Abstract

Background

Prior research suggests that dysbiotic gut microbiomes may contribute to elevated health risks among American Indians. Diet plays a key role in maintaining a healthy gut microbiome, yet suboptimal food environments within American Indian communities make obtaining nutritious food difficult.

Objective

This project characterizes the retail food environment within a rural tribal community, focused on the availability of foods that enhance the health and diversity of the gut microbiome, as well as products that reduce microbiome health (alcohol and tobacco).

Design

Audits were conducted of all retail stores that sell food within nine communities within the Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribal Jurisdictional Area in western Oklahoma.

Main measures

Freedman Grocery Store Survey.

Key results

Alcohol and tobacco were generally far more available in stores than foods that support a healthy gut microbiome, including fruits, vegetables, lean meats, and whole grain bread. Out of the four store types identified in the study area, only supermarkets and small grocers offered a wide variety of healthy foods needed to support microbiota diversity. Supermarkets sold the greatest variety of healthy foods but could only be found in the larger communities. Convenience stores and dollar stores made up 75% of outlets in the study area and offered few options for maintaining microbiome health. Convenience stores provided the only food source in one-third of the communities. With the exception of small grocers, alcohol and tobacco products were widely stocked across all store types.

Conclusions

The retail food environment in the Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribal Jurisdictional Area offered limited opportunities for maintaining a healthy and diverse microbiome, particularly within smaller rural communities. Additional research is needed to explore the relationship between food environment, dietary intake, and microbiome composition. Interventions are called for to increase the availability of “microbe-friendly” foods (e.g., fresh produce, plant protein, fermented and high fiber foods) in stores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

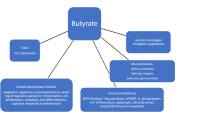

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts trillions of microorganisms that together comprise the gut microbiome (GM). This diverse community of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoans play a key role in maintaining human health by supporting metabolic function, immune defense, and nutrient synthesis [1]. Dietary practices in turn exert a strong influence on the diversity and health of microbiota communities [2]. Over the past two decades, a large body of literature has begun to untangle the complex relationship between dietary habits and GM composition [3, 4], but few studies to date have explored how the broader food environment may impact GM health [5,6,7].

Emerging research posits the GM as an important link between the social environment and health disparities for poor and minoritized groups [8, 9]. The food environment—or the context through which people interact with the food system, including the availability, affordability, convenience, and quality of foods in built, cultivated or wild spaces [10]—can influence dietary intake and health outcomes [11,12,13,14]. Within the US and other high-income countries, residents rely on the retail food environment, or market-based food outlets that sell food commercially, for most of their dietary needs [15]. Yet food environments reflect broader social patterns of advantage and disadvantage, with low-income, racialized, and rural areas [16,17,18,19] offering fewer opportunities for nutritious and affordable foods (or “food deserts”) [20, 21], often combined with an abundance of processed, high-fat, and high-sugar options (“food swamps”) [22]. These suboptimal food environments contribute to unhealthful diets [16, 23, 24] and chronic conditions [24,25,26,27].

The GM performs multiple vital functions for human health and wellbeing. Diseases associated with GM dysbiosis, a term indicating altered microbiota composition and functionality, include cardiovascular disease [28], irritable bowel syndrome [29], colorectal cancer [6], type 2 diabetes [30], and obesity [31]. Dietary intake represents one of the largest determinants of GM composition [4, 32], yet western industrialized diets, consisting of processed foods high in fat and simple carbohydrates and low in fiber, lack many elements essential for sustaining a functional GM [33]. Researchers commonly use microbiota diversity to measure GM health [1, 34]. A diet rich in different food types, particularly a variety of unprocessed fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and other high-fiber foods [35, 36], supports microbiome diversity and resilience [37, 38]. As a result, food environments that offer a limited variety of these “whole foods” may contribute to impaired GM function, particularly for socially disadvantaged groups.

Prior research finds that American Indians face numerous barriers to accessing healthy and affordable foods [39, 40] and experience heightened rates of non-communicable diseases that have been linked to GM dysbiosis [41,42,43]. Compared to the general US population, American Indians exhibit significantly higher rates of cardiovascular diseases [44, 45], cancers [46,47,48], diabetes [49,50,51], obesity [52, 53], and other diseases of the metabolic syndrome [54, 55]. Although research on the retail food environment of Indigenous people remains relatively sparse, evidence suggests that contemporary food environments of American Indians, particularly those residing in rural contexts, fails to provide an adequate source of nutritious or affordable food [39, 40]. Residents of rural reservations must frequently travel long distances to access grocery stores, leaving them to rely more heavily on non-traditional food outlets, such as convenience stores and gas stations [56, 57]. In one study of food stores on 22 reservations in Washington state, researchers found that more than ¾ of residents lived over 10 miles from a grocery store [58]. The scarcity of full service grocery stores corresponded with high prevalences of dairy and sugar products and low availability of fresh fruits and vegetables [58]. Likewise, research on the Navajo Nation found that less healthy food is both more easily accessible and less expensive compared to more nutritious options [59, 60]. Other studies have linked reliance on non-traditional food outlets to adverse health outcomes in tribal communities. A study of 513 American Indians within the Chickasaw and the Choctaw Nations of Oklahoma found that regularly obtaining food from non-traditional food retailers was associated with obesity and diabetes [42].

