Abstract

Exit is not an easy task for a sex worker. Academic investigations of the reasons and barriers to exit from the sex industry are lacking heavily. Sex work is a stigmatised profession, even though the workers find it difficult to exit the same. The current study attempted to understand the barriers faced by female sex workers in Puducherry, a union territory in the southeast part of India, to exit from sex work. The participants comprise 19 female sex workers (FSW) who work in Puducherry. The data were collected through in-depth interviews. All of the participants had thoughts about quitting. The barriers to exit were identified. The barriers were recognised at the individual, interpersonal (microsystem), and structural (macro system) levels within the framework of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, which are discussed in detail in the paper. The study also identified a lack of support systems for the targeted population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Exit is not an easy task for sex workers. Also, it is a process that should be considered and investigated with the same weightage as the entry and maintenance in sex work [1]. A little academic literature shed light on how sex workers leave the profession. Among the existing two approaches to exit from sex work, one focuses on the barriers to exit and the other on the internal factors linked to exiting the profession [2]. According to existing literature, there are three conclusions regarding exit from sex work. The vast majority of sex workers want to exit their profession, but ironically, they do not. Exiting is not a one-off process but is typified by stops and starts, which makes the process complex [3].

Exit theories provide different perspectives on how a person exits sex work. These models conceptualise the concept of exit with the help of various associated factors [1, 2, 4,5,6,7].

Mansson and Hedin [1] emphasise that a tipping point of negative experience results in contemplation and an attempt to exit. The theory emphasises social networks as an essential determinant of exit from sex work. At the same time, the phases of the lifestyle model by Williamson and Foloron [4] focus on exit from street prostitution. Exposure to violence, drug addiction, arrests, trauma, and other adverse events leads to attitude change, resulting in phases of disillusionment with the lifestyle of prostitution [4]. A more recent model, the typology of transitions model by Sanders [5], conceptualises the four transitions out of prostitution.

-

1.

Reactionary transition is when the woman experiences a life-changing event that sparks their departure.

-

2.

Gradual transition in which the woman starts to get formal support gradually and starts their progress

-

3.

Natural progression in which the woman develops a natural intrinsic desire to exit from sex work

-

4.

Yo-yoing, the woman drifts in and out of sex work, treatment centres and the criminal justice system [5].

Baker et al.’s [6] integrative model of exiting explains the stages of change in behaviour in which the final exit occurs after multiple attempts. This results in changes in identity, habits, and social networks. Many of the challenges women face in exiting prostitution arise from the lack of welfare and developmental approaches [6]. Baker et al. [6] have given an extensive review of the literature, which classified the barriers to leaving prostitution as individual, relational, and structural factors. Individual elements included self-destructive behaviour, substance abuse, mental health problems, the effects of trauma from adverse childhood, psychological trauma or injury from violence, chronic psychological stress, lack or poor self-esteem, shame, guilt, physical health problems, and lack of knowledge of services [6]. Relational factors include limited support, strained family relationships, pimps, drug dealers, and social isolation. Structural barriers to exit include employment, job skills, limited employment options, and basic needs such as housing, education, criminal records, and inadequate services. Finally, societal factors such as discrimination and stigma also act as barriers for sex workers to leave their profession [8].

Meanwhile, Cimino [7] provided a foundation for a testable theory based on synthesising existing theories and literature on exit from prostitution. She applied the Integrative Model of Behavioural Prediction (IMBP) to the context of exiting prostitution. This model incorporates the health belief model, social cognitive theory, the theory of reasoned action, and the theory of planned behaviour. It focuses on four elements: the action (exiting), the target (the woman), the context (street-level prostitution), and the period under which the behaviour is to be observed (e.g., permanently). Even though there is an overlap between existing models and IMBP, one distinctive difference is the emphasis on latent psychosocial variables underlying behaviour [7].

