Abstract

Research in calling has increased in recent years, yet the lack of attention on the managerial antecedents and prosocial behavioral outcome of calling orientation presents key challenges to meet the needs of the organizational management. Based on the social impact theory, this study examined the predicting effects of a team leader’s transformational leadership on followers’ calling orientation, and the effects of team members’ calling orientation on their helping behaviors at work. The experimental study and the survey were conducted to test the hypotheses. The results showed that a leader’s transformational leadership was positively related to followers’ calling orientation. A leader’s organizational status moderated the relationship between a leader’s transformational leadership and followers’ calling orientation. Followers’ calling orientation was positively related to their helping behaviors at work. The results provide important implications for cultivating employees’ calling orientation in the workplace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Pursuing the work meaning is the basic motivation of human beings. Calling orientation has been described as the “strongest”, most “extreme” or “deepest” route to truly meaningful work (Dik and Shimizu 2019). As calling orientation can be cultivated or developed, interest in the antecedents of calling orientation increased dramatically in recent years. For example, a longitudinal study showed that musicians with higher behavioral involvement and social comfort experienced higher levels of sense of calling (Dobrow 2013). The longitudinal study by Zhang et al. (2018) found that the authenticity can significantly and positively predict calling orientation. A three-wave longitudinal study by Dalla Rosa et al. (2019) found that clarity of professional identity, engagement in learning activities and social support predicted calling orientation. Recently, an empirical study showed that the daily number of code blue events was positively related to daily occupational calling for nurses (Zhu et al. 2020). Although the prior studies provided us with meaningful insight into understanding the antecedents of calling orientation, the antecedents of calling orientation are still limited, and the needs of the organization and management couldn’t be met (Lysova et al. 2019; Thompson and Bunderson 2019). Scholars have called for future research to continue to explore the antecedents of calling orientation (Duffy and Dik 2013; Lysova et al. 2019; Thompson and Bunderson 2019).

Sturges et al. (2019) recently found that the emergence of calling orientation is an evolving process of sense-making, characterized by interactions between extracted cues, interpretation and action, context and identity. In the organizational context, one of the main tasks for leaders is interacting with their followers and inspiring followers to achieve great things (Vroom and Jago 2007). During these interactions, supervisors shape their subordinates’ identity, identification and sense of meaning (Sluss and Ashforth 2007; Rosso et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2022). Therefore, we speculate that leaders may shape followers’ calling orientation in the workplace. Buis et al. (2019) also recently pointed out that in view of the prevalence of groups in the workplace, it is surprising to ignore work teams in the theoretical and empirical research of calling orientation. In addition, although calling orientation is characterized by pro-social intention, that is, making the world a better place by enacting specific job roles, it is still unknown whether the “world” includes colleagues. Indeed, literature review by Thompson and Bunderson (2019) pointed out that more studies are needed to examine the behavioral outcomes of calling orientation and answer the question: “Do people with a calling orientation perform more prosocial behaviors?” (Duffy and Dik 2013, p. 433).

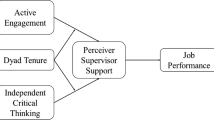

In response to these calls, based on the social impact theory (Kelman 1958), we aim to expand research on calling orientation. Firstly, as a work orientation, calling orientation is susceptible to the social impact of team leaders. The main goal of a team leader’s transformational leadership is to articulate the attractive vision and focus followers’ attention on their contributions to others (Grant 2012). Thus, we propose that a leader’s transformational leadership may contribute to followers’ calling orientation. In addition, in the process of social impact, employees are more likely to accept the influence exerted by leaders with higher organizational status (Yukl 2010). Therefore, we further speculate that when leaders have higher organizational status, leaders’ transformational leadership behavior will be more potential to enhancing followers’ calling orientation. Meanwhile, behavior is a critical output form of an individual after perceiving social information (Kelman 1961). Although prosocial intention, desire to make the world a better place by practicing specific job roles, is an important component of calling orientation, whether the “world” includes colleagues is still unknown. Thus, we introduce followers’ helping behaviors at work as a new behavioral outcome of calling orientation. The research model is depicted by Fig. 1.

The contributions of this study are as follows. Firstly, based on the social impact theory, we empirically examined the managerial antecedent of followers’ calling orientation in teams, and thereby add to the limited stream of research on the contextual predictors of calling orientation. Second, we specify the boundary condition under which transformational leadership can exert effective influence on followers’ work orientation. Power and status are the signs of social impact (Yukl 2010). We enrich previous studies by proposing that the influence of transformational leadership on followers’ calling orientation is moderated by a leader’s organizational status. Thirdly, we extend the work-related outcomes of calling orientation. Although there is a substantial body of evidence demonstrating that viewing the work as a calling is related to a great deal of work-related outcomes, few studies to date have examined how calling is related to overt behaviors (Thompson and Bunderson 2019), especially, whether people with a calling orientation engage in more prosocial behaviors is still unknown (Duffy and Dik 2013).

