Abstract

Research has demonstrated children in out-of-home care have experienced trauma and a significant proportion are in need of behavioral health services (e.g. Casaneuva et al., NSCAW II baseline report: Child well-being, US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC, 2011). Accessing services requires interagency coordination between child welfare and behavioral health professionals; however, challenges to coordination and collaboration may result in lack of service utilization for many youth (Hanson et al. 2016). Utilizing a mixed methodological approach, this paper describes the results of a study conducted five years after full state-wide implementation of processes designed to promote the use of evidence-based practices to inform decision-making for youth dually served by the child welfare and behavioral health systems. Outcomes from the study were used to develop strategies to address programmatic concerns and reinforce implementation supports. Study findings may aid organizations seeking to reinforce data-informed practices and employ strategies for addressing barriers at the worker and agency level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Children entering out-of-home care (OOHC) are at greater risk for significant trauma and resultant behavioral health challenges [12]. In a study conducted by Griffin and colleagues [23], 95% of youth in OOHC experienced at least one type of trauma. However, their behavioral health needs often go untreated [1, 32]. Child welfare agencies who are responsible for their care must identify potential behavioral health needs upon placement so that referrals can be made, and appropriate trauma-based treatment is obtained [44]. Given the exigency to address the trauma experienced by these youth, a trauma-informed care approach emphasizing interagency or system collaboration is required to meet those needs [16].

In response to the collaboration necessary to address the trauma services required for children in care, the Children’s Bureau funded a series of grants to install standardized screening and functional assessment of children in OOHC through collaborative initiatives of child welfare and behavioral health systems (e.g. [29, 30, 34, 55]). Project SAFESPACE was initially a federal grant project that concluded in 2018. The interventions that were implemented during the federal grant have since been sustained statewide for five years, and designed to promote the use of evidence-based practices to inform decision-making. For this state-wide initiative, child welfare (CW) workers complete universal screenings for trauma and behavioral health needs for youth entering OOHC using standardized instruments measuring trauma experiences and behavioral health symptomatology, and behavioral health (BH) clinicians complete a standardized functional assessment and measurement of progress over time using the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strength tool [41]. Subsequently, these youth level data are used to inform treatment selection and case planning. The purpose of this paper is to describe the results of a mixed methods study conducted five years after full implementation of Project SAFESPACE to identify factors that contributed to implementation drift and those that could influence greater fidelity to underutilized behavioral health interventions.

1.1 Interagency collaboration between child welfare and behavioral health

CW workers are not mental health professionals and rely on the expertise of (BH) clinicians to assess the mental health treatment a child requires [47]. However, child welfare and behavioral health organizations can face obstacles related to information gathering and exchange that may inhibit using relevant data to inform decision-making regarding placement and treatment decisions for youth in OOHC [15, 26, 27]. Behavioral health agencies reported they rarely receive necessary information during the referral process to assess a child’s trauma history and determine treatment needs [35]. It is likely that CW workers do not understand the level and type of information that would be useful to their colleagues in partner agencies [30].

The establishment of interagency policies or agreements to guide information sharing may be necessary to secure needed treatment [17, 20, 28]. Technological solutions can be developed to facilitate interagency information exchange to meet children’s needs [43]. Initiatives designed to facilitate interagency coordination and collaboration processes for behavioral health services for children in OOHC have been implemented at a growing rate (e.g. [5, 13, 48, 49]). Kerns and colleagues [30] found standardized screening and interagency collaborative behaviors resulted in increased receipt of mental health services. Other studies found service coordination resulted in improved access to services and evidence-based treatments [25], integration of therapeutic interventions [11], and improvement in MH symptoms [4, 6, 45].

1.2 Standardized screening and functional assessment to inform decision-making

The growth in use of standardized instruments to inform child welfare and behavioral health decisions has increased over the past two decades [14, 31, 42, 53]. Use of standardized screening and assessment tools may be associated with early identification of behavioral health needs [9]. Standardized screening by CW workers has been found to identify behavioral health needs and yield access to treatment which may result in reduced risk of placement disruption [2, 52]. Similarly, standardized assessment is a form of evidence-based clinical practice that supports case conceptualization and treatment decision making by behavioral health clinicians [40]. Research suggests use of standardized assessment tools are more useful for treatment planning compared to unstructured assessment techniques [3]. Use of standardized screening by CW workers and functional assessment by BH clinicians may support referral and treatment decisions as well as facilitate interagency information exchange that supports child wellbeing.

1.3 Use of implementation studies to promote intervention fidelity

The use of implementation science to promote installation and ongoing use of practice initiatives has become the norm, and can be defined as studying the factors that promote or impede the complete use of practice innovations. Blasé and Fixsen [7, 8] asserted that in order to achieve desired outcomes from practice initiatives, promising innovations can be multiplied through intentionally applied implementation supports. The organizational, or inter-organizational, context in which practice initiatives are implemented is also an important factor and should be examined [51]. A number of implementation frameworks have been established (e.g. [38, 39]). The Active Implementation Framework used for installation of Project SAFESPACE [36] describes the unique aspects of each stage of implementation (including full implementation in which the initiative has become day-to-day practice), the drivers that facilitate fidelity, and the use of improvement cycles involving tracking implementation and utilizing course correction strategies when required.

Implementation studies associated with interagency initiatives to promote receipt of behavioral health services by children in OOHC have begun to emerge to assist the field in understanding how to promote the optimal opportunity for success (e.g. [2]). One such study of a specific collaborative behavioral health initiative documented successful implementation including interagency training, supervisor and leadership support, establishment of referral, communication processes, and buy in from relevant staff [22].

1.4 The current project

1.4.1 Screening and assessment process

When a child enters OOHC (ages 0–17), the CW worker completes the appropriate screeners based on the child’s age within 10 business days of entry. The screening instruments include the Young Child PTSD Checklist A (ages 0–6), Young Child PTSD Checklist B (ages 1–6) [19], Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (ages 2–17) [21], Upsetting Events Survey (ages 7–17) [33], Child PTSD Symptom Scale V (ages 7–17) [19], and CRAFFT (ages 12–17) [18]. If the child meets clinical criteria for further assessment based on the outcome of the screening, the child is referred to a behavioral health provider agency for a CANS Assessment. The BH clinician has thirty days to complete the initial CANS, which is used to inform evidenced-based treatment (EBT) selection and case planning. As long as the child receives services from the agency, CANS updates are completed every 90 days. If a child does not meet clinical criteria when the initial screener is completed, there are several circumstances that would indicate the need for additional screening including placement disruption, permanency goal change, repeat maltreatment, and any time the worker feels that screening and assessment would benefit the child. The intended outcome of these process is to identify behavioral health needs and enhanced placement stability and permanency. See Fig. 1 for an overview of the screening and assessment process.