All these approaches illustrate the thoughts about exits that the majority of sex workers have. For many, this is also an unmet task. A women's motivations for leaving street prostitution, such as violence, drugs, and sharing physical closeness with strangers, may contend with women's reasons for staying in prostitution, such as drug addiction, low self-worth, a lack of social support, attachment to undesirable relationships, such as pimps, and financial independence [1, 4, 8]. Thus, the transition from prostitution is a conundrum. On the one hand, women were drawn into prostitution because of the failure or weakness of social institutions.

On the other hand, women worked hard to re-enter and negotiate spaces within the same social institutions after exiting prostitution, such as family, community, and the state. Exiting the sex industry does not always reduce social, economic, or emotional disadvantages. Women may continue to live restricted lifestyles without sufficient social and financial support [9].

“Easy money” can be said to be also the critical incentive and motive for going into, staying in, and returning to prostitution. Drugs or money for drugs are another advantage, which is a reality for on-street drug addicts. Even though people became more aware of the risks, the attention, lifestyle, and other benefits that made prostitution appealing could fade [10].

The major limitation of the existing literature is that it focuses primarily on street-based sex work. Research on exit perspectives in India is scarce. In addition, looking into all these barriers put forward by the existing literature points towards the importance of context and barriers at multiple levels.

Here is the importance of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological system theory in explaining the barriers at multiple levels. The microsystem, the mesosystem, the exosystem, the, the macro system, and the chronosystem are the five systems that Bronfenbrenner classified into an individual’s environment. Anything in a person’s immediate surroundings that comes into direct contact with them is the microsystem, the initial level of Bronfenbrenner’s theory. Interactions between several microsystems occur within the mesosystem. The exosystem consists of other formal and informal social institutions that are incorporated. The microsystems are nevertheless influenced by the exosystem, even though it does not directly communicate with the individual. The macro system focuses on the influence of cultural and social factors in one’s life. Chronosystem stands for the historical timeframe, events, and how they influence someone [11, 12].

The current study attempted to understand the barriers faced by female sex workers in Puducherry, a union territory in the southeast part of India, to exit from sex work. There was also an attempt to understand the barriers within the multiple levels proposed by Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological system theory. Coming to the context of sex work in Puducherry, the market for the sex industry was largely unexplored. In a comprehensive study conducted by the Ministry of Women and Child Development in 2004, the number of women or girls doing sex work in Puducherry Union Territory was estimated to be 1400 [13]. The current study focused not only on street-based workers but also primarily on indoor workers. It was expected to add knowledge to the existing research from indoor female sex workers’ perspectives.

2 Methods

2.1 Research design

The study employed an explorative qualitative research design to understand the phenomenon better. Since the matter of inquiry was to explore the barriers to exit from sex work, a how and why approach helped more than the quantification of the information. Also, the invisible and sensitive nature of the population points towards the appropriateness of the qualitative research design.

2.2 Participants

The qualitative study was conducted among 19 female sex workers (FSWs) who work in Puducherry union territory, India. The data were collected using in-depth interviews. A convenience sampling method was employed to select the participants from a readily available source for the researcher [14]. Since the study population was largely invisible and sensitive, randomisation was practically challenging in recruiting the participants. In that context, convenience sampling was the best way to find and recruit participants for the study. The age range of the participants was 19–48 years. The interview schedule was prepared before data collection and focused on their willingness to stay in or quit the sex industry and the barriers they are facing.

2.3 Procedure

The investigator approached the participants through a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) working with commercial sex workers named the Society for Development Research and Training (SfDRT) and made an appointment for the interview at the convenience of the Participants. The aim of the study was revealed to the participants, and the investigator established a rapport with them. The responses were noted using the audio recording at the participants’ convenience.

