Abstract

Purpose

Interprofessional collaboration is essential in surgery, but health professions students have limited opportunities for interprofessional education (IPE) during training in authentic patient-care settings. This report describes the development and evaluation of a clinical interprofessional elective in otolaryngology for medical (MD) and nurse practitioner (NP) students.

Methods

MD and NP students were paired together on an inpatient otolaryngology consult service for one- or two-week rotations designed to promote interprofessional learning objectives. Students worked with different professions essential to the care of patients with voice, airway, and swallowing conditions, including surgeons, advanced practice providers, speech-language pathologists, nurses, and respiratory therapists. Students completed written daily reflections about their experiences and pre- and post-rotation surveys to assess comfort with course learning objectives. Paired t-tests and Cohen’s d effect sizes were used to compare pre/post responses, and thematic analysis was used to analyze all narrative data.

Results

Fourteen students (8 MD, 6 NP) students completed the rotation. All participants reported significant improvements on all learning objectives (p < 0.05) with large effect sizes (Cohen’s d range: 1.2–2.9), including their understanding of the responsibilities of each interprofessional team member. Participants described three overarching themes that characterized their learning experiences and supported the learning objectives: appreciation for interprofessional patient care, benefits of learning with an interprofessional peer, and clinician role modeling of effective interprofessional communication.

Conclusions

IPE can be successfully integrated into a clinical surgical rotation and enhance students’ understanding of the benefits of and strategies for effective interprofessional collaboration. The elective can serve as a model for IPE rotations in other surgical subspecialties and be extended to include students across the continuum of health professions education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interprofessional collaboration and teamwork are essential to patient care in surgery. Although teamwork can take many forms, true interprofessional practice (IPP) is an intentional approach to patient care that occurs when two or more professionals effectively collaborate with a full understanding of each member’s roles and responsibilities and the value every member contributes [1,2,3]. Across various surgical specialties, IPP has been shown to improve patient outcomes, such as reduced adverse events, length of stay, and readmissions [4,5,6].

In line with IPP, interprofessional education (IPE) helps health professions students develop fundamental skills and knowledge to work in these interprofessional teams. According to the World Health Organization, IPE “occurs when students from two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes” [2]. The goal of IPE as laid out by the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) is to develop competency for interprofessional collaboration, which encompasses the topics of values and ethics, roles and responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and teams and teamwork [7]. IPE programs have been developed across various disciplines [8,9,10], and health professions students have reported positive impacts of IPE on their perceptions of interprofessional teamwork and shared problem-solving [11].

While many health professions have integrated IPE into training, initiatives in surgical specialties have been limited. The prior work that does exist has largely focused on case studies and simulation [12,13,14,15]. Though effective and safe, simulation is often unable to replicate the complex dynamics that occur when multiple members of the care team interact with patients and their caregivers in clinical practice. Alternatively, workplace-based IPE offers unique educational opportunities afforded by authentic patient care [16], but few formal curricula have been described in surgery, specifically in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery (OHNS). Therefore, we sought to address these gaps by designing an interprofessional clinical elective in otolaryngology for health professions students to further develop IPE competencies in a real-world environment. The purposes of this study are to (1) describe the development and evaluation of a clinical IPE elective in a surgical subspecialty for health professions students and (2) examine the impact of this elective on student knowledge and attitudes toward IPP.

Materials and methods

Curriculum development

At our institution, all health professions students participate in a longitudinal, blended IPE curriculum during their pre-clinical years. During the clinical year, medical (MD) students typically select two-week clinical electives for career exploration and clinical skill development; these electives were temporarily shortened to one week during Fall 2020 due to the impacts from COVID-19. Nurse practitioner (NP) students participate in clinical electives integrated throughout their classroom time, which can be scheduled on a case-by-case basis.

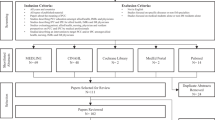

Two interprofessional faculty members (one surgeon and one NP) in the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery developed the elective based on Kern’s six-step approach for curriculum development in medical education [17]. The initial needs assessment revealed that, at the time of curriculum design, only three clinical IPE electives were offered at the institution, none of which were within a surgical specialty. To remedy this gap, the faculty chose the inpatient otolaryngology consult service as the clinical site, which already had an established interprofessional patient care team. The overarching goal of the elective was to expose MD and NP students to the interprofessional care of hospitalized surgical patients. The faculty collaborated with clinical stakeholders (surgeons, advanced practice providers (APPs), speech-language pathologists (SLPs), respiratory therapists (RTs), and nurses) to develop course learning objectives. Three of the learning objectives were specific to interprofessional core competencies [7], and two were specialty-specific with educational activities and evaluation methods selected to align with the learning objectives (Fig. 1). The activities were designed to allow MD and NP students not only to work together as peers but also to learn from interprofessional team members. A sample weekly schedule is shown in Fig. 2.

