Abstract

The Industrial landscape in Italy is characterized by small medium enterprises. The information technology sector is teaming with a broad spectrum of players from smaller ones up to large system integrators that have access to the most advanced technologies. The present paper aims at analysing the recently published Italian AI Strategy framing it within the context of the Italian IT industry. It references to data gathered in a small scale survey on AI adoption of Italian IT companies, and provides an analysis of the Italian AI Strategies focusing on the risks that its implementation will have to face and eventually draws three different scenarios on AI adoption in the Italian productive system. The Italian industrial landscape witnessing a growing adoption of AI-enabled solutions, mostly driven by cost efficiency consideration. There are, however, the first indication of leveraging AI to increase the offer portfolio, generating more revenues. New technologies supporting AI in the small, embedded AI and distributed AI come handy in leveraging those data. A concurrent push of the Italian Government to foster AI and to promote standardization and sharing of data (GAIA-X initiative—Italian Regional Hub) will provide further steam to the increased adoption of AI. The paper is structured in the following sections: “Introduction”, “Trends in AI adoption in the industrial context”, “An AI Policy for Italy: commenting on the Italian AI Strategy”, “Future Scenarios” providing a pessimistic, realistic and optimistic views, “Conclusions”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper aims at assessing the Italian AI Strategy within the context of the Italian industrial sector. In Part 2 it provides some insights on AI adoption within the Italian IT industry and references some other research which focused on the Italian private sector AI market. Overall, the Italian Industrial landscape is characterized by few large companies and a broad set of small and medium enterprises with limited innovation adoption [1]. As a matter of fact, the Government and the largest industrial actors are aware of the competitive edge that AI adoption can provide. However, given the abundance of companies with a short term business horizon—like SMEs—the real challenge is to pursue a multi-year transformation program.

In this setting, the Italian Government, has defined an AI Strategy—discussed in Part 3—that highlights the challenges, cultural landscape, insufficient availability of talents/skill, limited adoption of AI by public administrations, reliance on foreign platforms and proposes a plan to address them in the context of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan. Many of the policy proposals are noteworthy however I believe the Strategy implementation will face some risks due to its unclear governance, funding and political instability. I believe that external pressure (EU) and internal push (Trade Associations) will be key factors to fulfil the objectives stated in the Strategy.

Given the context described in the second section and the policies analysed in the third one I propose some possible future scenarios. I outline an “optimistic” scenario, a “intermediate/realistic” one and a “pessimistic view”, this latter accounts for the possibility that funding and political focus is derailed from AI to other contingent issues.

All in all, I remain confident, as pointed out in the conclusion, that the adoption of AI by industry is inevitable and will be steered by the international advances in this area both in terms of platforms and supra-national AI infrastructures (synthetic data).

The technology evolution of AI that is pointing towards simpler ways of using it and embedding it into companies processes and products, along with the support provided by trade associations (e.g. Anitec-Assinform, Confindustria Digitale) will play a crucial role in fostering AI adoption. Additionally, it can be envisaged that Italian system integrators could have a key role in socializing the “practical” use of AI and could be a driving force in AI adoption in the coming years.

2 Trends in AI adoption in the industrial context

The Italian industrial landscape is characterized by a few big, national and transactional companies and a multitude of small medium enterprises, both addressing a national and global marketplace.

A significant number of industries are operating in well-established market with low-medium innovation level (like textile, leather, furniture, construction, food-chain, packaging, etc.). These companies are more focused, in terms of innovation, on the processes than on product innovation (pending few notable exceptions) [19]. For these companies, AI arrives “pre-packaged” in the tools that they are acquiring to support manufacturing and manufacturing processes (including supply and delivery chain).

Big companies have adopted AI in many steps of their life cycle, most of the time to increase their processes effectiveness. The application covers all life cycle phases, from product design up to product monitoring and upgrade.

A new, important, evolution in the uptake and application of AI is deriving from the accelerated Digital Transformation of industries and of the supply/delivery chain.

This transformation creates more and more data and the need to manage them. It is a short step to the exploitation of those data and here is where AI comes to play.

It is also the most challenging—at this time—application since most small and medium enterprises lack the skill for data management and also lack the foresight of understanding how to leverage data.