2 Literature review

2.1 Transformational leadership and calling orientation

Since transformational leadership was proposed, there is a widely shared consensus that transformational leadership is a particularly effective form of leadership in a dynamic and turbulent business environment (Bass and Riggio 2006; Siangchokyoo et al. 2020). Transformational leadership is widely defined as going ‘‘beyond exchanging inducements for desired performance by developing, intellectually stimulating, and inspiring followers to transcend their own self-interests for a higher collective purpose, mission, or vision’’ (Howell and Avolio 1993, p. 891). Transformational leadership involves four types of transformational behaviors: idealized influence; inspirational motivation; intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Idealized influence is the degree to which leaders behave in charismatic ways that make followers identify with them. Inspirational motivation is behavior that leaders articulate visions that are appealing to followers. Intellectual stimulation is behavior that increases followers’ awareness of problems and influences followers to view problems from a new perspective. Individualized consideration is the degree to which leaders respect followers and are concerned with followers’ feelings and needs (Bass and Avolio 1990; Fernando and Colquitt 2006).

Calling orientation includes three basic components: a transcendent summons (that is, feeling an internal or external force to drive oneself to a specific job role), prosocial intention (that is, the desire to make the world a better place by enacting specific job roles), and purposeful work (that is, approaching a particular life role in a manner oriented toward demonstrating or deriving a sense of purpose or meaningfulness) (Dik and Duffy 2009).

Social impact theory points out that people are embedded in the context and easily influenced by the context (Kelman 1958). In the organizational context, leaders are significant others and followers are susceptible to leaders in the team. According to social impact theory, there are at least three reasons that transformational leadership fosters employees’ calling orientation. First, when transformational leaders describe work in ideological terms and focus on the work significance to the life and greater good of the group (Burns 1978; Bass 1985), followers internalize work values and come to connect their personal identity with the work, which will foster their calling orientation. Second, transformational leadership motivates employees to surpass their own interests for the benefit of the team, the organization or the society (Bass 1985), thus helping employees internalize the responsibility of serving the public and improving employees’ prosocial intention in the work. Finally, when transformational leadership provides an attractive vision, the goals can greatly stimulate followers’ recognition mechanism (Jamie et al. 2022) and the meaning of work (Shamir et al. 1993; Stam et al. 2010). Rosso et al. (2010) argued that, when leaders encourage followers to transcend their personal needs or goals, followers come to view their work as more meaningful (Carton 2018). Taken together, we propose Hypothesis 1:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): A leader’s transformational leadership is positively related to followers’ calling orientation.

2.2 The moderating effect of leader’s organizational status

The social impact theory posits that the higher the credibility of information sources, the easier it is to achieve social impact (Kelman 1961). Essentially, leadership is the process whereby intentional influence is exerted over followers by virtue of a leader’s formal and informal power. In this influence process, the greater authority and power the leaders have, the stronger influence will be exerted over followers (Yukl 2010). A leader’s organizational status represents followers’ perception about their supervisor’s authority and power in the organization (Eisenberger et al. 2002). Generally, individuals are more receptive to influences (e.g., role modelling, identification, and compliance) from people with high status in social interaction (Kelman 1958; Yukl 2010; Xu et al. 2021). In the organizational context, leaders who are highly valued and well treated by the organization would be highly identified as organizational agents and would therefore augment the influences of a leader’s leadership behaviours on followers. Thus, when a leader’s organizational status is higher, followers are more receptive to intentional influence exerted by their leader because of instrumental compliance, internalization, and personal identification (Kelman 1958; Yukl 2010). Based on the above argument, we propose Hypothesis 2:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): A leader’s organizational status moderates the relationship between a leader’s transformational leadership and followers’ calling orientation, such that the positive relationship is stronger when a leader’s organizational status is higher.

2.3 Calling orientation and followers’ helping behaviors

Social impact theory further states that when individuals’ attitudes or orientations shaped by social cues, they will output those through behavior and other forms (Kelman 1961). According to social impact theory, we hypothesize that followers’ calling orientation shaped by leaders’ transformational leadership is positively related to their helping behaviors in the workplace. Specifically, the individual having a calling is prosocially oriented or altruistic (Xie et al. 2016); that is, the individual with a calling orientation is other-focused and willing to make personal sacrifices for the welfare of others. Generally, individuals with prosocial or altruistic tendency show more concerns for other peoples’ welfare (Grant 2007; Grant and Mayer 2009; Arthaud-Day et al. 2012) and hence are more likely to engage in helping behaviors. Empirically, there is no study to directly examine the relationship between calling orientation and helping behaviors at work. However, the experimental study conducted by McClintock and Allison (1989) found that individuals with social values were more likely to display helping behaviors, providing the indirect support for the relation between calling orientation and helping behaviors. Taken together, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Followers’ calling orientation is positively related to their helping behaviors at work.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Overview of studies

We conducted two studies to test these hypotheses. In study 1, we used an experimental design to test the casual effects of a leader’s transformational leadership on followers’ calling orientation (Hypothesis 1). In order to replicate the finding of the study 1 and further explore the boundary condition and the effect of followers’ calling orientation on helping behaviors in the workplace, the study 2 performed the cross-lagged survey to test hypotheses 1–3.

