Abstract

Background

Among individuals with heart failure (HF), racial differences in comorbidities may be mediated by social determinants of health (SDOH).

Methods

Black and White US community-dwelling participants in the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study aged ≥ 45 years with an adjudicated HF hospitalization between 2003 and 2017 were included in this cross-sectional analysis. We assessed whether higher prevalence of comorbidities in Black participants compared to White participants were mediated by SDOH in socioeconomic, environment/housing, social support, and healthcare access domains, using the inverse odds weighting method.

Results

Black (n = 240) compared to White (n = 293) participants with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) had higher prevalence of diabetes [1.38 (95% CI 1.18–1.61)], chronic kidney disease [1.21 (95% CI 1.01–1.45)], and anemia [1.33 (95% CI 1.02–1.75)] and lower prevalence of atrial fibrillation [0.80 (95% CI (0.65–0.98)]. Black (n = 314) compared to White (n = 367) participants with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) had higher prevalence of hypertension [1.04 (95% CI 1.02–1.07)] and diabetes [1.26 (95% CI 1.09–1.45)] and lower prevalence of coronary artery disease [0.86 (95% CI 0.78–0.94)] and atrial fibrillation [0.70 (95% CI 0.58–0.83)]. Socioeconomic status explained 14.5%, 26.5% and 40% of excess diabetes, anemia, and chronic kidney disease among Black adults with HFpEF; however; mediation was not statistically significant and no other SDOH substantially mediated differences in comorbidity prevalence.

Conclusions

Socioeconomic status partially mediated excess diabetes, anemia, and chronic kidney disease experienced by Black adults with HFpEF, but differences in other comorbidities were not explained by other SDOH examined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

In the United States, individuals with heart failure (HF) often have multiple comorbid chronic conditions that impact health and quality of life [1,2,3]. Common comorbidities among people living with HF include cardiovascular conditions such as coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, and stroke [3,4,5,6,7], and non-cardiovascular comorbidities such as diabetes, anemia, chronic kidney disease, respiratory disorders, and depression [5, 8,9,10,11,12]. These comorbidities impact HF clinical management by increasing risk of hospital readmissions [13], functional decline [14], and mortality [15]. Additionally, multiple chronic conditions require management often by multiple physicians, which increases healthcare utilization and costs [16, 17].

While > 80% of HF patients have more than two additional comorbidities [3], the prevalence of comorbidities vary by race [18]. The etiology of HF and the prevalence of comorbidities also vary by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) [3]. Black patients experience higher rates of hospitalization and mortality due to HF [19,20,21], and more likely to report diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and stroke compared to White individuals with HF [22]. Guided by both the National Institute on Minority Health and Health disparities (NIMHD) and the Healthy People 2030 framework [23, 24], we posit that one explanation for this finding could relate to deleterious social determinants of health (SDOH), which are more commonly experienced by people of color in the United States (US). Notably, SDOH, which include the characteristics of the social, policy, and physical environments that influence health, may increase the likelihood of exposure to risk factors such as physical inactivity, obesity, and limited access to quality healthcare [20]—all of which contribute to comorbidity accumulation. Additionally, SDOH may also influence self-care activities including adherence to medication, consuming a heart healthy diet, and engaging in physical activity [21]. Although the relationships between SDOH and HF have been extensively studied, there are significant gaps in our understanding about how SDOH impact a range of heart failure outcomes [25]. Existing studies have primarily focused on the relationship between SDOH and mortality or survival rates, as well as hospital readmissions [25]. The disproportionate burden of HF and its poor outcomes in Black patients, is likely explained by racial differences in both SDOH and comorbidity prevalence. An understanding of comorbidity burden and SDOH among individuals with HF may improve health outcomes by providing insight to contextual factors that may be driving health inequalities between Black and White people with HF. These insights may also facilitate policy-driven risk stratification and the allocation of health promotion interventions for the management of HF and its comorbidities. Hence, we sought to examine racial differences in comorbidities between Black and White adults with HF in the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study and assess the role of SDOH in mediating any observed disparities.