A technological interface enables direct transfer of data between agencies and the data systems each employ. Demographic data regarding the children to be assessed are transferred to the information system utilized by BH clinicians, and the results of the CANS assessment including recommendations for treatment and, progress made for children in treatment are transferred into the CW management information system. This exchange of information is intended to facilitate evidence-based decision-making by both groups.

Less is known about the effectiveness of implementation strategies in facilitating interagency BH initiatives [25]. One study examining an initiative to promote collaboration between CW and BH found that projects requiring substantial change may not see the outcomes associated with enhanced collaboration until long after implementation has been achieved ([49]). Although trauma screening and CANS assessment practices have been fully in place for five years, implementation compliance was inconsistent creating a need for further study. Data for the current mixed methods study were collected to assess the continued use of these practices to inform decision-making, factors influencing ongoing implementation and ways these processes can be improved. There are three research questions in which this study was designed to answer:

-

1)

To what extent are screening and assessment practices being implemented with fidelity to protocol?

-

2)

What are factors influencing screening and assessment practices?

-

3)

What are ways screening and assessment can be improved?

2 Methodology

This mixed methods study combined analysis of aggregate data collected from the CW information management system with data from focus groups of professionals working in CW and BH agencies. Institutional review board approval was obtained for the study. Before each focus group, participants provided consent to participate.

2.1 Administrative data analysis

To answer research question 1, the public CW agency provided the research team with an administrative dataset which included child level data associated with screening and assessment over the five years since the conclusion of the federal project, at which time the state reached full implementation in all service regions. Once data were cleaned, a dichotomous variable was created for each screening instrument with yes = the child met the clinical threshold for a referral to behavioral health and no = the child did not meet the clinical threshold. A second dichotomous variable was created with yes = the child received a CANS Assessment and no = the child did not receive a CANS Assessment. To determine the percent of children who were screened, the number of children in OOHC were compared with the number of children who were screened by one or more of the screening instruments. To determine the proportion of children who met clinical threshold for a CANS assessment, the number of children screened were compared with the number of children who met clinical threshold on one or more screening instruments. To determine the proportion of children who received a CANS assessment, the number of children who met the clinical threshold on one or more screening instruments were compared with the number of children who received a CANS assessment. Each of these indicators were analyzed by year from June 1, 2018, through December 31, 2022, to assess change over time.

2.2 Focus groups

2.2.1 Procedures

To answer research questions 2 and 3 focus groups were conducted with individuals who worked for the CW and BH agencies. The project staff, BH agency leads and CW regional administrators promoted participation in the focus groups among staff in their organizations. Potential participants received an email inviting them to register to participate in a virtual focus group, with the informed consent document attached. Focus groups were completed by university employees unaffiliated with the project. Data were transcribed and cleaned before being turned over to the research team for analysis. Researchers employed a semi-structured interview guide using a priori codes developed from intervention fidelity markers. Questions asked of participants were parallel in that questions asked of child welfare focused on the screening process while those asked of behavioral health focused on the assessment process. In addition to practice specific questions, participants were asked about their understanding of the purpose of the practice they were intended to perform, what factors influenced the specific practice (facilitators and barriers), how information was gathered to inform the practice and from whom, and the extent to which the information gathered or provided by the other professionals were used to inform decision-making.

2.2.2 Participants

Focus groups were conducted with a purposive sample of CW workers and BH clinicians from each of the nine regions of the state. Eleven focus groups were completed with BH clinicians from private child placing agencies, community mental health agencies, and independent providers. An additional eleven focus groups were conducted with CW workers in each of nine service regions. Two groups were held with CW staff who serve as liaisons between the CW and BH agencies for the screening and assessment process See Table 1 for information about the participants.

2.3 Data analysis

The purpose of this study was exploratory in nature, and we did not attempt to generate or confirm theory or hypotheses. Instead, thematic analysis was conducted to describe the perceptions of participants in such a way that could be useful to the field. Written transcripts (n = 24 artifacts) were de-identified and uploaded to the Dedoose qualitative analysis software which was used to code and categorize the data into themes within the responses to each of the questions [24]. Line by line coding was conducted using Braun and Clarke’s [10] six stage process: initial review of data to familiarize the researcher with it overall, generating preliminary open codes, identifying, reviewing and defining themes, and reporting of results. Themes were generated inductively and refined through iterative review and revision of coding through constant comparative analysis [46]. Memoing was used to keep a record of the decisions and changes made during the initial and subsequent coding processes. To demonstrate the extent to which specific themes were observed across multiple agencies, frequency counts were used to identify the number of times that participants mentioned certain themes [37].To mitigate bias, three researchers met weekly to code and categorize data into themes within the responses to each of the interview guide questions.

3 Findings

3.1 Administrative data analysis

For analysis of data related to screening, of the 34,863 children for whom data were received, 13,061were excluded for reasons such as being screened before full implementation began (full implementation was reached on May 31, 2018, thus data for this year are from June 1, 2018 through December 31, 2018) or being in OOHC less time than would yield a screening. Screening analysis included 21,802 children and functional assessment analysis included 16,170 children, the difference representing the number of children who were screened by child welfare and did not meet clinical cut off on one or more screening instruments.

3.1.1 Children screened by child welfare

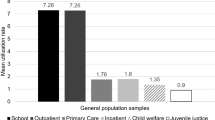

The overall number of children in OOHC were compared with the number of children who were screened by one or more of the screening instruments. See Table 2 for findings. On average, over half of children in OOHC were screened for trauma or behavioral symptoms.

3.1.2 Children who met clinical threshold

The number of children screened were compared with the number of children who met clinical threshold on one or more of the screening instruments. See Table 3 for findings. Over time, there was a consistent increase in the percent of children who were screened for trauma or behavioral symptoms and met the clinical threshold on one or more screening instruments.

