Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) has proven to be a valuable tool for education. It might perform different functions to facilitate teaching and learning experiences, with a learning companion being one of them. However, teachers often have little understanding of the pool of opportunities provided by AI-powered tools. Having a learning companion in a language classroom is crucial. However, getting involved in human–computer interaction requires understanding of the services that the machine can offer, whether it is a text written as a response to students’ input, feedback provided to help students gauge their language level or translation prompt helping students understand the reading text. This research aims at displaying the range of AI services that are applicable in the foreign language classroom and grouping them according to their functionality. The authors selected 150 available in open access online instruments that apply AI and evaluated them against the criteria, which allowed them to organize these tools into categories according to their possible applications in the classroom. This might help teachers make informed decisions about the appropriate tool for certain teaching situations or recommend to their students a tool that could enhance the learning experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has penetrated all areas of our lives, including education, which has provoked a boom in AI-related research. Systematic literature reviews recently conducted by Zawacki-Richter et al. [39], Bozkurt et al. [7], Liang et al. [27], Chen et al. [12] and Chiu et al. [13] indicate that, at a conservative estimate, studies on AI in education (AIEd) have tripled compared to the previous decade. Such interest is quite legitimate and could be explained by the fact that it is imperative for educators to integrate AI tools into classrooms to keep up with the technological advancements. Keeping the curriculum relevant to current technological trends ensures that education remains effective and meaningful. All the stated requirements are equally applied to teachers of specific subjects including English language instructors.

Nevertheless, educators are not blindly optimistic about the potentials AI tools may provide. The expanding pool of theoretical data and empirical research results provoked a heated debate on the merits and demerits of introducing AIEd for in-class teaching and out-of-class interaction. For example, Luckin and Holmes [28] claim that AIEd could offer needed support at different stages including the time before a learner begins formal education (p. 42). Holmes and Tuomi [20] believe that rapid increase of AIEd systems could even stimulate new pedagogical approaches (p. 544). Zhang et al. [40] argue, however, that despite the fact that modern intelligent tutoring systems are already as good as human tutors, educators and parents should be aware of potential harm of such AI-driven tools. Having analysed research papers and educators’ responses Oshchepkova et al. [31] discovered that overall attitude to technologies in education and specifically AI assisted instruments has become cautious due to such negative side effects as potential cognitive overload, dehumanisation of the learning process, and privacy concerns. Several researchers including Cotton et al. [15] are concerned that AI tools might actually undermine the purpose of education. Wang and Wang [37] alert educators about the emerging AI learning anxiety.

Nevertheless, these negative effects and caution could be mitigated through professional development opportunities related to AI. With many educational reforms and standards now emphasising the integration of digital technologies, including AI tools, into teaching, it is essential for educators to adapt to these requirements. Such professional development ensures that educators are better equipped to integrate AI tools effectively and responsibly, thereby avoiding potential pitfalls.

One of the difficulties related to application of AIEd is the range and diversity of emerging tools. As an advanced AI tool, ChatGPT has become a buzzword among educators. An impressive number of research articles have been written on various aspects of ChatGPT application in which the possibilities and threats that this tool presents are discussed. However, other AI instruments should not be ignored, as they might also contribute to the learning process.

AI has become an intelligent learning companion, tutor and moderator. In this article, we analyse the different roles such tools may play to assist the learner. Undoubtedly, it is impossible to list all the AIEd applications that can be used in the language classroom, taking into consideration their growing variety. We are attempting to equip teachers with a comprehensive mechanism that will help them find a suitable tool for a particular teaching context. This will, in turn, ease the burden of planning the course material instead of imposing more stress on a teacher trying to disentangle the web of technically enhanced opportunities.

Given the fact that there are no commonly agreed definitions of AI, we should set boundaries regarding what constitutes an AI tool in the context of this study and serves as the basis for the suggested classification. In this paper, we focus on AI-driven tools in language education. These are digital resources or software leveraging artificial intelligence to enhance material design for a language classroom and to support learning by processing natural language and identifying data patterns.

Therefore, this study aims to address the current gap in providing a comprehensive practice-oriented overview of the existing and emerging AI tools with the focus on the instruments applicable for teaching English as a foreign language. Since it is not feasible, nor particularly helpful to describe each application separately, the authors have made an attempt to find the basis for grouping the known tools into categories, which might help specialists make informed decisions about the appropriate tool for certain teaching situations.

The main sections of the article are literature review that provides an overview of existing typologies of AIEd tools, methodology where the authors describe the principles of selecting and classifying the AI-tools for the current research, the suggested categorization with detailed explanations and specific examples of each subcategory. After that, the authors provide practical recommendations on how the proposed classification might be used by a practicing English language teacher and draw conclusions about further possible research topics.