2 Methods

2.1 Study population

REGARDS is a national longitudinal cohort study of 30 239 Black and White US community dwelling adults initially designed to examine contributors to geographic and racial differences stroke mortality [26]. Individuals aged 45 years and older were recruited into REGARDS in 2003–2007 with oversampling of Black individuals and in the Southeastern region of the US. Participants were enrolled through telephone screening and interviews to collect data on risk factors, medical history, demographics, environmental and psychosocial factors. Subsequent in-person physical exams and blood and urine samples were obtained during home visits. At 6-month intervals, participants are interviewed over the telephone to identify potential strokes and other health events. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the REGARDS Study.

The current study included REGARDS participants with an adjudicated HF hospitalization between 2003 and 2017. The protocol for this study was assessed and approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Boards. The REGARDS study shares data with investigators through formal data use agreements. Requests for information on this process and data access may be sent to the REGARDS study at regardsadmin@uab.edu.

2.2 Detection and adjudication of HF hospitalization

During participants’ longitudinal telephone assessments, information on potentially heart-related hospitalizations was collected and medical records were retrieved and adjudicated through review of documented assessment of symptoms, physical examinations, laboratory and imaging results, medications, and treatments [27]. Medical records were reviewed by two independent clinical adjudicators. In the case of disagreements, final decisions were reached through discussion among investigators. For this analysis, we selected the last HF hospitalization during REGARDS study follow-up to obtain the most recent medical records and comorbidities history for each participant. A sensitivity analysis examined the first hospitalization during the REGARDS study follow-up (supplemental Table 4). We examined the relationships between race and comorbidities among participants with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) separately because prior work has shown differences in comorbidity prevalence based on heart failure subtype [3]. We defined HFpEF as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 50% or normal systolic function reported qualitatively. We defined HFrEF as LVEF < 50% or abnormal qualitatively reported systolic function [3]. We grouped heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) with HFrEF given shared pathophysiologic mechanisms [28]. There were 533 participants with HFpEF based on LVEF (n = 530) or normal systolic function reported qualitatively (n = 3), and 681 participants with HFrEF based on LVEF (n = 680) or abnormal qualitatively reported systolic function (n = 1) [28]. Participants who had HF hospitalizations without documented LVEF (n = 378) were included in analyses of the overall sample.

2.3 Identification of comorbidities

Comorbidities were grouped into cardiovascular (hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, and atrial fibrillation) and non-cardiovascular [diabetes, anemia, depression, chronic kidney disease (CKD), respiratory disorders [asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)] comorbidities. The specific comorbidities were chosen based on previous literature showing the prevalence and importance for clinical outcomes of these individual conditions among participants with HF [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12], as well as the availability of data in the REGARDS study population.

Comorbidities were considered present if they were reported or detected during baseline REGARDS data collection or documented in participant’s medical records at the time of HF hospitalization. A combination of self-report, medications and laboratory test results were used to identify baseline hypertension, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, stroke, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Anemia and respiratory disorders were assessed only from HF hospitalization medical records because they were not assessed during the REGARDS baseline data collection. At baseline, a participant was considered hypertensive if they had a systolic blood pressure of ≥ 130 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 80 mmHg or self-reported use of blood pressure lowering medication. Coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation at baseline were defined based on self-report or by evidence on an electrocardiogram (ECG). Diabetes at baseline was considered present if a participant had a fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL (or non-fasting glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL). In addition to laboratory test results for glucose, the use of insulin or diabetes mellitus medications as reported by participants were used to identify cases of diabetes mellitus. Chronic kidney disease at baseline was defined as self-reported dialysis or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Baseline stroke was self-reported [29]. Depressive symptoms was assessed at baseline using a 4-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) score ≥ 4. Chronic comorbidities documented in medical records from the HF hospitalization were recorded using a standardized medical record abstraction form by trained research assistants supervised by a clinician-investigator.

