Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant negative implications for individual wellbeing and many people accessed green spaces to help them cope with the demands of national lockdown restrictions. In response, the current study used Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) to investigate the experiences of ten UK based nature volunteers whose activities had been disrupted due to the UK COVID-19 lockdowns throughout 2020. Each nature volunteer participated in a semi-structured interview held on a virtual platform which invited them to explore their experiences in nature during the pandemic. Analysis identified three main themes. ‘Sensations of nature’ explored the sense of presence and oneness with nature that the volunteers felt when mindfully engaging with the sensations found in nature. ‘Stability from nature’ investigated the ways in which the volunteers found meaning in nature and the sense of comfort, stability and hope this provided. Finally, ‘Changing relationships with nature’ examined the greater environmental awareness that the volunteers experienced and the ways in which this led to a desire to give back to nature. It is argued that mindful engagement with nature enhances a sense of personal wellbeing and cultivates a connection to nature which encourages environmental concern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The world has undergone a global emergency because of the COVID-19 pandemic [1]. To prevent further spread, millions of people throughout the world were placed under strict lockdown, causing significant lifestyle changes [2]. During this time wellbeing was significantly impacted, with depression and anxiety scores rising during lockdown [3]. To combat isolation, many people turned to nature [4] with increased pedestrian activity observed in many natural areas [5]. Access to nature during the pandemic was beneficial for coping with the demands of lockdown and improving mental health [6]. Environmentally, responses have varied, with some displaying greater concern [7] and support for conservation [8] whereas others damaged nature through pollution from improper disposal of single use Personal Protective Equipment [9]. In response, this paper uses a qualitative approach to provide insight into the experiences of UK-based conservation volunteers with nature during the 2020 lockdowns. Given that this group experienced disruption to their nature volunteer work, and therefore their regular access to nature, during the pandemic they offer a unique perspective into the impact of the pandemic on nature experiences and the proposed importance of nature connectedness for improving personal wellbeing and environmental concern.

1.1 Nature and wellbeing

The importance of nature for wellbeing has been understood throughout human history [10]. Benefits relating to health and vitality discussed in ancient Greek and Roman texts are echoed in the modern era, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, with research finding that nature engagement can improve wellbeing [11]. This can in part be explained by Kaplan’s [12] Attention Restoration Theory (ART). In line with this approach, nature promotes restorative activities by engaging involuntary attention through four properties; distance from fatiguing activities; rich stimuli; soft fascination with the environment; and compatibility with needs [12].

Natural sounds have also been shown to restore mental stress both during and following the pandemic by evoking a sense of fascination with the environment which directs attention away from stressful situations [12, 13]. Similarly, natural tactile contact has been found to have a calming effect [14]. This suggests that immersing the senses in nature contributed to mental health during lockdown through cultivating calmness and tranquility [15].

Actively engaging with nature’s sensations can be considered a moment of interconnection [16]. This “experiential sense of oneness” with nature [17], encapsulates the importance of all nature to humans [18] and interconnection with nature suggests a meaningful relationship with something beyond oneself [19]. Connection to nature is strengthened when combined with mindfulness [19] and it has been demonstrated that simple exposure to nature encourages mindfulness [20]. To deepen a mindful understanding of human-nature interconnection Van Gordon et al. [21] highlighted the importance of ‘active awareness’ in nature through activities such as reflective questioning. It is suggested that this allows for a sense of meaning from nature through relating to the beauty and symbols that it holds.

Finding meaning is one of the pathways to nature connectedness [22] and therefore meaning mediates the relationship between nature connectedness and wellbeing [23]. Through applying stable concepts to a changing world [24] meaning can be found in the order of nature which persists despite the impermanence of societal norms and structures [25]. Nature provides a sense of timelessness, like that observed among indigenous cultures who connect with their ancestors through becoming in touch with the world before their time [26, 27]. According to Almass [28] nature is undergoing constant rebirth, continually unfolding in an eternal process of change in which it appears alive [28, 29]. Indeed, temporal change is noted as one of the ‘good things’ individuals notice about nature [16], with comfort and hope being gained through the regeneration of nature and involvement in the lifecycle of living organisms [25, 30].

Nature connectedness is positively associated with purpose in life through personal reflection on the importance of one’s place in the natural world and a sense of meaning from embracing the interconnectedness of nature [31]. It is therefore associated with Eudaimonic wellbeing (realizing one’s optimal potential) and promoting personal growth [32]. In this light, the optimum functioning gained from nature mirrors that of a flow-state in which the individual experiences self-transcendence from their total involvement in nature [28, 33].