2 Literature review

As mentioned earlier, research publications related to AI have grown exponentially in recent years. Nevertheless, this field of knowledge remains unexplored. An observation made by Alam [1] can partially justify the existing discrepancy: ‘Most developmental researches are concentrated on AI technologies instead on its applicable or practical aspects, the spread of AI into new application fields—such as education—is slower than the technology’s (AI) growth’ (p. 1). In other words, educators are not yet capable of catching up with rapidly emerging technologies and adapting them to their teaching objectives.

The literature review revealed that there are still fewer studies on AI use in education than in other areas, such as healthcare [26, 29, 34], business [6], journalism [8] or sports management [23].

One can find publications related to the application of AIEd in general [11, 12, 16, 25], but, as was noticed by Dogan et al. [19], AIEd studies are often purely technical and ‘ignore issues such as pedagogy, curriculum, and instructional/learning design’ (p. 10). Since the majority of AI services were initially developed without the intention of being used for teaching purposes, it will take time and effort to find their proper place in the learning process.

Little has been achieved in exploring how AI tools can be adapted to teaching specific subjects. Zawacki-Richter et al. [39] showed that the majority of academic papers on AI and higher education were from computer science and STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics).

There have also been attempts to explore how AI tools may benefit English language teaching. For instance, Kannan and Munday [22], Sharadgah and Sa’di [35] and Huang et al. [21] list the potential merits of applying AI in language teaching, such as tailoring the teaching materials according to learners’ needs and language level, responding to students’ questions, interacting with learners in a human-like manner and allaying learners’ anxieties. Quite often, though, research is narrowed down to an application of a specific tool, such as the online essay evaluation service Criterion [9], chatbot Replika [24], intelligent personal assistant Alexa [18], lexical database WordNet [36] and chatbot ChatGPT [5, 30].

Despite all the research efforts, AIEd remains a very vague concept. As a result, practicing teachers might have little understanding of it as something unknown and unpredictable and refrain from systematically using it in the classroom.

As we have observed, there is no uniformity in the terminology used to label various AIEd tools. Researchers have identified different groups of AI tools according to their purposes. Some of the groups were formed as the result of the analysis of previously written research papers [16, 27, 38, 39], while others were the categories suggested by the authors [3, 10]. Table 1 lists some examples of AIEd tool classifications presented in academic publications.

To sum up the information presented in Table 1, the most often identified roles of AI technologies are profiling and predicting educational results, followed by intelligent tutoring systems and assessment and evaluation. One of the problems related to these groups and classes is that it is difficult to draw a clear demarcation line and refer some AI tools to a specific category. For instance, there might be very little difference between ITSs and adaptive systems. Another drawback of this categorisation is that it is quite general and does not help a practicing teacher understand and select appropriate tools. Similar problems occur when we analyse the classification of AI tools related to a specific subject. Table 2 presents some examples of AI tools identified by foreign language teaching specialists.

Several authors [38, 41] differentiate AI tools used for ELT according to the target language skill areas that they help to develop (speaking, listening, writing, pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary and reading).

Subject-related classification might be more helpful, as it provides a wider range of ideas for practical applications of the illustrated tools. Nevertheless, these publications lack pragmatic element which we intend to integrate into our research.

Overall, literature review confirmed our anticipation that the existing pool of publications on AIEd is vast yet quite confusing for educators because these research papers often provide patchwork vision of the available AI-driven tools. Besides, most of them concern the education process in general without any reference to a specific subject, which gives teachers little understanding of how these tools can be used and how they can impact various aspects of the learning process.

Therefore, we attempted to develop a more detailed practice-oriented and down-to-earth taxonomy of AI tools applicable in an ELT classroom and provide practicing teachers with some guidelines.

3 Method

As seen in the literature review, the research field of AIEd has undergone a tremendous transformation, which has had a profound impact on teaching and learning. While ChatGPT commands considerable attention, we consider it imperative not to lose sight of the broader array of AI-powered tools that might benefit the process of language teaching. As the instruments currently lack comprehensive characterisation, we aim to tentatively provide a systematic classification based on the criteria, which will be described in the following section.

The authors possess qualification and expertise in digital technologies and AI-powered tools application, language teaching, and educational technology, which were used to analyse the practical usefulness of each instrument in various teaching scenarios.

This research falls under the category of qualitative analysis, as the authors conducted content analysis to identify patterns. In total, 150 online instruments that apply AI and are available in open access were reviewed. Criteria listed in Table 3 were applied for AI tools selection purposes.