The current study is part of a broader program of research dating back to 2010 on metabolic health, dietary habits, and food environments within the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal Jurisdictional Area (C&A TJA), a predominantly rural community in western Oklahoma. Our previous research found that Cheyenne and Arapaho participants’ self-reported diets largely consisted of processed (often fried) protein and carbohydrates, high-calorie snacks, and sweetened or caffeinated drinks [61]. Participants ate few fruits and consumed vegetables primarily in the form of potatoes. In turn, participants’ gut metabolite profiles resembled dysbiotic states found in metabolic disorders, with features observed in inflammatory bowel disorders [61, 62]. Specifically, individuals showed reduced microbial richness and an abundance of the bacterial phylum Firmicutes, primarily Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae (for recent reviews on the relationship betweeen microbiota composition, function, and health see [63, 64]).

Interviews conducted with 23 American Indian shoppers within the C&A TJA helped to contextualize these findings [65]. Participants reported obtaining the majority of their food from retail stores and eating most meals at home. Those who lived in very small towns (90–1250 population) traveled 62.9 miles roundtrip on average to acquire food, with some traveling even greater distances to avoid stores known to be racist. Many relied heavily on convenience stores that were closer but offered less healthy food. Some participants had developed a preference for what they described as unhealthy food (e.g., fried food), believing that healthy food (e.g., unfried food, fruits and vegetables) did not taste good.

This study was undertaken to better understand the C&A TJA retail food environment given our previous findings on microbial dysbiosis within Indigenous residents. We use food audits of retail stores to characterize the availability of foods that enhance GM health and diversity, as well as products that adversely affect GM health. Specifically, we examine the relationship between store type, food variety, and alcohol and tobacco.

2 Methods

This project examined the availability of GM enhancing food in the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal Jurisdictional Area (C&A TJA). More than 12,000 people are enrolled in the C&A Tribes, with over 8600 living within Oklahoma [66, 67]. The C&A TJA (formerly their late 19th-century reservation) includes 8996 square miles with more than fifty towns in the western part of the state [66]. The USDA categorizes most of the C&A TJA as having low access to healthy foods, where significant proportions of the population must travel farther than 1 mile (urban) or 10 miles (rural) to the nearest supermarket [68]. The median household income for the general population in the C&A TJA is $59,398 [69], slightly lower than the national median ($62,843) [70]. However, the median income for American Indians in Oklahoma is almost 20% lower compared to all households in the state. Non-Natives predominate within the Cheyenne-Arapaho Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area (OTSA), with those identifying as white comprising 81.7% of the total population (189,584). Compared to White Oklahomans, American Indian/Alaska Native residents are more likely to report diabetes (16.6% vs 12.4%), obesity (42.7% vs 35.5%), smoking (27.2% vs 18.9%), and fair or poor health status (22.8% vs 18.3%) [71, 72].

We audited all retail stores that sell food within nine C&A TJA communities. Participating communities ranged from small rural communities with 1–2 retail food outlets to more urbanized population centers with up to 17 retail food stores, including supermarkets, small grocers, and convenience stores (see Table 1). Food stores were identified using Google search, augmented by firsthand knowledge of team members who were tribal members and/or resided within the C&A TJA (e.g., small stores with minimal internet presence, recent store openings/closings). A total of 57 food stores were audited between March 2014 and June 2015. This study was approved by the Cheyenne & Arapaho Health Board and given exempt status as non-human subject research by The University of Oklahoma Institutional Review Board.

We measured food availability using the Freedman Grocery Store Survey (FGSS) [74, 75]. The FGSS ascertains the availability of healthy foods (e.g., fruit, vegetables, dairy products, juice, lean meats, whole-grain bread) as well as tobacco and alcohol products. We availed ourselves of the FGSS’s ability to assess the availability of tobacco and alcohol as an important comparator to healthy food availability, especially given the high rates of commercial tobacco and alcohol use in some tribal communities [71, 76,77,78], coupled with the long history of targeted marketing of these products to minority and low SES consumers [79, 80].

Food stores were coded into five types based on an adapted version of the FGSS [74], modified using rural categorizations developed by Bardenhagen et al. [81]. Store types included: supermarkets (i.e., stores selling a wide variety of items, including all major food groups, five or more different types of vegetables and five or more different kinds of fruits, reduced- or low-fat dairy products, and lean meats [74]), small to mid-sized grocers (i.e., stores selling a modest range of groceries and that focus on grocery over convenience items), convenience stores (i.e., limited variety food marts, with or without gas, that focus primarily on convenience items), dollar/discount stores (i.e., limited assortment stores specializing in discounted items, primarily housewares, décor, and other home goods), and farm/ranch stores (i.e., stores providing farm and ranch supplies, such as feed, tack, fencing, and tanks). Based on the audits, we found negligible food offerings at the farm and ranch stores and therefore excluded the category from the analysis, giving us a final sample of 55 stores. Convenience stores comprised the largest single category of food stores in the sample (61.2%), followed by supermarkets (14.5%), dollar/discount stores (12.7%), and small to mid-sized grocers (10.9%).

Our analysis focuses on the availability and variety of foods that promote GM health: fresh or frozen fruits and vegetables, whole grain bread, dairy, and unprocessed meat [82,83,84,85,86]. We also report findings on alcohol and tobacco availability, products known to contribute to GM dysbiosis [7, 87] and utilized at high rates in some tribal communities [71, 76,77,78]. To measure the variety of healthy food in stores, we created an index based on the ratio of available healthy foods to total measured options across five categories: fresh/frozen fruits, fresh/frozen vegetables, dairy, lean meat, and whole grain bread (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92, see Table 4 below for more details on index construction). A similar index measured alcohol and tobacco availability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74).

