Abstract

Within a year of its launch, ChatGPT has seen a surge in popularity. While many are drawn to its effectiveness and user-friendly interface, ChatGPT also introduces moral concerns, such as the temptation to present generated text as one’s own. This led us to theorize that personality traits such as Machiavellianism and sensation-seeking may be predictive of ChatGPT usage. We launched two online questionnaires with 2000 respondents each, in September 2023 and March 2024, respectively. In Questionnaire 1, 22% of respondents were students, and 54% were full-time employees; 32% indicated they used ChatGPT at least weekly. Analysis of our ChatGPT Acceptance Scale revealed two factors, Effectiveness and Concerns, which correlated positively and negatively, respectively, with ChatGPT use frequency. A specific aspect of Machiavellianism (manipulation tactics) was found to predict ChatGPT usage. Questionnaire 2 was a replication of Questionnaire 1, with 21% students and 54% full-time employees, of which 43% indicated using ChatGPT weekly. In Questionnaire 2, more extensive personality scales were used. We found a moderate correlation between Machiavellianism and ChatGPT usage (r = 0.22) and with an opportunistic attitude towards undisclosed use (r = 0.30), relationships that largely remained intact after controlling for gender, age, education level, and the respondents’ country. We conclude that covert use of ChatGPT is associated with darker personality traits, something that requires further attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

ChatGPT was launched in late November 2022 and has seen an enormous increase in popularity, amassing over 100 million users within a matter of months [41]. Key factors that explain the popularity of ChatGPT are the quality of its outputs and its user-friendly interface [68, 73, 74].

ChatGPT receives positive appraisal from its users. In Hungary, 86% of high school students had used ChatGPT daily or several times per week, with 69% agreeing that ChatGPT improved their understanding of complex concepts [28]. An analysis of tweets about ChatGPT revealed positive sentiments, especially regarding creative and entertainment tasks, language processing, and software development, with only a few tweets expressing concerns about misuse [84]. Choudhury and Shamszare [15] reported that ChatGPT is mostly used for information retrieval and entertainment, and showed a link between trust, intention to use, and actual use. More generally, Brauner et al. [7] evaluated the perceived impact of AI on society, with respondents viewing AI as unlikely to threaten their personal careers, and likely to drive economic growth.

At the same time, several concerns about ChatGPT have been reported. These include fears of work disruptions and the prospect of generative AI surpassing human intelligence (e.g., [30, 50, 65, 70]). These concerns are not unique to ChatGPT but correspond with general literature on AI fears. For example, using their General Attitudes towards AI Scale (GAAIS), Schepman and Rodway [72] found positive views on AI in big data applications but negative views when AI is used for judgment tasks, such as counseling or selecting staff for employment. Kieslich et al. [48] introduced a Threats of AI questionnaire and applied it in three fictitious scenarios: medical treatment, recruitment, and creditworthiness assessments. Wang and Wang [89] and Li and Huang [54] identified various AI-related anxieties, including privacy, bias, job replacement, existential risks, and transparency, and showed that these anxieties were all positively correlated, reflecting a broader fear of AI. Sindermann et al. [75] introduced a short questionnaire to assess an Attitudes Toward AI (ATAI) scale and revealed two negatively correlated components: acceptance of AI (trust, benefit humankind) and fear of AI (fear, destroy humankind, cause job losses). This corresponds with the economic perspectives on AI, which state that AI can both augment jobs and replace jobs [83].

Apart from general AI anxiety, the undisclosed use among students and professionals raises various moral tensions [24, 58, 61, 66]. Fears of falsely accusing others of plagiarism and fears of being accused of using ChatGPT have been reported among teachers and students [11, 12, 33, 71]. Ibrahim et al. [42] and Chan and Lee [14] reported conflicts between optimistic attitudes among students and concerns about ChatGPT among teachers. Additionally, concerns exist over how ChatGPT collects personal data [35, 38, 91]. In summary, the advantages of ChatGPT are countered by moral dilemmas, with non-use or denial of use motivated by cheating concerns, exposure risks, or concerns about OpenAI’s ethics [10, 71].

The aforementioned moral dilemmas led us to postulate that ChatGPT usage may be predictable based on personality traits. Understanding how personality traits relate to (covert) AI use is relevant because it can unveil latent psychological drives and inform the development of ethically guided technology policies. We posit that the tension that may exist between the recipients/readers of texts (such as the implicit expectation that ChatGPT usage must be disclosed) and the motivations of the sender/creator of texts (such as the wish to get work done effectively) is something that needs attention and must be exposed. We speculated that individuals who are more prone to sensation-seeking or have lower internal inhibitions, as well as those who exhibit dark traits similar to Machiavellianism, might be more inclined to use ChatGPT as they see it as a tool for covertly obtaining an edge in their study or work environments. We also expected that individuals with stronger neurotic tendencies may shy away from ChatGPT, being concerned about the potential consequences and moral implications of its use.

Various studies have previously linked personality traits to technology acceptance. Higher openness was found to be predictive of the use of video conferencing, while neuroticism corresponded with reduced performance expectations [52]. In another study, extraversion and agreeableness correlated with the intent to use new software [81]. Kaya et al. [47] found that those with higher openness exhibited a more positive attitude towards AI, while a more positive personality across all BFI items was associated with more forgiving attitudes towards the negative aspects of AI. In the U.S., fears about AI, such as cyber-terrorism and job replacement, were found to be associated with unemployment and other anxieties [59]. Also, exposure to science fiction media has been linked to fear of robots and AI, along with fears of loneliness and unemployment [55]. Additionally, narcissism was associated with seeing technology as useful in the workplace, potentially as a means to achieve personal goals or status [3].

In summary, while research exists that links personality traits to technology acceptance, the outcomes are diverse and not specifically concerned with ChatGPT. One exception is Li [53], who linked intellectual humility with positive attitudes towards ChatGPT; the author suggested that humility might influence openness to new experiences like using ChatGPT. Moreover, a questionnaire study among 283 students by Greitemeyer and Kastenmüller [34], conducted in February 2023 at a university in Austria, showed that narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy were positively correlated with the intention to use chatbot-generated texts for academic cheating. The trait conscientiousness, and especially honesty-humility, showed a negative correlation with the intention to use.