1.2 Conservation and COVID-19

Nature connectedness is also important in conservation, with many conservation volunteers reporting a sense of connection with nature [34]. Indeed, Bragg’s [35] ‘ecological self’ and Clayton’s [36] ‘environmental identity’ highlight a sense of self that extends to form a collective identity with nature. Nature-connectedness offers a reciprocal relationship in which both the individual and the environment benefit, with regular engagement with the natural world resulting in pro-environmental behaviour [18].

In terms of conservation, volunteers’ experiences have varied throughout the pandemic, with some cancelling activities, and others gaining greater opportunities through permanently altered socio-economic states calling for a need to connect the public with nature [37]. For those who stopped volunteering, despite higher wellbeing scores prior to the pandemic, wellbeing was observed to decrease to the level of those who do not volunteer [38]. This dip could be an indication that reduced nature contact had a negative impact upon wellbeing in volunteers. Alternatively, it could be explained by reduced resilience to isolation as nature contact has been demonstrated to support wellbeing by combatting the negative psychological and physiological effects of social isolation [4]. Additionally, the pandemic caused stress to conservationists through the disruption of community projects and decreases in funding, creating concern for the survival of many conservancy organisations [39].

There is little research that addresses the experiences of nature volunteers during a time in which their access to nature was severely disrupted. The limited research which addresses this area is largely quantitative, focusing on associations and relationships between nature engagement and wellbeing or environmentalism rather than experiences [7, 40]. Given that research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic has centred on nature’s positive influence on public wellbeing and environmental concern [7, 41] further research is needed to understand how those who already had environmental concern coped with lockdown restrictions that limited their access to nature. Consequently, the current paper uses Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) to explore conservation volunteers’ experiences during the pandemic and the implications this held for wellbeing and environmental concerns.

2 Method

This study utilized Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) to gain detailed insight into conservation volunteers’ experiences with nature during the UK lockdowns which took place in 2020 (Table 1).

2.1 Participant information

Ten UK based participants whose volunteering in conservation had been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic were recruited in line with sampling guidelines for IPA by Smith et al. [42]. All participants responded to an advertisement about the study shared via email by their volunteering organizations. The sample included people aged between 24 and 71 years. All participants are white and the majority have tertiary qualifications.

2.2 Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants gave informed consent to take part in the study and were debriefed afterwards. In the interest of wellbeing, volunteers who were currently undergoing treatment for a clinical mental health condition or who had been hospitalized due to COVID-19 were not recruited.

The study complied with the British Psychological Society code of ethics and was approved on behalf of the University ethics committee (ETH2021-1849). Therefore the study met the required ethical guidelines and regulations. All participants are referred to using pseudonyms to protect their identities.

2.3 Data collection and analytic approach

All participants took part in a semi-structured interview facilitated by the first author via an online platform. Each interview began with general questions relating to the participants’ nature experiences pre-pandemic before progressing to discuss their experiences during the pandemic and the various UK lockdowns during 2020.

Interviews lasted between 45 and 90 min, were recorded, transcribed verbatim and analyzed using an IPA approach. Within IPA there is a focus on exploring participants’ experiences in detail [43]. Through examining a single phenomenon from multiple viewpoints, IPA allows for a detailed perspective of the studied phenomenon [44].

Analysis was guided by the procedure outlined by Smith et al. [42]. Each individual interview was read a number of times with initial notes being made to highlight any points of interest within each transcript. Next, Personal Experiential Statements (PES) were developed from patterns recorded in the data. Following this, connections between PES were explored and developed to create a set of Personal Experiential Themes (PET) for the case being studied. This process was then repeated across each case with Group Experiential Themes (GET) being developed for the whole cohort. Extracts which best represented the themes that were chosen for close analysis.

3 Results

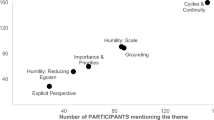

Three group experiential themes, outlined in Table 2, were developed during the analysis.

3.1 Sensations of nature

While engaging with nature, participants’ sensory experiences were key in accessing wellbeing benefits. Being able to tune into the present moment and experience the different sensations in the environment offered respite for the participants as well as providing the conditions for a deeper connection with nature. For some participants, this sense of presence in nature was something that required active investment.