Having in mind to conduct a broader analysis of existing AI-powered tools, we opted to exclude such criteria as compatibility and integration capability. We did not consider it necessary for tools to be compatible with multiple devices as most of them are available as browser versions and theoretically can be used across devices. We also excluded capability of AI tools to integrate with other educational technologies, such as LMSs. Some AI tools, particularly those designed for content development, function independently. Including these criteria could have narrowed the array of tools available for our analysis, potentially excluding valuable instruments.

The initial step of the analysis entailed a data collection process based on the criteria stated in Table 3. The authors compiled a list of AI tools that could potentially enhance language teaching through instructional support or creation of educational materials. To ensure the accessibility of the analysed tools, only those ones that are freely accessed or offer a free trial period were included. Recognising that not all language educators have advanced digital competence, we selected tools that were particularly user-friendly.

We compiled an extensive database which contained the following information: the name of the AI-powered tool, its URL, and its functions such as text-to-text, text-to-audio, text-to-image. These labels later facilitated the development of our classification system. The next step was to apply, analyse, and categorise the collected data according to the predetermined criteria for the analysis stated in Table 4.

Identifying the type of media each tool supports, including audio, video, text and animation, was essential for understanding the capabilities of the tools and potential applications in language instruction. This involved practical testing and reviewing the documentation of the tool. We also gathered insights on the tools usability by reviewing forums, online platforms, and communities of practice where these tools were discussed.

Next, we collected examples of how each tool could be used for educational purposes, even if such uses were not initially anticipated by the developers. This was achieved by brainstorming and experimenting with each AI tool. We identified ways they could be utilized in language instruction, devising hypothetical educational scenarios and cases, and then testing the tools to validate the ideas. For example, text-to-image tools were utilized for creating visual aids, illustrating vocabulary, designing infographics to support language instruction. Text-to-audio tools were employed for converting written text into speech for listening exercises and audio storytelling.

Having reviewed the instruments from these perspectives, including media types, current application, potential educational uses, and specific application in ELT, we classified them into groups and categories aiming to create a practical guide for language teachers which might enable them to select AI tools for material design and other teaching situations. Our structured approach ensures that educators can make informed decisions to effectively integrate these technologies in their classrooms.

4 Classification of AI-powered tools

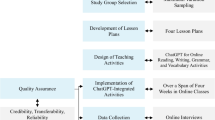

Based on the analysis of all the AI-powered tools at our disposal and their brief descriptions, we devised a classification which might help English language teachers vary their teaching process and assist learners in a more efficient language acquisition. Given that language teaching is closely connected to linguistics, one might assume that most services should focus on text-to-text capabilities. However, language teaching also involves understanding of teaching approaches and methodologies, cognitive processes related to language acquisition, memory, and learning. Consequently, the creation of instructional materials often extends beyond language analysis, incorporating visual and audio elements. Considering these two factors, we established two main categories for our classification: general purpose AI tools adaptable to various media production needs (particularly for designing ELT instructional materials) and professional tools with specialised functionalities to cater to a specific domain. Further scrutiny of the professional category revealed tools that are used for other domains such as programming, solving mathematical problems, statistics, etc. This led to creation of a subcategory for AI tools specifically designed for language and language instruction in particular. The classification is visually represented in Fig. 1 and is explained and exemplified hereafter.

4.1 General-purpose AI tools

Within the context of our research, we encountered a significant number of tools that can be referred to as general-purpose AI tools. Although primarily used in media production and not originally intended for educational purposes, these tools can be effectively repurposed for developing ELT instructional materials, for instance, to produce high-quality listening comprehension exercises, to develop instructional videos or visual aids. This category falls into the subsequent groups, each corresponding to the key media types: audio, video and graphics.

Delving deeper, the audio production group can be further subdivided into two subgroups: (1) sound generation tools, through which AI systems autonomously create musical compositions and sounds of various genres and for diverse needs, and (2) text-to-speech production tools, which focus on the transformation of any written test into spoken language, providing a spectrum of attributes such as inter alia timbral variations, age- and gender-specific distinctions, accents and more.

Despite the fact that these apps were initially designed for purposes other than education, they might find their way into classrooms. When considering the practical application of audio subgroups to ELT, several ideas emerge. Thus, within the sound generation subgroup, AI tools prove to be particularly valuable when the necessity of creating introductions for educational language podcasts and vidcasts or crafting background instrumental music arises. To exemplify such royalty-free services, we may name just a few: Beatoven ai or Soundraw.

