Abstract

Background

BMI has been reported to be a major risk factor for the increased burden of several diseases. This study explores the burden of cancer linked to high body mass index (BMI) in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and assesses the correlation with Socio-demographic Index (SDI).

Method

Using Global burden of disease (GBD) 2019 data, the authors quantified cancer burden through mortality, DALYs, age standardized mortality rate (ASMR), and age standardized DALYs rate (ASDR) across sexes, countries, cancer types, and years. Spearman’s correlation tested ASMR against SDI. The authors estimated 95% uncertainty limits (UIs) for population attribution fraction (PAFs).

Results

Between 1990 and 2019, all six GCC countries showed increased number of the overall cancer-related deaths (398.73% in Bahrain to 1404.25% in United Arab Emirates), and DALYs (347.38% in Kuwait, to 1479.35% in United Arab Emirates) reflecting significant increasing in deaths, and burden cancer attributed to high BMI. In 2019, across GCC countries, pancreatic, uterine, and kidney cancer accounted for 87.91% of the total attributable deaths associated with high BMI in females, whereas in male, colon and rectum cancer alone accounted for 26% of all attributable deaths associated with high BMI.

Conclusion

The study highlights the significant impact of high BMI on cancer burden in GCC countries. Moreover, the study identifies specific cancers, such as pancreatic, uterine, and kidney cancer in females, and colon and rectum cancer in males, as major contributors to attributable deaths, urging targeted prevention strategies at reducing weight and encouraging physical activity could greatly lessen the impact of diseases in the GCC countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

High body mass index (BMI), defined as 25 kg/m² or greater, is a complex risk factor with significant implications for public health [1]. It substantially elevates the risk of various health complications, making it a focal point in public health discussions. Obesity, a consequence of high BMI, is firmly established as a risk factor for numerous chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and specific types of cancer [2–3]. The global surge in overweight and obesity rates can be attributed mainly to lifestyle shifts stemming from societal and demographic transitions that unfolded over the past few decades. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, oil-producing nations, have experienced profound lifestyle changes due to rapid economic and demographic transformations. Furthermore, the influence of a Westernized lifestyle has permeated these countries, leading to shifts in dietary habits characterized by increased consumption of processed and high-fat foods [4]. These societal shifts have contributed significantly to the rising prevalence of obesity in the GCC countries, highlighting the urgency of addressing this public health challenge.

BMI has been reported to be a major risk factor for the increased burden of disease in 2013 in Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and Saudi Arabia [5]. Consistently, High BMI ranked first risk factor associated with many diseases over the period 1990–2017 in Saudi Arabia [6]. Furthermore, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Qatar were among the top ten countries with the highest prevalence of obesity worldwide in 2013 and 2019 [7–8]. On the other hand, cancer ranked as the third leading cause of death and premature disability attributable to high BMI worldwide; it is challenging healthcare systems and communities globally [1]. The GCC countries are no exception to this global trend, as they face a rising incidence of cancer and its far-reaching consequences [9–10]. High BMI is not a benign condition; in recent years, research has underscored its role in cancer development and progression. The relationship between high BMI and cancer has been well-documented in the literature [11]. Excess body weight has been implicated in the development of several types of cancer, including breast, colorectal, and endometrial cancer [12,13,14] The mechanisms of this relationship are multifaceted, involving metabolic, hormonal, and inflammatory pathways. In essence, high BMI creates an environment within the body that fosters the initiation and progression of cancer cells [11, 15, 16].

According to recent studies [11]; 4 to 8% o cancer cases are attributable to excess body weight. Other studies indicate that each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI was positively associated with cancers of the uterus, gallbladder, kidney, cervix, thyroid, and leukemia [17]. Despite the escalating rates of obesity and its well-established association with various cancers, there is a scarcity of region-specific data exploring cancer attributable to high BMI in the GCC countries [18,19,20]. Nonetheless, prevalence and impact vary across countries and populations, including gender-based variations. Cancer cases increased by 136% from 1999 to 2015 and are projected to rise by 63% in 2030 in Saudi Arabia [21]. As obesity and cancer rates continue to rise in the GCC countries, research in this domain becomes a basis for identification and mitigation of preventable risk factors for these carcinomas becomes paramount, mitigating the burden of obesity-related cancers, and promoting overall well-being in the region. Therefore, this study aims to utilize data obtained from GBD, to estimate the burden of cancer related death and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) attributable to high BMI for GCC countries between 1990 and 2019 using the latest GBD 2019 dataset. Additionally, the authors assessed the correlation between cancer burden and Socio-demographic Index (SDI). The long-term trends of the age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) were also analyzed. The main objective of this study was to utilize the data and their fluctuations to guide potential strategies in primary prevention, screening, early detection, and treatment of cancer linked to high BMI.