3.2 Study 1: an experimental study

3.2.1 Sample, procedure, and measures

We recruited 546 (182 per condition) participants from Chinese universities with inclusion requests that participants must have never participated in similar experiments and possess major backgrounds that have no disturbing effect on the experimental results. We assigned the participants into three conditions (high transformational leadership group, low transformational leadership group and control group). First, participants were presented with the text about a leader encouraging employees to independently research core chips, in which a leader’s transformational leadership was manipulated (see Appendix A) and were then asked to rate leader’s transformational leadership. Next, they were instructed to play a role of chip research with a leader whose transformational leadership was manipulated. After that, they reported their calling orientation. To ensure the quality of experimental data, we set up two questions to test whether the participants are integrated into the situation, including “What is your role” and “What is your job responsibility”. As long as either of the two questions is answered incorrectly, the participants will be excluded. Among the 546 participants who completed the experiment, 71 failed to pass the checks. The final sample consisted of 475 participants (162 in high transformational leadership group, 155 in low transformational leadership group and 158 in control group), leading to a valid response rate of 87%. Among them, 42.53% were female, 50.95% were between 19 and 20 years old. To measure calling orientation, we used the scale from Dik et al. (2012) (e. g., “My work helps me live out my life’s purpose”; 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s α for the scale in three conditions (high transformational leadership group, low transformational leadership group and control group) was 0.93, 0.89, 0.93.

3.2.2 Manipulations check

We selected one item from the four dimensions of Multi-factor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) (Bass and Avolio 1995) to test the effective of the manipulations of transformational leadership. These items are “my leader encourages us to solve problems from different perspectives”, “my leader acts in ways that builds our confidence”, “my leader talks optimistically about the future”, and “my leader considers me as having different needs, abilities and aspirations from others”; 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s α for the scale in high transformational leadership group and low transformational leadership group was 0.81 and 0.87. ANOVA test shows that the manipulations of leader’s transformational leadership (Mhigh transformational leadership = 3.93, Mlow transformational leadership = 2.21, F (1, 316) = 337.84, p < 0.001) were effective in Study 1.

3.2.3 Results

Table 1 shows T-test results of paired samples before and after the test of calling orientation in the experimental group and the control group. As shown in Table 1, participants in different transformational leadership conditions reported different levels of calling orientation. Specifically, participants’ calling orientation improved significantly in high transformational leadership condition (Mpretest = 3.06, SDpretest = 0.76; Mpost-test = 3.52, SDpost-test = 0.86; T (161) = 8.97, p < 0.001), compared with those in low transformational condition (Mpretest = 3.36, SDpretest = 0.71; Mpost-test = 3.18, SDpost-test = 0.76; T (154) = 3.09, p < 0.01) and those in control condition (Mpretest = 2.67, SDpretest = 0.97; Mpost-test = 2.68, SDpost-test = 0.99; T (157) = 0.73, p > 0.05). These results supported Hypothesis 1.

3.3 Study 2: a field survey

3.3.1 Sample and data collection procedure

In order to replicate the finding of study 1 and further explore the boundary conditions and the effects of followers’ calling orientation on helping behaviors at work. We used a survey to replicate hypothesis 1, and tested hypothesis 2 and hypothesis 3.

Participants were recruited from a large state-owned bank in China. With the assistance of the human resources director, employees and supervisors were invited to participate in our survey by an e-mail over the organization’s intranet. The e-mail set out the aims of the study and assured potential participants that their responses would be confidential. Employees and supervisors who were interested in participating could reply via e-mail. In time 1, 1355 questionnaires were distributed to employees from 121 work teams (including a leader’s transformational leadership, a leader’s organizational status and followers’ calling orientation). 1026 responses from employees from 121 teams were obtained, a valid response rate of 75.72%. To reduce common method bias and the burden of leaders (Podsakoff et al. 2003), we randomly chose four subordinates and asked leaders to rate their direct subordinates’ helping behaviors at work. Matching the responses of supervisors to those of their subordinates, we obtained 738 usable questionnaires containing a leader’s transformational leadership, a leader’s organizational status and followers’ calling orientation from 77 work teams, a valid response rate of 54.46%, and 322 usable questionnaires containing followers’ helping behaviors rated by 81 leaders, a valid response rate of 66.94%. In the subordinate sample, 67.28% were female, 84.76% of them received college or above education, the average age was 37.75 years old (SD = 5.70), and the average company tenure was 5.24 years (SD = 4.20). In the leader sample, 50.65% were female, 79.22% of them received college or above education, the average age was 41.81 years old (SD = 6.51), and the average company tenure was 11.25 years (SD = 4.75).