To gain deeper insights into the relationship between ChatGPT usage, ChatGPT acceptance, and personality, we administered a questionnaire to 2000 respondents. The questionnaire measured the frequency of ChatGPT usage and included a ChatGPT Acceptance Scale. In a broad sense, this encompassed a positive dimension of utility and trust in the tool, as well as a dimension of concern, in line with the attitude towards AI scale by Sindermann et al. [75]. Additionally, our questionnaire included 17 items that measured personality traits and included scales to ascertain the extent of the respondents’ beliefs in machine capabilities and propensity to trust machines in general. The addition of trust as a predictor is important because trust in technology is seen as a key factor in predicting the extent of its use, including whether it is underutilized or overrelied upon [25, 39, 62, 64]. In a follow-up questionnaire conducted six months later, again with 2000 respondents, we aimed to replicate the findings with more elaborate personality items, including a 9-item Machiavellianism scale and a 44-item Big Five Inventory (BFI).

2 Questionnaire 1 (September 2023)

2.1 Methods

The questionnaire was implemented using Qualtrics [67]. It was entitled “Acceptance of ChatGPT”, and its aim was described as follows: “to investigate how people feel about ChatGPT and technology in general. You will be asked to complete a questionnaire with your views on ChatGPT, technology, and the capabilities of humans and machines. You will also answer several questions regarding your personality.” The respondents were informed that the questionnaire would take approximately 12 min of their time.

The questionnaire contained various general items, specifically: age (G1), gender (G2), education level (G3), and current occupation (G4). The respondents were also asked about whether they had heard of ChatGPT (G5), and how often (G6) and for what types of tasks (G7, G8) they use it. Furthermore, they were asked to indicate several specifics of their use and experience, such as whether they used the paid version (G9), whether they used plugins (G10), what they think are strengths and weaknesses of ChatGPT (G11), and how frequently they use competing models such as Google’s Bard (G12). G8 and G11 were free-response items.

Additionally, the questionnaire included a custom 22-item ChatGPT Acceptance Scale (Table 1), consisting of five-point items (Strongly disagree to Strongly agree). The 22 statements were presented in a random order per respondent. The corresponding introduction was as follows: “Please indicate your level of agreement with each statement about your experience with ChatGPT without its beta features. If you have no experience with ChatGPT, please provide an estimate based on how you think you would experience ChatGPT if you were to use it.”

The 22 items were constructed based on the premise that the popularity of ChatGPT can be attributed to perceived usefulness and satisfaction (CA1–13) [85], mirroring technology acceptance research [17, 87]. For CA1–5, the same topics were maintained as the response options in a previous item about ChatGPT usage (G7). Furthermore, reinforced by media attention regarding the dangers of AI [70] and privacy violations [38], we postulated that the use of ChatGPT might be adversely affected by concerns among individuals. These concerns could pertain to the misuse of data by OpenAI (CA15) or the apprehension of being identified as a user of ChatGPT (CA16), for which detectors might offer a solution (CA18). Concerns could also resonate at a broader societal level (CA17, CA21), leading respondents to have the opinion that the use of ChatGPT should be curtailed in schools (CA20) or altogether (CA22).

Additionally, respondents indicated whether they believed that humans surpass machines or whether machines surpass humans for 11 statements (F1–11; based on [21, 27]). Furthermore, our questionnaire included a Propensity to Trust Machines scale [60], consisting of six items, answered on a scale of Strongly disagree to Strongly agree (T1–6) (see Supplementary Material). Composite scores were computed for both scales by standardizing the item scores, and then averaging across the items.

Finally, respondents were asked about their level of agreement with respect to 17 personality-related statements (P1–17, see Table 2). The statements were introduced as “I see myself as someone who …” (as in [69]), from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree. The 17 items were presented in a random order per respondent.

-

P1 and P2 were taken from a 9-item Machiavellianism scale from the Short Dark Triad (SD3, [45]). These two items were selected because they described the individual’s own behavior, in contrast to the other items, which pertained to a Machiavellian’s interaction with others.

-

P3–5 were taken from the short form of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-15) presented by Spinella [77]. The items were selected because they loaded highly on the three factors, i.e., motor impulsivity, non-planning impulsivity, and action impulsivity.

-

P6 and P7 were part of the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS, [40]). These two items were selected because they were previously found to have the highest item-total correlations [86].

-

Finally, the 10-item short Big Five Inventory (BFI-10) from Rammstedt and John [69] was included (P8–17).

Respondents were required to respond to all questions. They were allowed to navigate back and forth in the questionnaire and edit their responses. On the final page, respondents were thanked for their participation and redirected to Prolific to receive their remuneration: “Thank you for taking part in this study. Please click the button below to be directed back to Prolific and register your submission.”

Respondents enrolled in the study through the Prolific platform (https://www.prolific.co). No pre-screening criteria were applied. They were provided with a hyperlink to Qualtrics to complete the questionnaire. A total of 2000 respondents completed the questionnaire on 11 September 2023, between 15:30 and 17:50 Central European Time. For items G1, G2, G4–12, CA1–21, and F1–11, results from 51 additional respondents were available from a pilot test conducted a day earlier. Each respondent received a remuneration of £1.80.

To uncover the latent structure of the ChatGPT Acceptance Scale, we applied maximum likelihood factor analysis. Because factors were correlated, oblique rotation was used [26], in the form of a Promax rotation [37]. Factor scores were calculated using the Thomson regression method [4]. The relationships between ChatGPT usage, ChatGPT Acceptance factor scores, personality items, and age, gender, and education level were described using Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients.

We follow the guidelines of Gignac and Szodorai [31], where correlations of 0.10, 0.20, and 0.30 are characterized as weak, moderate, and strong, respectively. Note that with a sample size of 1980, a correlation of 0.074 is statistically significantly different from 0 (p < 0.001). Regarding the relationships between ChatGPT usage and personality items, partial correlations were calculated as well, controlling for age, gender, education level, and nationality (defined as a respondent × country matrix with 0s and 1s indicating membership of the country).

