Abstract

Purpose

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has underscored how ill-prepared healthcare systems are for mass casualty events (MCEs,) especially as MCEs increase worldwide. We hypothesized that resident physicians (RPs) across multiple specialties are underprepared for MCE.

Methods

Two similar surveys were conducted to assess awareness of disaster plans (DPs) and individual’s roles and responsibilities therein. Initially, we surveyed exclusively trainees who are trauma team members (TTMs,) including physician assistants (PAs), residents from emergency medicine (EMRs) and general surgery (GSRs.) Subsequently, we surveyed multi-specialty RPs, except GSRs and EMRs, and their program directors/associate program directors (PDs/APDs.) RPs’ awareness, knowledge of, and confidence in hospital MCE response plans were assessed, and barriers encountered were queried. Data were consolidated except with respect to PDs/APDs, who were queried only in the second survey. The Fisher exact test for multiple-group comparisons was used. Alpha = 0.05.

Results

For the first survey, the response rate was 74% (123/166), whereas 34% (129/380) responded to the second survey. Combined, the response rate was 46% (252/546.) Considering the RPs only for the two surveys combined, 103 (53%) respondents reported no awareness of institutional MCE response plans, 73% (n = 143) did not know/were unsure whether they were expected to contact someone, and 68% (n = 134) reported no formal MCE/disaster management (DM) training over the prior year. Additionally, the median response reported for level of knowledge of the MCE response plan among all RPs was “not at all,” with a significant difference observed between those aware of the plan and those who were not (p < 0.001). The median response reported for confidence level of RPs in MCE/DM training, excluding GSRs and EMRs (TTMs,) was “not at all,” with significant differences between surgical and non-surgical specialty RPs (p = 0.031), and between junior and senior RPs (p = 0.027). PDs/APDs (n = 12) reported “time” as the main barrier to implementation.

Conclusions

RPs across all surveyed specialties reported low levels of knowledge and minimal training regarding MCE/DM. Incorporation of MCE/DM preparedness into residency training in all specialties involving direct patient care is essential. Curricular restructuring will be required for meaningful participation of RPs in MCEs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A mass casualty incident (MCI), as defined by the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS; Salt Lake City, UT) [1], is “an event (that) generates more patients at one time than locally available resources can manage using routine procedures or resulting in a number of victims large enough to disrupt the normal course of emergency and health care services, and (that) would require additional non-routine assistance.” MCIs, also called mass casualty events (MCEs) globally, include exposure to nuclear, biological, or chemical (NBC) agents that can be generated either by human activity or by natural disasters [2]. Although infrequent, MCEs represent major public health emergencies as they can overwhelm quickly even well-resourced hospitals with an onslaught of tens-to-thousands of critically injured individuals. Additionally, hospitals themselves have been subjected to major incidents such as power loss, flooding, or fire [3]. From 2000 to 2019, MCEs claimed 1.23 million lives costing approximately US$2.97 trillion, a sharp increase over the previous twenty years, posited to be related to an increase in weather-related disasters [4, 5].

Review of past incidents and recent surveys in the United States (US) have shown that hospital staff and resident physicians (RPs) remain uncomfortable with current disaster mitigation materials and protocols [2, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Insufficient training and inadequate equipment not only cost lives, but also put hospital staff at risk, as experienced during Hurricane Katrina [20]; the Fukushima, Japan nuclear disaster [30]; and with the COVID-19 pandemic [25, 26]. Furthermore, this lack of preparedness can disrupt residency training [25, 26] and manifest psychological effects [25, 26, 31]. To optimize MCE responses in the hospital/acute care setting, a disaster response protocol must be in place and simulated regularly. Whereas protocols have been emplaced in hospitals throughout the US [32], most have not been designed or simulated to account for RPs [9, 10, 14,15,16,17, 20, 21, 25, 26, 28]. The shortcomings of existing training are several, including communication barriers (among staff or between staff and patients,) lack of emphasis on triage, and a lack of definition of roles and responsibilities [17, 19, 20, 22, 28, 33, 34].

An organized, system-wide approach that provides clarity regarding staff roles and responsibilities contributes to successful disaster planning and recovery [33, 35]. Regular drills and simulations were recommended in physicians’ training by the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) in 2003 [36]. As rapid decision making and triage of patients are part of their everyday practices, surgeons, most particularly trauma surgeons, are assumed to occupy leadership roles during a MCE [7, 9, 10, 13, 17, 37]. This was conveyed explicitly by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) [39], who adopted (also in 2003) the position statement drafted by its Committee on Trauma, that “surgeons ought to attain an appropriate level of education and training in the unique principles and practices of disaster and mass casualty management, and to serve as role models in this field” [17, 33, 38, 39]. Nevertheless, surveys since then have shown not only that general surgery (GS) and emergency medicine (EM) RPs, who are trauma team members (TTMs) of hospitals, are underprepared [7, 9, 10, 13,14,15,16,17], but also that GS residents (GSRs) were even less prepared than EM residents (EMRs) [14, 17].