Data were entered into MS Excel and transferred into Stata/SE 17 for analysis. Analyses included descriptive statistics, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and linear regression.

3 Results

3.1 Store descriptions

Convenience stores with fuel made up 31 out of the 34 convenience stores in the study area and were the only source of food in three C&A TJA communities. The stores included a few national (Love’s and Phillips 66) and regional/state (Domino and Jiffy) chains, but most outlets were locally owned, including one tribally owned travel mart. These stores predominantly stocked snacks, candy, soda, beer, and tobacco. Most also had hot boxes at the checkout counters, with ready-to-eat foods, such as fried chicken, burritos, egg rolls, and potato wedges.

Three convenience stores did not have fueling stations and were all locally owned. Two stores in this category were formerly operated by national chains; the current owners removed the fuel pumps and placed steel security bars over the windows and doors, then reopened as corner stores serving nearby low-income residents who often came on foot. The third convenience store without fuel was previously an old-fashioned filling station with a mechanics’ garage before being converted into a retro corner store providing local customers with sandwiches, soups, fried foods, and gossip.

The eight supermarkets within our sample were located in the larger communities and offered a wide variety of food products. Supermarket locations included three national chains (Walmart), three regional chains (United and Homeland), and two local stores. In addition to traditional grocery selections, most supermarkets had hot food display cases with ready-to-eat and fried foods, often located near the deli counter.

Dollar/discount stores in the C&A TJA consisted primarily of Dollar Generals and Family Dollars and were also located within the four larger communities. These stores carried household goods, toiletries, and food, consisting largely of snacks, candy, soda, and shelf-stable boxed and canned items.

Some small to mid-sized grocers (hereafter small grocers) were small “mom and pop” grocers in small towns. Others were owned and operated by a popular regional fast-food chain (Braum’s Ice Cream & Dairy Store) that featured burgers, french fries, and ice cream, with an attached “Fresh Market” selling healthier foods (e.g., fresh produce, juices, dairy, meat), as well as sweet treats.

3.2 Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents the frequency of product availability across all store types. Out of the major healthy food categories, only dairy could be found at most stores (85.5%). Less than half of all stores stocked fresh/frozen fruits (38.2%), fresh/frozen vegetables (29.1%), whole grain bread (36.4%), and unprocessed meats (25.5%). Alcohol and tobacco, by contrast, were well represented, with at least 80% of stores stocking each of these items.

Out of the four store types, only supermarkets and small grocers tended to offer healthy options across all categories. Supermarkets and small grocers were the only reliable sources of unprocessed meat and fresh or frozen fruits and vegetables. About a quarter of convenience stores stocked some type of fruit but only one carried any type of vegetable. Nearly 80% of convenience stores carried dairy but very few (8.8%) offered whole grain bread. Dollar/discount stores could be relied on for dairy and whole grain bread but no other food category. With the exception of small grocers, alcohol and tobacco were widely available across all store types.

The food variety index measures the extent to which stores offered a variety of healthy options across multiple categories. Our findings show that most stores offered a limited variety of healthy foods (Table 3). The food variety index ranged from 0 to 1, with an average rating of 0.30 (SD 0.34), indicating that stores carried an average of about 6 of the 21 healthy food products documented in the survey. Six stores (10.9%), all convenience stores, received scores of zero and carried no healthy foods listed in the survey. Mean scores of the component variables show that stores carried the greatest variety in the dairy (0.48) and fruit (0.27) categories. Meat (0.16) and vegetables (0.23) received the lowest scores for healthy food variety. By contrast, the alcohol and tobacco index averaged 0.81 across all stores (SD 0.35). Seven stores (12.7%) sold no alcohol or tobacco, while 41 stores (74.5%) sold both product types.

Figure 1 and Table 4 show the mean index scores by store type. Supermarkets (0.92) and small grocers (0.62) scored highest for overall food variety and had relatively high scores across all categories. Dollar/discounts (0.33) scored third highest for food variety because of the availability of whole grain bread and dairy products. Convenience stores (0.10) ranked last with an average of 2 out of 21 healthy products available at stores. Convenience stores ranked below 0.50 on food variety across all categories. Apart from small grocers, all store types scored high on the alcohol/tobacco index.

3.3 ANOVAs

We conducted one-way ANOVAs to determine if the differences in food variety and alcohol/tobacco index scores between store types were statistically significant. For food variety, results show a statistically significant difference between groups (F(3,51) = 79.69, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.82). A Tukey post-hoc test revealed significantly higher food variety at supermarkets compared to convenience stores (0.82 ± 0.06, p < 0.001), dollar/discount stores (0.59 ± 0.07, p < 0.001), and small grocers (0.30 ± 0.08, p = 0.002). Small grocers exhibited greater food variety compared to convenience stores (0.52 ± 0.06, p < 0.001) and dollar/discount stores (0.29 ± 0.08, p = 0.004). Dollar/discount stores showed greater food variety compared to convenience stores (0.23 ± 0.06, p = 0.002).

ANOVA also shows an association between alcohol/tobacco and store type (F(3,51) = 20.10, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.54). Small grocers carried fewer alcohol/tobacco products compared to convenience stores (0.83 ± 0.11, p < 0.001), supermarkets (0.85 ± 0.13, p < 0.001), and dollar stores (0.70 ± 0.14, p < 0.001). Alcohol and tobacco availability did not significantly differ between convenience stores, supermarkets, and dollar stores.