2.4 Race and social determinants of health

Race was self-reported by participants in this study [30]. The Healthy People 2030 conceptual framework [23], which outlines five distinct domains of SDOH, guided our evaluation. Based on the information available from the REGARDS Study, we adapted the model to create four domains covering seven deleterious SDOH including: socioeconomic status [level of education (< high school education) and low annual income (< $35,000), neighborhood/environment [Neighborhood poverty level (operationalized as participants living in a zip code with > 25% of residents living below poverty line), and rural residence (operationalized as participants living in large, small, or isolated rural areas)] [31], social support [operationalized as marital status [32]] and healthcare access [operationalized as residence in a complete Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA) and poor public health infrastructure areas (PPHI)]. In our adapted model, socioeconomic status and social support domains are connected to individual-level SDOH, while neighborhood/environment and healthcare access domains are related to community-level SDOH [33].

County-level HPSA was determined using the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) poor primary care services criteria: in those areas with need to delivery primary care in the specified areas or have a population to primary care provider ratio greater than 3500:1 ratio or for areas of heightened health care needs, a ratio greater than 3000:1, or have inadequate access to primary care in nearby locations. Complete health professional shortage area (HPSA) counties were those areas where the entire county had a HPSA classification. Partial HPSA counties were those areas where only a single entity had a HPSA designation but not the entire county or census tract. Consistent with other previous assessments on HPSA, participants who were from complete HPSA were compared to those who were from counties not designated as complete HPSA (partial and non-HPSA) to improve interpretability in mediation analysis [34]. We obtained PPHI measures from state-level rankings that established lifestyle, access to care and disability contributions collated by America’s Health Ranking [35]. We assigned a state as PPHI when they fell below the lower 20th percentile for their rankings for 8 or more years between 1993 and 2002 [35].

2.5 Covariates

Participant age at time of HF hospitalization and sex were selected as covariates for this study. Age was calculated based on participant’s date of birth.

2.6 Statistical analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics by ejection fraction (HFrEF versus HFpEF) and race. The proportion of participants with each of the comorbidities overall and by race was computed. To assess differences in individual comorbidities between Black and White participants, Poisson regression models with robust variance estimators adjusted for age and sex were adopted to estimate prevalence ratios (PR) and their associated 95% confidence intervals.

To assess the role of SDOH in explaining the greater prevalence of some comorbidities in Black participants with HF, the distribution of the SDOH were first examined by race and type of HF (see supplemental Table 1). The SDOH were further tested to see if they were associated with individual comorbidities. Selecting SDOH that were associated with both race and the comorbidities, we performed a mediation analysis by using the inverse odds weighting method [36, 37], to assess how much of the racial differences in each the comorbidities was explained by the SDOH domains. This methodology allowed for the inclusion of single or multiple mediators for the estimation of the impact of each SDOH component on the comorbidity among White and Black participants with HF. Mediation analysis was performed in the overall sample (including participants with undocumented ejection fraction) and by LVEF (HFrEF and HFpEF). Details regarding the implementation of inverse odds probability weighting are provided in Supplementary Table 9. Lastly, due to differences in assessment of comorbidities from the study baseline and during HF hospitalization up to 14 years later, a sensitivity analysis that included only comorbidities documented on medical records from the HF hospitalization was conducted. A 2-sided test for hypothesis and a p value < 0.05 for statistical significance was used for this study. We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for data analysis [38].

3 Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

Among 30 239 REGARDS participants, we excluded 27 954 participants for not having an adjudicated HF hospitalization, and 191 for missing baseline information on SDOH (Fig. 1, supplemental Table 1). The final study sample contained 1 592 unique participants and primary analyses were based on the most recent HF hospitalizations (median time to HF hospitalization was 2181 days from baseline).

Among participants with a HF hospitalization (HFpEF: n = 533, HFrEF: n = 681, LVEF not recorded n = 344), the median age was 79 (IQR: 73–85) years for White participants and 74 (67–80) years for Black participants (Table 1). For both HFrEF and HFpEF, compared to White participants, a greater proportion of Black participants in this study were women and Black adults were more likely to report having less than high school education and to live in ZIP codes with high poverty. A greater proportion of White adults lived in locations deemed complete healthcare provider shortage areas compared to Black adults.