3.1.3 Children who received a CANS assessment

The number of children who met clinical threshold on one or more screening instruments were compared with the number of children who received a CANS assessment. See Table 4 for findings. As seen in Table 4, the number of children who met the clinical threshold for a referral to behavioral health and subsequent CANS assessment increased over time. However, the percent of children who were eligible for a CANS assessment and actually received one decreased over time. There was a consistent decrease in percent of children who met clinical threshold on one or more screening instruments and then received a CANS assessment.

3.2 Focus groups

A summary of significant themes generated from analysis of indications of fidelity to screening and assessment practices as well as factors which may be influencing implementation is included below. Quotes are provided to illustrate the nature of identified themes. To demonstrate the extent to which specific themes were observed across multiple agencies, frequency counts were used to identify the number of times participants mentioned certain themes and are provided in parentheses after the theme or subtheme. The themes reported here are focused on those that may be useful to understand how to best support fidelity and implementation of such practices. Only those themes with five or more observances are provided.

3.2.1 Understanding of the purpose of the practice

Screening. CW workers had a bifurcated understanding of the purpose of the screening process. While certainly assessment and treatment are related, there is a nuance here that is notable.

Screening Informs Referral to Behavioral Health for Treatment (16). Twice as many CW workers viewed screening as a gateway to treatment.

To assess the past history and trauma of a child coming into foster care to see what services and treatment track they're going to need.

Screening Informs Referral to Behavioral Health for Assessment (8). Others recognized that screening is to determine if a behavioral health assessment of the child was indicated.

To assess the children and see what trauma they've been through or what experiences they've had and what they might need, and then with the CANS assessment, it checks it overtime, so to see what progress they've made.

A quick, almost temperature check to see if any further assessments need to be completed…a less invasive quick check-in to see if anything needs further observation and assessment.

Assessment. Behavioral health clinicians were asked what their understanding was regarding the purpose of the periodic use of the CANS. Five different, but certainly related, purposes were offered.

Facilitate Getting Services Children Need/Informing Treatment (20). The strongest theme related to determining and responding to clinical needs of the child.

The CANS assessment gives us this kind of shared understanding across every facet for the adolescent as to what this child is needing and where their strengths are.

Facilitate Communication Between Child Welfare and Behavioral Health and Courts (15). The second most common response involved facilitating information exchange as opposed to a more clinical purpose.

It gives the workers, and the judge the same language that I have in understanding treatments, barriers, and strengths the same way that I do.

Periodic Measurement of Needs/Risk (9). After the initial assessment, some noted that completing the CANS on a regular basis enabled the clinician to revisit the child’s needs.

I’m a big supporter of when it comes to the reassessment of the CANS. I definitely see the value in that. Looking at being able to show … how things have improved, or …maybe have worsened in certain areas. I definitely see the value in that, and to be Abe to lay that out for the clients to see how things have changed.

Track Progress/Outcomes (8). Relatedly, some recognized that by periodically completing the CANS they could measure the extent to which the child was making progress on clinical outcomes or their functioning.

[The CANS] is supposed to aid in case care planning really. Seeing what that child needs, serve as a baseline, the initial, and then to monitor progress.

3.2.2 Information gathered to inform the practice

Screening. A few respondents stated they had one source of information, which was sometimes the case file or prior CW workers. However, the vast majority of respondents spoke about having a multi-pronged approach to completing the screening instruments: the child (21), the biological family (19), the case file or other CW workers (13), and school or collateral contacts (7).

I typically do the screeners with the older children and even middle school and elementary school. I think [a] barrier though, is honesty, especially the older children. So, I typically try to go back over some of these questions also with parents.

I usually just talk to the child. I do try to build a rapport first, if they're younger you have to kind of break it down to where it's age appropriate. If [the youth are] nonverbal you have to get that information from the caregiver.

In order to make it easier to complete in real time and also reduce duplicative data entry, the agency enabled workers to use computers or other devices directly to do the screener. While eleven respondents reported using computers or devices, the majority (20) conduct paper-based screening—printing off the form, completing it, and then entering it into the computer system.

I've done both. I've found that paper works because going in there the first time with the tablet is kind of intimidating. If it's a baby, I’m gonna take my tablet. If it's a 16-year-old, I'm gonna take paperwork so they can see what I'm doing and be a part of it.

I always try to use my tablet whenever I'm going over the questions because it's easier to input the information as I'm asking the questions. And then I don't have to do an extra step…that's one piece that's out of the way.

Assessment. BH clinicians were asked how much they actually use screening results in functional assessment as intended. Respondents were split on this resulting in two subthemes.

Providers Do Use Screener Information to Inform the CANS Assessment (13).

It's a wealth of information. I think that [the clinicians] are looking the screeners over before they meet with the family, then helping them understand the background. The client doesn’t have to tell their story again and we can be more sensitive to the things that are going on. We file all that in electronic medical records so we can reference the screeners.

I download them and send them to our staff, and we review all those things together…There is information in there that sometimes we didn't know…It’s a collaboration process and that’s key with all of this.

Important Information is not Provided in the Screening Information. Some BH clinicians indicated that they did not receive information that would be useful in the assessment (12).

Recently, I got a boy who was supposed to be getting sexual offender programming, and we probably wouldn't even have accepted [him] if we had known that because we don't have anybody at this time that can do that treatment. But that information was nowhere, and it wasn't until we actually two week-ed him and then got into a meeting where they’re questioning why he isn't getting services. So that also makes the agency look bad, because we never had the information to be able to provide him the appropriate services.

The information we get for our CANS referrals are pretty much just demographic and noting that they may have flagged rated high in this area. That would denote why they needed a CANS assessment, but it doesn't tell us what they flagged high in or why, so the information we get that's not just demographic related it doesn't really help us inform treatment in any way.

BH clinicians were asked from whom they obtain information to complete the CANS. Most frequently listed were families (28), followed by the youth (17), other or previous assessments (17), CW workers 16, and school personnel (6).

3.2.3 Facilitators of implementation

Assessment. Clinicians described three factors or processes that facilitated completion of the functional assessment.

Internal Tracking Systems or Identified Staff Who Manage the CANS Processes (18). The most common response provided examples of processes established in BH agencies to facilitate the process.

Every time a quarterly [assessment] is due for the level of care for the youth then we expect the CANS to be done as well.

I make my own CANS due date a week prior to when it's actually due. That way I can get it to the therapist and also consult with them, so that we can use things directly from the CANS to come up with goals and objectives for the treatment plans.

Assistance from the CW Agency Liaison (10). These liaisons served as an important source of information from BH clinicians especially when they had difficulty reaching CW workers.

