology. While climate anxiety continues to be used interchangeably with eco-anxiety in the literature, eco-anxiety is more broadly understood as encompassing emotional distress towards environmental issues and is not specific to climate change [9]. In contrast, climate anxiety may involve anxiety, dread, and despair specifically in response to climate change-related issues, including loss of natural places, ecological collapse and anticipated future harm due to climate change-related stressors (e.g., extreme weather disasters, forced migration). Awareness of climate change is sufficient to elicit climate anxiety [21, 24, 27], where worries may be about the implications for oneself, others, future generations, animals, the environment, or the future state of the world [28]. Awareness may occur through direct exposure (e.g., experiencing extreme weather-related events or gradual environmental changes over time) as well as indirect exposure (e.g., news, media or education around climate change-related issues) [29]. Empirical research on eco anxiety and climate anxiety continues to grow rapidly, and several systematic reviews have been conducted on the topic (see Table 1 for a summary). Collectively, these reviews highlight the need to strengthen the conceptualization of climate anxiety and to explore avenues of support for those who are affected by it [12, 13, 30,31,32]. In responding to these recommendations, the adaptivity (i.e., helpfulness) of climate anxiety must be clarified, which we attempt to address within this paper.

A growing consensus is that for some, climate anxiety can become maladaptive and interfere with functioning [24, 33,34,35,36]. Based on experiences with clients in clinical practice, Hickman [10] proposes different levels of severity from mild (some distress that responds to distraction, reassurance, and individual action, e.g., altering diet and recycling used materials) to severe (changes in cognition such as intrusive thinking, terror, no trust in solutions or experts, and an inability to regulate emotional responses). This severe level of climate anxiety appears to overlap in some respects with clinical anxiety disorders, particularly in relation to a significant level of distress leading to impairments in personal, social, and occupational functioning [37, 38]. For some, climate anxiety may even exacerbate pre-existing mental health problems such as generalized anxiety [39]. However, fundamental to clinical anxiety disorders is that the response is often out of proportion to the threat or a maladaptive response to uncertainty, whereas climate change carries complex, real and devastating impacts on human life.

1.1.3 Considering the function of climate anxiety

Given the negative implications of climate change, climate anxiety could serve a constructive purpose. Emotions are psychological states accompanied by cognitive processes, behavioral responses, and patterns of neurophysiological changes [40, 41]. According to Basic Emotion Theory, emotions enable one to respond to threats and opportunities in the environment [42]. Anxiety particularly functions as a warning sign when survival or well-being is threatened, triggering adaptive responses to eliminate the threat [43]. Autonomic, neurobiological, cognitive, and behavioral patterns may be activated as a means of escaping or managing the danger (e.g., fight, flight, freeze responses) [24, 34]. Common catalysts for anxiety are situations i) that are open to different interpretations (ambiguous situations), ii) in which there is no prior experience to draw from (novel situations) or iii) where it is unclear what may transpire (unpredictable situations). These conditions, which lead to high uncertainty and a level of uncontrollability, may exacerbate perceptions of threat [44, 45]. In turn, anxiety and the accompanying cognitive and behavioral processes are enacted to try to manage the ongoing threat and the underlying uncertainty, when unable to eliminate the threat completely [45].

Climate anxiety could therefore be, to an extent, necessary to motivate the transition to a sustainable future. As such, it is important to avoid the use of terminology that unhelpfully pathologizes the experience. It is also worth noting that many individuals may respond to feelings of climate anxiety in ways that are constructive (e.g., activism, research, helping others) [29, 46], with some studies showing associations between climate anxiety and pro-environmental behavior, environmental activism and increased engagement with politics [47, 48]. Emerging evidence also suggests that climate anxiety can potentially lead to a gain in functioning (such as being more motivated or more socially connected) when accompanied by more balanced (i.e., more hopeful or positive) re-appraisal styles of thinking [49]. Climate anxiety may therefore be the alarm bell signaled when one appraises climate change as catastrophic and uncertain. This response prompts an individual to act in order to reduce or manage the threat of climate change. It can thus be argued that it is how someone copes with climate change and anxiety, rather than the emotion itself, that varies in adaptivity.

1.1.4 Considering coping with anxiety and other emotions

Coping is a cognitive and behavioral process activated to manage, tolerate, or reduce adversity or stress [50, 51]. Several styles of coping are evidenced in the climate change literature, especially in work with young people [52,53,54]. Firstly, emotion-focused coping involves attempts to soothe, regulate, or remove emotions engendered by the climate crisis. Problem-focused coping relates to thinking about, talking about, and acting on climate mitigation. Meaning-focused coping involves a positive or more balanced re-appraisal of climate change through hope and trust. Distancing refers to the strategies one uses to move away from or distract oneself from climate change or their negative emotions toward it. Lastly, de-emphasizing the seriousness of climate change can range from apathy to skepticism, and even denial. Pihkala [55] synthesizes some of these ideas using a process model, which posits that eco anxiety and ecological grief activate a process of coping. Three dimensions of coping are described: action, grieving (and the processing of other emotions) and distancing. As individuals traverse these coping tasks over time, it is theorized that they may then enter a phase of living with the climate crisis. During this phase, coping becomes focused on action, emotional engagement (including grieving), and self-care (which can include distancing). Pihkala [55] suggests that difficulties in adjustment or coping could lead to anxiety, depression, and problematic avoidance. Indeed, we argue that coping strategies can become adaptive or maladaptive depending on the effect to one’s well-being and functioning.