I think being present in the moment really helps people connect to nature, because maybe they’re at the bottom of this two-thousand-year-old tree and to really take in the beauty of that, that’s something that I’m really trying to work on. I feel like I already appreciate nature but learning mindfulness has really helped me deepen that. (Corral)

Presence is required to really take in the beauty of an ancient tree and appreciate it more fully. Corral deepens her connection with nature through training her mind and her internal world to create the conditions required for presence. Her relationship with nature is dynamic as she puts in the effort to maintain and develop it. This shows how mindfulness and beauty, one of the pathways to nature connection, work together to foster a deep connection to nature [21, 22]. For other participants, the external environment led to a sense of presence.

I guess the quiet, the beauty of nature, the - you know, just completely different environment from the usual bustling city, our kind of busy lives that we all kind of have right now. It’s just that - brings a sense of calm and it kind of allows me to just be with myself if that makes sense? and forget every negative thing that’s going on (Sharon).

Sharon focuses on how the quiet and beauty of nature brings a sense of presence and places this in sharp contrast with the bustling city. Natural environments are conceptualised as a space of welcome solitude in which Sharon can focus her attention inwards, connect with herself, and feel a sense of calm. Furthermore, Sharon’s experience of presence is quite different to that of Corral’s who describes it as a form of escapism, providing relief from the stress of modern life. Furthermore, Sharon’s focus lies in how the natural environment creates a sense of presence and a calm mind in contrast to Corral’s effort in cultivating the mind to deepen a sense of connection and presence with the external, natural world. This exemplifies aspects of ART and sheds light upon how distance from fatiguing activities is embodied in personal experience. Sharon’s experience of nature as a place of sanctuary was shared by other participants too and took on a special significance during the COVID-19 pandemic.

During like this current time everything is very stressful, very scary being just on your own and being able to, like, breathe fresh air just feels very relaxing and soothing (Emma)

Emma turned to nature during the pandemic to relax and escape the stress and uncertainty in her life. The sensation of breathing fresh air enables her to tune into the present moment, taking her out of the worry she feels in her everyday environment and, in a similar way to Sharon, allows her to focus on her sense of self and the calmness of the moment. The environment is literally and figuratively a breath of fresh air, providing her with comfort and respite from stress. This further explores the relevance of ART in terms of compatibility of needs through being a space she can rely on to provide her with the conditions she needs to feel calm during moments of stress.

Within the interviews, the experience of presence was closely aligned with sensory experiences. For many participants, there was a feeling of oneness with the sensations of nature.

You can feel the breeze and the sun on you and hear the birds singing and you just feel more at one with everything and it just. It just feels calming and nice and when you’re out in the garden - in your own gardens - and things and you’re just pottering, planting things. Time just passes by so quickly. (Janet)

The calm that participants experienced through a sense of presence in nature is explored further here. The sensory experiences Janet feels in nature move beyond an exclusive focus on wellbeing towards being at one with nature. This builds upon experimentally based research which has demonstrated the calming effect of nature sensations by demonstrating the link that these sensations have for developing an ecological sense of self [35, 36]. This connection transcends wellbeing and enables Janet to experience a reciprocal relationship with nature centred on gardening. Furthermore, Janet is taken into a state of flow, in which she loses herself to the environment and the work she is doing. This all-encompassing feeling described by Janet is linked to her garden which holds a different sensory experience to the everyday urban environment. It also enables her to experience the beneficial effects of nature through engagement with simple activities—such as listening to birdsong [45]—that involve us actively noticing nature and tuning in, rather than simply spending time in it [46].

This theme explored how the sensations of nature were central to well-being and builds upon previous research by demonstrating how these sensations cultivate a deeper connection to nature. The sensory experience of nature was central to promoting mindfulness and a sense of presence which amplified a sense of wellbeing. Therefore, the analysis has demonstrated how ART, mindfulness and sensory experiences all work together to mediate the relationship between wellbeing and nature connection.

3.2 Stability from nature

Within the interviews, the participants found stability from the deeper meaning they found in nature. Witnessing the continuation of nature through the seasons and years brought feelings of contentment, comfort and hope for the future. Finding meaning in nature extended the participants’ awareness and provided a sense of perspective.