2.2 Results

Of the 2051 respondents, 76 responded “No” to the question “Have you ever heard of ChatGPT?” (G5) and were excluded, leaving a sample of 1975 respondents for further analysis. The 1975 respondents took, on average, 12.2 min to complete the questionnaire (SD: 6.9 min, median: 10.4 min). The respondents resided in 34 different countries. The country for 5 respondents was unknown. The five most highly represented countries were South Africa (n = 517), the UK (n = 409), Portugal (n = 259), Poland (n = 216), and Italy (n = 115).

The responses to the general questions are shown in Table 3. The mean age of respondents was 32.0 years (SD: 10.8) (G1), and the sample comprised nearly equal numbers of males and females (G2). The majority of respondents (53.6%) reported being in full-time employment; 22.1% identified as students (G4).

Frequency of ChatGPT usage was moderate, with 954 out of the 1975 respondents (48.3%) indicating they used ChatGPT at least once every two weeks (G6). The respondents used ChatGPT for a range of tasks, primarily answering questions, but also for text processing and generating content. The use of ChatGPT for calculations was rare (10.1%), consistent with its lesser proficiency in such tasks [9]. A mere 4.4% of the respondents reported using the paid version (ChatGPT-4) (G9). The use of alternative chatbots, such as those from Microsoft and Google, was not pronounced either: 63.4% of the respondents indicated that they never use similar models (G12).

For the question “Describe what you use ChatGPT for in a number of sentences” (G8), respondents indicated using ChatGPT for a variety of purposes, including generating creative content, academic assistance, professional writing, coding help, language learning, entertainment, research, task automation, business strategy, and personal uses like meal planning. Regarding the question “What are the strengths and weaknesses of ChatGPT?” (G11), the reported strengths included its efficiency in text generation, versatility, ease of use, and 24/7 availability. Its weaknesses included occasional inaccuracies, lack of up-to-date information, and concerns about data privacy and over-reliance, which may impact human creativity and critical thinking. The Supplementary Material provides a more detailed account of the responses to G8 and G11.

Table 4 shows the means and standard deviations for the items of the ChatGPT Acceptance Scale. Respondents found ChatGPT to be user-friendly (CA10–13) and beneficial for generating and reviewing text (CA1–4, CA8), but less adequate for calculations (CA5). Respondents believed that ChatGPT should not be prohibited (CA22) and regarded it as a positive development for society (CA21). However, respondents did express that misuse in school settings should be prevented (CA20). Concerns about misuse or potential repercussions from using the tool were not particularly high (CA15–17), and respondents expressed a desire for the existence of a ChatGPT detector (CA18).

The first five eigenvalues of the 22 × 22 correlation matrix of the ChatGPT Acceptance Scale were 7.50, 1.82, 1.39, 1.15, and 0.87. Based on these eigenvalues, and our interpretation of the factor loadings, it was decided to extract two factors. The rotated factor loadings are shown in Table 4. Interpretation of these loadings led us to describe Factor 1 as ‘Effectiveness’ and Factor 2 as ‘Concerns’. The scores of the two factors showed a negative intercorrelation, at r = − 0.34.

Table 5 shows the correlation coefficients among age (G1), gender (G2), education (G3), ChatGPT usage (G6), the ChatGPT factor scores (CA1–22), Machines Surpass Humans scores (F1–11) and Propensity to Trust Machines scores (T1–6).

Table 5 indicates the following:

-

Older respondents were less inclined to use ChatGPT (G1 vs. G6: r = − 0.21).

-

Older respondents attributed lower effectiveness and expressed more concerns about ChatGPT (r = − 0.26, r = 0.12).

-

Males were slightly more frequent users than females (G2 vs. G6: r = 0.13).

-

Males had fewer concerns about ChatGPT than females (r = 0.11).

-

Correlations with educational level were generally weak, |r|< 0.10, with more highly educated respondents reporting higher use (G3 vs. G6: r = 0.07).

-

The use of ChatGPT (G6) was moderately associated with Propensity to Trust Machines (r = 0.22)

-

The use of ChatGPT (G6) was strongly associated with ChatGPT Effectiveness (r = 0.57) and ChatGPT Concerns (r = − 0.36).

With regard to personality, it was decided to present correlations with all 17 individual personality items due to the diversity of personality traits. The correlation coefficients, as shown in Table 6, are at their highest, only moderate. Use of ChatGPT (G6) seemed to be explainable by:

-

Machiavellianism: Manipulation tactics (P1: r = 0.18),

-

Low non-planning impulsivity, i.e., planning for the future (P4: r = 0.14),

-

Sensation seeking tendencies (P6, P7: r = 0.12, r = 0.10), and

-

Low neuroticism, manifested as being relaxed (P11: r = 0.11) or low nervousness (P16: r = − 0.08).

Our sample includes different national backgrounds, which risks aggregation bias, meaning that the obtained correlations could be due to group differences rather than individual differences within groups. To illustrate, respondents from the UK had a higher mean age (39.9 years, n = 409) compared to those from South Africa (29.0 years, n = 517), but the former group was also less positive about ChatGPT’s Effectiveness, scoring nearly a full standard deviation lower (-0.51 for UK vs. 0.41 for South Africa). Another issue is that of confounding. For example, although sensation seeking (P6, P7) was predictive of ChatGPT usage (r = 0.12, r = 0.10), younger age, which involves with higher sensation seeking (r = − 0.17, r = − 0.17), was also predictive of ChatGPT usage (G1 vs. G6: r = − 0.21).

We computed partial correlations to isolate the influence of personality traits on ChatGPT usage from respondents’ age, gender, education, and country. The partial correlations, as shown in parentheses in the rightmost column of Table 6, were generally smaller compared to the raw correlations. Only two partial correlations were stronger than 0.10, namely Machiavellianism: Manipulation tactics (P1: rp = 0.12) and low non-planning impulsivity, i.e., planning for the future (P4: rp = 0.10).

