Abstract

Studies have documented the stress and burnout related to medical residency and the need to design programs to reduce burnout. This study evaluates the effectiveness of an intervention for psychiatric residents to improve resiliency and reduce burnout. A six-session program was offered that included mindfulness, self-regulation, and coping strategies. The program was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Standardized assessment tools measuring perceived stress, mindfulness, professional quality of life, burnout and resiliency were used pre and post program. Burnout was defined based on any one of the three criteria for burnout: high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization or low personal accomplishment. Six one-hour sessions were offered to residents during protected time during the academic year. Analysis compared residents who met and did not meet criteria for burnout pre and post program. Twenty-seven residents provided informed consent, and 23 had complete data on the indicators of burnout. Seven of 23 met criteria for burnout and those significantly reduced their perceived stress, emotional exhaustion, burnout and increased their mindfulness scores post program (p < 0.05). The residents who improved their mindfulness scores post program significantly improved resiliency, reduced secondary traumatic stress and perceived stress (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the scores of residents who did not meet criteria for burnout. Residents experiencing burnout significantly improved indicators of burnout, while those not reporting burnout did not worsen. Mindfulness was an important component of this program since residents gaining in mindfulness skills also reduced scores on indicators of burnout post program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Many studies have documented high stress related to medical residency training [1, 2]. Stress can be defined as a “state of homeostasis being challenged, including both system stress and local stress.” [3] More specifically, high perceived stress, one’s perception of their stress, has been associated with decreased well-being and increased burnout. Many system factors contribute to this risk of burnout for residents which is defined as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and/or reduced personal achievement. Along with continuing to address these system factors to decrease burnout, some studies have shown promise that resilience and mindfulness can mitigate burnout. Mindfulness, “the awareness that emerges through paying attention, on purpose, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment,” and resiliency, being able to bounce back and grow from adversity, are skills that can be further developed.

Numerous studies have reported burnout rates ranging from 7 to 80%, depending on the specific medical specialty sampled [4]. Long hours, responsibility for call, little control over schedules, and little time for self-care all contribute to feeling overwhelmed by stress.

In a review of studies specifically focusing on psychiatry residents, Chan et al. [4] found an overall burnout rate of 33.7%, based on any one of the three criteria for burnout (high emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, low personal accomplishment). Factors found to be associated with burnout include junior training level, high workload, non-parental status, and perceived lack of clinical supervision [4]. Cloverdale and colleagues identified several stressful challenges found in psychiatric residencies including aggression by patients, attendance at disasters, working with victims of violence, and involuntarily detentions [5].

Managing patients who are chronically suicidal, and the rarer occurrence of patient suicide represents a particular source of stress for psychiatry residents. Although residents in other specialties identify serious mental health issues in their patients, those residents are not responsible for treatment planning, hospitalization or monitoring suicidal patients [6, 7]. Most clinicians can cope with the demands of challenging patients, but in some, the emotional impact can impair their personal functioning and well-being. Additionally, clinicians are at risk of experiencing secondary traumatic stress, “the stress deriving from helping others who are suffering or who have been traumatized” mirroring the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. [8, 9]

A previous study compared the burnout rates and resiliency in five groups of medical residents (Family Medicine, Neurology, Emergency Medicine, Internal Medicine and Psychiatry). The overall percentage of burnout was 45% across all five residencies. Psychiatry residents had the lowest scores on the MBI (Maslach Burnout Inventory), the lowest scores in Secondary Traumatic Stress, and the highest score in compassion satisfaction [10]. Compassion satisfaction, the positive feeling from helping others, is inversely associated with burnout.

Reports of interventions designed to improve resiliency and decrease burnout are more limited than studies addressing the needs for such programs. In a controlled study with family medicine residents in all years of residency, it was found that a program focusing on building resiliency and reducing burnout was associated with improvements in factors related to burnout [11]. The intervention group showed significantly lower scores on depersonalization and emotional exhaustion immediately after the program. Mindfulness is one of the major evidence-based interventions found to promote resilience for physicians. Both Krasner et al. [12] and West et al. [13] reported encouraging results when incorporating mindfulness content into resiliency programs. However, studies evaluating mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatry residents have yielded inconsistent results [14,15,16]. The length of the intervention seems to be important. Studies lasting just a few hours [15] appear to have little if any impact while substantial benefits were reported after an eight-hour program [14].