I feel very content and it just you know it puts everything into perspective really because when you're out in nature you realize that your minor, little worries aren’t really that important (Adam)

When describing a sense of contentment, the meaning Adam derives from nature is informed by a sense of perspective from placing himself in the natural world. There is a sense that nature is viewed as greater than himself and Adam places himself outside of his own individual experiences and turns his focus towards a wider experience of life [47]. This evokes an understanding of Adam’s own place in nature and a shift of perspective from a narrow individualistic view to one that is wider and more collective. This wider view of nature is further expanded by Corral.

Definitely a feeling of calm and belonging and just being at ease, um I guess that’s where we came from and some of us are starting to tune into what our ancestral bodies are wanting (Corral)

The sense of calm that Corral established through her engagement with nature allows her to feel at home in the natural world. The word belonging describes a sense of comfort and suggests that she feels the natural world reflects her own inner being. Corral recognizes that she is a part of nature, and through this can tune into her evolutionary past, listening to the way her body and mind respond to nature and nourishing the ancestral need for proximity to nature rather than creating further separation from her evolutionary roots.

For some participants, a sense of stability and meaning was found in the sub theme continuation of nature.

I just admire the beauty of trees and leaves and it - no matter what time of year really, even a bare tree is beautiful to me. It’s the shapes and everything and um I think you just get a feeling you know this has been here for a very long time these trees are gonna go on forever probably long after me and it’s just that feeling of sort of stability. (Singing Leopard)

Singing Leopard’s admiration of trees extends beyond their physical beauty, with the longevity that they represent being a source of meaning for her. In this light, Singing Leopard gains a sense of stability from observing the regeneration of nature, evoking a sense of contentment with her position in nature and an understanding of the temporal nature of life. The idea that trees will continue to live forever reassures Singing Leopard of her own passing, understanding that although she is no longer present, nature will continue. Janet also discussed the importance of this sense of stability.

It’s just always there and I find that comforting because whatever happens you can look outside and see a plant, or a flower and it just affirms that everything’s alright. (Janet)

Where Singing Leopard gained stability in the passing and regeneration of nature, Janet gains stability from the perpetual nature of plants. With this, nature is a companion to Janet, offering the reassurance that everything’s alright. Nature is a continuing source of support for her, as although uncertainty pervades modern life, nature is one thing which she can always rely on to give her the affirmation she is looking for.

I find the seasons and during the first lockdown how quickly it moved back in giving hope there really for the future and you know you heard increase birdsong animal activity. You very quickly got animals coming in and birds coming into quite built-up areas (David)

David’s appreciation of the seasons gave him a sense of hope for the future during the COVID-19 pandemic. The way in which the seasons moved back in during the pandemic brought this sense of hope in terms of personal regeneration signifying to David that as the seasons disappear and reappear each year, he too will pass through this time of hardship and come out the other side anew. David also found hope in the migration of animals into habitats where they would not previously have been seen, offering him an optimistic outlook for the future both in terms of humans eventually returning to the habitats they have currently lost through lockdown, and the potential for nature to recover from reduced human interference.

This theme explored the ways in which stability can be gained through finding meaning in nature and from its continuation. The meaning participants gained from nature ranged from an increased perspective of one’s place in nature, to finding a sense of belonging in the environment. This illustrates the ways in which the ecological self or environmental identity can be experienced as within the participant accounts there was a sense a of deep-rooted connection to nature which was rooted in a shared human ancestry. Stability can be observed in the sense of contentment and belonging participants found through these experiences. Participants' experiences of the continuation of nature expanded on this sense of meaning allowing for a feeling of acceptance around the temporal nature of life, a sense of comfort in the ever-presence of nature and a sense of hope for the future through nature’s regeneration. This showed how connection to nature through meaning mediated well-being and how total involvement in nature supported eudemonic well-being.

3.3 Changing relationships with nature

Through volunteering and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, participants experienced a change in focus from wellbeing to environmental concern. This theme discusses an increased sense of awareness of the issues in nature and a desire to protect and give back to nature. Volunteers gained a greater awareness of nature from connecting with it in their own work and through the COVID-19 pandemic.

You can see the decline or if in some areas that it’s getting better and that you could come back and be like ‘wow this is so much better than it was last year’. Be that just because people have intervened and helped or quite the opposite people have stopped coming there due to the pandemic, nature being able to thrive without them there. (Geoff)

Geoff became more attuned to his environment, noticing how a lack of human involvement had shaped the landscape for better or worse. There is a sense of optimism in Geoff’s discovery of nature’s recovery, with the visible changes in the environment allowing him to reflect on the different ways in which nature has benefitted from the pandemic. Tension can be observed between human intervention, which has helped nature and how nature has thrived without people. Observing the way in which nature had been given a respite to grow at its own pace without being restricted has prompted Geoff to reflect upon the human-nature relationship and the ways in which this needs to be managed to support the natural environment. This increased sense of awareness was also shared by other participants.