3.3.2 Measures

To reduce common method bias, three techniques were employed. First, a leader’s transformational leadership and organizational status were rated by his or her direct subordinates and aggerated into team levels (Kozlowski and Klein 2000). Second, subordinates’ helping behaviors at work were rated by their direct supervisor. Third, the response instructions of each scale varied. Some were about “agreement” with their perception while others were about the “frequency” with their experience. The average mean score was calculated for the four scales.

A leader’s transformational leadership The transformational leadership questionnaire used in the study (Song et al. 2009) was employed to assess a leader’s transformational leadership behaviors. We adopted shared unit property approach (Chan 1998; Kozlowski and Klein 2000) to collect data, and followers were asked to rate their supervisor’s leadership behaviors on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). A sample item is “my supervisor articulates a compelling vision of the future”. In our sample, the Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.82. The results of aggregation indices of transformational leadership (rwg = 0.94, ICC (1) = 0.20, ICC (2) = 0.94) exceeded conventional standards of agreement (rwg ≥ 0.70, ICC (1) ≥ 0.12, ICC (2) ≥ 0.70) (James 1982), thus supporting aggregation of the transformational leadership measure into a group level construct.

A leader’s organizational status In the Eisenberger et al.’s study (Eisenberger et al. 2002), the unidimensional scale with 12 items was developed to assess supervisor’s organizational status. Consistent with the employees’ judgments, the scale measures supervisor’s informal status in the organization from value, influence and autonomy. In the present study, we selected four high-loading items from Eisenberger et al.’s scale to assess team leader’s informal status in the organization. The items selected were “The organization holds my supervisor in high regard” (value), “The organization gives my supervisor the chance to make important decisions” (influence), “The organization values my supervisor’s contributions” (value), and “The organization gives my supervisor the authority to try new things” (autonomy). Similarly, shared unit property approach (Chan 1998; Kozlowski and Klein 2000) was adopted to collect data of supervisors’ organizational status and followers were asked to rate their supervisor’ status in the organization on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). The aggregation indices of leader’s organizational status (rwg = 0.91, ICC (1) = 0.13, ICC (2) = 0.91) exceeded conventional standards of agreement (James 1982). Taken together, there was support for aggregation of the supervisory status measure into a group level construct. In our sample, the Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.87.

Followers’ calling orientation Consistent with conceptualization of calling, followers’ calling orientation was measured with the 12-item Calling and Vocation Questionnaire with three dimensions, which are each measured with 4 items: transcendent summons (e.g., “I am pursuing my current line of work because I believe I have been called to do so.”), purposeful work (e.g., “My work helps me live out my life’s purpose.”), and prosocial orientation (e.g., “The most important aspect of my career is its role in helping to meet the needs of others.”) (Lee and Allen 2002). Subordinates were given on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true of me) to 6 (totally true of me). In the present study, the Cronbach’s α for calling orientation is 0.90.

Followers’ helping behaviors at work Because organizational citizenship behavior directed to individuals (OCBI) primarily involves helping individuals at work, the OCBI scale developed by Lee and Allen (2002) was used to assess followers’ helping behavior. Direct supervisors were asked to rate subordinates on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = never, 7 = always). A sample item is “Help others who have been absent”, “Give up time to help others who have work or non-work problems”. In our sample, the internal consistency of the scale was 0.93.

Control variables Previous studies have shown that certain socio-demographic variables can affect calling orientation (Wrzesniewski et al. 1997; Duffy and Sedlacek 2007; Dobrow 2013) and helping behaviors (Malek and Tie 2012; Bahrami et al. 2013). Thus, age, organizational tenure, gender (0 = male, 1 = female), and education (0 = associate, 1 = bachelor, 2 = master and above) were considered as potential control variables in the current research.

3.3.3 Preliminary analysis

To justify that multilevel analyses were appropriate to analyze the nested data of this study, we next examined the between-group variance in followers’ calling orientation. Specifically, the null model with no predictors and followers’ calling orientation as the dependent variable was examined. The result showed that between-group variance in followers’ calling orientation was significant (τ00 = 0.03, p < 0.01), indicating that there was group effect and multilevel analyses were appropriate (Chen et al. 2012).

Second, as recommended by Bernerth et al. (2018), we analyzed whether it was necessary to control for four socio-demographic variables. By removing control variables uncorrelated with dependent variables, it is possible to avoid potential spurious effects that controls may have when they are significantly related to the predictor, but not the criterion variables (Kraimer et al. 2011; Xie et al. 2017). The results showed that only followers’ organizational tenure predicted their calling orientation, therefore we controlled followers’ organizational tenure when testing the hypotheses.

3.3.4 Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 2 showed the means, standard deviations and correlations among the study variables at level one and level two.