3 Questionnaire 2 (March 2024)

3.1 Methods

Questionnaire 1 has a number of limitations, namely: (1) the ChatGPT Acceptance Scale contained several items with low loadings (see Table 4), offering potential for creating an improved and shortened scale, (2) personality was measured with only a few items, which may limit reliability and validity, and (3) our hypotheses pertained to the covert and opportunistic use of ChatGPT, but this aspect of ChatGPT usage was not inquired about.

To address these limitations, Questionnaire 1 was repeated with the same recruitment criteria, but (1) with a shorter version of the ChatGPT Acceptance Scale, retaining items with high loadings (CA3, 8, 12, 15, 17, 22), (2) with a 44-item BFI instead of a 10-item version (BFI-44; [44]), and with all 9 items of the Machiavellianism scale of the Short Dark Triad [45], and (3) by including three custom items regarding the opportunistic use of ChatGPT, namely:

O1. I would consider using ChatGPT for tasks, assignments, or other obligations without disclosure if I believed it could significantly improve my output or efficiency.

O2. I have used ChatGPT to assist with tasks, assignments, or other obligations and did not disclose its use.

O3. Using ChatGPT for completing tasks or assignments in academic or professional settings without disclosure is acceptable.

The 9 items (CA3, 8, 12, 15, 17, 22, and O1 to O3) were presented in a random order per respondent.

Questionnaire 2 also included a commonly used item about loneliness (e.g., [32]), as we speculated that loneliness could be a predictor for the frequency with which one interacts with conversational AI tools such as ChatGPT. The specific question was: “How often do you feel lonely?”, to which respondents could respond 1 (Often/always), 2 (Some of the time), 3 (Occasionally), 4 (Hardly ever), or 5 (Never). This was reverse coded, so higher scores represent higher levels of loneliness. Furthermore, a test question was included: “What is 6 × 19?”, to verify whether respondents were attentive when filling out the questionnaire.

A total of 2001 respondents completed the questionnaire on 20 March 2024, between 16:19 and 18:40 Central European Time. Scores for Machiavellianism and for the five personality dimensions of the BFI-44 were determined by calculating the mean over the items (9 items for Machiavellianism, 10 for Openness, 9 for Conscientiousness, 8 for Extraversion, 9 for Agreeableness, and 8 for Neuroticism). For the short ChatGPT Acceptance Scale, factor scores were calculated as in Questionnaire 1. For opportunism, a factor score was calculated after extracting one factor from the three items.

3.2 Results

Of the 2001 respondents, 20 responded “No” to the question “Have you ever heard of ChatGPT?” (G5) and were excluded, leaving 1981 respondents for further analysis. The 1981 respondents took an average of 10.3 min to complete the questionnaire (SD: 6.8 min, median: 8.5 min). They resided in 33 different countries; the country for 2 respondents was unknown. The five most highly represented countries were South Africa (n = 441), the UK (n = 315), Portugal (n = 238), Poland (n = 186), and Italy (n = 112). In total, 208 out of 1981 respondents in Questionnaire 2 had also participated in Questionnaire 1.

Regarding the test question: “What is 6 × 19”, 1903 out of 1981 respondents (96.1%) gave the correct answer of 114, while 27 respondents answered 144, and 10 answered 104. Since a large portion of the respondents correctly answered the question (or attempted to do so), it was decided not to exclude any respondents. An advantage of this is that a comparison between Questionnaire 1 and Questionnaire 2 is reasonably possible.

Table 3 provides an overview of the demographics of the respondents of Questionnaire 2. The distribution of age (G1), gender (G2), education level (G3), and current occupation (G4) is highly similar between Questionnaire 1 and 2. However, the reported use of ChatGPT is different, with 13.0% using ChatGPT more than 4 days a week in Questionnaire 1 versus 21.3% doing so in Questionnaire 2 (G6). Usage saw increases across all categories (Q7), except for use for enjoyment. There was also an increase in paid use, from 4.4% in Questionnaire 1 to 7.7% in Questionnaire 2 (Q9).

Table 7 shows the results for the short ChatGPT Acceptance Scale. Respondents found ChatGPT useful for getting work done (CA3) and for accomplishing tasks (CA8). On the scale of 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree), the mean response for CA8 in particular was higher in Questionnaire 2 (3.85) compared to Questionnaire 1 (3.58). Respondents were not overly concerned about data misuse (CA15) and were not of the opinion that ChatGPT should be banned (CA22).

Table 8 shows the results for ChatGPT Opportunism. Respondents were, on average, in moderate agreement with the statement that they would consider using ChatGPT for tasks without reporting this use (O1). Respondents also admitted to having already engaged in such use, with a mean score around the midpoint between Strongly disagree and Strongly agree (O2). However, respondents did not find such behavior acceptable, on average (O3).

Correlations between key variables, shown in Table 9, indicate that ChatGPT usage (G6) was negatively associated with age (G1: r = − 0.22), positively associated with ChatGPT Effectiveness (r = 0.59), and negatively with ChatGPT Concerns (r = − 0.31). Males were slightly more frequent users than females (G2 vs. G6: r = 0.10). These correlations are consistent with Questionnaire 1 (r = − 0.21, 0.57, and − 0.36, respectively). An opportunistic attitude towards ChatGPT (O1–3) was negatively associated with ChatGPT Concerns (r = − 0.29) and positively with ChatGPT Effectiveness (r = 0.57). Moreover, older respondents had a lower ChatGPT Opportunism score (r = − 0.21).

Table 10 shows the correlation coefficients between personality dimensions and loneliness versus ChatGPT usage (G6). ChatGPT usage was particularly associated with Machiavellianism (r = 0.22) and openness (r = 0.18), and negatively with neuroticism (r = − 0.09). Machiavellianism showed a moderate to strong correlation with an opportunistic attitude towards ChatGPT (r = 0.30), also after controlling for age, gender, education level, and the country of the respondent (rp = 0.25).

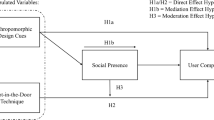

Figure 1 provides an overview of the associations between ChatGPT usage (G6) and age (G1), the Propensity to Trust Machines score (T1–6), Machiavellianism, and the two ChatGPT Acceptance Scale factor scores: Effectiveness and Concerns.