Based on the results of the several studies referenced above [7, 9, 10, 13,14,15,16,17], a questionnaire was distributed in two parts by us at our institution, an urban level I trauma center in New York City (NYC), the nation’s highest-risk area for MCEs [40, 41]. The first phase was designed to compare preparedness of GSRs to other TTMs (i.e., EMRs, EM physician assistants (EMPAs) and GS physician assistants (GSPAs.) In the second phase of this study, we evaluated the extent of disaster preparedness training for RPs across all specialties not represented on trauma teams as outlined above. We tested the hypothesis that, regardless of specialty, RPs are not familiar with the disaster response plans and protocols that are in place for MCEs and need additional training to ensure an effective and safe response in the event of such an event.

Methods

An electronic survey (Supplementary Information 1 and 2) was distributed in two phases to RPs, as well as to PDs/APDs (in the second phase only), of all accredited residency training programs across all specialties at our urban, university tertiary/quaternary medical center that serves as a regional referral center for injury care; non-accredited programs were excluded. Consisting of multiple-choice and free-response questions, the survey was distributed from May 26-October 13, 2018 for the first phase, then February 2-March 20, 2020 for the second phase.

Residency training PDs/APDs were recruited by e-mail using an internal directory and asked to participate. That recruitment e-mail message offered no incentive for participation. If there was no response after four requests, the program was considered a non-responder. After agreement, the survey was disseminated directly to RPs and PDs/APDs, or via the program coordinators of participating departments, with an introductory e-mail message that, by contrast, included a lottery for a modest cash prize as a means of compensation for the time devoted to participation. Follow-up e-mails were distributed using the contact information provided by PDs/APDs/program coordinators. All responses were kept anonymous.

The survey inquired as to demographic information including name and location of program, role of the respondent, postgraduate year (PGY) level, questions specific to MCE preparedness competencies addressed during training, and what teaching methodologies were used. The MCE preparedness core competencies assessed were those recommended by the National Standardized All-Hazard Disaster Core Competencies in Disaster Medicine [42]. Data were collected when participants accessed the e-mailed survey link. De-identified data were housed in a secure online database. The Research Electronic Data Capture database (REDCap®; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) was used under institutional license for data acquisition and analysis. The study was approved by the Committee on Human Rights in Research of Weill Cornell Medical College with waiver of informed consent (Protocol #1810019635).

Primary outcomes assessed were awareness of their institutional and departmental MCE plans with perceived degree of preparedness, and self-reporting of institutional MCE training and teaching during residency. Secondary outcomes assessed included differences in self-reporting comparing junior RPs (PGY-1, -2) vs. senior RPs (PGY-3+), and self-reporting of RPs’ awareness and preparedness between non-surgical specialties and surgical subspecialties. Additionally, PD/APD’s perceptions of appropriateness of time spent on MCE training, and reporting of barriers encountered were assessed.

To compare TTMs, including the EMRs and GSRs, with other medical specialty RPs we consolidated data from both phases of the survey and conducted a comprehensive analysis encompassing data from both surveys whenever applicable. The survey tool utilized initially differed slightly in that it was more concise, focusing on aspects such as awareness, knowledge of protocol, certainty regarding points of contact, responsibilities, and reporting procedures. In addition, the second phase assessed RPs' level of seniority and self-perceived levels of confidence. Furthermore, the assessment for advanced courses in the initial phase was limited to Advanced Trauma Life Support® (ATLS®, American College of Surgeons, Chicago, IL) and the Disaster Medical Education Program (DMEP, American College of Surgeons). Consequently, our comparative analysis between perceived levels of preparedness and certification in advanced courses was based solely on these two courses.

Statistical analysis

PDs/APDs were excluded from the analysis for the reported self-assessment of MCE plan-perceived awareness and preparedness (discussed in section II of Results). Descriptive results are reported as n (%) or median with interquartile range (IQR).