2 Method

2.1 Data Source & Search Parameter

In this population-based epidemiological study, the authors used GBD’s 2019. The GBDs consisted of multiple measures of health loss for 282 causes of death, 359 diseases, and 84 risk factors for each of 204 countries and territories, 23 age groups, and both sexes from 1990 to 2019 [22]. The GBD 2019 study obtained data from several data sources, including national vital statistics, cancer registries, verbal autopsy reports, national health surveys, censuses, and published studies. The authors quantified the burden of cancer attributable to high BMI from 1990 to 2019. The interested data were collected from the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) tool (https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019) and selected “neoplasm and specific cancer types” as the cause, and “high BMI” for risk; “deaths, DALYs” for measurements “1990–2019” for years; and “number and rate” for metrics. Data were downloaded at both sex, SDI, and GCC country levels. We obtained data at all ages and age-adjusted categories.

2.2 Definitions

This study focused on high-risk populations with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 and higher aged 20 years or older in high-income GCC countries in the Middle East. The GCC comprises of six countries; Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab of Emirates located in southwest Asia. In 2012 the GCC had a more than 57 million population. They share similar political, religious, cultural, economic, and social backgrounds.

In this study the authors included cancers that have significant evidence associated with high BMI reported by the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) [23]. Cancer presented in this study includes malignant neoplasms defined by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD) by the Tenth Revision (ICD-10) as codes esophageal (C15-C15.9, D00.1, D13.0) colon and rectal(C18-C21.9, D01.0-D01.3, D12-D12.9, D37.3-D37.5), kidney (C64-C65.9, D30.0-D30.1, D41.0-D41.1), pancreatic (C25-C25.9, D13.6-D13.7), gallbladder (C23-C24.9, D13.5), breast (C50-C50.9, D05-D05.9, D24-D24.9, D48.6, D49.3), uterine (C54-C54.9, D07.0-D07.2, D26.1-D26.9), ovarian cancers (C56-C56.9, D27-D27.9, D39.1) and liver cancer (C22-C22.8, D13.4). Also, the authors included additional cancer sites that have recently been suggested to be associated with high BMI but were not listed by WCRF as sufficient [24,25,26]. This includes thyroid cancer (C73-C73.9, D09.3, D09.8, D34-D34.9, D44.0), Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (C82-C86.6, C96-C96.9), Multiple myeloma (C88-C90.9), and Leukemia (C91-C91.0, C91.2-C91.3, C91.6, C92-C92.6, C93-C93.1, C93.3, C93.8, C94-C95.9). The authors calculated the incidences of these cancer subtypes utilizing proportions by sex and country level. The exact time interval between the onset and duration of elevated BMI and the manifestation of cancer remains uncertain.

The DALYs is a summary measure that quantifies the overall burden of disease, which represents the sum of years of life lost due to premature death (YLL) and years lived with disability (YLD). One DALY can be regarded as the loss of 1 year in total health [22]. The Socio-demographic Index (SDI) is calculated by GBD study 2019 as a measurement of overall development covering educational level, distributed income, and total fertility rate [27]. The SDI ranges from 0 to 1, with a higher value implying a higher level of socioeconomic development. high SDI (> 0.81), high-middle SDI (0.70 – 0.81), middle SDI (0.61–0.69), low-middle SDI (0.46–0.60), and low SDI (< 0.46).

2.3 Statistical Analysis

The burden estimates are presented regarding the numbers of DALYs, and deaths. ASMR and age standardized DALYs rate (ASDR) are expressed as the rate per 100,000 people. The ASMR and the ASDR were used to quantify the burden of cancer associated with BMI. The attributable fraction of cancer specific incidence, deaths and DALYs related to high BMI was measured using the Population Attributable Fraction (PAF). This is defined as the proportion of all cases of a specific disease or other adverse condition in a population that can be attributed to a particular risk factor.