Means and surrounding 95% confidence intervals of self-reported ChatGPT usage (G6, where 1: Never, 2: Less than once a month, 3: About once a month, 4: About once every 2 weeks, 5: 1–3 days a week, 6: 4–6 days a week, 7: Every day) as a function of scores on eight variables from Questionnaire 1 (in black) and Questionnaire 2 (in blue). In each subfigure, the entire sample of respondents was divided into five subgroups. The numbers in gray are the sample sizes for the five subgroups

4 Discussion

Following its release to the public in late 2022, ChatGPT has enjoyed a favorable reception [51, 76]. The worldwide popularity of ChatGPT is undeniable, not only among students (e.g., [42, 43, 88]) but also among academics [6, 80], software engineers [1], communication instructors [12], and other individuals who process text or code as part of their jobs [8, 13, 23]. Our results showed that ChatGPT was reasonably popular among our respondents as well, with 32% and 43% using it on a weekly basis in September 2023 and March 2024, respectively. The majority of respondents used the free version, with the use of the paid versions being relatively rare, although increasing from 4.4% to 7.7% within half a year. This trend may be driven by the fact that ChatGPT-4 delivers higher-quality output than ChatGPT-3.5 [9, 19, 63].

Although ChatGPT offers benefits, there exists a moral tension wherein some have labeled the use of ChatGPT as a form of cheating [82] or as gaining an unfair advantage with respect to others [16]. Ibrahim et al. [42] provided an illustration of this tension by showing that educators perceived the use of ChatGPT for assignments differently than students: While students largely see the potential and many intend to use it, educators are inclined to label its undisclosed use as plagiarism. The main objective of our research was to determine whether personality traits that may be indicative of ‘bending the rules’, such as Machiavellianism, impulsivity, and sensation seeking, correlate with ChatGPT usage.

From our ChatGPT Acceptance Scale, we extracted two negatively correlating factors: Effectiveness and Concerns. These two factors are consistent with other questionnaires that identified both the potential and concerns associated with AI [72, 75]. The extraction of negatively correlating factors provides a more refined insight compared to other ChatGPT research which identified strong positive correlations between facets of acceptance, such as performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence [29, 49, 56, 57, 79]. Such correlations may be due to common method variance and hard to statistically disentangle from each other (for a critique, see [22]). In our study, ChatGPT Effectiveness was strongly predictive of frequency of use (r = 0.57, r = 0.59 in Questionnaires 1 and 2), while ChatGPT Concerns were negatively predictive (r = − 0.36; r = − 0.31). The negative correlation between ChatGPT usage and age (r = − 0.21; r = − 0.22) corresponds with findings from a research panel [92] and research on ChatGPT that used web tracking, which showed that older individuals use ChatGPT less frequently [46]. Additionally, we found a strong correlation between perceived effectiveness of ChatGPT and a general propensity to trust machines (r = 0.45). These findings illustrate the criterion validity of our ChatGPT Acceptance Scale and contribute to the broader nomological net of ChatGPT acceptance by linking it to user demographics, perceptions of effectiveness, and trust in technology.

Regarding the prediction of ChatGPT from personality traits, Questionnaire 1 yielded mixed results: After controlling for age, gender, educational level, and country, we found that one Machiavellianism item (manipulation tactics), as well as low non-planning impulsivity (i.e., planning for the future), were predictors (r > 0.10) of ChatGPT usage. Although, in line with our hypotheses, sensation seeking and low neuroticism scores were predictive of ChatGPT use, these relationships were not robust enough to withstand statistical control for the above-mentioned confounders.

While the use of single items is not necessarily invalid and may, in fact, be preferred in certain instances [2, 5], we introduced more comprehensive personality scales in Questionnaire 2. Specifically, this questionnaire included a 9-item Machiavellianism scale along with a 44-item scale designed to measure the Big Five personality traits. From Questionnaire 2, it was particularly evident that Machiavellianism had predictive value for ChatGPT usage (r = 0.22) and for an opportunistic attitude towards ChatGPT (r = 0.30). These correlations indicate that respondents who indicate applying clever manipulation or strategic planning are more inclined to make clever use of ChatGPT, without disclosing this. Our results are consistent with Greitemeyer and Kastenmüller [34], who found positive associations between Dark Triad traits and the intention to use chatbots for cheating purposes.

The correlations between ChatGPT usage and personality traits are moderate in strength, which can be attributed to the generic and context-free nature of personality traits, in contrast to the ChatGPT Effectiveness and Concerns factor scores, which pertain to ChatGPT itself. Additionally, the correlations we have identified do not necessarily represent a causal relationship, wherein personality traits predispose one to the use of ChatGPT. It is conceivable that the direction of causality is reversed, where ChatGPT induces a sense of Machiavellianism. For example, using ChatGPT might reinforce the impression that one has gained an advantage over others.

A limitation of our study is its reliance on the Prolific population. Although Prolific is a highly regarded platform in terms of data quality (e.g., [78]), the usage of an online sample risks self-selection and demographic biases. Furthermore, it is still unknown how the observed national differences can be explained (see the Supplementary Material for the mean scores per country). For example, although it is possible that respondents from the UK were more negative about ChatGPT due to their higher mean age, other explanations could also be valid. One such explanation is that people in the UK, being more proficient in English, might benefit less from ChatGPT for tasks that require writing in English.

In conclusion, this research examined ChatGPT usage in relation to personality traits in a total sample of 3956 respondents. Supported by our findings, we posit that there exist moral tensions associated with the use of ChatGPT, where more opportunistic individuals use the tool to their advantage. This phenomenon is also recognizable in the academic system, where texts are regularly submitted that are clearly ChatGPT-assisted without disclosure [20]. Knowledge of the personality characteristics underlying such behaviors can help understand how to work towards transparent solutions. With over 100 million users, ChatGPT has undoubtedly become deeply ingrained in our society, predominantly among the younger generation [18, 90]. We advise authorities—including legislators, employers, publishers, and educators—to become well-informed about the potential of ChatGPT and other large language models and address the identified moral concerns by means of clear policies.

