Abstract

Precariousness dominates the lives of patients with recent diabetic lower extremity amputations. Wound healing is not guaranteed, post-amputation mortality is high and personal and social identities are destabilised. This study explores the experiences of nine post-amputation diabetic patients in the context of Singapore’s primary health and social care and diversified cultural setting. The loss of physical integrity leads to the self being rendered precarious in multiple ways: emotional-existential precariousness results from uncertainty about survival; agentic precariousness, from restrictions to the individual’s autonomy; the social self is rendered precarious as social relations and identities are changed; and financial precarity, which arises from job insecurity and treatment cost. Patients act to overcome precariousness and regain agency in various ways. Supporting patients’ agency should be integral to all healthcare interventions, at whatever stage of the patient’s journey, and needs to take into account cultural roles and values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Precariousness and precarity have become common themes in sociology and healthcare research today. Following the publication of Judith Butler’s influential book Precarious Life in 2004 and protests by self-identified precariat in various countries in the first two decades of the millennium, both terms have been even more readily taken up by researchers of sociology, geography, labor studies and gerontology. Both terms are used to describe a situation of existential uncertainty marked by a lack of financial security, also implying a lack of physical, emotional, existential and social security [1,2,3,4]. Studies on the social determinants of health show the interplay between health, physical or mental illness, unemployment and precariousness [3, 5,6,7,8], although few of them examine the impact of specific illnesses on patients’ lives.

This article proposes that applying the conceptual lens of precariousness to the experience of patients with diabetic amputation is useful for gaining deeper insight into patients’ lived experience of the event; moreover, such an analysis allows us to uncover aspects of the concept of precariousness based upon lived experience.

2 Background

Diabetes is a leading cause of nontraumatic lower-extremity amputations globally, and such cases are on the rise. [9,10,11,12] Patients who undergo a diabetic lower extremity amputation (DLEA) owing to complications of diabetes often find their lives upended and drastically changed overnight. At best, patients resume their lives with a permanently altered body and self-concept [13, 14]; at worst, they face further amputations or even death. Diabetic amputations are far more susceptible to complications and less likely to heal than non-diabetic amputations. [15] Healing time is unpredictable, and there is a significant likelihood of further amputations [16]. Mortality is high, with 44.1% dying within 5 years of a diabetic amputation [17].

As Bury noted, chronic illnesses often “creep-up” rather than “break-out” [18]. For most, the amputation comes as an unwelcome surprise that suddenly announces a deterioration of a chronic illness. Patients who, for the most part, have lived with diabetes for several years are abruptly made aware of the seriousness of their medical condition. Unsurprisingly, as patients’ continued existence hinges upon the highly unpredictable trajectory of the amputation wound, the impact of the amputation can be profound. Self-image is affected, social roles destabilized and livelihoods endangered, potentially leading into a spiral of apathy, depression and lack of self-care [19,20,21,22]. Despite this, patients with minor DLEA are routinely discharged from hospital within a week for follow up in primary care, with the implicit expectation that life will carry on as usual [23].

Some existing work does investigate the impact of amputations [24,25,26,27] and of diabetic amputation in particular [e.g. 28–30]; however, fewer studies have taken an in-depth look at its destabilizing impact on patients’ lives as a whole. Additionally, whereas most studies are concerned with major amputations, minor amputations—involving the loss of a toe or part of a foot—are more common in the community dwelling population [31], and the impact of such operations should not be underestimated [32]. The present article elicits the experiences of community-dwelling patients, where diabetic toe and partial-foot amputations are far more common than below-knee (transtibial) or above-knee (transfemoral) ones.

The inherent uncertainty of the diabetic amputation wound healing trajectory represents a striking example of precariousness in patients. Post-amputation, a patient is “able to know nothing about one’s own future and therefore is hung by the present” [33]. Patients with recent diabetic amputations are “hung by the present”, grappling with a new reality of limb loss and reduced mobility, and unable to foresee or plan their future because everything hinges upon the wound recovering properly, which is only partially within their control.

3 Theoretical framework: precariousness and precarity

3.1 Conceptual clarification: precariousness vs precarity

A short terminological note is needed to clarify the meanings of terms used. Judith Butler’s use of ‘precariousness’ originally carried existential overtones that highlighted the radical contingency of the human condition. All life is precarious, because it is ontologically contingent (i.e., no life is secure from potential annihilation), whereas precarity is a “politically induced condition in which certain populations suffer from failing social and economic networks of support and become differentially exposed to injury, violence, and death” [34]. The precariat are the marginalized poor, disenfranchised and exposed to economic insecurity, injury, violence, and forced migration [35].

Over time the socio-political aspect has dominated research with a focus on how societal structures and forces impinge upon, support or threaten the continued existence of the individual. As both terms refer to someone in a state of insecurity or existential uncertainty, “precariousness” is often conflated with “precarity” and frequently discussed primarily within the frame of the human being-within-society. Many studies use “precariousness” interchangeably with “precarity” [e.g. 36–40]. However, conflating the two terms melds the socio-political causes of precariousness with the existential lived experience, resulting in conceptual blurring. Millar argues for maintaining a clear distinction between precarity and its related concepts, such as precariousness, to ensure that neither term loses its specificity and power as an analytical concept [41]. Indeed, using the terms interchangeably in academic discourse results in the more subjective, experiential and existential dimensions of precariousness being obscured by a focus on social and resource inequalities. While the latter are profoundly important, it is equally crucial that the ontological aspect of precariousness is not overlooked.