Along these lines the European GAIA-X initiative, supported by the Italian Government is fostering the creation of data spaces and companies are becoming aware of the importance to organize their data according to the emerging de-facto standards based on GAIA-X guidelines. Significant results are already available in the automotive sector (steered by Germany and France) and results in the healthcare, agriculture and tourism are expected soon.

New technologies, like GAN—Generative Adversarial Networks-, make it possible to leverage on relatively limited data set, extracting meaning, trends and more generally intelligence.

In turns, this opens up the possibility to further increase efficiency, as an example by introducing more effective pro-active maintenance cycles, as well as creating new services.

Another area of interest for AI application that is already well entrenched (and rapidly evolving) is the one of customers relation, with the adoption of chatbots that are now being refined to be tailored on each specific customer (the chatbot recognizes the returning customer and is aware of previous interactions). This is becoming really close to the generation of Personal Digital Twins to assist and support customers.

2.1 Insights on AI adoption in the IT industry from: evidence from a small-scale survey

The Anitec Assinform, the Italian Association of Information and Communications Industry, has set up a working group on AI that has published two White Papers [2, 3], in 2021 and 2022, aiming at outlining the state of the art of AI adoption in the Italian industrial landscape and proposing actions to further it.

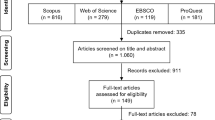

The most recent White Paper focused on AI solutions adopted by Italian ICT companies [4]. The work gathers data from a small survey submitted to companies in September–October 2021. 22 companies took part; hence the data cannot be considered statistically representative. Nevertheless, the key findings are consistent with larger scale studies and provide some useful insights.

It appears that AI adoption still does not have a relevant impact on revenues but has a consistent and beneficial impact on cost. Italian IT companies appear to be using AI solutions mostly for Security, Production and Supply Chain Management, whereas Human Resources resulted being the least AI intensive area. For what concerns software used to develop AI, 81% of the sample uses either Cloud or Software as a Service (ClaaS and SaaS), 72% adopts in-house solutions, 50% open source solutions. On premises and Off-the-Shelf solutions appear to be less common. As the questionnaire involved ICT companies these results are not surprising. 86% of the respondents declared that their AI budget will increase in the next 3 years whereas it will stay the same for the remaining 14%. Italian ICT companies clearly are sensing the growing importance and the potential of AI solutions in business.

Lastly, the study addresses the main issues hampering the adoption and development of AI solutions within a company. 14 out of 22 respondents pointed out insufficient data quality as a main obstacle to AI development, 13 out of 22 raised the issue of data unavailability, whereas 9 out 22 declared that the inability to find adequate skills on the labour market hampers their capability to adopt AI and develop AI solutions. Moving from IT industry surveys to research concerning the whole private sector, I see that the main obstacles to AI adoption for Italian companies are still the excessive costs of technology and the insufficient amount of public funding [1].

3 An AI policy for Italy: commenting on the Italian AI strategy

On November 24th 2021 the Italian Government adopted its AI Strategy [5] (Programma Strategico nazionale per l’intelligenza Artificiale). It should be noted that this is not the first Italian AI Strategy, as a previous Plan was published in 2020 (with a draft version already published in 2019) [5]. In fact, most of the analysis and the scientific literature currently available refer to the first Italian AI Strategy rather than the second [6, 7]. This paragraph aims to critically assess the latest Italian AI Strategy. Our analysis is divided in three parts. In the first one, I sketch the socio-political context in which the Strategy has been published, in the second I summarize its content and in the last section I provide a general assessment and address some of the risks that its implementation could face. My impression is that—in a context of political instability—there has been too little effort on the governance (monitoring the execution and providing feedback for fine tuning) of the Strategy; thus, the external pressure from the EU and the internal push from trade associations will be a key enabler for the strategy’s success.

3.1 Context

According to the OECD AI Policy Observatory, 60 countries and territories (plus the EU) all over the world have published at least one AI policy Initiative [8]. Among those also stands Italy. In fact, the Italian Government published two multi-sectorial policy plans, the first one in 2020 and a more recent one in 2021. The 2020 plan was officially published by the Ministry of Economic Development during the Conte II Cabinet, whereas the 2021 plan was jointly released by the recently-born Ministry of Technologic Innovation and Digital Transition, the Ministry of Economic Development and the Ministry of University and Research during the Draghi Cabinet.