Data availability

Data and scripts that reproduce the analyses in the paper are available at https://doi.org/10.4121/e2e3ac25-e264-4592-b413-254eb4ac5022.

References

Akbar MA, Khan AA, Liang P. Ethical aspects of ChatGPT in software engineering research. IEEE Trans Artif Intell. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAI.2023.3318183.

Allen MS, Iliescu D, Greiff S. Single item measures in psychological science: a call to action. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2022;38(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000699.

Aplin-Houtz MJ, Leahy S, Willey S, Lane EK, Sharma S, Meriac J. Tales from the dark side of technology acceptance: the Dark Triad and the technology acceptance model. Empl Responsib Rights J. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-023-09453-6.

Bartholomew DJ, Deary IJ, Lawn M. The origin of factor scores: Spearman, Thomson and Bartlett. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2009;62(3):569–82. https://doi.org/10.1348/000711008X365676.

Bergkvist L, Rossiter JR. The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. J Mark Res. 2007;44(2):175–84. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.44.2.175.

Bin-Nashwan SA, Sadallah M, Bouteraa M. Use of ChatGPT in academia: academic integrity hangs in the balance. Technol Soc. 2023;75: 102370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102370.

Brauner P, Hick A, Philipsen R, Ziefle M. What does the public think about artificial intelligence?—a criticality map to understand bias in the public perception of AI. Front Comput Sci. 2023;5:1113903. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2023.1113903.

Brooks C. With little employer oversight, ChatGPT usage rates rise among American workers. 2023. https://www.business.com/technology/chatgpt-usage-workplace-study

Bubeck S, Chandrasekaran V, Eldan R, Gehrke J, Horvitz E, Kamar E, Lee P, Lee YT, Li Y, Lundberg S, Nori H, Palangi H, Ribeiro MT, Zhang Y. Sparks of artificial general intelligence: early experiments with GPT-4. arXiv. 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.12712.

Bulduk A. But why? A study into why upper secondary school students use ChatGPT: understanding students’ reasoning through Jean Baudrillard’s theory. Sweden: Karlstad University; 2023.

Campbell SH. What is human about writing?: writing process theory and ChatGPT. ResearchSquare. 2023. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3208562/v1.

Cardon P, Fleischmann C, Aritz J, Logemann M, Heidewald J. The challenges and opportunities of AI-assisted writing: developing AI literacy for the AI age. Bus Prof Commun Q. 2023;86(3):257–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/23294906231176517.

Cardon PW, Getchell K, Carradini S, Fleischmann C, Stapp J. Generative AI in the workplace: employee perspectives of ChatGPT benefits and organizational policies. SocArXiv. 2023. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/b3ezy.

Chan CKY, Lee KKW. The AI generation gap: are Gen Z students more interested in adopting generative AI such as ChatGPT in teaching and learning than their Gen X and millennial generation teachers? Smart Learning Environ. 2023;10:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-023-00269-3.

Choudhury A, Shamszare H. Investigating the impact of user trust on the adoption and use of ChatGPT: survey analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25: e47184. https://doi.org/10.2196/47184.

Currie GM. Academic integrity and artificial intelligence: Is ChatGPT hype, hero or heresy? Semin Nucl Med. 2023;53(5):719–30. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2023.04.008.

Davis FD. A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results (Doctoral dissertation). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1985.

Denejkina A. Young people’s perception and use of Generative AI. 2023. https://www.researchsociety.com.au/news-item/13748/young-peoples-perception-and-use-of-generative-ai

De Winter JCF. Can ChatGPT pass high school exams on English language comprehension? Int J Artif Intell Educ. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-023-00372-z.

De Winter JCF, Dodou D, Stienen AHA. ChatGPT in education: empowering educators through methods for recognition and assessment. Informatics. 2023;10(4):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics10040087.

De Winter JCF, Hancock PA. Reflections on the 1951 Fitts list: do humans believe now that machines surpass them? Proceedings of the 6th international conference on applied human factors and ergonomics (AHFE), Las Vegas, NV, 5334–5341. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2015.07.641.

De Winter JCF, Nordhoff S. Acceptance of conditionally automated cars: just one factor? Trans Res Interdiscip Perspect. 2022;15: 100645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2022.100645.

Dreibelbis E. These professions already use AI every day: Here’s what they’re doing. 2023. https://uk.pcmag.com/ai/148180/these-professions-already-use-ai-every-day-heres-what-theyre-doing.

Dwivedi YK, Kshetri N, Hughes L, Slade EL, Jeyaraj A, Kar AK, Baabdullah AM, Koohang A, Raghavan V, Ahuja M, Albanna H, Albashrawi MA, Al-Busaidi AS, Balakrishnan J, Barlette Y, Basu S, Bose I, Brooks L, Buhalis D, Wright R. “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. Int J Inf Manag. 2023;71:102642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642.

Dzindolet MT, Peterson SA, Pomranky RA, Pierce LG, Beck HP. The role of trust in automation reliance. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2003;58:697–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00038-7.

Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol Methods. 1999;4(3):272–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272.

Fitts PM. Human engineering for an effective air-navigation and traffic-control system. Washington, DC: National Research Council; 1951.

Forman N, Udvaros J, Avornicului MS. ChatGPT: a new study tool shaping the future for high school students. Int J Adv Nat Sci Eng Res. 2023;7(4):95–102. https://doi.org/10.59287/ijanser.562.

Foroughi B, Senali MG, Iranmanesh M, Khanfar A, Ghobakhloo M, Annamalai N, Naghmeh-Abbaspour B. Determinants of intention to use ChatGPT for educational purposes: findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Int J Human-Comput Interact. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2226495.

Gabbiadini A, Ognibene D, Baldissarri C, Manfredi A. Does ChatGPT pose a threat to human identity? SSRN. 2023. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4377900.

Gignac GE, Szodorai ET. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personal Individ Differ. 2016;102:74–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069.

Goodfellow C, Hardoon D, Inchley J, Leyland AH, Qualter P, Simpson SA, Long E. Loneliness and personal well-being in young people: moderating effects of individual, interpersonal, and community factors. J Adolesc. 2022;94(4):554–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12046.