To facilitate learning objectives 1 (interprofessional roles and responsibilities) and 2 (peer collaboration), NP and MD students viewed a short video introducing all the team members, and the pairs spent dedicated time with all members of the interprofessional team. With the surgical team (physicians and APP), students presented patients on morning rounds and evaluated new patient consults. With the rapid response team (critical care nurse and RT), students responded to codes and rounded on patients with airway concerns. With SLPs, they observed both fluoroscopic and endoscopic swallowing exams for patients with dysphagia as well as bedside voice assessments for dysphonia. To help consolidate their diverse experiences, students submitted daily written reflections (Table 1A) through Qualtrics (Qualtrics Inc., Provo, UT). To meet learning objective 3 (interprofessional communication), students participated in weekly “trach rounds,” an established practice where the entire interprofessional team meets to discuss and evaluate patients with surgical airways (e.g., tracheostomies or laryngectomies). MD and NP student pairs observed rounds and wrote reflections on their observations of interprofessional teamwork and communication (Table 1B). Finally, to meet learning objective 4 (head and neck exam skills), students viewed a pre-recorded video on head and neck anatomy and examination, and the faculty leads facilitated a weekly hour-long skills session, where students practiced head and neck exam and basic flexible nasolaryngoscopy skills.

Course grades were pass-fail, based on the completion of the activities. MD students registered for the rotation as part of their normal elective process, while NP students were recruited by their school administrators according to their interests. This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board as exempt.

Participants

Of 16 available spots, 14 students (eight MD and six NP) completed the elective from September 2020 to May 2021. Eight students completed a one-week rotation from September to December 2020, and six students completed a two-week rotation from January to May 2021. There were seven unique MD/NP student pairs.

Program evaluation

Focusing on the first two levels of the Kirkpatrick evaluation framework [18], we assessed student reactions and learning through deidentified pre- and post-rotation surveys and written responses to the various reflections and open-ended survey questions (prompts in Table 1). On pre- and post-surveys, students rated their comfort with each rotation objective using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = extremely uncomfortable to 5 = extremely comfortable). Statistical analysis included paired t-tests and Cohen’s d measure of effect size to assess pre- and post-rotation differences. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05. Effect sizes of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were considered small, medium, and large, respectively [19]. Only complete pre- and post-data were included.

We conducted thematic analysis to develop themes from the written responses to the open-ended survey questions [20]. Coding proceeded iteratively in stages. After reviewing the narrative data, the first author generated initial codes using the learning objectives as a guide, forming a framework that was then applied to the entire dataset. Two researchers then reviewed the codes and developed themes together through constant comparison and discussion.

Results

MD and NP students exhibited significant improvements in self-reported comfort in all learning objectives with large effect sizes (Table 2). The greatest increases in interprofessional learning objectives included students’ comfort describing the roles and responsibilities of APPs from a mean (± SD) of 2.4 (± 1.1) pre-rotation to 4.2 (± 0.6) post-rotation (p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.0) and SLPs from 3.0 (± 1,2) pre-rotation to 4.7 (± 0.5) post-rotation (p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.8). Students also expressed improvement in identifying effective communication strategies between interprofessional team members, from 3.8 (± 0.6) pre-rotation to 4.5 (± 0.5) post-rotation (p = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 1.2). When comparing participants who participated in a one-week rotation versus a two-week rotation, no statistically significant differences in either pre-rotation or post-rotation self-ratings on learning objectives were found between the two groups (p > 0.05).

From the narrative data in written reflections and post-rotation surveys, we identified three overarching themes that characterized student learning experiences on the rotation: (1) value of an interprofessional approach to patient care in surgery, (2) benefits of working with a learner from another profession, and (3) role modeling of effective interprofessional communication in the workplace. Theme descriptions and representative quotes in are depicted in Table 3. In line with learning objective 1, theme 1 demonstrated that students developed a deeper insight into the role of each interprofessional team member, including how each member contributed their unique knowledge and training to the team. Aligned with objective 2, theme 2 revealed that the NP and MD students learned not only more about each other’s training programs but also one another’s clinical knowledge and skillsets. Finally, reflecting learning objective 3, theme 3 showed that students observed and recognized respectful communication between interprofessional colleagues and its importance in planning and coordinating a patient’s care. The post-rotation survey also requested student suggestions for improvement, which included making the experience longer and building additional flexibility to tailor schedules to focus on areas of interest or participate in outpatient laryngology clinics. Participants from both one-week and two-week rotations both commented that a longer rotation could be beneficial.