An encompassing assessment on why there has been the need of publishing two different AI Strategies in such a short timeframe would go beyond the scope of this paper. However, drawing a few possible explanations could be useful for understanding the implementation risks that new National AI Strategy is facing. A first possible cause of the failure of the 2019 National Strategy is political instability. Italy has a long story of short-lived governments, and it is possible that the Draghi cabinet did not want to implement an AI strategy that was developed by a different government. However, it is much more likely that the new Government wanted to adapt the AI Policy Planning to the new public policy context.

The AI Policy scenario changed dramatically in 2021 with two key developments: at the supranational level the publication of the EU’s AI ACT, at the national level the publication of the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan. The former is the first attempt to build a horizontal regulation of Artificial Intelligence, the latter is the EU’s largest recovery plan with massive resources allocated to digitalization. The new Strategy’s success relies on the implementation of the AI ACT and, even more, of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, as it is strongly linked to both these policy initiatives.

Lastly, I should address as a contextual element the Gaia-X initiative. Data is a fundamental part in the creation and operation of artificial intelligence applications. The emergence of new AI algorithms like GAN—Generative Adversarial Networks- that can operate on smaller subset of data streams and the parallel availability of transformers, like GPT-3, GLaM, and of synthetic data opens up the AI game, and applicability, to a variety of SMEs. The data availability remains crucial, and in particular the availability of usable data. This is what has prompted the EU to support the GAIA-X initiative and in turns moved several enterprises to join the initiative and a few Governments, among these the Italian one, to support the creation of GAIA-X national hubs with the goal to develop data spaces. The Italian Government has indicated as priority for national data spaces the ones on: circular economy, fashion, health & wellbeing, tourism and culture, manufacturing, mobility. Therefore, it is clear that this initiative on data space will be another key enabler for AI adoption in the Italian productive system.

3.2 Assessing the Italian strategic program on Artificial Intelligence

The Italian AI Strategy [5], officially named Programma Strategico Nazionale Intelligenza Artificiale 2022–2024 (Strategic Program on Artificial Intelligence) is a relatively short document, consisting in 35 pages and divided in four main chapters. As mentioned, the Strategy has been developed by three Ministries (Economic Development, University and Research, Digital Transition and Technological Innovation) and written by a small working group of experts (Gruppo di lavoro sulla Strategia Nazionale per l’Intelligenza Artificiale). Interestingly, the working group that worked on this Strategy is much smaller than the one that worked on the 2019 one. It is also remarkable that the working group is composed only by experts coming from the Academia: 8 of the 9 members of the WG are Computer Science Professors. The 2021 Strategy contains no notice of any direct involvement from Industry representatives or scholars coming from fields such as Economics, Sociology, Ethics etc.

The first chapter of the Strategy document analyses the context in which it was adopted, namely the Italian AI ecosystem:

-

The features of the Italian AI Ecosystem, focusing on research communities, knowledge transfer centres, technology and solution providers, private and public user organisations.

-

A synthetic yet effective comparison between the Italian AI Ecosystem and its international peers (Germany, UK and France).

The Strategy’s assessment of the Italian AI ecosystem shows that the Italian AI Scientific Community has good research quality and output, although it suffers from issues of scale in research labs, poor talent attraction, dramatic under-representation of women and limited patent capacity. It is also remarkable that the Italian private AI market reached in 2020 an overall value of €300 million with a 15% growth over previous year [9] (more recent data range between € 327 million [10] and €380 million [11]), around 3% of the EU private AI market (whereas the Italian GDP accounts for 12% of the EU GDP). When compared to the other main European countries, the main gaps concern R&D spending, patenting and AI applications. The first chapter outlines in its conclusion the four main strategies [12] that Italy will have to face [13]:

-

1.

Strengthen its AI research base and funding

-

2.

Foster measures to retain and attract talent

-

3.

Improve its technology transfer process

-

4.

Increase AI adoption among firms and public administration as well as foster the creation of innovative enterprises.