3.2 Distribution of comorbidities by race

Among all participants with HF, 88.3% had at least 3 additional chronic conditions present at the time of their HF hospitalization (Table 2). Black adults were more likely to have 3 or more comorbidities compared to White participants (90.1% vs. 88.5%). Overall, Black participants had a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and anemia, and a lower prevalence of coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, depression, and respiratory disorders compared to White participants. Among participants with HFpEF, Black participants had a higher prevalence of diabetes (PR: 1.38, 95% CI 1.18–1.61), and anemia (PR: 1.33, 95% CI 1.02–1.75), and a lower prevalence of coronary artery disease (PR: 0.88, 95% CI 0.77–1.01), and atrial fibrillation (PR: 0.80, 95% CI 0.65–0.98), compared to White participants, adjusting for age and sex (Table 3). Among participants with HFrEF, Black adults had a higher prevalence of hypertension (PR: 1.04, 95% CI 1.02–1.07), and diabetes (PR: 1.26, 95% CI 1.09–1.45), and a lower prevalence of coronary artery disease (PR: 0.86, 95% CI 0.78–0.94), and atrial fibrillation (PR: 0.70, 95% CI 0.58–0.83) compared to White adults.

Associations were similar when we only included comorbidities documented in the medical records from the HF hospitalizations and when we examined the first HF hospitalization during study follow-up (supplemental Tables 3–5).

3.3 Race and comorbidities: mediation by social determinants of health

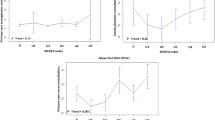

Among participants with HFpEF, income and education jointly mediated 14.5%, 26.5% and 40% of the excess diabetes, anemia, and chronic kidney disease in Black participants compared to White participants (supplemental Table 8). However, the mediation was not statistically significant (Fig. 2). There was no other substantial or statistically significant mediation of disparities in comorbidities by other domains of SDOH in the overall sample or by ejection fraction (Supplemental Tables 6–8). The individual associations between each SDOH and race, as well as between each SDOH and the comorbidities among participants with HF, are presented in Supplemental Table 2.

Mediation of the difference in the prevalence of comorbidities between Black and White participants with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction by socioeconomic status (Total effect is the age and sex adjusted prevalence ratio; the indirect effect is the association explained by socioeconomic status, and the direct effect is the association not explained by socioeconomic status)

4 Discussion

In a community-based population of White and Black individuals hospitalized with HF, we found racial differences in the patterns of comorbidities. Of all the SDOH examined, only income and education partially mediated the observed diabetes, anemia, and chronic kidney disease disparity among participants with HFpEF; however, this mediation was not statistically significant.

Comorbidities among patients with HF impact healthcare utilization by increasing risk of admission and healthcare needs [39]. Consistent with previous studies, we observed a high burden of comorbidities in this population [3, 40, 41]. Black adults with HFpEF particularly had a higher burden of non-cardiovascular diseases including chronic kidney disease, anemia, and diabetes compared to White individuals. This finding highlights the need both for clinical interventions that take these chronic conditions in HF patients into account, and also for coordinated care delivery models that are patient-centered and address multiple care needs.

Race is often employed as a poor proxy for social influences that can impact health outcomes, however, systemic and structural factors including structural racism and discriminatory practices in healthcare and other systems, drive many of the observed racial disparities in both health outcomes and SDOH [42, 43]. In this study, we examined whether racial disparities in SDOH in socioeconomic, environment/housing, social support, and healthcare access domains explained differences in comorbidities between Black and White individuals. Of the SDOH examined, only socioeconomic status (income and education) seemed to substantially (though not statistically significantly) mediate differences in diabetes, anemia, and chronic kidney disease among individuals with HFpEF. We did not find substantial mediation of SDOH in HFrEF. This may be because of the relatively modest differences in the prevalence of comorbidities by race in this study of individuals, all of whom had been hospitalized with HF.