While attempting to cope with climate anxiety, other emotional responses may understandably arise, which may require further use of coping resources. For example, learning about ineffectual government responses or how corporations contribute to emissions, may provoke anger, frustration, and feelings of betrayal [33]. Alternatively, ecological grief may be felt in response to physical ecological losses (e.g., species, environmental landscapes), loss of environmental and cultural knowledge, sense of place and home, and to security, stability, and even life [34, 56]. This grief can become disenfranchised (prolonged and exacerbated) when invalidated by others through dismissal or minimization [26, 27, 29]. Failure to prevent these ecological losses due to collective inaction may prompt feelings of hopelessness or helplessness [39]. On the other hand, connecting with nature, others, or one’s values within the context of climate change, could lead to hope, connection, optimism, gratitude, or soliphilia (a feeling of love and sense of responsibility to protect the planet) [52, 57,58,59]. These emotional states could overlap and intersect with climate anxiety, influencing the way one cognitively and/or behaviorally responds [60]. Evidence suggests anxiety combined with anger or hope, for example, may prompt pro-environmental behavior [35, 60]. While it can be hypothesized that climate anxiety is an initial emotional response typically evoked by the threats of climate change, it is important to acknowledge that emotions are sensitive to situational factors such as context, cultural norms, personality, and cognitive attributions [41, 60,61,62]. Therefore, as the context of the climate crisis continues to change, emotional states including climate anxiety may oscillate in salience, valence (pleasant to unpleasant), arousal (passive to activated), duration and intensity or severity [10]. This too will have flow-on effects for coping. Other emotional responses to climate change, which are difficult to disentangle from climate anxiety, should therefore be incorporated in measurement and research.

1.2 Considering existing measures of climate anxiety

Existing measures of climate anxiety provide compelling evidence of climate anxiety as a multi-dimensional construct. In particular, Clayton and Karazsia [24] developed the Climate Change Anxiety Scale, identifying two unique dimensions: cognitive-emotional impairment and functional impairment [24, 63, 64]. Hogg and others [65] also developed and validated a scale and identified four underlying constructs of climate anxiety: affective symptoms, rumination, behavioral symptoms and anxiety regarding one’s negative impact on the planet. Although both scales helpfully point to the presence of affective, cognitive, and behavioral experiences, each has some conceptual limitations. Firstly, there is a tendency in both scales to focus on impairment. While capturing the presence of potentially unhelpful responses, the scales do not capture the range and presence of adaptive responses. By overlooking the potential for an individual to respond or cope constructively, research and intervention efforts are somewhat limited. Furthermore, individuals who experience climate anxiety whose coping may fall on the adaptive end of the continuum may require different types of support, which could be detected if measures focus primarily on coping.

Another limitation to existing measures is that they reduce the cognitive dimension of climate anxiety to excessive preoccupation with climate change or one’s own distress. This potentially overemphasizes repetitive thinking /excessive worry and limits the role that specific cognitive appraisals may have in developing and maintaining climate anxiety. While some climate anxious individuals may excessively worry, others may de-emphasize the seriousness of the threats, filter scientific versus catastrophic information, or reappraise the climate crisis by drawing on hope and trust in mitigation efforts [18, 66]. These cognitive patterns may in turn influence both emotions (e.g., anxiety, dread, fear) and associated behaviors (e.g., pro-environmental behavior, avoidance).

Despite limitations, existing measures of climate anxiety are a useful platform for which to develop and extend the forthcoming theoretical conceptualization. Based on the current state of the literature, we argue that climate anxiety is best considered as an expected and understandable emotional response that encompasses emotions (e.g., fear, anxiety, dread) and physiological symptoms typical of anxiety (e.g., feeling tense). Yet how an individual processes or copes with these emotions (cognitively or behaviorally) likely falls on a continuum of adaptivity depending on functional impact of the coping response [67]. When coping becomes highly maladaptive, this may be attributable to pre-existing or underlying symptoms of a diagnosable mental health disorder.

This conceptualization aligns with both suggestions that climate anxiety emotions should not be considered a mental health disorder, but also that coping can become clinically maladaptive and lead to functional impairment. Individuals should be supported to express their experiences of climate anxiety, which may help them to develop more helpful and adaptive coping strategies [18, 46]. To further illustrate and expand on this conceptualization, broader psychological theories of anxiety will be drawn on to propose a theoretical model of climate anxiety and coping.