The second chapter discusses the anchoring, the guiding principles and the goals of the Strategy. The Italian AI Strategy is explicitly anchored to the EU strategy on Artificial Intelligence [14]. In fact, the Strategy responds the 2018 European Commission Coordinated Plan on AI (COM(2018)795) “encouragement” to develop national AI strategies. The Italian AI plan also references the AI ACT and its proposal of a European Artificial Intelligence Board. Italy does not seek an alternative ecosystem of trust [15] and seems to be fully aligned with the EU design.

The EU-Italy alignment re-emerges in three of the five Guiding Principles of the Italian Strategy. The first “guiding principle” states plainly: “Italy’s AI is a European AI (L’IA Italiana è un’IA europea)”. The third one—“Italy’s AI will be human-centred, trustworthy and sustainable” (L’Intelligenza artificiale italiana sarà antropocentrica, affidabile e sostenibile)—echoes the Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI developed by the European Commission’s High Level Expert Group on AI [20]. The fifth one reflects the European Commission approach on AI in public services “Govern AI and govern with AI”, whilst the remaining two statements regarding research and business do not have such an explicit EU referencing. Despite acknowledging—in the first chapter—the relatively small size of the Italian AI research community, the ambition outlined in the strategy is high: “Italy will be a global research and innovation hub of AI”. The same goes for business: “Italian companies will become leaders of AI-based research, development and innovation”. In this respect, the Italian AI strategy rhetoric reflects a narrative that emphasises leadership intervention in the context of a global AI race, which has been addressed in the scientific literature on AI National Strategies [16].

Lastly, the second chapter lists the Strategy “objectives” and priority sectors. The formers are clearly linked with the weaknesses of the AI Ecosystems as outlined in the “context” chapter:

-

1.

Advance frontier research in AI

-

2.

Reduce AI research fragmentation

-

3.

Develop and adopt human-centred and trustworthy AI

-

4.

Increase AI-based innovation and the development of AI technology

-

5.

Develop AI-driven policies and services in the public sector

-

6.

Create, retain and attract AI talent in Italy.

The priority sectors (Manufacturing, Education system, Agri-food, Culture and tourism, Health and wellbeing, Environment, infrastructures and networks, Banking and Finance, Public Administration, Smart cities, National Security, Information Technologies) include industries where Italy has a competitive advantage (e.g. manufacturing, agri-food and health) and strategic industries (e.g. national security, IT).

The third chapter represents the core of the Italian AI Strategy. Here the objectives and the guiding principles boil down to 24 policy recommendations divided into three “Strategic Areas of Intervention”: “Talent and Skills”, “Research”, “Applications”. The “Talent and skills” area only includes policies aiming to develop human resources with AI skills, while the “Research” area is split between policies concerning fundamental AI research and Challenge-driven AI research. Lastly, the “Applications” area includes policies addressing AI adoption in the Private sector and in Public Services.

Out of 24 policy proposals, 5 concern the “Talent and Skills” area, 8 the “Research” area and 11 the “Applications” area (among the latter, 5 are targeted to the private sector and 6 to the public sector). I will not review each policy proposal, but rather try to provide a general assessment.

The “Talent and skills” area focuses on developing AI Skills for human resources that are entering the labour market (PhD programs, vocational/technical education, research grants, promotion of STEM courses and careers). There are no policy provisions for professional and continuous training. It is also noteworthy that, despite Italy has a poor DESI score [17], the Strategy does not include any plan on digital literacy/AI literacy among the general population.

The policies in the “Research” area aim to connect the already existing research centres, helping the Italian scientific AI community to scale-up and produce close to market solutions. In this light, the idea of launching an Italian AI Research Data and Software Platform seems particularly interesting, as it could potentially be a key enabler for the interaction between research centres, start-ups and companies within the ecosystem.