Our analysis draws from Butler’s original sense of existential contingency, and the experience of it. Following the Merriam-Webster dictionary, we define precariousness broadly as “dependent on chance circumstances, unknown conditions, or uncertain developments; characterized by a lack of security or stability that threatens with danger; […] depending on the will or pleasure of another” [42]. We have chosen to use “precariousness” throughout the paper, while using “precarity” to refer to financial precariousness arising from socioculturally constructed unevenness of distribution of resources.

4 Methods

Drawing from a study on the lived experiences of patients with recent diabetic amputation described in Zhu et al. [13], the authors conducted a secondary qualitative analysis to better understand patients’ experience of precariousness in the period following a diabetic amputation.

The initial study employed interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) to understand the unique, irreducible cultural and subjective lived experience of each individual in the first 12 months post-amputation. Using semi-structured in-depth individual interviews, IPA elicits the subjective lived experience of each interviewee, and takes into account contrasting experiences and nuances before cautiously extrapolating beyond individual cases to synthesize and extract meanings that transcend individual experience [43, 44].

Nine individuals who had undergone a diabetes-related lower extremity amputation in the past 12 months were interviewed between September 2018 and January 2019 about their post-amputation experiences (Table 1). Questions were kept deliberately open-ended, and centered around the physical and emotional impacts of the diabetic amputation and the post-amputation wound, patients’ coping strategies and social support. Interviewees were purposively sampled from among six polyclinics to provide a sample loosely representative of the larger diabetic amputee population in terms of sex, ethnicity and age. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Anonymized transcripts are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author and subject to institutional approval. The study was approved by the Domain-Specific Review Board of the National Healthcare Group (Ref No. 2018/00424).

Transcripts were re-read multiple times and annotated extensively, distilled into concise phrases and then synthesized into emergent themes across cases. Findings were reported in Zhu et al. [13]. For the secondary analysis, a more focused, iterative re-reading and analysis were done for each transcript, guided broadly by Braun and Clarke’s reflective thematic analysis approach [45] while using the lens of precariousness and precarity as a framework.

The study was conducted in Singapore, whose population of 5.9 million comprises ethnic Chinese, Malay, Indian, Eurasian and other ethnicities. While public healthcare is heavily government-subsidized, co-payment is an integral part of the public healthcare system. The public healthcare system takes care of the bulk of chronic illness management, including amputations resulting from diabetes. All diabetic amputations in this study were carried out in public healthcare facilities.

5 Results

Reflecting on the central concept of precariousness while analysing the transcripts revealed four aspects: emotional-existential precariousness, agentic precariousness, precariousness of one’s social identity and financial precarity.

5.1 Emotional-existential precariousness: uncertainty, hope and despair

The permanent physical loss caused by an amputation forces patients to confront their own mortality. Most interviewees were rudely shocked to discover they needed an amputation. Ayesha, for instance, a 37 year old baker, was on a family holiday when a fever erupted. She was bewildered and confused when informed that her toe was badly infected and “[we] have to cut off your toe”. Everything happened so quickly that she remained shaken by the experience. Amirul, a 62 year old grandfather, agreed to the amputation but said that the reality of it did not really sink in until later.

They told me they want to putt [cut] off, [number] two, three and four…. I just thought just ‘ah ok, never mind’. So [after the operation] I start [to count]—oh my God … That means my two feet there is gone. … I asked my grandson, (sniffs) ‘Eh—in human body, how many bones they have?’ Uh, 206. Ok. So now your grandfather have 196 only. (deep breath and laughs sadly). Wow. (Amirul)

For some interviewees, this sense of becoming destabilized continued after the operation, when they felt their lives had become “different”. After the amputation Ayesha describes feeling restless and confused:

Around 7 pm you feel, like … like so sad, like—I don’t know where to go. If go home also I think I’ll feel the same way. If I go... ah my father’s place also it’s like that. Because I’m .... before this I’m very active, like you know, we go out together, we play bowling... but—when this thing happened, I have to stop a lot of things. (Ayesha, 37 years old)

While disorientation, guilt, irascibility, grief, and fear of the future were commonly expressed sentiments among interviewees in the post-amputation period [13], a sense of uncertainty pervaded the other emotions and indeed seemed to be a salient feature that underlay the other emotions. Often, frustration arose from not knowing when and if they could ever resume ordinary life. Many interviewees talked about the difficulty of “waiting for the wound to heal”, along with fears about the consequences of the wound not healing.