While education has been associated with several poor health outcomes, poor education may also reproduce health inequalities and restrict access to better contextual determinants that influence long term outcomes [44]. For instance, a contextual determinant that can influence long term outcomes include access to primary and secondary prevention. For settings with favorable SDOH, these interventions may be readily available and applied more rapidly to prevent further deterioration and accumulation of deficits and comorbidities. These interventions may also be less likely to be available to individuals with poor SDOH due to the racialized access to quality health care that are determined by SDOH such as low education [45]. Additionally, individuals with higher education have been reported to have a lower risk of heart disease, however, the effect of higher educational attainment on reducing risk of poor outcomes was more pronounced among non-Hispanic White individuals than in Black adults [46]. Therefore, other considerations may be that education is not merely a means to wealth accumulation and opportunities but may interact with other domains of SDOH to impact health outcomes.

Black adults in the United States are more likely to experience adverse SDOH compared to White individuals [47]. Furthermore, adverse SDOH may expose at-risk groups to vulnerabilities and risk factors such as physical inactivity, poor access to healthy food, and quality healthcare. Additionally, continuing contact with the health system, which is crucial for HF management, may be delayed or halted due to other competing social needs and neighborhood level barriers to seeking care. Higher income and better educational attainment are generally associated with better quality of life [48, 49]. Favorable SDOH also affords people the opportunity to access better preventive services, manage chronic conditions more efficiently, and subsequently reduce the prevalence of comorbidities [50, 51]. Our findings, although not statistically significant, suggest a potential role of income and education in influencing the prevalence of comorbidities in participants with HF. Higher income and education can lead to better access to health care, adherence to guideline directed medical therapies and interventions, and more resources to manage chronic diseases thereby reducing the prevalence of comorbidities.

An important consideration, as stated earlier, calls for an in-depth and holistic assessment of other factors as well. The synergistic influence of these SDOH (poor income and education), can also produce greater levels of cumulative disadvantages, while severely limiting access to resources to promote recovery and long-term survival for patients with HF. Although beyond the scope of the current analysis, there may be disparities in the advantages from higher incomes and education between Black and White individuals, relating to the concept of diminishing returns for SES. For example, Ciciurkaite found that higher education and income were associated with a decrease in BMI for White individuals but not for Black individuals [52]. Other factors, including interpersonal discrimination and systemic and structural racism, may interact and impact the positive health impact that could have occurred. This highlights the need for further surveillance for social vulnerabilities that may be driving health disparities for patients with HF.

The strengths of this study include the relatively large sample of Black and White adults hospitalized with HF from across the United States and the use of participant examinations, interviews, and medical record review to identify comorbidities. We also examined a number of SDOH potentially driving the racial differences we observed and have provided these results by LVEF subtype. However, our study is not without some limitations, which should be considered when interpreting our results. Firstly, we only examined racial disparities in White and Black adults with HF. Other racial and ethnic groups were not included in the REGARDS study, and as such our findings may not be generalizable to other groups. The use of some measures such as the American Health Rankings may further limit generalizability to other areas and geographic locations not in the United States. Secondly, although our results suggest a 40% mediation effect for CKD and SDOH in participants with HFpEF, the lack of statistical significance we observed may have been influenced by power limitations and sample size. Among all the comorbidities examined, anemia and respiratory disorders were obtained from medical records, while all other comorbidities were accessed through the REGARDS study baseline data collection for our study participants. Therefore, we cannot be certain that the comorbidities (anemia and respiratory disorders) developed prior to the onset of HF. We have a single measure of SDOH at baseline; however, these characteristics may have changed by the time of HF hospitalization. We were not able to assess other potentially relevant SDOH including discrimination, the built environment, segregation, and structural racism. Finally, we cannot be sure that the exposure to the SDOH temporally preceded the development of the comorbidities. It is possible that development of comorbidities caused changes in the SDOH.

5 Conclusion

In this cohort of White and Black individuals hospitalized with HF, there were racial differences in the patterns of comorbidities overall and by LVEF. Income and education partially mediated the excess diabetes, anemia, and chronic kidney disease prevalence present in Black compared to White adults with HFpEF; other SDOH examined did not mediate differences in the prevalence of other comorbidities by race.

Data availability

The REGARDS study shares data with investigators through formal data use agreements. Requests for information on this process and data access may be sent to the REGARDS study at regardsadmin@uab.edu.