The “Applications” area measures are divided into two subgroups: AI for modernizing enterprises and AI for modernizing Public Administration. The former addresses the issues of hiring high-skilled personnel in private companies, the adoption of AI solutions, start-ups scaling up and the certification of AI products (a subject closely linked to the EU’s AI ACT proposal). D.3, D.4 and D.5 policy proposals are clearly referencing the AI ACT, as they regard sandboxes, AI systems’ conformity assessments, and SMEs’ targeted information campaigns (articles 52, 43 and 53). The policy proposals targeting public administrations and public services are also quite noteworthy. Other than “strengthening AI solutions in the Public Administration and GovTech ecosystem” (E.2), there are a few measures that directly address data-related issues:

-

Creating integrated datasets for Open Data and Open AI Models (E.3)

-

Creating a common Italian language resource dataset for AI development (E.4)

-

Creating datasets and AI/NLP based analytics for feedback and service improvement in PA (E.5)

-

Creating datasets and AI/Computer Vision based analytics for service improvement in PA (E.6)

These are probably the most imaginative and ambitious policy provisions bestowed by the Strategy. If implemented, the Strategy will enable data exploitation via the creation of tools which can be extremely useful for both businesses and public services. However, it should be noted that—unlike all the other policy proposals in the Strategy—none of the proposals for AI in the public administration have a potential funding source, therefore it can be assumed that their implementation will be less likely.

The final chapter of the Strategy deals with its governance. It is an extremely short section (consisting of only eight lines). It states that the Ministry of Technologic Innovation and Digital Transition, the Ministry of Economic Development and the Ministry of University and Research will establish an AI permanent Working Group to monitor the implementation of the Strategy. The governance section is probably too vague given the wide range of policies that the Strategy proposes. Moreover, the absence of Key Performance Indicators for evaluating the policy initiatives and of a roadmap for their implementation are clear weaknesses of the document, which overall seriously harm its success.

3.3 Sailing in turbulent waves? An overall assessment of the implementation risks of the Italian AI Strategy

The new Italian AI Strategy is a synthetic and rationally designed programmatic document. By rationally designed I mean that it soundly addresses the main weaknesses of the Italian AI ecosystem (talent attraction, little scale in research, small industry adoption and market size, limited usage in public services) and proposes targeted solutions.

I already mentioned some critical issues arising from the document:

-

The drafting of the proposal has not involved many professionals outside of Computer Science Academics;

-

The policy proposals on the “Talent and skills” area are only focused on the next generation of workers, leaving behind those currently employed and the general population;

-

There is no information on which parameters will be used to monitor the Strategy implementation advancement, in general the “governance” section is strikingly vague.

Despite the above, it is fair to say that the Italian AI ecosystem will benefit from the proposed policies. However, it is crucial to address some serious risks that hamper the implementation of the strategy. First of all, I should state that none of the provisions listed in the Strategy is binding as I am only dealing with a plan and not with regulation of any sort.

There is an excessive reliance on the NRRP (National Recovery and Resilience Plan, PNRR in Italian). It is appreciable that for most of the policies there is some funding indication, however—rather than relying on ad hoc resources—14 out of 24 policy measures are supposed to be funded by the Recovery Plan (8 are not associated with funding opportunities, 2 are supposed to be funded by other programs). It needs to be underlined that the funding resources mentioned in the Strategy are not exclusively arranged for AI-policy initiatives. This will lead to a “competition” between policy themes/issues to go after the best possible share of the Recovery Plan funds. For instance, the PNRR allocates 1.580 M€ for setting up “an integrated system of research and innovation infrastructures”: this funding source is indicated by the Strategy to fund the aforementioned “AI Research Data and Software Platform”, however the resources could potentially be allocated to fund other technologies outside of AI.

Moreover, the Strategy does not provide any clear indication about a possible roadmap for its implementation. The title “Strategic Program on Artificial Intelligence 2022–2024” suggests that the implementation of all 24 policy initiatives should start between 2022 and 2024, it is not clear which ones—if any—will be prioritised.

Lastly, it is very important to notice that the Italian political context is expected to become more turbulent as the 2023 elections approach, which adds up to the Italian “endemic” political instability. The Draghi Cabinet—who is ultimately responsible for the Strategy—is a caretaker and partially-technocratic government that, likely, will not stay in place after the elections. It is to be noted that theoretically it is possible that Mario Draghi could be appointed as Prime Minister even after the 2023 elections, however it will have to form another cabinet (Draghi II) which will most likely be different from the current one. It is also not given that the Ministry of Technological Innovation and Digital Transition will continue to exist (given the fact that it is a without portfolio Ministry that – in order to continue to operate—shall be re-established by the new Prime Minister cabinet after the 2023 elections). These changes ahead make the governance of the strategy more difficult, as it is possible that the political will to pursue its goals will vanish. On the other hand, it is possible to speculate that external pressures (the EU) and internal influences (e.g., trade associations) will “push” Italian institutions to go further in the implementation of the Strategy. Therefore, I ask myself: will we be salvati dall’Europa (Rescued by Europe) [18] again? It is to be noted that this book refers to the EU pressure on developing modern welfare reforms in Italy. Here we just use it as an example on external influence on internal policymaking.