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare responses to Likert scale questions between groups. The Fisher exact test was used for multiple-group comparisons. All p values are two-sided with statistical significance evaluated at the 0.05 alpha level. Data were compiled using REDCap® software. All analyses were performed in R Version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

A total of 123 (74%) individuals responded to the first phase corresponding to a response rate of 74% (123/166), which was comprised of 79 EMRs and GSRs, and of 44 EMPAs and GSPAs. Among 21 programs surveyed in the second phase (excluding EM and GS), 17 (81%) programs responded to the survey, whereas 34% of individuals (129 /380) responded to the second survey, in which 117 respondents were RPs and 12 were PD/APDs. Combining the two surveys, the response rate was 46% (252/546.) Specialties represented by RPs and PD/APD’s (PAs excluded) (n = 208) were anesthesia (2 respondents, 1.0%), dermatology (2, 1.0%), EM (48, 23.1%), GS (31, 14.9%), internal medicine (50, 24.0%), neurology (9, 4.3%), obstetrics/gynecology (6, 2.9%), ophthalmology (1, 0.5%), oral/maxillofacial surgery and dentistry (4, 1.9%), otolaryngology-head and neck surgery (5, 2.5%), pathology (13, 6.2%), pediatrics (1, 0.5%), plastic surgery (5, 2.4%), psychiatry (15, 7.2%), radiation oncology (2, 1.0%), radiology-diagnostic (8, 3.8%), radiology-interventional (1, 0.5%), rehabilitation medicine (2, 1.0%), and urology (2, 1.0%). Among the respondents, 55 (26.4%) were junior RPs whereas 62 (29.8%) were senior RPs of these specialties. There were 12 respondent PDs/APDs (5.8% of respondents) (Supplementary Information 3.)

RPs’ self-assessment of MCE plan-perceived awareness and preparedness

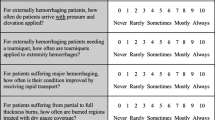

The survey assessed RPs’ awareness of institutional mass casualty response (yes, no, or unsure) through questions and responses shown in Table 1. Results from the combined surveys showed that 53% (n = 103) of RPs were unaware of such a plan. In our second-phase survey (that excluded TTMs,) 78% (n = 92) of respondents did not know or were unsure whether they were expected to contact someon.e and 73% (n=143) when combining surveys (including TTMs). Awareness of formal training was not assessed in the first-phase survey, but when non-TTM RPs were asked about awareness of formal MCE training offered by their program, 94% were unsure, and 81% reported no formal MCE training in the year prior (Table 2.) Despite the fact that TTM RPs are more likely to receive formal MCE training at our institution, a majority (68%, n = 134) of all RPs (including EMRs and GSRs) reported no formal MCE training over the past year (Table 1).

We asked specifically about advanced training courses related to trauma and disaster/MCE preparedness that were taken during residency training, some of which are mandatory. These courses included Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS, American Heart Association, Dallas, TX) and ATLS®. Whereas neither ACLS nor ATLS® are established components of DM preparedness, several aspects of these courses are relevant. Our consolidated findings revealed that 97% (n = 190) of respondents had completed ACLS, whereas 40% (n = 67) had undergone ATLS® training. Specific disaster/MCE preparedness courses were taken seldom. Advanced Disaster Medical Response (ADMR, American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, Chicago, IL), training was taken by 4% (n = 5) of participants, while Disaster Management and Emergency Preparedness (DMEP, American College of Surgeons), Advanced Disaster Life Support (ADLS®, National Disaster Life Support Foundation, Augusta, GA) and Fundamental Critical Care Support (FCCS®, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Mount Prospect, IL) were each taken by 3% (n = 4), although not by the same individuals.

Regarding self-assessment of perceived preparedness, responses were truncated similarly (Supplementary Information 4). Awareness of the existence of an MCE response plan across all residents showed a significant correlation with self-assessed preparedness, summarized in Table 2. However, differences in perceived preparedness between participants who were aware or unaware of the plan were slight. RPs who were aware of the plan (n = 93) had a “faint idea” of how knowledgeable they were about the plan (median 2.00 [IQR 1.00, 2.00]) compared to unaware RPs, who “had no idea” about how knowledgeable they were (median 1.00 [IQR 1.00, 1.00]) (p < 0.001) (Table 2.) A more robust relationship was identified between having knowledge of, or certainty about responsibilities during a MCE and possessing ATLS® or DMEP certification (Tables 3 and 4.) Median response for assessment of level of knowledge of MCE plan at institution is “I have a faint idea” (Likert 2) for ATLS®- or DMEP-certified RPs (median 2.00 [IQR1.00, 2.75]) vs. “I have no idea” for residents not certified (median 1.00 [IQR1.00, 1.00]) (p < 0.001). Similarly, the median response for assessment of level of certitude on responsibilities during a MCE is “slightly” (Likert 2) for ATLS- or DMEP-certified (median 2.00 [IQR 1.00, 2.75]) vs. “not at all” for residents not certified (median 1.00 [IQR 1.00, 1.00]) (p < 0.001).