On the other hand, the subgroup of AI tools specialising in the transformation of text into speech offers a valuable resource for educators, especially those who teach languages and seek to create their own listening materials. This is particularly relevant when the need arises to have additional listening tasks that focus on specific vocabulary or to create text types that may not be available in standard teaching materials. Access to a great diversity of voices can facilitate the development of a wide range of customised tasks tailored to the needs of individual students. This subgroup may be exemplified by such AI tools as Murf, Natural Reader, Voicemaker, PlayHT, ElevenLabs. To demonstrate the practicality of these AI-powered tools, we conducted a survey to evaluate whether the generated recordings could be used to create EFL listening exercises. Ninety participants were provided with six recordings: one was a studio recording of a human voice, and the other five were generated using the AI services listed. Participants were asked to identify which recording represents a human voice. Surprisingly, only 21 participants identified the correct recording, while the rest of the votes were scattered among the AI-generated recordings. ElevenLabs was the most convincing, receiving 39 votes for its likeness to natural human pronunciation. These findings suggest that such a tool could provide ELT educators with an inexhaustible source of diverse recordings.

The video group incorporates AI tools designed for video and animation production. While developing and delivering an educational course, there are situations in which it becomes essential for students not only to hear the speaker but also to visually connect with the content. There might also be cases when it is imperative to foster a sense of the educator’s presence within the online platform. Moreover, there may arise the necessity of creating educational videos or animations that present complex concepts in a simplified way or portray situational dialogues, enabling students to witness these scenarios enacted by animated characters. It is not always feasible to record such a video for several reasons. First, the production costs associated with video recording of a brief two- to three-minute segment are high. Moreover, the prospect of appearing on camera might be intimidating for certain educators. In addition, other logistical or financial constraints might arise that impede access to professional video production studios. In such scenarios, the services capable of generating videos or animations become invaluable, as they assist educators in creating good-quality teaching materials tailored for their context. This subgroup may be exemplified by such AI tools as Hugging Face, GenMo, Synthesia, HeyGen, and Pictory.

It is also worth highlighting some services that are capable of animating 2D images. Even though this type of animation may not have a direct connection to language teaching activities, it does offer the potential to introduce additional layers of satisfaction to the educational experience, particularly for educators catering to young learners. Among the services in this group, a notable example includes Animated Drawings.

Finally, the graphics group includes tools designed for both image generation and comic production. In Fig. 1, the image generation tools labelled as ‘text-to-image’ can be employed to create illustrative or demonstrative aids for texts, idioms, riddles etc. Such tools can be turned into students’ learning companions by making them ‘co-authors’. For instance, after writing a text, students might request a graphics generator to create an image that aligns with the written passage. For this purpose, such a tool with an established reputation as the widely recognised Midjourney can be considered, as well as lesser-known services such as Deep AI, Leonardo ai, Recraft ai, and Ideogram ai.

The second subgroup of the graphics-generating tools stands out for their capacity to create an extensive range of comics that might serve as fundamental components for teaching dialogue. Among the services encompassed within this spectrum, the one worth mentioning is Hugging Face: Comic Factory.

4.2 Language teaching AI tools

As we have illustrated above, educators, and language teachers in particular, have discovered ways to apply general-purpose AI tools for their instructional needs and material design. However, there is another group of tools that was labelled in Fig. 1 as ‘professional AI tools’. These applications are tailored for various professional purposes. Since our primary interest lies within the realm of ELT, we analysed AI-powered instruments that are purpose-built for the field of language teaching. These tools, which can be considered both learning companions for students and teaching assistant for educators, support various aspects of the ESL educational process. This category can be further subdivided into four principal groups, each serving a distinct function: content creation tools, which aid in the development of educational text materials; assessment tools, which facilitate the evaluation of student written and oral performance; tutoring tools, which provide personalised instruction and support; and planning tools, which help educators organize and structure their teaching strategies and lesson plans.

Within the subgroup of content creation tools, we identified two fundamental subcategories: text generation tools and machine translation. Text generation tools are multifaceted instruments that enable language educators to create a wide range of customised, text-based learning materials, including essays, articles, dialogues and exercises, which meet specific criteria, such as educational goals, difficulty levels, vocabulary, and subject matter. As a result, educators are provided with a varied and relevant collection of content for in-class practice. These tools are also equipped with a set of features that streamline the rapid generation of instructional materials, such as study guides, assessment materials including discussion questions, multiple-choice questions, true or false statements and much more, all accomplished within a matter of seconds. We may exemplify such services by naming AI tools, such as Twee and Cohesive.

Machine translation tools play a central role in overcoming language barriers and facilitating the seamless conversion of content from one language to another, which greatly broadens access to a diverse array of linguistic resources. While machine translation services are primarily utilised by students, it is imperative for educators to have a comprehensive understanding of how these services function. Equally crucial is their ability to enlighten students about the intricacies, potential pitfalls and consequences of relying on machine translation tools, particularly in the context of language learning. Two of the most commonly employed machine translation services by students are Google Translate, DeepL, and Machine Translation with the latter steadily gaining popularity. This AI-powered tool enhances the translation process by evaluating, comparing, and analysing outputs from nine different machine translation engines, including DeepL, Amazon, Google, Libre, and Groq. The system grades the translations and offers details on the differences in term translations across various engines, enhancing the overall translation accuracy and understanding.