A further consideration is on the role that industry will be playing. Government approach is mainly top down by enforcing regulations, defining frameworks and sustaining/steering industry and institutions through financial support (de-fiscalisation, industrial research funding, fostering competence acquisition, etc.). On the other hand, industry approach is bottom up, looking at the market to generate revenues. These two approaches need to reinforce one another rather than contrasting with one another. The challenge, and the objective of a national AI strategy is to make these two approaches consistent with one another. Industry Associations, like Anitec Assinform, endeavor at bridging the bottom up and the top down approach.

3.4 Promoting the creation of AI in the Italian industrial landscape

Data is a fundamental part in the creation and operation of artificial intelligence applications. The emergence of new AI algorithms like the previously mentioned GAN—Generative Adversarial Networks- that can operate on smaller subset of data streams and the parallel availability of transformers, like GPT-3, GLaM, and of synthetic data opens up the AI game, and applicability, to a variety of SMEs. The data availability remains crucial, and in particular the availability of usable data. This is what has prompted the EU to support the GAIA-X initiative and in turns moved several enterprises to join the initiative and a few Governments, among these the Italian one, to support the creation of GAIA-X national hubs with the goal to develop data spaces.

The Italian Government has indicated as priority for national data spaces the ones on: circular economy, fashion, health & wellbeing, tourism and culture, manufacturing, mobility.

4 Future scenarios

As noted in the previous sections, Italian Industry is varied in size and in products areas. It is therefore challenging to provide a “one-fits-all” scenario of evolution. There are, however, some commonalities that will play a role in steering the global evolution affecting each and every companies:

-

The National Recovery Plan is requesting the Digital Transformation of the Public Administration and companies that have to relate with the Public Administration will be forced to operate in the cyberspace;

-

The National Recovery Plan fosters the Digital Transformation of the Private sector supporting it with funding for training and cutting-edge equipment.

The Italian Government has designed an AI strategy, presented in the previous section. This goes hand in hand with the European measures (strategy, regulation, standardization). Companies will both be motivated in using and exploiting AI as well as feel compelled, in certain areas, to use it to stay in step with European evolution that is both a marketplace and a competition arena. Furthermore the increasing volume of data will soon become impossible to manage without the support of AI tools forcing their adoption.

In addition to the above forces steering the adoption of AI I am expecting:

-

Increased availability of skilled resources from both University and ITS, high level technical schools, where AI will become part of the curricula

-

Higher availability of easy to use tools to create AI in house using low-code / no-code technologies

-

Commoditization of GPT-3/GLaM and Gopher to train AI applications leveraging on company data

In order to stimulate further discussion, I propose three possible outcomes on the interaction between the context outlined in Sect. 2 and the National AI Strategy addressed in Sect. 3.

4.1 Optimistic scenario

A small subset of industries will take the lead in the use of AI and will act as “evangelists” to promote its adoption. This will be flanked by a public administration that will adopt AI and will require its customers (industries/citizens) to go along with the wave, providing applications and access to data -Open Data Framework. These two concurrent actions will rapidly involve more and more companies leading to an AI based ecosystem that will make the generation of AI based services attractive to many players. By the end of this decade AI will become a common tool for business and citizens alike. The Government will set up a regulatory framework promoting AI application, data privacy will be preserved by transferring the data control to the owning party (hence citizens data will be owned by the individual citizen that, through the Personal Digital Twin will decide -also based on the mandated data sharing framework- who, how and when can get access to data; similarly, for companies owned data).