The PAF of ASDR, incidence and deaths of each cancer due to high BMI was employed to estimate the burden of high BMI, broken down by country, age group, sex, and year. In GBD 2019, the Theoretical Minimum Risk Exposure Level (TMREL) was used to determine the level of exposure to high BMI that would minimize the risk of DALYs and deaths of each type of cancer. This was done by measuring the estimated relative risk (RR) of DALYs and deaths of each cancer due to high BMI. The methods used to estimate the disease burdens, and the impact of risk factors have been extensively described in previous publications [28–22].

The following formula was used to calculate the PAF:

n is the lowest level of exposure observed, m is the highest level of exposure recorded, RR(x) is the relative risk at an exposure level of x and P(x) is the fraction of risk exposure.

We used the GBD estimated 95% uncertainty limits (UIs) for PAFs, and their trends or changes from 1990 to 2019 and analyzed mortality and DALYs descriptively by gender, country, cancer types, year, and then plotted the temporal trends of annual percentage change measures from 1990 to 2019 calculated by GBDs 2019. Finally, Spearman’s correlation test was used to examine the relationship between SDI and the ASMR of cancer attributable to high BMI in 2019 by location and year. Significance level was set at a p-value of ≤ 0.05 and 95% CI. Collected data were entered and analyzed with SAS 9.4. Detailed methods of data on high BMI, and calculation of mortality and DALYs have been reported in previous studies by GBD collaborators [22].

3 Results

3.1 Deaths and DALYs of Cancer Attributable to High BMI from 1990 to 2019 for both Sexes in GCC Countries

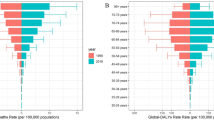

Between 1990 and 2019, all six GCC countries showed an increased number of overall cancer-related deaths increase (range between 398.73% in Bahrain to 1404.25% in United Arab Emirates), and DALYs (range 347.38% in Kuwait, to 1479.35% in the United Arab Emirates) reflecting significant increasing mortality burden cancer attributed to high BMI (Table 1). Overall, while each country showed different patterns and trajectories in disease burden and mortality rates, there were consistent disparities between sexes, with males generally experiencing higher rates of disease burden and mortality compared to females. These gender disparities were evident across various health indicators, including DALYs, ASDR, and the number of deaths. The GCC country’s cancer-related deaths attributable to high BMI have increased from 174.96 in 1990 to 1520.99 in 2019 for males and have increased from 134.19 in 1990 to 689.4 in 2019 for females (Table 1). Among the countries studied, United Arab Emirates showed the highest increase in the number of DALYs, with an overall percentage increase of 1479.35, driven primarily by a substantial increase in DALYs among males (1789.8%). Oman demonstrated the highest increase in the ASDR per 100,000 population, with a remarkable 152.16% percentage increase overall and a significant increase among males (178.77%) (Table 1; Fig. 1). Regarding overall changes in mortality rates, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar showed the highest percentage change in the number of deaths, with a remarkable increase of 1404.25%, and 813.82% respectively. This increase was predominantly observed among males (United Arab Emirates 1762.24%, Qatar 935.31%), highlighting a concerning trend in mortality rates in the region. The highest increase in ASMR was in Oman with 186.25% percentage increase largely driven by the increase in ASMR among males with 225.24% percentage increase (Table 1).

3.2 Percentage Change from 1990 to 2019 in DALYs, and Death of Cancer Attributable to High BMI by GCC Countries, Both Sexes, and Cancer Types

In Table 2, the highest increases in the number of deaths and DALYs for both sexes across all countries were observed for pancreatic cancer (ranged between 6 and 33 times higher than baseline), kidney cancer (ranged between 6 and 12 times higher than baseline), ovarian cancer (ranged between 3 and 17 times higher than baseline), and colon and rectum cancer (ranged between 3 and 12 times higher than baseline). When adjusting for age, pancreatic cancer, kidney cancer, and colon and rectum cancer exhibited the highest increases in ASMR and ASDR among all included countries (Table 2). Notably, the most substantial percentage increase occurred in pancreatic cancer in the United Arab Emirates, with a remarkable surge of 3261%, which translates to approximately 33.61 times higher than the baseline (Table 2).