3.4 Regression models

To further examine the relationship between store type and food variety, we ran a series of univariate regression analyses (Table 5). The models show a positive and significant relationship between food variety and store type for supermarkets (β = 0.73, t = 8.70, p < 0.001) and small grocers (β = 0.36, t = 2.63, p = 0.01). Convenience stores were negatively and significantly associated with food variety (β = − 0.48, t = − 7.52, p < 0.001). The regression analyses also show a significant relationship between store type and alcohol/tobacco product availability. Convenience stores were positively and significantly related to alcohol/tobacco availability (β = 0.32, t = 3.48, p = 0.001). Only small grocers showed a negative relationship with alcohol/tobacco (β = − 0.78, t = − 6.15, p < 0.001).

4 Discussion

This study represents a first step towards connecting food environments, gut microbiome, and health disparities. The GM has been shown to play a role in the etiology of numerous diseases that American Indians experience at disproportionate rates [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55], including cardiovascular disease [28], irritable bowel syndrome [29], colorectal cancer [6], diabetes [30], and obesity [31]. Diet exerts a strong influence on GM composition [4, 32], yet suboptimal retail food environments can present barriers to obtaining the variety and quality of foods needed to support vital GM functions [5,6,7]. The results of our study indicate limited availability of GM-enhancing foods within the retail food environment of the C&A TJA. These findings help to contextualize our previous research, which found that the diets of C&A participants consisted predominantly of processed proteins and carbohydrates, with low fruit and vegetable consumption [61]. In turn, the GM profiles of participants resembled dysbiotic states found in metabolic disorders [61, 62]. These finding also align with our earlier research documenting C&A residents’ challenges accessing healthy food [65].

Given the mounting evidence implicating GM in disease development, inequitable access to GM enhancing foods requires continued attention. Food environment measures specific to GM health first need to be developed and tested. Our study focused on select items from an existing tool (the FGSS) that measured availability of produce and food variety reasonably well but excluded some categories of microbe-friendly foods, including whole grains beyond 100% whole grain bread (e.g., rice, oatmeal, quinoa), plant protein (beans, legumes, nuts), and probiotics (yogurt, fermented foods). The availability of plant proteins is especially important given the adverse microbial outcomes associated with diets high in animal protein [4, 88, 89]. Similarly, our measure of GM-adverse products included only alcohol and tobacco availability and could be expanded in future studies. For example, increasing evidence suggests that common food additives can contribute to GM dysbiosis [90,91,92]. More precise measurements represent the next step towards investigating the statistical relationship between food environments and variation in human GM composition.

Future research in this area should also heed lessons from the vast food environment literature. Notably, serious critiques of “food environment” and related concepts (e.g., “food deserts” and “food swamps”) have emerged, with scholars casting doubt on the connection between food environments and health disparities. Some studies find only weak relationships between food environments and health outcomes, and increasing access alone often produces limited changes in dietary habits [93]. Because the adult GM tends to be relatively stable and resilient to short-term dietary changes [94], these findings may hold true for outcomes associated with the GM as well. Yet rather than suggesting that food environments are therefore unimportant, we advocate for models that recognize the complexity of social behavior and how political, economic, and cultural contexts shape dietary practices.

This research contributes to the small number of studies on the retail food environments of Indigenous people [39, 40]. In line with past research, we found significant barriers to accessing nutritious foods, particularly within the more rural communities [58,59,60, 65]. Our findings also confirm the importance of nontraditional food outlets, particularly convenience and dollar stores, as a food source in rural tribal communities [42, 65]. Notably, dollar stores have become a national growth industry in recent years. Three chains (Dollar General, Family Dollar, and Dollar Tree) made up nearly half of all new retail store openings in 2021 [95]. Dollar General alone manages over 18,000 stores in 47 states, with a 2021 net sales of $34.2 billion [96]. This rapid expansion has generated backlash from communities, accusing dollar stores of promoting “food desertification” and undercutting local businesses. Indeed, research shows that dollar stores rarely stock fresh produce [97] and once a dollar store enters a food desert, the area is less likely to attract a supermarket [98]. Dollar General’s refusal to submit to tribal jurisdiction has also created opposition in some tribal communities [99]. In response, some communities have enacted local ordinances restricting dollar stores, including limits on store density and fresh food requirements [100]. To our knowledge, the effectiveness of these policies for increasing rural food access has not been evaluated but represents an important avenue of future research.

Since the time of the food audits (2014–2015), the retail food market in the C&A TJA has continued to shift. Within the last five years, the nine communities sampled have gained five dollar/discount stores and lost three small grocers. Most of the remaining small grocers are Braum’s Fresh Market stores, which predominantly feature fast food and ice cream and sells healthier food in a separate section of the store. If this trend continues, small grocers could become a less viable option for obtaining healthy food. How people interact with the food environment has also changed with the increased availability and use of online grocery shopping and food delivery [15, 101], yet recent evidence suggests that many of these services are not available to residents of rural food deserts [102]. Continued research is needed to understand how these changes affect food access, dietary practices, and health outcomes within tribal communities.

5 Conclusion and future directions

This study examined the retail food environment within a rural Oklahoma tribal community to assess the availability of foods needed to support a healthy gut microbiome. Results indicate that the C&A TJA retail food environment offered limited opportunities for maintaining a healthy and diverse GM. Convenience and dollar/discount stores made up 75% of retail outlets in the nine communities within the study area, both store types that scored low on food variety and high on alcohol/tobacco availability. Supermarkets and small grocers provided the best option for acquiring a variety of healthy foods but were located predominately in the larger communities.