3.3.5 Hypothesis testing

Hypothesis 1 stated that a leader’s transformational leadership is positively related to followers’ calling orientation. Model 1 in Table 3 shows that a leader’s transformational leadership was positively related to followers’ calling orientation (B = 0.47, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

Hypothesis 2 stated that a leader’s organizational status moderated the relationship between a leader’s transformational leadership and followers’ calling orientation. Model 2 in Table 3 shows that a leader’s organizational status moderated the relationship between that leader’s transformational leadership and followers’ calling orientation (B = 0.28, SE = 0.06, p < 0.01). Figure 2 also shows the relationship between a leader’s transformational leadership and followers’ calling orientation is more pronounced when a leader’s organizational status is higher. Simple slope tests indicated that, when a leader’s organizational status is high, the relationship between that leader’s transformational leadership and followers’ calling orientation was significant (B = 0.54, p < 0.001; 95% CI = [0.52, 0.56]); when a leader’s organizational status is low, the relationship between transformational leadership and followers’ calling orientation was significant (B = 0.42, p < 0.001; 95% CI = [0.40, 0.44]). However, the slope difference between high and low levels was 0.14 and was significant with 95% CI = [0.08, 0.15]. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

Hypothesis 3 states that followers’ calling orientation is positively related to their helping behaviors at work. Model 3 in Table 3 shows that a followers’ calling orientation was positively related to their helping behaviors, rated by their direct supervisor (B = 0.27, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

4 General discussion

The main aim of this study was to investigate the leadership antecedent and behavioral outcomes of calling orientation. Based on the social impact theory, we used an experimental design and a questionnaire survey to examine the relationship between a leader’s transformational leadership, followers’ calling orientation and followers’ helping behaviors at work. Multilevel analyses showed that a leader’s transformational leadership has potential to encourage their followers’ calling orientation. A leader’s organizational status played a moderating role in the relationship between a leader’s transformational leadership and followers’ calling orientation. In addition, regression analysis illustrated that followers’ calling orientation was positively related to their helping behaviors at work, rated by their direct supervisor. This study contributes to calling and transformational leadership literature and provides important practical implications for team leaders and organizations.

4.1 Theoretical implications

This study extends existing knowledge and provides theoretical implications in three ways. First, this study further supports the posterior hypothesis of the formation of calling, and expands the antecedents of calling orientation. In view of the positive role of calling, scholars have called for more research on the antecedents of calling (Duffy and Dik 2013; Lysova et al. 2019). Recently, some scholars have begun to explore the individual predictors (Creed et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2018). However, people still know little about the contextual predictors of calling, especially the human factors in the work team (such as leaders, colleagues, etc.) (Buis et al. 2019). Based on the social impact theory, this study investigated the contextual predictors of followers’ calling orientation in the work team and found that a leader’s transformational leadership behavior significantly predicted followers’ calling orientation, enriching and expanding the antecedents of calling.

Second, this study extends the work-related outcomes of calling orientation by examining the effect of followers’ calling orientation on their helping behaviors at work. Although the past two decades have witnessed a great deal of scholarly attention to examining the effects of calling orientation on individuals’ career or work-related outcomes, few studies to date have examined how calling is related to overt behaviors. Indeed, Duffy and Dik’s literature review stated that more studies are needed to examine the behavioral outcomes of calling, especially, they called for researchers to examine the question: “Do people with a calling perform more prosocial behaviors?” (Duffy and Dik 2013, p. 433). Drawing on the social impact theory, the present study found that followers’ calling orientation was positively related to their helping behaviors at work.

Third, the present study contributes to the transformational leadership literature. Transformational leadership is defined as going ‘‘beyond exchanging inducements for desired performance by developing, intellectually stimulating, and inspiring followers to transcend their own self-interests for a higher collective purpose, mission, or vision’’ (Howell and Avolio 1993, p. 891). However, few studies have tested this potential hypothesis. Experimental study and survey showed that transformational leadership inspired employees to surpass their own interests and be willing to contribute to a larger collective goal by practicing specific job roles.

4.2 Practical implications

The pursuit of meaningful, purposeful work has been encouraged by industry, business leaders, and popular writing. The tenet of encouraging a view of work as a calling is that calling orientation provides employees with a deep sense of meaning and is related with to positive work-related outcomes (Jin et al. 2022). This study provides practical enlightenment for organizations to cultivate and develop followers’ calling orientation and helping behaviors at work. To begin with, our study revealed that a team leader’s transformational leadership behavior was positively related to their followers’ calling orientation. This finding suggests that, to facilitate followers’ calling orientation, managers should engage in more transformational leadership behaviors, such as behaving in charismatic ways, articulating attractive visions, increasing follower awareness of problems, and influencing them to view problems from a new perspective. Second, our results showed that, when a leader’s organizational status is high, the effect of a leader’s transformational leadership on followers’ calling orientation was more pronounced than when supervisory status was low. Generally, transformational leadership is believed to be a particularly effective leadership style in the dynamic and turbulent business environment in that they lead subordinates to effectively deal with the uncertainties in the external environment (Bass and Riggio 2006; Van Knippenberg and Sitkin 2013; Wang et al. 2017). The findings emphasize the necessity of developing transformational leadership style for leaders in high organizational status (especially senior leaders) from a new perspective of cultivating employees’ calling orientation. Third, as an important aspect of organizational citizenship behavior, helping behavior is highly recognized. It is worth paying attention to strengthening interpersonal relationships with other members of the organization. Employees should lend a helping hand to their colleagues when they need it, and work hand in hand, thus improving the possibility of gaining reputation and praise in social interaction and promoting their career success.