Wound healing and its unpredictable trajectory were a central concern in the thoughts of all interviewees. The goal of complete healing represented a return to normality [13], whereas complications would delay a return to normal life. At the same time, interviewees were painfully aware that they had limited control over the wound healing outcome, given the propensity of diabetic wounds to dehiscence or failure. They knew there was no guarantee of the wound ever healing, and that the current amputation might only be the beginning of a series of further amputations and even death. As Amirul expressed it, “this diabetes, if you never [sic] take care, one year once ah, bop, bop, bop, bop [simulates chopping off action].” Teck had already lost four toes:

… First one I cut two. Then the second time I cut one more ... Then the last one is the fifth one. Finish already then… got infection. Then cut again, then cut again. … Tsk—scared they cut higher and higher. (Teck)

Patients were thus in constant tension between desperately hoping for a return to normal life, and fearing an unfavorable turn of events.

Complete wound healing and a return to “normal life” (i.e. pre-amputation life) was the goal of every interviewee: “I just want to get well faster. Once the wound is closed, I want to be like before.” (Ayesha) Amirul, who longed to resume his duties as a travelling religious teacher, expressed his hopes as a plea to God: “I also don’t know… please. This one, I hope, please.”

Yet even a healed amputation wound would always be dogged by the possibility of foot ulcer recurrence, and further amputation. In all the interviews, the threat of more extensive amputations, and even death, was never far from interviewees’ minds. Ayesha responded to a question about the distant future:

I really don’t know… [in five to ten years I’ll be] like this, or worse. If I never [sic] control, … [they may cut off] until here [gestures to lower leg], until here [gestures to upper leg]… I dare [not think]—I don’t know. Ya. [nervous laugh] (Ayesha)

Mei, a divorced homemaker aged 70, found herself ruminating constantly:

They say diabetics, sometimes they die from it. So I’m very scared that I will die very soon. I don’t know if I will? Sometimes … watching TV I start thinking at the same time– maybe I will die. The whole day thinking like that. (Mei)

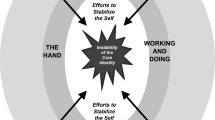

Other interviewees such as John (a 62 year old private hire driver) and Teck (a 61 year old supermarket packer) expressed similar sentiments. There was an observable to-and-fro as patients alternated often between sentiments of hope and fear. Many interviewees seemed to experience an “emotional see-saw”, with hope or fear gaining the upper hand at different points in the conversation. A mental and emotional tug-of-war arises from the dialectical tension between patients’ lived situation of precariousness and their active efforts to manage that precariousness. This is undergirded by pervasive uncertainty around the outcome of wound healing, as shown in Fig. 1:

This was clearly expressed by Isaac, a father of two, who vacillated between worrying about providing for his family and maintaining an optimistic outlook:

How am I going to work? …it’s all very depressing. I’ve to think of this, but the moment I think of negative things, it really pulls me down, so I have to—not to think of this, I have to … put this at the back burner. […] At the back of my head. Put at the back burner and burn it, you see? […] (Pause). I have to think that. I have to look forward. (Isaac, 54 years old)

A similar dynamic can be seen in the striking contrast between Ayesha’s hopeful future plans that included cooking, bowling and working, and her fears of not being able to realize her plans. Like Isaac, she talked herself into positivity while battling the tendency to sink into despondency:

You have to surround yourself with all those positive things…you cannot be […] sitting down talking, like, ‘Oh, my toe… oh my toe… Why is this happening to me?’ […] You have to fight. You have to go. You have to work! (Ayesha)

Serious comorbidities such as kidney disease made the prospect of mortality even more probable. Interviewees such as John and Teck, both of whom also had kidney disease, felt overwhelmed by the slim odds of recovery, tilting the balance between hope and fear toward despair.

I have to … wait for the wound to heal. And ... hopefully it heals. But if there is further… complications, and if the wound doesn’t heal, the leg may have to go. That is the worrying part. (Pause) They said the feet may have to go… There—there’s nothing for certain at this moment. (John)

[I’m] scared they cut higher and higher… on the leg up. That one only I scared… I tell my sister, if really happen, then…. Everything I don’t take care already… Everything I give [up]… I don’t want to stay already. (Teck)

5.2 Agentic precariousness: autonomy threatened by immobility

Besides emotional and existential precariousness, interviewees were also rendered precarious in their personal agency. As independent adults, our interviewees were accustomed to moving about freely. In the post-amputation period, however, while the wound was still recovering, patients found their self-agency and mobility drastically reduced. Assistance was often required for daily activities such as showering, so as not to risk the wound healing process. Moreover, their ability to go wherever they wished was curtailed by fear of aggravating the wound, and sometimes by family members’ prohibitions. This often led them to feel both guilty and resentful for needing help. Isaac, who used help run transport operations, now needed to depend on others even to use the bathroom, which frustrated him and led to temperamental behaviour, for which he later felt remorse and guilt. Similarly, John, who was used to driving others around, described feeling frustration, helplessness and ennui at the enforced passivity:

Because my movements are limited, there’s nothing much to do, except—to pass the day reading some materials... and—resting. There’ s nothing—there’ s nothing more that I can ... do. … My movements are limited … I’ve to try to find ways, uh, to while away the time. (John)

After the amputation, Ayesha found herself constantly teary, and explained that

I wasn’t grieving for my toe…I was grieving because—I’m crying because … I need a lot of help from others….[My] movements have to be restricted. I need help—people to help me, I cannot stand too long, I cannot sit too long, I cannot put my leg down… because …. the nurses worry that the wound will become wet, and then, you know, it will take longer time to heal. (sniffs) So I really need help. I’m lucky that I got this friend to help me all the while, (voice quavers, starts to cry) to help me shower, all this. (silent weeping) (Ayesha).