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) [17] has recently emphasized physician well-being as a key component of professionalism. It is part of the Common Program Requirements, and individual specialties also have well-being as a sub-competency of professionalism in their specialty milestones. Interventions like the one described in this paper, can help programs address some of these requirements, such as paying attention to burnout, providing access to self-screening tools, enhancing meaning in the work of a physician, and assisting residents to make plans to promote personal well-being. The objective of this study was to investigate the effects of a program on indicators of burnout and resiliency in psychiatry residents.

2 Methods

2.1 Protocol

Throughout the academic years 2017–2020, all psychiatry residents were required to attend 6 one-hour sessions each year on building resiliency and reducing burnout as part of their already scheduled weekly didactics. Didactics constitute protected time when residents did not have clinical responsibilities. The program was interactive, and skill based. The protocol and consent form were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the institution. Residents were invited to provide informed consent and sign the consent form, but this was not required as part of the didactics. The residents were asked to complete a set of questionnaires which are described in the section on Instruments at the beginning of the first session. The same questionnaires were repeated at the last session, towards the end of the academic year. At that time residents also completed a program evaluation form.

2.2 Sessions

We have designed and implemented a program for residents at our academic medical center focusing on building resiliency and promoting wellness. The interactive sessions used evidence-based methods including stress management, mindfulness, and positive psychology. The sessions were led by three faculty members that had designed the program and involved didactic presentations, group discussion and guided relaxation exercises. The residents were given a needs assessment at the first session to help determine which topics would be the most helpful to focus on during the year. The main themes of the sessions were: awareness of stress responses, identifying personal strengths, building the growth mindset, coping strategies, stress management, mindfulness, physiological relaxation, breath pacing, dealing with perceptions of failure and managing fatigue. Each session ended with an opportunity to practice a skill such as relaxation, imagery, or mindfulness meditation led by one of the faculty members. Not all residents attended all sessions; vacation, illness or post call were factors in incomplete attendance.

2.3 Instruments

Residents completed a short demographic form indicating their age, gender, ethnicity, relationship status, and race. Standardized, validated assessments comprised the following: The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) consists of three subscales that measure Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Personal Accomplishment [18]. Burnout is defined as high scores in Emotional Exhaustion or Depersonalization, and/or low Personal Accomplishment. The Professional Quality of Life Scale (PQoLScale) also comprises three subscales (Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress) to assess the sense of satisfaction in doing a job well, feelings of extreme emotional tiredness due to work, and the impact of exposure to the trauma of others [19]. The Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) captures the experience of mindfulness and mindlessness states by scaling multiple example statements in specific to day-to-day circumstances [20]. The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale is an assessment of a subject’s ability to bounce back from stressful situations [21]. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) questionnaire measures the extent to which subjects consider situations to be stressful [22]. The evaluation form comprised questions on the usefulness of the program, on a 10-point scale (1 = not at all satisfied to 10 = extremely satisfied). Residents were also asked to indicate if they would recommend the program to another resident.

2.4 Analysis

Statistical analyses comprised demographics, MANOVA followed by post hoc tests, and paired t-tests. The number of residents in each analysis varies because of missing data.

3 Results

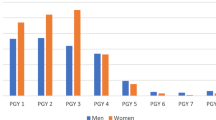

Twenty-seven residents provided informed consent. There were 16 males and 11 females. Six were single, 4 were in a relationship, 6 were living with a partner and 10 were married. There were 24 non-Hispanic, 2 Hispanic and 1 did not answer that question. The ethnicity breakdown was 11 Caucasian, 1 African American, 12 Asian, 2 biracial and 1 did not answer. The average age was 30.4 (range 26 to 43) years.

Paired t-tests were used to analyze pre and post values on the dependent variables for all residents. There were no significant differences at the p < 0.05 level. Perceived stress decreased from 16.1 (7.4) to 13.8 (7.1), but the change was not significant at p < 0.05. (p < 0.065).

Residents were divided based on whether they met criteria on any one of the 3 indicators of burnout (high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, or low personal accomplishment) [18]. The overall percentage of burnout based on this criterion was 30%. Pre- program values of all dependent variables were compared between those who met criteria and those who did not meet criteria using MANOVA followed by post hoc tests as shown in (Table 1). MANOVA was significant at p < 0.028.