Because confidence and level of seniority were not assessed in the first-phase survey, results from the analyses shown in Tables 5 and 6 reflect only non-TTM RPs. No differences were observed between RPs from non-surgical and surgical subspecialties regarding self-assessed preparedness. However, RPs from TTM subspecialties rated themselves more confident than non-TTM RPs (p = 0.031). Despite this, the median response in both groups indicated they were “not at all” confident (Table 5). Senior residents (PGY 3 +) rated themselves more prepared compared to junior residents regarding the hospital/institution’s MCE response (both, p < 0.05). However, the median response was “Not at all” in both groups. The level of seniority in training was not associated with participants’ self-assessment of preparedness (Table 6.)

RPs’ perceived lack of preparedness was assessed by the RPs perceived lack of training, which was evaluated with the following three questions: (1) In your opinion, how effectively has your DEPARTMENT prepared you for a MCE?; (2) In your opinion, how effectively has your HOSPITAL prepared you for a MCE?; (3) As a health care provider, how LIKELY do you think a MCE (natural or man-made) will happen in the next 5 years in the area where you are training? Consolidated possible responses are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The median perceived departmental effectiveness of MCE among all EMRPs was “somewhat effective” 2.00 [median 2.00 (IQR 1.50, 2.00)] whereas the median value for all other RPs across non-surgical and surgical specialties was “not at all” [median 1.00 (IQR 1.00, 2.00)] (p = 0.001). The median for perceived hospital preparedness was also “somewhat effective” [median 2.00 (IQR 1.00, 2.00), but with a smaller distribution, not significantly different from all other specialties where the median was “not at all” [median 1.00 (1.00, 2.00)] (p = 0.110) (Table 7.)

RPs’ perceived lack of training, was further evaluated using a 4-point Likert scale [1: A lot less than needed; 2: somewhat less than needed; 3: just the right amount; 4: somewhat more than needed]) with the following question in the second survey, excluding TTMs: “In your opinion, how would you rate the amount of time your residency program spends on mass casualty training?” Our analysis revealed that one-half of RPs (n = 58) estimated that the time spent for training was “somewhat less than needed,” and 42% (n = 49) of them estimated that it was “a lot less than needed” (Table 8.)

PD/APDs perception of MCE training importance and barriers encountered

The median response of “somewhat less time than needed” from PDs/APDs was similar to RPs’ responses regarding the amount of time devoted to MCE in residency training (Table 8.) Nevertheless, the importance of training during residency was reported as “slightly” for 44% (n = 4) of directorial respondents. Furthermore, 22% (n = 2) were of the opinion that MCE training was “not at all” important, whereas another 22% (n = 2) opined the training to be “somewhat” important and a single respondent believed that it was “moderately” important. No one reported MCE training as “extremely” important. Limitations to providing disaster education identified commonly by PDs/APDs were “limited time” (75%), “limited infrastructure” (41.6%), and “financial” barriers (41.6%). One director (8.3%) mentioned “other” unspecified barriers, such as a lack of information regarding the required training for residents in their specialty (Table 9.)

Discussion

In previous studies that highlight the lack of RPs’ disaster preparedness, the principal focus was on TTMs (e.g., EMRs [13,14,15,16,17, 20] and GSRs [7, 9, 14, 17, 20, 22, 25, 26]. Although trauma teams are first-responders during a MCE, scarce resources, patient volumes that exceed surge capacity, and special-needs populations, among other factors, may require early, active participation of RPs across all specialties. Therefore, there is a need to increase knowledge and awareness among all specialty residency programs.

To date, few studies have investigated RPs’ disaster preparedness in specialties other than GS and EM, such as anesthesia [21] and orthopedic surgery [18], although neither study conducted a comparative analysis with other specialties. Uddin et al. [28] addressed the existing gap in disaster and emergency preparedness training across various medical specialties. Whereas they acknowledged the need for improvement, their focus was primarily on specific fields such as surgery, anesthesiology, EM, pediatrics, and family medicine. In their study, they described a new curriculum specializing in preventive medicine, evaluating the progress of 15 residents who followed this curriculum. Given that RPs of all specialties constitute nearly 15% of the physician workforce in the US [43, 44], we emphasize the importance of incorporating MCE training across all specialties, rather than limiting it to selected ones. To our knowledge, this comprehensive approach has yet to be addressed in the existing literature.