References

Warraich HJ, et al. Comorbidities and the decision to undergo or forego destination therapy left ventricular assist device implantation: an analysis from the trial of a shared decision support intervention for patients and their caregivers offered destination therapy for end-stage heart failure (DECIDE-LVAD) study. Am Heart J. 2019;213:91–6.

Joyce EMDP, et al. Variable contribution of heart failure to quality of life in ambulatory heart failure with reduced, better, or preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart failure. 2016;4(3):184–93.

Chamberlain AM, et al. Multimorbidity in heart failure: a community perspective. Am J Med. 2015;128(1):38–45.

Yancy CW, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147-239.

Lüscher TF. Heart failure and comorbidities: renal failure, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and inflammation. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(23):1415–7.

Adelborg K, et al. Risk of stroke in patients with heart failure. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1161–8.

Trevisan L, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of coronary artery disease in heart failure with preserved and mid-range ejection fractions: a systematic angiography approach. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;111(2):109–18.

Mentz RJ, et al. Noncardiac comorbidities in heart failure with reduced versus preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):2281–93.

Sbolli M, et al. Depression and heart failure: the lonely comorbidity. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(11):2007–17.

van der Wal HH, et al. Comorbidities in heart failure. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;243:35–66.

Ebong IA, et al. Mechanisms of heart failure in obesity. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2014;8(6):e540–8.

Lainscak M, Anker SD. Heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma: numbers, facts, and challenges. ESC heart failure. 2015;2(3):103–7.

Wideqvist M, et al. Hospital readmissions of patients with heart failure from real world: timing and associated risk factors. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8(2):1388–97.

Murad K, Kitzman DW. Frailty and multiple comorbidities in the elderly patient with heart failure: implications for management. Heart Fail Rev. 2012;17(4–5):581–8.

Screever EM, et al. Comorbidities complicating heart failure: changes over the last 15 years. Clin Res Cardiol. 2023;112(1):123–33.

McDaid D, Park AL. Counting all the costs: the economic impact of comorbidity. Key Issues Mental Health. 2014;179:23–32.

Valderas JM, et al. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):357–63.

Quiñones AR, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in multimorbidity development and chronic disease accumulation for middle-aged adults. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(6): e0218462.

Ziaeian B, et al. National Differences in Trends for Heart Failure Hospitalizations by Sex and Race/Ethnicity. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(7): e003552.

Nayak A, Hicks AJ, Morris AA. Understanding the complexity of heart failure risk and treatment in black patients. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13(8): e007264.

Heidenreich PA, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895–1032.

Cooper LB, et al. Multi-ethnic comparisons of diabetes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from the HF-ACTION trial and the ASIAN-HF registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(9):1281–9.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social determinants of Health. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health. Accessed 19 Sep 2021

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. NIMHD Research Framework. 2017. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework/nimhd-framework.html. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

Enard KR, et al. Influence of social determinants of health on heart failure outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(3): e026590.

Howard VJ, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(3):135–43.

Goyal P, et al. Prescribing patterns of heart failure-exacerbating medications following a heart failure hospitalization. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(1):25–34.

Butler J, Anker SD, Packer M. Redefining heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction. JAMA. 2019;322(18):1761–2.

National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Explaining your kidney test results: a tool for clinical use. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/professionals/advanced-search/explain-kidney-test-results.

Safford MM, et al. Number of social determinants of health and fatal and nonfatal incident coronary heart disease in the REGARDS study. Circulation. 2021;143(3):244–53.

Economic Research Service UDoA. Rural-urban community area codes. 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx.

Schultz WM, et al. Marital status and outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(12):e005890.

WHO. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. 2010. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852.

Brown TM, et al. Health Professional Shortage Areas, insurance status, and cardiovascular disease prevention in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(4):1179–89.

United Health Foundation. America’s health rankings. https://www.americashealthrankings.org. Accessed 5 Jan 2022

Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ. Inverse odds ratio-weighted estimation for causal mediation analysis. Stat Med. 2013;32(26):4567–80.