Despite persistent health disparities, intervention research centered on improving food security and access in Native American communities remains limited but critically important [103]. Significantly, interventions that adopt principles of Indigenous food sovereignty, including community-engaged methods and inclusion of traditional knowledge and foods, have proven effective in promoting dietary change [104]. For example, interventions to increase fresh food selection and purchases in tribal stores have shown promise and should be more widely implemented in other tribal communities [103, 105, 106]. Beyond a variety of fruits and vegetables, interventions targeting GM health could feature “microbe-friendly” foods, such as fermented and high fiber foods [8, 107] and plant protein [84]. The recent addition of fresh food within some dollar stores [108] represents another promising development that should be evaluated, especially in rural tribal communities.

As new programs and interventions are implemented, it will be crucial to consider local food preferences, as foods that may benefit the gut microbiome may be less familiar or not well aligned with customary foodways. Although food preferences are notoriously difficult to alter [109,110,111], it may be nonetheless possible to promote dietary changes at both the levels of individuals [112,113,114] and communities [112, 115]. Research focused on expanding food preferences to include microbe-friendly foods will be especially important to these efforts.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Shreiner AB, Kao JY, Young VB. The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31(1):69. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0000000000000139.

Gentile CL, Weir TL. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science. 2018;362(6416):776–80.

Wilson AS, Koller KR, Ramaboli MC, Nesengani LT, Ocvirk S, Chen C, et al. Diet and the human gut microbiome: an international review. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(3):723–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06112-w.

Frame LA, Costa E, Jackson SA. Current explorations of nutrition and the gut microbiome: a comprehensive evaluation of the review literature. Nutr Rev. 2020;78(10):798–812. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuz106.

Ishaq SL, Parada FJ, Wolf PG, Bonilla CY, Carney MA, Benezra A, et al. Introducing the Microbes and Social Equity Working Group: considering the microbial components of social, environmental, and health justice. Systems. 2021;6(4):e00471-e521. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00471-21.

Wolf PG, Byrd DA, Cares K, Dai H, Odoms-Young A, Gaskins HR, et al. Bile acids, gut microbes, and the neighborhood food environment—a potential driver of colorectal cancer health disparities. mSystems. 2022;7(1):e01174-e1221.

Ahn J, Hayes RB. Environmental influences on the human microbiome and implications for noncommunicable disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:277–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-012420-105020.

Amato KR, Arrieta M-C, Azad MB, Bailey MT, Broussard JL, Bruggeling CE, et al. The human gut microbiome and health inequities. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118:25. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2017947118.

Findley K, Williams DR, Grice EA, Bonham VL. Health disparities and the microbiome. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(11):847–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2016.08.001.

Downs SM, Ahmed S, Fanzo J, Herforth A. Food environment typology: advancing an expanded definition, framework, and methodological approach for improved characterization of wild, cultivated, and built food environments toward sustainable diets. Foods. 2020;9(4):532.

Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian S, Kawachi I. The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place. 2012;18(5):1172–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.006.

Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–72. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926.

Lake AA. Neighbourhood food environments: food choice, foodscapes and planning for health. Proc Nutr Soc. 2018;77(3):239–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665118000022.

de Albuquerque FM, Pessoa MC, De Santis FM, Gardone DS, de Novaes JF. Retail food outlets and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Nutr Rev. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab111.

Winkler MR, Zenk SN, Baquero B, Steeves EA, Fleischhacker SE, Gittelsohn J, et al. A model depicting the retail food environment and customer interactions: components, outcomes, and future directions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207591.

Morton LW, Blanchard TC. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy Starved for Access: Life in Rural America’s Food Deserts. Rural Realities Rural Development. 2007;1(4):1–10.

Walker RE, Keane CR, Burke JG. Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: a review of food deserts literature. Health Place. 2010;16(5):876–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.013.

Amin MD, Badruddoza S, McCluskey JJ. Predicting access to healthful food retailers with machine learning. Food Policy. 2021;99: 101985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101985.

Liese AD, Weis KE, Pluto D, Smith E, Lawson A. Food store types, availability, and cost of foods in a rural environment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(11):1916–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.012.

USDA ERS. Access to Affordable and Nutritious Food: Measuring and Understanding Food Deserts and Their Consequences: Report to Congress. Washington, DC: USDA: Economic Research Service. 2009.

Beaulac J, Kristjansson E, Cummins S. A Systematic Review of Food Deserts, 1966–2007. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(3):A105.

Fielding JE, Simon PA. Food deserts or food swamps?: Comment on “fast food restaurants and food stores.” Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1171–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.279.

Zenk SN, Powell LM, Rimkus L, Isgor Z, Barker DC, Ohri-Vachaspati P, et al. Relative and absolute availability of healthier food and beverage alternatives across communities in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2170–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302113.

Cooksey-Stowers K, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Food swamps predict obesity rates better than food deserts in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(11):1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111366.

Boone-Heinonen J, Gordon-Larsen P, Kiefe CI, Shikany JM, Lewis CE, Popkin BM. Fast food restaurants and food stores: longitudinal associations with diet in young to middle-aged adults: the CARDIA Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1162–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.283.

Kraft AN, Thatcher EJ, Zenk SN. Neighborhood food environment and health outcomes in US Low-Socioeconomic status, racial/ethnic minority, and rural populations: a Systematic review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(3):1078–114. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2020.0083.