Post hoc testing showed significant differences between the groups in perceived stress, emotional exhaustion, burnout, and mindfulness. Residents who met criteria for burnout had higher scores in perceived stress, emotional exhaustion, burnout, and lower scores on mindfulness. Subsequently, t-tests were used to elucidate the occurrence of changes in the dependent variables pre and post the program. The residents meeting criteria for burnout preprogram showed a significant decrease in perceived stress (p < 0.028) and a significant increase in mindfulness (p < 0.036). There was a trend for a decrease in emotional exhaustion (p < 0.07) and lower scores on burnout which were not significant. Analysis of the scores for the residents who did not meet criteria for burnout showed no significant changes when preprogram and post program assessments were compared.

The next step in the analysis was to carry out a frequency distribution on each of the dependent variables. Based on the distribution, the group was divided into those residents whose scores were at the published norms for each variable (shown in Table 1) and those residents scores who did not meet the published norms for each variable. Values of the dependent variables preprogram, and post program were compared in the group of residents who met or did not meet the published norms using paired t-tests. In the group whose scores indicated a risk for burnout, post program scores showed significant decreases in emotional exhaustion (p < 0.028) and in secondary traumatic stress (p < 0.011). There was also a significant increase in mindfulness (p < 0.011). The residents whose scores met the published norms (no major indicators of burnout) showed no significant improvements or worsening in indictors of burnout.

We subsequently identified those residents who demonstrated a positive change in mindfulness from preprogram to post program to determine if residents improving in mindfulness evidenced positive changes in any of the other variables.

As shown in Table 2, there were significant improvements in the Connor Davidson resilience scale (increase) (p < 0.05), the secondary traumatic stress scale (decrease) (p < 0.019), and the perceived stress scale (decrease) (p < 0.048). Residents who did not change or decreased their mindfulness scores showed significant decreases in Connor resiliency (p < 0.044) and in personal accomplishment (p < 0.033).

Analysis of the program evaluations showed that residents rated their degree of satisfaction with the program as 6.4 on a 10-point scale, indicating moderate satisfaction. The majority of residents indicated that they would recommend the program to other residents.

4 Discussion

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has recognized the need to address medical residents' well-being and prevent burnout [17]. The recommendations are general but mention coping, and balancing life as a physician as examples. Our program was designed to enhance emotional resiliency and reduce indicators of burnout. The results of our study demonstrate that medical psychiatric residents, specifically those residents who are showing signs of burnout, can benefit from interventions to build skills known to reduce burnout and increase resiliency. In particular, we found that residents meeting one criterion for burnout experienced a significant decrease in perceived stress and a significant increase in mindfulness following the intervention. Residents who scored outside of the published norms on the other measures of stress used in the study also clearly benefited from the intervention. They showed a significant decrease in emotional exhaustion and in secondary traumatic stress, as well as a significant increase in mindfulness.

Bentley et al. [14] and Goldhagen et al. [16] also conducted intervention studies with psychiatry residents. The Bentley study was more similar in design and results to the current study and resulted in significant, positive changes in stress related measures after the intervention [14]. In the Goldhagen et al. [16] study, the intervention was presented over 3 h and showed no significant results at the end of the intervention, nor at the one-month follow-up. Szuster et al. found that longer term programs (16 weeks vs 4 weeks) are needed to maintain gains from a wellness program among a mixed group of residents. [23] Future studies are needed to define more clearly the optimal number of sessions to produce significant effects.

We found that an increase in mindfulness was associated with positive changes in several stress measures. For this reason, we concur with the findings from other researchers who have made mindfulness training a central component of interventions to address burnout [12, 13, 23]. Among these studies, Krasner et al. [12] also looked at the association of change in mindfulness scores with changes in stress measures and reported that an increase in mindfulness scores was significantly associated with a decrease in stress measures. Szuster et al. had a format similar to the length of our intervention, a 6-session mindfulness-based program that showed significant improvements in professional fulfillment, work exhaustion, interpersonal disengagement, and anxiety in the residents in the intervention group. [23] The discovery of this association between mindfulness and reduced stress measures is important since it contributes to the quest to identify which specific elements of an intervention program are most effective in producing positive change.