3.3 Temporal Trends of Deaths, DALY’s ASDR and ASMR Between the Years 1990 to 2019

In 2019, there were more than 2,210 thousand (2.16%) deaths can be attributed to high BMI, corresponding to an ASMR of 59.96 per 100,000. DALYs resulting from cancer were estimated to be 322,168 thousand, of which 1.28% (4152 thousand) was attributed to high BMI, with an ASDR of 133.93 per 100,000. The time trend showed a consistent upward trend of death numbers, DALYs, ASDR, and ASMR between the years 1990 and 2019 in all GCC countries except for Bahrain, which (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 3 A, and B). The United Arab Emirates had a more than 14-folded increase in the death rate and a nearly 15-folded increase in DALYs. Whereas, Qatar had nearly 8-foldeed increase in death, and 8-folded increase of DALY’s of cancer attributable to high BMI between the 1990 to 2019 (Supplementary Table 3 A). The ASDR and ASMR of cancer attributable to high BMI trend increase (ranging between 30 and 90% increase) were the highest in the United Arab of Emirates and Qatar rate between the years 1990 to 2019 compared to other GCC countries. (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 3B).

3.4 DALYs and Deaths of Specific Cancer Types Attributable to High BMI in 2019 and Percentage Change from 1990 to 2019 by Cancer Types and GCC Countries (Female)

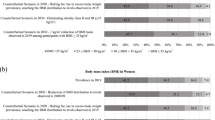

In GBD 2019, 13 cancer types were found to be affected by high BMI among females, including esophageal cancer, breast cancer, gallbladder and biliary tract cancer, liver cancer, uterine cancer, pancreatic cancer, multiple myeloma, colon and rectum cancer, thyroid cancer, kidney cancer, ovarian cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and leukemia. Breast cancer showed a consistent decrease in DALYs and deaths among females in the included countries with the highest decrease among United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia with − 2614%, -1019% respectively. Across all countries, the most significant percentage changes in cancer deaths attributed to BMI were observed for pancreatic cancer, uterine cancer, and kidney cancer with uptrend increases in DALYs, deaths, ASDR, and ASMR from 1990 to 2019. Notably, pancreatic cancer in the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia saw the highest percentage increase in DALYs (2292%, 1654% respectively) and deaths (2052%, 1455% respectively) attributed to BMI during this period. Additionally, pancreatic cancer in Saudi Arabia experienced the highest percentage increase in ASDR (420.3%) and ASMR (442.1%). For uterine cancer, across all countries, the most significant percentage changes in uterine cancer deaths attributed to high BMI was in the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia with percentage increase in DALYs (794.5%, 528.7% respectively) and deaths (663.9%, 433.6% respectively) attributed to BMI during this period (Supplementary Table 1 A, Fig. 3).

3.5 DALYs and Deaths of Specific Cancer Type Attributable to High BMI in 2019 and Percentage Change from 1990 to 2019 by Cancer Types and GCC Countries (Male)

In GBD 2019, 10 cancer types were found to be affected by high BMI among males, including esophageal cancer, gallbladder and biliary tract cancer, liver cancer, pancreatic cancer, multiple myeloma, colon and rectum cancer, thyroid cancer, kidney cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and leukemia. Across all countries, the most significant percentage changes in cancer deaths attributed to BMI in males were observed for colon and rectum cancer, esophageal cancer, kidney cancer and liver cancer with uptrend increases in DALYs, deaths, ASDR, and ASMR from 1990 to 2019. Notably, colon and rectum cancer deaths and DALY’s attributed to BMI in United Arab Emirates, and Qatar saw the highest percentage increase in DALYs (1423%, 1194% respectively) and deaths (1361%, 1226% respectively) attributed to BMI during this period. Oman experienced the highest percentage increase in colon and rectum cancer deaths attributed to BMI ASDR (222.5%) and ASMR (291.2%). Additionally, esophageal cancer deaths and DALY’s attributed to BMI in United Arab Emirates, and Qatar saw the highest percentage increase in DALYs (1811%, 733% respectively), and deaths (1758%, 750.7% respectively) during the study period (Supplementary Table 2B, Fig. 3).

3.6 Association Between SDI and Burden of Cancer Attributable to High BMI

The SDI-based analysis showed that the death rate of cancer attributable to high BMI increased along with the increase in SDI level. In addition, The ASMR of cancer attributable to high BMI has increased in all GCC countries except for Bahrain which showed a decline in ASMR of cancer attributable to high BMI. The associations reflected a significantly positive correlation between the ASMR and SDI level in Saudi Arabia (R = 0.99, p < 0.0001), followed by Qatar and Oman with a similar correlation (R = 0.92, p < 0.0001). Only Bahrain showed a significantly negative weak correlation (R= -0.38, p = 0.03; Fig. 4).