Gorichanaz T. Accused: how students respond to allegations of using ChatGPT on assessments. Learning. 2023;9(2):183–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2023.2254787.

Greitemeyer T, Kastenmüller A. HEXACO, the Dark Triad, and Chat GPT: who is willing to commit academic cheating? Heliyon. 2023;9(9):e19909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19909.

Gupta M, Akiri C, Aryal K, Parker E, Praharaj L. From ChatGPT to ThreatGPT: impact of Generative AI in cybersecurity and privacy. IEEE Access. 2023;11:80218–45. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3300381.

Hair JF Jr, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis. 8th ed. Hampshire, UK: Cengage Learning; 2019.

Hendrickson AE, White PO. Promax: a quick method for rotation to oblique simple structure. Br J Stat Psychol. 1964;17(1):65–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1964.tb00244.x.

Hern A, Milmo D. ‘I didn’t give permission’: do AI’s backers care about data law breaches? 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/apr/10/i-didnt-give-permission-do-ais-backers-care-about-data-law-breaches

Hoff KA, Bashir M. Trust in automation: integrating empirical evidence on factors that influence trust. Hum Factors. 2015;57(3):407–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720814547570.

Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen P, Lorch EP, Donohew RL. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Personal Individ Differ. 2002;32(3):401–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00032-0.

Hu K. ChatGPT sets record for fastest-growing user base—analyst note. 2023. https://www.reuters.com/technology/chatgpt-sets-record-fastest-growing-user-base-analyst-note-2023-02-01

Ibrahim H, Liu F, Asim R, Battu B, Benabderrahmane S, Alhafni B, Adnan W, Alhanai T, AlShebli B, Baghdadi R, Bélanger JJ, Beretta E, Celik K, Chaqfeh M, Daqaq MF, El Bernoussi Z, Fougnie D, Garcia de Soto B, Gandolfi A, Zaki Y. Perception, performance, and detectability of conversational artificial intelligence across 32 university courses. Sci Rep. 2023;13:12187. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38964-3.

Jishnu D, Srinivasan M, Dhanunjay GS, Shamala R. Unveiling student motivations: a study of ChatGPT usage in education. ShodhKosh. 2023;4(2):65–73. https://doi.org/10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i2.2023.503.

John OP, Srivastava S. The Big-Five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: theory and research, vol. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. p. 102–38.

Jones DN, Paulhus DL. Introducing the Short Dark Triad (SD3): a brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment. 2014;21(1):28–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191113514105.

Kacperski C, Ulloa R, Bonnay D, Kulshrestha J, Selb P, Spitz A. Who are the users of ChatGPT? Implications for the digital divide from web tracking data. arXiv. 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.02142.

Kaya F, Aydin F, Schepman A, Rodway P, Yetişensoy O, Demir Kaya M. The roles of personality traits, AI anxiety, and demographic factors in attitudes toward artificial intelligence. Int J Human-Comput Int. 2024;40(2):497–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2151730.

Kieslich K, Lünich M, Marcinkowski F. The threats of artificial intelligence scale (TAI). Development, measurement and test over three application domains. Int J Soc Robot. 2021;13:1563–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-020-00734-w.

Kim H-J. A study on the intentions of ChatGPT users using the extended UTAUT model. J Digit Content Soc. 2023;24(7):1465–73. https://doi.org/10.9728/dcs.2023.24.7.1465.

Konstantis K, Georgas A, Faras A, Georgas K, Tympas A. Ethical considerations in working with ChatGPT on a questionnaire about the future of work with ChatGPT. AI and Ethics. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00312-6.

Korkmaz A, Aktürk C, Talan T. Analyzing the user’s sentiments of ChatGPT using Twitter data. Iraqi J Comput Sci Math. 2023;4(2):202–14. https://doi.org/10.52866/ijcsm.2023.02.02.018.

Lakhal S, Khechine H. Relating personality (Big Five) to the core constructs of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. J Comput Educ. 2017;4:251–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-017-0086-5.

Li H. Rethinking human excellence in the AI age: the relationship between intellectual humility and attitudes toward ChatGPT. Personality Individ Differ. 2023;215: 112401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112401.

Li J, Huang J-S. Dimensions of artificial intelligence anxiety based on the integrated fear acquisition theory. Technol Soc. 2020;63: 101410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101410.

Liang Y, Lee SA. Fear of autonomous robots and artificial intelligence: evidence from national representative data with probability sampling. Int J Soc Robot. 2017;9:379–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-017-0401-3.

Liu G, Ma C. Measuring EFL learners’ use of ChatGPT in informal digital learning of English based on the technology acceptance model. Innov Lang Learn Teach. 2023;18(2):125–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2023.2240316.

Ma X, Huo Y. Are users willing to embrace ChatGPT? Exploring the factors on the acceptance of chatbots from the perspective of AIDUA framework. Technol Soc. 2023;75: 102362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102362.

Májovský M, Černý M, Kasal M, Komarc M, Netuka D. Artificial Intelligence can generate fraudulent but authentic-looking scientific medical articles: Pandora’s box has been opened. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25: e46924. https://doi.org/10.2196/46924.

McClure PK. “You’re fired”, says the robot: the rise of automation in the workplace, technophobes, and fears of unemployment. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2018;36(2):139–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317698637.

Merritt SM, Huber K, LaChapell-Unnerstall J, Lee D. Continuous calibration of trust in automated systems (report no. AFRL-RH-WP-TR-2014-0026). Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH: Air Force Research Laboratory. 2014.

Morocco-Clarke A, Sodangi FA, Momodu F. The implications and effects of ChatGPT on academic scholarship and authorship: a death knell for original academic publications? Inf Commun Technol Law. 2023;33(1):21–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600834.2023.2239623.

Nordhoff S, De Winter JCF. Why do drivers and automation disengage the automation? Results from a study among Tesla users. ResearchGate. 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369475727_Why_do_drivers_and_automation_disengage_the_automation_Results_from_a_study_among_Tesla_users.

OpenAI. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv. 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.08774.

Parasuraman R, Sheridan TB, Wickens CD. Situation awareness, mental workload, and trust in automation: Viable, empirically supported cognitive engineering constructs. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak. 2008;2(2):140–60. https://doi.org/10.1518/155534308X284417.