Discussion

We successfully designed and implemented an interprofessional clinical rotation for NP and MD students in a surgical subspecialty. The students developed a deeper understanding of the clinical expertise of various professions and how they complement one another. Similar to reports of other clinical interprofessional experiences [21, 22], our students found the elective a positive learning experience that helped them gain insight into how the different viewpoints of each interprofessional team member shaped patient management and learn about their interprofessional peers’ skills and knowledge. Students also reported increased comfort in their clinical knowledge and skills alongside improvements in interprofessional competencies, demonstrating that IPE can be seamlessly and effectively integrated into clinical education in surgery for health professions students.

IPE is an essential precursor to effective IPP. To successfully work in teams to manage the complex medical and psychosocial needs of surgical patients, IPE must be incorporated into early foundational health professions education and continued throughout one’s career [23]. These opportunities can not only provide foundational knowledge, skills, and attitudes for students to incorporate into clinical practice but also break down the silos that separate the training of different health professions [24]. As such, a clinical IPE rotation that allows students to participate in authentic interprofessional teamwork and collaboration in the workplace can serve as an important introduction to IPP. Although studies show that the workplace offers unique interprofessional learning opportunities [25, 26], this approach has been underutilized in surgery. This curriculum helps fill this gap and can serve as a guide for others to develop similar IPE experiences in surgical disciplines.

In developing this program, we integrated educational practices grounded in several theoretical domains that can be transferred across surgical fields. First, our interprofessional team already had a close working relationship, creating a strong community of practice as a context for learning [26, 27]. Second, although learners had a schedule, they were also given flexibility to select additional activities on which to focus. In line with self-determination theory, students could tailor their learning, which has been shown to enhance learning outcomes [28]. Third, the daily reflection exercises were founded on the principles of reflective practice, which has been shown to improve engagement in learning complex content [29,30,31,32]. We found that it was feasible to incorporate these elements into the rotation, which also supported the evaluation of our learners.

We did not find any meaningful differences in self-reported learning outcomes between participants who completed a one-week versus a two-week rotation. While the study was not designed to compare the learning outcomes between different durations of an IPE rotation, our results suggest that either a one-week versus two-week rotation can be viable and effective, depending on the institution’s resources and students’ schedules. In addition, feedback from students in both one-week and two-week groups suggests that a longer rotation would also be of interest when possible.

A unique challenge of implementing the interprofessional rotation involved coordinating different MD and NP student schedules, as each school incorporated clinical rotations differently into their overarching curriculum. Therefore, for those interested in developing similar electives, we emphasize the importance of having interprofessional faculty leadership to facilitate integration of the elective into the school curricula and clinical workplace. Joint leadership can also help model collaborative interprofessional principles and ensure that the perspectives of the two health professions learner groups are represented. Other challenges included the unanticipated schedule changes due to the pandemic and the unpredictability of the week-to-week clinical volume, which contributed to an already variable learning environment. However, we did not find strong differences in outcomes between the students who participated in one-week vs two-week rotations.

Limitations of this study include its small sample size as well as its short-term implementation and follow-up. Still, our study demonstrates that even a short clinical IPE rotation is feasible and effective, illustrating the potential of such a program in health professions education in a surgical subspecialty. We acknowledge that IPE is a lifelong process; therefore, students cannot be expected to have mastered the principles of IPP during this time. This rotation, however, most importantly succeeded in helping students recognize the value of IPP and think intentionally about how each profession can contribute to patient care, providing an essential foundation for future IPP. Surgical educators can continue to build on the framework of this curriculum and expand the design to include learners from other health professions, such as pharmacy, physical and occupational therapy, respiratory therapy, speech-language pathology, and audiology.

Conclusion

Interprofessional collaboration is essential to caring for surgical patients. To better prepare future healthcare providers for interprofessional practice, IPE can be effectively incorporated into the clinical curricula of health professions students, enhancing not only students’ clinical skills but also their knowledge and perceptions of other health professions. The IPE curriculum described in this paper can serve as a model for other surgical educators to develop workplace-based IPE to further prepare our students for interprofessional collaboration and practice.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

References

What is Interprofessional Practice? n.d. https://www.asha.org/practice/ipe-ipp/what-is-ipp/ (Accessed June 17, 2022).

World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. World Health Organization; 2010.

Rivers NJ, Maira C, Wise J, Hapner ER. The impact of referral source on voice therapy. J Voice. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.12.051.

Welton C, Morrison M, Catalig M, Chris J, Pataki J. Can an interprofessional tracheostomy team improve weaning to decannulation times? A quality improvement evaluation. Can J Respir Ther CJRT Rev Can Ther Respir RCTR. 2016;52:7–11.

Arana M, Harper L, Qin H, Mabrey J. Reducing length of stay, direct cost, and readmissions in total joint arthroplasty patients with an outcomes manager-led interprofessional team. Orthop Nurs. 2017;36:279. https://doi.org/10.1097/NOR.0000000000000366.