Atanasova P, Kusuma D, Pineda E, Frost G, Sassi F, Miraldo M. The impact of the consumer and neighbourhood food environment on dietary intake and obesity-related outcomes: A systematic review of causal impact studies. Soc Sci Med. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114879s.

Ahmadmehrabi S, Tang WW. Gut microbiome and its role in cardiovascular diseases. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2017;32(6):761. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0000000000000445.

Tap J, Störsrud S, Le Nevé B, Cotillard A, Pons N, Doré J, et al. Diet and gut microbiome interactions of relevance for symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Microbiome. 2021;9(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-021-01018-9.

Zhu T, Goodarzi MO. Metabolites linking the gut microbiome with risk for type 2 diabetes. Current Nutrition Reports. 2020;9(2):83–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-020-00307-3.

Tilg H, Kaser A. Gut microbiome, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction. J Clin Investig. 2011;121(6):2126–32. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI58109.

David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12820.

Mancabelli L, Milani C, Lugli GA, Turroni F, Ferrario C, van Sinderen D, et al. Meta-analysis of the human gut microbiome from urbanized and pre-agricultural populations. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(4):1379–90.

Hills RD, Pontefract BA, Mishcon HR, Black CA, Sutton SC, Theberge CR. Gut microbiome: profound implications for diet and disease. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071613.

Klinder A, Shen Q, Heppel S, Lovegrove JA, Rowland I, Tuohy KM. Impact of increasing fruit and vegetables and flavonoid intake on the human gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2016;7(4):1788–96. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5FO01096A.

Holscher HD. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2017;8(2):172–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756.

Heiman ML, Greenway FL. A healthy gastrointestinal microbiome is dependent on dietary diversity. Mol Metab. 2016;5(5):317–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2016.02.005.

Xu Z, Knight R. Dietary effects on human gut microbiome diversity. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(S1):S1–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114514004127.

Kenny T-A, Little M, Lemieux T, Griffin PJ, Wesche SD, Ota Y, et al. The retail food sector and Indigenous peoples in high-income countries: A systematic scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):8818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238818.

Luongo G, Skinner K, Phillipps B, Yu Z, Martin D, Mah CL. The retail food environment, store foods, and diet and health among indigenous populations: A scoping review. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9(3):288–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-020-00399-6.

Jernigan VBB, Wetherill MS, Hearod J, Jacob T, Salvatore AL, Cannady T, et al. Food Insecurity and Chronic Diseases Among American Indians in Rural Oklahoma: The THRIVE Study. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):441–6. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2016.303605.

Love CV, Taniguchi TE, Williams MB, Noonan CJ, Wetherill MS, Salvatore AL, et al. Diabetes and Obesity Associated with Poor Food Environments in American Indian Communities: the Tribal Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments (THRIVE) Study. Curr Develop Nutr. 2018;3(2):63–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzy099.

Blue B, Jernigan V, Garroutte E, Krantz EM, Buchwald D. Food Insecurity and Obesity Among American Indians and Alaska Natives and Whites in California. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2013;8(4):458–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2013.816987.

Veazie M, Ayala C, Schieb L, Dai S, Henderson JA, Cho P. Trends and Disparities in Heart Disease Mortality Among American Indians/Alaska Natives, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S3):S359–67. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301715.

Mohammed SA, Udell W. American Indians/Alaska Natives and cardiovascular disease: outcomes, interventions, and areas of opportunity. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2017;11(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-017-0526-9.

Jackson CS, Oman M, Patel AM, Vega KJ. Health disparities in colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7(Suppl 1):S32–43. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.039.

Perdue DG, Haverkamp D, Perkins C, Daley CM, Provost E. Geographic variation in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, age of onset, and stage at diagnosis among American Indian and Alaska Native People, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S3):S404–14. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301654.

White MC, Espey DK, Swan J, Wiggins CL, Eheman C, Kaur JS. Disparities in cancer mortality and incidence among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S3):S377–87. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301673.

Subica AM, Agarwal N, Sullivan JG, Link BG. Obesity and Associated Health Disparities among understudied multiracial, Pacific Islander, and American Indian Adults. Obesity. 2017;25(12):2128–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21954.

Godwin CM. Diabetes in American Indian and Alaska Native Populations. Atlanta: Georgia State University; 2015.

Cho P, Geiss LS, Burrows NR, Roberts DL, Bullock AK, Toedt ME. Diabetes-related mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S3):S496–503. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301968.

Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States—gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29(1):6–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxm007.

Halpern P. Obesity and American Indians/Alaska Natives. In: USHHS, editor. Washington, DC: ASPE.HHS.gov; 2007.

Hutchinson RN, Shin S. Systematic Review of Health Disparities for Cardiovascular Diseases and Associated Factors among American Indian and Alaska Native populations. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e80973. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080973.

Schumacher C, Ferucci ED, Lanier AP, Slattery ML, Schraer CD, Raymer TW, et al. Metabolic syndrome: prevalence among American Indian and Alaska native people living in the southwestern United States and in Alaska. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2008;6(4):267–73. https://doi.org/10.1089/met.2008.0021.

Gustafson AA, Sharkey J, Samuel-Hodge CD, Jones-Smith J, Folds MC, Cai J, et al. Perceived and Objective Measures of the Food Store Environment and the Association with Weight and Diet Among Low-Income Women in North Carolina. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(6):1032–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011000115.

Sharkey JR. Measuring Potential Access to Food Stores and Food-Service Places in Rural Areas in the US American. J Prevent Med. 2009;36(4):S151–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.004.