4.2 Realistic scenario

Several industries will keep increasing their adoption of AI and will be spreading it through their value chains (supply/distribution). A solid contribution to adoption in their value chain. System integrators and process supporting tools providers that will be using AI in their products will be the major force in introducing AI in medium and small enterprises. The reshaping of industry, and the related adoption of AI, will be fostered by external parties that will be using common building blocks for their offer to the effect of inducing an uptake in the market over a slightly longer period of time. The Public Administration will be adopting AI internally, mostly through acquisition of tools with embedded AI but will not disclose data, hence not playing a positive role in the adoption by private players, nor it will require private players to use AI in their interaction with the public administration. Government regulation on AI will be conservative, more focused on avoiding issues than on stimulating adoption and innovation. Small companies not participating in broad ecosystems may remain excluded by the adoption of AI and the possibility to leverage on data.

4.3 Pessimistic scenario

AI will remain embedded in tools and applications bought off-the-shelf by most companies, including its usage in the Public Administration, hence although its use will keep growing it will not generate a snowball effect fostering further adoption. In most cases it will remain invisible and will not lead to changes in data policies) companies will not be interested in leveraging on data).

The AI related knowledge will not become part of companies’ knowledge, as today’s transistors knowledge are not part of most companies knowledge even though they are spread and used everywhere.

AI will not be leveraged to increase the portfolio offer. Government will be focusing on data privacy rather than on data exploitation. The industrial and business sector will, by far, remain tied to the physical space in terms of activity and organization.

5 Conclusions

Italy has proved over and over very strong resilience and the capability of its SMEs to adapt to a changing market environment. A good portion of Italian industry output is directed to the international market and remaining competitive in that market forces the national industry to adopt whatever is needed to match, and exceed, competition.

Artificial intelligence is becoming a tool of the trade. It is no longer the walled garden of a few (large) companies that can create AI from their huge data sets and processing power. The trend is towards commoditization of data infrastructures (easy, affordable access to data and to processing resources) and AI at its basic level is also becoming a commodity (already true for Natural Language Processing, Speech syntheses, etc. and becoming so for Image Recognition…).

The new landscape for AI will see the emergence, and exploitation, of a distributed AI infrastructure, as well as the emergence of local intelligence fostered by affordable (micro)chips platforms and synthetic data.

In this new landscape competition shifts from the adoption of AI to the integration of AI as well as the leverage of IA (Intelligence Augmentation). The pervasive adoption of (intelligent) Digital Twins and the rising interest in Cognitive/Personal Digital Twins supporting a massive distributed and executable knowledge may create the backstage for SMEs to overcome current lack of skill. At the same time this requires a new generation of entrepreneurial capability that understands the benefits (and drawbacks) of AI and the way it can be leveraged.

Industrial Associations can play a significant role in this entrepreneurial cultural growth and can bridge industry needs with policy regulation, bringing bottom-up evolution to match top down frameworks.

The international and barrier free environment in which AI grows and evolves cannot be stopped by local trenches. Thinking that industry will not use available tools because a regulator said so is wishful thinking. Notice that the problem is not in the enforcing a regulation on a national company. The problem, and impossibility, in a democratic context is forcing users to stay within the regulated context. The web and web services know no border and users will go to where services meet their needs (and fancy). Industry has no choice but following the market.

Governments, on the other hand, have the responsibility of creating a culture that benefits the citizenship without hampering the business. These are not easy goals but are not impossible either.

The Italian AI Strategy, with all the caveats that I mentioned, is a good step forward and it will need to be tuned as time goes by, since evolution for AI and its usage has just begun.

The adoption of AI by national industry, as monitored by Anitec Assinform is showing both the gaps, particularly the adoption of AI as a tool to increase efficiency and not -also- as a tool to increase the offer portfolio, thus making companies competitive in pricing but not competitive in features offering, as well as the ever-stronger interest in AI by SMEs and the role played by systems integrators. To these lay the responsibility of delivering products that change users processes and evolve their culture. A bottom-up evolution that coupled by a hopefully effective top down approach in evolution of the Public Administration will keep Italy competitive on the international market. This seems to us a more reasonable -and useful- goal than the one of becoming “leader in AI”.