The physical loss of independence, together with prohibitions and fears about the wound, were often internalized and led to self-imposed restrictions, such that patients limited their own agency. For some patients, the threat of wound complications led to them doing everything possible to avoid affecting wound recovery. This included limiting the range of actions they considered possible for them to engage in. For example, some recovering amputees were afraid to walk normally, for fear of causing damage to the healing wound: “The physio asked me to walk as per normal, but I’m scared to step on the ground, with the wound there…” (Ayesha) Preoccupation with the fear of accidental injury was echoed by Alan, Ayesha, Mei and John, who told us, “Now that my amputation is on, I do not go out”. Alan explained, “They told me, ‘If… the skin tears, then it’s going to be a major problem. The skin will not join again.’”.

Concerned about the potentially dire consequences of endangering the wound by putting pressure on it, most interviewees chose to remain home rather than risk injuring themselves by going out or even standing up. These internalized fears led to self-limiting behaviours such as staying home and trying not to move too much, compounding a sense of loss of personal agency which also often led to frustration. One consequence of this self- and other-enforced restraint was a certain restlessness or ennui, sometimes resulting in insomnia. As John complained, “When you rest the whole day… at night you can’t sleep.” Moreover, for some interviewees, physical self-confinement led to social isolation and changes to social identity, resulting in social precariousness.

Other times, the restrictions on freedom were other-imposed. For instance, when Ayesha moved in with her parents in the post-amputation period, she was restricted from going into the kitchen. Even lightly skipping down a step brought on a scolding for not being careful of her injury: “Somebody start to shout already, like, ‘What are you doing?’” These prohibitions reinforced the mental restrictions discussed earlier, making interviewees feel even less able to exercise their individual autonomy.

In short, distress at having to rely on others and the inability to act independently during the post-amputation period impinged upon the sense of agency of the interviewees. Interviewees were constantly faced with things that they could not objectively do without harming the wound, leading to a sense of constraint; moreover, the subjective fear of jeopardizing the wound healing further caused interviewees to refrain from fully exercising their personal agency—for instance, in walking around—even when this was permissible. Additionally, out of concern, their families and relatives tended to prohibit them from doing things. Consequently, patients’ previously taken-for-granted sense of personal autonomy and agency were sorely tested during the recuperation process, frequently leading to frustration mingled with a strong desire to reclaim their independence.

5.3 Social precariousness: changed social roles and identity

A third source of precariousness was a loss of social roles. According to symbolic interactionists Carter and Fuller, social roles arise from a “reciprocal influence of networks or patterns of relationships in interactions as they are shaped by various levels of social structures.” [46] Stryker adds that every social role contains “expectations which are attached to [social] positions” and are “symbolic categories [that] serve to cue behaviour” [47]. Amputation and loss of mobility, along with the unpredictability of a good outcome, meant that interviewees had to adapt to the loss of their former roles as breadwinners or homemakers—a loss that might be temporary or permanent. Moreover, they were often treated by others as an invalid. Previous social roles and identities were redefined overnight, leaving patients adrift in their loss of social identity.

Parental roles were sometimes reversed, as anxious adult children took on the role of concerned authority figures and unwittingly treated their parents like children, scolding them and restricting their physical activity: Sarai’s daughter refused to let her mother go out unaccompanied, and prohibited her from getting up from the wheelchair in case she fell down. Likewise, Isaac, who had had amputations on both legs, was admonished for falling off the bed:

… I was shouting for [my son]. He said, “What happened? What did you do?” “Oh, no no, I just slipped and fell…” [mimicking his son scolding] “How come you fell?” (Isaac)

“They don’t let me” was a common complaint that illustrated the role changes (Amirul, Isaac, Ayesha), as caregivers would curtail interviewees’ movements, diet, and activities. The loss of agency was keenly felt as disempowering, and tended to position interviewees as helpless beings who could not do many things. The loss of status in family and social relationships contributed to a sense of social precariousness as interviewees attempted to reclaim a sense of their social selves, within the family or outside. This is also linked to professional identities, discussed in the following section.

Finally, amputation-related social stigma [13] also affected interviewees’ social identities. While some individuals experienced only mild embarrassment or purported not to be affected (John, Lee), others felt so ostracized or embarrassed about their diabetic footwear or missing limb that they withdrew from social interaction (e.g. Amirul, Isaac, Ayesha).