O’Connell M, Buchwald DS, Duncan GE. Food Access and Cost in American Indian Communities in Washington State. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(9):1375–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.06.002.

Cunningham-Sabo L, Bauer M, Pareo S, Phillips-Benally S, Roanhorse J, Garcia L. Qualitative investigation of factors contributing to effective nutrition education for Navajo families. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(1):68–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0333-5.

Kumar G, Jim-Martin S, Piltch E, Onufrak S, McNeil C, Adams L, et al. Healthful nutrition of foods in Navajo Nation stores: Availability and pricing. Am J Health Promot. 2016;30(7):501–10.

Sankaranarayanan K, Ozga AT, Warinner C, Tito RY, Obregon-Tito AJ, Xu J, et al. Gut Microbiome Diversity among Cheyenne and Arapaho Individuals from Western Oklahoma. Current Biology: CB. 2015;25(24):3161–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.10.060.

Ozga AT, Sankaranarayanan K, Tito RY, Obregon-Tito AJ, Foster MW, Tallbull G, et al. Oral microbiome diversity among cheyenne and arapaho individuals from Oklahoma. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2016;161(2):321–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23033.

McBurney MI, Davis C, Fraser CM, Schneeman BO, Huttenhower C, Verbeke K, et al. Establishing what constitutes a healthy human gut microbiome: state of the science, regulatory considerations, and future directions. J Nutr. 2019;149(11):1882–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxz154.

Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, Franceschi F, Miggiano GAD, Gasbarrini A, et al. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms. 2019;7(1):14.

Jervis LL, Cox DW, TallBull G, Lowery BC, Spicer P. Food Inequality and the Industrialized Diet in a Rural Tribal Food Desert. under review.

Chatfield L. The Chickasaw Nation/Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma STEP Grant. Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Department of Education: Tribal Education Department, Department ODoETE; 2013.

Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission, Warner BA. Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory. Oklahoma City, OK: OIAC; 2011.

USDA ERS. Food access research atlas. 2019. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/go-to-the-atlas/. Accessed 23 May 2022.

US Census Bureau. My Tribal Area, 2015–2019 American Community Survey 5-year Estimates. https://www.census.gov/tribal/?st=40&aianihh=5560. Accessed 24 Feb 2022.

US Census Bureau. QuickFacts: Oklahoma. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/OK/AFN120212.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2017–2019.

US Census Bureau. City and Town Population Totals: 2010–2019. Washington, DC. 2021. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-total-cities-and-towns.html. Accessed Feb 12 2022.

Freedman DA, Bell BA. Access to healthful foods among an urban food insecure population: perceptions versus reality. J Urban Health. 2009;86(6):825–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-009-9408-x.

Sloane DC, Diamant AL, Lewis LB, Yancey AK, Flynn G, Nascimento LM, et al. Improving the nutritional resource environment for healthy living through community-based participatory research. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(7):568–75. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21022.x.

O’Connell JM, Novins DK, Beals J, Spicer P, AI‐Superpfp T. Disparities in patterns of Alcohol use among reservation‐based and geographically dispersed American Indian populations. Alcoholism. 2005;29(1):107–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ALC.0000153789.59228.FC

Nez Henderson P, Jacobsen C, Beals J, Team A-S. Correlates of cigarette smoking among selected Southwest and Northern plains tribal groups: the AI-SUPERPFP Study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(5):867–72. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.050096.

Spicer P, Beals J, Croy CD, Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Moore L, et al. The prevalence of DSM-III-R alcohol dependence in two American Indian populations. Alcoholism. 2003;27(11):1785–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ALC.0000095864.45755.53.

Lee JG, Henriksen L, Rose SW, Moreland-Russell S, Ribisl KM. A systematic review of neighborhood disparities in point-of-sale tobacco marketing. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e8–18. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302777.

Lempert LK, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry promotional strategies targeting American Indians/Alaska Natives and exploiting tribal sovereignty. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(7):940–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nty048.

Bardenhagen CJ, Pinard CA, Pirog R, Yaroch AL. Characterizing rural food access in remote areas. J Community Health. 2017;42(5):1008–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0348-1.

Iqbal R, Dehghan M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, Wielgosz A, Avezum A, et al. Associations of unprocessed and processed meat intake with mortality and cardiovascular disease in 21 countries [Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Study]: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;114(3):1049–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa448.

Aslam H, Marx W, Rocks T, Loughman A, Chandrasekaran V, Ruusunen A, et al. The effects of dairy and dairy derivatives on the gut microbiota: A systematic literature review. Gut Microbes. 2020;12(1):1799533. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2020.1799533.

Wu S, Bhat ZF, Gounder RS, Ahmed IA, Al-Juhaimi FY, Ding Y, et al. Effect of dietary protein and processing on gut microbiota—a systematic review. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):453. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030453.

van der Merwe M. Gut microbiome changes induced by a diet rich in fruits and vegetables. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2021;72(5):665–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2020.1852537.

Seal CJ, Courtin CM, Venema K, de Vries J. Health benefits of whole grain: Effects on dietary carbohydrate quality, the gut microbiome, and consequences of processing. Compreh Rev Food Sci Food Safety. 2021;20(3):2742–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12728.

Capurso G, Lahner E. The interaction between smoking, alcohol and the gut microbiome. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31(5):579–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2017.10.006.

Cai J, Chen Z, Wu W, Lin Q, Liang Y. High animal protein diet and gut microbiota in human health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2021.1898336.