The association between SDI and the ASMR of cancer attributable to high BMI in 2019. Spearman’s correlation analysis reflected a significantly positive correlation between the ASMR and SDI level. Only Bahrain show significantly negative correlation was found between the ASMR and SDI level. ASMR, age-standardized mortality rate; BMI, body mass index; SDI, Socio-demographic Index

4 Discussion

Our findings reveal that in 2019, the GCC countries experienced over 102,206 cancer-related deaths. Among these, 2,210 (2.16%) deaths were attributed to high BMI, with an ASMR of 10 per 100,000. Notably, the ASMR associated with high BMI exceeded that of high socio-demographic countries (estimated at 7.52 per 100,000) and higher than the global ASMR (estimated at 5.69 per 100,000) for the same period [29–30]. Additionally, the collective burden of cancer-related DALYs amounted to 322,168 thousand. Of this total, 1.28% (4152 thousand) was attributed to high BMI, corresponding to an ASDR of 213.254 per 100,000 in 2019. Again, this ASDR surpassed that of high socio-demographic countries (ASDR: 174.68 per 100,000) and the global average (ASDR: 133.93 per 100,000). [29–30] This could be attributed to the ongoing exponential rise of obesity in GCC countries. Indeed, due to the significant modernization and adoption of the “Western lifestyle” in the last three decades, GCC countries are among the regions with the highest prevalence of obesity globally and even higher than high-income countries [4, 31–32]. These findings offer important information that can guide policymakers in creating effective prevention programs. Strategies aimed at reducing weight and encouraging physical activity could greatly lessen the impact of diseases in the GCC countries.

It is evident in previous studies that regions with higher SDI levels tended to carry a heavier burden of cancer attributed to high BMI [29–30]. Notably, the GCC countries, were all categorized as high SDI countries, except for Bahrain classified as a middle high SDI country. This trend was reflected in our findings, with Bahrain being the only country showing fluctuations over the years, including a slight decline in terms of death numbers, DALYs, ASDR, and ASMR between 1990 and 2019. In contrast, the United Arab Emirates experienced a substantial surge in DALYs attributed to cancer related to high BMI, increasing approximately 16-fold, particularly driven by a notable rise in DALYs among males, which highlight a concerning trend in mortality rates in the UAE. These findings also confirm the commonality of the population trend of high BMI condition on high income countries including GCC countries. This alarming increase requires tremendous all levels efforts to curb the associated outcomes of prevalent obesity. In fact, high BMI has not shown a declining trend but has instead continued to rise, contributing to its ongoing global pandemic. As of 2016, approximately 40% of adults and 18% of children worldwide were classified as obese or overweight, highlighting the persistent and widespread nature of this public health issue. This suggests that the continuation of current patterns of population weight gain will lead to continuing increases in the future burden of cancer in high income countries including the gulf region.

The GCC countries have experienced an increase in cancer cases over recent years, posing a significant public health challenge [9–10, 21]. Our findings highlight a distinctive pattern where specific cancers linked to high BMI, such as colon, rectal, and liver cancers, showed higher DALYs and mortality rates in the GCC compared to global trends. For instance, the DALYS and mortality rate for liver cancer in the GCC are notably higher, with ASMR and ASDR around six times and four times respectively higher than the global rate. Moreover, colon and esophageal cancer in the GCC are higher, with ASMR and ASDR around three times higher to the global rate [29]. All the above could explain the findings of increased deaths and the burden of cancer attributable to high BMI in GCC countries. On the other hand, our study reveals a consistent decrease in breast cancer DALYs and deaths among females, with the most substantial reductions observed in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. This noteworthy decline may be attributed to heightened awareness campaigns and programs leading to improved early detection practices. Additionally, advancements in therapy and healthcare interventions in recent years likely play a crucial role in the observed decrease in the overall burden of breast cancer in the specified countries [33].