At times, critical comments from those in interviewees’ social circles made them even more aware of the precariousness of their situation. Ayesha recounted that “this auntie said, ‘Wah, you cut one toe. My cousin, cut until three times. The next time he passed away.’” The incident left her outraged by the insensitivity of others and their “stupid questions”:

I was like (sputtering)—Huh? … [I] don’t need that kind of comment. … Those people around you, they don’t know the real thing, they go and [criticise] pum- pum- pum- pum like that... And then sometimes you feel like you want to argue [but there’s] no point explaining things to people who don’t understand. (Ayesha)

Feeling judged negatively, she withdrew socially to avoid “those mouths”, and at the point of the interview she had been declining social invitations for several weeks.

Among the interviewees, Isaac suffered the most visible impact from his latest amputation. Left with only his upper leg on one side and half a foot on the other, he had stumps on both legs and used a wheelchair. He found himself “othered” and distanced from the world of able-bodied people to which he had previously belonged:

When I was working in [public transport company], there were people who are wheelchair-bound—have no leg, or on a walking frame…so... we assist them, so—yes, I’m used to seeing them... used to assisting them, used to talking to them, [but] I—I didn’t realize that I will be in their situation. (Isaac)

Like Ayesha, this discomfort resulted in self-imposed isolation to avoid the public gaze, although he greatly missed interaction with larger society and would look forward to his medical appointments as reasons to leave the house and “visit the world”. He did not feel comfortable being alone in public, as he felt stared at “like an alien” with his visible stump.

The only interviewee who lived alone, Teck, had a slightly different experience. His amputation underscored his familial role as the youngest sibling. His sisters were deeply concerned and wanted to take care of him, while he both needed and rejected their care. He felt intense guilt over his older sisters, who were elderly had their own families, coming over to help him cook and clean. So deeply did it perturb him that he did not even tell them he had gone for the amputation, and described the feeling of being a burden to them as “worse” than the pain of the amputation.

With the loss of previous social identities as a consequence of the amputation, and often feeling alienated from normalcy and social life, interviewees needed the help of close others to reintegrate into society and/or to reaffirm them in their roles. Thus, Isaac was consoled by his children reminding him that despite his multiple amputations and being unable to walk, “You’re still the same father.” Ayesha eventually considered coming out of her isolation when her husband was due for a bowling competition, in order to support him. For John, who felt “useless” as his wife now had to be the sole breadwinner, it was a band of former schoolmates who formed his de facto support group and would take him out to lunch, thereby reminding him that he was still known and valued beyond his illness. Despite the affirmations of close relatives and friends, however, the work of reshaping and re-negotiating their social identities, learning to fit into new roles or let go of old ones, had to be done individually, and this could be a lonely task.

5.4 Financial precarity and professional identity precariousness

Despite public subsidies, two-thirds of the interviewees found themselves in a financially precarious situation because of high and unremitting medical costs. The uncertain wound healing trajectory contributed to job insecurity, which in turn made access to financial resources precarious. Even those without pressing financial concerns found their professional identities rendered precarious, which could negatively affect their self-esteem, compounding the physical, emotional and social impact of the disease.

All interviewees agreed the financial cost of the amputation was high; about half (Amirul, John, Isaac, Ayesha) worried about finances. Even those with stable finances grappled with uncertainty about the future trajectory of the diabetic foot, and it was the unforeseeable costs of future treatment that worried them most. The direct and indirect costs of diabetes—repeated medical appointments for wound dressing and treatment, the rental of wound care machines, the costs of medicines, glucose test kits, wheelchairs and mobility devices—weighed most upon interviewees who had previously been breadwinners (John, Isaac):

Of course, it’s a financial strain upon—(pause) […] Because there is only one channel of income—that is, my wife. (pause) My son is in university and... uh... Tsk. And ... me having this disease, and—you know, financially—we are spending money more than earning money. (John)

The loss of work-related identities also profoundly affected amputees. While six of the nine interviewees had been working outside the home before their amputations, at the time of interview, only two had actually returned to work. Several interviewees had jobs that required a lot of standing, walking, travelling or driving (Amirul, John, Isaac, Teck, Ayesha). These interviewees found their sense of professional identity eroded, as the fragility of the physical wound threatened the self-identity associated with professional work.

John had been a successful businessman before his business failed; he had then started a second career as a driver. Now the amputation and his other conditions endangered this means of livelihood too. His post-amputation trajectory is marked by a strong sense of existential uselessness and hopelessness:

[Referring to himself] You find yourself …. quite useless. Your abilities are limited, now—especially to earning money, especially to … you know, to—to work, and to make yourself useful. So… while I was driving […] even though the income was very low, but then, it was a little bit of a satisfaction that you’re performing a service. (John)

The inability to work is linked to not only income but self-image. Just as social self-identity is constructed in relation to one’s family and social setting, one’s professional self-identity is constructed by one’s position in the workplace. Being unable to work because of the amputation made John feel he had lost both his social role as family breadwinner and his work-related identity as someone who could be “useful”.