I’ll usually just shoot (CW Agency Liaison) an email and say, hey, do you have a child ID number for this kid? And usually, I mean I'd say 99.8% of the time she does, so I will say that (CW Agency Liaison) is a huge resource for us. I will say that I love her so much.

Need to be Re-certified in Use of the CANS or Attend Training (5). Periodic skill refreshers were seen as facilitating practice.

So now I added it to the end of the training to where we all sit together and take our test. I can have folks be certified and that way all of our time is beneficial.

3.2.4 Barriers to implementation

Since barriers often referred generally to both screening and assessment, all of the themes from both groups are listed here together with reference to whether it was based on CW or BH perceptions.

BH Clinicians do not Receive Screeners or Other Important Information in the Referral Process to Inform the CANS (40). While clearly this is a concern shared across BH providers, variations of the theme are noted. Some noted rarely receiving screeners from the CW worker at all.

Honestly, if we get a Screener, it's usually after the 1st 30 days and so it was kind of irrelevant and so we've already done the CANS, so it just gets uploaded in their file. Really don't really look at it.

Others struggled with not getting critical information for the behavioral health assessment.

So a lot of those times we’re not even given the information as to why they're removed, other than there was a trauma. We don't know a lot of details about what that child's been through with that family … 'cause sometimes children are placed fairly quickly.

In other cases, the information received was out of date or inaccurate.

Recently I've noticed, and this doesn't happen like very often, but sometimes we will have the [referral form] completely inaccurate [regarding]the kid. …Maybe it was accurate at one point, but we had a kid that really struggled with hygiene and that was very apparent. But on the [form] it said that like they really took pride in their appearance and that they worked really hard on personal hygiene. So, it was just like completely opposite. And come to find out it had been something that they had been struggling with for a while. So that's kind of one thing that is a little bit tougher here because it just hits hard with the CANS assessment–kind of nowhere to start if like the problems aren’t identified.

Concerns About the Quality of the CANS Assessment or Clinician (34). The most common barrier reported by CW workers related to their distrust of the quality of the assessment conducted or the clinician who completed it. Some of this may include an underlying factor related to the CW worker’s lack of understanding of how to use the information in the CANS report.

The CANS have no information. For staff it's like, what is the purpose? You send [kids] to these agencies and then we're supposed to get the CANS that's supposed to help us with case planning, and it literally has no information. Maybe one sentence at the end.

I don't see that the therapist is taking the initiative to try [and]ask about history [or] about what's going on. [For example] ‘What is up with the parents? Are the parents working a case plan? What does that look like? Let's bring the parents in and try to work on family therapy’. It's a disservice to our kids.

BH Clinicians have Concerns Regarding the Established Timeframe for CANS Completion (24). Some of these were assertions that the timeframe is problematic for clinical reasons while others point to workload and agency capacity.

Then they're kind of in that honeymoon period [where] you can do the CANS and you know things look like it's pretty smooth sailing. And then just a couple weeks, if not less than that, the honeymoon period is over and you're seeing all of these behaviors that truly exist, and then you're like… Shoot, you know my CANS is out the window because you just didn't have the information and they were in that phase where they weren't showing true behaviors yet.

Our agency had policies set in place at the treatment plans complete within a certain time frame, and so typically … the clinician could complete on that first visit, … a 45 minute to an hour session is not going to be conducive to do everything else you got to do and do a CANS assessment as well. Just it's not possible.

Concerns About Timing of Screening or Assessment (13). Another barrier noted by CW related to the time frames within which the policy dictated that the process occur.

[For] the screeners, give [us] more time to get them done. Lots of times, at removal, the parent is irate.

CW Worker Workload and Turnover (22). A significant barrier to implementation had to do with staff vacancies and workload, preventing them from conducting the CANS process as intended.

We've got either very seasoned workers [who] are really, really tired, or you've got new staff [who] are panicking because they're like, ‘Oh my God, what’d I walk into’, because it's just, it's kind of a bit of a mass mania right now of robbing Peter to pay Paul kind of thing.

Lack of Understanding of the Process (34). Some respondents within this theme indicated CW worker confusion in terms of the intervention protocols, but others related to not seeing screening and assessment having value to them in meeting the needs of the child. Some saw this as just another paperwork requirement rather than a valuable clinical tool. The first quote came from a liaison whose job it was to track referrals to BH provider agencies for assessment.

I’ve had specialized investigators come to me and say, ‘Hey, can you show me where to find the screener information in [the computer system]?’ ‘Can you show me how to go about filling this out?’ We're admin specialists, we should not be training workers how to do their jobs. I think there's a big difference in interpretation, as far as how to answer some of the [screener] questions. One of our specialists brought to my attention on the screener that checks for trauma, a lot of the [workers] are marking ‘no because they’re not thinking of the fact that just for a child to be removed from a home, that in itself is trauma.

Similarly, a group of BH clinician responses indicated they too do not understand the screening and assessment process, or perhaps see value in it.

Wanting more training on how to understand when you're doing the comparative analysis and you're seeing the numbers go up and down. Like how significant of a deviation is that or of a success is that? Maybe more training just around how do we, when we're looking reflectively at them, how should we be interpreting that?

Technology/Computer Challenges (18). Some of these responses related to old or inadequate computer equipment in the BH agencies. Others related to issues associated with the functioning of or inaccurate information in the data system into which CANS or referral data is entered.

Unless you actually run the reports showing that a CANS is due for reassessment or discharge … no one is going to let you know. … And it's just affecting their deficiency reports and stuff like that. …You don't get an automated message. … so this system itself is not terribly user friendly either.

Concerns About Screening Younger or Low Functioning Youth (17). The next theme involved CW workers believing that screening was inappropriate for certain children, despite policy.

I don’t think [the screener] should be a requirement for children, maybe under the age of three or under the age of two. Sometimes we have children that are literally one month old that we're referring for mental health. It's a lot of work on the workers time because they have to fill out a 15-page referral for an infant. When really, what type of [mental health] service are you providing to an infant? I wish that that wasn't a requirement, but unfortunately our policy mandates that.

Questions on the CANS Don’t Fit Specific Children (7). Similar to CW workers questioning whether screening is appropriate for young children, BH clinicians question using the CANS for young or developmentally delayed children.

Once a child is over the age of 4 and we switched to the older version of the CANS, there are some things that don't necessarily apply, especially if there are developmental delays. [The CANS questions] don't seem to match kids who are developmentally delayed.