Urisman T, Garcia A, Harris HW. Impact of surgical intensive care unit interdisciplinary rounds on interprofessional collaboration and quality of care: Mixed qualitative–quantitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;44:18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.07.001.

Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 2016 Update 2016:22

McCave EL, Aptaker D, Hartmann KD, Zucconi R. Promoting affirmative transgender health care practice within hospitals: an IPE standardized patient simulation for graduate health care learners. MedEdPORTAL n.d.;15:10861. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10861.

Fishman SM, Copenhaver D, Mongoven JM, Lorenzen K, Schlingmann E, Young HM. Cancer pain treatment and management: an interprofessional learning module for prelicensure health professional students. MedEdPORTAL n.d.;16:10953. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10953.

Kesselheim JC, Stockman LS, Growdon AS, Murray AM, Shagrin BS, Hundert EM. Discharge day: a case-based interprofessional exercise about team collaboration in pediatrics. MedEdPORTAL n.d.;15:10830. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10830.

Dyess AL, Brown JS, Brown ND, Flautt KM, Barnes LJ. Impact of interprofessional education on students of the health professions: a systematic review. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2019;16:33. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2019.16.33.

Paull DE, DeLeeuw LD, Wolk S, Paige JT, Neily J, Mills PD. The effect of simulation-based crew resource management training on measurable teamwork and communication among interprofessional teams caring for postoperative patients. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2013;44:516–24. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20130903-38.

Paige JT, Garbee DD, Kozmenko V, Yu Q, Kozmenko L, Yang T, et al. Getting a head start: high-fidelity, simulation-based operating room team training of interprofessional students. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:140–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.09.006.

George KL, Quatrara B. Interprofessional simulations promote knowledge retention and enhance perceptions of teamwork skills in a surgical-trauma-burn intensive care unit setting. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2018;37:144. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000301.

Bauman B, Kernahan P, Weinhaus A, Walker MJ, Irwin E, Sundin A, et al. An Interprofessional senior medical student preparation course: improvement in knowledge and self-confidence before entering surgical training. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021;12:441–51. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S287430.

Baerheim A, Raaheim A. Pedagogical aspects of interprofessional workplace learning: a case study. J Interprofessional Care. 2019;34:59–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1621805.

Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. Annals Int Med. 2015. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-130-10-199905180-00028.

Kirkpatrick D. Evaluating Training Programs: the Four Levels. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler; n.d.

Cohen J. The concepts of power analysis BT - statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (Revised Edition). Stat Power Anal Behav Sci 1988:1–17.

Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 2020;42:846–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030.

Hallin K, Kiessling A. A safe place with space for learning: Experiences from an interprofessional training ward. J Interprof Care. 2016;30:141–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1113164.

Stilos K, Daines P, Moore J. An interprofessional education programme for medical learners during a one-month palliative care rotation. Int J Palliat Nurs 2016;22:186–92. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2016.22.4.186.

Barr H, Koppel I, Reeves S, Hammick M, Freeth D. Effective interprofessional education: assumption, argument and evidence. London: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2015.

Margalit R, Thompson S, Visovsky C, Geske J, Collier D, Birk T, et al. From professional silos to interprofessional education: campuswide focus on quality of care. Qual Manag Health Care. 2009;18:165–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/QMH.0b013e3181aea20d.

Nisbet G, Lincoln M, Dunn S. Informal interprofessional learning: an untapped opportunity for learning and change within the workplace. J Interprof Care. 2013;27:469–75. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.805735.

Nisbet G, Dunn S, Lincoln M. Interprofessional team meetings: opportunities for informal interprofessional learning. J Interprof Care. 2015;29:426–32. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1016602.

Wenger E. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 1998. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932.

Williams GC, Saizow RB, Ryan RM. The importance of self-determination theory for medical education. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 1999;74:992–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199909000-00010.

Clark PG. Reflecting on reflection in interprofessional education: Implications for theory and practice. J Interprof Care. 2009;23:213–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820902877195.

Winkel AF, Yingling S, Jones A-A, Nicholson J. Reflection as a learning tool in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:430–9. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-16-00500.1.

Helyer R. Learning through reflection: the critical role of reflection in work-based learning (WBL). J Work-Appl Manag. 2015;7:15–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWAM-10-2015-003.

Richard A, Gagnon M, Careau E. Using reflective practice in interprofessional education and practice: a realist review of its characteristics and effectiveness. J Interprof Care. 2019;33:424–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1551867.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Matthew Russell, MD and Regina Gould, PA-C for their teaching efforts and Patricia O’Sullivan, EdD for manuscript edits.

Funding

This work was supported by the Interprofessional Clinical Opportunities Grant through the UCSF Program for Interprofessional Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, E.K., Krauter, R. & Zhao, N.W. Promoting interprofessional education in surgery: development and evaluation of a clinical curriculum. Global Surg Educ 2, 87 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-023-00166-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-023-00166-w