2.4 Tools used

The tool used for the current study was in-depth interviews. In-depth interviews are helpful when there is a small sample, and in-depth research of phenomena is needed. In the context of the current study, the nature of the data required was descriptive. The current interview schedule included open-ended questions related to the aspects of the barriers to exit from sex work. For example, “Have you ever thought of exiting from sex work?” What are the reasons for you to primarily stay in the sex work profession?”.

2.5 Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. The responses were translated from Tamil to English and transcribed in verbatim form. After the preparation of transcripts, the copies of the transcript were reviewed for accuracy by listening to the tape. It was checked whether the appropriate representation of the respondents’ thoughts matched the transcript, and, wherever necessary, corrections were made. Line-by-line coding was used. Then, it was analysed based on the systematic analysis of themes using the six-phase framework proposed by Braun and Clarke [15]. The themes were aligned within the framework of Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory. As part of reconceptualisation, the microsystem level barriers are renamed interpersonal and macro system level barriers as structural barriers. Each transcript was read and coded for the prominent themes. The themes were reviewed, or new themes were added based on the data.

2.6 Ethical consideration

Informed consent was taken from the participants before the interviews. The study details regarding the intention and procedure were briefed to the participants. The participants ensured anonymity and confidentiality. The participants were free to withdraw at any point in the study. The authors followed all the protocols and acquired permission for the study from the Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC), Pondicherry University (Ref. No. HEC/2019/02/03.09.2019). The study was conducted according to the guidelines of IEC, Pondicherry University.

3 Results

Table 1 shows that the age range of the participants was 19–48 (Mean = 33.42, SD = 8.22). Most are illiterate (N = 6) or studied up to 10th grade (N = 10). Three of the participants had completed 12th-grade education. Most are separated or abandoned (N = 10) and widowed (N = 2). Two participants are unmarried, and the rest are married (N = 5). The duration of sex work engaged by the participants ranges from 0.5 years to 20 years (Mean = 4.05, SD = 4.48). The modes of sex workers employed by the participants are indoor sex work (N = 16) and outdoor/street-based sex work (N = 3). All of the participants agreed that they have thoughts about quitting their profession.

3.1 Individual barriers

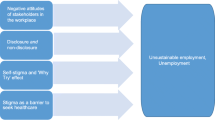

Figure 1 shows the barriers to exit from sex work at individual, interpersonal and structural levels. The individual-level barriers were conceptualised in a way that the factors within the Individual (demographics, cognitions and perceptions) about exiting from the sex industry. It includes a lack of partners, financial autonomy, and concern about children.

3.1.1 Lack of partner

Lack of a partner or unavailability of a partner, including irresponsible partners, was said to be a significant reason for staying in sex work. Most participants were either widowed, separated (legally or unmarried), or unmarried. Some of the verbatim responses which substantiate the same are given below:

“My family will not be able to get me married off. Now I cannot go for any other job either. Now that I have gotten used to it, it is fine for me. I do not have any hope about a better life” (Home based sex worker, 24)

“I have a feeling to get married again. I feel like someone should be there for me. It will be nice. If someone is ready to marry me, I will stop everything and live as a housewife”. (Home-based sex worker,38)

“My husband is a drunkard. Even if he is there also, we feel he is not there. He always causes trouble in the family. We are starving. How am I supposed to feed my family other than this?” (Home based sex worker, 24)

3.1.2 Financial autonomy

A few participants identified that after coming to sex work, they started feeling financial autonomy and economic freedom. Once they were out of the sex industry, they did not feel confident to have the same income.

“Now I don't need to depend on anyone for money. When my husband was working alone, most of the money he used for drinking alcohol. Me and my children were not taken care of by him properly” (Phone-based sex worker, 35).

“I have so much money which I was not able to earn from my previous work. Now I have a good dress, I can afford good food and a shelter” (Phone-based sex worker, 24).

3.1.3 Concern about Children

They were concerned about their children’s education and other expenses as a reason for continuing the profession. Many of them were considering quitting their jobs after their offspring got settled.