1.3 Considering broader theoretical perspectives

1.3.1 Cognitive psychology

Of the many cognitive theories that explain why or how an individual experiences anxiety, two will be applied to climate anxiety. Beck and Clark’s [68] information processing model proposes that the experience of anxiety is characterized by (1) an automatic detection of a threat (rapid, memory-based), (2) primal threat mode activation (e.g., escape/avoidance behavior or physiological arousal), and (3) conscious appraisal and reflective thinking (emotionally and/or logically reasoned) used to determine the best course of action to eliminate the threat [29, 68]. Further, this conscious appraisal comprises thought content (what the individual thinks) and thought process (the way the individual thinks). Applied to climate anxiety, an individual’s thoughts (content and process) may arise as a way to make sense of climate change and their feelings towards it, with the function of determining an appropriate course of action. For example, there is evidence that hopeful efficacy beliefs [69], meaning-focused thoughts and problem-focused thinking [70], are associated with environmental action and engagement. This, however, may not always be adaptive. Beck and Clark [68] suggest that dominance of the primal threat mode can lead to thinking that is unconstructive, excessive, or pathological. An individual experiencing climate anxiety may have less capacity for constructive thought when consistently under threat by adversity in life as well as climate-induced stressors (e.g., migration). For some, these thought processes may become unhelpfully habitual [71]. Furthermore, knowledge and experience stored in the long-term memory can influence how information is processed [72]. Adverse experiences can stimulate negative biases, which can lead to thinking biases and disordered cognition [73]. Experiencing a severe season of bushfires, for example, may lead to cognitive styles characterized by catastrophizing (e.g., “humanity is doomed”) or excessive preoccupation with past or anticipated losses. Conversely, beliefs and experiences held in long-term memory could motivate constructive thinking. One study, for example, found associations between habitual worrying about climate change (repetitive, automatic thinking) and pro-ecological worldviews, pro-environmental values, a ‘green’ identity, and pro-environmental behavior, suggesting a more constructive cognitive style [71].

A person’s beliefs about their own thoughts may also impact and maintain their anxiety [74]. According to metacognitive theory, one’s awareness, knowledge and perception of their thoughts can guide which coping strategies they select [74]. For example, an individual who believes they struggle to control their thoughts about climate change may unsuccessfully try to suppress their emotions or thoughts, leading to greater anxiety. For further consideration is whether the experience of climate anxiety is in general a direct and proportionate response to climate change related threats (e.g., ‘state anxiety’), or an extension of an individual’s tendency to experience anxiety or worry-based thinking styles (e.g., ‘trait anxiety’) [75, 76]. While some research has found that climate anxiety is associated with generalized anxiety and trait pathological worry [71], another study found that approximately 60% of participants scoring highly on state climate anxiety were absent in high trait anxiety [76]. While further research is needed to explore the role of cognitive styles and processes in managing and processing climate anxiety (e.g., metacognitive beliefs, knowledge, tendency to use specific thinking styles), existing literature points to a range of adaptive to maladaptive cognitive responses [29]. It is important to note that while unhelpful cognitions may play a role in climate anxiety, concerns about climate change reflect a natural response to an existential threat. There is an emerging body of work that seeks to understand the existential nature of climate anxiety.

1.3.2 The existential perspective

Existentialists regard humans as reflective and meaning-making beings, who are expected to naturally confront and reconcile shared existential concerns considered core to human life [77]. Awareness of existential concerns can elicit apprehension, angst, anxiety, grief, and dread [11, 78], threatening the core self and tasking one to make the change necessary to move forward in life with greater meaning and authenticity [11]. Death, meaning, guilt and isolation are among the common existential concerns that arise during the lifetime [77,78,79,80].

While limited empirical evidence has linked climate anxiety with existential concerns, several authors propose that climate change raises the salience of existential concerns such as mortality, thereby evoking climate anxiety [11, 29, 79]. One study conducted a thematic analysis to ascertain whether existential themes were present in interviews with psychotherapy patients describing their experiences of climate anxiety [11]. Within these interviews, patients described the salience of mortality, fearing the “death of humanity,” and the meaninglessness of existence, among other existential themes. It has also been suggested that feelings of vulnerability that arise when confronted with existential concerns may prompt the use of defense strategies (e.g., denial and apathy) as a means of restoring psychological equilibrium [68]. The proposed theoretical model thus considers climate anxiety as a manifestation of the existential conflict evoked by climate change, whereby one’s accompanying cognitive and behavioral strategies attempt to mitigate this conflict.

1.3.3 Systemic influences

How climate anxiety is experienced and coped with can be influenced by a range of factors outside of an individual’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral characteristics. There is accumulating evidence that suggests specific populations are at greater risk of climate anxiety. Research has linked an increased risk of climate anxiety or climate change-related distress to females [12, 23, 71, 81], young people [24, 33, 82], and individuals with pro-environmental identity [23, 71], left-leaning political values [83], and those with pre-existing anxiety or stress [9, 35, 76]. First responders, health care providers, activists, and scientists, who are more exposed to or have greater knowledge of the direct impacts of climate change, may be more likely to experience higher levels of climate anxiety [18, 29, 84]. Unique vulnerability to specific climate-related events may also foster heightened anxiety. For example, an individual may experience greater climate anxiety if damage brought by natural disasters (e.g., flooding, fires) presents a risk to their homes, livelihoods, and environment, particularly for those with strong cultural or spiritual connections to land [12, 85]. This may be especially the case for populations residing in the Global South, where climate change exacerbates pre-existing vulnerabilities such as extreme weather, scarcity of resources, forced migration, and poverty [86]. What is clear is that as climate change stressors (e.g., extreme weather events) fluctuate in salience for different groups across time, psychological and emotional responses are likely to be similarly dynamic [87].