A previous study with family medicine residents which offered a similar intervention also produced positive but different effects [11]. In comparison to controls, the family medicine residents showed decreases in emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. The reason for this difference is not clear but it could be related to differences in stress level of the family medicine residents when compared to psychiatry residents. An earlier study [10] of 5 medical specialties found that psychiatry residents did demonstrate a lower level of burnout when compared to residents from other medical specialties.

Relatively greater benefits were realized by residents who were reporting higher levels of burnout initially. This is understandable intuitively since those who were most burned out had the greater capacity for improvement, even though the residents who did not meet criteria for burnout also experienced some benefit.

Support from the program director, psychiatry faculty and amongst the residents themselves was in evidence during the sessions and frequently observed during the residents’ workday. Similar effects of social support have been noted in competitive athletics [24]. Interpersonal relatedness within the resident groups also had a positive effect on resident well-being in a recent study. [23]

There was a trend in our findings for all residents to report a decrease in perceived stress following the intervention. In addition, despite stressors that are part of residency [5], no significant increases in stress scores were observed in the total group at the end of the academic year. These results are similar to findings from two studies conducted with medical students [25, 26]. Those students entering the stress management program with higher anxiety and greater numbers of life events in the past year demonstrated significant improvements post program in comparison to other students who began the program with lower anxiety and fewer life events.

It is important to identify which interventions have the most impact in reducing resident burnout. There have been recent studies on a wide variety of interventions including resident retreats [27], on-line physician well-being courses [28], a humanistic mentorship program [29] and a mind–body skills group in psychiatric residency training [30]. A systemic review of skill-based programs used to reduce physician burnout in graduate medical education was published in 2021 [31]. Their conclusion was that there is not a consistent pattern of successful or unsuccessful programs based on content. But most programs that were successful in reducing burnout incorporated multiple teaching methods and were serial programs that occurred during residents’ protected education time. [31]

5 Limitations

The small sample and the absence of a control group should be considered. The fact that the study was conducted at only one institution limits the generalizability of the findings. Only the scores of residents who gave permission were included in the analyses. Although this restriction was necessary and appropriate ethically, the generalizability is affected. Because the second assessments were done at the end of the academic year, it is possible that the improvements observed were related to other factors (e.g. relief at the end of the academic year). We also recognize that systems changes may be necessary at academic institutions to reduce overall burnout in medical residents, but we did not address these issues.

In summary, our findings support the value of programs designed to build resiliency and reduce burnout. In addition, mindfulness should be considered a major component of such programs. Considering the specific needs and attitudes of psychiatry residents will make interventions presented to them most effective. Further research should study the relative value of intervention programs at each level of residency and attempt to identify which specific interventions have the most impact. It would also be valuable to track the long-term effects of the intervention.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of participant sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at the University of Toledo Medical Center.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Thrush CR, Guise JB, Gathright MM, Messias E, Flynn V, Belknap T, Thapa PB, Williams DK, Nada EM, Clardy JA. A one-year institutional view of resident physician burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(4):361–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-019-01043-9.

Ebrahimi S, Kargar Z. Occupational stress among medical residents in educational hospitals. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2018;8(30):51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40557-018-0262-8.

Lu S, Wei F, Li G. The evolution of the concept of stress and the framework of the stress system. Cell Stress. 2021;5(6):76–85. https://doi.org/10.15698/cst2021.06.250.

Chan MK, Chew QH, Sim K. Burnout and associated factors in psychiatry residents: a systematic review. Int J Med Educ. 2019;30(10):149–60. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5d21.b621.

Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, Brenner AM, Louie AK, Guerrero APS, Roberts LW. What are some stressful adversities in psychiatry residency training, and how should they be managed professionally? Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(2):145–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-019-01026-w.

Ruskin R, Sakinofsky I, Bagby RM, Dickens S, Sousa G. Impact of patient suicide on psychiatrists and psychiatric trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(2):104–10. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.28.2.104.

Chemtob C, Hamada R, Bauer G, et al. Patients’ suicides: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(2):224–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.145.2.224.

Vukčević Marković M, Živanović M. Coping with secondary traumatic stress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12881. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912881.PMID:36232179.

Figley C.R. Stress and the Family. Volume II. Brunner/Mazel; New York, NY, USA: 1983. Catastrophes: An overview of family reactions; pp. 3–20.