Nguyen QC, et al. Practical guidance for conducting mediation analysis with multiple mediators using inverse odds ratio weighting. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(5):349–56.

SAS Institute Inc. C, NC. https://www.sas.com/en_us/curiosity.html?utm_source=other&utm_medium=cpm&utm_campaign=non-cbo-us&dclid=&gclid=Cj0KCQjw7KqZBhCBARIsAI-fTKJElSUb1JXBVRWK5wTdaMcU1T5zPv2HKi81PgT2VyCDTfwslYm_2qMaAvesEALw_wcB.

Sharma A, et al. Trends in noncardiovascular comorbidities among patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circulation. 2018;11(6):e004646.

Loosen SH, et al. The spectrum of comorbidities at the initial diagnosis of heart failure a case control study. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):2670.

Sharma A, et al. Trends in noncardiovascular comorbidities among patients hospitalized for heart failure: insights from the get with the guidelines-heart failure registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(6): e004646.

Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35(4):407–11.

Churchwell K, et al. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American heart association. Circulation. 2020;142(24):e454–68.

Zajacova A, Lawrence EM. The relationship between education and health: reducing disparities through a contextual approach. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:273–89.

National Academies of Sciences, E. et al. in Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity, A. Baciu, et al., Editors. 2017, National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2017 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved: Washington (DC).

Assari S, et al. Diminished returns of educational attainment on heart disease among black Americans. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2020;14:5–12.

Javed Z, et al. Race, racism, and cardiovascular health: applying a social determinants of health framework to racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2022;15(1):e007917.

Jonsson M, et al. Inequalities in income and education are associated with survival differences after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: nationwide observational study. Circulation. 2021;144(24):1915–25.

Elfassy T, et al. Associations of income volatility with incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in a US cohort. Circulation. 2019;139(7):850–9.

White-Williams C, et al. Addressing social determinants of health in the care of patients with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2020;141(22):e841–63.

Mathews L, Brewer LC. A review of disparities in cardiac rehabilitation: evidence, drivers and solutions. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2021;41(6):375–82.

Ciciurkaite G. Race/ethnicity, gender and the SES gradient in BMI: The diminishing returns of SES for racial/ethnic minorities. Sociol Health Illn. 2021;43(8):1754–73.

Acknowledgements

This research project is supported by cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 co-funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health, and Human Service. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS or the NIA. Representatives of the NINDS were involved in the review of the manuscript but were not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at: https://www.uab.edu/soph/regardsstudy/. Additional funding was provided by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grants R01 HL80477 and R01 HL165452 and NIA grant R03 AG056446. Representatives from NHLBI and NIA did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project is supported by cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 co-funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health, and Human Service. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS or the NIA. Representatives of the NINDS were involved in the review of the manuscript but were not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at: https://www.uab.edu/soph/regardsstudy/. Additional funding was provided by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grants R01 HL80477 and R01 HL165452 and NIA grant R03 AG056446. Representatives from NHLBI and NIA did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ene M. Enogela, Parag Goyal, Elizabeth A. Jackson, Monika M. Safford, Stephen Clarkson, Thomas W. Buford, Todd M. Brown, D. Leann Long, Raegan W. Durant, and Emily B. Levitan conceptualized the study. Ene M. Enogela and Emily B. Levitan contributed to the data acquisition. Ene M. Enogela conducted the analysis. All authors interpreted the data. Ene M. Enogela and Emily B. Levitan drafted the original draft of the manuscript, while all authors critically revised the manuscript for clarity and accuracy. All authors read and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the REGARDS Study. The protocol for this study was assessed and approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Boards. The study was conducted in line with the principles outlined in the Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research.

Consent for publication

The REGARDS study has provided consent for the publications of these results and findings.

Competing interests

Dr. Emily B. Levitan receives funding from Amgen Inc.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Enogela, E.M., Goyal, P., Jackson, E.A. et al. Race, social determinants of health, and comorbidity patterns among participants with heart failure in the REasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. Discov Soc Sci Health 4, 35 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-024-00097-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-024-00097-x