It’s made me more aware - because I’ve got to spend more time in it - of the things that are locally really important. For example, going on a walk, we found a new area that was being affected by ash die-back, which is a tree disease and that’s not really something that I thought was locally relevant until I really had time to read signs and have a look. So yeah it’s definitely making me more aware of ways I can volunteer (Corral)

Corral’s more frequent visits to local nature during lockdown encouraged reflection on the health of nearby nature. Where Geoff reflected on the changes in the environment from reduced human interference with nature, Corral has become more aware of previously existing issues within the environment which had previously been neglected. This inspired Corral to consider the ways in which she can take her volunteering in the future. In contrast to Geoff, human intervention is presented as important in maintaining local health. Nature is fragile and requires nurturance to thrive.

For some participants, this greater awareness of environmental issues during the pandemic inspired a desire to give back to nature.

The pandemic doesn’t care if you know this wildlife sanctuary needs volunteers to make sure the animals are ok and you know it doesn’t. Just cause the pandemic stops our daily lives it doesn’t stop the daily lives of marine animals or wildlife (Sharon)

Sharon evokes a sense of urgency to help nature during the pandemic. Personifying the pandemic as cold and uncaring Sharon emphasizes its threat to nature, presenting a need for human intervention to protect nature from a pandemic. In this way, Sharon displays a sense of guardianship over the animals she works with and a need to stand up for those who cannot stand up for themselves. The pandemic conceptualized as an enemy to both humans and nature, with a wider view towards the damage that the pandemic causes. This sense of need to fight for nature is further explored by Singing Leopard.

We just got to take action now haven’t we? We can’t let things slip for many more years really and if younger people get involved yeah hopefully will inject some new energy in - into the fight (Singing Leopard)

Singing Leopard demonstrates an urgency to act now, suggesting that the planet’s well-being is a priority and humans should work together to prevent its decline. Singing Leopard implies that this is a collective issue and is something that without the investment of the whole of humanity, cannot be achieved. There is much hope for the younger generation, whose fresh perspective on the issue will provide new energy to tackle nature's decline. This endeavour is described as the fight, which in a similar way to Sharon, reinforces that nature is something that needs to be stood up for, implying a sense of rebellion against an oppressive force which is leading to the decline of nature. This sense of protection over nature is explored in a practical sense by Jenny.

I think also my desire to protect it more and to help connect people with nature more. Not in the way that necessarily I think is right, but like the way that is sort of more about conservation (Jenny)

Building on the perspective of Singing Leopard, Jenny suggests how individuals can best protect nature. For Jenny, protecting nature starts with connecting individuals with nature. While Singing Leopard and Sharon express passion to stand up and fight for nature, Jenny understands the need to create connections between people and nature centering on conservation for nature to be protected. Despite this, for Jenny this type of connection is not what she believes is right, implying that she would like to connect individuals with nature in a way which holds personal meaning to them. However, considering the pandemic, and environmental decline, Jenny notices the need for this type of connection to take a back seat while the focus shifts towards the needs of nature rather than the needs of the individual.

Time spent in local nature both before and during the pandemic led to reflection upon the impact that humans have on their environment. For some volunteers, there was an acknowledgement of how a lack of human activity provides nature with respite and the ability to grow without restriction. For others, it highlighted the role humans have in protecting nature and the need to move the focus of connecting with nature away from primarily focusing on wellbeing and becoming more inclusive of environmentalism.

4 Discussion

This analysis has explored UK-based conservation volunteers’ nature experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and the implications this had for wellbeing and environmental concern. Although the findings cannot be widely generalized, the analysis raises important issues about the ways in which nature volunteers engaged with nature during the pandemic and how nature supported human wellbeing, cultivated an increased awareness of environmental issues and a desire to look after the natural world. The findings contribute to quantitative research that has established a relationship between sensations of nature and wellbeing and ART theory which explains the how a sense of wellbeing is achieved through nature connection. By paying attention to participants' experiences, the analysis has exemplified how the relationships evidenced in the literature are embodied and their meaning for people. It also attends to the interplay between theories and how a relationship to nature which supports wellbeing and environmental concern is mediated.