The group of AI-powered assessment tools encompasses a collection of instruments, which we divided into the following four distinct subgroups: vocabulary analysis tools, general text analysis tools, grammar checkers, and oral speech analysis.

Vocabulary analysis tools are specifically designed to assess and enhance learners’ vocabulary. These tools conduct a comprehensive analysis of written works based on various metrics. For instance, they gauge learners’ language proficiency by defining the level of the words used. They also pinpoint weak verbs that create vague or unclear contexts, detect words unsuitable for written texts, and identify noun clusters and long noun phrases. In addition, they provide statistical data about grammar structures, such as passive voice and modals, used by the student. These metrics are essential for evaluating the quality of written assignments and delivering precise feedback to students. The diversity within vocabulary analysis tools is vast, and we can exemplify it by mentioning a couple, such as Road to Grammar: Text Analyzer and Expresso.

The subgroup of text structure analysis AI-powered tools specialises in the analysis of written texts with a focus on their structural attributes, cohesion or the detection of plagiarism. The latter is included in the subgroup as the main method of plagiarism detection involves searching for exact word-for-word matches to identify identical or similar phrases and sequences of words. This comprehensive evaluation aids in improving text-based assessment practices. To provide students with valuable feedback, educators must possess a profound mastery of the language, scrupulous attention to detail and a high level of expertise. Additionally, detecting plagiarism is essential as it ensures academic integrity. All of this can be time-consuming, particularly when educators aim to cater to the individualised strengths and weaknesses of each student, resulting in an increased workload. However, the progression of AI has paved the way for the development of multiple services, with the potential to substantially improve assessment and evaluation procedures in language education. To illustrate such platforms, we refer to Smodin and ProWritingAid.

The subgroup of grammar checkers provides support by identifying and correcting grammatical errors, thereby contributing to enhanced language accuracy. When discussing grammar checkers, it is reasonable to mention several notable options for consideration, for example, Grammarly, Virtual Writing Tutor and QuillBot.

Within the subgroup of oral speech analysis tools, the instruments are designed to thoroughly evaluate and refine learners’ pronunciation, speech patterns, and fluency, with a focus on fostering the development of effective oral communication skills. These tools leverage phonetic technologies to provide accurate assessment. Examples of tools within this subgroup encompass AI Pronunciation Trainer, Cathoven pronunciation assessment API, Speechace, and Speech Analyzer which are known for their speech recognition features and functionalities.

The group of AI-powered tutoring tools provides a comprehensive range of resources that cater to the needs of both language learners and educators. Within this group, it is possible to differentiate between such specific subgroups as language learning platforms and chatbots.

Language learning platforms are designed to provide users with immersive and comprehensive language learning experiences. They offer a vast diversity of exercises and interactive components. These platforms leverage the potential of AI to improve users’ language skills by systematic assessment of their experience and creation of exercises that cater to the individual needs of each student, whether it is grammar, vocabulary or conversational skills. Leading examples in this subgroup include Duolingo and Rosetta Stone.

The subgroup of chatbots comprises AI-driven conversational agents that engage with learners in human-like dialogues, offering personalised language practice and instant feedback. It is worth noting, though, that current AI-powered chatbots predominantly generate written responses, which are read aloud by text-to-speech tools but do not offer direct pronunciation of the responses without written support texts. Nevertheless, it is a temporal challenge in this domain that will be solved within a short period of time. ZenoChat and TalkPal can be used as illustrations of the services within this subgroup.

The planning tools group includes instruments specifically designed to assist educators in creating detailed course designs, lesson plans, and learning objectives. These tools focus on tailoring content to the target audience, course level, learning needs, and instructional model. Notable examples of such tools include Learnt.ai, Teachology.ai, and Magic School ai.

Our systematic classification of AI tools provides a well-structured framework for understanding and organising these tools based on their primary functions and applicability within language teaching. This framework enables educators to navigate the rich landscape of AI-powered tools, facilitating informed decisions in selecting tools that align with their pedagogical objectives.

Although we have systematically categorised AI-powered tools into distinct groups, there might be instances when educators encounter integrated platforms that encompass multiple functionalities.

5 Discussion

Having conducted a comprehensive analysis and categorisation of AI tools suitable for language educators in the task of creating instructional materials, facilitating classroom interaction and out-of-classroom practice, we realised that AI-powered tools can perform multiple functions. Since one of the points for discussion among educators is that AI is becoming a learners’ companion, we tried to illustrate the different roles that AI tools may perform. Thus, the AI tool may become a language learner’s companion by performing several identified functions, for example, by providing feedback on the vocabulary or grammar structures used, generating a picture based on the learner’s input, responding to a learner’s questions, or translating an excerpt into a target language. Immediate responses might be a source of motivation as well as an indicator of the areas in which the students need to improve their efforts.