4.3 Limitations and future directions

Our research has several limitations that suggest avenues for further research. First, although data for this study was collected from multiple sources to reduce the concern with common method bias, this study was cross-sectional in nature. Therefore, we cannot draw causal inferences from our results, although the links examined in this study followed a presumed causal order. Indeed, there may be alternative explanations for our findings. For example, Duffy et al. (2013) argued that people with a calling may perform more prosocial behaviors, but it is possible that specific behavioral steps are performed to maintain or enhance their sense of calling. Accordingly, rather than calling orientation evoking helping behavior, it is possible that helping behavior evokes sense of a calling. Consequently, a longitudinal research design is needed to replicate our results. Second, in order to eliminate the potential confounding effects of exogenous variables, such as industry characteristics and organizational culture, we recruited our sample from a single organization. Although this practice can increase the internal validity of research, it reduces the external validity of the results (Kantowitz et al. 2014). Therefore, more research is needed to determine whether our findings can generalize to other organizational contexts in China and be replicated in other cultural contexts.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arthaud-Day, M.L., J.C. Rode, and W.H. Turnley. 2012. Direct and contextual effects of individual values on organizational citizenship behavior in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology 97 (4): 792–807. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027352.

Bahrami, M.A., R. Montazeralfaraj, H.S. Gazar, and A.D. Tafti. 2013. Demographic determinants of organizational citizenship behavior among hospital employees. Journal of Dairy Research 5 (4): 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022029912000271.

Bass, B.M. 1985. Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B.M., and B.J. Avolio. 1990. The multifactor leadership questionnaire. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Bass, B.M., and B.J. Avolio. 1995. Manual for the Multifactor leadership questionnaire: Rater form (5X short). Palo Alto: Mind Garden.

Bass, B.M., and R.E. Riggio. 2006. Transformational Leadership, 2nd ed. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Bernerth, J.B., M.S. Cole, E.C. Taylor, and H.J. Walker. 2018. Control variables in leadership research: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Management 44 (1): 131–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317690586.

Buis, B.C., A.J. Ferguson, and J.P. Briscoe. 2019. Finding the “I” in “Team”: The role of groups in an individual’s pursuit of calling. Journal of Vocational Behavior 114: 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.02.009.

Burns, J.M. 1978. Leadership. New York: Harper and Row.

Carton, A.M. 2018. “I’m not mopping the floors, I’m putting a man on the moon”: How NASA leaders enhanced the meaningfulness of work by changing the meaning of work. Administrative Science Quarterly 63 (2): 323–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839217713748.

Chan, D. 1998. Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. Journal of Applied Psychology 83 (2): 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.234.

Chen, X., J.L. Farth, and A.S. Tsui. 2012. Empirical methods in organization and management study. Beijing: Peking University Press.

Chen, L., T. Wen, J. Wang, and H. Gao. 2022. The impact of spiritual leadership on employee’s work engagement–a study based on the mediating effect of goal self-concordance and self-efficacy. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 24 (1): 69–84. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2022.018932.

Creed, P.A., S. Kjoelaas, and M. Hood. 2016. Testing a goal-orientation model of antecedents to career calling. Journal of Career Development 43: 398–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845315603822.

Dalla Rosa, A., M. Vianello, and P. Anselmi. 2019. Longitudinal predictors of the development of a calling: New evidence for the a posteriori hypothesis. Journal of Vocational Behavior 114: 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.02.007.

Dik, B.J., and R.D. Duffy. 2009. Calling and vocation at work: Definitions and prospects for research and practice. The Counseling Psychologist 37 (3): 424–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000008316430.

Dik, B.J., and A.B. Shimizu. 2019. Multiple meanings of calling: Next steps for studying an evolving construct. Journal of Career Assessment 27 (2): 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072717748676.

Dik, B.J., B.M. Eldridge, M.F. Steger, and R.D. Duffy. 2012. Development and validation of the calling and vocation questionnaire (CVQ) and brief calling scale (BCS). Journal of Career Assessment 20 (3): 242–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711434410.

Dobrow, S.R. 2013. Dynamics of calling: A longitudinal study of musicians. Journal of Organizational Behavior 34 (4): 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1808.

Duffy, R.D., and B.J. Dik. 2013. Research on calling: What have we learned and where are we going? Journal of Vocational Behavior 83: 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.06.006.

Duffy, R.D., and W.E. Sedlacek. 2007. The presence of and search for a calling: Connections to career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior 70: 590–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.03.007.

Eisenberger, R., F. Stinglhamber, C. Vandenberghe, I.L. Sucharski, and L. Rhoades. 2002. Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology 87 (3): 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.3.565.