Psychological responses to climate change should not be viewed in isolation, but rather as existing within layers of social, community, cultural, and political systems [86, 88, 89]. This has been conceptualized within a social-ecological framework, which illustrates how various nested contextual ‘systems’ within which an individual is embedded (e.g., family, peers, work or school, community, culture, the government) may shape whether and how that person experiences climate anxiety [86]. At the individual level, potential influences include temperament, biology/neurology, coping styles, any pre-existing mental health conditions, knowledge about climate change, as well as unique experience and vulnerability to climate change in their immediate context. At the microsystemic level, influences include the attitudes and experiences of family and friends, as well as how climate change is discussed or communicated in close relationships. Factors in the mesosystem may include community resources, community responses to climate change, as well as shared communal stress resulting from these changes. Exosystemic factors include governmental attitudes, collaboration or conflict between nations, the selection and implementation (or lack) of policies aimed to mitigate climate change, as well as how climate change is communicated in media. Additionally, overarching cultural influences in the macrosystem include cultural knowledge and attitudes, spiritual or religious connections to land, and potential loss of culture or cultural places due to climate change. While the conceptual model proposed in the current paper highlights affective, cognitive, behavioral, and existential dimensions of climate anxiety and coping at the individual level, it is important for researchers and practitioners to consider how these domains interact with an individual’s wider social-ecological contexts (for further detail, refer to Crandon, Scott [86]).

1.4 Model development

In the current paper, the authors constructed a model of climate anxiety and coping by drawing together the theoretical concepts previously described using a ‘top-down’ approach. Based on social-ecological theory and its application to climate change (see Crandon et al. [86]), environmental factors were considered as shaping all climate-related triggers and therefore how someone responds to those triggers. For this reason, systemic and contextual factors are depicted at the top of the model. From here, the model shows that acute and chronic triggers can then evoke climate anxiety. Existential theories were considered and ultimately included in the model to highlight that climate anxiety is an existential conflict that can be minimized or strengthened depending on the subsequent process of coping. The existential conflict (i.e., climate anxiety) then establishes an affective experience which has emotional and physiological components. The authors then applied the literature on coping to illustrate how climate anxiety can prompt a process of coping, which encompasses ongoing cognitive and behavioral efforts/strategies to reduce or mitigate the existential conflict of climate change and its associated experienced affect. Well-established evidence-based cognitive and behavioral theories were acknowledged in the model by showing how affect, cognitive appraisals and behavioral responses are bidirectionally influenced, and impact on overall functioning. Finally, the ongoing coping process informs the degree of adaptivity to the existential conflict caused by climate change.

2 Introduction of a theoretical model of climate anxiety and coping

The current conceptual model proposes that even after acknowledging systemic influences [86], climate anxiety is an existential conflict that leads to affective/emotional experiences. Individuals manage and respond to these experiences using cognitive and behavioral coping processes (see Fig. 2), which can be adaptive (when reinforcing functioning) or maladaptive (when interfering with functioning). Cognitive and behavioral coping may separately or simultaneously focus on solving or mitigating the problems of climate change, as well as soothing or removing the emotions evoked by it. We propose that individuals are not fixed to one process but can engage in more than one at the same time and over time, thereby oscillating on a continuum between low and high degrees of adaptive coping. Importantly, the affective (felt emotion/s), cognitive (thought content and process), and behavioral responses (actions and impacts) will be unique for an individual, as influenced by intrapersonal psychological factors, as well as the external social-ecological systems surrounding them.

2.1 Adaptive coping

When faced with triggers of the climate crisis, processing of climate change as a significant, overwhelming challenge may lead to existential conflict. As part of this conflict, autonomic arousal (e.g., discomfort, unease, shakiness, impaired concentration, increased heart rate, muscular tension, tight chest) and emotional experiences (e.g., angst, anxiety, fear, dread, anger, helplessness) act as a cue, whereby cognitive appraisal determines a course of action to reduce the threat [90]. This appraisal involves specific thoughts (e.g., what an individual thinks about climate change) and thought process (e.g., the mechanics of thinking). Adaptive thought content may be meaning-focused or hope inducing, be influenced by strongly held beliefs or values, involve interpretations about the greater historical context of climate change, or considerations of different climate solutions being developed and implemented [66]. For adaptive thought processes, an individual may engage in problem solving/solutions-focused thinking or cultivate acceptance of uncertainty and negative emotions [49].

These adaptive cognitive modes interact to identify behaviors that can help connect an individual to respond in ways that are consistent with their values. Responses might include practical strategies such as pro-environmental behavior, activism, or emotion-focused strategies such as engaging with social support and activities in nature [49, 66, 91]. While this does not remove the threat, the individual integrates the conflict in a way that allows them to function and move forward with life in a meaningful way [91] so as to manage the threat as adaptively as possible. However, with the likely continued exposure of climate change related triggers in the future, the individual may continue to undergo an ongoing cycle of direct and indirect exposure to climate change triggers, making subsequent attempts to resolve or alleviate distress an ongoing process.

2.2 Maladaptive coping

Humans have the innate capacity to manage and resolve existential conflicts in personally meaningful ways [92]. However, there is potential for this process to be challenged when complicated by internal (e.g., pre-existing mental illness, a tendency for ruminative thought patterns or unhelpful coping strategies) and external (e.g., unexpected loss, migration, death) factors. When this occurs, an individual’s thoughts about climate change may be negatively biased (e.g., catastrophizing) or they may use unhelpful thought processes (e.g., ruminative, or excessive preoccupation styles of thinking) [49, 66]. Individuals may struggle to identify or implement strategies that could help mitigate their existential conflict, or they may succumb to habitual maladaptive behavior to avoid or alleviate negative feelings in the short term (e.g., excessive suppression, substance use, risk-taking behaviors) [18, 93, 94].