References

European Commission. Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology, European enterprise survey on the use of technologies based on artificial intelligence: final report, Publications Office, 2020. Doi: https://doi.org/10.2759/759368

Anitec-Assinform. White paper: Promuovere lo sviluppo e l’adozione dell’Intelligenza artitificiale a servizio della ripresa. Anitec-Assinform 2021. https://www.anitec-assinform.it/kdocs/2010991/white_paper_intelligenza_artificiale_anitec-assinform.pdf

Anitec-Assinform. L’IA a tre dimensioni: approfondimenti su policy, tecnologie ed esperienze aziendali. https://www.corrierecomunicazioni.it/tag/lia-a-tre-dimensioni-approfondimenti-su-policy/

The Second White paper, published by Anitec-Assinform, April 2022. https://d110erj175o600.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/20151324/WP_IA_20042022.pdf

Proposte per una Strategia italiana per l'intelligenza artificiale, Ministero dello sviluppo economico, Elaborata dal Gruppo di Esperti MISE sull’intelligenza artificiale, 2020. https://www.mise.gov.it/images/stories/documenti/Proposte_per_una_Strategia_italiana_AI.pdf

Van Roy V. AI Watch-National strategies on Artificial Intelligence: a European perspective in 2019,” 2020.https://doi.org/10.2760/602843

Dutton T. An overview of national AI Strategies.” Politics + AI (Blog). 2018, June 28. https://medium.com/politics-ai/an-overview-of-national-ai-strategies-2a70ec6edfd. Accessed 23 Apr 2022

OECD.AI (2021), powered by EC/OECD (2021), database of national AI policies, accessed on March 27, 2022. https://oecd.ai

Italian Observatory on AI, 2021, Il Mercato 2020 dell’Artificial Intelligence in Italia: Applicazioni e Trend di Sviluppo. https://www.osservatori.net/it/ricerche/comunicati-stampa/mercato-artificial-intelligence-italia

Anitec-Assinform, Il Digital in Italia 2021 vol 1–2. https://www.anitec-assinform.it/comunicati-stampa/scheda-dati-rapporto-anitec-assinform-il-digitale-in-italia-2021-vol-1.kl. https://www.anitec-assinform.it/in-evidenza/scheda-dati-rapporto-anitec-assinform-il-digitale-in-italia-2021-vol-2.kl

Italian Observatory on AI, 2022, Il Mercato 2021 dell’Artificial Intelligence in Italia: Applicazioni e Trend di Sviluppo. https://www.digital4.biz/executive/artificial-intelligence-intelligenza-artificiale

Strategia Nazionale per l’Intelligenza Artificiale, Sept. 2020. https://www.mise.gov.it/images/stories/documenti/Strategia_Nazionale_AI_2020.pdf

“Artificial Intelligence: Italy launches the national strategy,” MITD, 2021. https://innovazione.gov.it/notizie/articoli/intelligenza-artificiale-l-italia-lancia-la-strategia-nazionale/

European Commission. Excellence and trust in artificial intelligence, February 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/fs_20_282

Kazim E, Almeida D, Kingsman N, et al. Innovation and opportunity: review of the UK’s national AI strategy. Discov Artif Intell. 2021;1:14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-021-00014-0.

Bareis J, Katzenbach C. Talking AI into being: the narratives and imaginaries of national AI strategies and their performative politics. Sci Technol Hum Values. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211030007.

European Commission. Digital Economy and Society Score—Italy 2021.

Ferrera M, Gualmini E. Salvati dall'Europa?. Vol. 110. Il mulino, 1999.

Redazione MU. 2022 Meccanica NCWS. IA e PMI: c’è ancora molto da fare

AI HLEG. AI high level expert group EU. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/expert-group-ai

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge the tremendous help I received from Ettore Russo, Junior Policy Advisor in Anitec Assinform, in writing this paper, and even more in coordinating the AI group of the Italian IT industries through-out the last 18 months. Without his dedication and support I would have not taken up the challenge to provide a summary of the AI Italian landscape.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I have provided information that is derived from my work within the DRI IEEE Initiative and the one derived from leading the AI workgroup of the Italian Industry Association Anitec Assinform.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saracco, R. Perspectives on AI adoption in Italy, the role of the Italian AI Strategy. Discov Artif Intell 2, 9 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-022-00025-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-022-00025-5