“All I want is a better life. Even if I suffer, my children should not have any difficulties” (Home-based sex worker, 37)

Some even consider that they can relax once their children attain a better future. Children were the primary hope of the majority of the participants.

“I will quit this job once children get settled. At least if my daughter gets matured also, I may quit because she should not come to this (sex industry) because of me” (Home-based sex worker, 27)

3.2 Interpersonal barriers (microsystem)

Microsystems represent the immediate environments that have constant interaction with the individual. The barriers at the microsystem level were identified as interpersonal barriers in this context, which were extramarital affairs of the partner and client-related factors.

3.2.1 Extramarital affairs of the partners

Extramarital affairs of the partners eventually led to abandoning the participants, and they reached financial difficulties.

“My husband was sitting at home without going to work. His business was at a loss. That is how I started this job. Now he got married to another woman and abandoned our children and me. Now I can’t find any other way to take care of my family” (Home-based sex worker, 35)

“My husband was ill. For finding money for his treatment only I came to this job. Later he started living with another lady with whom he was having an affair, and I got trapped with this job” (Street-based sex worker, 30).

3.2.2 Client related issues

Some CSWs mentioned that clients were not letting them get out of the profession. The clients kept contacting them for business, and the participants were unable to negotiate at some point.

“I want to quit the job and settle for a decent life. However, clients are not letting it come out. They continuously call and insist on having sex. So it is difficult to quit.” (Home-based sex worker, 38)

“Customers are not letting me stop this work. They plead and threaten sometimes. If someone comes to know about my job through any of my customers, it will be disastrous” (Home-based sex worker, 37)

3.3 Structural barriers (macrosystem)

The macro system, which consists of the social environments, cultural ideas, and attitudes an individual was exposed to, focuses on how cultural factors influence someone. The barriers identified at the macro system level were conceptualised as structural barriers, viz. stigma, re-entry, financial burden and lack of alternatives.

3.3.1 Stigma

Sex work is a stigmatised profession due to the sex taboo. The stigma associated with the profession was a haunting factor for them even after quitting, according to some CSWs. It was like, ‘Once you are a sex worker, you are always a sex worker’.

“Even after quitting this job, people won't give respect. They will be seeing me as a prostitute only” (Home-based sex worker, 37)

“Already I got a bad name. Even if I stop working, people will see me like that. Then why should I quit?” (Home-based sex worker, 35).

Some participants even thought there was no escape from the stigma.

“Death is the only way to come out of this job” (Home base sex worker, 35)

3.3.2 Re-entry

It was identified that some of the CSWs already quit their job, but they returned to work due to some circumstances.

“Once I left the job completely. But after a while, I restarted for the medical expenses of my husband” (Street-based sex worker, 30)

“Once I quit the job and went for some daily wage work. But the income was not enough, so I returned”. (Home-based sex worker, 34)

3.3.3 Financial burden

All of the participants mentioned some existing financial burden as a block for quitting sex work. All the participants in this study were hailing from lower socio-economic backgrounds. So, the existing financial burden forced them to stay in the sex industry.

“There is a lack of financial resources for me. So, if I quit, the whole family will be starving” (Home-based sex worker, 40)

“I am worried about what I will do if I quit this job. I have to build a home after having financial settlement” (Home-based sex worker, 23)

3.3.4 Lack of alternative livelihood

Many participants mentioned that the lack of alternative jobs was one of the reasons for sticking to sex work. A vast majority of the participants had low educational qualifications, which restricted their job opportunities.

“I have been searching for a job for a while, but not getting anything with the proper income” (Home-based sex worker, 27)

“My health is not in good condition. So, I can’t go for other jobs (Home-based sex worker, 40).”

Some participants even attempted other jobs, but they were not as earnable as sex work for them.