Isaac, too, was worried about losing his job of over 30 years because of his limited mobility. His role in transport operations had required a lot of moving about. Despite an excellent past career, he considered the likelihood of keeping his job tenuous at best. He felt sad that his previous work achievements might now “count for nothing” as he could no longer perform as before. He asked repeatedly, “What am I going to do, how am I going to survive, how am I going to work?” Although he had requested a transfer to a desk-bound position, he was acutely aware of the precariousness of his situation, which was dependent on the decisions of his superiors at work.

Although did not need the income, Teck, a supermarket packer, especially feared losing his job, which provided a buffer against the reality of his multiple diseases, because he tended to “think too much” about when he was alone. His work afforded him a much-needed distraction and a form of social life, and he worried that wound complications could deprive him even of this:

[If they] just cut on top, cannot work already… cut like this only [gestures to upper leg], cannot work already. Then.. not to work I stay at home and I do what? […] I cannot s-stand [it] ah, I have to work ah. Because, [if] you—every day stay at home…. Worse ah. […] Now working, at least got people talk to you, [it’s] easier [to bear]. (Teck)

6 Discussion

Diabetic amputees are a prime example of precariousness in multiple respects: their very existence is a precarious one, as they face daily the uncertainty of continued existence. The outcome of wound healing, which is a factor mostly outside their control, determines in large part what the future will be. They are physically precarious, because the wound is vulnerable; this leads to agentic precariousness given their limited physical agency, also dependent on the status of the wound. Social precariousness arises from their social identities, when they are no longer able to play the roles they used to. Finally, their situation places them in a position of financial precarity because of the uncertain trajectory of the illness and its accompanying financial strain, coupled with their reduced ability to work. At the root of all this precariousness is the unpredictability of wound healing, the future trajectory of the disease, and the threat of mortality.

Our analysis, by teasing out the various facets of precariousness, made it clear that while distinct, the different aspects fed into one another. Specifically, the physically precarious state of the wound led to emotional-existential precariousness and agentic precariousness in the patient—patients were on one hand abruptly confronted with their mortality; on the other hand, they felt inhibited both physically and mentally because of fear of injuring the wound. Agentic precariousness, in turn, was deeply linked with the amputee’s social relationships. Concerned family members provided a stabilizing force against existential-emotional and social precariousness, by reminding patients that they were important to them and reaffirming them in their pre-amputation social roles. Yet, overly protective relatives who hemmed in amputees’ personal autonomy with prohibitions about moving about instead unwittingly contributed to agentic precariousness: by preventing them from acting as independent adults, they contributed to patients’ sense of loss of personal agency. Social withdrawal was not uncommon—although for interviewees like Teck, who already lived alone and had life threatening comorbidities, the reality of his existentially precarious situation proved too much to bear alone, leading him toward despair. Realizing how much he needed to be with other people for company, he was impelled to continue to work at his job as a packer, even at the risk of wound complications. Ironically, therefore, the strategy Teck used to manage his anxieties about his existential precariousness increased his physical precariousness, but helped him cope better with the realities of his precarious existence.

Teck had few financial concerns, and work was for him a way to mitigate his existential worries and emotional precariousness. For other interviewees, professional identity was linked to personal and social identity, particularly in family roles such as father/breadwinner. One’s inability to work and provide for the family, compounded with the uncertainty of being able to do so in future, led to feelings of existential uselessness and seeing oneself as a failure. Such interviewees’ work identities, livelihoods and even personal identities were at risk, endangered by job insecurity which hinged around the unpredictability of the wound healing. Isaac’s refrain—“How am I going to survive? How am I going to work?”—shows how financial precarity ties back into existential concerns for survival. Being out of employment meant not just a loss of professional and social identity, but also raised the question of financial survival given the costs of diabetic treatments and complications.

Our study contributes to the discussion on precariousness and precarity by re-establishing the distinction between them. Exploring the various ways amputees’ lives are made precarious teases out the different aspects of precariousness. Butler’s concept of precariousness, mentioned earlier, has both social and existential elements: it implies the inescapable interdependence of “living socially… the fact that one’s life is always in some sense in the hands of the other.” [34, p. 14] In our interviews, the social intersected with the existential in many ways, including in the reconstruction of one’s self-identity following the crisis of a diabetic amputation. The reality that interviewees’ lives are “in the hands of the other” is especially seen in the uncertainty Isaac faces about the security of his job, post-amputation. It is his superiors and the wound status which will decide his future. For Ayesha, her dreams of returning to baking depended on the wound healing. Despite an almost feverish zeal to ensure the wound did heal by doing everything possible to keep it from being wet, she was forced to acknowledge that the outcome was by no means certain.

Our findings cohere with the model of cumulative complexity proposed by Shippee et al. [19], which predicts that when the burden of illness exceeds the capacity to cope and resources available, patients fall into disequilibrium and may be tempted to give up on self-care. Interviewees who appeared the most distressed (e.g. Teck, John, Isaac), related a chain of cumulative misfortunes, in which health conditions, social conditions, and financial concerns combined to increase their sense of precariousness to a point where they were sometimes tempted to despair. While family and social support buffered the impact to some extent, it was also evident that the lived experience of amputation includes an element of loneliness and intimate loss which even loved ones could not fully share.