Because RPs’ perceptions of preparedness across specialties have not been surveyed heretofore, we collaborated with all accredited residency training programs at our institution to assess the perceived level of preparedness of RPs, and to inquire about barriers faced by PDs/APDs to the implementation of MCE preparedness training. According to these results, further study can focus on more thorough educational needs assessments in MCE preparedness and care based on medical and surgical specialties, with the goals of developing curricula and advocating for changes to residency education relevant to the entire clinical enterprise and each specific department. Curricular content, teaching methodologies, and assessment tools may vary among the departments and reflect their needs.

Despite the vulnerability of NYC to MCEs [40, 41], and the disruption of training [25, 26] that would ensue, these data indicate that RPs across all specialties in a level I Trauma Center in NYC are underprepared. Physician awareness about an institutional MCE plan was not a strong predictor of preparedness, as the sole statistically different response was only slightly higher among physicians who reported awareness of a plan compared with those who were unaware. This suggests that physicians with awareness may still rely in times of disaster on directives from individuals that they know to contact. Moreover, subspecialty training did not predict self-assessment of preparedness (although sample sizes were small), nor did PGY seniority.

Previous studies indicate that EM PDs consider disaster preparedness as highly desired curricular additions [13, 16], but our surveyed PDs/APDs considered that, although “somewhat” less time than needed was devoted to MCE training in residency, it was only “slightly” important to add MCE training to their programs. This response highlights the contrast between PDs in specialties with a primary focus on disaster and emergency management, such as EM, and leaders from other disciplines less oriented toward this field. However, during MCEs, effective communication among specialties like EM, GS, and others becomes crucial. Certainly, the training and education of RPs as TTMs would differ from those in various other specialties.

Providing a more detailed description of the specific training objectives for residents in different specialties could potentially underscore the importance of this training for program leadership. It may prompt leaders to view the training as more than “slightly” important and perhaps recognize that the current allocation of time might be insufficient. As highlighted by one of the surveyed PDs in the open comment section of the survey, there is a recognized need for specific, detailed information regarding specific training requirements for residents in different specialties. Designing curricular content for various specialties is a major consideration. Even controlling for this, the responsibility for MCE training must be undertaken by the institution or department, and for all staff members, including trainees. Alternatively, once defined, outsourcing of training to a contracted third party, such as the National Training and Education Division from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) [45] is a possibility.

Available time for instruction was of particular concern among leaders. Although PDs/APDs acknowledged that MCE training in residency receives less attention than required, envisioning how this training can be integrated into an already “crowded” and demanding training environment that prioritizes clinical responsibilities is a challenge. One PD, in another comment, captured well this sentiment: “I would be in favor of instituting some MCE education, but it should be limited in depth/scope such that the objectives can be achieved in a limited amount of time. Remember that there is an opportunity cost associated with adding to the curriculum-some other worthy topic will necessarily receive less time.” This valid concern could be addressed through the utilization of new technology that was democratized quickly due to the pandemic, such as online access to courses and tests at more convenient times for trainees. Moreover, as Haug et al. [46] described the anticipated enhancements in quality of care from the utilization of artificial intelligence (AI), one must recognize the possibility that AI will become an integral part of physician training sooner than anticipated.

“Finance” was cited as a barrier second only to “time.” Lack of governmental funding, whether in the US [47] or globally [48], may contribute to the lack of hospital staff training for MCEs. Technological advances (e.g., simulation) could be an approach to reduce the cost of MCE preparedness exercises [34, 37, 49]. Whereas in-person training with medical role players remains preferable, the emergence of AI could offer future opportunities for simulation, enabling trainees to practice and validation of some MCE training components in simulation centers. Other components of MCE training, such as triage, decontamination, or resource allocation, could be incorporated into didactic course segments or mandatory hospital training, in parallel to utilization of machine learning technology [50]. Other options that could be considered would be a centralized course for parts common to all specialties as part of GME orientation training when starting residency.

Crucial to the wider availability of MCE/DM training will be widespread recognition that it, too, is a core component of training for more than just GS and EM specialists [27, 29, 37, 47]. Creating plans of action tailored to each specialty, not just to EM [13, 15, 16, 42], combined with identification of impediments to disaster preparedness implementation will help convey the need to department chairs, hospital administration, governmental institutions, payors, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME.) Drawing from the training disruption experienced as residency graduates during the pandemic, Rojek et al. [51] emphasized further the need to expand residency education beyond traditional bedside clinical care and advocated for a broader curriculum in residency training, encompassing proficiency with the electronic health record, collaboration with specialists, and navigation skills within complex healthcare systems. They proposed collaborative efforts among residency programs, health systems, and regulatory bodies such as the ACGME to integrate RPs into system-level initiatives aiming at better preparation of residents for the complexities of modern healthcare delivery, including MCE. This integration would involve participation on committees, quality improvement projects, and other initiatives aimed at enhancing healthcare cost-effectiveness, equity, quality, and structural innovation. Nevertheless, successful implementation of an amalgam of orientation, didactics, frequent drills, and workshops that emphasize roles, responsibilities, triage, and effective communication under high-stress conditions will also require proper evaluation tools [42, 52].