“Other works are scarce. I tried many other jobs, but there is not enough income” (Street-based sex worker, 48)

4 Discussion

Since sex work is a stigmatised profession, female commercial sex workers are not exiting the profession due to some reasons. They are broadly classified into three categories according to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological System theory: individual, microsystem and macrosystem levels. The microsystem level is reconceptualised as interpersonal barriers, and the system level is the structural barriers. Baker et al. identified relational and structural factors in their integrative exit model, which is connected to the current findings [6, 9]. CSWs decided to stay in the field because it pays more and gives them more flexibility than other types of employment [16].

Individual factors include a lack of partners, financial autonomy, and concerns about children. Many FSWs reported being widowed or separated when it came to their partners (legally or casually). Partners may be present in some situations, but their relationship may involve intimate partner violence. Despite the disproportionate burden of various challenges, a few participants identified certain positive aspects of their professions. A few participants identified that, after coming to sex work, they felt financial autonomy and economic freedom. CSWs remain engaged in sex work to get money to support family and daily needs and to get alcohol [17]. Flexible working hours and a good income were always attractive features of sex work, as cited in the literature [18, 19]. According to many FSWs, children are the only source of hope. They stay with their work to give their children a fulfilling life, including good education and nutrition.

Interpersonal (microsystem) level factors include the extramarital affair of the partner and client-related issues. Sometimes, clients’ persuasion and threats also hinder them from leaving their jobs. As discussed earlier, problems with partnerships also consist of their partners’ illegal affairs.

Structural (macro system) level factors include stigma associated with the profession, returning to work, current financial difficulties, and a lack of other viable employment options. The participants believed that because their field was stigmatised, even if they left the field, they would still see it negatively because of their line of work. Researchers have examined how stigma associated with sex work affects people’s personal, professional, and physical health and concluded that stigma itself causes social inequity [20].

Some FSWs have already left their occupations but have since returned because of problems with their partners’ health, a lack of capital from their other work, or their incapacity to find alternative employment. All participants reported their financial struggles, including debt, rent, and daily expenses. They can manage their current economic difficulties in some way thanks to the money from this occupation. With a higher income, employment is also problematic. Gadekar [21] investigated the socio-economic circumstances of sex workers in India's Mirage town. According to the research findings, most are classified as having a poor socio-economic position. Their lack of access to resources and illiteracy also contribute to their neglect of health issues [21]. Susan and Asir [22] also investigated the socio-demographic profile of Chennai's sex workers and found similar aspects.

Additionally, they mentioned sex workers’ lack of financial resources and heavy family obligations. Ingabire et al. [23] observed that women who described their occupation as risky did not abandon it primarily for economic reasons, supporting Cimino’s [7] conclusion that “easy money” was the primary incentive and motive for entering, continuing in, and returning to prostitution. Most of the FSWs in this study had a low educational status, contributing to not getting a better job. Therefore, women believed they could not obtain alternative employment because of inadequate education [9].

5 Conclusions and implications

The study identified barriers to exiting sex work as being primarily related to financial motives, the lack of alternative livelihoods, and the presence of children as a source of hope. To address these issues, a multilevel support system should include alternate employment and monetary strategies such as financial schemes, pensions, and children’s scholarships. It is also essential for society to become more aware of the rights of sex workers and treat them with humanity. Mental health practitioners and policymakers can use the findings of this study to develop comprehensive research- and need-based interventions. For instance, establishing a mental health support centre specifically for sex workers in an AIDS control society or government hospitals could be considered. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate support systems and policies in the Indian context.

6 Limitations and recommendations

The study addressed only female sex workers. The existing process of male and transgender sex workers is still at a blind spot. One-time interviews were taken for the study, but multiple interviews with the same participant would help to go more deeply about the issue. Future researchers can look into the issue considering these limitations.

The study strongly recommends tailor-made policies for sex workers, which is a need of the hour, such as financial assistance and rehabilitation centres for sex workers who wish to shift from their profession. Also, policymakers could stress making or amending existing policies while considering structural barriers. Also, in terms of future research, more context-specific interventional studies related to exiting the profession should be carried out.