In 2019, across GCC countries, pancreatic cancer, uterine cancer, and kidney cancer accounted for 87.91% of the total attributable deaths associated with high BMI in female. In contrast in males, colon and rectum cancer alone accounted for 26% of all attributable deaths associated with high BMI. Combined colon and rectum cancer, esophageal cancer, kidney cancer and liver cancer accounted for 70% of all attributable deaths associated with high BMI. If we assume a causal relationship between high BMI and cancer, maintaining current trends of population weight gain will likely result in ongoing increases in the future burden of cancer. Significantly, approximately one-quarter of all cases attributed to high BMI (118,000 cancers) might have been preventable if the global population’s average BMI had stayed consistent with 1982 levels [23]. These findings provide policymakers with actionable data to inform evidence-based decision-making, prioritize resource allocation, and develop targeted interventions aimed at reducing the burden of cancer associated with high BMI. By addressing risk factors associated with specific cancer types, such as colon and rectum cancer in males and pancreatic, uterine, and kidney cancer in females, policymakers can tailor their efforts to reduce the burden of these diseases effectively.

Despite the higher prevalence and incidence of obesity among females compared to males in GCC countries [31, 34], persistent gender disparities are evident in the cancer burden associated with high BMI, with males having a greater disease burden and mortality related to high BMI. This observation warrants exploration, and one potential explanation is the differential impact of obesity on cancer types between genders. Specifically, certain cancer types associated with obesity, such as colon and rectum cancer, may be more prevalent and fatal in males than in females. This disparity in cancer-specific outcomes could contribute to the overall higher disease burden and mortality observed in males with obesity-related cancers. Another reason could be the difference in the biological nature of obesity in males and females. Males tend to have a higher prevalence of abdominal obesity, characterized by excess fat around the abdomen, which is particularly linked to an increased risk of more deadly diseases such as cardiovascular diseases [35,36,37] Abdominal obesity is associated with insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and inflammation, all of which contribute to the development and progression of cardiovascular diseases [38–39]. This might also contribute to the increased cancer burden associated with high BMI in males. Further research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving these gender disparities and to develop targeted interventions aimed at reducing the cancer burden associated with obesity in both males and females.

4.1 Limitations

This study has several potential limitations to consider. Firstly, population-level data may introduce ecological fallacy bias by incorrectly assuming that patterns or characteristics observed at the population level are true for individuals within that population. Secondly, while BMI is widely used, it doesn’t account for the percentage of body fat and different patterns of obesity [40–41]. This means that categorizing BMI may not accurately reflect the impact of high BMI on cancer in specific populations. Thirdly, the process of cancer development involves various factors, and this study doesn’t account for other potential influences that may interact with high BMI such as family history of cancer, introducing the possibility of confounding bias that could affect the results. Finally, in GBD 2019, data on high BMI prevalence and cancer mortality were collected for the same year, making it challenging to assess any time interval between exposure and the development of cancer and mortality.

5 Conclusion

Our study highlights the significant impact of high BMI on cancer burden in GCC countries, revealing that in 2019, over 102,206 cancer-related fatalities occurred, with 2,210 (2.16%) attributed to high BMI, surpassing ASMRs of both high socio-demographic countries and the global average. This is concerning given the escalating rates of obesity in the region, driven by modernization and Western lifestyle adoption. Particularly alarming is the 16-fold increase in DALYs attributed to high BMI in the United Arab Emirates, emphasizing a pressing need for intervention. Moreover, the study identifies specific cancers, such as pancreatic, uterine, and kidney cancer in females, and colon and rectum cancer in males, as major contributors to attributable deaths, urging targeted prevention strategies. This study provides valuable insights into the contribution of high BMI to the burden of cancer in the GCC countries, one of the regions globally with the highest prevalence of obesity. These findings offer important information that can guide policymakers in creating effective prevention programs. Strategies aimed at reducing weight and encouraging physical activity could greatly lessen the impact of diseases in the GCC countries.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from [Global Burden of Disease Study 2019]. No restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under Public Use Files (PUF) data. Data are available at https://vizhub.healthdata.org.

Abbreviations

- ASDR:

-

Age-standardized DALYs rate

- ASMR:

-

Age-standardized mortality rate

- ASR:

-

Age-standardized rate

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life-years

- APC:

-

Annual percentage change

- PAFs:

-

Population attribution fraction

- GBD:

-

Global Burden of Diseases

- SDI:

-

Socio-Demographic Index

- UI:

-

Uncertainty interval

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

References

Dai H, Alsalhe TA, Chalghaf N, Riccò M, Bragazzi NL, Wu J. The global burden of disease attributable to high body mass index in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2020;17(7):e1003198-. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003198.

Ortega FB, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Obesity and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res [Internet]. 2016;118(11):1752–70. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306883.