Alternatively, those who engage strategies to address climate change may do so to an unhelpful degree, making significant lifestyle changes that negatively impact their well-being in the long term by devoting much of their personal resources (e.g., time, energy) to climate action and experiencing ‘burnout’ or disillusionment as a result [18]. The loss of control ensued from unhelpful cognitive and behavioral patterns may then impair personal, social, and occupational domains. In turn, the feelings of climate anxiety and existential conflict are perpetuated and the individual may be less equipped to cope with future climate change triggers [95].

3 Discussion

3.1 Using the theoretical model of climate anxiety and coping in measurement

Developing a measure of psychological phenomena that is reliable, valid, and operational, is difficult without a consistent and comprehensive theoretical underpinning [96]. The theoretical model of climate anxiety and coping presented in the current paper draws together existing theories and measures to highlight climate anxiety as an affective construct, with potential correlates or sub-domains of (1) cognitive coping; (2) behavioral coping; and (3) functional impact. Existing measures may help to inform the development and selection of items that may assess these constructs, as well as any potential lower order constructs (see Table 2 for an example).

It is important for a climate anxiety measure to include both adaptive and maladaptive dimensions of cognitive and behavioral coping. The Measure of Affect Regulation (MARS) provides a useful example of a scale that measures frequency of 13 coping strategies, which differ based on whether the strategy is cognitive or behavioral, and whether the strategy focuses on resolving the situation or one’s mood [97]. Some examples of coping strategies include cognitive reappraisal (finding meaning or considering alternative perspectives), suppression (not allowing the expression of emotion), problem solving action (planning or acting to solve the problem), socializing or seeking help, and withdrawal or self-isolation. One study extended the MARS by including environmental strategies (e.g., going to favorite natural places). A climate anxiety measure might similarly assess coping across three dimensions: (1) cognitive vs. behavioral, (2) adaptive vs. maladaptive, and (3) focusing on resolving climate change, or the existential conflict/anxious feelings.

3.2 Identifying potential areas to intervene

Addressing the drivers of climate change will most significantly alleviate the negative implications for mental health and well-being. Yet, there is also increasing demand for interventions to support those who experience climate anxiety and the unmitigated impacts that climate change is having on mental health. Using a multiple needs framework, Bingley, Tran [36] identified that climate anxiety interventions can and do focus on meeting one or a combination of individual (e.g., improving individual well-being), social (e.g., fostering social connection), and environmental needs (e.g., pro-environmental attitude or behavior). As a starting platform, the theoretical model of climate anxiety and coping could be used to identify where to intervene in order to meet these needs or outcomes. More specifically, targeting cognitive or behavioral coping may be the mechanism for shifting levels of functioning across personal, social, and occupational domains. Interventions addressing cognitive coping may, for example, aim to support one to manage dysfunctional/unhelpful styles of thinking (individual needs), identify their shared values (social needs), or explore their role as it relates to climate change (environmental needs). Behaviorally focused interventions may, for example, focus on developing relaxation strategies (individual needs), fostering peer interaction or community building (social needs) or target climate mitigation through project engagement or decreasing one’s carbon footprint (environmental needs). These are few of the many ideas that can be developed based on the premise that coping will impact functioning, rather than emotion.

3.2.1 Ideas for interventions for maladaptive climate anxiety

Given the potential for maladaptive coping responses to climate anxiety, some individuals may need more comprehensive individual support. It is important, however, to note that little evidence exists for the efficacy of existing therapeutic interventions in supporting those who specifically experience climate anxiety. Potential interventions that could be drawn on to target cognitive or behavioral coping could include cognitive behavior therapy [66], acceptance and commitment therapy (accepting ecological emotions such as ecological grief or climate anxiety, connecting one to their values and committing to action) [7, 95], and interventions which may be existentially-focused, self-care focused [7, 31], emotion-focused [21], nature-based [6], as well as peer or group-based [21, 100]. As mentioned, research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these approaches in helping to strengthen adaptive coping and minimize impairments to functioning. Furthermore, such support should also consider the social and ecological influences that may shape adaptivity (e.g., geography, political landscape, culture) [29, 86].

As climate change impacts the world, there is an urgent need for intervention to be delivered beyond an individual receiving one-to-one support. Systemic interventions that aim to support public mental health can aim to promote adaptive cognitive and behavioral coping. For example, public health campaigns might consider reducing guilt, fear, and shame messaging, and instead communicating that climate anxiety is a shared experience that encompasses a range of different emotions that are understandable and can be responded to adaptively. Alternatively, media outlets that disseminate information on organizations, policies and initiatives that are working to address climate change could help to promote hope-based thinking and positive re-appraisals. Tangible strategies for coping could be given alongside these messages, particularly as they relate to meeting individual, social and environmental needs (e.g., online self-help tools for managing emotions, promoting community projects, funding climate mitigation projects) [7]. As with individual interventions, the focus of public-health level strategies is not to eliminate climate anxiety feelings, but to support planetary and human health and well-being.