Within the analysis, sensory engagement with nature provided respite in people’s daily lives and cultivated a sense of peace and tranquility [15]. This is important as it aligns closely with the Attention restoration theory [12] and further evidences how the senses enable people to experience clear-mindedness and gives them an escape from the demands of everyday life. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this held particular relevance, as nature became a place of refuge; not only from daily stressors, but the greater threat of a global emergency. Therefore, our analysis exemplifies concepts that are central to ART but are often criticised for being vague such as compatibility with needs [48] and demonstrates how this is presented within individuals' everyday experiences.

Therefore, our analysis exemplifies concepts that are central to ART, such as compatibly with needs, and demonstrated what these concepts mean for everyday experience. This is important for furthering understanding of ART as this theory has been criticized for not defining core concepts clearly enough. Furthermore, the analysis demonstrated the links between sensory engagement and ART. This extends the literature that used experimental approaches to establish a link between sensory experiences and wellbeing by demonstrating how a sense of wellbeing was brought about through engaging with the senses and the role that ART had in mediating this experience [12,13,14].

Sensory engagement also created a deeper sense of connection with nature which evoked a feeling of oneness with the environment. The implications of this are twofold. First, it illustrates the ways that this engagement with nature moved beyond the sense of calm established in the literature as sensory experiences were key to developing an ecological sense of self [35, 36]. Within this the participants were one with nature and a deep connection was established. This was nurtured through activities such as gardening which created a sense of flow [33]. This highlights the interplay between the sensations of nature, mindfulness, ART and demonstrates how these concepts work together to promote personal well-being and a sense of being at one with nature. It also builds upon the literature that links sensory experiences with wellbeing by demonstrating that sensory experiences are also key to developing a sense of self that incorporates nature.

The sense of interconnectedness participants gained through engaging with nature mindfully offered a sense of perspective, reassurance, stability and hope. There was a shift in perspective from an individualistic view to a collective understanding of one’s place in nature. This was associated with a feeling of belonging as nature was seen as a link to human’s evolutionary past. Nature was also seen as a window to the future, with the seasonal regeneration of nature providing a sense of stability through a realisation that nature will continue long after humans have passed [25]. Consequently, nature evoked a deeper sense of meaning, allowing for a sense of comfort in and acceptance of the temporality of life [25]. During the COVID-19 pandemic the continuation of nature had particular value. It provided a sense of hope for human’s reintegration into spaces that had been lost during the pandemic, as well as for the future of nature, with nature’s recovery during the lockdown periods providing hope for nature’s future recovery from human activity. Thus, the analysis adds to the experimental literature which has established a relationship between nature engagement and wellbeing by exploring the role that finding meaning in nature and Eudaimonic wellbeing has in supporting this relationship. Indeed, connection to nature gave the participants a sense of perspective and an opportunity for personal growth.

During the UK lockdowns, the participants’ connection with nature and increased time spent in locally accessible nature. This is significant as it indicates a shift in the type of nature that volunteers engaged with. As already established mundane nature became important for supporting wellbeing and enabling the participants to cope with the demands of lockdown. However, mundane nature also played an important part in creating heightened environmental awareness. With this, conflict was observed between the benefits of people intervening with nature and the improvements that had emerged from lower public visitation. Mirroring research from Corlett et al. [37] and Smith et al. [39] it was observed that free from human interference nature was allowed to rejuvenate and this led to an understanding of the damage humans can cause nature. However, for some participants visits to local nature drew attention to issues that had gone unnoticed before and this highlighted volunteer opportunities. Therefore, mindfulness was beneficial for the individual and the environment, with mindful attention in nature leading to greater awareness of one’s surroundings and deep reflection on the human nature relationship which extended beyond their personal connection to encompass the role that humanity has in damaging and protecting nature. Furthermore, these changes highlighted the role that mundane nature plays in bringing about positive change. This implies that easily accessible sites of mundane nature are important both in terms of supporting wellbeing in a post covid landscape and for enabling people to foster a sense of environmental concern.

This demonstrated the need for a wider worldview in which humans consider the needs of wildlife and no longer view themselves above nature [23]. With this, a sense of needing to fight for nature was expressed with climate change and the pandemic being seen as a collective threat. In line with this, importance was placed on creating a human-nature relationship in which conservation is placed at the centre.