Peters MA, Jackson L, Papastephanou M, Jandrić P, Lazaroiu G, Evers CW, Cope B, Kalantzis M, Araya D, Tesar M, Mika C, Chen L, Wang C, Sturm S, Rider S, Fuller S. AI and the future of humanity: ChatGPT-4, philosophy and education—critical responses. Educ Philos Theory. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2023.2213437.

Petricini T, Wu C, Zipf ST. Perceptions about generative AI and ChatGPT use by faculty and college students. EdArXiv. 2023. https://doi.org/10.35542/osf.io/jyma4.

Qualtrics. Qualtrics XM - Qualtrics - #1 XM platform. 2023. https://www.qualtrics.com.

Raman R, Mandal S, Das P, Kaur TJP, Sanjanasri JP, Nedungadi P. University students as early adopters of ChatGPT: innovation diffusion study. Research Square. 2023. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2734142/v1.

Rammstedt B, John OP. Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J Res Pers. 2007;41(1):203–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001.

Roose K. A.I. poses ‘risk of extinction,’ industry leaders warn. 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/30/technology/ai-threat-warning.html

Sallam M, Salim NA, Barakat M, Al-Mahzoum K, Al-Tammemi AB, Malaeb D, Hallit R, Hallit S. Assessing attitudes and usage of ChatGPT in Jordan among health students: a validation study of the technology acceptance model-based scale (TAME-ChatGPT). JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9: e48254. https://doi.org/10.2196/48254.

Schepman A, Rodway P. Initial validation of the general attitudes towards Artificial Intelligence Scale. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2020;1:100014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2020.100014.

Sedaghat S. Success through simplicity: what other artificial intelligence applications in medicine should learn from history and ChatGPT. Ann Biomed Eng. 2023;51:2657–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-023-03287-x.

Shoufan A. Exploring students’ perceptions of ChatGPT: thematic analysis and follow-up survey. IEEE Access. 2023;11:38805–18. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3268224.

Sindermann C, Sha P, Zhou M, Wernicke J, Schmitt HS, Li M, Sariyska R, Stavrou M, Becker B, Montag C. Assessing the attitude towards artificial intelligence: introduction of a short measure in German, Chinese, and English language. KI - Künstliche Intelligenz. 2021;35:109–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13218-020-00689-0.

Skjuve M, Følstad A, Brandtzaeg PB. The user experience of ChatGPT: findings from a questionnaire study of early users. Proc 5th Int Conf Conversat User Interface Eindh Neth. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1145/3571884.3597144.

Spinella M. Normative data and a short form of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Int J Neurosci. 2007;117(3):359–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207450600588881.

Stagnaro MN, Druckman J, Arechar AA, Willer R, Rand D. Representativeness versus attentiveness: a comparison across nine online survey samples. PsyArXiv. 2024. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/h9j2d.

Strzelecki A. To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Int Learn Environ. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2209881.

Subaveerapandiyan A, Vinoth A, Tiwary N. Netizens, academicians, and information professionals’ opinions about AI with special reference to ChatGPT. arXiv. 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.07136.

Svendsen GB, Johnsen J-AK, Almås-Sørensen L, Vittersø J. Personality and technology acceptance: the influence of personality factors on the core constructs of the technology acceptance model. Behav Inf Technol. 2013;32(4):323–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2011.553740.

Tian Y, Tong C, Lee LH, Mogavi RH, Liao Y, Zhou P. Last week with ChatGPT: a Weibo study on social perspective regarding ChatGPT for education and beyond. arXiv. 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.04325.

Tschang FT, Almirall E. Artificial intelligence as augmenting automation: implications for employment. Acad Manag Perspect. 2021;35(4):642–59. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2019.0062.

Ul Haque M, Dharmadasa I, Sworna ZT, Rajapakse RN, Ahmad H. “I think this is the most disruptive technology": exploring sentiments of ChatGPT early adopters using Twitter data. arXiv. 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.05856.

Van der Laan JD, Heino A, De Waard D. A simple procedure for the assessment of acceptance of advanced transport telematics. Trans Res Part C Emerg Technol. 1997;5(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-090X(96)00025-3.

Van Dongen JDM, De Groot M, Rassin E, Hoyle RH, Franken IHA. Sensation seeking and its relationship with psychopathic traits, impulsivity and aggression: a validation of the Dutch Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS). Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. 2022;29(1):20–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2020.1821825.

Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003;27(3):425–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540.

Von Garrel J, Mayer J. Artificial Intelligence in studies—use of ChatGPT and AI-based tools among students in Germany. Hum Soc Sci Commun. 2023;10:799. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02304-7.

Wang Y-Y, Wang Y-S. Development and validation of an artificial intelligence anxiety scale: an initial application in predicting motivated learning behavior. Interact Learn Environ. 2022;30(4):619–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1674887.

Wodecki, B. A generation gap emerges in the use of AI at work - Survey. 2023. https://aibusiness.com/verticals/generation-ai-71-of-young-professionals-embrace-ai-in-the-workplace.

Wu X, Duan R, Ni J. Unveiling security, privacy, and ethical concerns of ChatGPT. J Inf Intell. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiixd.2023.10.007.

YouGov. Daily survey: ChatGPT. 2023. https://docs.cdn.yougov.com/p3j2eqjz5c/tabs_ChatGPT_20230124.pdf.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Joost de Winter, Yke Bauke Eisma; Methodology: Joost de Winter, Yke Bauke Eisma; Formal analysis: Joost de Winter; Investigation: Joost de Winter, Dimtra Dodou; Writing—original draft preparation: Joost de Winter; Writing—review and editing: Joost de Winter, Dimitra Dodou, Yke Bauke Eisma; Resources: Dimitra Dodou.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Delft University of Technology (Reference Number 3411). Respondents provided informed consent via a dedicated questionnaire item.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional file 1.

Additional results and tables.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Winter, J., Dodou, D. & Eisma, Y.B. Personality and acceptance as predictors of ChatGPT use. Discov Psychol 4, 57 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00161-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00161-2