There are several limitations to this study. These data were collected before the outbreak of COVID-19, which reached NYC in March 2020. We can speculate that prior to being exposed to severe shortages of resources generated by the pandemic, healthcare providers in most hospitals did not conflate the necessity for MCE training for multiple trauma events with other events that also generate a need for resource re-allocation, including re-assignment of duties. Given the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training [53, 54], it is possible that PDs/APDs would report a different answer than “slightly” when gauging the importance for MCE training during residency. As mentioned previously, residency graduates have underscored the need to address training disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, including staffing shortages, virtual visits supplanting in-person learning experiences, and high patient census [51]. Thus, it is possible that both PD/APDs and RPs would have higher response rates to this survey due to the urgent need to address these residency training gaps.

Another limitation is the relatively low response rates from PDs/APDs and non-TTM RPs, making it difficult to generalize the data across institutions and specialty types. A self-selected response group (such as herein) may introduce bias if responding programs/participants represent those with the most (or least) comfort with and interest in DM, but this is a matter of speculation. We did not assess specific indicators of what existing training encompasses.

The combination of two similar but not identical survey instruments introduced limitations from a statistical standpoint. First, measurement bias may be introduced, as the alignment of responses for analytic purposes may not capture fully the nuances of the constructs being assessed. Moreover, the temporal gap between survey phases might raise concern about the comparability of the data due to potential changes of population characteristics over time, although turnover is inherent to residency training. The study design precluded the application of advanced statistical techniques, such as multivariable analyses or structural equation modeling.

Conclusion

Although MCE preparedness is garnering increased attention and a variety of educational tools exist today to teach DM in US residency programs, trainees across all programs at a university level I trauma center remain unaware and unprepared for a disaster in a metropolitan area, comprising an estimated 20 million individuals, that has already been targeted for multiple MCEs [2, 6, 19, 40, 41, 55]. This survey highlights the need and opportunity for the creation of an educational model in DM, not only for TTMs but also for RPs across all medical specialties.

Data availability

The materials and data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

National Association of State EMS Officials. The EMS Data Managers Council. Extended Definition Document NEMSIS/NHTSA 2.2.1 Data Dictionary. https://nemsis.org/media/nemsis_v2/documents/Data_Managers_Council_-_Data_Definitions_Project_Final_Ve.pdf. Accessed 19 Dec 2023.

Eachempati SR, Flomenbaum N, Barie PS. Biological warfare: current concerns for the health care provider. J Trauma. 2002;52:179–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-200201000-00034.

Mace SE, Sharma A. Hospital evacuations due to disasters in the United States in the twenty-first century. Am J Disaster Med. 2020;15:7–22. https://doi.org/10.5055/ajdm.2020.0351.

Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). The human cost of disasters: an overview of the last 20 years 2000–2019. https://www.undrr.org/publication/human-cost-disasters-overview-last-20-years-2000-2019. Accessed 23 Dec 2022.

Bashir ©U. COP28: The climate crisis is also a health crisis. In: UN News. 3 Dec 2023. https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/12/1144292. Accessed 28 Dec 2023.

Stamell EF, Foltin GL, Nadler EP. Lessons learned for pediatric disaster preparedness from September 11, 2001: New York City trauma centers. J Trauma. 2009;67:S84–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3181adfb81.

Ciraulo DL, Frykberg ER, Feliciano DV, Knuth TE, Richart CM, Westmoreland CD, et al. A survey assessment of the level of preparedness for domestic terrorism and mass casualty incidents among Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma members. J Trauma. 2004;56:1033–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000127771.06138.7d.

Eachempati SR, Mick S, Barie PS. The impact of the 2003 blackout on a level 1 trauma center: Lessons learned and implications for injury prevention. J Trauma. 2004;57:1127–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000141891.51102.28.

Galante JM, Jacoby RC, Anderson JT. Are surgical residents prepared for mass casualty incidents? J Surg Res. 2006;132:85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2005.07.031.

Ciraulo DL, Barie PS, Briggs SM, Bjerke HS, Born CT, Capella J, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma: Disaster and Medical Special Operations Committee, (DMSOC), et al. An update on the surgeons’ scope and depth of practice to all hazards emergency response. J Trauma. 2006;60:1267–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000220665.03167.09.