Although teachers cannot have full control of how students apply AI services, we believe that this process should be monitored and facilitated. The students are usually more aware than their teachers of the variety of tools; however, they often either misuse them, which might result in plagiarism, or do not have enough expertise in selecting and applying these tools to enhance language learning. Therefore, teacher–learner collaboration is as important as ever in this respect.

We have outlined a conceivable procedure for choosing AI-powered tools that align with specific teaching requirements and objectives. Initially, educators should determine areas of language instruction that require AI tool development. These may encompass, but are not limited to, vocabulary enrichment, grammar or pronunciation assessment or conversational skills. Simultaneously, the teacher should identify the pedagogical objectives intended for the utilisation of AI tools. The provided classification framework can then be employed to select AI tools in accordance with the outlined teaching objectives. In certain scenarios, it may be advantageous to adopt a combination of AI-driven tools to address diverse instructional needs. Before using the tool in class, it is important to make sure the learners are aware of its functionality and can apply it independently or with support from their peers or teachers.

Hereafter, a possible scenario of the selection process is illustrated. An educator intends to design a listening comprehension exercise. In this scenario, the initial step involves selecting a text generative tool to create a suitable text for the listening activity. It may be necessary to generate several passages to enable the educator to select one that aligns best with the instructional needs and requirements. Following the refinement of the narrative, the educator should consider employing a text assessment tool to ensure that it matches the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) standards suitable for the students’ proficiency level. Afterwards, it might be useful to utilise a generative AI tool to create multiple-choice questions that will help check the comprehension of the text. Finally, to provide students with an audio component, a general-purpose audio text-to-speech tool can be employed to convert the text into an audio format for listening.

We believe that the suggested approach considerably extends previous research on AI as it provides a practice-oriented procedure of selecting a suitable tool for a foreign language classroom. English language teaching specialist are offered a taxonomy of instruments that they can use to identify the suitable tool for a specific teaching situation and to categories the preferred tools that they might already be using.

6 Conclusion

Artificial intelligence services have started penetrating all spheres of our lives and have proved to be helpful in education. Despite the fact that these tools were not intended for teaching purposes and might be seen by educators as potentially threatening due to issues related to ethics and privacy, they have found their way into classrooms, and multiple benefits of this penetration have been identified. Numerous research papers reveal the obvious merits of these tools and provide lists of available applications. Still, more practical advice might be beneficial for teachers to encourage them to experiment with AI technologies in their courses.

The recent trend of AIEd is to provide ‘adaptive, personalised and individualised learning environments, which could help provide greater access to higher education for learners and reduce the burden on teachers’ [14] (p. 35). However, educational theories are not frequently discussed in research on AIEd; therefore, practicing teachers remain not involved, as they are not equipped with a clear vision of how these magic tools might be applied in their subject-specific teaching context and how human–computer interaction might enhance their learner’s experience.

As literature review revealed, most of the suggested AIEd tools descriptions are quite general and not subject-specific. In our research, we have provided a classification of available AI-powered tools and services from the point of view of their practical application in the language learning classroom. Language educators have the freedom to select from general-purpose AI tools and adapt them to the needs of language learners or utilise language teaching AI tools that were specifically designed for ELT. This classification is practice-based and easy to use, which might contribute to the change in the status of AI, which remains underdeveloped and often ignored in education [25].

The following important comments should be made about the pedagogical appropriateness of the selected AI tools:

-

1.

It is essential to acknowledge the supplementary role of AI tools, which are intended to enhance the teaching process rather than serve as substitutes for educators.

-

2.

Thorough and precise task descriptions for AI tools are critical because the level of detailing ensures a more satisfactory outcome.

-

3.

When creating text-based instructional materials, thorough review and analysis are essential. Even with clear objectives, AI tools may occasionally generate content that does not align with the intended purpose.

-

4.

Key ethical principles should be followed to prevent misuse of private data, perpetuation of bias and stereotypes, or occurrence of any form of discrimination.

One of the limitations of the present research is that some of the tools might have been overlooked; however, our overall aim was not to provide a complete list of possible tools but rather to suggest a path practicing teachers may use to ‘feel the taste’ of applying AI in teaching. Another possible trap that any attempt at classification falls into is that some apps fit more than one category. In this case, it is not realistic to draw a distinct line between the groups; therefore, a more scrutinised study of the available and emerging services is required. Although our research focuses on the examination of the tools designed to enhance the experience of language teaching and learning, it might be useful for a wider community of educators, as they might rely on the same principles of analysis and investigate similar services that are applicable in their disciplines and allow humans to expand their abilities via man–machine symbiosis.