3.3 Limitations and ideas for future research

The proposed theoretical model draws on the current state of evidence on climate anxiety along with well-established psychological theories of emotion and coping. It was developed based on a wide-ranging narrative review of existing research which included assessment of previous systematic reviews, and psychological theory brought together through clinical expertise of the contributing authors. Given the study was not a systematic review, this may have introduced a source of bias as to the way psychological concepts reviewed in the paper were used to construct the model presented. It must also be acknowledged that the theoretical model is untested, and empirical validation studies are greatly needed. Importantly, the model should be further informed and refined through future research and practice. Pathway analyses could help to evaluate potential associations between emotions about climate change, how individuals cognitively and behaviorally cope, and their relationship with functioning. Investigating how systemic factors influence climate anxiety and the capacity for coping will also help to determine how best to strengthen adaptive coping and over time, psychological resilience. Despite these limitations and the need for future research, this paper importantly responded to recommendations made by previous systematic reviews [12, 13, 30]. Specifically, the theoretical model of climate anxiety and coping helps to refine the conceptual understanding of climate anxiety and coping. From here, its application provides a way to assess psychological responses to climate change using measurement tools, which may in turn help in developing ways to support well-being as the climate crisis continues.

4 Conclusions

Within the theoretical model of climate anxiety and coping, competing viewpoints on the nature of climate anxiety converge. Specifically, climate anxiety may vary in adaptivity, intensity and severity. While existing measures capture maladaptive dimensions of climate anxiety, there is need for continued focus on developing a measure that can fully capture the spectrum of coping responses. Development of such a measure would (1) contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of how climate anxiety is experienced, (2) reduce potential inappropriate pathologizing of individuals who experience significant anxiety, yet who are responding to that anxiety in helpful ways; (3) identify those individuals who may be most in need of targeted mental health intervention; and (4) be used in future research to explore which factors may be associated with more or less adaptive responses. For interventions to be most effective, the range of experiences across cognitive, emotional, behavioral, existential, and systemic domains must be considered. Crucially, whether an intervention is delivered with the individual or at the public health level, focus should not be on eliminating climate anxiety, but in supporting the ability to channel that anxiety using cognitive and behavioral strategies to best meet the needs of the individual. With a more theoretically driven and robust conceptualization of climate anxiety, further research on climate anxiety may be able to better identify ways in which to support those adversely affected.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Manning C, Clayton S. Threats to mental health and wellbeing associated with climate change. In: Clayton S, Manning C, editors. Psychology and climate change. Academic Press; 2018. p. 217–44.

Hayes K, Blashki G, Wiseman J, Burke S, Reifels L. Climate change and mental health: risks, impacts and priority actions. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-018-0210-6.

Charlson F, Ali S, Benmarhnia T, Pearl M, Massazza A, Augustinavicius J, et al. Climate change and mental health: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094486.

Chen NT, Lin PH, Guo YL. Long-term exposure to high temperature associated with the incidence of major depressive disorder. Sci Total Environ. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.434.

Ayeb-Karlsson S. ‘When we were children we had dreams, then we came to Dhaka to survive’: urban stories connecting loss of wellbeing, displacement and (im)mobility. Clim Dev. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1777078.

Clayton S. Climate anxiety: psychological responses to climate change. J Anxiety Disord. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263.

Doherty TJ. 10—individual impacts and resilience. In: Clayton S, Manning C, editors. Psychology and climate change. Academic Press; 2018. p. 245–66.

Thompson HE. Climate “psychopathology.” Eur Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000433.

Panu P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197836.

Hickman C. We need to (find a way to) talk about … Eco-anxiety. J Soc Work Pract. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2020.1844166.

Budziszewska M, Jonsson SE. From climate anxiety to climate action: an existential perspective on climate change concerns within psychotherapy. J Humanist Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167821993243.

Coffey Y, Bhullar N, Durkin J, Islam MS, Usher K. Understanding eco-anxiety: a systematic scoping review of current literature and identified knowledge gaps. J Clim Change Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100047.

Soutar C, Wand APF. Understanding the spectrum of anxiety responses to climate change: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020990.

DeVellis RF, Thorpe CT. Scale development: theory and applications. SAGE Publications; 2021.

Richard JB, Ann F, Robert EOC. Public perceptions of global warming: United States and international perspectives. Clim Res. 1998;11(1):75–84.

Dunlap R. International attitudes towards environment and development. In: Bergesen H, Parmann G, editors. Yearbook of international co-operation on environment and development. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. p. 115–26.

Frumkin H. Beyond toxicity: human health and the natural environment. Am J Prev Med. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00317-2.

Dodds J. The psychology of climate anxiety. BJPsych Bulletin. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2021.18[Opensinanewwindow].

Ellison K. Conservation on the couch. Front Ecol Environ. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2008)6[168:COTC]2.0.CO;2.

Nobel J. Eco-anxiety: something else to worry about. The Philadelphia Inquirer; 2007.

Dailianis A. Eco-anxiety: a scoping review towards a clinical conceptualisation and therapeutic approach [thesis]: Auckland Univ. Techno.; 2020.

Fritze JG, Blashki GA, Burke S, Wiseman J. Hope, despair and transformation: climate change and the promotion of mental health and wellbeing. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-2-13.

Searle K, Gow K. Do concerns about climate change lead to distress? Int J Clim Chang Strateg Manag. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1108/17568691011089891.

Clayton S, Karazsia BT. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J Environ Psychol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101434.

Albrecht G. Chronic environmental change: emerging ‘psychoterratic’ syndromes. In: Weissbecker I, editor. Climate change and human well-being: global challenges and opportunities. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 43–56.

Pihkala P. Eco-anxiety and environmental education. Sustainability. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310149.

Pihkala P. Eco-anxiety, tragedy and hope: psychological and spiritual dimensions of climate change. Zygon. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/zygo.12407.

Helm SV, Pollitt A, Barnett MA, Curran MA, Craig ZR. Differentiating environmental concern in the context of psychological adaption to climate change. Glob Environ Change. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.11.012.