This study was conducted within a predominately Asian population with a mix of Chinese, Malay and Indian ethnicities. Given the relatively collective focus of these societies, in which individual identity is deeply bound with social roles and identities, it is possible that social and identity precariousness might be heightened compared to other societies that score higher on individualism [48]. On the other hand, in a society with a strong work ethic such as Singapore where a strong cultural importance is placed upon work and being useful, being unable to work might exacerbate the impact of feeling useless and loss of personal identity, as seemed to be the case for John, Isaac and Teck. Further work should look into these dimensions, especially considering the impact of even a minor diabetic amputation and its repercussions on the patient, personally and socially.

While our study uncovered the experience of precariousness as common to most or all of our interviewees, the impact of a DLEA varies widely, depending on individual circumstances and personalities. Within our sample, some patients were more evidently anxious about their uncertain future than others, who maintained a stoic attitude. Given the richness of data produced, further exploration of the experiences of gender and ethnic subgroups would be a valuable next step for research on this topic.

7 Conclusion

In discussing the lived experiences of diabetic lower limb amputees in primary care, a relatively under-researched population, we have drawn attention to precariousness in its various dimensions. Healthcare professionals treating patients with diabetic amputation should be aware of the psycho-emotional, social and professional consequences of even a minor amputation, which can severely disrupt a patient’s life-world. Awareness of the multiple dimensions of precariousness—emotional, existential, agentic, social and financial—can help them consider how best to support patients’ strategies to reassert agency through cognitive self-management and self-empowerment. Caregivers of patients should also be apprised of the psycho-emotional and social crises post-amputation patients may undergo, so as to be better able to understand and support them.

Data availability

To protect the confidentiality and privacy of patient interviewees, the full transcripts cannot be made publicly available, but the anonymized transcripts may be made available upon reasonable request, subject to institutional approval by the National Healthcare Group Polyclincs. Please contact the corresponding author for more information.

References

Grenier A, Lloyd L, Phillipson C. Precarity in late life: rethinking dementia as a ‘frailed’ old age. Sociol Health Illn. 2017;39(2):318–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12476.

Wilson JA, Yochim EC. Mothering through precarity: women’s work and digital media. Durham: Duke University Press; 2017.

Read UM, Nyame S. “It Is Left to Me and My God”: precarity, responsibility, and social change in family care for people with mental illness in Ghana. Africa Today. 2019;65(3):3–28. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.65.3.02.AfricaToday.

Grenier A, Phillipson C, Laliberte Rudman D, Hatzifilalithis S, Kobayashi K, Marier P. Precarity in late life: understanding new forms of risk and insecurity. J Aging Stud. 2017;43:9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2017.08.002.

McKee M, Reeves A, Clair A, Stuckler D. Living on the edge: precariousness and why it matters for health. Arch Public Health. 2017;75(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-017-0183-y.

Sirviö A, Ek E, Jokelainen J, Koiranen M, Järvikoski T, Taanila A. Precariousness and discontinuous work history in association with health. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(4):360–7.

Vives A, et al. Employment precariousness and poor mental health: evidence from Spain on a new social determinant of health. J Environ Public Health. 2013;2013:1–10.

Whittle HJ, et al. Precarity and health: theorizing the intersection of multiple material-need insecurities, stigma, and illness among women in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2020;245:112683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112683.

Tentolouris N, Al-Sabbagh S, Walker MG, Boulton AJM, Jude EB. Mortality in diabetic and nondiabetic patients after amputations performed from 1990 to 1995: a 5-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(7):1598–604. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.7.1598.

Lin X, et al. Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: an analysis from 1990 to 2025. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):14790. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71908-9.

Zhou B, et al. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4·4 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1513–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8.

Ang Y, Yap CW, Saxena N, Lin L-K, Heng BH. Diabetes-related lower extremity amputations in Singapore. Proc Singap Healthc. 2016;26(2):76–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/2010105816663521.

Zhu X, Goh LJ, Chew E, Lee M, Bartlam B, Dong L. Struggling for normality: experiences of patients with diabetic lower extremity amputations and post-amputation wounds in primary care. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2020;21: e63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S146342362000064X.

Horgan O, MacLachlan M. Psychosocial adjustment to lower-limb amputation: a review. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(14–15):837–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280410001708869.

Schofield CJ, et al. Mortality and hospitalization in patients after amputation: a comparison between patients with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(10):2252–6. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc06-0926.

Rathnayake A, Saboo A, Malabu UH, Falhammar H. Lower extremity amputations and long-term outcomes in diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review. World J Diabetes. 2020;11(9):391–9. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v11.i9.391.

Yammine K, Hayek F, Assi C. A meta-analysis of mortality after minor amputation among patients with diabetes and/or peripheral vascular disease. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(6):2197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.07.086.

Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn. 1982;4(2):167–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939.

Shippee ND, Shah ND, May CR, Mair FS, Montori VM. Cumulative complexity: a functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:11.

May C, Montori V, Mair F. We need minimally disruptive medicine. Br Med J. 2009;339:3.

Cascini S, et al. Survival and factors predicting mortality after major and minor lower-extremity amputations among patients with diabetes: a population-based study using health information systems. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(1): e001355. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001355.