Chokshi NK, Behar S, Nager AL, Dorey F, Upperman JS. Disaster management among pediatric surgeons: preparedness, training and involvement. Am J Disaster Med. 2008;3:5–14.

Trunkey DD. US trauma center preparation for a terrorist attack in the community. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2009;35:244–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-009-9901-7.

Katzer R, Cabanas JG, Martin-Gill C, SAEM Emergency Medical Services Interest Group. Emergency medical services education in emergency medicine residency programs: a national survey. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:174–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01274.x.

Dennis AJ, Brandt M-M, Steinberg J, Qureshi S, Burns JB, Capella J, et al. Are general surgeons behind the curve when it comes to disaster preparedness training? A survey of general surgery and emergency medicine trainees in the United States by the Eastern Association for the Surgery for Trauma Committee on Disaster Preparedness. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:612–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e318265c9d9.

Sheikh S, McCormick LC, Pevear J, Adoff S, Walter FG, Kazzi ZN. Radiological preparedness-awareness and attitudes: a cross-sectional survey of emergency medicine residents and physicians at three academic institutions in the United States. Clin Toxicol. 2012;50:34–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2011.637047.

Sarin RR, Cattamanchi S, Alqahtani A, Aljohani M, Keim M, Ciottone G. Disaster Education: a survey study to analyze disaster medicine training in emergency medicine residency programs in the United States. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32(4):368–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X17000267.

Russo RM, Galante JM, Jacoby RC, Shatz DV. Mass casualty disasters: who should run the show? J Emerg Med. 2015;48:685–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.069.

Tobert D, von Keudell A, Rodriguez EK. Lessons from the Boston Marathon bombing. An orthopaedic perspective on preparing for high-volume trauma in an urban academic center. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(Suppl 10):S7–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000000413.

Cushman JG, Pachter HL, Beaton HL. Two New York City hospitals’ surgical response to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack in New York City. J Trauma. 2003;54:147–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-200301000-00018.

Brevard SB, Weintraub SL, Aiken JB, Halton EB, Duchesne JC, McSwain NE Jr, et al. Analysis of disaster response plans and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: lessons learned from a level I trauma center. J Trauma. 2008;65:1126–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e318188d6e5.

Hayanga HK, Barnett DJ, Shallow NR, Roberts M, Thompson CB, Bentov I, et al. Anesthesiologists and disaster medicine: a needs assessment for education and training and reported willingness to respond. Anesth Analg. 2017;124:1662–9. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002002.

Mahoney EJ, Harrington DT, Biffl WL, Metzger J, Oka T, Cioffi WG. Lessons learned from a nightclub fire: Institutional disaster preparedness. J Trauma. 2005;58:487–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000153939.17932.e7.

Smith CP, Cheatham ML, Safcsak K, Emrani H, Ibrahim JA, Gregg M, et al. Injury characteristics of the Pulse Nightclub shooting: lessons for mass casualty incident preparation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88:372–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000153939.17932.e7.

Mohr NM, Harland KK, Krishnadasan A, Eyck PT, Mower WR, Willey J, Project COVERED Emergency Department Network, et al. Diagnosed and undiagnosed COVID-19 in US emergency department health care personnel: a cross-sectional analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78:27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.12.007.

Matthews JB, Blair PG, Ellison EC, Elster EA, Nagler A, Schwaitzberg SD, et al. Checklist framework for surgical education disaster plans. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233(4):557–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.06.015.

Joshi A, Abdelsattar J, Castro-Varela A, Wehrle CJ, Cullen C, Pei K, et al. Incorporating mass casualty incidents training in surgical education program. Glob Surg Educ. 2022;1:17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-022-00018-z.

Persoff J, Ornoff D, Little C. The role of hospital medicine in emergency preparedness: a framework for hospitalist leadership in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. J Hosp Med. 2018;13:713–8. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3073.

Uddin SG, Barnett DJ, Parker CL, Links JM, Alexander M. Emergency preparedness: addressing a residency training gap. Acad Med. 2008;83:298–304. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181637edc.

Tankel J, Einav S. Preparing for mass casualty events despite COVID-19. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128:e104–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.11.012.

Hachiya M, Tominaga T, Tatsuzaki H, Akashi M. Medical management of the consequences of the Fukushima nuclear power plant incident. Drug Dev Res. 2014;75:3–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ddr.21161.

Havron WS 3rd, Safcsak K, Corsa J, Loudon A, Cheatham ML. Psychological effect of a mass casualty event on general surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:e74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.07.021.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). NIMS Implementation for Hospitals and Health Care Systems. Fact Sheet. 2006. https://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nims/imp_hos_fs.pdf. Accessed 19 Dec 2022.