El Bcheraoui C, Afshin A, Charara R, Khalil I, Moradi-Lakeh M, Kassebaum NJ et al. Burden of obesity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2015 study. Int J Public Health [Internet]. 2018;63(1):165–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-1002-5.

Hruby A, Hu FB. The Epidemiology of obesity: A big picture. Pharmacoeconomics [Internet]. 2015;33(7):673–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x.

Sultan Fahad Alnohair. Obesity in Gulf Countries. Int J Health Sci. 2014;8(1).

Tyrovolas S, El Bcheraoui C, Alghnam SA, Alhabib KF, Almadi MAH, Al-Raddadi RM et al. The burden of disease in Saudi Arabia 1990–2017: results from the Global Burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Planet Health [Internet]. 2020;4(5):e195–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30075-9.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet [Internet]. 2014;384(9945):766–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8.

Aldubikhi A. Obesity management in the Saudi population. Saudi Med J [Internet]. 2023;44(8):725. http://smj.org.sa/content/44/8/725.abstract.

Arafa MA, Rabah DM, Farhat KH. Rising cancer rates in the Arab World: now is the time for action. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(6):638–40.

Al-Othman S, Haoudi A, Alhomoud S, Alkhenizan A, Khoja T, Al-Zahrani A. Tackling cancer control in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries. Lancet Oncol [Internet]. 2015;16(5):e246–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70034-3.

Pati S, Irfan W, Jameel A, Ahmed S, Shahid RK. Obesity and Cancer: A Current Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Outcomes, and Management. Cancers (Basel) [Internet]. 2023;15(2). https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/15/2/485.

Munsell MF, Sprague BL, Berry DA, Chisholm G, Trentham-Dietz A. Body Mass Index and Breast Cancer Risk According to Postmenopausal Estrogen-Progestin Use and Hormone Receptor Status. Epidemiol Rev [Internet]. 2014;36(1):114–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxt010.

Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F, Zhang P, Shi C, Zou Y et al. Obesity and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. PLoS One [Internet]. 2013;8(1):e53916-. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053916.

Jenabi E, Poorolajal J. The effect of body mass index on endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Public Health [Internet]. 2015;129(7):872–80. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033350615001912.

Renehan AG, Zwahlen M, Egger M. Adiposity and cancer risk: new mechanistic insights from epidemiology. Nat Rev Cancer [Internet]. 2015;15(8):484–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3967.

Rogers CJ, Prabhu KS, Vijay-Kumar M. The Microbiome and Obesity—An Established Risk for Certain Types of Cancer. The Cancer Journal [Internet]. 2014;20(3). https://journals.lww.com/journalppo/fulltext/2014/05000/the_microbiome_and_obesity_an_established_risk_for.3.aspx.

Bhaskaran K, Douglas I, Forbes H, dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Smeeth L. Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5·24 million UK adults. The Lancet [Internet]. 2014 Aug 30;384(9945):755–65. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60892-8.

Zacharakis G, Almasoud A, Arahmane O, Alzahrani J, Al-Ghamdi S, Epidemiology. Risk Factors for Gastric Cancer and Surveillance of Premalignant Gastric Lesions: A Prospective Cohort Study of Central Saudi Arabia. Current Oncology [Internet]. 2023;30(9):8338–51. https://www.mdpi.com/1718-7729/30/9/605.

Alshamsan B, Suleman K, Agha N, Abdelgawad MI, Alzahrani MJ, Elhassan T, et al. Association between Obesity and Clinicopathological Profile of patients with newly diagnosed non-metastatic breast Cancer in Saudi Arabia. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:373–84.

Ramadan M, Alsiary RA, Aboalola DA. Mortality-to-incidence ratio of early-onset colorectal cancer in high-income Asian and Middle Eastern countries: A systemic analysis of the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2019. Cancer Med [Internet]. 2023;12(21):20604–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.6631.

Jazieh AR, Da’ar OB, Alkaiyat M, Zaatreh YA, Saad AA, Bustami R et al. Cancer Incidence Trends From 1999 to 2015 And Contributions Of Various Cancer Types To The Overall Burden: Projections To 2030 And Extrapolation Of Economic Burden In Saudi Arabia. Cancer Manag Res [Internet]. 2019;11(null):9665–74. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S222667.

Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020;396(10258):1204–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9.

Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, Renehan AG, Stevens GA, Ezzati M et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol [Internet]. 2015;16(1):36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71123-4.