Bolte LA, Vila AV, Imhann F, Collij V, Gacesa R, Peters V, et al. Long-term dietary patterns are associated with pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory features of the gut microbiome. Gut. 2021;70(7):1287–98.

Laudisi F, Stolfi C, Monteleone G. Impact of food additives on gut homeostasis. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2334. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102334.

Cao Y, Liu H, Qin N, Ren X, Zhu B, Xia X. Impact of food additives on the composition and function of gut microbiota: A review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;99:295–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2020.03.006.

Roca-Saavedra P, Mendez-Vilabrille V, Miranda JM, Nebot C, Cardelle-Cobas A, Franco CM, et al. Food additives, contaminants and other minor components: Effects on human gut microbiota—A review. J Physiol Biochem. 2018;74(1):69–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13105-017-0564-2.

Zhen C. Food Deserts: Myth or Reality? Annual Review of Resource Economics. 2021;13:109–29. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-101620-080307.

Voreades N, Kozil A, Weir TL. Diet and the development of the human intestinal microbiome. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:494. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00494.

Meyersohn N. Nearly 1 in 3 new stores opening in the US is a Dollar General. In: CNN. 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/05/06/business/dollar-store-openings-retail/index.html.

Dollar General Fast Facts. 2022. https://newscenter.dollargeneral.com/company-facts/fastfacts/.

Caspi CE, Pelletier JE, Harnack L, Erickson DJ, Laska MN. Differences in Healthy Food Supply and Stocking Practices between Small Grocery Stores, Gas-Marts, Pharmacies and Dollar Stores. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(3):540–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015002724.

Chenarides L, Cho C, Nayga RM Jr, Thomsen MR. Dollar stores and food deserts. Appl Geogr. 2021;134: 102497.

Klamath Tribes oppose Dollar General store due to court challenge. Indianz.com. 2016. https://www.indianz.com/News/2016/03/01/klamath-tribes-oppose-dollar-g.asp. Accessed 25 Apr 2022.

Donahue M, Smith K. Dollar Store Restrictions. Institute for Local Self Reliance (ILSR). 2022. https://ilsr.org/rule/dollar-store-dispersal-restrictions/. Accessed 28 Apr 2022.

Granheim SI, Løvhaug AL, Terragni L, Torheim LE, Thurston M. Mapping the digital food environment: a systematic scoping review. Obes Rev. 2022;23(1): e13356.

Brandt EJ, Silvestri DM, Mande JR, Holland ML, Ross JS. Availability of grocery delivery to food deserts in states participating in the online purchase pilot. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1916444.

Blue Bird Jernigan V, D’Amico EJ, Duran B, Buchwald D. Multilevel and community-level interventions with Native Americans: Challenges and opportunities. Prevention Science. 2020;21(1):65–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0916-3

Maudrie TL, Colón-Ramos U, Harper KM, Jock BW, Gittelsohn J. A Scoping Review of the Use of Indigenous Food Sovereignty Principles for Intervention and Future Directions. Curr Develop Nutr. 2021;5(7):093. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzab093.

Williams MB, Wang W, Taniguchi T, Salvatore AL, Groover WK, Wetherill M, et al. Impact of a healthy retail intervention on fruits and vegetables and total sales in tribally owned convenience stores: findings from the THRIVE Study. Health Promot Pract. 2021;22(6):796–805.

Gittelsohn J, Kim EM, He S, Pardilla M. A food store–based environmental intervention is associated with reduced BMI and improved psychosocial factors and food-related behaviors on the Navajo Nation. J Nutr. 2013;143(9):1494–500. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.112.165266.

Leeuwendaal NK, Stanton C, O’Toole PW, Beresford TP. Fermented foods, health and the gut microbiome. Nutrients. 2022;14(7):1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14071527.

Messer S, Worley B, McCarthy K. How dollar store grocery options stack up to traditional stores. ABC News. 2022. https://abcnews.go.com/GMA/Food/dollar-store-grocery-options-stack-traditional-stores/story?id=83292877#. Accessed 28 Apr 2022.

Roberto CA, Kawachi I. Use of psychology and behavioral economics to promote healthy eating. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(6):832–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.002.

Thorgeirsson T, Kawachi I. Behavioral economics: merging psychology and economics for lifestyle interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):185–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.008.

Yau YH, Potenza MN. Stress and eating behaviors. Minerva Endocrinol. 2013;38(3):255.

Buettner D. The blue zones: 9 lessons for living longer from the people who've lived the longest: National Geographic Books; 2012.

Buettner D, Skemp S. Blue zones: lessons from the world’s longest lived. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10(5):318–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827616637066.

Wilson B. First bite: how we learn to eat. New York: Basic Books; 2015.

Blue B, Jernigan V, Salvatore AL, Williams M, Wetherill M, Taniguchi T, Jacob T, et al. A healthy retail intervention in Native American convenience stores: the THRIVE community-based participatory research study. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):132–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LJ was the PI of this study, and took the lead on data analysis and manuscript preparation. LB and DC analyzed data and played central roles in manuscript writing. GTB assisted with study design, community outreach, and manuscript review. BL consulted on methods and edited the manuscript. PS assisted with study design and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jervis, L.L., Bray, L.A., Cox, D.W. et al. Food environments and gut microbiome health: availability of healthy foods, alcohol, and tobacco in a rural Oklahoma tribal community. Discov Food 2, 20 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44187-022-00020-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44187-022-00020-w