Data availability

Due to its sensitivity, the data used for the current study is unavailable in any repositories. It is strictly kept confidential with the researchers and cannot be shared based on the participants’ request.

References

Månsson SA, Hedin UC. Breaking the Matthew effect—on women leaving prostitution. Int J Soc Welf. 1999;8(1):67–77.

Oselin SS. Weighing the consequences of a deviant career: factors leading to an exit from prostitution. Soc Perspect. 2010;53(4):527–49.

Mayhew P, Mossman E. Exiting prostitution: models of best practice. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Justice. https://www.nzpc.org.nz/pdfs/Mayhew-and-Mossman,-(2007c)-Exiting-Prostitution-Models-of-best-practice.pdf

Williamson C, Folaron G. Understanding the experiences of street level prostitutes. Qual Soc Work Res Pract. 2003;2(3):271–87.

Sanders T. Becoming an ex-sex worker. Fem Criminol. 2007;2(1):74–95.

Baker LM, Dalla RL, Williamson C. Exiting prostitution: an integrated model. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(5):579–600.

Cimino AN. A predictive theory of intentions to exit street-level prostitution. Violence Against Women. 2012;18(10):1235–52.

Weitzer R. Sociology of sex work. Annu Rev Sociol. 2009;2009(35):213–34.

Menezes S. A thesis on exiting prostitution: implications for criminal justice social work. Int J Crim Justice Sci. 2019;14(1):67–81.

Cimino AN. Uncovering intentions to exit prostitution: findings from a qualitative study. Vict Offenders. 2019;14(5):606–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2019.1628144.

Kloos B, Hill J, Thomas E, Wandersman A, Elias MJ, Dalton JH. Community Psychology: Linking Individuals and Communities. 3rd ed. wadsworth: cengage learning; 2012.

Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979.

Resettlement Scheme for Sex Workers. pib.gov.in. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=103218.

Andrade C. The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021;43(1):86–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620977000.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res in Psy. 2006;3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Azhar S, Dasgupta S, Sinha S, Karandikar S. Diversity in sex work in india: challenging stereotypes regarding sex workers. Sex Cult. 2020;24(6):1774–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09719-3.

Devine A, Bowen K, Dzuvichu B, Rungsung R, Kermode M. Pathways to sex work in Nagaland, India: implications for HIV prevention and community mobilisation. AIDS Care Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV. 2010;22(2):228–37.

Van Blerk L. Poverty, migration and sex work: youth transitions in Ethiopia. Area. 2008;40(2):245–53.

Bucardo J, Semple SJ, Fraga-Vallejo M, Davila W, Patterson TL. A qualitative exploration of female sex work in Tijuana, Mexico. Arch of Sex Behav. 2004;33(4):343–51.

Benoit C, Jansson SM, Smith M, Flagg J. Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives and health of sex workers. The J Sex Res. 2018;55(45):457–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652.

Gadekar U. Socio-economic status and health challenges of female sex workers of Miraj Town. India Int Res J Soc Sci. 2015;4(6):68–71.

Susan SL, Sam RM, Asir D. A study on life satisfaction among female sex workers. Indian J Appl Res. 2001;2014:22–4.

Ingabire MC, Mitchell K, Veldhuijzen N, Umulisa MM, Nyinawabega J, Kestelyn E, et al. Joining and leaving sex work: experiences of women in Kigali, Rwanda. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14(9):1037–47.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participants and the Non-government Organisation (NGO) staff ('Society for Development Research and Training' (SfDRT)) for their assistance in data collection.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PS: conceptualization, data collection and analysis, writing the article SD: conceptualization and guidance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Swathisha, P., Deb, S. Barriers for exiting sex work: an exploration on female sex workers (FSW) in Puducherry, India. Discov Soc Sci Health 4, 21 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-024-00080-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-024-00080-6