Overall, application of AIEd reveals multiple opportunities for educators that do not only enhance the way learners master the subject, but also allow teachers to broaden their competences and professional skills. We believe this research is a significant contribution on the way to a more profound understanding of AI, its strengths and limitations in the domain of English language teaching and education in general as it provides a comprehensive representation of the major categories of AI-driven tools, which might help educators make an informed decision about the instruments that are most suitable for their teaching context.

Further research of the topic is required to evaluate the effectiveness of the listed tools, to discover and illustrate new functions these instruments might perform, and to expand the listed classification considering new emerging technologies. Therefore, we appeal to policymakers, educational stakeholders, and other parties involved to consider integrating AI tools based on the guidelines provided in this paper.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Alam A. Possibilities and apprehensions in the landscape of artificial intelligence in education. In: 2021 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Applications (ICCICA) (pp. 1–8). 2021. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCICA52458.2021.9697272.

Al Braiki B, Harous S, Zaki N, Alnajjar F. Artificial intelligence in education and assessment methods. Bull Electr Eng Inf. 2020;9(5):1998–2007. https://doi.org/10.11591/eei.v9i5.1984.

Al-haimi B, Hujainah F, Nasir D, Alhroob E. Higher education institutions with artificial intelligence: roles, promises, and requirements. In: Hamdan A, Hassanien AE, Khamis R, Alareeni B, Razzaque A, Awwad B, editors. Applications of artificial intelligence in business, education and healthcare. Springer; 2021. p. 221–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72080-3_13.

Baker T, Smith LS. Educ-AI-tion Rebooted? Exploring the future of artificial intelligence in schools and colleges. Nesta. 2019.

Bin-Hady WRA, Al-Kadi A, Hazaea A, Ali JKM. Exploring the dimensions of ChatGPT in English language learning: a global perspective. Library Hi Tech. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-05-2023-0200.

Borges AF, Laurindo FJ, Spinola MM, Goncalves RF, Mattos CA. The strategic use of artificial intelligence in the digital era: systematic literature review and future research directions. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;57:102225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102225.

Bozkurt A, Karadeniz A, Baneres D, Guerrero-Roldán AE, Rodríguez ME. Artificial intelligence and reflections from educational landscape: a review of AI Studies in half a century. Sustainability. 2021;13(2):800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020800.

Broussard M, Diakopoulos N, Guzman AL, Abebe R, Dupagne M, Chuan C-H. Artificial intelligence and journalism. J Mass Commun Quarter. 2019;96(3):673–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699019859901.

Burstein J, Chodorow M, Leacock C. Automated essay evaluation: the criterion online writing service. AI Mag. 2004;25(3):27–27. https://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v25i3.1774.

Celik I, Dindar M, Muukkonen H, Järvelä S. The promises and challenges of artificial intelligence for teachers: a systematic review of research. TechTrends. 2022;66(4):616–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-022-00715-y.

Chassignol M, Khoroshavin A, Klimova A, Bilyatdinova A. Artificial intelligence trends in education: a narrative overview. Proc Comput Sci. 2018;136:16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.08.233.

Chen X, Zou D, Xie H, Cheng G, Liu C. Two decades of artificial intelligence in education. Educ Technol Soc. 2022;25(1):28–47. https://doi.org/10.30191/ETS.202201_25(1).0003.

Chiu TK, Xia Q, Zhou X, Chai CS, Cheng M. Systematic literature review on opportunities, challenges, and future research recommendations of artificial intelligence in education. Comput Educ Artif Intell. 2023;4: 100118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100118.

Chu HC, Hwang GH, Tu YF, Yang KH. Roles and research trends of artificial intelligence in higher education: a systematic review of the top 50 most-cited articles. Austral J Educ Technol. 2022;38(3):22–42. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.7526.

Cotton DRE, Cotton PA, Shipway JR. Chatting and cheating: ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innov Educ Teach Int. 2024;61(2):228–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2190148.

Crompton H, Burke D. Artificial intelligence in higher education: the state of the field. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2023;20:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00392-8.

De la Vall RRF, Araya FG. Exploring the benefits and challenges of AI-language learning tools. Int J Soc Sci Human Invent. 2023;10(1):7569–76. https://doi.org/10.18535/ijsshi/v10i01.02.

Dizon G, Tang D. A pilot study of Alexa for autonomous second language learning. In: Meunier F, Van de Vyver J, Bradley L, Thouësny S, editors. CALL and complexity—short papers from EUROCALL 2019. pp. 107–112. Research-publishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2019.38.994

Dogan ME, Goru Dogan T, Bozkurt A. The use of artificial intelligence (AI) in online learning and distance education processes: a systematic review of empirical studies. Appl Sci. 2023;13(5):3056. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13053056.