Ojala M, Cunsolo A, Ogunbode CA, Middleton J. Anxiety, worry, and grief in a time of environmental and climate crisis: a narrative review. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-022716.

Boluda-Verdú I, Senent-Valero M, Casas-Escolano M, Matijasevich A, Pastor-Valero M. Fear for the future: eco-anxiety and health implications, a systematic review. J Environ Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101904.

Baudon P, Jachens L. A scoping review of interventions for the treatment of eco-anxiety. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189636.

Koder J, Dunk J, Rhodes P. Climate distress: a review of current psychological research and practice. Sustainability. 2023;15:8115.

Hickman C, Marks E, Pihkala P, Clayton S, Lewandowski RE, Mayall EE, et al. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. Lancet Planet Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

Comtesse H, Ertl V, Hengst SMC, Rosner R, Smid GE. Ecological grief as a response to environmental change: a mental health risk or functional response? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020734.

Stanley SK, Hogg TL, Leviston Z, Walker I. From anger to action: differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing. J Clim Change Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100003.

Bingley WJ, Tran A, Boyd CP, Gibson K, Kalokerinos EK, Koval P, et al. A multiple needs framework for climate change anxiety interventions. Am Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001012.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Wang H, Safer DL, Cosentino M, Cooper R, Van Susteren L, Coren E, et al. Coping with eco-anxiety: an interdisciplinary perspective for collective learning and strategic communication. J Clim Change Health. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2023.100211.

Schwartz SEO, Benoit L, Clayton S, Parnes MF, Swenson L, Lowe SR. Climate change anxiety and mental health: environmental activism as buffer. Curr Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02735-6.

Daum I, Markowitsch HJ, Vandekerckhove M. Neurobiological basis of emotions. In: Markowitsch HJ, Röttger-Rössler B, editors. Emotions as bio-cultural processes. New York: Springer; 2009. p. 111–38.

Harth NS. Affect, (group-based) emotions, and climate change action. Curr Opin in Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.018.

Keltner D, Sauter D, Tracy J, Cowen A. Emotional expression: advances in basic emotion theory. J Nonverbal Behav. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-019-00293-3.

Steimer T. The biology of fear- and anxiety-related behaviors. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2002. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2002.4.3/tsteimer.

Hebert EA, Dugas MJ. Behavioral experiments for intolerance of uncertainty: challenging the unknown in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.07.007.

Grupe DW, Nitschke JB. Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: an integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3524.

Lewis J. In the room with climate anxiety. Psychiatr Times. 2018; 35(11). https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/room-climate-anxiety.

Ogunbode CA, Doran R, Hanss D, Ojala M, Salmela-Aro K, van den Broek KL, et al. Climate anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental action: correlates of negative emotional responses to climate change in 32 countries. J Environ Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101887.

Sciberras E, Fernando JW. Climate change-related worry among Australian adolescents: an eight-year longitudinal study. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12521.

Crandon TJ, Scott JG, Charlson FJ, Thomas HJ. Coping with climate anxiety: impacts on functioning in Australian adolescents. Submitted. 2023.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984.

Stanisławski K. The coping circumplex model: an integrative model of the structure of coping with stress. Front Psychol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00694.

Ojala M. Regulating worry, promoting hope: how do children, adolescents, and young adults cope with climate change? Int J Environ Sci Educ. 2012;7(4):537–61.

Ojala M. Coping with climate change among adolescents: implications for subjective well-being and environmental engagement. Sustainability. 2013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5052191.

Ojala M, Bengtsson H. Young people’s coping strategies concerning climate change: relations to perceived communication with parents and friends and proenvironmental behavior. Environ Behav. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391651876389.

Pihkala P. The process of eco-anxiety and ecological grief: a narrative review and a new proposal. Sustainability. 2022;14:16628.

Cunsolo A, Ellis NR. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat Clim Change. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2.

Schneider CR, Zaval L, Markowitz EM. Positive emotions and climate change. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.04.009.

Ojala M. Adolescents’ worries about environmental risks: subjective well-being, values, and existential dimensions. J Youth Stud. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260500261934.

Albrecht GA. Negating solastalgia: an emotional revolution from the Anthropocene to the Symbiocene. Am Imago. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1353/aim.2020.0001.

Kleres J, Wettergren Å. Fear, hope, anger, and guilt in climate activism. Soc Mov Stud. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2017.1344546.

Okon-Singer H, Hendler T, Pessoa L, Shackman AJ. The neurobiology of emotion–cognition interactions: fundamental questions and strategies for future research. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00058.

Niedenthal PM, Ric F. Psychology of emotion. London: Taylor & Francis Group; 2017.

Innocenti M, Santarelli G, Faggi V, Castellini G, Manelli I, Magrini G, et al. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale. J Clim Change Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100080.

Wullenkord M, Toger J, Hamann KR, Loy L, Reese G. Anxiety and climate change: a validation of the climate anxiety scale in a German-speaking quota sample and an investigation of psychological correlates. Clim Change. 2021. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/76ez2.

Hogg T, Stanley S, O’Brien L, Wilson M, Watsford C. The Hogg eco-anxiety scale: development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Glob Environ Change. 2021. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/rxudb.

Burke S, Blashki G. Climate change anxiety and our mental health. In: Climate health and courage. Melbourne: Future Leaders; 2020. https://www.futureleaders.com.au/book_chapters/pdf/Climate-Health-and-Courage/Susie-Burke-and-Grant-Blashki.pdf.