5 Conclusion

Findings presented in the analysis provided support for ART through highlighting the influence of sensory engagement on respite from stress and a sense of clear-mindedness, calmness, and flow-state. Different types of nature evoked different responses from the environment, with mundane nature particularly having benefit for maintaining wellbeing and environmental concern at a time when volunteering was disrupted. Mundane nature shows potential for interventions as we move through post covid recovery, with greater access to local nature supporting wellbeing and leading to greater concern for the environment. Indeed, research that investigates public engagement with mundane nature is needed to deepen understanding of this area.

Data availability

The full data set utilized in this study—both recordings of interview and the transcripts of interviews—cannot be shared. When giving informed consent to participate in the study participants gave consent for their interviews to be stored securely and anonymously and to be only accessed by the authors of the research for the purposes of analysis.

References

Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O’neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020;1(76):71–6.

Saadat S, Rawtani D, Hussain CM. Environmental perspective of COVID-19. Sci Total Environ. 2020;1(728): 138870.

White RG, Van Der Boor C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and initial period of lockdown on the mental health and well-being of adults in the UK. BJPsych open. 2020;6(5): e90.

Samuelsson K, Barthel S, Colding J, Macassa G, Giusti M. Urban nature as a source of resilience during social distancing amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

Venter ZS, Barton DN, Gundersen V, Figari H, Nowell M. Urban nature in a time of crisis: recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environ Res Lett. 2020;15(10): 104075.

Pouso S, Borja Á, Fleming LE, Gómez-Baggethun E, White MP, Uyarra MC. Contact with blue-green spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown beneficial for mental health. Sci Total Environ. 2021;20(756): 143984.

Severo EA, De Guimarães JC, Dellarmelin ML. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on environmental awareness, sustainable consumption and social responsibility: evidence from generations in Brazil and Portugal. J Clean Prod. 2021;1(286): 124947.

Shreedhar G, Mourato S. Linking human destruction of nature to COVID-19 increases support for wildlife conservation policies. Environ Resour Econ. 2020;76(4):963–99.

Ammendolia J, Saturno J, Brooks AL, Jacobs S, Jambeck JR. An emerging source of plastic pollution: environmental presence of plastic personal protective equipment (PPE) debris related to COVID-19 in a metropolitan city. Environ Pollut. 2021;15(269): 116160.

Thompson CW. Linking landscape and health: the recurring theme. Landsc Urban Plan. 2011;99(3–4):187–95.

Wood L, Hooper P, Foster S, Bull F. Public green spaces and positive mental health–investigating the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental wellbeing. Health Place. 2017;1(48):63–71.

Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol. 1995;15(3):169–82.

Qiu M, Sha J, Utomo S. Listening to forests: comparing the perceived restorative characteristics of natural soundscapes before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2020;13(1):293.

Koga K, Iwasaki Y. Psychological and physiological effect in humans of touching plant foliage-using the semantic differential method and cerebral activity as indicators. J Physiol Anthropol. 2013;32(1):1–9.

Dzhambov AM, Lercher P, Browning MH, Stoyanov D, Petrova N, Novakov S, Dimitrova DD. Does greenery experienced indoors and outdoors provide an escape and support mental health during the COVID-19 quarantine? Environ Res. 2021;1(196): 110420.

Richardson M, Hallam J, Lumber R. One thousand good things in nature: aspects of nearby nature associated with improved connection to nature. Environ Values. 2015;24(5):603–19.

Mayer FS, Frantz CM. The connectedness to nature scale: a measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J Environ Psychol. 2004;24(4):503–15.

Nisbet EK, Zelenski JM, Murphy SA. The nature relatedness scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environ Behav. 2009;41(5):715–40.

Howell AJ, Dopko RL, Passmore HA, Buro K. Nature connectedness: associations with well-being and mindfulness. Personality Individ Differ. 2011;51(2):166–71.

Hamann GA, Ivtzan I. 30 minutes in nature a day can increase mood, well-being, meaning in life and mindfulness: Effects of a pilot programme.

Van Gordon W, Shonin E, Richardson M. Mindfulness and nature. Mindfulness. 2018;9(5):1655–8.

Lumber R, Richardson M, Sheffield D. Beyond knowing nature: contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5): e0177186.

Howell AJ, Passmore HA, Buro K. Meaning in nature: meaning in life as a mediator of the relationship between nature connectedness and well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2013;14:1681–96.

Baumeister RF. Meanings of life. New York: Guilford press; 1991.