Moran ME, Zimmerman JR, Chapman AD, Ballas DA, Blecker N, George RL. Staff perspectives of mass casualty incident preparedness. Cureus. 2021;13: e15858. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.15858.

Gardner AK, DeMoya MA, Tinkoff GH, Brown KM, Garcia GD, Miller GT, et al. Using simulation for disaster preparedness. Surgery. 2016;160:565–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.03.027.

Savoia E, Lin L, Bernard D, Klein N, James LP, Guicciardi S. Public health system research in public health emergency preparedness in the United States (2009–2015): actionable knowledge base. Am J Publ Health. 2017;107:e1–6. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304051.

Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (DHS/PHS). Training future physicians about weapons of mass destruction: Report of the expert panel on bioterrorism education for medical students. 2003. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED482377.pdf. Accessed 8 Apr 2024.

Gabbe BJ, Veitch W, Mather A, Curtis K, Holland AJA, Gomez D, et al. Review of the requirements for effective mass casualty preparedness for trauma systems. A disaster waiting to happen? Br J Anaesth. 2022;128:e158–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.10.038.

Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons. Statement on disaster and mass casualty management. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:855–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00808-1.

Frykberg ER. Disaster and mass casualty management: a commentary on the American College of Surgeons position statement. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:857–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00809-3.

Marquez M, Patel P, Raphael M, Morgenthau BM. The danger of declining funds: Public health preparedness in NYC. Biosecur Bioterror. 2009;7:337–45. https://doi.org/10.1089/bsp.2009.0048.

New York State Homeland Security and Emergency Services. New York State Emergency Management Association. New York State mass fatality management resource guide. 2020. https://www.dhses.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2021/09/nys-mass-fatality-resource-guide-final.pdf. Accessed 27 Dec 2022.

Schultz CH, Koenig KL, Whiteside M, Murray R, National Standardized All-Hazard Disaster Core Competencies Task Force. Development of national standardized all-hazard disaster core competencies for acute care physicians, nurses, and EMS professionals. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59:196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.09.003.

Lin GL, Ge TJ, Pal R. Resident and fellow unions: collective activism to promote well-being for physicians in training. JAMA. 2022;328:619–20. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.12838.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. About us: ACGME by the numbers. Academic year 2022–2023 overview. https://www.acgme.org/overview/. Accessed 3 Dec 2023.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). First responder training system. https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/national-preparedness/training. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Haug CJ, Drazen JM. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in clinical medicine, 2023. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(13):1201–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2302038.

Champion HR, Mabee MS, Meredith JW. The state of US trauma systems: public perceptions versus reality-implications for US response to terrorism and mass casualty events. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;206:951–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.019.

Dell’Era S, Hugli O, Dami F. Hospital disaster preparedness in Switzerland over a decade: a national survey. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019;13:433–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2018.59.

Tallach R, Einav S, Brohi K, Abayajeewa K, Abback P-S, Aylwin C, et al. Learning from terrorist mass casualty incidents: a global survey. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128:e168–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.10.003.

Loftus TJ, Tighe PJ, Filiberto AC, Efron PA, Brakenridge SC, Mohr AM, et al. Artificial intelligence and surgical decision-making. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:148–58. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4917.

Rojek AE, Schiller PT. Residency training in the COVID-19 pandemic-addressing the need for systems-based education. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3: e223023. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3023.

Verheul ML, Dückers MLA, Visser BB, Beerens RJ, Bierens JJ. Disaster exercises to prepare hospitals for mass-casualty incidents: does it contribute to preparedness or is it ritualism? Prehosp Disaster Med. 2018;33:387–93. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X18000584.

Awadallah NS, Czaja AS, Fainstad T, McNulty MC, Jaiswal KR, Jones TS, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family medicine residency training. Fam Pract. 2021;38(Suppl 1):i9–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmab012.

Chen SY, Lo HY, Hung SK. What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training: a systematic review and analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:618. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03041-8.

Feeney JM, Goldberg R, Blumenthal JA, Wallack MK. September 11, 2001, revisited: a review of the data. Arch Surg. 2005;140:1068–73. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.140.11.1068.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Catherine Ng, Data Assistant-Weill Cornell Medicine Clinical & Translational Science Center (CTSC), and Michelle Demetres, assistant librarian-Weill Cornell Samuel J. Wood Library, for their invaluable assistance. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, National Institutes of Health, under award UL1TR002384.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Voza, F.A., Gupta, A., Rossen, N. et al. Multispecialty resident physicians’ perceived preparedness for mass casualty events (MCEs) at an urban level I trauma center prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) era. Global Surg Educ 3, 78 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-024-00252-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-024-00252-7