O’Neill RJ, Abd Elwahab S, Kerin MJ, Lowery AJ. Association of BMI with Clinicopathological Features of Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Surg [Internet]. 2021;45(9):2805–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-021-06193-2.

Hidayat K, Li HJ, Shi BM. Anthropometric factors and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma risk: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol [Internet]. 2018;129:113–23. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040842817304882.

Tentolouris A, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Terpos E. Obesity and multiple myeloma: Emerging mechanisms and perspectives. Semin Cancer Biol [Internet]. 2023;92:45–60. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1044579X23000615.

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. (GBD 2019) Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) 1950–2019. Seattle, United States of America: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). 2020.

Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020;396(10258):1223–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2.

Zhi X, Kuang X, hong, Liu K, Li J. The global burden and temporal trend of cancer attributable to high body mass index: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Front Nutr [Internet]. 2022;9. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.918330.

Li X, Han F, Liu N, Feng X, Sun X, Chi Y et al. Changing trends of the diseases burden attributable to high BMI in Asia from 1990 to 2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023;13(10). https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/10/e075437.

Althumiri NA, Basyouni MH, AlMousa N, AlJuwaysim MF, Almubark RA, BinDhim NF et al. Obesity in Saudi Arabia in 2020: Prevalence, Distribution, and Its Current Association with Various Health Conditions. Healthcare [Internet]. 2021;9(3). https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/9/3/311.

Sulaiman N, Elbadawi S, Hussein A, Abusnana S, Madani A, Mairghani M et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in United Arab Emirates expatriates: the UAE National Diabetes and Lifestyle Study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2017;9.

Karima Chaabna H, Ladumor S, Cheema. Ecological study of breast cancer incidence among nationals and nonnationals in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. East Mediterr Health J. 2023;19(1):40–8.

Okati-Aliabad H, Ansari-Moghaddam A, Kargar S, Jabbari N. Prevalence of Obesity and Overweight among Adults in the Middle East Countries from 2000 to 2020: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Velotti N, editor. J Obes [Internet]. 2022;2022:8074837. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8074837.

Dhawan D, Sharma S. Abdominal Obesity, Adipokines and Non-communicable Diseases. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol [Internet]. 2020;203:105737. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960076020302624.

Wong MCS, Huang J, Wang J, Chan PSF, Lok V, Chen X et al. Global, regional and time-trend prevalence of central obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13.2 million subjects. Eur J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2020;35(7):673–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-020-00650-3.

Cooper AJ, Gupta SR, Moustafa AF, Chao AM. Sex/Gender Differences in Obesity Prevalence, Comorbidities, and Treatment. Curr Obes Rep [Internet]. 2021;10(4):458–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-021-00453-x.

Ragino YI, Stakhneva EM, Polonskaya YV, Kashtanova EV. The Role of Secretory Activity Molecules of Visceral Adipocytes in Abdominal Obesity in the Development of Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. Biomolecules [Internet]. 2020;10(3). https://www.mdpi.com/2218-273X/10/3/374.

Hamjane N, Benyahya F, Nourouti NG, Mechita MB, Barakat A. Cardiovascular diseases and metabolic abnormalities associated with obesity: What is the role of inflammatory responses? A systematic review. Microvasc Res [Internet]. 2020;131:104023. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0026286220300832.

Gallagher D, Visser M, Sepúlveda D, Pierson RN, Harris T, Heymsfield SB. How Useful Is Body Mass Index for Comparison of Body Fatness across Age, Sex, and Ethnic Groups? Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 1996;143(3):228–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008733.

Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, Jebb SA, Murgatroyd PR, Sakamoto Y. Healthy percentage body fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index123. Am J Clin Nutr [Internet]. 2000;72(3):694–701. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002916523067606.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the work by the Global Burden of Disease study 2019 collaborator.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R. and R.B. contributed equally to the work. M.R. and R.B. designed and conducted the present study and drafted the manuscript; RB performed the data analysis and achieved the acquisition of data, and M.R., S.K., N.A., A.A., N.S. made critical revisions and final approval of the manuscript. All other authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All authors confirm that they had full access to all the data in the study and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC). The Biomedical ethics committee in KAIMRC exempts this study from IRB due to public use data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramadan, M., Bajunaid, R.M., Kazim, S. et al. The Burden Cancer-Related Deaths Attributable to High Body Mass Index in a Gulf Cooperation Council: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J Epidemiol Glob Health 14, 379–397 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44197-024-00241-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44197-024-00241-5