Lutz PK, Passmore H-A, Howell AJ, Zelenski JM, Yang Y, Richardson M. The continuum of eco-anxiety responses: a preliminary investigation of its nomological network. Collabra: Psychology. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.67838.

Beck AT, Clark DA. An information processing model of anxiety: automatic and strategic processes. Behav Res Ther. 1997. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00069-1.

Sangervo J, Jylhä KM, Pihkala P. Climate anxiety: conceptual considerations, and connections with climate hope and action. Glob Environ Chang. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102569.

Ojala M. How do children, adolescents, and young adults relate to climate change? Implications for developmental psychology. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.02.004.

Verplanken B, Marks E, Dobromir AI. On the nature of eco-anxiety: How constructive or unconstructive is habitual worry about global warming? J Environ Psychol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101528.

Wells A. Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. New York: Guilford Publications; 2011.

Beck AT, Haigh EAP. Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: the generic cognitive model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734.

Ramos-Cejudo J, Salguero JM. Negative metacognitive beliefs moderate the influence of perceived stress and anxiety in long-term anxiety. Psychiatry Res. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.056.

Pollyana Caldeira L, Tiago Costa G, da Luiz Carlos Ferreira S, Teixeira-Silva F. Trait vs. state anxiety in different threatening situations. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychother. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2016-0044.

Materia CJ. Climate state anxiety and connectedness to nature in rural Tasmania [thesis]: Univ. Tasmania; 2016.

Yalom ID, Josselson R. Existential psychotherapy. In: Wedding D, Corsini RJ, editors. Current psychotherapies. 10th ed. California: Cengage Learning; 2013.

Weems CF, Costa NM, Dehon C, Berman SL. Paul Tillich’s theory of existential anxiety: a preliminary conceptual and empirical examination. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800412331318616.

Pihkala P. Death, the environment, and theology. Dialog. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/dial.12437.

Yalom ID. Existential psychotherapy. Michigan: Basic Books; 1980.

Ballman C. Emotions and actions: eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behaviours [thesis]: Univ. Regina; 2020.

Chhokar K, Dua S, Taylor N, Boyes E, Stanisstreet M. Senior secondary Indian students’ views about global warming, and their implications for education. Sci Educ. 2012;23(2):133–49.

Gregersen T, Doran R, Böhm G, Tvinnereim E, Poortinga W. Political orientation moderates the relationship between climate change beliefs and worry about climate change. Front Psychol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01573.

Clayton S. Mental health risk and resilience among climate scientists. Nat Clim Change. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0123-z.

Kubo T, Tsuge T, Abe H, Yamano H. Understanding island residents’ anxiety about impacts caused by climate change using Best-Worst Scaling: a case study of Amami islands. Japan Sustain. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0640-8.

Crandon TJ, Scott JG, Charlson FJ, Thomas HJ. A social-ecological perspective of climate anxiety in children and adolescents. Nat Clim Change. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01251-y.

Crandon TJ, Dey C, Scott JG, Thomas HJ, Ali S, Charlson FJ. The clinical implications of climate change for mental health. Nat Hum Behav. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01477-6.

Adams M. Critical psychologies and climate change. Curr Opin in Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.01.007.

Gislason MK, Kennedy AM, Witham SM. The interplay between social and ecological determinants of mental health for children and youth in the climate crisis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094573.

Ingle HE, Mikulewicz M. Mental health and climate change: tackling invisible injustice. The Lancet Planet Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30081-4.

Stollberg J, Jonas E. Existential threat as a challenge for individual and collective engagement: climate change and the motivation to act. Curr Opin in Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.10.004.

Wong PTP. Existential positive psychology and integrative meaning therapy. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2020.1814703.

Swerdlow BA, Pearlstein JG, Sandel DB, Mauss IB, Johnson SL. Maladaptive behavior and affect regulation: a functionalist perspective. Emotion. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000660.

Boehme S, Biehl SC, Mühlberger A. Effects of differential strategies of emotion regulation. Brain Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9090225.

Koger SM. A burgeoning ecopsychological recovery movement. Ecopsychology. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2015.0021.

DeVellis RF, Thorpe CT. Scale development: theory and applications. Bickman L, Rog DJ, editors. California: SAGE Publications; 2021.

Korpela KM, Pasanen T, Repo V, Hartig T, Staats H, Mason M, et al. Environmental strategies of effect regulation and their associations with subjective well-being. Front Psychol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00562.

Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U.

Knowles SR, Apputhurai P, Bates G. Development and validation of the brief unhelpful thoughts scale (BUTs). J Psychol Psychother Res. 2017. https://doi.org/10.12974/2313-1047.2017.04.02.1.

Gillespie S. Climate change and psyche: conversations with and through dreams. Int J Mult Res. 2013. https://doi.org/10.5172/mra.2013.7.3.343.

Funding

T.C. is supported by the Child and Youth Mental Health Research Group PhD Scholarship. H.T. and F.C. are supported by the Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research which is funded by the Queensland Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.C. led the writing of the article, with J.S., F.C., and H.T., contributing to writing at all stages. All authors contributed to conceptualization and the editing process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Crandon, T.J., Scott, J.G., Charlson, F.J. et al. A theoretical model of climate anxiety and coping. Discov Psychol 4, 94 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00212-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00212-8