Senra H, Oliveira RA, Leal I, Vieira C. Beyond the body image: a qualitative study on how adults experience lower limb amputation. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(2):180–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215511410731.

Ostler C, Ellis-Hill C, Donovan-Hall M. "Expectations of rehabilitation following lower limb amputation: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(14):1169–75. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.833311.

Heavey E. The multiple meanings of disability in interviews with lower limb amputees. Commun Med. 2013;10(2):129–39.

Heavey E. The body as biography. In: Schiff B, McKim AE, Patron S, editors. Life and narrative: the risks and responsibilities of storying experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 139.

Rybarczyk B, Edwards R, Behel J. Diversity in adjustment to a leg amputation: Case illustrations of common themes. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(14–15):944–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280410001708986.

Kulkarni J. Post amputation syndrome. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008;32(4):434–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/03093640802258637.

Hamill R, Carson S, Dorahy M. "Experiences of psychosocial adjustment within 18 months of amputation: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(9):729–40. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638280903295417.

MacKay C, et al. A qualitative study exploring individuals’ experiences living with dysvascular lower limb amputation. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;44:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1803999.

Crocker RM, Palmer KNB, Marrero DG, Tan T-W. Patient perspectives on the physical, psycho-social, and financial impacts of diabetic foot ulceration and amputation. J Diabetes Complicat. 2021;35(8):107960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2021.107960.

Riandini T, et al. National rates of lower extremity amputation in people with and without diabetes in a multi-ethnic Asian population: a ten year study in Singapore. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022;63(1):147–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.09.041.

Nazri M, Aminudin C, Ahmad F, Jazlan MM, Ab RJ, Ramli M. Quality of life of diabetes amputees following major and minor lower limb amputations. Med J Malaysia. 2019;74(1):25–9.

Berardi F, Empson E. Precarious rhapsody: semiocapitalism and the pathologies of the post-alpha generation. Minor Compositions. 2009.

Butler J. Frames of war: when is life grievable? London: Verso Books; 2010.

Kasmir S. Precarity. The Cambridge encyclopaedia of anthropology. 2018. https://www.anthroencyclopedia.com/entry/precarity. Accessed 8 Oct 2023.

McCormack D, Salmenniemi S. The biopolitics of precarity and the self. Eur J Cult Stud. 2016;19(1):3–15.

Vij R. The global subject of precarity. In: Vij R, Kazi T, Wynne-Hughes E, editors. Precarity and international relations. Berlin: Springer; 2021. p. 63–92.

Cruz-Del Rosario T, Rigg J. Living in an age of precarity in 21st Century Asia. J Contemp Asia. 2019;49(4):517–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2019.1581832.

Portacolone E. The notion of precariousness among older adults living alone in the U.S. J Aging Stud. 2013;27(2):166–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2013.01.001.

Portacolone E, Rubinstein RL, Covinsky KE, Halpern J, Johnson JK. The precarity of older adults living alone with cognitive impairment. Gerontologist. 2019;59(2):271–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx193.TheGerontologist.

Millar KM. Toward a critical politics of precarity. Sociol Compass. 2017;11(6): e12483.

Merriam-Webster I. Precarious. Merriam Webster Dictionary: Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, vol. 2022. 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/precarious. Accessed 1 Oct 2023.

Larkin M, Watts S, Clifton E. Giving voice and making sense in interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):102–20. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp062oa.

Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretive phenomenological analysis: theory, method and research. London: Sage; 2009.

Braun V, Clarke V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual Psychol. 2022;9(1):3.

Carter MJ, Fuller C. Symbolic interactionism. Sociopedia Isa. 2015;1(1):1–17.

Stryker S. Symbolic interactionism: a social structural version. Menlo Park: Benjamin Cummings; 1980.

Hofstede G. Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Read Psychol Cult. 2011;2(1):8.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants of this study, and the clinic staff of the polyclinics where the research was carried out for their support and assistance.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Centre for Primary Health Care Research and Innovation, a partnership between the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University Singapore and the National Healthcare Group Singapore [Grant Reference Number 002].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EALC: conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; validation; visualization; writing—original draft and editing. MCLL: conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; validation; visualization; writing and editing. BB: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing and editing. LJG: conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; resources; validation; writing—review and editing. LD: conceptualization; formal analysis; funding acquisition; methodology; resources; validation; writing—review and editing. XZ: conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; visualization; writing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics review board of the relevant organization (Ref No. 2018/00424).

Consent for publication

Potential participants were given an Information Sheet for their consideration prior to participation and were given ample time to decide whether to participate. Participation in the study was completely voluntary for all participants. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to data collection. All interview transcripts were anonymised, and pseudonyms are used throughout the manuscript to protect privacy and confidentiality.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chew, E.A.L., Lee, M.C.L., Bartlam, B. et al. Between hope and despair: experiences of precariousness and precarity in the lived experiences of recent diabetic amputees in primary care. Discov Soc Sci Health 4, 5 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-024-00062-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-024-00062-8