BH Clinicians see the CANS as Duplicative of Other Required Assessments/Screeners in their Agency (15). For some agencies, clinicians were required to complete additional tools and here was not an appreciation of the added value of the CANS.

We have approached our agency higher ups to see if we could utilize the CANS as our assessment and alleviate some of the other assessments [to] not to have so much cumbersome paperwork on the client. We’ve had several meetings with the board to figure that out. It’s not been approved yet, but we’re constantly advocating for that.

BH Clinicians Don’t Find the CANS Useful in Treatment (14). Some did not see standardized measurement such as this process as assisting them in providing clinical services.

I think people resent it, and they're just marking stuff down. It's not … taken seriously anymore.

Treatment plans are designed to be person-centered. If the client’s personal goals are not in line with what we get from the CANS, then its [not person-centered].

Concerns About Items on the Screening Instruments (13). Some responses related to the wording of items on the instruments.

When the workers are [completing the screener] with the family, the family members don't understand why we're doing it and they're trying to break it down into layman's terms, but it's hard. The questions that talk about sexual abuse; they feel they have to reword it for them to understand because they don't really get it.

BH Clinicians Think the CANS is Subjective (12). Some did not find the CANS to provide an objective measurement.

I struggle using the CANS for that measurement since. It’s everyone’s opinions.

Difficulty Accessing Information from Child or the Parents to Complete Screening (25). Some CW workers indicated that parents are sometimes unavailable to inform the process, or children are unavailable.

We have kids [who] are moving very rapidly. I fill out the paperwork [and] send them for their CANS, then three months later realize there’s no CANS completed. Then you find out the kid’s had three placement changes since that time, and nobody lets us know.”

When kids [who] are AWOL, you’re not able to do a screener with them, so the worker gets dinged on reports because they can’t do the screener.

I was in a situation where the parents were under the influence so much [so] that they were like zombies that evening. They couldn’t even tell me where the kid went to the doctor. I didn’t have hardly any information to go off of and there was no [other] family.

Relatedly, BH clinicians also expressed concerns about accessing the family when scheduling a CANS assessment.

I think sometimes one of the barriers is, you know, if they’re out of home placement, we may not have a really good number contact for that biological family. And if the goal is for them to return back home, we want to be able to, you know, include that caregiver, as part of that assessment, to help determine some of those goals for the social worker, and so it could just be hard sometimes making contact with some of the families.

Availability of CANS Assessors (11). Some agencies did not have enough clinicians who were certified to use the CANS.

I think one of the limitations is having few people trained in it, and oftentimes those clinicians aren’t even … the identified provider for somebody ongoing. … But then if it’s identified that they need a CANS, they’ve been shuffled off to another clinician to do that. So, sometimes rapport is a little bit of a barrier.

Providers are hesitant to use assessments completed by others (7). A few noted that they were uncomfortable relying on assessments they had not completed themselves.

Some people want to start from scratch. Some therapists feel like they want their own story and want to assess this child based on what [they] see, not on what someone else put down.

3.2.5 Ways Information Gained was Used to Promote Child Wellbeing

Use of the CANS by BH Clinicians. The vast majority of responses involved reporting ways that they in fact used the results of the CANS clinically (54) in three different ways: treatment planning (21), clinical decision-making (16), and measuring progress (15).

We have a treatment team meeting once a month that has myself the LDDC care counselor, the administrator, the treatment administrator, the nurse and the schoolteacher. We all meet once a month and when I do the CANS, I always bring the results of that with me to present during treatment meeting. Because that helps us determine where they're at in their program and what milestone they should be placed. So, we use it in that respect, and I have 21 days from the day they come in to do that first comprehensive treatment plan. So, the CANS getting it done prior helps a whole lot in trying to figure out where we're going to go from here.

Our clinicians formulate [the] clinical decision and then it's supported in the results on the CANS. I would say more often than not it supports when the [youth] don't necessarily need ongoing services. It's just sometimes due to the age of the child. How young they are... Finding the right fit for service and helping clinicians determine that or even seeing where we have capacity to serve that age and if not, where to refer them to.

I'll do the CANS and then the therapist, she actually writes the goals and objectives after reviewing them. We’ll choose certain ones to work on for the initial [treatment plan] … Then we review that with the foster parent and the child so that they know exactly what they're working on and why they're working on it. And then we meet as a team once a month to check their goals and see how they're doing on it. So that way when it's time for the next one to be done in three months, we can make adjustments to not only the goals, but also to the CANS assessment if we're ready for that.

CANS Report use by Child Welfare (13). One of the most common themes was that workers reported they were able to access the CANS report in their data management information system.

In one instance recently, there were some questions about past trauma, and I was able to pull the CANS assessment up in [the data management system] and share it on the screen for everyone in the meeting to review it.

In terms of how the information was used, CW workers most commonly indicated they were using it for case planning (13), and in supervision and consultation (9), although nearly as many indicated they did not use this information in supervision or consultation (7).

[At] the monthly consultations, you discuss every case aspect. As far as the screeners and CANS go, the only thing that we really would discuss during consults is if they were due or past due.

At the 6-month case planning conference [having] a checklist [to say] ‘Hey, did you look at the CANS and what did you incorporate?’. When progress is made, I want to show the parents and the kids [by] updating [the case plan]. I [am] fond of [the CANS] now because I actually understand the benefit of them.

I’m an investigator so typically by the time we get the CANS assessment back, we’ve already had monthly consults for the month or it’s time for the case to go to ongoing. I’ll staff with my supervisor [and] once the case transfers to ongoing, I sit down with the ongoing worker, and [discuss] what all happened, the screeners and CANS assessments. That way they have a more accurate picture of what’s going on.

3.3 Suggestions for process change to promote implementation

CW workers offered recommendations that fell into three themes, some of which represented strategies that had already been employed to facilitate the process in their area:

Create a Tickler System for the Screening and Assessment Process (16). The most commonly offered recommendation involved systems for reminding CW workers when these were due. The first quote comes from a liaison.

Each week, we send an email to the workers and supervisors [who] have missing screeners.

A suggestion example came from a CW worker.

A tickler to remind the worker to complete the behavioral health [referral] or the release of information if they screened in for a CANS would be good.

As was noted above BH agency-specific tracking and processing systems were noted as a facilitator for the assessment process.