Fernando, R.F., and J.A. Colquitt. 2006. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal 49 (2): 327–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159766.

Grant, A.M. 2007. Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Academy of Management Review 32 (2): 393–417. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24351328.

Grant, A.M. 2012. Leading with meaning: Beneficiary contact, prosocial impact, and the performance effects of transformational leadership. Academy of Management Journal 55 (2): 458–476. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0588.

Grant, A.M., and D.M. Mayer. 2009. Good soldiers and good actors: Prosocial and impression management motives as interactive predictors of affiliative citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology 94 (4): 900–912. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013770.

Howell, B.M., and B.J. Avolio. 1993. Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, locus of control, and support for innovation: Key predictors of consolidated-business-unit performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 78 (6): 891–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.6.891.

Huang, J.L., R. Cropanzano, A. Li, P. Shao, X.A. Zhang, and Y. Li. 2017. Employee conscientiousness, agreeableness, and supervisor justice rule compliance: A three-study investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology 102 (11): 1564–1589. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000248.

James, L.R. 1982. Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology 67 (2): 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.67.2.219.

Jamie, P., H. Sarah, and C. Grant. 2022. “Goals give you hope”: An exploration of goal setting in young people experiencing mental health challenges. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 24 (5): 771–781. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2022.020090.

Jin, W., J. Miao, and Y. Zhan. 2022. Be called and be healthier: How does calling influence employees’ anxiety and depression in the workplace? International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 24 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.32604/IJMHP.2022.018624.

Kantowitz, B., H. Roediger, and D. Elmes. 2014. Experimental Psychology. Stamford: Cengage Learning.

Kelman, F.C. 1958. Compliance, identification, and internalization: Three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution 2 (1): 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200275800200106.

Kelman, H.C. 1961. Processes of opinion change. Public Opinion Quarterly 25: 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1086/266996.

Kozlowski, S.W.J., and K.J. Klein. 2000. A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual, temporal, and emergent processes. In Multilevel theory, research and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions, ed. K.J. Klein and S.W.J. Kozlowski. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kraimer, M.L., S.E. Seibert, S.J. Wayne, R.C. Liden, and J. Bravo. 2011. Antecedents and outcomes of organizational support for development: The critical role of career opportunities. Journal of Applied Psychology 96 (3): 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021452.

Lee, K., and N.J. Allen. 2002. Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology 87 (1): 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.131.

Lysova, E.I., B.J. Dik, R.D. Duffy, S.N. Khapova, and M.B. Arthur. 2019. Calling and careers: New insights and future directions. Journal of Vocational Behavior 114: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.03.004.

Malek, N.A., and F.H. Tie. 2012. Relationship between demographic variables and organizational citizenship behavior among community college lecturers. Advances in Educational Administration 13: 117–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3660(2012)0000013010.

McClintock, C.G., and S.T. Allison. 1989. Social value orientation and helping behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 19: 353–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1989.tb00060.x.

Podsakoff, P.M., S.B. MacKenzie, J.Y. Lee, and N.P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5): 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Rosso, B.D., K.H. Dekas, and A. Wrzesniewski. 2010. On the Meaning of Work: A Theoretical Integration and Review. Research in Organizational Behavior 30: 91–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001.

Shamir, B., R.J. House, and M.B. Arthur. 1993. The Motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organization Science 4 (4): 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.4.4.577.

Siangchokyoo, N., R.L. Klinger, and E.D. Campion. 2020. Follower transformation as the linchpin of transformational leadership theory: a systematic review and future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly 31 (1): 101341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101341.

Sluss, D.M., and B.E. Ashforth. 2007. Relational identity and identification: Defining ourselves through work relationships. Academy of Management Review 32 (1): 9–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.23463672.

Song, L.J., A.S. Tsui, and K.S. Law. 2009. Unpacking employee responses to organizational exchange mechanisms: The role of social and economic exchange perceptions. Journal of Management 35 (1): 56–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308321544.

Stam, D., D.V. Knippenberg, and B. Wisse. 2010. Focusing on followers: The role of regulatory focus and possible selves in visionary leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 21 (3): 457–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.009.

Sturges, J., M. Clinton, N. Conway, and A. Budjanovcanin. 2019. I know where I’m going: Sensemaking and the emergence of calling. Journal of Vocational Behavior 114: 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.02.006.

Thompson, J.A., and J.S. Bunderson. 2019. Research on work as a calling…and how to make it matter. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 6 (1): 421–443. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015140.

Van Knippenberg, D., and S.B. Sitkin. 2013. A critical assessment of charismatic—transformational leadership research: Back to the drawing board? Academy of Management Annals 7 (1): 1–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2013.759433.

Vroom, V.H., and A.G. Jago. 2007. The role of the situation in leadership. American Psychologist 62 (1): 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.1.17.

Wang, H.J., E. Demerouti, and P.L. Blanc. 2017. Transformational leadership, adaptability, and job crafting: The moderating role of organizational identification. Journal of Vocational Behavior 100: 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.03.009.