Holmes W, Tuomi I. State of the art and practice in AI in education. Eur J Educ. 2022;57(4):542–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12533.

Huang X, Zou D, Cheng G, Chen X, Xie H. Trends, research issues and applications of artificial intelligence in language education. Educ Technol Soc. 2023;26(1):112–31. https://doi.org/10.30191/ETS.202301_26(1).0009.

Kannan J, Munday P. New trends in second language learning and teaching through the lens of ICT, networked learning, and artificial intelligence. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación. 2018;76:13–30. https://doi.org/10.5209/CLAC.62495.

Keiper MC, Fried G, Lupinek J, Nordstrom H. Artificial intelligence in sport management education: playing the AI game with ChatGPT. J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ. 2023;33: 100456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2023.100456.

Kim NY. A study on the use of Artificial Intelligence Chatbots for improving English grammar skills. J Dig Convergen. 2019;17(8):37–46. https://doi.org/10.14400/JDC.2019.17.8.037.

Lameras P, Arnab S. Power to the teachers: an exploratory review on artificial intelligence in education. Information. 2022;13(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13010014.

Lee H. The rise of ChatGPT: exploring its potential in medical education. Anat Sci Educ. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.2270.

Liang JC, Hwang GJ, Chen MRA, Darmawansah D. Roles and research foci of artificial intelligence in language education: an integrated bibliographic analysis and systematic review approach. Interact Learn Environ. 2021;29:1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1958348.

Luckin R, Holmes W. Intelligence unleashed: an argument for AI in education. London: Pearson; 2016.

Moons P, Van Bulck L. ChatGPT: can artificial intelligence language models be of value for cardiovascular nurses and allied health professionals. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2023;22:55–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvad022.

Mondal H, Marndi G, Behera JK, Mondal S. ChatGPT for teachers: practical examples for utilizing artificial intelligence for educational purposes. Indian J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2023. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijves.ijves_37_23.

Oshchepkova T, Tolstykh OM, Panasenko EV, Nazarova NA, Petrova NV. Examining changes in foreign language educators’ attitudes towards the use of computer-assisted learning. Stud Engl Lang Educ. 2024;11(2):630–49. https://doi.org/10.24815/siele.v11i2.36441.

Papaspyridis A, La Greca J. AI and education: will the promise be fulfilled? In: Araya D, Marber P, editors. Augmented education in the global age. Routledge; 2023. p. 119–36.

Pokrivcakova S. Preparing teachers for the application of AI-powered technologies in foreign language education. J Lang Cult Educ. 2019;7(3):135–53. https://doi.org/10.2478/jolace-2019-0025.

Rong G, Mendez A, Assi EB, Zhao B, Sawan M. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: review and prediction case studies. Engineering. 2020;6(3):291–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2019.08.015.

Sharadgah TA, Sa’di RA. A systematic review of research on the use of Artificial Intelligence in English language teaching and learning (2015–2021): What are the current effects? J Inf Technol Educ Res. 2022;21:337–77. https://doi.org/10.28945/4999.

Vij S, Tayal D, Jain A. A machine learning approach for automated evaluation of short answers using text similarity based on WordNet graphs. Wireless Pers Commun. 2020;111:1271–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-019-06913-x.

Wang YY, Wang YS. Development and validation of an artificial intelligence anxiety scale: an initial application in predicting motivated learning behavior. Interact Learn Environ. 2019;30(4):619–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1674887.

Woo JH, Choi H. Systematic review for AI-based language learning tools. J Digital Contents Soc. 2021;22(11):1783–92. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2111.04455.

Zawacki-Richter O, Marín VI, Bond M, Gouverneur F. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education—where are the educators? Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2019;16(1):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0.

Zhang L, Hu X, Andrasik F, Feng S. Benefits and potential issues for intelligent tutoring systems and pedagogical agents. In: Hampton AJ, DeFalco JA, editors. The frontlines of artificial intelligence ethics. Routledge; 2022. p. 84–101.

Zou B, Liviero S, Hao M, Wei C. Artificial intelligence technology for EAP speaking skills: student perceptions of opportunities and challenges. In: Freiermuth MR, Zarrinabadi N, editors. Technology and the psychology of second language learners and users. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2020. p. 433–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34212-8_17.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Olesya M. Tolstykh suggested the research idea, developed methodology for the research, was responsible for the final approval of the version to be submitted and published. Tamara Oshchepkova completed the literature review, drafted the paper, and verified the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tolstykh, O. ., Oshchepkova, T. Beyond ChatGPT: roles that artificial intelligence tools can play in an English language classroom. Discov Artif Intell 4, 60 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-024-00158-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-024-00158-9