Modifications to the Timing of When Screeners are Completed (8). Some recommended changing policy in terms of when the screening process must be done.

You may learn something three or four weeks down the road on these kids that you didn’t know initially when these screeners get completed.

Modifications to the Screening Instruments (5). A few responses suggested revising the instruments themselves such as adding open text fields:

I wish some of the Project SAFESPACE screeners had an observation box for us to put what we observed.

Others recommended revision of the items included in the instruments.

I think the [screening instruments] need to have more relatable questions [with topics like] drugs and poverty.

4 Discussion

Results from this late-stage implementation study illustrate the value of examining implementation drift and intervention fidelity several years after a process had been fully implemented and purportedly embedded in day-to-day practice. Implementation studies are more often completed during the installation and early implementation stages of a program [36]. The results of this study suggest that some CW workers and BH clinicians believe that the use of standardized instrumentation does contribute to case and treatment decision-making as has been previously asserted in the literature [2, 40, 52]. However, the current study results also illuminate a need for re-establishment of implementation supports across a number of areas.

Between 2018 and 2022, over half of children in OOHC were screened for trauma or behavioral symptoms. During this same time frame, there was an increase over time in the percent of children who were screened for trauma or behavioral symptoms and met the clinical threshold on one or more screening instruments. However, there was a decrease in percent of children who met clinical threshold on one or more screening instruments and the received a CANS assessment. These findings suggest fidelity to protocol is increasing over time for children who were screened for trauma or behavioral symptoms. In contrast, findings also suggest implementation drift may be occurring for children who met clinical threshold on one or more screening instruments and the received a CANS assessment. Certainly, factors unrelated to implementation may have influenced intervention fidelity such as the impact of COVID-19 on practice behaviors and staff turnover; however, findings such as these suggest the need for a reintroduction of implementation supports. Regarding factors influencing application of screening and assessment results in practice, CW workers use results of screening and assessment in case planning and during supervision and consultation, while BH clinicians incorporate these processes in treatment planning, clinical decision-making, and measuring client progress. However, this was not universally observed across all participants, and barriers were noted such as professional beliefs about standardized instrumentation in clinical decision-making. Ways to improve the use of standardized screening and assessment instrumentation in decision-making include having an internal tracking system or identified staff to manage processes, training on the clinical use of standardized instrumentation, addressing contextual barriers such as use of standardized instruments with some children, and employing a multi-pronged approach in gathering screening and assessment information.

Results demonstrated that for most CW workers and BH clinicians there is understanding regarding the intended purposes of the screening and assessment process. However, it was revealed that some BH clinicians see the purpose of the CANS to be meeting the needs of CW workers and the courts rather than to inform their own clinical decision-making. This finding aligns with a narrative review of treatment decision-making models in behavioral health practice which found that the use of information from standardized decision-support tools is less attractive to some clinicians who favor a more naturalistic approach [50] In addition, there appeared to be baseline understanding of basic components of the practice protocols that are important to facilitating such interagency initiatives [28]. For example, for both screening and assessment it was clear that a substantial portion of BH clinicians understood the importance of gathering the data to complete screening instruments and the CANS from the child, if age appropriate, supplemented by a variety of other sources. However, a subset of clinicians may be relying on shortcuts such as completing the instruments based on the case record or prior records only, rather than in addition to, original data collection.

The initial implementation of the project involved some organizational supports which may not have had the full expected impact. For example, the screening system was set up to enable device-based data entry in real time to avoid duplication of efforts, but many CW workers preferred to print off paper copies and then enter the data into the system subsequently. However, another example demonstrated other support may have a greater than anticipated impact on ongoing implementation, particularly since prior research has indicated that issues associated with information gathering and exchange in such interagency initiatives [26]. The role of the child welfare agency liaison in each region seems to be critical to tracking completion of screeners and facilitating referrals to behavioral health and organizational information exchange. Focus group data revealed the liaisons also play the role of trainer and practice consultant for those in their agency, and a source of important case-related information for BH clinicians.

Implementation studies such as these provide agencies an opportunity to revisit initially established policies and procedures which may benefit from adjustment. A few examples of this were revealed in the current study included revisiting timeframes for completion and reconsidering how much value is truly added by specific instrument modules or scales. While it is not appropriate to rewrite or remove specific instrument or scale items that CW workers see as challenging, support tools or tip sheets could be developed to assist in providing follow up prompts for workers to better explain the purpose of certain items and help children understand what they are being asked.

In an effort to streamline the information coming to very busy CW workers, the intervention protocols were developed to make the amount of information coming to child welfare in the CANS Assessment report very short and to the point. However, CW workers indicated in the first implementation study [54] and in the present study that the information they receive from behavioral health is not detailed enough. The screening system is designed to determine whether a behavioral health assessment is indicated based on whether or not ychildren meet the clinical threshold from a validated screening instrument—removing the requirement for the CW worker to make the decision whether or not to refer on their own. To save effort, CW workers are not asked to provide any sort of narrative regarding their observations during the screening process or detail on what they learned form the child that resulted in the score received. Some CW workers have indicated that they want an open text field to be able to write a narrative as well. Similarly, some BH clinicians reported they are not getting enough detail in the screening report and referral and they may appreciate additional information collected by the CW workers to inform the CANS. This finding is consistent with prior literature suggesting BH clinicians often do not receive sufficient information from child welfare in the referral process to inform their assessment [35] and that CW workers may not understand what information their colleagues really need to support their work [30].

Training needs were also identified. During the transition from the federal grant period multiple days of training were provided between initial implementation and full implementation at which time multiple training days were no longer feasible. After full implementation raining was reduced to a small part of new CW worker trainings about the forms that are required when children enter OOHC. It is little wonder that some CW workers see the CANS as a paperwork function rather than a valuable clinical tool. For both CW workers and BH clinicians there appears to be a need for ongoing advanced training to keep workers aligned with how to use the information from these tools in a way that meaningfully supports case and treatment decision-making. In addition, some CW workers indicated the results of screening and assessment are not used in supervision and consultation which, along with training, can be an important tool for reinforcing practice [22]. Focus groups revealed suggestions for process improvements that seem to be related to fidelity to intervention protocols in some agencies. Agency-specific tracking and facilitation processes were developed in some agencies to ensure that screening and assessment practices are being completed on time and information is exchanged according to interagency protocols. Implementation supports could work to spread these strategies to other agencies and promote interagency collaboration on successful initiatives that improve compliance. Similar protocols could be developed to support high quality use of the data from these processes in treatment and case decision-making as intended.