Passmore HA, Howell AJ. Eco-existential positive psychology: experiences in nature, existential anxieties, and well-being. Hum Psychol. 2014;42(4):370–88.

Lee-Hammond L. Belonging in nature: spirituality, indigenous cultures and biophilia. International handbook of outdoor play and learning. 2017:319-32

Berkes F. Sacred ecology. London: Routledge; 2017.

Almaas AH. Essence with the elixir of enlightenment: the diamond approach to inner realization. Newburyport: Weiser Books; 1998.

Davis J. The transpersonal dimensions of ecopsychology: nature, nonduality, and spiritual practice. Hum Psychol. 1998;26(1–3):69–100.

Unruh A, Hutchinson S. Embedded spirituality: gardening in daily life and stressful life experiences. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25(3):567–74.

Nisbet EK, Zelenski JM, Murphy SA. Happiness is in our nature: exploring nature relatedness as a contributor to subjective well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2011;12:303–22.

Trigwell JL, Francis AJ, Bagot KL. Nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: spirituality as a potential mediator. Ecopsychology. 2014;6(4):241–51.

Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow. The psychology of optimal experience. New York: HarperPerennial; 1990.

Guiney MS, Oberhauser KS. Conservation volunteers’ connection to nature. Ecopsychology. 2009;1(4):187–97.

Bragg EA. Towards ecological self: deep ecology meets constructionist self-theory. J Environ Psychol. 1996;16(2):93–108.

Clayton S. Environmental identity: a conceptual and an operational definition. Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature. 2003:45–65

Corlett RT, Primack RB, Devictor V, Maas B, Goswami VR, Bates AE, Koh LP, Regan TJ, Loyola R, Pakeman RJ, Cumming GS. Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on biodiversity conservation. Biol Cons. 2020;1(246): 108571.

Biddle N, Gray M. The experience of volunteers during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lendelvo SM. A perfect storm? The impact of COVID-19 on community-based conservation in Namibia.

Kou H, Zhang S, Li W, Liu Y. Participatory action research on the impact of community gardening in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: investigating the seeding plan in Shanghai, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6243.

Smith MK, Smit IP, Swemmer LK, Mokhatla MM, Freitag S, Roux DJ, Dziba L. Sustainability of protected areas: vulnerabilities and opportunities as revealed by COVID-19 in a national park management agency. Biol Cons. 2021;1(255): 108985.

Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin, M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method and research. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. 2021:1–00

Smith JA, Eatough V. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: lyons E, Coyle A. Analysing qualitative data in psychology. 2007:35–64.

Reid K, Flowers P, Larkin M. Exploring lived experience. Psychologist. 2005;18(1):20–3.

Richardson M, Passmore HA, Lumber R, Thomas R, Hunt A. Moments, not minutes: the nature-wellbeing relationship. Int J Wellbeing. 2021;11(1):8–33.

Richardson M, Hamlin I, Butler CW, Thomas R, Hunt A. Actively noticing nature (not just time in nature) helps promote nature connectedness. Ecopsychology. 2022;14(1):8–16.

Gould RK, Merrylees E, Hackenburg D, Marquina T. “My place in the grand scheme of things”: perspective from nature and sustainability science. Sustain Sci. 2023;6:1–7.

Joye Y, Dewitte S. Nature’s broken path to restoration. A critical look at Attention Restoration Theory. J Environ Psychol. 2018;59:1–8.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the volunteers who participated in the study for sharing their experiences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rhys Furlong: Conceptualisation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology and writing original draft. Jenny Hallam: Conceptualisation, formal analysis, methodology, supervision and writing (review and editing). Christopher Barnes: Conceptualisation,, supervision and writing (review and editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All authors confirm that that they have no conflicting interests. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. All participants gave informed consent to take part in the study and were debriefed afterwards. In the interest of wellbeing, volunteers who were currently undergoing treatment for a clinical mental health condition or who had been hospitalized due to COVID-19 were not recruited. The study complied with the British Psychological Society code of ethics and was approved on behalf of the University ethics committee (ETH2021-1849). All participants are referred to using pseudonyms to protect their identities.

Competing interests

Rhys Furlong: No conflict of interest. Jenny Hallam: No conflict of interest. Christopher Barnes: No conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Furlong, R., Hallam, J. & Barnes, C. Conservation volunteers’ experiences of connecting with nature during the COVID-19 pandemic: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Discov Psychol 4, 30 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00144-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00144-3