McGrady A, Brennan J, Riese A, McCartney, C. Effects of a Structured Resiliency Program on Indicators of Burnout in Five Medical Specialties. Poster Session Presented: at American Psychological Association Virtual Meeting; 2020.

Brennan J, McGrady A, Tripi J, Sahai A, Frame M, Stolting A, Riese A. Effects of a resiliency program on burnout and resiliency in family medicine residents. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2019;54(4–5):327–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217419860702.

Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, Quill TE. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284–93. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1384.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, Call TG, Davidson JH, Multari A, Romanski SA, Hellyer JM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527–33. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387.

Bentley PG, Kaplan SG, Mokonogho J. Relational mindfulness for psychiatry residents: a pilot course in empathy development and burnout prevention. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(5):668–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-018-0914-6.

Chaukos D, Chad-Friedman E, Mehta DH, Byerly L, Celik A, McCoy TH Jr, Denninger JW. SMART-R: a prospective cohort study of a resilience curriculum for residents by residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(1):78–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-017-0808-z.

Goldhagen BE, Kingsolver K, Stinnett SS, Rosdahl JA. Stress and burnout in residents: impact of mindfulness-based resilience training. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;25(6):525–32. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S88580.

ACGME. Physician Well-Being: The ACGME and Beyond. Chicago (IL): Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2018. https://www.acgme.org/newsroom/blog/2018/2/physician-well-being-the-acgme-and-beyond/. Accessed 6 July 2022.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL. Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). Mind Garden. 2016. https://www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory. Accessed 25 Jan 2019.

De La Rosa GM, Webb-Murphy JA, Fesperman SF, Johnston SL. Professional quality of life normative benchmarks. Psychol Trauma. 2018;10(2):225–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000263.

Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96.

Szuster R, Onoye J, Matsu C. Presence, resilience, and compassion training in clinical education (PRACTICE): a follow-up evaluation of a resident-focused wellness program. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15(2):237–43. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00422.1.

Zhang DF, Lyu B, Wu JT, Li WZ, Zhang KY. Effect of boxers’ social support on mental fatigue: Chain mediating effects of coach leadership behaviors and psychological resilience. Work-A J Prev Assess Rehabilit. 2023;76(4):1465–79. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-220478.

McGrady A, Brennan J, Lynch D, Whearty K. A wellness program for first year medical students. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2012;37(4):253–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-012-9198-x.

Brennan J, McGrady A, Lynch DJ, Schaefer P, Whearty K. A stress management program for higher risk medical students: preliminary findings. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2016;41(3):301–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-016-9333-1.

Taya M, Corines MJ, Sinha V, Schweitzer AD, Lo GK, Dodelzon K, Min RJ, Belfi L. Evaluating the impact of annual resident retreats on radiology resident wellbeing. Acad Radiol. 2024;31(2):409–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2023.10.062.

Ricker M, Brooks A, Bodine S, Lebensohn P, Maizes V. Well-being in residency: impact of an online physician well-being course on resiliency and burnout in incoming residents. Fam Med. 2021;53(2):123–8. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2021.314886.

Kobritz M, Nofi CP, Demyan L, Farno E, Fornari A, Kalyon B, Patel V. Implementation and assessment of mentoring and professionalism in training (MAP-IT): a humanistic curriculum as a tool to address burnout in surgical residents. J Surg Educ. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.11.002.

Ranjbar N, Erb M, Tomkins J, Taneja K, Villagomez A. Implementing a mind-body skills group in psychiatric residency training. Acad Psychiatry. 2022;46(4):460–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-021-01507-x.

Vasquez TS, Close J, Bylund CL. Skills-based programs used to reduce physician burnout in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(4):471–89. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-20-01433.1.

Acknowledgements

There was no financial support for this program. We thank the residency training director(s) for scheduling the sessions during didactic time and the residency coordinator(s) for help in scheduling.

Funding

There was no financial support for this program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Amy Riese, Angele McGrady, Julie Brennan, Denis Lynch, Daniel Valentine and Jordin Nowak. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Amy Riese and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states there is no conflict of interest. This project was IRB approved at the University of Toledo.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Riese, A., McGrady, A., Brennan, J. et al. The effects of a resiliency intervention program on indicators of resiliency and burnout in psychiatry residents. Discov Psychol 4, 42 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00155-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00155-0