The current study provides an exemplar of the wealth of information that can be gained from conducting implementation studies routinely after practices have reached full implementation. However, one of the themes that arose from both CW workers and BH clinicians was that some practitioners fail to appreciate the value of standardized decision-support tools such as the screeners and CANs to meet the behavioral health needs of the children for whom they are responsible. Of note, the lack of appreciation for standardized decision-support tools was also identified in this project’s implementation study conducted at the end of the federal grant period [54]. Sadly, this finding persists and seems to be much harder to address than the other actionable areas revealed from the study and highlights the need for education in both child welfare and behavioral health to be able to integrate standardized tools and practice experience in their decision-making processes. What do you do to address that, particularly in fields like child welfare where turnover and workload seem to be perpetual concerns.

4.1 Limitations

The current study focuses on statewide implementation of interagency interventions in one state, so the results cannot be assumed to be generalizable in other settings. Many of the areas in need of additional implementation supports are likely due to circumstances and weaknesses in this particular state context. Data were collected from a convenience sample of child welfare and behavioral health staff; therefore, it cannot be assumed the findings are representative of all employees within these organizations. Moreover, other factors such as time related to workload and other internal and external pressures may have influenced responses to focus group prompts. Though strategies of rigor were applied when analyzing focus group data, the research team did not conduct member checking to validate themes. The focus group findings were also limited by challenges associated with how some of the focus groups were conducted, as inadequate attention was paid to some questions and a lack of follow up prompts in some groups meant that the depth of response to some questions was limited, likely due to lack of extensive understanding of the practices, which resulted in missed opportunities to better understand CW worker and BH clinician perceptions. Were the research team to have conducted the focus groups personally this may have been avoided. Descriptive findings were reported using administrative data. A more robust analysis would allow researchers to answer in full questions of fidelity to screening and assessment practices.

5 Conclusion

In these complex fields, organizations struggle with strategies for promoting evidence-informed decision-making internally and collaboratively with other agencies. While results of this study are encouraging regarding one state’s implementation of a complex practice initiative, use of these data as intended remains a challenge in some areas despite having embedded standardized decision support for over a decade. Prior research has suggested that it can take a very long time for the outcomes of interagency initiatives to be realized, so efforts to promote implementation must be sustained [25]. The results of this study have implications for organizations seeking to reinforce data-informed practices in terms of strategies for addressing barriers on the worker and the agency level. Additional research is needed regarding how managers can establish infrastructure and cultural supports to promote the use of data to inform practice decisions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

References

Ai AL, Foster LJJ, Pecora PJ, Delaney N, Rodriguez W. Reshaping child welfare’s response to trauma. Res Soc Work Pract. 2013;23(6):651–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731513491835.

Akin BA, Strolin-Goltzman J, Collins-Camargo C. Successes and challenges in developing trauma-informed child welfare systems: a real-world case study of exploration and initial implementation. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;82:42–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.007.

Andershed A, Andershed H. Improving evidence-based social work practice with youths exhibiting conduct problems through structured assessment. Eur J Soc Work. 2016;19(6):887–900.

Bai Y, Wells R, Hillemeier MM. Coordination between child welfare agencies and mental health service providers, children’s service use, and outcomes. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(6):372–81.

Barth RP, Rozeff LJ, Kerns SEU, Baldwin MJ. Partnering for Success: Implementing a cross-systems collaborative model between behavioral health and child welfare. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;117:1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104663.

Bartlett JD, Barto B, Griffin JL, Fraser JG, Hodgdon H, Bodian R. Trauma informed care in the Massachusetts child trauma project. Child Maltreat. 2016;21(2):101–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559515615700.

Blase KA, Fixsen DL. Core Intervention Components: Identifying and Operationalizing What Makes Programs Work. ASPE Research Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Human Services Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. 2013.

Blase KA, Van Dyke M, Fixsen DL, Bailey FW. Implementation science: Key concepts, themes, and evidence for practitioners in educational psychology. In: Kelly B, Perkins D, editors. Handbook of implementation science for psychology in education: how to promote evidence based practice. London: Cambridge University Press; 2012.

Boel-Studt SM, Flynn HA, Deichen Hansen ME, Panisch LS. Enhancing behavioral health services for child welfare-involved parents: a qualitative study. J Pub Child Welf. 2022;16(5):607–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2021.1942389.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Bunger AC, Cao Y, Girth AM, Hoffman J, Robertson HA. Constraints and benefits of child welfare contracts with behavioral health providers: conditions that shape service access. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2016;43(5):728–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0686-1.

Casaneuva C, Ringeisen H, Wilson E, Smith K, Dolan M. NSCAW II baseline report: Child well-being. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. 2011.

Chinitz S, Guzman H, Amstutz E, Kokchi J, Alkon M. Improving outcomes for babies and toddlers in child welfare: a model for infant mental health intervention and collaboration. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;70:190–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.05.015.

Conradi L, Wherry J, Kisiel C. Linking child welfare and mental health using trauma-informed screening and assessment practices. Child Welfare. 2011;90:129.

Cooper JL, Vick J. Promoting social-emotional wellbeing in early intervention services: a fifty-state view. New York: National Center for Children in Poverty, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University; 2009.

Crandal BR, Martin JK, Hazen AL, Rolls Reutz JA. Measuring collaboration across children’s behavioral health and child welfare systems. Psychol Serv. 2019;16:111–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000302.

Darlington Y, Feeney JA. Collaboration between mental health and child protection services: professionals’ perceptions of best practice. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2008;30(2):187–98.

Dhalla S, Zumbo BD, Poole G. A review of the psychometric properties of the CRAFFT instrument: 1999–2010. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(1):57–64.

Foa EB, Johnson KM, Feeny NC, Treadwell KRH. The child PTSD symptom scale: a preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2001;30(3):376–84. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3003_9.

Garcia AR, Circo E, DeNard C, Hernandez N. Barriers and facilitators to delivering effective mental health practice strategies for youth and families served by the child welfare system. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;52:110–22.

Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1997. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x.

Gopalan G, Kerns SEU, Horen MJ, Lowe J. Partnering for success: factors impacting implementation of a cross-systems collaborative model between behavioral health and child welfare. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2021;48:839–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01135-5.

Griffin G, McClelland G, Holzberg M, Stolbach B, Maj N, Kisiel C. Addressing the impact of trauma before diagnosing mental illness in child welfare. Child Welfare. 2011;90(6):69.

Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011.

Hanson RF, Schoewald S, Saunders BE, Chapman J, Palinkas LA, Moreland AD, Dopp A. Testing the community-based learning collaborative (CBLC) implemental model: a study protocol. Int J Ment Heal Syst. 2016;10:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0084-4.

Humphries S, Stafinski T, Mumtaz Z, Menon D. Barriers and facilitators to evidence-use in program management: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:171.

Hurlburt MS, Leslie LK, Landsverk J, Barth RP, Burns BJ, Gibbons RD, Slymen DJ, Zhang JJ. Contextual predictors of mental health service use among children open to child welfare. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(12):1217–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1217.

Hwang SHJ, Mollen CJ, Kellom KS, Dougherty SL, Noonan KG. Information sharing between the child welfare and behavioral health systems: perspectives from four stakeholder groups. Soc Work Ment Health. 2017;15(5):500–23.

Jankowski MK, Schifferdecker KE, Butcher RL, Foster-Johnson L, Barnett ER. Effectiveness of a trauma-informed care initiative in a state child welfare system: a randomized study. Child Maltreat. 2019;24(1):86–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559518796336.

Kerns SEU, Pullmann MD, Putnam B, Buher A, Holland S, Berliner L, Trupin EW. Child welfare and mental health: facilitators of and barriers to connecting children and youths in out-of-home care with effective mental health treatment. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;46:315–24.

Kisiel C, Fehrenbach T, Small L, Lyons JS. Assessment of complex trauma exposure, responses, and service needs among children and adolescents in child welfare. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2009;2:143–60.

Ko SJ, Ford JD, Kassam-Adams N, Berkowitz SJ, Wilson C, Wong M, Layne CM. Creating trauma-informed systems: child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2008;39(4):396–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.39.4.396.

Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Haynes SN, Owens JA, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(2):210–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.210.

Lang JM, Ake G, Barto B, Caringi J, Little C, Baldwin MJ, Stewart CJ. Trauma screening in child welfare: lessons learned from five states. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2017;10(4):405–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0155-y.

McMahon RJ, Forehand RL. Helping the noncompliant child, 2nd edition: family-based treatment for oppositional behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005.

Metz A, Bartley L. Active implementation frameworks for program success: how to use implementation science to improve outcomes for children. Zero to Three. 2012;32:11–8.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.; 1994.

Moullin JC, Sabater-Hernández D, Fernandez-Llimos F, Benrimoj SI. A systematic review of implementation frameworks of innovations in healthcare and resulting generic implementation framework. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-015-0005-z.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0.

Ponniah K, Weissman MM, Bledsoe SE, Verdeli H, Gameroff MJ, Mufson L, Wickramaratne P. Training in structured diagnostic assessment using the DSM-IV criteria. Res Soc Work Pract. 2011;21(4):452–7.

Praed Foundation. Child and adolescent needs and strengths [Standard CANS Comprehensive]. 2016 Reference Guide, Chicago, IL: Chaplin Hill. 2016.

Romanelli LH, Landsverk J, Levitt JM, Leslie LK, Hurley MM, Bellonci C, Jensen PS. Best practices for mental health in child welfare: screening, assessment, and treatment guidelines. Child Welf. 2009;88(1):163–88.

Sedlak A, Schultz D, Wells S, Lyons P, Doueck H, Gragg F. Child protection and justice systems processing of serious child abuse and neglect cases. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:657–77.

Spehr MK, Zeno R, Warren B, Lush P, Masciola R. Social-emotional screening protocol implementation: a trauma-informed response for young children in child welfare. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33:675–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2019.05.003.

Sullivan AD, Breslend NL, Strolin-Goltzman J, Bielawski-Branch A, Jorgenson J, Deaver AH, Forehand G, Forehand R. Feasibility investigation: leveraging smartphone technology in a trauma and behavior management-informed training for foster caregivers. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;101:363–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.03.051.

Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748.

Timonen-Kallo E, Hamalainen J, Laukkanen E. Interprofessional collaboration in finish residential care: challenges in incorporating and sharing expertise between the child protection and health care systems. Child Care Pract. 2017;23(4):389–403.

Tullberg E, Kerker B, Muradwij N, Saxe G. The Atlas project: integrating trauma-informed practice into child welfare and mental health settings. Child Welfare. 2017;95:107–25.

van den Steene H, van West D, Peeraer G, Glazemakers I. Professionals’ views on the development process of a structural collaboration between child and adolescent psychiatry and child welfare: an exploration through the lens of the life cycle model. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2018;37:1539–49. https://doi.org/10.10007/s00787-018-1147-7.

Verbist AN, Winters AM, Antle BA, Collins-Camargo C. A review of treatment decision-making models and factors in mental health practice. Fam Soc J Contemp Soc Sci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044389420921069.

Wandersman A, Alia K, Cook BS, Hsu LL, Ramaswamy R. Evidence-based interventions are necessary but not sufficient for achieving outcomes in each setting in a complex world. Am J Eval. 2016;37:544–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214016660613.

Whitt-Woosley A. Trauma screening and assessment outcomes in child welfare: a systematic review. J Publ Child Welf. 2020;14(4):412–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2019.1623965.

Whitt-Woosley A, Sprang G, Royse DG. Identifying the trauma recovery needs of maltreated children: examination of child welfare workers’ effectiveness in screening for traumatic stress. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;81:296–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.05.009.

Winters A, Collins-Camargo C, Antle B. Implementing trauma-responsive screening and assessment: lessons learned from a statewide demonstration study in child welfare. Prof Dev Int J Contin Soc Work Educ. 2021;24(1):15–28.

Winters AM, Collins-Camargo C, Antle BF, Verbist AN. Implementation of system-wide change in child welfare and behavioral health: the role of capacity, collaboration, and readiness for change. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104580.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMW, CCC, LU conducted qualitative analysis. AMW and CCC wrote findings for manuscript. AMW conducted quantitative analysis and wrote findings for manuscript. CCC wrote introduction. AMW, CCC, LU, and LM wrote discussion and conclusion. All authors reviewed manuscript prior to submission. AMW corresponding author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Winters, A.M., Collins-Camargo, C., Utterback, L. et al. Use of standardized decision support instruments to inform child welfare decision-making: lessons from an implementation study. Discov Psychol 4, 76 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00182-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00182-x