Wrzesniewski, A., C. McCauley, P. Rozin, and B. Schwartz. 1997. Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality 31 (1): 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2162.

Xie, B., M. Xia, X. Xin, and W. Zhou. 2016. Linking calling to work engagement and subjective career success: The perspective of career construction theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior 94: 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.02.011.

Xie, B., W. Zhou, J.L. Huang, and M. Xia. 2017. Using goal facilitation theory to explain the relationships between calling and organization-directed citizenship behavior and job satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior 100: 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.03.001.

Xu, J., B. Xie, Y. Yang, and L. Li. 2021. Voice more and be happier: How employee voice influences psychological well-being in the workplace. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 23 (1): 41–53. https://doi.org/10.32604/IJMHP.2021.013518.

Yukl, G. 2010. Leadership in Organizations, 7th ed. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Zhang, C., A. Hirschi, B.J. Dik, J. Wei, and X. You. 2018. Reciprocal relation between authenticity and calling among Chinese university students: A latent change score approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior 107: 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.05.005.

Zhu, Y., T. Chen, J. Wang, M. Wang, R.E. Johnson, and Y. Jin. 2020. How critical activities within COVID-19 intensive care units increase nurses’ daily occupational calling. Journal of Applied Psychology 106 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000853.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China under Project 72272117.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: this study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (project no. 72272117).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. BX, XZ and JM distributed with the work done in the project. BX searched the background materials, designed the analytical characterization and empirical study frame. XZ analyzed the concepts and perfected the framework. JM analyzed the data and evaluated the results. All authors have contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committees of Wuhan University of Technology. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A

Appendix A

1.1 Manipulation materials in study 1

1.1.1 Manipulation materials of leader’s transformational leadership

High transformational leadership condition Imagine you have been working for an integrated circuit production company. You are responsible for developing high-performance processor chips. Before this April, your company has been working with a company from other countries, which provided your company with components for producing electronic products. However, in April, the foreign company announced that it would no longer sell electronic components to your company in the next seven years, which posed a great challenge to your company. In order to enhance the core competitiveness, your company decided to develop a competitiveness chip belonging to your company. As the senior manager in charge of chip research and development in your department, your leader Liu Wei was appointed by the company to lead the chip research and development project.

Facing the fierce high-tech competition, Liu Wei first held a meeting to remind us that it is the biggest hidden danger that the core technology is subject to others. Only by self-reliance can you be invincible. He encouraged you to attack “core” to overcome difficulties, strengthen basic research and development, be brave in innovation and master more key technologies with independent intellectual property rights. In daily work, he took the initiative to interact with you, asking you about various problems and difficulties encountered in R&D, and actively looking for solutions. In order to make everyone get new development opportunities, he built a core research team, and set up innovative team awards and individual awards. He always encouraged you that chip research and development will not be accomplished in a short time. He encouraged that the team will break through the blockade, and make greater contributions to the development of the industry.

Low transformational leadership condition Imagine you have been working for an integrated circuit production company. You are responsible for developing high-performance processor chips. Before this April, your company has been working with a company from other countries, which provided your company with components for producing electronic products. However, in April, the foreign company announced that it would no longer sell electronic components to your company in the next seven years, which posed a great challenge to your company. In order to enhance the core competitiveness, your company decided to develop a competitiveness chip belonging to your company. As the senior manager in charge of chip research and development in your department, your leader Liu Wei was appointed by the company to lead the chip research and development project.

Faced with the fierce and complicated high-tech competition, Liu Wei first held a meeting to convey that the company was ready to research and develop chips independently, but he didn’t emphasize the importance of this task. He just told you that you don’t have too much pressure and you can continue to stick to your posts normally. In daily work, he hardly took the initiative to carry out any private interaction with you, and he was completely indifferent to all kinds of problems and difficulties you encountered in R&D. He didn’t provide you with any development opportunities and platforms for the new project, and he didn’t promise any rewards to the team or individuals. He has always emphasized that if you want to stay in the company, you must work overtime and make more efforts, otherwise you will be resigned.

Control group condition Please read the following passage: During the ice age, people crossed 1500 km and migrated from the vast land mass connecting Siberia and northern Canada. With the end of the ice age, this piece of land called “Bering Land Bridge” became the Bering Strait. However, the “land bridge theory” has gradually lost its popularity, and there are some signs that humans may have sailed to America along the Pacific coast. Archaeological discovery of 14,000-year-old human settlements in America is enough to prove that early people went upstream from the sea mouth and stepped inland, such as Paisley Cave on the Pacific coast of Oregon. Now, there is more definite evidence that humans did not arrive in America by the Bering Land Bridge.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baoguo, X., Xiaowen, Z. & Jialing, M. The managerial antecedent and behavioral consequence of subordinates’ calling orientation: an experimental and survey study. MSE 2, 4 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44176-023-00014-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44176-023-00014-7